148 KiB

第三章:数据模型与查询语言

语言的边界就是思想的边界。

—— 路德维奇・维特根斯坦,《逻辑哲学》(1922)

Data models are perhaps the most important part of developing software, because they have such a profound effect: not only on how the software is written, but also on how we think about the problem that we are solving.

Most applications are built by layering one data model on top of another. For each layer, the key question is: how is it represented in terms of the next-lower layer? For example:

- As an application developer, you look at the real world (in which there are people, organizations, goods, actions, money flows, sensors, etc.) and model it in terms of objects or data structures, and APIs that manipulate those data structures. Those structures are often specific to your application.

- When you want to store those data structures, you express them in terms of a general-purpose data model, such as JSON or XML documents, tables in a relational database, or vertices and edges in a graph. Those data models are the topic of this chapter.

- The engineers who built your database software decided on a way of representing that JSON/relational/graph data in terms of bytes in memory, on disk, or on a network. The representation may allow the data to be queried, searched, manipulated, and processed in various ways. We will discuss these storage engine designs in [Link to Come].

- On yet lower levels, hardware engineers have figured out how to represent bytes in terms of electrical currents, pulses of light, magnetic fields, and more.

In a complex application there may be more intermediary levels, such as APIs built upon APIs, but the basic idea is still the same: each layer hides the complexity of the layers below it by providing a clean data model. These abstractions allow different groups of people—for example, the engineers at the database vendor and the application developers using their database—to work together effectively.

Several different data models are widely used in practice, often for different purposes. Some types of data and some queries are easy to express in one model, and awkward in another. In this chapter we will explore those trade-offs by comparing the relational model, the document model, graph-based data models, event sourcing, and dataframes. We will also briefly look at query languages that allow you to work with these models. This comparison will help you decide when to use which model.

术语:声明式查询语言

Many of the query languages in this chapter (such as SQL, Cypher, SPARQL, or Datalog) are declarative, which means that you specify the pattern of the data you want—what conditions the results must meet, and how you want the data to be transformed (e.g., sorted, grouped, and aggregated)—but not how to achieve that goal. The database system’s query optimizer can decide which indexes and which join algorithms to use, and in which order to execute various parts of the query.

In contrast, with most programming languages you would have to write an algorithm—i.e., telling the computer which operations to perform in which order. A declarative query language is attractive because it is typically more concise and easier to write than an explicit algorithm. But more importantly, it also hides implementation details of the query engine, which makes it possible for the database system to introduce performance improvements without requiring any changes to queries. [1].

For example, a database might be able to execute a declarative query in parallel across multiple CPU cores and machines, without you having to worry about how to implement that parallelism [2]. In a hand-coded algorithm it would be a lot of work to implement such parallel execution yourself.

关系模型与文档模型

The best-known data model today is probably that of SQL, based on the relational model proposed by Edgar Codd in 1970 [3]: data is organized into relations (called tables in SQL), where each relation is an unordered collection of tuples (rows in SQL).

The relational model was originally a theoretical proposal, and many people at the time doubted whether it could be implemented efficiently. However, by the mid-1980s, relational database management systems (RDBMS) and SQL had become the tools of choice for most people who needed to store and query data with some kind of regular structure. Many data management use cases are still dominated by relational data decades later—for example, business analytics (see “Stars and Snowflakes: Schemas for Analytics”).

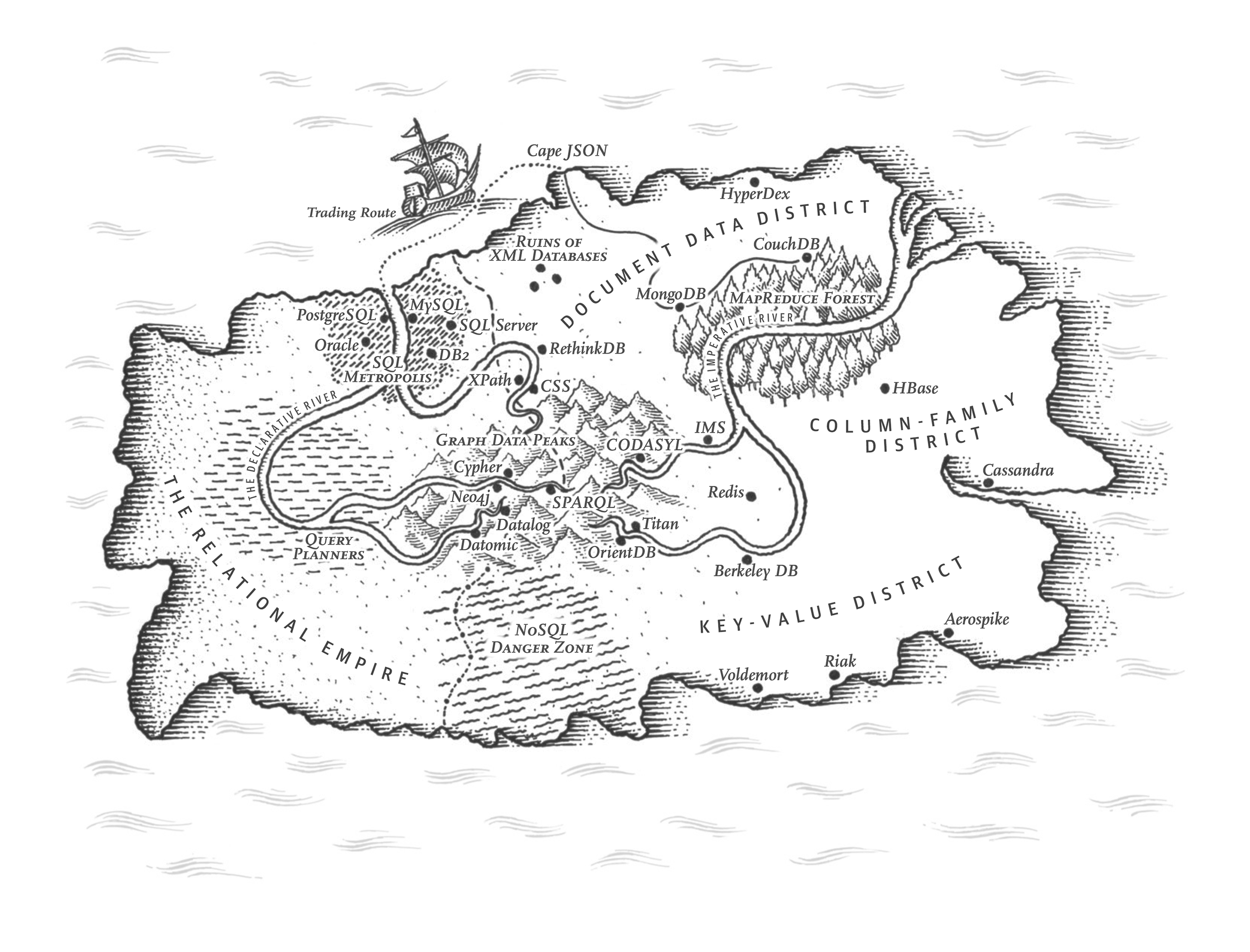

Over the years, there have been many competing approaches to data storage and querying. In the 1970s and early 1980s, the network model and the hierarchical model were the main alternatives, but the relational model came to dominate them. Object databases came and went again in the late 1980s and early 1990s. XML databases appeared in the early 2000s, but have only seen niche adoption. Each competitor to the relational model generated a lot of hype in its time, but it never lasted [4]. Instead, SQL has grown to incorporate other data types besides its relational core—for example, adding support for XML, JSON, and graph data [5].

In the 2010s, NoSQL was the latest buzzword that tried to overthrow the dominance of relational databases. NoSQL refers not to a single technology, but a loose set of ideas around new data models, schema flexibility, scalability, and a move towards open source licensing models. Some databases branded themselves as NewSQL, as they aim to provide the scalability of NoSQL systems along with the data model and transactional guarantees of traditional relational databases. The NoSQL and NewSQL ideas have been very influential in the design of data systems, but as the principles have become widely adopted, use of those terms has faded.

One lasting effect of the NoSQL movement is the popularity of the document model, which usually represents data as JSON. This model was originally popularized by specialized document databases such as MongoDB and Couchbase, although most relational databases have now also added JSON support. Compared to relational tables, which are often seen as having a rigid and inflexible schema, JSON documents are thought to be more flexible.

The pros and cons of document and relational data have been debated extensively; let’s examine some of the key points of that debate.

对象关系不匹配

Much application development today is done in object-oriented programming languages, which leads to a common criticism of the SQL data model: if data is stored in relational tables, an awkward translation layer is required between the objects in the application code and the database model of tables, rows, and columns. The disconnect between the models is sometimes called an impedance mismatch.

注意

The term impedance mismatch is borrowed from electronics. Every electric circuit has a certain impedance (resistance to alternating current) on its inputs and outputs. When you connect one circuit’s output to another one’s input, the power transfer across the connection is maximized if the output and input impedances of the two circuits match. An impedance mismatch can lead to signal reflections and other troubles.

对象关系映射(ORM)

Object-relational mapping (ORM) frameworks like ActiveRecord and Hibernate reduce the amount of boilerplate code required for this translation layer, but they are often criticized [6]. Some commonly cited problems are:

- ORMs are complex and can’t completely hide the differences between the two models, so developers still end up having to think about both the relational and the object representations of the data.

- ORMs are generally only used for OLTP app development (see “Characterizing Analytical and Operational Systems”); data engineers making the data available for analytics purposes still need to work with the underlying relational representation, so the design of the relational schema still matters when using an ORM.

- Many ORMs work only with relational OLTP databases. Organizations with diverse data systems such as search engines, graph databases, and NoSQL systems might find ORM support lacking.

- Some ORMs generate relational schemas automatically, but these might be awkward for the users who are accessing the relational data directly, and they might be inefficient on the underlying database. Customizing the ORM’s schema and query generation can be complex and negate the benefit of using the ORM in the first place.

- ORMs often come with schema migration tools that update database schemas as model definitions change. Such tools are handy, but should be used with caution. Migrations on large or high-traffic tables can lock the entire table for an extended amount of time, resulting in downtime. Many operations teams prefer to run schema migrations manually, incrementally, during off peak hours, or with specialized tools. Safe schema migrations are discussed further in “Schema flexibility in the document model”.

- ORMs make it easy to accidentally write inefficient queries, such as the N+1 query problem [7]. For example, say you want to display a list of user comments on a page, so you perform one query that returns N comments, each containing the ID of its author. To show the name of the comment author you need to look up the ID in the users table. In hand-written SQL you would probably perform this join in the query and return the author name along with each comment, but with an ORM you might end up making a separate query on the users table for each of the N comments to look up its author, resulting in N+1 database queries in total, which is slower than performing the join in the database. To avoid this problem, you may need to tell the ORM to fetch the author information at the same time as fetching the comments.

Nevertheless, ORMs also have advantages:

- For data that is well suited to a relational model, some kind of translation between the persistent relational and the in-memory object representation is inevitable, and ORMs reduce the amount of boilerplate code required for this translation. Complicated queries may still need to be handled outside of the ORM, but the ORM can help with the simple and repetitive cases.

- Some ORMs help with caching the results of database queries, which can help reduce the load on the database.

- ORMs can also help with managing schema migrations and other administrative activities.

The document data model for one-to-many relationships

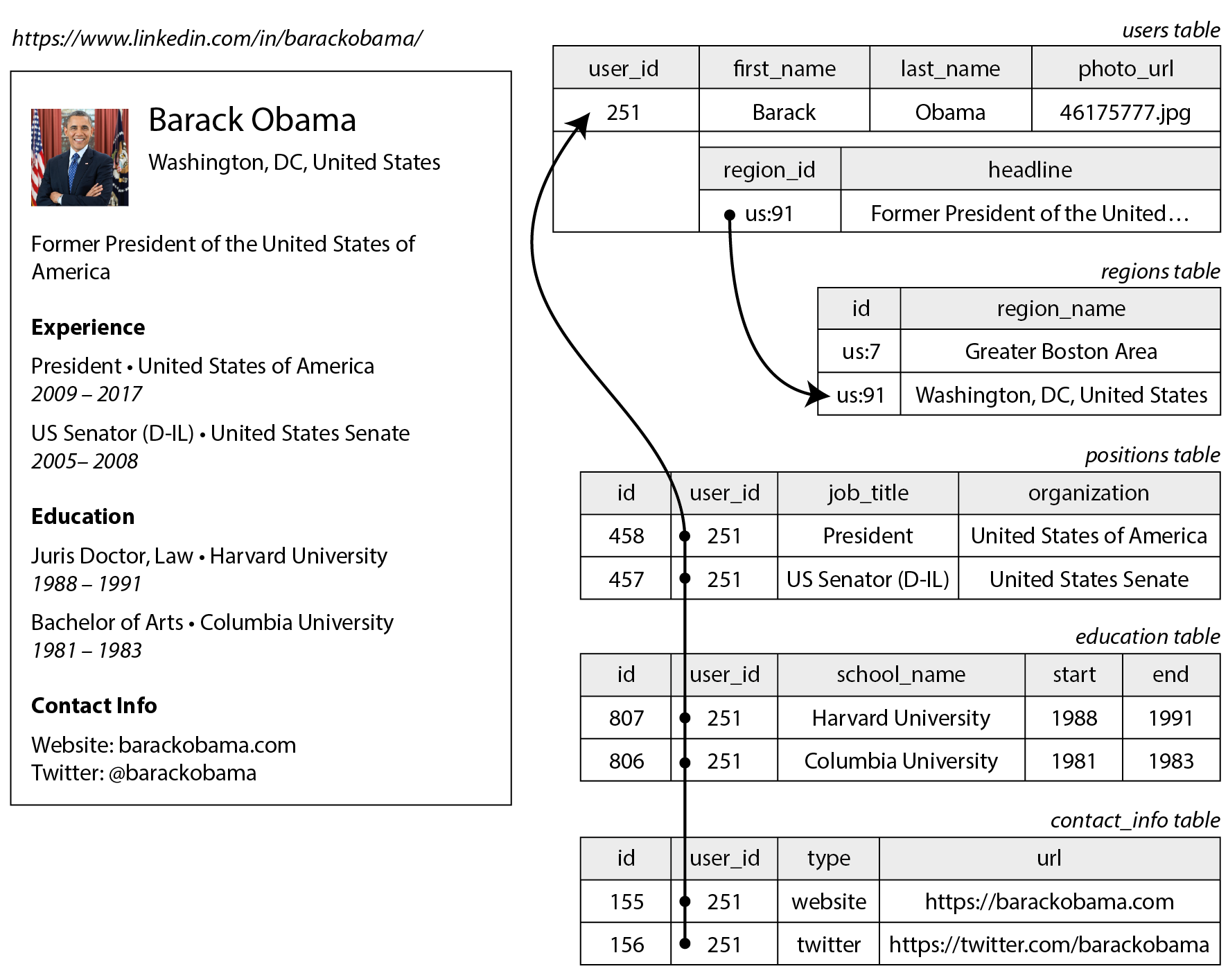

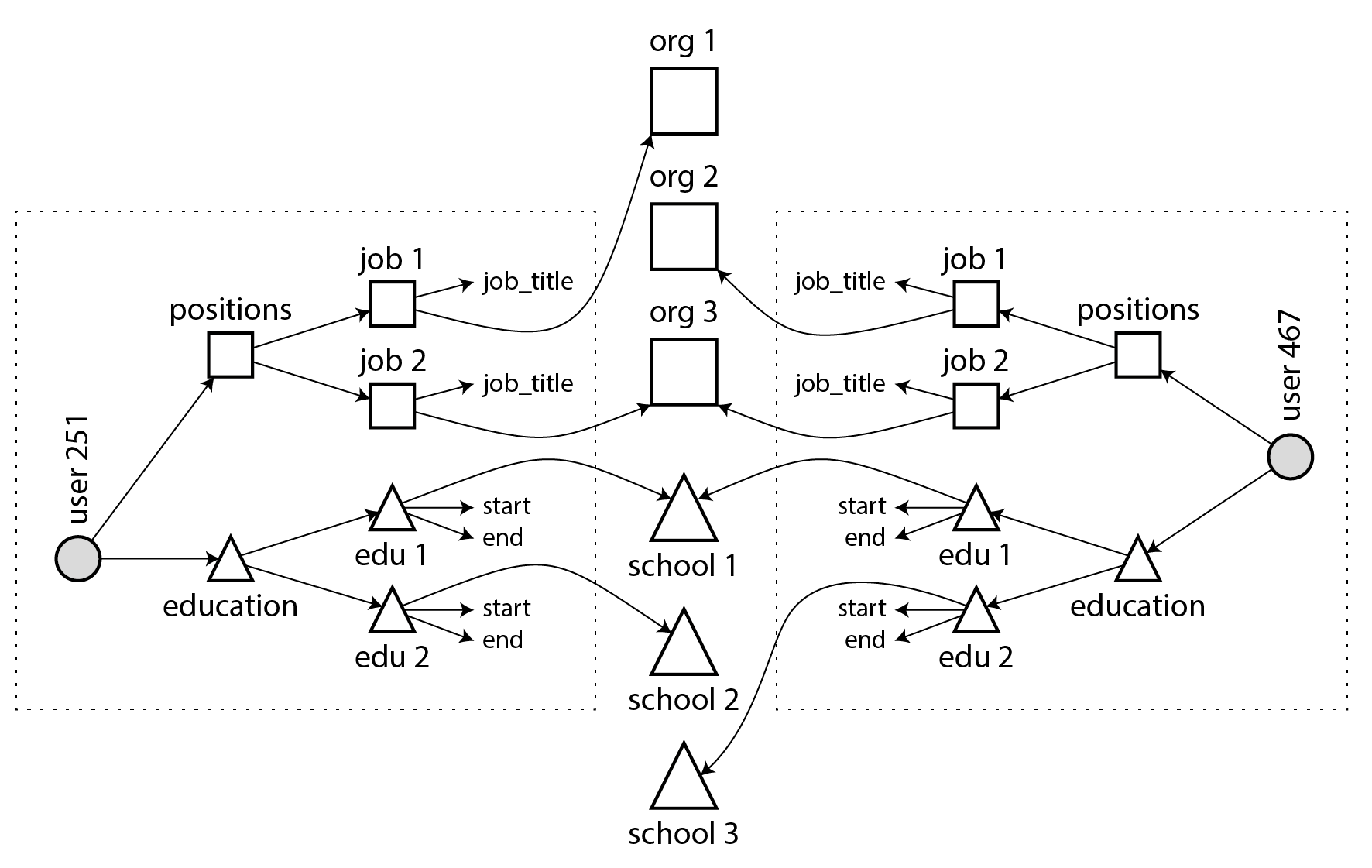

Not all data lends itself well to a relational representation; let’s look at an example to explore a limitation of the relational model. Figure 3-1 illustrates how a résumé (a LinkedIn profile) could be expressed in a relational schema. The profile as a whole can be identified by a unique identifier, user_id. Fields like first_name and last_name appear exactly once per user, so they can be modeled as columns on the users table.

Most people have had more than one job in their career (positions), and people may have varying numbers of periods of education and any number of pieces of contact information. One way of representing such one-to-many relationships is to put positions, education, and contact information in separate tables, with a foreign key reference to the users table, as in Figure 3-1.

Figure 3-1. Representing a LinkedIn profile using a relational schema.

Another way of representing the same information, which is perhaps more natural and maps more closely to an object structure in application code, is as a JSON document as shown in Example 3-1.

Example 3-1. Representing a LinkedIn profile as a JSON document

{

"user_id": 251,

"first_name": "Barack",

"last_name": "Obama",

"headline": "Former President of the United States of America",

"region_id": "us:91",

"photo_url": "/p/7/000/253/05b/308dd6e.jpg",

"positions": [

{"job_title": "President", "organization": "United States of America"},

{"job_title": "US Senator (D-IL)", "organization": "United States Senate"}

],

"education": [

{"school_name": "Harvard University", "start": 1988, "end": 1991},

{"school_name": "Columbia University", "start": 1981, "end": 1983}

],

"contact_info": {

"website": "https://barackobama.com",

"twitter": "https://twitter.com/barackobama"

}

}

Some developers feel that the JSON model reduces the impedance mismatch between the application code and the storage layer. However, as we shall see in [Link to Come], there are also problems with JSON as a data encoding format. The lack of a schema is often cited as an advantage; we will discuss this in “Schema flexibility in the document model”.

The JSON representation has better locality than the multi-table schema in Figure 3-1 (see “Data locality for reads and writes”). If you want to fetch a profile in the relational example, you need to either perform multiple queries (query each table by user_id) or perform a messy multi-way join between the users table and its subordinate tables [8]. In the JSON representation, all the relevant information is in one place, making the query both faster and simpler.

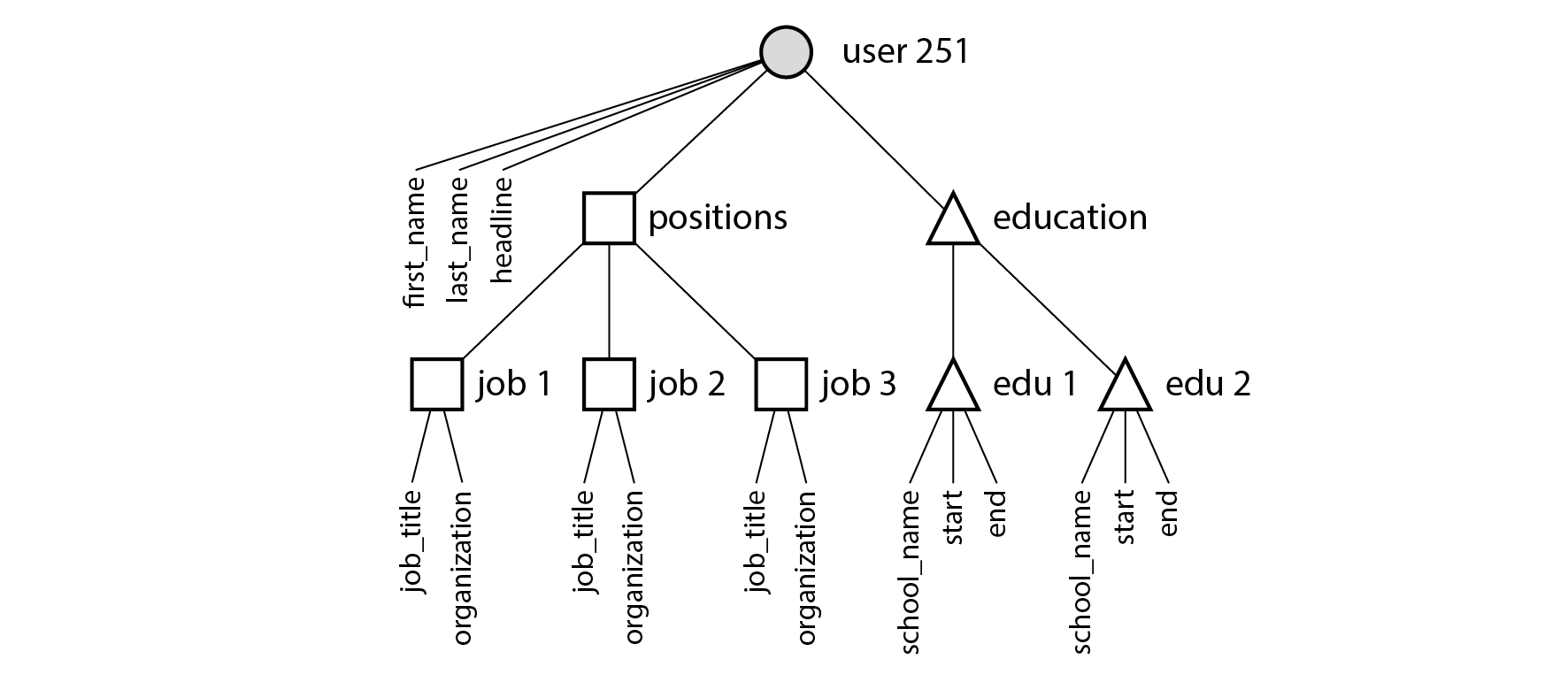

The one-to-many relationships from the user profile to the user’s positions, educational history, and contact information imply a tree structure in the data, and the JSON representation makes this tree structure explicit (see Figure 3-2).

Figure 3-2. One-to-many relationships forming a tree structure.

注意

This type of relationship is sometimes called one-to-few rather than one-to-many, since a résumé typically has a small number of positions [9, 10]. In sitations where there may be a genuinely large number of related items—say, comments on a celebrity’s social media post, of which there could be many thousands—embedding them all in the same document may be too unwieldy, so the relational approach in Figure 3-1 is preferable.

范式化,反范式化,连接

In Example 3-1 in the preceding section, region_id is given as an ID, not as the plain-text string "Washington, DC, United States". Why?

If the user interface has a free-text field for entering the region, it makes sense to store it as a plain-text string. But there are advantages to having standardized lists of geographic regions, and letting users choose from a drop-down list or autocompleter:

- Consistent style and spelling across profiles

- Avoiding ambiguity if there are several places with the same name (if the string were just “Washington”, would it refer to DC or to the state?)

- Ease of updating—the name is stored in only one place, so it is easy to update across the board if it ever needs to be changed (e.g., change of a city name due to political events)

- Localization support—when the site is translated into other languages, the standardized lists can be localized, so the region can be displayed in the viewer’s language

- Better search—e.g., a search for people on the US East Coast can match this profile, because the list of regions can encode the fact that Washington is located on the East Coast (which is not apparent from the string

"Washington, DC")

Whether you store an ID or a text string is a question of normalization. When you use an ID, your data is more normalized: the information that is meaningful to humans (such as the text Washington, DC) is stored in only one place, and everything that refers to it uses an ID (which only has meaning within the database). When you store the text directly, you are duplicating the human-meaningful information in every record that uses it; this representation is denormalized.

The advantage of using an ID is that because it has no meaning to humans, it never needs to change: the ID can remain the same, even if the information it identifies changes. Anything that is meaningful to humans may need to change sometime in the future—and if that information is duplicated, all the redundant copies need to be updated. That requires more code, more write operations, and risks inconsistencies (where some copies of the information are updated but others aren’t).

The downside of a normalized representation is that every time you want to display a record containing an ID, you have to do an additional lookup to resolve the ID into something human-readable. In a relational data model, this is done using a join, for example:

SELECT users.*, regions.region_name

FROM users

JOIN regions ON users.region_id = regions.id

WHERE users.id = 251;

In a document database, it is more common to either use a denormalized representation that needs no join when reading, or to perform the join in application code—that is, you first fetch a document containing an ID, and then perform a second query to resolve that ID into another document. In MongoDB, it is also possible to perform a join using the $lookup operator in an aggregation pipeline:

db.users.aggregate([

{ $match: { _id: 251 } },

{ $lookup: {

from: "regions",

localField: "region_id",

foreignField: "_id",

as: "region"

} }

])

Trade-offs of normalization

In the résumé example, while the region_id field is a reference into a standardized set of regions, the name of the organization (the company or government where the person worked) and school_name (where they studied) are just strings. This representation is denormalized: many people may have worked at the same company, but there is no ID linking them.

Perhaps the organization and school should be entities instead, and the profile should reference their IDs instead of their names? The same arguments for referencing the ID of a region also apply here. For example, say we wanted to include the logo of the school or company in addition to their name:

- In a denormalized representation, we would include the image URL of the logo on every individual person’s profile; this makes the JSON document self-contained, but it creates a headache if we ever need to change the logo, because we now need to find all of the occurrences of the old URL and update them [9].

- In a normalized representation, we would create an entity representing an organization or school, and store its name, logo URL, and perhaps other attributes (description, news feed, etc.) once on that entity. Every résumé that mentions the organization would then simply reference its ID, and updating the logo is easy.

As a general principle, normalized data is usually faster to write (since there is only one copy), but slower to query (since it requires joins); denormalized data is usually faster to read (fewer joins), but more expensive to write (more copies to update). You might find it helpful to view denormalization as a form of derived data (“Systems of Record and Derived Data”), since you need to set up a process for updating the redundant copies of the data.

Besides the cost of performing all these updates, you also need to consider the consistency of the database if a process crashes halfway through making its updates. Databases that offer atomic transactions (see [Link to Come]) make it easier to remain consistent, but not all databases offer atomicity across multiple documents. It is also possible to ensure consistency through stream processing, which we discuss in [Link to Come].

Normalization tends to be better for OLTP systems, where both reads and updates need to be fast; analytics systems often fare better with denormalized data, since they perform updates in bulk, and the performance of read-only queries is the dominant concern. Moreover, in systems of small to moderate scale, a normalized data model is often best, because you don’t have to worry about keeping multiple copies of the data consistent with each other, and the cost of performing joins is acceptable. However, in very large-scale systems, the cost of joins can become problematic.

Denormalization in the social networking case study

In “Case Study: Social Network Home Timelines” we compared a normalized representation (Figure 2-1) and a denormalized one (precomputed, materialized timelines): here, the join between posts and follows was too expensive, and the materialized timeline is a cache of the result of that join. The fan-out process that inserts a new post into followers’ timelines was our way of keeping the denormalized representation consistent.

However, the implementation of materialized timelines at X (formerly Twitter) does not store the actual text of each post: each entry actually only stores the post ID, the ID of the user who posted it, and a little bit of extra information to identify reposts and replies [11]. In other words, it is a precomputed result of (approximately) the following query:

SELECT posts.id, posts.sender_id FROM posts

JOIN follows ON posts.sender_id = follows.followee_id

WHERE follows.follower_id = current_user

ORDER BY posts.timestamp DESC

LIMIT 1000

This means that whenever the timeline is read, the service still needs to perform two joins: look up the post ID to fetch the actual post content (as well as statistics such as the number of likes and replies), and look up the sender’s profile by ID (to get their username, profile picture, and other details). This process of looking up the human-readable information by ID is called hydrating the IDs, and it is essentially a join performed in application code [11].

The reason for storing only IDs in the precomputed timeline is that the data they refer to is fast-changing: the number of likes and replies may change multiple times per second on a popular post, and some users regularly change their username or profile photo. Since the timeline should show the latest like count and profile picture when it is viewed, it would not make sense to denormalize this information into the materialized timeline. Moreover, the storage cost would be increased significantly by such denormalization.

This example shows that having to perform joins when reading data is not, as sometimes claimed, an impediment to creating high-performance, scalable services. Hydrating post ID and user ID is actually a fairly easy operation to scale, since it parallelizes well, and the cost doesn’t depend on the number of accounts you are following or the number of followers you have.

If you need to decide whether to denormalize something in your application, the social network case study shows that the choice is not immediately obvious: the most scalable approach may involve denormalizing some things and leaving other things normalized. You will have to carefully consider how often the information changes, and the cost of reads and writes (which might be dominated by outliers, such as users with many follows/followers in the case of a typical social network). Normalization and denormalization are not inherently good or bad—they are just a trade-off in terms of performance of reads and writes, as well as the amount of effort to implement.

多对一与多对多关系

While positions and education in Figure 3-1 are examples of one-to-many or one-to-few relationships (one résumé has several positions, but each position belongs only to one résumé), the region_id field is an example of a many-to-one relationship (many people live in the same region, but we assume that each person lives in only one region at any one time).

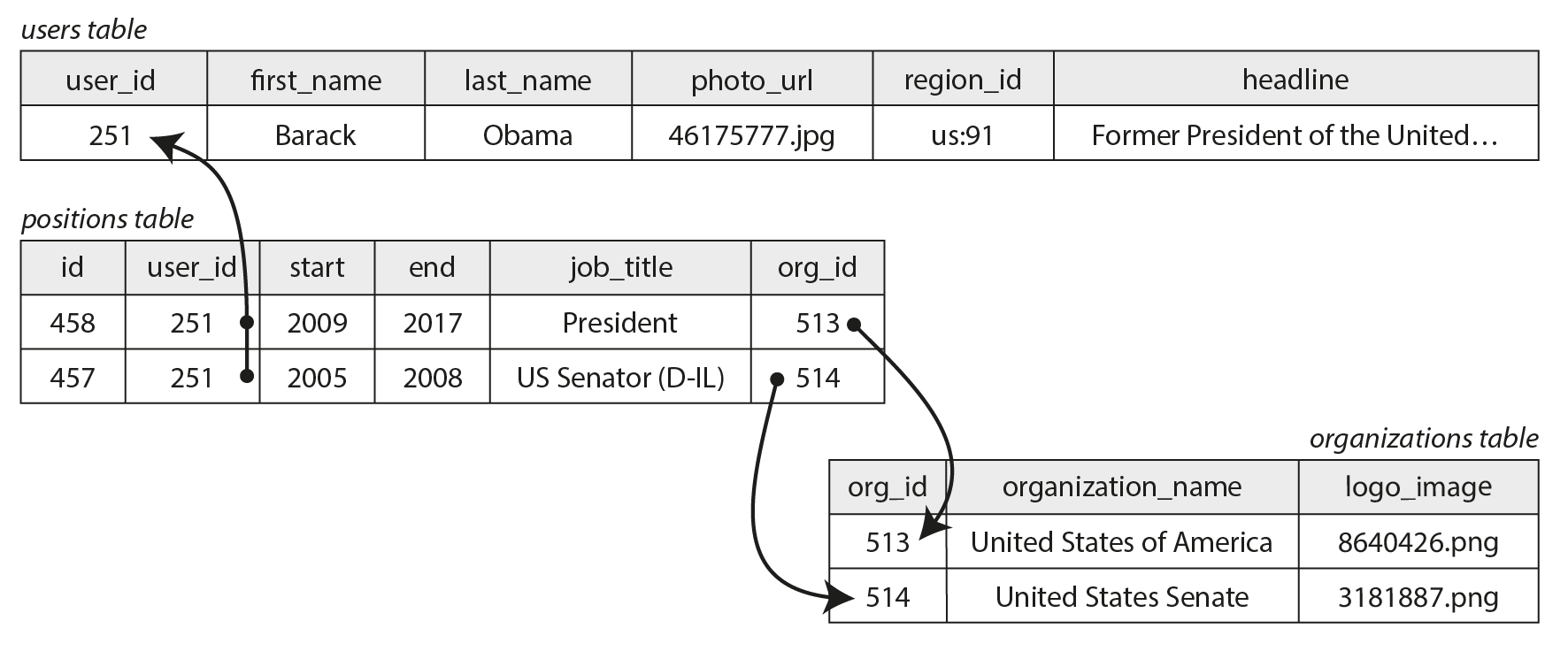

If we introduce entities for organizations and schools, and reference them by ID from the résumé, then we also have many-to-many relationships (one person has worked for several organizations, and an organization has several past or present employees). In a relational model, such a relationship is usually represented as an associative table or join table, as shown in Figure 3-3: each position associates one user ID with one organization ID.

Figure 3-3. Many-to-many relationships in the relational model.

Many-to-one and many-to-many relationships do not easily fit within one self-contained JSON document; they lend themselves more to a normalized representation. In a document model, one possible representation is given in Example 3-2 and illustrated in Figure 3-4: the data within each dotted rectangle can be grouped into one document, but the links to organizations and schools are best represented as references to other documents.

Example 3-2. A résumé that references organizations by ID.

{

"user_id": 251,

"first_name": "Barack",

"last_name": "Obama",

"positions": [

{"start": 2009, "end": 2017, "job_title": "President", "org_id": 513},

{"start": 2005, "end": 2008, "job_title": "US Senator (D-IL)", "org_id": 514}

],

...

}

Figure 3-4. Many-to-many relationships in the document model: the data within each dotted box can be grouped into one document.

Many-to-many relationships often need to be queried in “both directions”: for example, finding all of the organizations that a particular person has worked for, and finding all of the people who have worked at a particular organization. One way of enabling such queries is to store ID references on both sides, i.e., a résumé includes the ID of each organization where the person has worked, and the organization document includes the IDs of the résumés that mention that organization. This representation is denormalized, since the relationship is stored in two places, which could become inconsistent with each other.

A normalized representation stores the relationship in only one place, and relies on secondary indexes (which we discuss in [Link to Come]) to allow the relationship to be efficiently queried in both directions. In the relational schema of Figure 3-3, we would tell the database to create indexes on both the user_id and the org_id columns of the positions table.

In the document model of Example 3-2, the database needs to index the org_id field of objects inside the positions array. Many document databases and relational databases with JSON support are able to create such indexes on values inside a document.

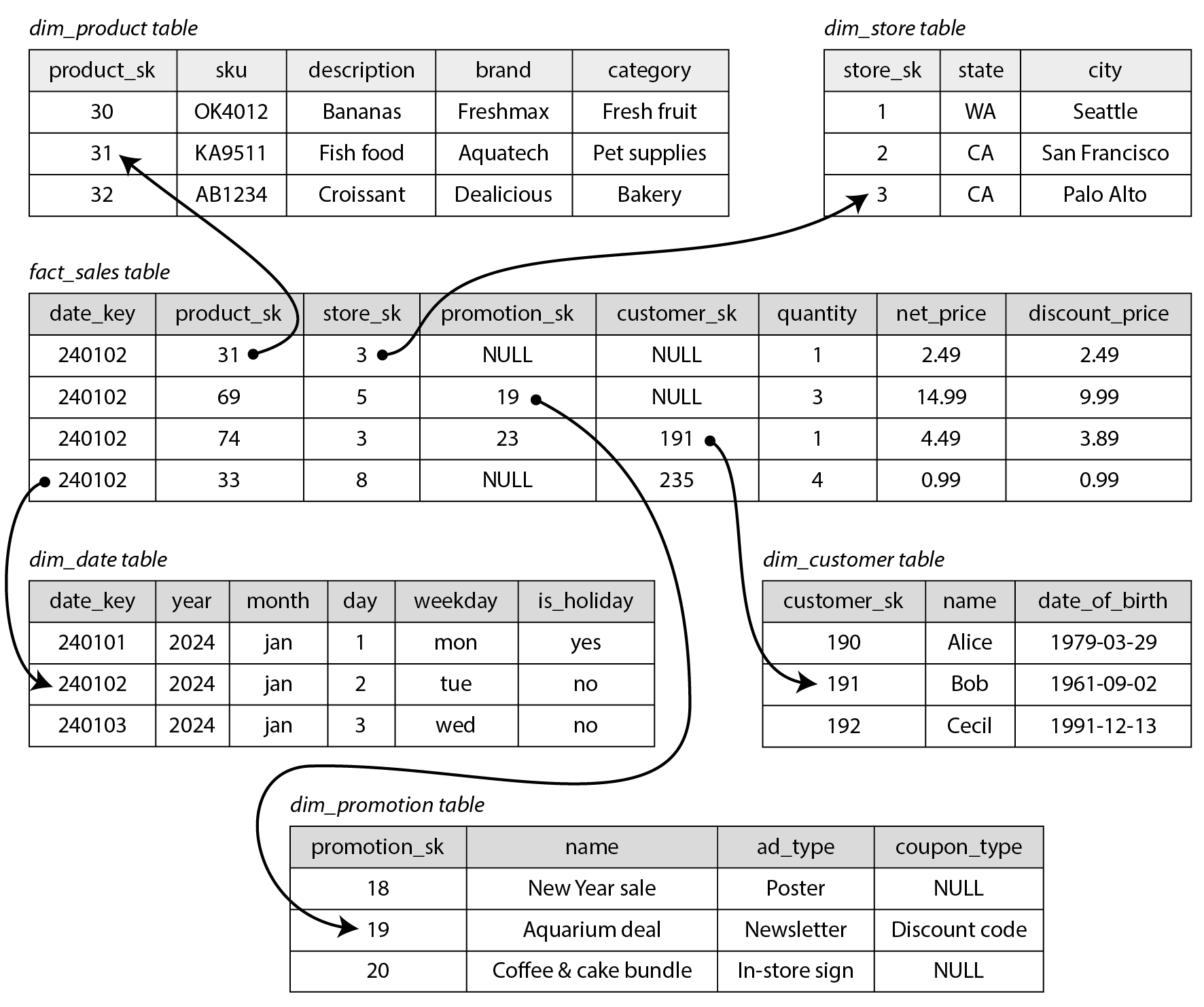

Stars and Snowflakes: Schemas for Analytics

Data warehouses (see “Data Warehousing”) are usually relational, and there are a few widely-used conventions for the structure of tables in a data warehouse: a star schema, snowflake schema, dimensional modeling [12], and one big table (OBT). These structures are optimized for the needs of business analysts. ETL processes translate data from operational systems into this schema.

The example schema in Figure 3-5 shows a data warehouse that might be found at a grocery retailer. At the center of the schema is a so-called fact table (in this example, it is called fact_sales). Each row of the fact table represents an event that occurred at a particular time (here, each row represents a customer’s purchase of a product). If we were analyzing website traffic rather than retail sales, each row might represent a page view or a click by a user.

Figure 3-5. Example of a star schema for use in a data warehouse.

Usually, facts are captured as individual events, because this allows maximum flexibility of analysis later. However, this means that the fact table can become extremely large. A big enterprise may have many petabytes of transaction history in its data warehouse, mostly represented as fact tables.

Some of the columns in the fact table are attributes, such as the price at which the product was sold and the cost of buying it from the supplier (allowing the profit margin to be calculated). Other columns in the fact table are foreign key references to other tables, called dimension tables. As each row in the fact table represents an event, the dimensions represent the who, what, where, when, how, and why of the event.

For example, in Figure 3-5, one of the dimensions is the product that was sold. Each row in the dim_product table represents one type of product that is for sale, including its stock-keeping unit (SKU), description, brand name, category, fat content, package size, etc. Each row in the fact_sales table uses a foreign key to indicate which product was sold in that particular transaction. Queries often involve multiple joins to multiple dimension tables.

Even date and time are often represented using dimension tables, because this allows additional information about dates (such as public holidays) to be encoded, allowing queries to differentiate between sales on holidays and non-holidays.

Figure 3-5 is an example of a star schema. The name comes from the fact that when the table relationships are visualized, the fact table is in the middle, surrounded by its dimension tables; the connections to these tables are like the rays of a star.

A variation of this template is known as the snowflake schema, where dimensions are further broken down into subdimensions. For example, there could be separate tables for brands and product categories, and each row in the dim_product table could reference the brand and category as foreign keys, rather than storing them as strings in the dim_product table. Snowflake schemas are more normalized than star schemas, but star schemas are often preferred because they are simpler for analysts to work with [12].

In a typical data warehouse, tables are often quite wide: fact tables often have over 100 columns, sometimes several hundred. Dimension tables can also be wide, as they include all the metadata that may be relevant for analysis—for example, the dim_store table may include details of which services are offered at each store, whether it has an in-store bakery, the square footage, the date when the store was first opened, when it was last remodeled, how far it is from the nearest highway, etc.

A star or snowflake schema consists mostly of many-to-one relationships (e.g., many sales occur for one particular product, in one particular store), represented as the fact table having foreign keys into dimension tables, or dimensions into sub-dimensions. In principle, other types of relationship could exist, but they are often denormalized in order to simplify queries. For example, if a customer buys several different products at once, that multi-item transaction is not represented explicitly; instead, there is a separate row in the fact table for each product purchased, and those facts all just happen to have the same customer ID, store ID, and timestamp.

Some data warehouse schemas take denormalization even further and leave out the dimension tables entirely, folding the information in the dimensions into denormalized columns on the fact table instead (essentially, precomputing the join between the fact table and the dimension tables). This approach is known as one big table (OBT), and while it requires more storage space, it sometimes enables faster queries [13].

In the context of analytics, such denormalization is unproblematic, since the data typically represents a log of historical data that is not going to change (except maybe for occasionally correcting an error). The issues of data consistency and write overheads that occur with denormalization in OLTP systems are not as pressing in analytics.

When to Use Which Model

The main arguments in favor of the document data model are schema flexibility, better performance due to locality, and that for some applications it is closer to the object model used by the application. The relational model counters by providing better support for joins, many-to-one, and many-to-many relationships. Let’s examine these arguments in more detail.

If the data in your application has a document-like structure (i.e., a tree of one-to-many relationships, where typically the entire tree is loaded at once), then it’s probably a good idea to use a document model. The relational technique of shredding—splitting a document-like structure into multiple tables (like positions, education, and contact_info in Figure 3-1)—can lead to cumbersome schemas and unnecessarily complicated application code.

The document model has limitations: for example, you cannot refer directly to a nested item within a document, but instead you need to say something like “the second item in the list of positions for user 251”. If you do need to reference nested items, a relational approach works better, since you can refer to any item directly by its ID.

Some applications allow the user to choose the order of items: for example, imagine a to-do list or issue tracker where the user can drag and drop tasks to reorder them. The document model supports such applications well, because the items (or their IDs) can simply be stored in a JSON array to determine their order. In relational databases there isn’t a standard way of representing such reorderable lists, and various tricks are used: sorting by an integer column (requiring renumbering when you insert into the middle), a linked list of IDs, or fractional indexing [14, 15, 16].

Schema flexibility in the document model

Most document databases, and the JSON support in relational databases, do not enforce any schema on the data in documents. XML support in relational databases usually comes with optional schema validation. No schema means that arbitrary keys and values can be added to a document, and when reading, clients have no guarantees as to what fields the documents may contain.

Document databases are sometimes called schemaless, but that’s misleading, as the code that reads the data usually assumes some kind of structure—i.e., there is an implicit schema, but it is not enforced by the database [17]. A more accurate term is schema-on-read (the structure of the data is implicit, and only interpreted when the data is read), in contrast with schema-on-write (the traditional approach of relational databases, where the schema is explicit and the database ensures all data conforms to it when the data is written) [18].

Schema-on-read is similar to dynamic (runtime) type checking in programming languages, whereas schema-on-write is similar to static (compile-time) type checking. Just as the advocates of static and dynamic type checking have big debates about their relative merits [19], enforcement of schemas in database is a contentious topic, and in general there’s no right or wrong answer.

The difference between the approaches is particularly noticeable in situations where an application wants to change the format of its data. For example, say you are currently storing each user’s full name in one field, and you instead want to store the first name and last name separately [20]. In a document database, you would just start writing new documents with the new fields and have code in the application that handles the case when old documents are read. For example:

if (user && user.name && !user.first_name) {

// Documents written before Dec 8, 2023 don't have first_name

user.first_name = user.name.split(" ")[0];

}

The downside of this approach is that every part of your application that reads from the database now needs to deal with documents in old formats that may have been written a long time in the past. On the other hand, in a schema-on-write database, you would typically perform a migration along the lines of:

ALTER TABLE users ADD COLUMN first_name text DEFAULT NULL;

UPDATE users SET first_name = split_part(name, ' ', 1); -- PostgreSQL

UPDATE users SET first_name = substring_index(name, ' ', 1); -- MySQL

In most relational databases, adding a column with a default value is fast and unproblematic, even on large tables. However, running the UPDATE statement is likely to be slow on a large table, since every row needs to be rewritten, and other schema operations (such as changing the data type of a column) also typically require the entire table to be copied.

Various tools exist to allow this type of schema changes to be performed in the background without downtime [21, 22, 23, 24], but performing such migrations on large databases remains operationally challenging. Complicated migrations can be avoided by only adding the first_name column with a default value of NULL (which is fast), and filling it in at read time, like you would with a document database.

The schema-on-read approach is advantageous if the items in the collection don’t all have the same structure for some reason (i.e., the data is heterogeneous)—for example, because:

- There are many different types of objects, and it is not practicable to put each type of object in its own table.

- The structure of the data is determined by external systems over which you have no control and which may change at any time.

In situations like these, a schema may hurt more than it helps, and schemaless documents can be a much more natural data model. But in cases where all records are expected to have the same structure, schemas are a useful mechanism for documenting and enforcing that structure. We will discuss schemas and schema evolution in more detail in [Link to Come].

Data locality for reads and writes

A document is usually stored as a single continuous string, encoded as JSON, XML, or a binary variant thereof (such as MongoDB’s BSON). If your application often needs to access the entire document (for example, to render it on a web page), there is a performance advantage to this storage locality. If data is split across multiple tables, like in Figure 3-1, multiple index lookups are required to retrieve it all, which may require more disk seeks and take more time.

The locality advantage only applies if you need large parts of the document at the same time. The database typically needs to load the entire document, which can be wasteful if you only need to access a small part of a large document. On updates to a document, the entire document usually needs to be rewritten. For these reasons, it is generally recommended that you keep documents fairly small and avoid frequent small updates to a document.

However, the idea of storing related data together for locality is not limited to the document model. For example, Google’s Spanner database offers the same locality properties in a relational data model, by allowing the schema to declare that a table’s rows should be interleaved (nested) within a parent table [25]. Oracle allows the same, using a feature called multi-table index cluster tables [26]. The column-family concept in the Bigtable data model (used in Cassandra, HBase, and ScyllaDB), also known as a wide-column model, has a similar purpose of managing locality [27].

Query languages for documents

Another difference between a relational and a document database is the language or API that you use to query it. Most relational databases are queried using SQL, but document databases are more varied. Some allow only key-value access by primary key, while others also offer secondary indexes to query for values inside documents, and some provide rich query languages.

XML databases are often queried using XQuery and XPath, which are designed to allow complex queries, including joins across multiple documents, and also format their results as XML [28]. JSON Pointer [29] and JSONPath [30] provide an equivalent to XPath for JSON. MongoDB’s aggregation pipeline, whose $lookup operator for joins we saw in “Normalization, Denormalization, and Joins”, is an example of a query language for collections of JSON documents.

Let’s look at another example to get a feel for this language—this time an aggregation, which is especially needed for analytics. Imagine you are a marine biologist, and you add an observation record to your database every time you see animals in the ocean. Now you want to generate a report saying how many sharks you have sighted per month. In PostgreSQL you might express that query like this:

SELECT date_trunc('month', observation_timestamp) AS observation_month,

sum(num_animals) AS total_animals

FROM observations

WHERE family = 'Sharks'

GROUP BY observation_month;

-

The

date_trunc('month', timestamp)function determines the calendar month containingtimestamp, and returns another timestamp representing the beginning of that month. In other words, it rounds a timestamp down to the nearest month.

This query first filters the observations to only show species in the Sharks family, then groups the observations by the calendar month in which they occurred, and finally adds up the number of animals seen in all observations in that month. The same query can be expressed using MongoDB’s aggregation pipeline as follows:

db.observations.aggregate([

{ $match: { family: "Sharks" } },

{ $group: {

_id: {

year: { $year: "$observationTimestamp" },

month: { $month: "$observationTimestamp" }

},

totalAnimals: { $sum: "$numAnimals" }

} }

]);

The aggregation pipeline language is similar in expressiveness to a subset of SQL, but it uses a JSON-based syntax rather than SQL’s English-sentence-style syntax; the difference is perhaps a matter of taste.

Convergence of document and relational databases

Document databases and relational databases started out as very different approaches to data management, but they have grown more similar over time. Relational databases added support for JSON types and query operators, and the ability to index properties inside documents. Some document databases (such as MongoDB, Couchbase, and RethinkDB) added support for joins, secondary indexes, and declarative query languages.

This convergence of the models is good news for application developers, because the relational model and the document model work best when you can combine both in the same database. Many document databases need relational-style references to other documents, and many relational databases have sections where schema flexibility is beneficial. Relational-document hybrids are a powerful combination.

注意

Codd’s original description of the relational model [3] actually allowed something similar to JSON within a relational schema. He called it nonsimple domains. The idea was that a value in a row doesn’t have to just be a primitive datatype like a number or a string, but it could also be a nested relation (table)—so you can have an arbitrarily nested tree structure as a value, much like the JSON or XML support that was added to SQL over 30 years later.

类图数据模型

We saw earlier that the type of relationships is an important distinguishing feature between different data models. If your application has mostly one-to-many relationships (tree-structured data) and few other relationships between records, the document model is appropriate.

But what if many-to-many relationships are very common in your data? The relational model can handle simple cases of many-to-many relationships, but as the connections within your data become more complex, it becomes more natural to start modeling your data as a graph.

A graph consists of two kinds of objects: vertices (also known as nodes or entities) and edges (also known as relationships or arcs). Many kinds of data can be modeled as a graph. Typical examples include:

-

Social graphs

Vertices are people, and edges indicate which people know each other.

-

The web graph

Vertices are web pages, and edges indicate HTML links to other pages.

-

Road or rail networks

Vertices are junctions, and edges represent the roads or railway lines between them.

Well-known algorithms can operate on these graphs: for example, map navigation apps search for the shortest path between two points in a road network, and PageRank can be used on the web graph to determine the popularity of a web page and thus its ranking in search results [31].

Graphs can be represented in several different ways. In the adjacency list model, each vertex stores the IDs of its neighbor vertices that are one edge away. Alternatively, you can use an adjacency matrix, a two-dimensional array where each row and each column corresponds to a vertex, where the value is zero when there is no edge between the row vertex and the column vertex, and where the value is one if there is an edge. The adjacency list is good for graph traversals, and the matrix is good for machine learning (see “Dataframes, Matrices, and Arrays”).

In the examples just given, all the vertices in a graph represent the same kind of thing (people, web pages, or road junctions, respectively). However, graphs are not limited to such homogeneous data: an equally powerful use of graphs is to provide a consistent way of storing completely different types of objects in a single database. For example:

- Facebook maintains a single graph with many different types of vertices and edges: vertices represent people, locations, events, checkins, and comments made by users; edges indicate which people are friends with each other, which checkin happened in which location, who commented on which post, who attended which event, and so on [32].

- Knowledge graphs are used by search engines to record facts about entities that often occur in search queries, such as organizations, people, and places [33]. This information is obtained by crawling and analyzing the text on websites; some websites, such as Wikidata, also publish graph data in a structured form.

There are several different, but related, ways of structuring and querying data in graphs. In this section we will discuss the property graph model (implemented by Neo4j, Memgraph, KùzuDB [34], and others [35]) and the triple-store model (implemented by Datomic, AllegroGraph, Blazegraph, and others). These models are fairly similar in what they can express, and some graph databases (such as Amazon Neptune) support both models.

We will also look at four query languages for graphs (Cypher, SPARQL, Datalog, and GraphQL), as well as SQL support for querying graphs. Other graph query languages exist, such as Gremlin [36], but these will give us a representative overview.

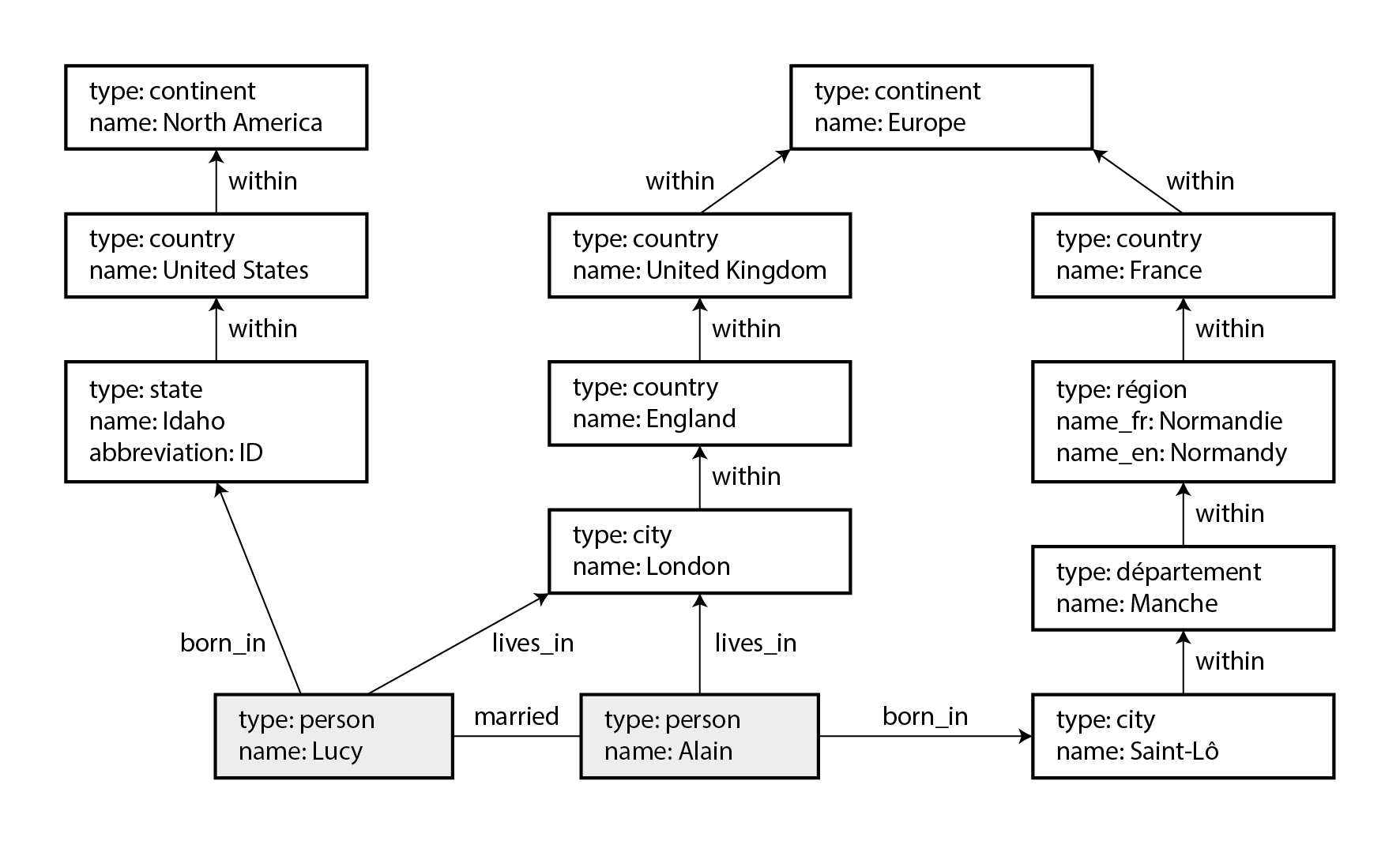

To illustrate these different languages and models, this section uses the graph shown in Figure 3-6 as running example. It could be taken from a social network or a genealogical database: it shows two people, Lucy from Idaho and Alain from Saint-Lô, France. They are married and living in London. Each person and each location is represented as a vertex, and the relationships between them as edges. This example will help demonstrate some queries that are easy in graph databases, but difficult in other models.

Figure 3-6. Example of graph-structured data (boxes represent vertices, arrows represent edges).

属性图

In the property graph (also known as labeled property graph) model, each vertex consists of:

- A unique identifier

- A label (string) to describe what type of object this vertex represents

- A set of outgoing edges

- A set of incoming edges

- A collection of properties (key-value pairs)

Each edge consists of:

- A unique identifier

- The vertex at which the edge starts (the tail vertex)

- The vertex at which the edge ends (the head vertex)

- A label to describe the kind of relationship between the two vertices

- A collection of properties (key-value pairs)

You can think of a graph store as consisting of two relational tables, one for vertices and one for edges, as shown in Example 3-3 (this schema uses the PostgreSQL jsonb datatype to store the properties of each vertex or edge). The head and tail vertex are stored for each edge; if you want the set of incoming or outgoing edges for a vertex, you can query the edges table by head_vertex or tail_vertex, respectively.

Example 3-3. Representing a property graph using a relational schema

CREATE TABLE vertices (

vertex_id integer PRIMARY KEY,

label text,

properties jsonb

);

CREATE TABLE edges (

edge_id integer PRIMARY KEY,

tail_vertex integer REFERENCES vertices (vertex_id),

head_vertex integer REFERENCES vertices (vertex_id),

label text,

properties jsonb

);

CREATE INDEX edges_tails ON edges (tail_vertex);

CREATE INDEX edges_heads ON edges (head_vertex);

Some important aspects of this model are:

- Any vertex can have an edge connecting it with any other vertex. There is no schema that restricts which kinds of things can or cannot be associated.

- Given any vertex, you can efficiently find both its incoming and its outgoing edges, and thus traverse the graph—i.e., follow a path through a chain of vertices—both forward and backward. (That’s why Example 3-3 has indexes on both the

tail_vertexandhead_vertexcolumns.) - By using different labels for different kinds of vertices and relationships, you can store several different kinds of information in a single graph, while still maintaining a clean data model.

The edges table is like the many-to-many associative table/join table we saw in “Many-to-One and Many-to-Many Relationships”, generalized to allow many different types of relationship to be stored in the same table. There may also be indexes on the labels and the properties, allowing vertices or edges with certain properties to be found efficiently.

Note

A limitation of graph models is that an edge can only associate two vertices with each other, whereas a relational join table can represent three-way or even higher-degree relationships by having multiple foreign key references on a single row. Such relationships can be represented in a graph by creating an additional vertex corresponding to each row of the join table, and edges to/from that vertex, or by using a hypergraph.

Those features give graphs a great deal of flexibility for data modeling, as illustrated in Figure 3-6. The figure shows a few things that would be difficult to express in a traditional relational schema, such as different kinds of regional structures in different countries (France has départements and régions, whereas the US has counties and states), quirks of history such as a country within a country (ignoring for now the intricacies of sovereign states and nations), and varying granularity of data (Lucy’s current residence is specified as a city, whereas her place of birth is specified only at the level of a state).

You could imagine extending the graph to also include many other facts about Lucy and Alain, or other people. For instance, you could use it to indicate any food allergies they have (by introducing a vertex for each allergen, and an edge between a person and an allergen to indicate an allergy), and link the allergens with a set of vertices that show which foods contain which substances. Then you could write a query to find out what is safe for each person to eat. Graphs are good for evolvability: as you add features to your application, a graph can easily be extended to accommodate changes in your application’s data structures.

Cypher查询语言

Cypher is a query language for property graphs, originally created for the Neo4j graph database, and later developed into an open standard as openCypher [37]. Besides Neo4j, Cypher is supported by Memgraph, KùzuDB [34], Amazon Neptune, Apache AGE (with storage in PostgreSQL), and others. It is named after a character in the movie The Matrix and is not related to ciphers in cryptography [38].

Example 3-4 shows the Cypher query to insert the lefthand portion of Figure 3-6 into a graph database. The rest of the graph can be added similarly. Each vertex is given a symbolic name like usa or idaho. That name is not stored in the database, but only used internally within the query to create edges between the vertices, using an arrow notation: (idaho) -[:WITHIN]-> (usa) creates an edge labeled WITHIN, with idaho as the tail node and usa as the head node.

Example 3-4. A subset of the data in Figure 3-6, represented as a Cypher query

CREATE

(namerica :Location {name:'North America', type:'continent'}),

(usa :Location {name:'United States', type:'country' }),

(idaho :Location {name:'Idaho', type:'state' }),

(lucy :Person {name:'Lucy' }),

(idaho) -[:WITHIN ]-> (usa) -[:WITHIN]-> (namerica),

(lucy) -[:BORN_IN]-> (idaho)

When all the vertices and edges of Figure 3-6 are added to the database, we can start asking interesting questions: for example, find the names of all the people who emigrated from the United States to Europe. That is, find all the vertices that have a BORN_IN edge to a location within the US, and also a LIVING_IN edge to a location within Europe, and return the name property of each of those vertices.

Example 3-5 shows how to express that query in Cypher. The same arrow notation is used in a MATCH clause to find patterns in the graph: (person) -[:BORN_IN]-> () matches any two vertices that are related by an edge labeled BORN_IN. The tail vertex of that edge is bound to the variable person, and the head vertex is left unnamed.

Example 3-5. Cypher query to find people who emigrated from the US to Europe

MATCH

(person) -[:BORN_IN]-> () -[:WITHIN*0..]-> (:Location {name:'United States'}),

(person) -[:LIVES_IN]-> () -[:WITHIN*0..]-> (:Location {name:'Europe'})

RETURN person.name

The query can be read as follows:

Find any vertex (call it

person) that meets both of the following conditions:

personhas an outgoingBORN_INedge to some vertex. From that vertex, you can follow a chain of outgoingWITHINedges until eventually you reach a vertex of typeLocation, whosenameproperty is equal to"United States".- That same

personvertex also has an outgoingLIVES_INedge. Following that edge, and then a chain of outgoingWITHINedges, you eventually reach a vertex of typeLocation, whosenameproperty is equal to"Europe".For each such

personvertex, return thenameproperty.

There are several possible ways of executing the query. The description given here suggests that you start by scanning all the people in the database, examine each person’s birthplace and residence, and return only those people who meet the criteria.

But equivalently, you could start with the two Location vertices and work backward. If there is an index on the name property, you can efficiently find the two vertices representing the US and Europe. Then you can proceed to find all locations (states, regions, cities, etc.) in the US and Europe respectively by following all incoming WITHIN edges. Finally, you can look for people who can be found through an incoming BORN_IN or LIVES_IN edge at one of the location vertices.

SQL中的图查询

Example 3-3 suggested that graph data can be represented in a relational database. But if we put graph data in a relational structure, can we also query it using SQL?

The answer is yes, but with some difficulty. Every edge that you traverse in a graph query is effectively a join with the edges table. In a relational database, you usually know in advance which joins you need in your query. On the other hand, in a graph query, you may need to traverse a variable number of edges before you find the vertex you’re looking for—that is, the number of joins is not fixed in advance.

In our example, that happens in the () -[:WITHIN*0..]-> () pattern in the Cypher query. A person’s LIVES_IN edge may point at any kind of location: a street, a city, a district, a region, a state, etc. A city may be WITHIN a region, a region WITHIN a state, a state WITHIN a country, etc. The LIVES_IN edge may point directly at the location vertex you’re looking for, or it may be several levels away in the location hierarchy.

In Cypher, :WITHIN*0.. expresses that fact very concisely: it means “follow a WITHIN edge, zero or more times.” It is like the * operator in a regular expression.

Since SQL:1999, this idea of variable-length traversal paths in a query can be expressed using something called recursive common table expressions (the WITH RECURSIVE syntax). Example 3-6 shows the same query—finding the names of people who emigrated from the US to Europe—expressed in SQL using this technique. However, the syntax is very clumsy in comparison to Cypher.

Example 3-6. The same query as Example 3-5, written in SQL using recursive common table expressions

WITH RECURSIVE

-- in_usa is the set of vertex IDs of all locations within the United States

in_usa(vertex_id) AS (

SELECT vertex_id FROM vertices

WHERE label = 'Location' AND properties->>'name' = 'United States'

UNION

SELECT edges.tail_vertex FROM edges

JOIN in_usa ON edges.head_vertex = in_usa.vertex_id

WHERE edges.label = 'within'

),

-- in_europe is the set of vertex IDs of all locations within Europe

in_europe(vertex_id) AS (

SELECT vertex_id FROM vertices

WHERE label = 'location' AND properties->>'name' = 'Europe'

UNION

SELECT edges.tail_vertex FROM edges

JOIN in_europe ON edges.head_vertex = in_europe.vertex_id

WHERE edges.label = 'within'

),

-- born_in_usa is the set of vertex IDs of all people born in the US

born_in_usa(vertex_id) AS (

SELECT edges.tail_vertex FROM edges

JOIN in_usa ON edges.head_vertex = in_usa.vertex_id

WHERE edges.label = 'born_in'

),

-- lives_in_europe is the set of vertex IDs of all people living in Europe

lives_in_europe(vertex_id) AS (

SELECT edges.tail_vertex FROM edges

JOIN in_europe ON edges.head_vertex = in_europe.vertex_id

WHERE edges.label = 'lives_in'

)

SELECT vertices.properties->>'name'

FROM vertices

-- join to find those people who were both born in the US *and* live in Europe

JOIN born_in_usa ON vertices.vertex_id = born_in_usa.vertex_id

JOIN lives_in_europe ON vertices.vertex_id = lives_in_europe.vertex_id;

-

First find the vertex whose

nameproperty has the value"United States", and make it the first element of the set of verticesin_usa. -

Follow all incoming

withinedges from vertices in the setin_usa, and add them to the same set, until all incomingwithinedges have been visited. -

Do the same starting with the vertex whose

nameproperty has the value"Europe", and build up the set of verticesin_europe. -

For each of the vertices in the set

in_usa, follow incomingborn_inedges to find people who were born in some place within the United States. -

Similarly, for each of the vertices in the set

in_europe, follow incominglives_inedges to find people who live in Europe. -

Finally, intersect the set of people born in the USA with the set of people living in Europe, by joining them.

The fact that a 4-line Cypher query requires 31 lines in SQL shows how much of a difference the right choice of data model and query language can make. And this is just the beginning; there are more details to consider, e.g., around handling cycles, and choosing between breadth-first or depth-first traversal [39]. Oracle has a different SQL extension for recursive queries, which it calls hierarchical [40].

However, the situation may be improving: at the time of writing, there are plans to add a graph query language called GQL to the SQL standard [41, 42], which will provide a syntax inspired by Cypher, GSQL [43], and PGQL [44].

三元组与SPARQL

The triple-store model is mostly equivalent to the property graph model, using different words to describe the same ideas. It is nevertheless worth discussing, because there are various tools and languages for triple-stores that can be valuable additions to your toolbox for building applications.

In a triple-store, all information is stored in the form of very simple three-part statements: (subject, predicate, object). For example, in the triple (Jim, likes, bananas), Jim is the subject, likes is the predicate (verb), and bananas is the object.

The subject of a triple is equivalent to a vertex in a graph. The object is one of two things:

- A value of a primitive datatype, such as a string or a number. In that case, the predicate and object of the triple are equivalent to the key and value of a property on the subject vertex. Using the example from Figure 3-6, (lucy, birthYear, 1989) is like a vertex

lucywith properties{"birthYear": 1989}. - Another vertex in the graph. In that case, the predicate is an edge in the graph, the subject is the tail vertex, and the object is the head vertex. For example, in (lucy, marriedTo, alain) the subject and object lucy and alain are both vertices, and the predicate marriedTo is the label of the edge that connects them.

注意

To be precise, databases that offer a triple-like data model often need to store some additional metadata on each tuple. For example, AWS Neptune uses quads (4-tuples) by adding a graph ID to each triple [45]; Datomic uses 5-tuples, extending each triple with a transaction ID and a boolean to indicate deletion [46]. Since these databases retain the basic subject-predicate-object structure explained above, this book nevertheless calls them triple-stores.

Example 3-7 shows the same data as in Example 3-4, written as triples in a format called Turtle, a subset of Notation3 (N3) [47].

Example 3-7. A subset of the data in Figure 3-6, represented as Turtle triples

@prefix : <urn:example:>.

_:lucy a :Person.

_:lucy :name "Lucy".

_:lucy :bornIn _:idaho.

_:idaho a :Location.

_:idaho :name "Idaho".

_:idaho :type "state".

_:idaho :within _:usa.

_:usa a :Location.

_:usa :name "United States".

_:usa :type "country".

_:usa :within _:namerica.

_:namerica a :Location.

_:namerica :name "North America".

_:namerica :type "continent".

In this example, vertices of the graph are written as _:*someName*. The name doesn’t mean anything outside of this file; it exists only because we otherwise wouldn’t know which triples refer to the same vertex. When the predicate represents an edge, the object is a vertex, as in _:idaho :within _:usa. When the predicate is a property, the object is a string literal, as in _:usa :name "United States".

It’s quite repetitive to repeat the same subject over and over again, but fortunately you can use semicolons to say multiple things about the same subject. This makes the Turtle format quite readable: see Example 3-8.

Example 3-8. A more concise way of writing the data in Example 3-7

@prefix : <urn:example:>.

_:lucy a :Person; :name "Lucy"; :bornIn _:idaho.

_:idaho a :Location; :name "Idaho"; :type "state"; :within _:usa.

_:usa a :Location; :name "United States"; :type "country"; :within _:namerica.

_:namerica a :Location; :name "North America"; :type "continent".

The Semantic Web

Some of the research and development effort on triple stores was motivated by the Semantic Web, an early-2000s effort to facilitate internet-wide data exchange by publishing data not only as human-readable web pages, but also in a standardized, machine-readable format. Although the Semantic Web as originally envisioned did not succeed [48, 49], the legacy of the Semantic Web project lives on in a couple of specific technologies: linked data standards such as JSON-LD [50], ontologies used in biomedical science [51], Facebook’s Open Graph protocol [52] (which is used for link unfurling [53]), knowledge graphs such as Wikidata, and standardized vocabularies for structured data maintained by schema.org.

Triple-stores are another Semantic Web technology that has found use outside of its original use case: even if you have no interest in the Semantic Web, triples can be a good internal data model for applications.

The RDF data model

The Turtle language we used in Example 3-8 is actually a way of encoding data in the Resource Description Framework (RDF) [54], a data model that was designed for the Semantic Web. RDF data can also be encoded in other ways, for example (more verbosely) in XML, as shown in Example 3-9. Tools like Apache Jena can automatically convert between different RDF encodings.

Example 3-9. The data of Example 3-8, expressed using RDF/XML syntax

<rdf:RDF xmlns="urn:example:"

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#">

<Location rdf:nodeID="idaho">

<name>Idaho</name>

<type>state</type>

<within>

<Location rdf:nodeID="usa">

<name>United States</name>

<type>country</type>

<within>

<Location rdf:nodeID="namerica">

<name>North America</name>

<type>continent</type>

</Location>

</within>

</Location>

</within>

</Location>

<Person rdf:nodeID="lucy">

<name>Lucy</name>

<bornIn rdf:nodeID="idaho"/>

</Person>

</rdf:RDF>

RDF has a few quirks due to the fact that it is designed for internet-wide data exchange. The subject, predicate, and object of a triple are often URIs. For example, a predicate might be an URI such as <http://my-company.com/namespace#within> or <http://my-company.com/namespace#lives_in>, rather than just WITHIN or LIVES_IN. The reasoning behind this design is that you should be able to combine your data with someone else’s data, and if they attach a different meaning to the word within or lives_in, you won’t get a conflict because their predicates are actually <http://other.org/foo#within> and <http://other.org/foo#lives_in>.

The URL <http://my-company.com/namespace> doesn’t necessarily need to resolve to anything—from RDF’s point of view, it is simply a namespace. To avoid potential confusion with http:// URLs, the examples in this section use non-resolvable URIs such as urn:example:within. Fortunately, you can just specify this prefix once at the top of the file, and then forget about it.

SPARQL查询语言

SPARQL is a query language for triple-stores using the RDF data model [55]. (It is an acronym for SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language, pronounced “sparkle.”) It predates Cypher, and since Cypher’s pattern matching is borrowed from SPARQL, they look quite similar.

The same query as before—finding people who have moved from the US to Europe—is similarly concise in SPARQL as it is in Cypher (see Example 3-10).

Example 3-10. The same query as Example 3-5, expressed in SPARQL

PREFIX : <urn:example:>

SELECT ?personName WHERE {

?person :name ?personName.

?person :bornIn / :within* / :name "United States".

?person :livesIn / :within* / :name "Europe".

}

The structure is very similar. The following two expressions are equivalent (variables start with a question mark in SPARQL):

(person) -[:BORN_IN]-> () -[:WITHIN*0..]-> (location) # Cypher

?person :bornIn / :within* ?location. # SPARQL

Because RDF doesn’t distinguish between properties and edges but just uses predicates for both, you can use the same syntax for matching properties. In the following expression, the variable usa is bound to any vertex that has a name property whose value is the string "United States":

(usa {name:'United States'}) # Cypher

?usa :name "United States". # SPARQL

SPARQL is supported by Amazon Neptune, AllegroGraph, Blazegraph, OpenLink Virtuoso, Apache Jena, and various other triple stores [35].

Datalog:递归关系查询

Datalog is a much older language than SPARQL or Cypher: it arose from academic research in the 1980s [56, 57, 58]. It is less well known among software engineers and not widely supported in mainstream databases, but it ought to be better-known since it is a very expressive language that is particularly powerful for complex queries. Several niche databases, including Datomic, LogicBlox, CozoDB, and LinkedIn’s LIquid [59] use Datalog as their query language.

Datalog is actually based on a relational data model, not a graph, but it appears in the graph databases section of this book because recursive queries on graphs are a particular strength of Datalog.

The contents of a Datalog database consists of facts, and each fact corresponds to a row in a relational table. For example, say we have a table location containing locations, and it has three columns: ID, name, and type. The fact that the US is a country could then be written as location(2, "United States", "country"), where 2 is the ID of the US. In general, the statement table(val1, val2, …) means that table contains a row where the first column contains val1, the second column contains val2, and so on.

Example 3-11 shows how to write the data from the left-hand side of Figure 3-6 in Datalog. The edges of the graph (within, born_in, and lives_in) are represented as two-column join tables. For example, Lucy has the ID 100 and Idaho has the ID 3, so the relationship “Lucy was born in Idaho” is represented as born_in(100, 3).

Example 3-11. A subset of the data in Figure 3-6, represented as Datalog facts

location(1, "North America", "continent").

location(2, "United States", "country").

location(3, "Idaho", "state").

within(2, 1). /* US is in North America */

within(3, 2). /* Idaho is in the US */

person(100, "Lucy").

born_in(100, 3). /* Lucy was born in Idaho */

Now that we have defined the data, we can write the same query as before, as shown in Example 3-12. It looks a bit different from the equivalent in Cypher or SPARQL, but don’t let that put you off. Datalog is a subset of Prolog, a programming language that you might have seen before if you’ve studied computer science.

Example 3-12. The same query as Example 3-5, expressed in Datalog

within_recursive(LocID, PlaceName) :- location(LocID, PlaceName, _). /* Rule 1 */

within_recursive(LocID, PlaceName) :- within(LocID, ViaID), /* Rule 2 */

within_recursive(ViaID, PlaceName).

migrated(PName, BornIn, LivingIn) :- person(PersonID, PName), /* Rule 3 */

born_in(PersonID, BornID),

within_recursive(BornID, BornIn),

lives_in(PersonID, LivingID),

within_recursive(LivingID, LivingIn).

us_to_europe(Person) :- migrated(Person, "United States", "Europe"). /* Rule 4 */

/* us_to_europe contains the row "Lucy". */

Cypher and SPARQL jump in right away with SELECT, but Datalog takes a small step at a time. We define rules that derive new virtual tables from the underlying facts. These derived tables are like (virtual) SQL views: they are not stored in the database, but you can query them in the same way as a table containing stored facts.

In Example 3-12 we define three derived tables: within_recursive, migrated, and us_to_europe. The name and columns of the virtual tables are defined by what appears before the :- symbol of each rule. For example, migrated(PName, BornIn, LivingIn) is a virtual table with three columns: the name of a person, the name of the place where they were born, and the name of the place where they are living.

The content of a virtual table is defined by the part of the rule after the :- symbol, where we try to find rows that match a certain pattern in the tables. For example, person(PersonID, PName) matches the row person(100, "Lucy"), with the variable PersonID bound to the value 100 and the variable PName bound to the value "Lucy". A rule applies if the system can find a match for all patterns on the righthand side of the :- operator. When the rule applies, it’s as though the lefthand side of the :- was added to the database (with variables replaced by the values they matched).

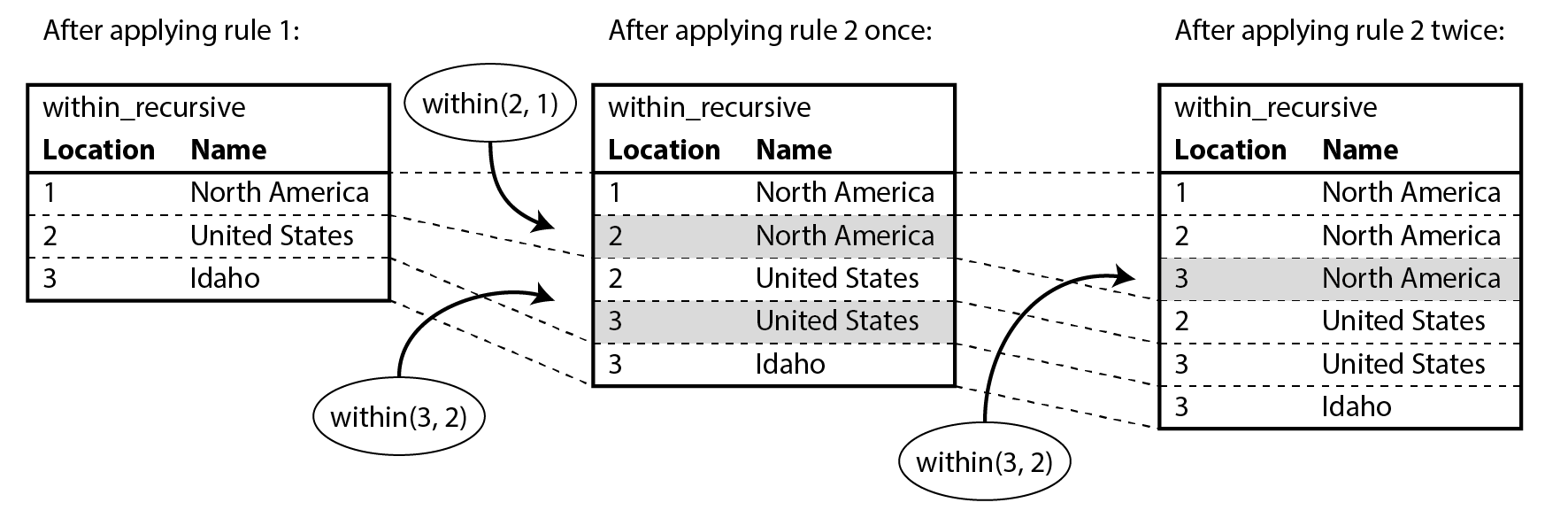

One possible way of applying the rules is thus (and as illustrated in Figure 3-7):

location(1, "North America", "continent")exists in the database, so rule 1 applies. It generateswithin_recursive(1, "North America").within(2, 1)exists in the database and the previous step generatedwithin_recursive(1, "North America"), so rule 2 applies. It generateswithin_recursive(2, "North America").within(3, 2)exists in the database and the previous step generatedwithin_recursive(2, "North America"), so rule 2 applies. It generateswithin_recursive(3, "North America").

By repeated application of rules 1 and 2, the within_recursive virtual table can tell us all the locations in North America (or any other location) contained in our database.

Figure 3-7. Determining that Idaho is in North America, using the Datalog rules from Example 3-12.

Now rule 3 can find people who were born in some location BornIn and live in some location LivingIn. Rule 4 invokes rule 3 with BornIn = 'United States' and LivingIn = 'Europe', and returns only the names of the people who match the search. By querying the contents of the virtual us_to_europe table, the Datalog system finally gets the same answer as in the earlier Cypher and SPARQL queries.

The Datalog approach requires a different kind of thinking compared to the other query languages discussed in this chapter. It allows complex queries to be built up rule by rule, with one rule referring to other rules, similarly to the way that you break down code into functions that call each other. Just like functions can be recursive, Datalog rules can also invoke themselves, like rule 2 in Example 3-12, which enables graph traversals in Datalog queries.

GraphQL

GraphQL is a query language that, by design, is much more restrictive than the other query languages we have seen in this chapter. The purpose of GraphQL is to allow client software running on a user’s device (such as a mobile app or a JavaScript web app frontend) to request a JSON document with a particular structure, containing the fields necessary for rendering its user interface. GraphQL interfaces allow developers to rapidly change queries in client code without changing server-side APIs.

GraphQL’s flexibility comes at a cost. Organizations that adopt GraphQL often need tooling to convert GraphQL queries into requests to internal services, which often use REST or gRPC (see [Link to Come]). Authorization, rate limiting, and performance challenges are additional concerns [60]. GraphQL’s query language is also limited since GraphQL come from an untrusted source. The language does not allow anything that could be expensive to execute, since otherwise users could perform denial-of-service attacks on a server by running lots of expensive queries. In particular, GraphQL does not allow recursive queries (unlike Cypher, SPARQL, SQL, or Datalog), and it does not allow arbitrary search conditions such as “find people who were born in the US and are now living in Europe” (unless the service owners specifically choose to offer such search functionality).

Nevertheless, GraphQL is useful. Example 3-13 shows how you might implement a group chat application such as Discord or Slack using GraphQL. The query requests all the channels that the user has access to, including the channel name and the 50 most recent messages in each channel. For each message it requests the timestamp, the message content, and the name and profile picture URL for the sender of the message. Moreover, if a message is a reply to another message, the query also requests the sender name and the content of the message it is replying to (which might be rendered in a smaller font above the reply, in order to provide some context).

Example 3-13. Example GraphQL query for a group chat application

query ChatApp {

channels {

name

recentMessages(latest: 50) {

timestamp

content

sender {

fullName

imageUrl

}

replyTo {

content

sender {

fullName

}

}

}

}

}

Example 3-14 shows what a response to the query in Example 3-13 might look like. The response is a JSON document that mirrors the structure of the query: it contains exactly those attributes that were requested, no more and no less. This approach has the advantage that the server does not need to know which attributes the client requires in order to render the user interface; instead, the client can simply request what it needs. For example, this query does not request a profile picture URL for the sender of the replyTo message, but if the user interface were changed to add that profile picture, it would be easy for the client to add the required imageUrl attribute to the query without changing the server.

Example 3-14. A possible response to the query in Example 3-13

{

"data": {

"channels": [

{

"name": "#general",

"recentMessages": [

{

"timestamp": 1693143014,

"content": "Hey! How are y'all doing?",

"sender": {"fullName": "Aaliyah", "imageUrl": "https://..."},

"replyTo": null

},

{

"timestamp": 1693143024,

"content": "Great! And you?",

"sender": {"fullName": "Caleb", "imageUrl": "https://..."},

"replyTo": {

"content": "Hey! How are y'all doing?",

"sender": {"fullName": "Aaliyah"}

}

},

...

In Example 3-14 the name and image URL of a message sender is embedded directly in the message object. If the same user sends multiple messages, this information is repeated on each message. In principle, it would be possible to reduce this duplication, but GraphQL makes the design choice to accept a larger response size in order to make it simpler to render the user interface based on the data.

The replyTo field is similar: in Example 3-14, the second message is a reply to the first, and the content (“Hey!…”) and sender Aaliyah are duplicated under replyTo. It would be possible to instead return the ID of the message being replied to, but then the client would have to make an additional request to the server if that ID is not among the 50 most recent messages returned. Duplicating the content makes it much simpler to work with the data.

The server’s database can store the data in a more normalized form, and perform the necessary joins to process a query. For example, the server might store a message along with the user ID of the sender and the ID of the message it is replying to; when it receives a query like the one above, the server would then resolve those IDs to find the records they refer to. However, the client can only ask the server to perform joins that are explicitly offered in the GraphQL schema.

Even though the response to a GraphQL query looks similar to a response from a document database, and even though it has “graph” in the name, GraphQL can be implemented on top of any type of database—relational, document, or graph.

事件溯源与CQRS

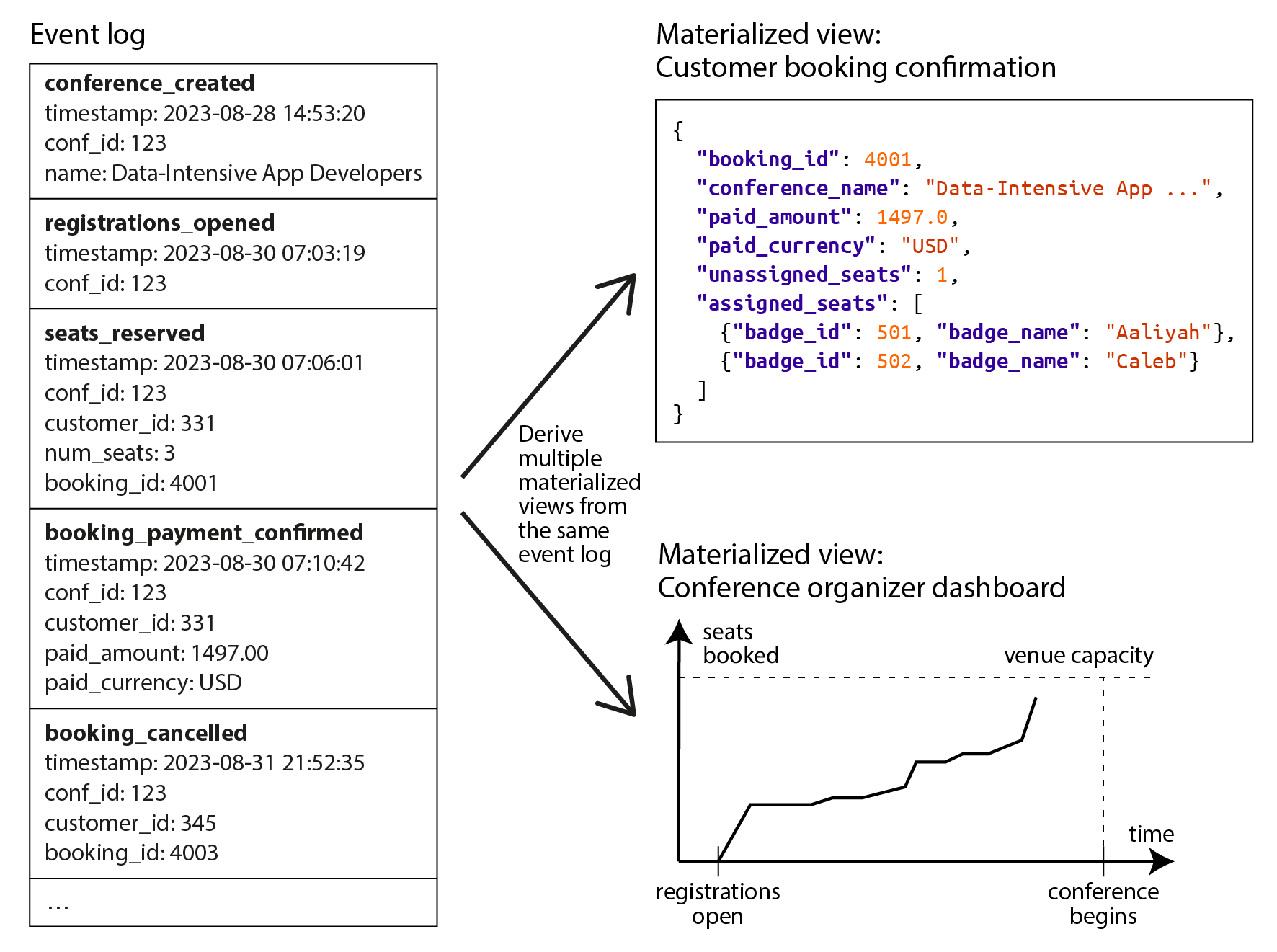

In all the data models we have discussed so far, the data is queried in the same form as it is written—be it JSON documents, rows in tables, or vertices and edges in a graph. However, in complex applications it can sometimes be difficult to find a single data representation that is able to satisfy all the different ways that the data needs to be queried and presented. In such situations, it can be beneficial to write data in one form, and then to derive from it several representations that are optimized for different types of reads.