@chensanle @amwps290 @MZqk @mengxinayan @scvoet @Tracygcz @MjSeven @RiaXu 请注意,申请文件已经超期回收。如果您还在此篇文章上工作,请重新申请并完成。

8.1 KiB

Review of Container-to-Container Communications in Kubernetes

This article was originally posted at TheNewStack.

By Matt Zand and Jim Sullivan

Kubernetes is a containerized solution. It provides virtualized runtime environments called Pods, which house one or more containers to provide a virtual runtime environment. An important aspect of Kubernetes is container communication within the Pod. Additionally, an important area of managing the Kubernetes network is to forward container ports internally and externally to make sure containers within a Pod communicate with one another properly. To manage such communications, Kubernetes offers the following four networking models:

- Container-to-Container communications

- Pod-to-Pod communications

- Pod-to-Service communications

- External-to-Internal communications

In this article, we dive into Container-to-Container communications, by showing you ways in which containers within a pod can network and communicate.

Communication Between Containers in a Pod

Having multiple containers in a single Pod makes it relatively straightforward for them to communicate with each other. They can do this using several different methods. In this article, we discuss two methods: i- Shared Volumes and ii-Inter-Process Communications in more detail.

I- Shared Volumes in a Kubernetes Pod

In Kubernetes, you can use a shared Kubernetes Volume as a simple and efficient way to share data between containers in a Pod. For most cases, it is sufficient to use a directory on the host that is shared with all containers within a Pod.

Kubernetes Volumes enables data to survive container restarts, but these volumes have the same lifetime as the Pod. This means that the volume (and the data it holds) exists exactly as long as that Pod exists. If that Pod is deleted for any reason, even if an identical replacement is created, the shared Volume is also destroyed and created from scratch.

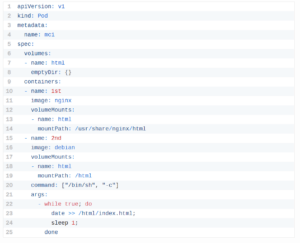

A standard use case for a multicontainer Pod with a shared Volume is when one container writes logs or other files to the shared directory, and the other container reads from the shared directory. For example, we can create a Pod like so:

In this example, we define a volume named html. Its type is emptyDir, which means that the Volume is first created when a Pod is assigned to a node and exists as long as that Pod is running on that node; as the name says, it is initially empty. The first container runs the Nginx server and has the shared Volume mounted to the directory /usr/share/nginx/html. The second container uses the Debian image and has the shared Volume mounted to the directory /html. Every second, the second container adds the current date and time into the index.html file, which is located in the shared Volume. When the user makes an HTTP request to the Pod, the Nginx server reads this file and transfers it back to the user in response to the request. Here is a good article for reading more on similar Kubernetes topics.

https://cdn.thenewstack.io/media/2020/11/d5362cd2-image1.png

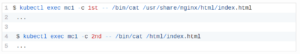

You can check that the pod is working either by exposing the nginx port and accessing it using your browser, or by checking the shared directory directly in the containers:

II- Inter-Process Communications (IPC)

Containers in a Pod share the same IPC namespace, which means they can also communicate with each other using standard inter-process communications such as SystemV semaphores or POSIX shared memory. Containers use the strategy of the localhost hostname for communication within a pod.

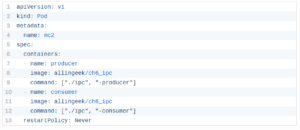

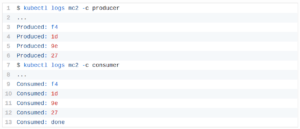

In the following example, we define a Pod with two containers. We use the same Docker image for both. The first container is a producer that creates a standard Linux message queue, writes a number of random messages, and then writes a special exit message. The second container is a consumer which opens that same message queue for reading and reads messages until it receives the exit message. We also set the restart policy to “Never”, so the Pod stops after the termination of both containers.

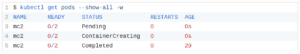

To check this out, create the pod using kubectl create and watch the Pod status:

Now you can check logs for each container and verify that the second container received all messages from the first container, including the exit message:

https://cdn.thenewstack.io/media/2020/11/6517d90b-image2.png

There is one major problem with this Pod, however, and it has to do with how containers start up.

Conclusion

The primary reason that Pods can have multiple containers is to support helper applications that assist a primary application. Typical examples of helper applications are data pullers, data pushers and proxies. An example of this pattern is a web server with a helper program that polls a git repository for new updates.

The Volume in this exercise provides a way for containers to communicate during the life of the Pod. If the Pod is deleted and recreated, any data stored in the shared Volume is lost. In this article, we also discussed the concept of Inter-Process Communications among containers within a Pod, which is an alternative to shared Volume concepts. Now that you learn how containers inside a Pod can communicate and exchange data, you can move on to learn other Kubernetes networking models — such as Pod-to-Pod or Pod-to-Service communications. Here is a good article for learning more advanced topics on Kubernetes development.

About the Authors

Matt Zand

Matt is is a serial entrepreneur and the founder of three successful tech startups: DC Web Makers, Coding Bootcamps and High School Technology Services. He is a leading author of Hands-on Smart Contract Development with Hyperledger Fabric book by O’Reilly Media.

Jim Sullivan

Jim has a bachelor’s degree in Electrical Engineering and a Master’s Degree in Computer Science. Jim also holds an MBA. Jim has been a practicing software engineer for 18 years. Currently, Jim leads an expert team in Blockchain development, DevOps, Cloud, application development, and the SAFe Agile methodology. Jim is an IBM Master Instructor.

The post Review of Container-to-Container Communications in Kubernetes appeared first on Linux Foundation – Training.

via: https://www.linux.com/news/review-of-container-to-container-communications-in-kubernetes/

作者:LF Training 选题:lujun9972 译者:译者ID 校对:校对者ID