18 KiB

12 cool things you can do with GitHub

I can’t for the life of me think of an intro, so…

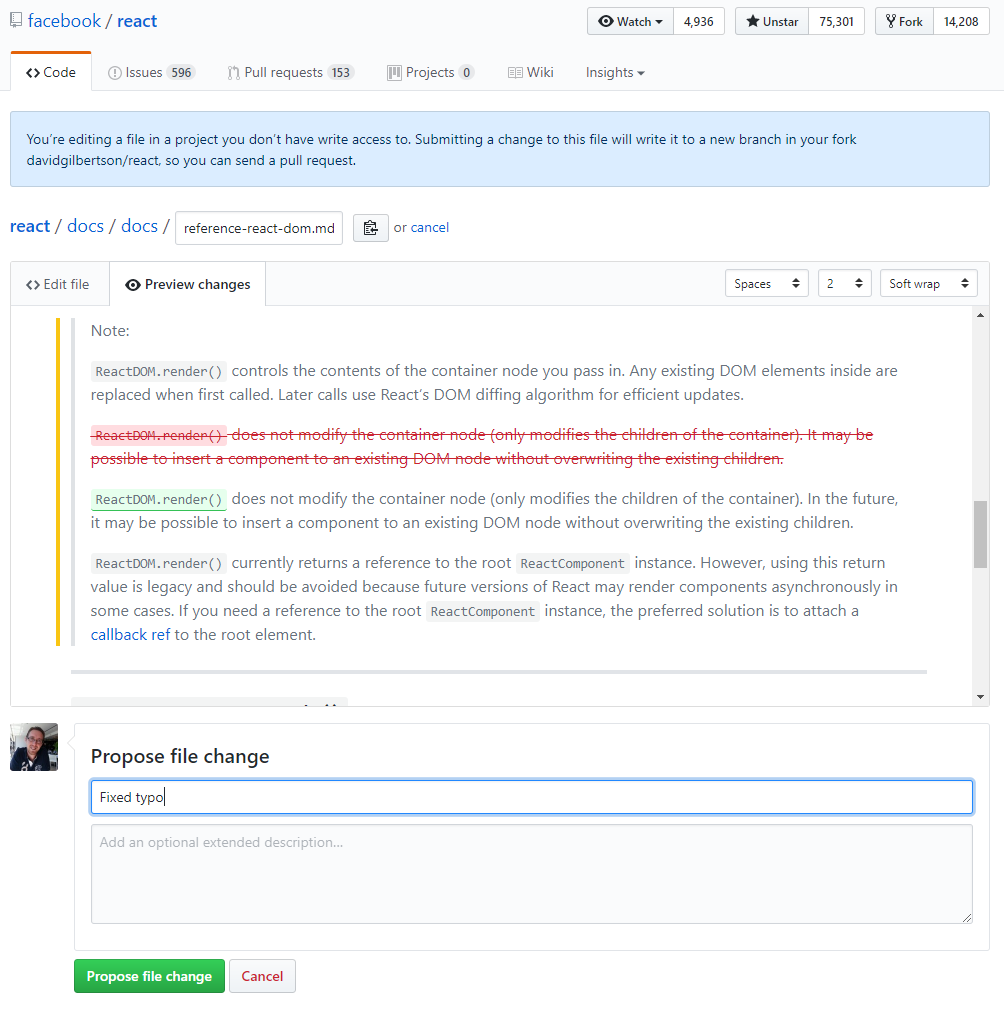

#1 Edit code on GitHub.com

I’m going to start with one that I think most people know (even though I didn’t know until a week ago).

When you’re in GitHub, looking at a file (any text file, any repository), there’s a little pencil up in the top right. If you click it, you can edit the file. When you’re done, hit Propose file change and GitHub will fork the repo for you and create a pull request.

Isn’t that wild? It creates the fork for you!

No need to fork and pull and change locally and push and create a PR.

This is great for fixing typos and a somewhat terrible idea for editing code.

#2 Pasting images

You’re not just limited to text in comments and issue descriptions. Did you know you can paste an image straight from the clipboard? When you paste, you’ll see it gets uploaded (to the ‘cloud’, no doubt) and becomes the markdown for showing an image.

Neat.

#3 Formatting code

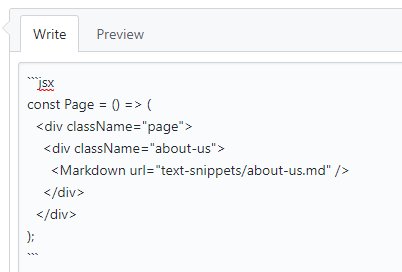

If you want to write a code block, you can start with three backticks — just like you learned when you read the Mastering Markdown page — and GitHub will make an attempt to guess what language you’re writing.

But if you’re posting a snippet of something like Vue, Typescript or JSX, you can specify that explicitly to get the right highlighting.

Note the ````jsx` on the first line here:

…which means the snippet is rendered correctly:

(This extends to gists, by the way. If you give a gist the extension of .jsxyou’ll get JSX syntax highlighting.)

Here’s a list of all the supported syntaxes.

#4 Closing issues with magic words in PRs

Let’s say you’re creating a pull request that fixes issue #234. You can put the text “fixes #234” in the description of your PR (or indeed anywhere in any comment on the PR).

Then, merging the PR automagically closes that issue. Isn’t that cool?

There’s more to learn in the help.

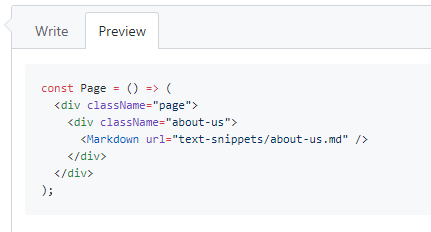

#5 Linking to comments

Have you even wanted to link to a particular comment but couldn’t work out how? That’s because you don’t know how to do it. But those days are behind you my friend, because I am here to tell you that clicking on the date/time next to the name is how you link to a comment.

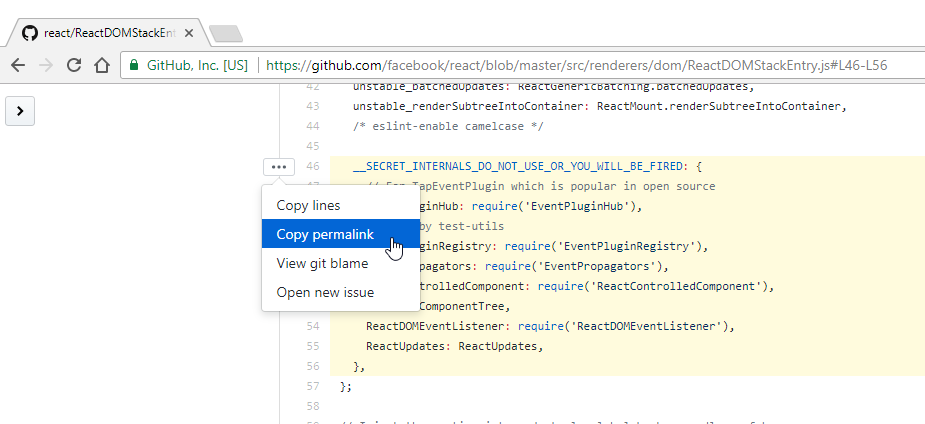

#6 Linking to code

So you want to link to a specific line of code. I get that.

Try this: while looking at the file, click the line number next to said code.

Whoa, did you see that? The URL was updated with the line number! If you hold down shift and click another line number, SHAZAAM, the URL is updated again and now you’ve highlighted a range of lines.

Sharing that URL will link to this file and those lines. But hold on, that’s pointing to the current branch. What if the file changes? Perhaps a permalink to the file in its current state is what you’re after.

I’m lazy so I’ve done all of the above in one screenshot:

Speaking of URLs…

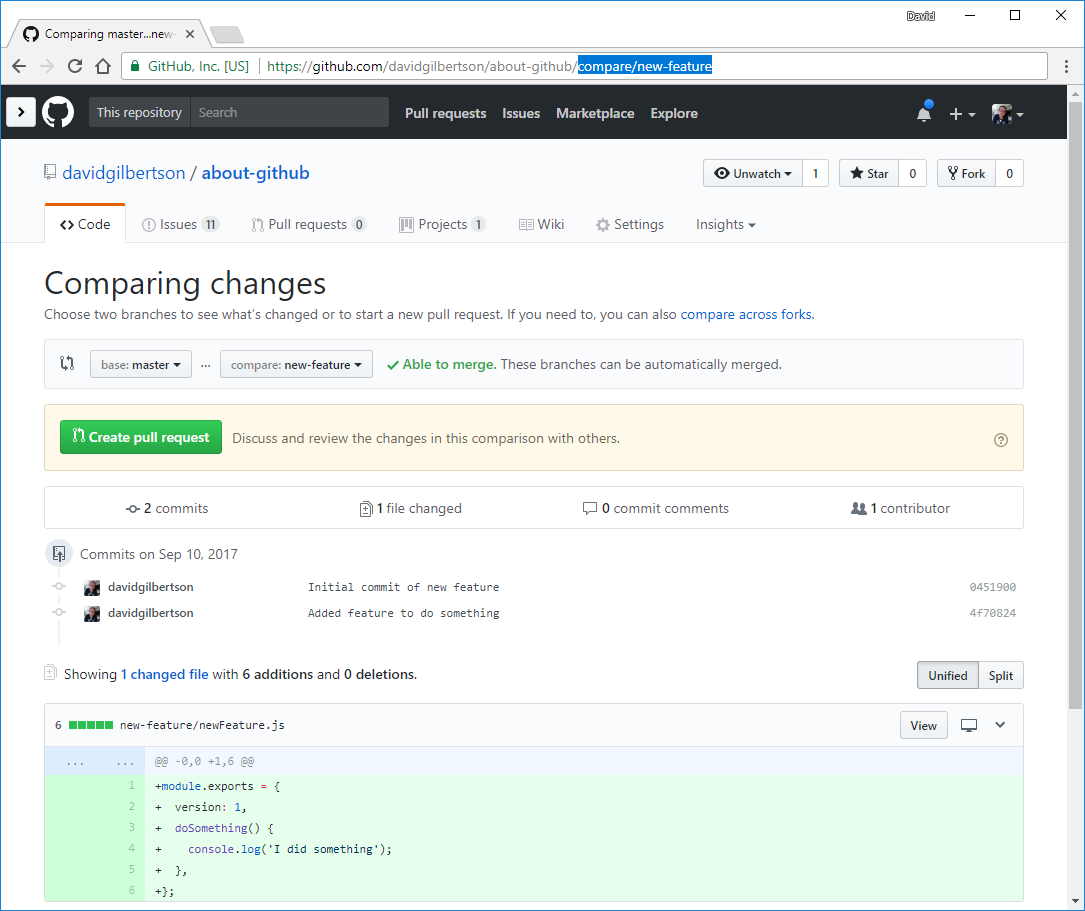

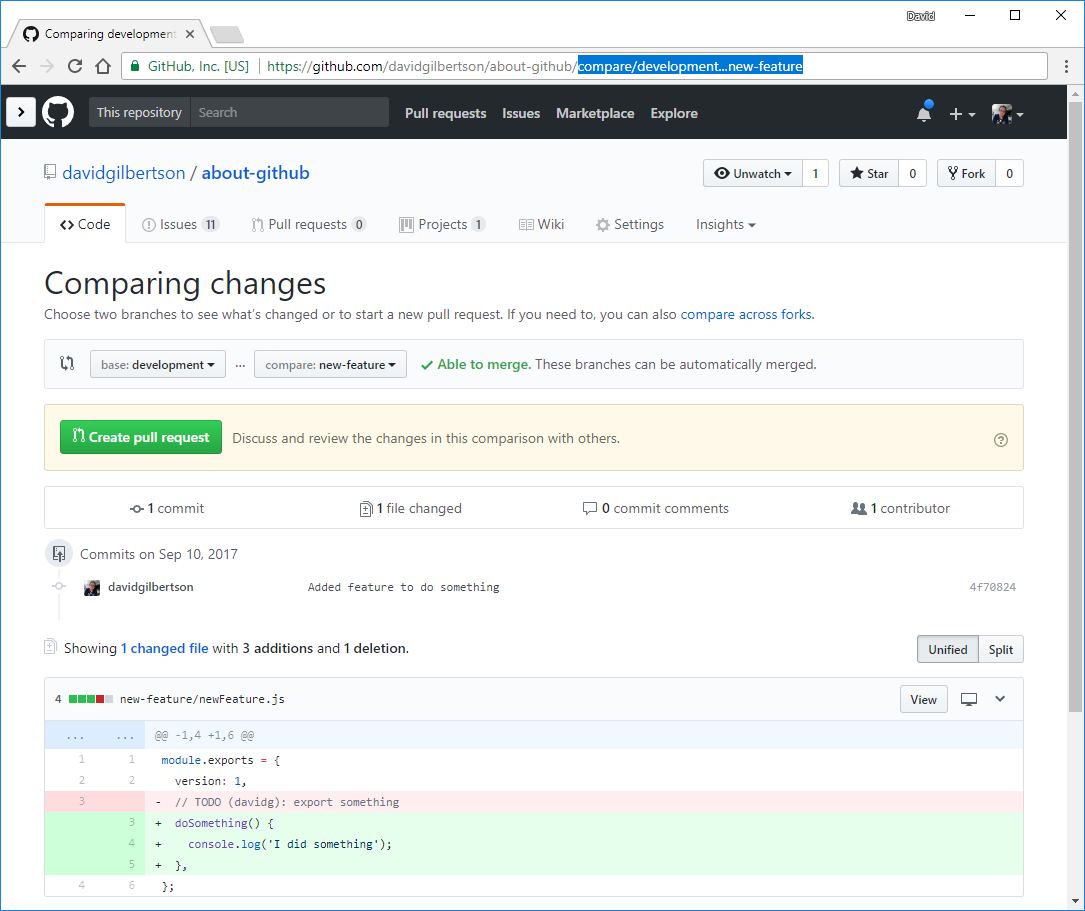

#7 Using the GitHub URL like the command line

Navigating around GitHub using the UI is all well and fine. But sometimes the fastest way to get where you want to be is just to type it in the URL. For example, if I want to jump to a branch that I’m working on and see the diff with master, I can type /compare/branch-name after my repo name.

That will land me on the diff page for that branch:

That’s a diff with master though, if I was working off an integration branch, I’d type /compare/integration-branch...my-branch

For you keyboard short-cutters out there, ctrl+L or cmd+L will jump the cursor up into the URL (in Chrome at least). This — coupled with the fact that your browser is going to do auto-complete — can make it a handy way to jump around between branches.

Pro-tip: use the arrow keys to move through Chrome’s auto-complete suggestions and hit shift+delete to remove an item from history (e.g. once a branch is merged).

(I really wonder if those shortcuts would be easier to read if I did them like shift + delete. But technically the ‘+’ isn’t part of it, so I don’t feel comfortable with that. This is what keeps me up at night, Rhonda.)

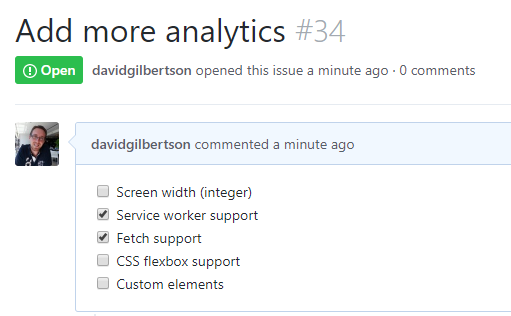

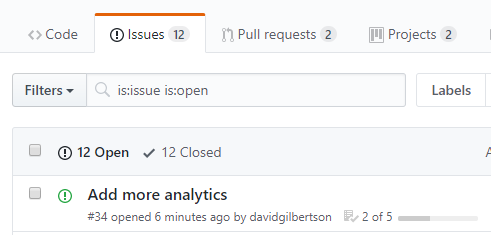

#8 Create lists, in issues

Do you want to see a list of check boxes in your issue?

And would you like that to show up as a nifty “2 of 5” bar when looking at the issue in a list?

That’s great! You can create interactive check boxes with this syntax:

- [ ] Screen width (integer)

- [x] Service worker support

- [x] Fetch support

- [ ] CSS flexbox support

- [ ] Custom elements

That’s a space and a dash and a space and a left bracket and a space (or an x) and a close bracket and a space and then some words.

Then you can actually check/uncheck those boxes! For some reason this seems like technical wizardry to me. You can check the boxes! And it updates the underlying text!

What will they think of next.

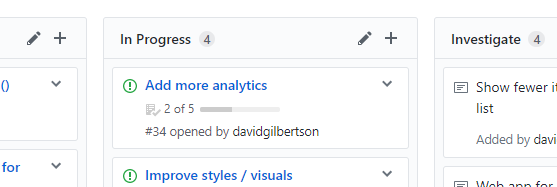

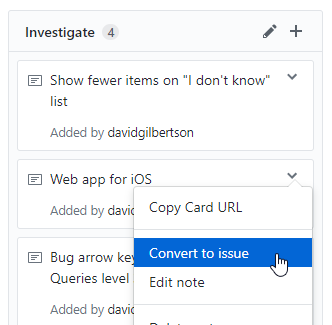

Oh and if you have this issue on a project board, it will show the progress there too:

If you don’t know what I’m talking about when I say “on a project board” then you’re in for a treat further down the page.

Like, 2cm further down the page.

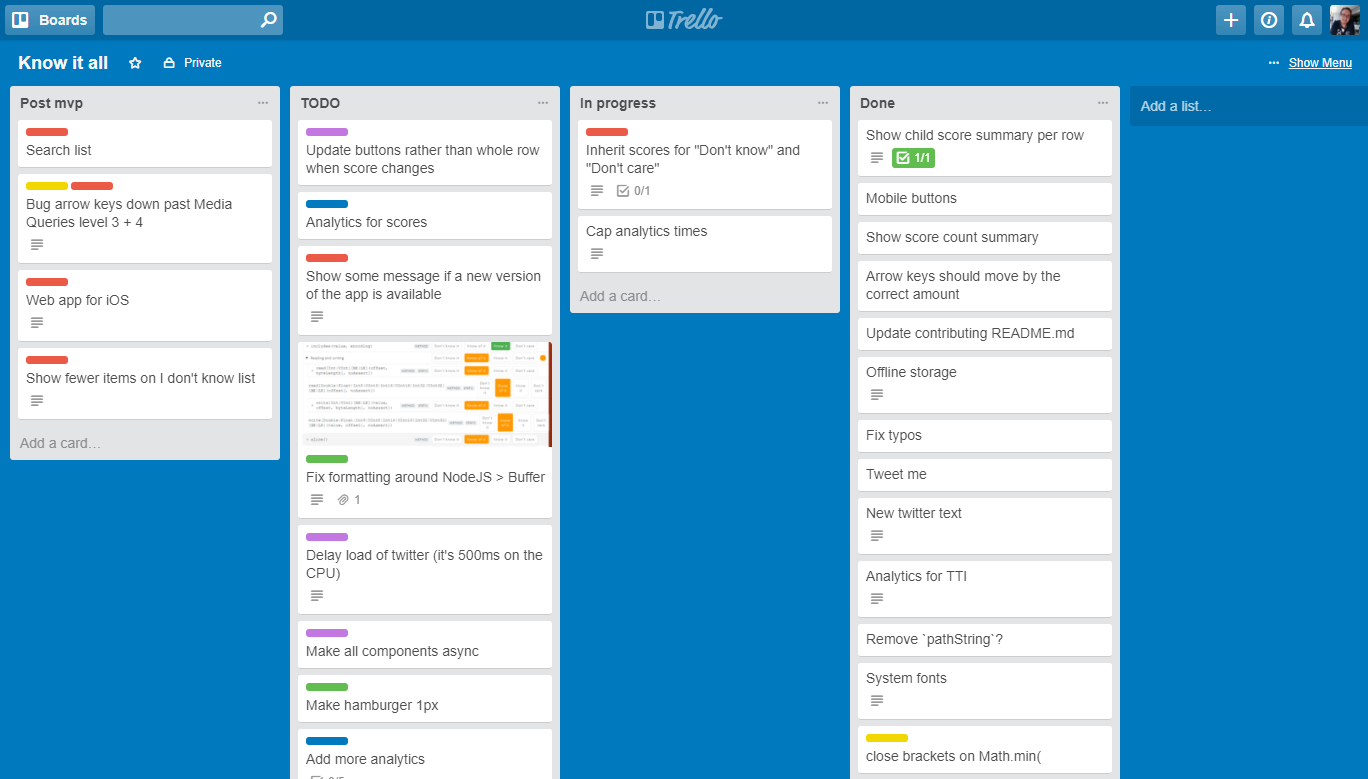

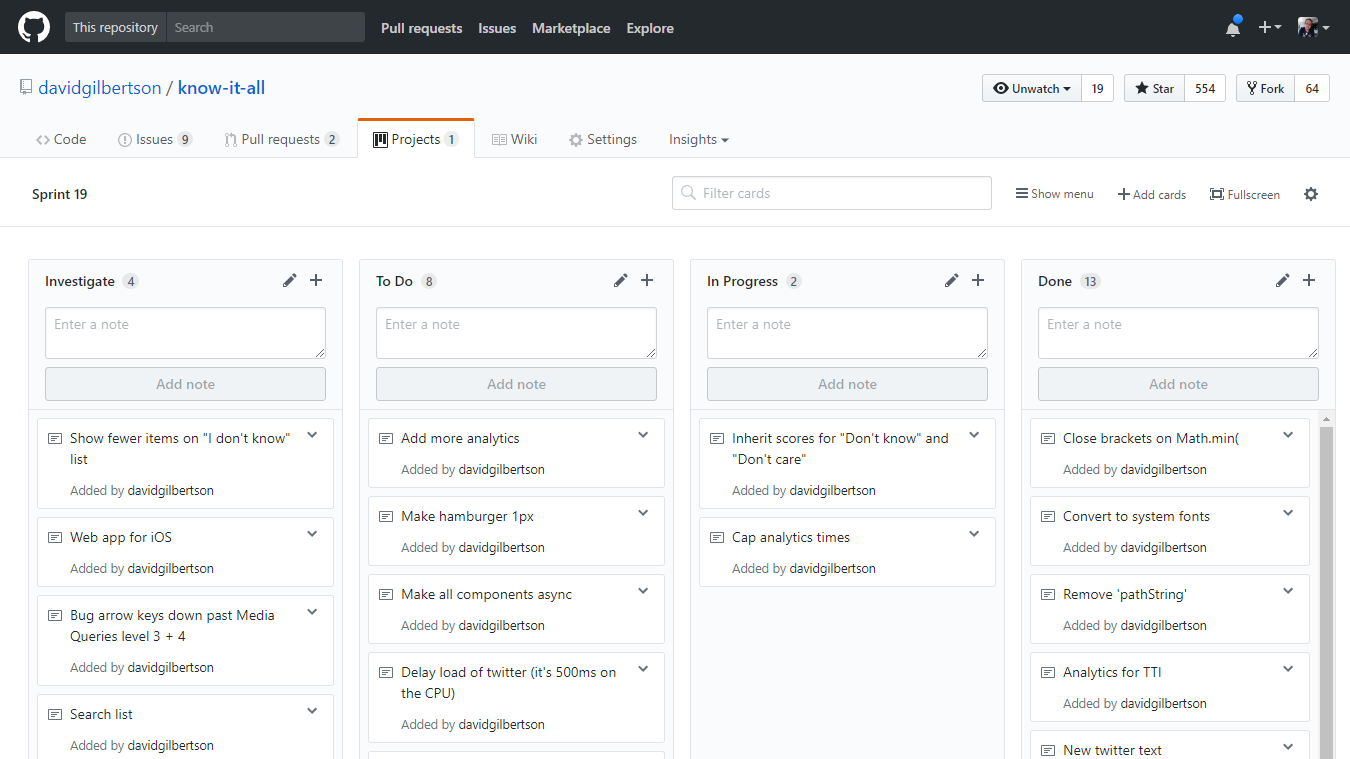

#9 Project boards in GitHub

I’ve always used Jira for big projects. And for solo projects I’ve always used Trello. I quite like both of them.

When I learned a few weeks back that GitHub has its own offering, right there on the Projects tab of my repo, I thought I’d replicate a set of tasks that I already had on the boil in Trello.

And here’s the same in a GitHub project:

Your eyes adjust to the lack of contrast eventually

Your eyes adjust to the lack of contrast eventually

For the sake of speed I added all of the above as ‘notes’ — which means they’re not actual GitHub issues.

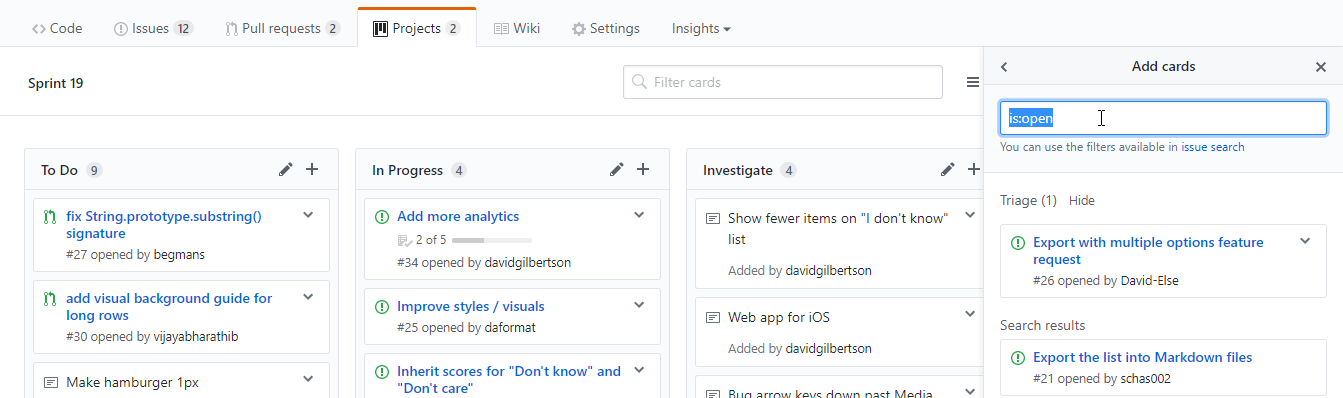

But the power of managing your tasks in GitHub is that it’s integrated with the rest of the repository — so you’ll probably want to add existing issues from the repo to the board.

You can click Add Cards up in the top right and find the things you want to add. Here the special search syntax comes in handy, for example, type is:pr is:open and now you can drag any open PRs onto the board, or label:bug if you want to smash some bugs.

Or you can convert existing notes to issues.

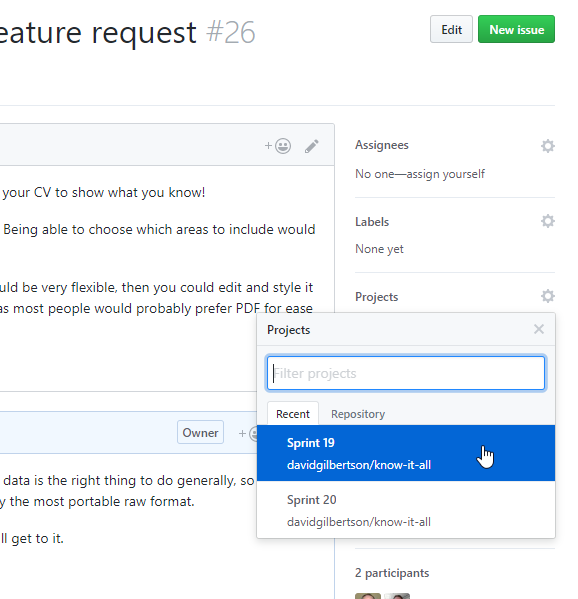

Or lastly, from an existing issue’s screen, add it to a project in the right pane.

It will go into a triage list on that project board so you can decide which column to put it in.

It will go into a triage list on that project board so you can decide which column to put it in.

There’s a huge (huuuuge) benefit in having your ‘task’ definition in the same repo as the code that implements that task. It means that years from now you can do a git blame on a line of code and find your way back to the original rationale behind the task that resulted in that code, without needing to go and track it down in Jira/Trello/elsewhere.

The downsides

I’ve been trialling doing all tasks in GitHub instead of Jira for the last three weeks (on a smaller project that is kinda-sorta Kanban style) and I’m liking it so far.

But I can’t imagine using it on scrum project where I want to do proper estimating and calculate velocity and all that good stuff.

The good news is, there are so few ‘features’ of GitHub Projects that it won’t take you long to assess if it’s something you could switch to. So give it a crack, see what you think.

FWIW, I have heard of ZenHub and opened it up 10 minutes ago for the first time ever. It effectively extends GitHub so you can estimate your issues and create epics and dependencies. There’s velocity and burndown charts too; it looks like it might just be the greatest thing on earth.

Further reading: GitHub help on Projects.

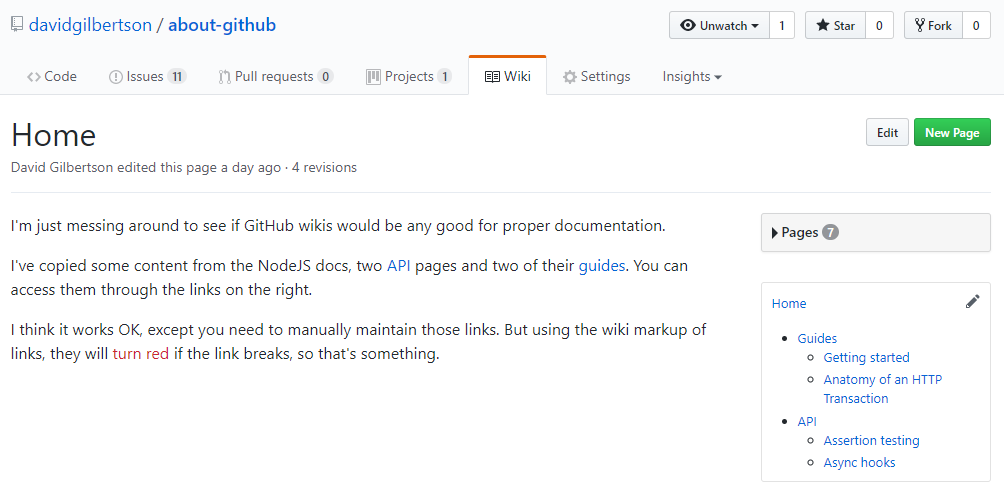

#10 GitHub wiki

For an unstructured collection of pages — just like Wikipedia — the GitHub Wiki offering (which I will henceforth refer to as Gwiki) is great.

For a structured collection of pages — for example, your documentation — not so much. There is no way to say “this page is a child of that page”, or have nice things like ‘Next section’ and ‘Previous section’ buttons. And Hansel and Gretel would be screwed, because there’s no breadcrumbs.

(Side note, have you read that story? It’s brutal. The two jerk kids murder the poor hungry old woman by burning her to death in her own oven . No doubt leaving her to clean up the mess. I think this is why youths these days are so darn sensitive — bedtime stories nowadays don’t contain enough violence.)

Moving on — to take Gwiki for a spin, I entered a few pages from the NodeJS docs as wiki pages, then created a custom sidebar so that I could emulate having some actual structure. The sidebar is there at all times, although it doesn’t highlight the page you are currently on.

Links have to be manually maintained, but over all, I think it would work just fine. Take a look if you feel the need.

It’s not going to compete with something like GitBook (that’s what the Redux docs use) or a bespoke website. But it’s a solid 80% and it’s all right there in your repo.

I’m a fan.

My suggestion: if you’ve outgrown a single README.md file and want a few different pages for user guides or more detailed documentation, then your next stop should be a Gwiki.

If you start to feel the lack of structure/navigation is holding you back, move on to something else.

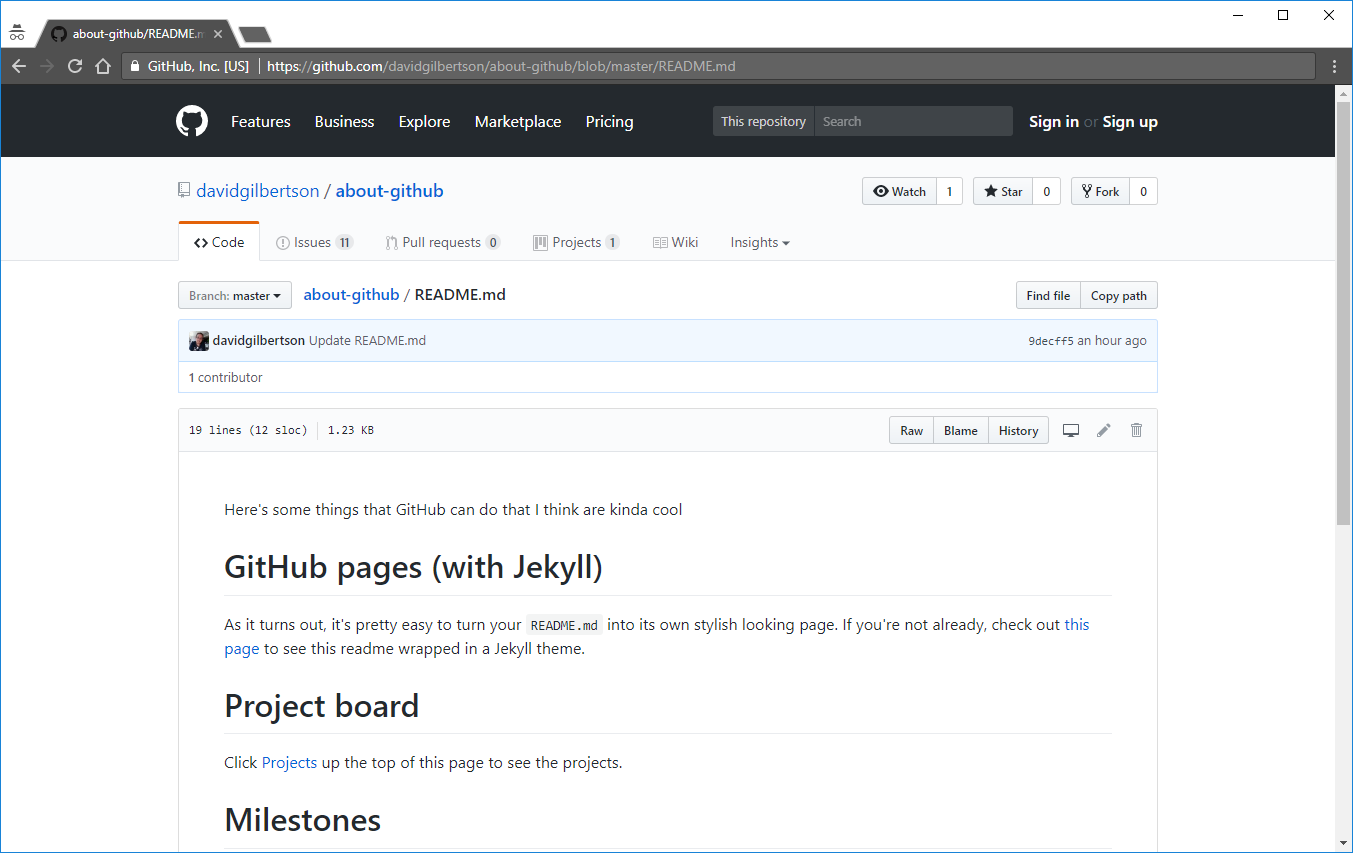

#11 GitHub Pages (with Jekyll)

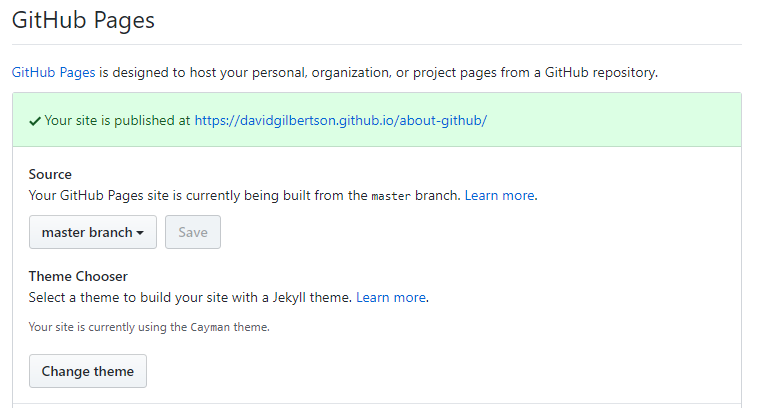

You may already know that you can use GitHub Pages to host a static site. And if you didn’t now you do. However this section is specifically about using Jekyll to build out a site.

At its very simplest, GitHub Pages + Jekyll will render your README.md in a pretty theme. For example, take a look at my readme page from about-github:

If I click the ‘settings’ tab for my site in GitHub, turn on GitHub Pages, and pick a Jekyll theme…

I will get a Jekyll-themed page:

From this point on I can build out a whole static site based mostly around markdown files that are easily editable, essentially turning GitHub into a CMS.

I haven’t actually used it, but this is how the React and Bootstrap sites are made, so it can’t be terrible.

Note, it requires Ruby to run locally (Windows users will exchange knowing glances and walk in the other direction. macOS users will be like “What’s the problem, where are you going? Ruby is a universal platform! GEMS!”)

(It’s also worth adding here that “Violent or threatening content or activity” is not allowed on GitHub Pages, so you can’t go hosting your Hansel and Gretel reboot.)

My opinion

The more I looked into GitHub Pages + Jekyll (for this post), the more it seemed like there was something a bit strange about the whole thing.

The idea of ‘taking all the complexity out of having your own web site’ is great. But you still need a build setup to work on it locally. And there’s an awful lot of CLI commands for something so ‘simple’.

I just skimmed over the seven pages in the Getting Started section, and I feel like I’m the only simple thing around here. And I haven’t even learnt the simple “Front Matter” syntax or the ins and outs of the simple “Liquid templating engine” yet.

I’d rather just write a website.

To be honest I’m a bit surprised Facebook use this for the React docs when they could probably build their help docs with React and pre-render to static HTML files in under a day.

All they would need is some way to consume their existing markdown files as though they were coming from a CMS.

I wonder if…

#12 Using GitHub as a CMS

Let’s say you have a website with some text in it, but you don’t want to store that text in the actual HTML markup.

Instead, you want to store chunks of text somewhere so they can easily be edited by non-developers. Perhaps with some form of version control. Maybe even a review process.

Here’s my suggestion: use markdown files stored in your repository to hold the text. Then have a component in your front end that fetches those chunks of text and renders them on the page.

I’m a React guy, so here’s an example of a <Markdown> component that, given the path to some markdown, will fetch, parse and render it as HTML.

(I’m using the marked npm package to parse the markdown into HTML.)

That’s pointing to my example repo that has some markdown files in [/text-snippets][2].

(You could also use the GiHub API to get the contents — but I’m not sure why you would.)

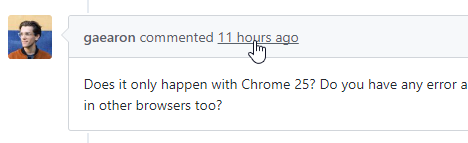

You would use such a component like so:

So now GitHub is your CMS, sort of, for whatever chunks of text you want it to house.

The above example only fetches the markdown after the component has mounted in the browser. If you want a static site then you’ll want to server-render this.

Good news! There’s nothing stopping you from fetching all the markdown files on the server (coupled with whatever caching strategy works for you). If you go down that road you might want to look at the GitHub API to get a list of all the markdown files in a directory.

Bonus round — GitHub tools!

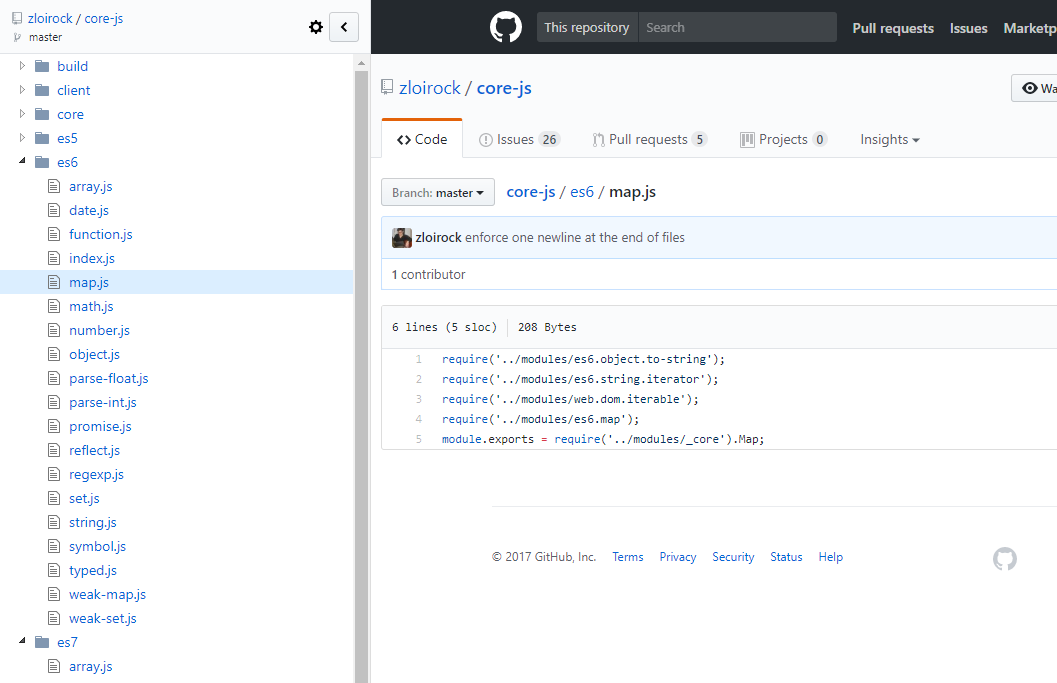

I’ve used the Octotree Chrome extension for a while now and I recommend it. Not wholeheartedly, but I recommend it nonetheless.

It gives you a panel over on the left with a tree view of whatever repo you’re looking at.

From this video I learned about octobox, which so far seems pretty good. It’s an inbox for your GitHub issues. That’s all I have to say about that.

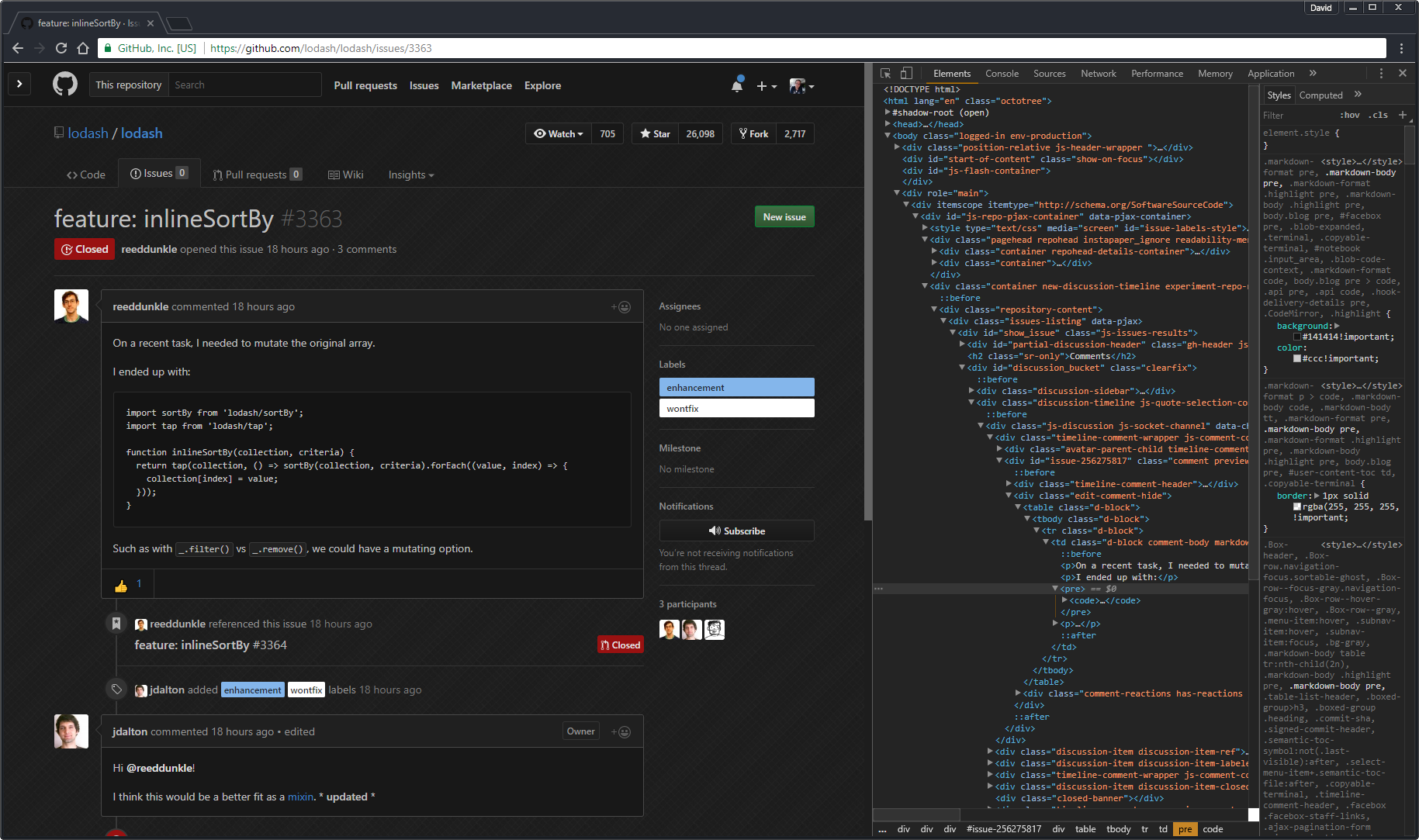

Speaking of colors, I’ve taken all my screenshots above in the light theme so as not to startle you. But really, everything else I look at is dark themed, why must I endure a pallid GitHub?

That’s a combo of the Stylish Chrome extension (which can apply themes to any website) and the GitHub Dark style. And to complete the look, the dark theme of Chrome DevTools (which is built in, turn it on in settings) and the Atom One Dark Theme for Chrome.

Bitbucket

This doesn’t strictly fit anywhere in this post, but it wouldn’t be right if I didn’t give a shout-out to Bitbucket.

Two years ago I was starting a project and spent half a day assessing which git host was best, and Bitbucket won by a considerable margin. Their code review flow was just so far ahead (this was long before GitHub even had the concept of assigning a reviewer).

GitHub has since caught up in the review game, which is great. But sadly I haven’t had the chance to use Bitbucket in the last year — perhaps they’ve bounded ahead in some other way. So, I would urge anyone in the position of choosing a git host to check out Bitbucket too.

Outro

So that’s it! I hope there were at least three things in here that you didn’t know already, and also I hope that you have a nice day.

Edit: there’s more tips in the comments; feel free to leave your own favourite. And seriously, I really do hope you have a nice day.

via: https://hackernoon.com/12-cool-things-you-can-do-with-github-f3e0424cf2f0

作者:David Gilbertson 译者:译者ID 校对:校对者ID