mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-01-16 22:42:21 +08:00

259 lines

14 KiB

Markdown

259 lines

14 KiB

Markdown

translating by Flowsnow

|

||

|

||

Build a bikesharing app with Redis and Python

|

||

======

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

I travel a lot on business. I'm not much of a car guy, so when I have some free time, I prefer to walk or bike around a city. Many of the cities I've visited on business have bikeshare systems, which let you rent a bike for a few hours. Most of these systems have an app to help users locate and rent their bikes, but it would be more helpful for users like me to have a single place to get information on all the bikes in a city that are available to rent.

|

||

|

||

To solve this problem and demonstrate the power of open source to add location-aware features to a web application, I combined publicly available bikeshare data, the [Python][1] programming language, and the open source [Redis][2] in-memory data structure server to index and query geospatial data.

|

||

|

||

The resulting bikeshare application incorporates data from many different sharing systems, including the [Citi Bike][3] bikeshare in New York City. It takes advantage of the General Bikeshare Feed provided by the Citi Bike system and uses its data to demonstrate some of the features that can be built using Redis to index geospatial data. The Citi Bike data is provided under the [Citi Bike data license agreement][4].

|

||

|

||

### General Bikeshare Feed Specification

|

||

|

||

The General Bikeshare Feed Specification (GBFS) is an [open data specification][5] developed by the [North American Bikeshare Association][6] to make it easier for map and transportation applications to add bikeshare systems into their platforms. The specification is currently in use by over 60 different sharing systems in the world.

|

||

|

||

The feed consists of several simple [JSON][7] data files containing information about the state of the system. The feed starts with a top-level JSON file referencing the URLs of the sub-feed data:

|

||

```

|

||

{

|

||

|

||

"data": {

|

||

|

||

"en": {

|

||

|

||

"feeds": [

|

||

|

||

{

|

||

|

||

"name": "system_information",

|

||

|

||

"url": "https://gbfs.citibikenyc.com/gbfs/en/system_information.json"

|

||

|

||

},

|

||

|

||

{

|

||

|

||

"name": "station_information",

|

||

|

||

"url": "https://gbfs.citibikenyc.com/gbfs/en/station_information.json"

|

||

|

||

},

|

||

|

||

. . .

|

||

|

||

]

|

||

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

},

|

||

|

||

"last_updated": 1506370010,

|

||

|

||

"ttl": 10

|

||

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The first step is loading information about the bikesharing stations into Redis using data from the `system_information` and `station_information` feeds.

|

||

|

||

The `system_information` feed provides the system ID, which is a short code that can be used to create namespaces for Redis keys. The GBFS spec doesn't specify the format of the system ID, but does guarantee it is globally unique. Many of the bikeshare feeds use short names like coast_bike_share, boise_greenbike, or topeka_metro_bikes for system IDs. Others use familiar geographic abbreviations such as NYC or BA, and one uses a universally unique identifier (UUID). The bikesharing application uses the identifier as a prefix to construct unique keys for the given system.

|

||

|

||

The `station_information` feed provides static information about the sharing stations that comprise the system. Stations are represented by JSON objects with several fields. There are several mandatory fields in the station object that provide the ID, name, and location of the physical bike stations. There are also several optional fields that provide helpful information such as the nearest cross street or accepted payment methods. This is the primary source of information for this part of the bikesharing application.

|

||

|

||

### Building the database

|

||

|

||

I've written a sample application, [load_station_data.py][8], that mimics what would happen in a backend process for loading data from external sources.

|

||

|

||

### Finding the bikeshare stations

|

||

|

||

Loading the bikeshare data starts with the [systems.csv][9] file from the [GBFS repository on GitHub][5].

|

||

|

||

The repository's [systems.csv][9] file provides the discovery URL for registered bikeshare systems with an available GBFS feed. The discovery URL is the starting point for processing bikeshare information.

|

||

|

||

The `load_station_data` application takes each discovery URL found in the systems file and uses it to find the URL for two sub-feeds: system information and station information. The system information feed provides a key piece of information: the unique ID of the system. (Note: the system ID is also provided in the systems.csv file, but some of the identifiers in that file do not match the identifiers in the feeds, so I always fetch the identifier from the feed.) Details on the system, like bikeshare URLs, phone numbers, and emails, could be added in future versions of the application, so the data is stored in a Redis hash using the key `${system_id}:system_info`.

|

||

|

||

### Loading the station data

|

||

|

||

The station information provides data about every station in the system, including the system's location. The `load_station_data` application iterates over every station in the station feed and stores the data about each into a Redis hash using a key of the form `${system_id}:station:${station_id}`. The location of each station is added to a geospatial index for the bikeshare using the `GEOADD` command.

|

||

|

||

### Updating data

|

||

|

||

On subsequent runs, I don't want the code to remove all the feed data from Redis and reload it into an empty Redis database, so I carefully considered how to handle in-place updates of the data.

|

||

|

||

The code starts by loading the dataset with information on all the bikesharing stations for the system being processed into memory. When information is loaded for a station, the station (by key) is removed from the in-memory set of stations. Once all station data is loaded, we're left with a set containing all the station data that must be removed for that system.

|

||

|

||

The application iterates over this set of stations and creates a transaction to delete the station information, remove the station key from the geospatial indexes, and remove the station from the list of stations for the system.

|

||

|

||

### Notes on the code

|

||

|

||

There are a few interesting things to note in [the sample code][8]. First, items are added to the geospatial indexes using the `GEOADD` command but removed with the `ZREM` command. As the underlying implementation of the geospatial type uses sorted sets, items are removed using `ZREM`. A word of caution: For simplicity, the sample code demonstrates working with a single Redis node; the transaction blocks would need to be restructured to run in a cluster environment.

|

||

|

||

If you are using Redis 4.0 (or later), you have some alternatives to the `DELETE` and `HMSET` commands in the code. Redis 4.0 provides the [`UNLINK`][10] command as an asynchronous alternative to the `DELETE` command. `UNLINK` will remove the key from the keyspace, but it reclaims the memory in a separate thread. The [`HMSET`][11] command is [deprecated in Redis 4.0 and the `HSET` command is now variadic][12] (that is, it accepts an indefinite number of arguments).

|

||

|

||

### Notifying clients

|

||

|

||

At the end of the process, a notification is sent to the clients relying on our data. Using the Redis pub/sub mechanism, the notification goes out over the `geobike:station_changed` channel with the ID of the system.

|

||

|

||

### Data model

|

||

|

||

When structuring data in Redis, the most important thing to think about is how you will query the information. The two main queries the bikeshare application needs to support are:

|

||

|

||

* Find stations near us

|

||

* Display information about stations

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Redis provides two main data types that will be useful for storing our data: hashes and sorted sets. The [hash type][13] maps well to the JSON objects that represent stations; since Redis hashes don't enforce a schema, they can be used to store the variable station information.

|

||

|

||

Of course, finding stations geographically requires a geospatial index to search for stations relative to some coordinates. Redis provides [several commands][14] to build up a geospatial index using the [sorted set][15] data structure.

|

||

|

||

We construct keys using the format `${system_id}:station:${station_id}` for the hashes containing information about the stations and keys using the format `${system_id}:stations:location` for the geospatial index used to find stations.

|

||

|

||

### Getting the user's location

|

||

|

||

The next step in building out the application is to determine the user's current location. Most applications accomplish this through built-in services provided by the operating system. The OS can provide applications with a location based on GPS hardware built into the device or approximated from the device's available WiFi networks.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

### Finding stations

|

||

|

||

After the user's location is found, the next step is locating nearby bikesharing stations. Redis' geospatial functions can return information on stations within a given distance of the user's current coordinates. Here's an example of this using the Redis command-line interface.

|

||

|

||

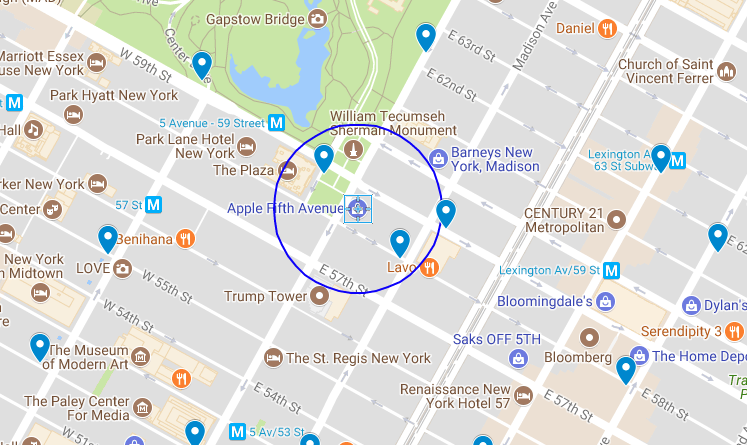

Imagine I'm at the Apple Store on Fifth Avenue in New York City, and I want to head downtown to Mood on West 37th to catch up with my buddy [Swatch][16]. I could take a taxi or the subway, but I'd rather bike. Are there any nearby sharing stations where I could get a bike for my trip?

|

||

|

||

The Apple store is located at 40.76384, -73.97297. According to the map, two bikeshare stations—Grand Army Plaza & Central Park South and East 58th St. & Madison—fall within a 500-foot radius (in blue on the map above) of the store.

|

||

|

||

I can use Redis' `GEORADIUS` command to query the NYC system index for stations within a 500-foot radius:

|

||

```

|

||

127.0.0.1:6379> GEORADIUS NYC:stations:location -73.97297 40.76384 500 ft

|

||

|

||

1) "NYC:station:3457"

|

||

|

||

2) "NYC:station:281"

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Redis returns the two bikeshare locations found within that radius, using the elements in our geospatial index as the keys for the metadata about a particular station. The next step is looking up the names for the two stations:

|

||

```

|

||

127.0.0.1:6379> hget NYC:station:281 name

|

||

|

||

"Grand Army Plaza & Central Park S"

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

127.0.0.1:6379> hget NYC:station:3457 name

|

||

|

||

"E 58 St & Madison Ave"

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Those keys correspond to the stations identified on the map above. If I want, I can add more flags to the `GEORADIUS` command to get a list of elements, their coordinates, and their distance from our current point:

|

||

```

|

||

127.0.0.1:6379> GEORADIUS NYC:stations:location -73.97297 40.76384 500 ft WITHDIST WITHCOORD ASC

|

||

|

||

1) 1) "NYC:station:281"

|

||

|

||

2) "289.1995"

|

||

|

||

3) 1) "-73.97371262311935425"

|

||

|

||

2) "40.76439830559216659"

|

||

|

||

2) 1) "NYC:station:3457"

|

||

|

||

2) "383.1782"

|

||

|

||

3) 1) "-73.97209256887435913"

|

||

|

||

2) "40.76302702144496237"

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Looking up the names associated with those keys generates an ordered list of stations I can choose from. Redis doesn't provide directions or routing capability, so I use the routing features of my device's OS to plot a course from my current location to the selected bike station.

|

||

|

||

The `GEORADIUS` function can be easily implemented inside an API in your favorite development framework to add location functionality to an app.

|

||

|

||

### Other query commands

|

||

|

||

In addition to the `GEORADIUS` command, Redis provides three other commands for querying data from the index: `GEOPOS`, `GEODIST`, and `GEORADIUSBYMEMBER`.

|

||

|

||

The `GEOPOS` command can provide the coordinates for a given element from the geohash. For example, if I know there is a bikesharing station at West 38th and 8th and its ID is 523, then the element name for that station is NYC🚉523. Using Redis, I can find the station's longitude and latitude:

|

||

```

|

||

127.0.0.1:6379> geopos NYC:stations:location NYC:station:523

|

||

|

||

1) 1) "-73.99138301610946655"

|

||

|

||

2) "40.75466497634030105"

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The `GEODIST` command provides the distance between two elements of the index. If I wanted to find the distance between the station at Grand Army Plaza & Central Park South and the station at East 58th St. & Madison, I would issue the following command:

|

||

```

|

||

127.0.0.1:6379> GEODIST NYC:stations:location NYC:station:281 NYC:station:3457 ft

|

||

|

||

"671.4900"

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Finally, the `GEORADIUSBYMEMBER` command is similar to the `GEORADIUS` command, but instead of taking a set of coordinates, the command takes the name of another member of the index and returns all the members within a given radius centered on that member. To find all the stations within 1,000 feet of the Grand Army Plaza & Central Park South, enter the following:

|

||

```

|

||

127.0.0.1:6379> GEORADIUSBYMEMBER NYC:stations:location NYC:station:281 1000 ft WITHDIST

|

||

|

||

1) 1) "NYC:station:281"

|

||

|

||

2) "0.0000"

|

||

|

||

2) 1) "NYC:station:3132"

|

||

|

||

2) "793.4223"

|

||

|

||

3) 1) "NYC:station:2006"

|

||

|

||

2) "911.9752"

|

||

|

||

4) 1) "NYC:station:3136"

|

||

|

||

2) "940.3399"

|

||

|

||

5) 1) "NYC:station:3457"

|

||

|

||

2) "671.4900"

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

While this example focused on using Python and Redis to parse data and build an index of bikesharing system locations, it can easily be generalized to locate restaurants, public transit, or any other type of place developers want to help users find.

|

||

|

||

This article is based on [my presentation][17] at Open Source 101 in Raleigh this year.

|

||

|

||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||

|

||

via: https://opensource.com/article/18/2/building-bikesharing-application-open-source-tools

|

||

|

||

作者:[Tague Griffith][a]

|

||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||

|

||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||

|

||

[a]:https://opensource.com/users/tague

|

||

[1]:https://www.python.org/

|

||

[2]:https://redis.io/

|

||

[3]:https://www.citibikenyc.com/

|

||

[4]:https://www.citibikenyc.com/data-sharing-policy

|

||

[5]:https://github.com/NABSA/gbfs

|

||

[6]:http://nabsa.net/

|

||

[7]:https://www.json.org/

|

||

[8]:https://gist.github.com/tague/5a82d96bcb09ce2a79943ad4c87f6e15

|

||

[9]:https://github.com/NABSA/gbfs/blob/master/systems.csv

|

||

[10]:https://redis.io/commands/unlink

|

||

[11]:https://redis.io/commands/hmset

|

||

[12]:https://raw.githubusercontent.com/antirez/redis/4.0/00-RELEASENOTES

|

||

[13]:https://redis.io/topics/data-types#Hashes

|

||

[14]:https://redis.io/commands#geo

|

||

[15]:https://redis.io/topics/data-types-intro#redis-sorted-sets

|

||

[16]:https://twitter.com/swatchthedog

|

||

[17]:http://opensource101.com/raleigh/talks/building-location-aware-apps-open-source-tools/

|