6.8 KiB

Position text on your screen in Linux with ncurses

Use ncurses in Linux to place text at specific locations on the screen

and enable more user-friendly interfaces.

Most Linux utilities just scroll text from the bottom of the screen. But what if you wanted to position text on the screen, such as for a game or a data display? That's where ncurses comes in.

curses is an old Unix library that supports cursor control on a text terminal screen. The name curses comes from the term cursor control. Years later, others wrote an improved version of curses to add new features, called new curses or ncurses. You can find ncurses in every modern Linux distribution, although the development libraries, header files, and documentation may not be installed by default. For example, on Fedora, you will need to install the ncurses-devel package with this command:

`$ sudo dnf install ncurses-devel`

Using ncurses in a program

To directly address the screen, you'll first need to initialize the ncurses library. Most programs will do that with these three lines:

- initscr(); Initialize the screen and the ncurses code

- cbreak(); Disable buffering and make typed input immediately available

- noecho(); Turn off echo, so user input is not displayed to the screen

These functions are defined in the curses.h header file, which you'll need to include in your program with:

`#include <curses.h>`

After initializing the terminal, you're free to use any of the ncurses functions, some of which we'll explore in a sample program.

When you're done with ncurses and want to go back to regular terminal mode, use endwin(); to reset everything. This command resets any screen colors, moves the cursor to the lower-left of the screen, and makes the cursor visible. You usually do this right before exiting the program.

Addressing the screen

The first thing to know about ncurses is that screen coordinates are row,col, and start in the upper-left at 0,0. ncurses defines two global variables to help you identify the screen size: LINES is the number of lines on the screen, and COLS is the number of columns. The bottom-right position is LINES-1,COLS-1.

For example, if you wanted to move the cursor to line 10 and column 30, you could use the move function with those coordinates:

`move(10, 30);`

Any text you display after that will start at that screen location. To display a single character, use the addch(c) function with a single character. To display a string, use addstr(s) with your string. For formatted output that's similar to printf, use printw(fmt, …) with the usual options.

Moving to a screen location and displaying text is such a common thing that ncurses provides a shortcut to do both at once. The mvaddch(row, col, c) function will display a character at screen location row,col. And the mvaddstr(row, col, s) function will display a string at that location. For a more direct example, using mvaddstr(10, 30, "Welcome to ncurses"); in a program will display the text "Welcome to ncurses" starting at row 10 and column 30. And the line mvaddch(0, 0, '+'); will display a single plus sign in the upper-left corner at row 0 and column 0.

Drawing text to the terminal screen can have a performance impact on certain systems, especially on older hardware terminals. So ncurses lets you "stack up" a bunch of text to display to the screen, then use the refresh() function to make all of those changes visible to the user.

Let's look at a simple example that pulls everything together:

#include <curses.h>

int

main()

{

initscr();

cbreak();

noecho();

mvaddch(0, 0, '+');

mvaddch(LINES - 1, 0, '-');

mvaddstr(10, 30, "press any key to quit");

refresh();

getch();

endwin();

}

The program starts by initializing the terminal, then prints a plus sign in the upper-left corner, a minus in the lower-left corner, and the text "press any key to quit" at row 10 and column 30. The program gets a single character from the keyboard using the getch() function, then uses endwin() to reset the terminal before the program exits completely.

getch() is a useful function that you could use for many things. I often use it as a way to pause before I quit the program. And as with most ncurses functions, there's also a version of getch() called mvgetch(row, col) to move to screen position row,col before waiting for a character.

Compiling with ncurses

If you tried to compile that sample program in the usual way, such as gcc pause.c, you'll probably get a huge list of errors from the linker. That's because the ncurses library is not linked automatically by the GNU C Compiler. Instead, you'll need to load it for linking using the -l ncurses command-line option.

`$ gcc -o pause pause.c -lncurses`

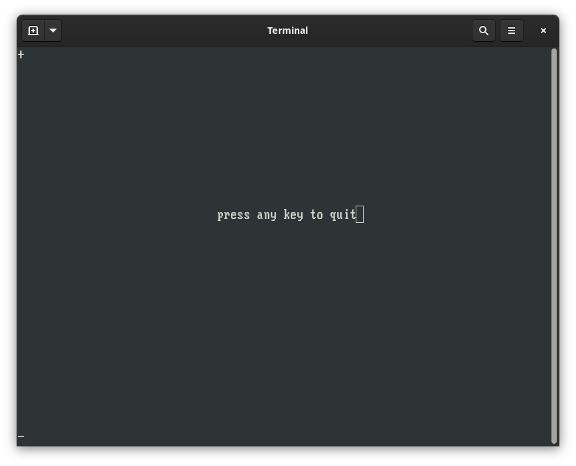

Running the new program will print a simple "press any key to quit" message that's more or less centered on the screen:

Figure 1: A centered "press any key to quit" message in a program.

Building better programs with ncurses

Explore the ncurses library functions to learn about other ways to display text to the screen. You can find a list of all ncurses functions in the man ncurses manual page. This gives a general overview of ncurses and provides a table-like list of the different ncurses functions, with a reference to the manual page that has full details. For example, printw is described in the curs_printw(3X) manual page, which you can view with:

`$ man 3x curs_printw`

or just:

`$ man curs_printw`

With ncurses, you can create more interesting programs. By printing text at specific locations on the screen, you can create games and advanced utilities to run in the terminal.

via: https://opensource.com/article/21/8/ncurses-linux