mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2024-12-29 21:41:00 +08:00

358 lines

17 KiB

Markdown

358 lines

17 KiB

Markdown

Looking at the Lispy side of Perl

|

||

======

|

||

|

||

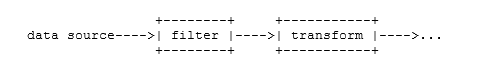

Some programming languages (e.g., C) have named functions only, whereas others (e.g., Lisp, Java, and Perl) have both named and unnamed functions. A lambda is an unnamed function, with Lisp as the language that popularized the term. Lambdas have various uses, but they are particularly well-suited for data-rich applications. Consider this depiction of a data pipeline, with two processing stages shown:

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

### Lambdas and higher-order functions

|

||

|

||

The filter and transform stages can be implemented as higher-order functions—that is, functions that can take a function as an argument. Suppose that the depicted pipeline is part of an accounts-receivable application. The filter stage could consist of a function named `filter_data`, whose single argument is another function—for example, a `high_buyers` function that filters out amounts that fall below a threshold. The transform stage might convert amounts in U.S. dollars to equivalent amounts in euros or some other currency, depending on the function plugged in as the argument to the higher-order `transform_data` function. Changing the filter or the transform behavior requires only plugging in a different function argument to the higher order `filter_data` or `transform_data` functions.

|

||

|

||

Lambdas serve nicely as arguments to higher-order functions for two reasons. First, lambdas can be crafted on the fly, and even written in place as arguments. Second, lambdas encourage the coding of pure functions, which are functions whose behavior depends solely on the argument(s) passed in; such functions have no side effects and thereby promote safe concurrent programs.

|

||

|

||

Perl has a straightforward syntax and semantics for lambdas and higher-order functions, as shown in the following example:

|

||

|

||

### A first look at lambdas in Perl

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

#!/usr/bin/perl

|

||

|

||

use strict;

|

||

use warnings;

|

||

|

||

## References to lambdas that increment, decrement, and do nothing.

|

||

## $_[0] is the argument passed to each lambda.

|

||

my $inc = sub { $_[0] + 1 }; ## could use 'return $_[0] + 1' for clarity

|

||

my $dec = sub { $_[0] - 1 }; ## ditto

|

||

my $nop = sub { $_[0] }; ## ditto

|

||

|

||

sub trace {

|

||

my ($val, $func, @rest) = @_;

|

||

print $val, " ", $func, " ", @rest, "\nHit RETURN to continue...\n";

|

||

<STDIN>;

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

## Apply an operation to a value. The base case occurs when there are

|

||

## no further operations in the list named @rest.

|

||

sub apply {

|

||

my ($val, $first, @rest) = @_;

|

||

trace($val, $first, @rest) if 1; ## 0 to stop tracing

|

||

|

||

return ($val, apply($first->($val), @rest)) if @rest; ## recursive case

|

||

return ($val, $first->($val)); ## base case

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

my $init_val = 0;

|

||

my @ops = ( ## list of lambda references

|

||

$inc, $dec, $dec, $inc,

|

||

$inc, $inc, $inc, $dec,

|

||

$nop, $dec, $dec, $nop,

|

||

$nop, $inc, $inc, $nop

|

||

);

|

||

|

||

## Execute.

|

||

print join(' ', apply($init_val, @ops)), "\n";

|

||

## Final line of output: 0 1 0 -1 0 1 2 3 2 2 1 0 0 0 1 2 2strictwarningstraceSTDINapplytraceapplyapply

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The lispy program shown above highlights the basics of Perl lambdas and higher-order functions. Named functions in Perl start with the keyword `sub` followed by a name:

|

||

```

|

||

sub increment { ... } # named function

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

An unnamed or anonymous function omits the name:

|

||

```

|

||

sub {...} # lambda, or unnamed function

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

In the lispy example, there are three lambdas, and each has a reference to it for convenience. Here, for review, is the `$inc` reference and the lambda referred to:

|

||

```

|

||

my $inc = sub { $_[0] + 1 };

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The lambda itself, the code block to the right of the assignment operator `=`, increments its argument `$_[0]` by 1. The lambda’s body is written in Lisp style; that is, without either an explicit `return` or a semicolon after the incrementing expression. In Perl, as in Lisp, the value of the last expression in a function’s body becomes the returned value if there is no explicit `return` statement. In this example, each lambda has only one expression in its body—a simplification that befits the spirit of lambda programming.

|

||

|

||

The `trace` function in the lispy program helps to clarify how the program works (as I'll illustrate below). The higher-order function `apply`, a nod to a Lisp function of the same name, takes a numeric value as its first argument and a list of lambda references as its second argument. The `apply` function is called initially, at the bottom of the program, with zero as the first argument and the list named `@ops` as the second argument. This list consists of 16 lambda references from among `$inc` (increment a value), `$dec` (decrement a value), and `$nop` (do nothing). The list could contain the lambdas themselves, but the code is easier to write and to understand with the more concise lambda references.

|

||

|

||

The logic of the higher-order `apply` function can be clarified as follows:

|

||

|

||

1. The argument list passed to `apply` in typical Perl fashion is separated into three pieces:

|

||

```

|

||

my ($val, $first, @rest) = @_; ## break the argument list into three elements

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The first element `$val` is a numeric value, initially `0`. The second element `$first` is a lambda reference, one of `$inc` `$dec`, or `$nop`. The third element `@rest` is a list of any remaining lambda references after the first such reference is extracted as `$first`.

|

||

|

||

2. If the list `@rest` is not empty after its first element is removed, then `apply` is called recursively. The two arguments to the recursively invoked `apply` are:

|

||

|

||

* The value generated by applying lambda operation `$first` to numeric value `$val`. For example, if `$first` is the incrementing lambda to which `$inc` refers, and `$val` is 2, then the new first argument to `apply` would be 3.

|

||

* The list of remaining lambda references. Eventually, this list becomes empty because each call to `apply` shortens the list by extracting its first element.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Here is some output from a sample run of the lispy program, with `%` as the command-line prompt:

|

||

```

|

||

% ./lispy.pl

|

||

|

||

0 CODE(0x8f6820) CODE(0x8f68c8)CODE(0x8f68c8)CODE(0x8f6820)CODE(0x8f6820)CODE(0x8f6820)...

|

||

Hit RETURN to continue...

|

||

|

||

1 CODE(0x8f68c8) CODE(0x8f68c8)CODE(0x8f6820)CODE(0x8f6820)CODE(0x8f6820)CODE(0x8f6820)...

|

||

Hit RETURN to continue

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The first output line can be clarified as follows:

|

||

|

||

* The `0` is the numeric value passed as an argument in the initial (and thus non-recursive) call to function `apply`. The argument name is `$val` in `apply`.

|

||

* The `CODE(0x8f6820)` is a reference to one of the lambdas, in this case the lambda to which `$inc` refers. The second argument is thus the address of some lambda code. The argument name is `$first` in `apply`

|

||

* The third piece, the series of `CODE` references, is the list of lambda references beyond the first. The argument name is `@rest` in `apply`.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

The second line of output shown above also deserves a look. The numeric value is now `1`, the result of incrementing `0`: the initial lambda is `$inc` and the initial value is `0`. The extracted reference `CODE(0x8f68c8)` is now `$first`, as this reference is the first element in the `@rest` list after `$inc` has been extracted earlier.

|

||

|

||

Eventually, the `@rest` list becomes empty, which ends the recursive calls to `apply`. In this case, the function `apply` simply returns a list with two elements:

|

||

|

||

1. The numeric value taken in as an argument (in the sample run, 2).

|

||

2. This argument transformed by the lambda (also 2 because the last lambda reference happens to be `$nop` for do nothing).

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

The lispy example underscores that Perl supports lambdas without any special fussy syntax: A lambda is just an unnamed code block, perhaps with a reference to it for convenience. Lambdas themselves, or references to them, can be passed straightforwardly as arguments to higher-order functions such as `apply` in the lispy example. Invoking a lambda through a reference is likewise straightforward. In the `apply` function, the call is:

|

||

```

|

||

$first->($val) ## $first is a lambda reference, $val a numeric argument passed to the lambda

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

### A richer code example

|

||

|

||

The next code example puts a lambda and a higher-order function to practical use. The example implements Conway’s Game of Life, a cellular automaton that can be represented as a matrix of cells. Such a matrix goes through various transformations, each yielding a new generation of cells. The Game of Life is fascinating because even relatively simple initial configurations can lead to quite complex behavior. A quick look at the rules governing cell birth, survival, and death is in order.

|

||

|

||

Consider this 5x5 matrix, with a star representing a live cell and a dash representing a dead one:

|

||

```

|

||

----- ## initial configuration

|

||

--*--

|

||

--*--

|

||

--*--

|

||

-----

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The next generation becomes:

|

||

```

|

||

----- ## next generation

|

||

-----

|

||

-***-

|

||

----

|

||

-----

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

As life continues, the generations oscillate between these two configurations.

|

||

|

||

Here are the rules determining birth, death, and survival for a cell. A given cell has between three neighbors (a corner cell) and eight neighbors (an interior cell):

|

||

|

||

* A dead cell with exactly three live neighbors comes to life.

|

||

* A live cell with more than three live neighbors dies from over-crowding.

|

||

* A live cell with two or three live neighbors survives; hence, a live cell with fewer than two live neighbors dies from loneliness.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

In the initial configuration shown above, the top and bottom live cells die because neither has two or three live neighbors. By contrast, the middle live cell in the initial configuration gains two live neighbors, one on either side, in the next generation.

|

||

|

||

## Conway’s Game of Life

|

||

```

|

||

#!/usr/bin/perl

|

||

|

||

### A simple implementation of Conway's game of life.

|

||

# Usage: ./gol.pl [input file] ;; If no file name given, DefaultInfile is used.

|

||

|

||

use constant Dead => "-";

|

||

use constant Alive => "*";

|

||

use constant DefaultInfile => 'conway.in';

|

||

|

||

use strict;

|

||

use warnings;

|

||

|

||

my $dimension = undef;

|

||

my @matrix = ();

|

||

my $generation = 1;

|

||

|

||

sub read_data {

|

||

my $datafile = DefaultInfile;

|

||

$datafile = shift @ARGV if @ARGV;

|

||

die "File $datafile does not exist.\n" if !-f $datafile;

|

||

open(INFILE, "<$datafile");

|

||

|

||

## Check 1st line for dimension;

|

||

$dimension = <INFILE>;

|

||

die "1st line of input file $datafile not an integer.\n" if $dimension !~ /\d+/;

|

||

|

||

my $record_count = 0;

|

||

while (<INFILE>) {

|

||

chomp($_);

|

||

last if $record_count++ == $dimension;

|

||

die "$_: bad input record -- incorrect length\n" if length($_) != $dimension;

|

||

my @cells = split(//, $_);

|

||

push @matrix, @cells;

|

||

}

|

||

close(INFILE);

|

||

draw_matrix();

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

sub draw_matrix {

|

||

my $n = $dimension * $dimension;

|

||

print "\n\tGeneration $generation\n";

|

||

for (my $i = 0; $i < $n; $i++) {

|

||

print "\n\t" if ($i % $dimension) == 0;

|

||

print $matrix[$i];

|

||

}

|

||

print "\n\n";

|

||

$generation++;

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

sub has_left_neighbor {

|

||

my ($ind) = @_;

|

||

return ($ind % $dimension) != 0;

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

sub has_right_neighbor {

|

||

my ($ind) = @_;

|

||

return (($ind + 1) % $dimension) != 0;

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

sub has_up_neighbor {

|

||

my ($ind) = @_;

|

||

return (int($ind / $dimension)) != 0;

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

sub has_down_neighbor {

|

||

my ($ind) = @_;

|

||

return (int($ind / $dimension) + 1) != $dimension;

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

sub has_left_up_neighbor {

|

||

my ($ind) = @_;

|

||

($ind) && has_up_neighbor($ind);

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

sub has_right_up_neighbor {

|

||

my ($ind) = @_;

|

||

($ind) && has_up_neighbor($ind);

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

sub has_left_down_neighbor {

|

||

my ($ind) = @_;

|

||

($ind) && has_down_neighbor($ind);

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

sub has_right_down_neighbor {

|

||

my ($ind) = @_;

|

||

($ind) && has_down_neighbor($ind);

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

sub compute_cell {

|

||

my ($ind) = @_;

|

||

my @neighbors;

|

||

|

||

# 8 possible neighbors

|

||

push(@neighbors, $ind - 1) if has_left_neighbor($ind);

|

||

push(@neighbors, $ind + 1) if has_right_neighbor($ind);

|

||

push(@neighbors, $ind - $dimension) if has_up_neighbor($ind);

|

||

push(@neighbors, $ind + $dimension) if has_down_neighbor($ind);

|

||

push(@neighbors, $ind - $dimension - 1) if has_left_up_neighbor($ind);

|

||

push(@neighbors, $ind - $dimension + 1) if has_right_up_neighbor($ind);

|

||

push(@neighbors, $ind + $dimension - 1) if has_left_down_neighbor($ind);

|

||

push(@neighbors, $ind + $dimension + 1) if has_right_down_neighbor($ind);

|

||

|

||

my $count = 0;

|

||

foreach my $n (@neighbors) {

|

||

$count++ if $matrix[$n] eq Alive;

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

if ($matrix[$ind] eq Alive) && (($count == 2) || ($count == 3)); ## survival

|

||

if ($matrix[$ind] eq Dead) && ($count == 3); ## birth

|

||

; ## death

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

sub again_or_quit {

|

||

print "RETURN to continue, 'q' to quit.\n";

|

||

my $flag = <STDIN>;

|

||

chomp($flag);

|

||

return ($flag eq 'q') ? 1 : 0;

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

sub animate {

|

||

my @new_matrix;

|

||

my $n = $dimension * $dimension - 1;

|

||

|

||

while (1) { ## loop until user signals stop

|

||

@new_matrix = map {compute_cell($_)} (0..$n); ## generate next matrix

|

||

|

||

splice @matrix; ## empty current matrix

|

||

push @matrix, @new_matrix; ## repopulate matrix

|

||

draw_matrix(); ## display the current matrix

|

||

|

||

last if again_or_quit(); ## continue?

|

||

splice @new_matrix; ## empty temp matrix

|

||

}

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

### Execute

|

||

read_data(); ## read initial configuration from input file

|

||

animate(); ## display and recompute the matrix until user tires

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The gol program (see [Conway’s Game of Life][1]) has almost 140 lines of code, but most of these involve reading the input file, displaying the matrix, and bookkeeping tasks such as determining the number of live neighbors for a given cell. Input files should be configured as follows:

|

||

```

|

||

5

|

||

-----

|

||

--*--

|

||

--*--

|

||

--*--

|

||

-----

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The first record gives the matrix side, in this case 5 for a 5x5 matrix. The remaining rows are the contents, with stars for live cells and spaces for dead ones.

|

||

|

||

The code of primary interest resides in two functions, `animate` and `compute_cell`. The `animate` function constructs the next generation, and this function needs to call `compute_cell` on every cell in order to determine the cell’s new status as either alive or dead. How should the `animate` function be structured?

|

||

|

||

The `animate` function has a `while` loop that iterates until the user decides to terminate the program. Within this `while` loop the high-level logic is straightforward:

|

||

|

||

1. Create the next generation by iterating over the matrix cells, calling function `compute_cell` on each cell to determine its new status. At issue is how best to do the iteration. A loop nested inside the `while `loop would do, of course, but nested loops can be clunky. Another way is to use a higher-order function, as clarified shortly.

|

||

2. Replace the current matrix with the new one.

|

||

3. Display the next generation.

|

||

4. Check if the user wants to continue: if so, continue; otherwise, terminate.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Here, for review, is the call to Perl’s higher-order `map` function, with the function’s name again a nod to Lisp. This call occurs as the first statement within the `while` loop in `animate`:

|

||

```

|

||

while (1) {

|

||

@new_matrix = map {compute_cell($_)} (0..$n); ## generate next matrixcompute_cell

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The `map` function takes two arguments: an unnamed code block (a lambda!), and a list of values passed to this code block one at a time. In this example, the code block calls the `compute_cell` function with one of the matrix indexes, 0 through the matrix size - 1. Although the matrix is displayed as two-dimensional, it is implemented as a one-dimensional list.

|

||

|

||

Higher-order functions such as `map` encourage the code brevity for which Perl is famous. My view is that such functions also make code easier to write and to understand, as they dispense with the required but messy details of loops. In any case, lambdas and higher-order functions make up the Lispy side of Perl.

|

||

|

||

If you're interested in more detail, I recommend Mark Jason Dominus's book, [Higher-Order Perl][2].

|

||

|

||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||

|

||

via: https://opensource.com/article/18/5/looking-lispy-side-perl

|

||

|

||

作者:[Marty Kalin][a]

|

||

选题:[lujun9972](https://github.com/lujun9972)

|

||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||

|

||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||

|

||

[a]:https://opensource.com/users/mkalindepauledu

|

||

[1]:https://trello-attachments.s3.amazonaws.com/575088ec94ca6ac38b49b30e/5ad4daf12f6b6a3ac2318d28/c0700c7379983ddf61f5ab5ab4891f0c/lispyPerl.html#gol (Conway’s Game of Life)

|

||

[2]:https://www.elsevier.com/books/higher-order-perl/dominus/978-1-55860-701-9

|