mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2024-12-26 21:30:55 +08:00

970 lines

28 KiB

Markdown

970 lines

28 KiB

Markdown

Go on very small hardware (Part 2)

|

||

============================================================

|

||

|

||

|

||

[][1]

|

||

|

||

At the end of the [first part][2] of this article I promised to write something about _interfaces_ . I don’t want to write here a complete or even brief lecture about the interfaces. Instead, I’ll show a simple example how to define and use an interface, and then, how to take advantage of ubiquitous _io.Writer_ interface. There will also be a few words about _reflection_ and _semihosting_ .

|

||

|

||

Interfaces are a crucial part of Go language. If you want to learn more about them, I suggest to read [Effective Go][3] and [Russ Cox article][4].

|

||

|

||

### Concurrent Blinky – revisited

|

||

|

||

When you read the code of previous examples you probably noticed a counterintuitive way to turn the LED on or off. The _Set_ method was used to turn the LED off and the _Clear_ method was used to turn the LED on. This is due to driving the LEDs in open-drain configuration. What we can do to make the code less confusing? Let’s define the _LED_ type with _On_ and _Off_ methods:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

type LED struct {

|

||

pin gpio.Pin

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

func (led LED) On() {

|

||

led.pin.Clear()

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

func (led LED) Off() {

|

||

led.pin.Set()

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Now we can simply call `led.On()` and `led.Off()` which no longer raises any doubts.

|

||

|

||

In all previous examples I tried to use the same open-drain configuration to don’t complicate the code. But in the last example, it would be easier for me to connect the third LED between GND and PA3 pins and configure PA3 in push-pull mode. The next example will use a LED connected this way.

|

||

|

||

But our new _LED_ type doesn’t support the push-pull configuration. In fact, we should call it _OpenDrainLED_ and define another _PushPullLED_ type:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

type PushPullLED struct {

|

||

pin gpio.Pin

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

func (led PushPullLED) On() {

|

||

led.pin.Set()

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

func (led PushPullLED) Off() {

|

||

led.pin.Clear()

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Note, that both types have the same methods that work the same. It would be nice if the code that operates on LEDs could use both types, without paying attention to which one it uses at the moment. The _interface type_ comes to help:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

package main

|

||

|

||

import (

|

||

"delay"

|

||

|

||

"stm32/hal/gpio"

|

||

"stm32/hal/system"

|

||

"stm32/hal/system/timer/systick"

|

||

)

|

||

|

||

type LED interface {

|

||

On()

|

||

Off()

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

type PushPullLED struct{ pin gpio.Pin }

|

||

|

||

func (led PushPullLED) On() {

|

||

led.pin.Set()

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

func (led PushPullLED) Off() {

|

||

led.pin.Clear()

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

func MakePushPullLED(pin gpio.Pin) PushPullLED {

|

||

pin.Setup(&gpio.Config{Mode: gpio.Out, Driver: gpio.PushPull})

|

||

return PushPullLED{pin}

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

type OpenDrainLED struct{ pin gpio.Pin }

|

||

|

||

func (led OpenDrainLED) On() {

|

||

led.pin.Clear()

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

func (led OpenDrainLED) Off() {

|

||

led.pin.Set()

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

func MakeOpenDrainLED(pin gpio.Pin) OpenDrainLED {

|

||

pin.Setup(&gpio.Config{Mode: gpio.Out, Driver: gpio.OpenDrain})

|

||

return OpenDrainLED{pin}

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

var led1, led2 LED

|

||

|

||

func init() {

|

||

system.SetupPLL(8, 1, 48/8)

|

||

systick.Setup(2e6)

|

||

|

||

gpio.A.EnableClock(false)

|

||

led1 = MakeOpenDrainLED(gpio.A.Pin(4))

|

||

led2 = MakePushPullLED(gpio.A.Pin(3))

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

func blinky(led LED, period int) {

|

||

for {

|

||

led.On()

|

||

delay.Millisec(100)

|

||

led.Off()

|

||

delay.Millisec(period - 100)

|

||

}

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

func main() {

|

||

go blinky(led1, 500)

|

||

blinky(led2, 1000)

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

We’ve defined _LED_ interface that has two methods: _On_ and _Off_ . The _PushPullLED_ and _OpenDrainLED_ types represent two ways of driving LEDs. We also defined two _Make_ _*LED_ functions which act as constructors. Both types implement the _LED_ interface, so the values of these types can be assigned to the variables of type _LED_ :

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

led1 = MakeOpenDrainLED(gpio.A.Pin(4))

|

||

led2 = MakePushPullLED(gpio.A.Pin(3))

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

In this case the assignability is checked at compile time. After the assignment the _led1_ variable contains `OpenDrainLED{gpio.A.Pin(4)}` and a pointer to the method set of the _OpenDrainLED_ type. The `led1.On()` call roughly corresponds to the following C code:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

led1.methods->On(led1.value)

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

As you can see, this is quite inexpensive abstraction if only consider the function call overhead.

|

||

|

||

But any assigment to an interface causes to include a lot of information about the assigned type. There can be a lot information in case of complex type which consists of many other types:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

$ egc

|

||

$ arm-none-eabi-size cortexm0.elf

|

||

text data bss dec hex filename

|

||

10356 196 212 10764 2a0c cortexm0.elf

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

If we don’t use [reflection][5] we can save some bytes by avoid to include the names of types and struct fields:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

$ egc -nf -nt

|

||

$ arm-none-eabi-size cortexm0.elf

|

||

text data bss dec hex filename

|

||

10312 196 212 10720 29e0 cortexm0.elf

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The resulted binary still contains some necessary information about types and full information about all exported methods (with names). This information is need for checking assignability at runtime, mainly when you assign one value stored in the interface variable to any other variable.

|

||

|

||

We can also remove type and field names from imported packages by recompiling them all:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

$ cd $HOME/emgo

|

||

$ ./clean.sh

|

||

$ cd $HOME/firstemgo

|

||

$ egc -nf -nt

|

||

$ arm-none-eabi-size cortexm0.elf

|

||

text data bss dec hex filename

|

||

10272 196 212 10680 29b8 cortexm0.elf

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Let’s load this program to see does it work as expected. This time we’ll use the [st-flash][6] command:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

$ arm-none-eabi-objcopy -O binary cortexm0.elf cortexm0.bin

|

||

$ st-flash write cortexm0.bin 0x8000000

|

||

st-flash 1.4.0-33-gd76e3c7

|

||

2018-04-10T22:04:34 INFO usb.c: -- exit_dfu_mode

|

||

2018-04-10T22:04:34 INFO common.c: Loading device parameters....

|

||

2018-04-10T22:04:34 INFO common.c: Device connected is: F0 small device, id 0x10006444

|

||

2018-04-10T22:04:34 INFO common.c: SRAM size: 0x1000 bytes (4 KiB), Flash: 0x4000 bytes (16 KiB) in pages of 1024 bytes

|

||

2018-04-10T22:04:34 INFO common.c: Attempting to write 10468 (0x28e4) bytes to stm32 address: 134217728 (0x8000000)

|

||

Flash page at addr: 0x08002800 erased

|

||

2018-04-10T22:04:34 INFO common.c: Finished erasing 11 pages of 1024 (0x400) bytes

|

||

2018-04-10T22:04:34 INFO common.c: Starting Flash write for VL/F0/F3/F1_XL core id

|

||

2018-04-10T22:04:34 INFO flash_loader.c: Successfully loaded flash loader in sram

|

||

11/11 pages written

|

||

2018-04-10T22:04:35 INFO common.c: Starting verification of write complete

|

||

2018-04-10T22:04:35 INFO common.c: Flash written and verified! jolly good!

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

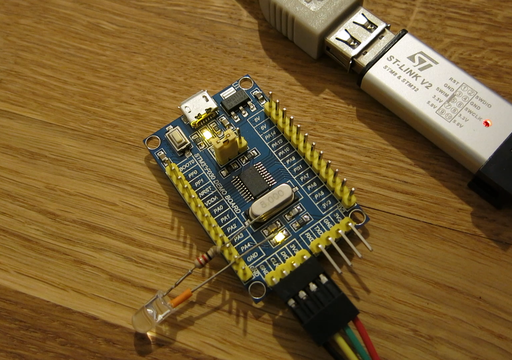

I didn’t connected the NRST signal to the programmer so the _—reset_ option can’t be used and the reset button have to be pressed to run the program.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

It seems that the _st-flash_ works a bit unreliably with this board (often requires reseting the ST-LINK dongle). Additionally, the current version doesn’t issue the reset command over SWD (uses only NRST signal). The software reset isn’t realiable however it usually works and lack of it introduces inconvenience. For this board-programmer pair the _OpenOCD_ works much better.

|

||

|

||

### UART

|

||

|

||

UART (Universal Aynchronous Receiver-Transmitter) is still one of the most important peripherals of today’s microcontrollers. Its advantage is unique combination of the following properties:

|

||

|

||

* relatively high speed,

|

||

|

||

* only two signal lines (even one in case of half-duplex communication),

|

||

|

||

* symmetry of roles,

|

||

|

||

* synchronous in-band signaling about new data (start bit),

|

||

|

||

* accurate timing inside transmitted word.

|

||

|

||

This causes that UART, originally intedned to transmit asynchronous messages consisting of 7-9 bit words, is also used to efficiently implement various other phisical protocols such as used by [WS28xx LEDs][7] or [1-wire][8] devices.

|

||

|

||

However, we will use the UART in its usual role: to printing text messages from our program.

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

package main

|

||

|

||

import (

|

||

"io"

|

||

"rtos"

|

||

|

||

"stm32/hal/dma"

|

||

"stm32/hal/gpio"

|

||

"stm32/hal/irq"

|

||

"stm32/hal/system"

|

||

"stm32/hal/system/timer/systick"

|

||

"stm32/hal/usart"

|

||

)

|

||

|

||

var tts *usart.Driver

|

||

|

||

func init() {

|

||

system.SetupPLL(8, 1, 48/8)

|

||

systick.Setup(2e6)

|

||

|

||

gpio.A.EnableClock(true)

|

||

tx := gpio.A.Pin(9)

|

||

|

||

tx.Setup(&gpio.Config{Mode: gpio.Alt})

|

||

tx.SetAltFunc(gpio.USART1_AF1)

|

||

d := dma.DMA1

|

||

d.EnableClock(true)

|

||

tts = usart.NewDriver(usart.USART1, d.Channel(2, 0), nil, nil)

|

||

tts.Periph().EnableClock(true)

|

||

tts.Periph().SetBaudRate(115200)

|

||

tts.Periph().Enable()

|

||

tts.EnableTx()

|

||

|

||

rtos.IRQ(irq.USART1).Enable()

|

||

rtos.IRQ(irq.DMA1_Channel2_3).Enable()

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

func main() {

|

||

io.WriteString(tts, "Hello, World!\r\n")

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

func ttsISR() {

|

||

tts.ISR()

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

func ttsDMAISR() {

|

||

tts.TxDMAISR()

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

//c:__attribute__((section(".ISRs")))

|

||

var ISRs = [...]func(){

|

||

irq.USART1: ttsISR,

|

||

irq.DMA1_Channel2_3: ttsDMAISR,

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

You can find this code slightly complicated but for now there is no simpler UART driver in STM32 HAL (simple polling driver will be probably useful in some cases). The _usart.Driver_ is efficient driver that uses DMA and interrupts to ofload the CPU.

|

||

|

||

STM32 USART peripheral provides traditional UART and its synchronous version. To use it as output we have to connect its Tx signal to the right GPIO pin:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

tx.Setup(&gpio.Config{Mode: gpio.Alt})

|

||

tx.SetAltFunc(gpio.USART1_AF1)

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The _usart.Driver_ is configured in Tx-only mode (rxdma and rxbuf are set to nil):

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

tts = usart.NewDriver(usart.USART1, d.Channel(2, 0), nil, nil)

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

We use its _WriteString_ method to print the famous sentence. Let’s clean everything and compile this program:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

$ cd $HOME/emgo

|

||

$ ./clean.sh

|

||

$ cd $HOME/firstemgo

|

||

$ egc

|

||

$ arm-none-eabi-size cortexm0.elf

|

||

text data bss dec hex filename

|

||

12728 236 176 13140 3354 cortexm0.elf

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

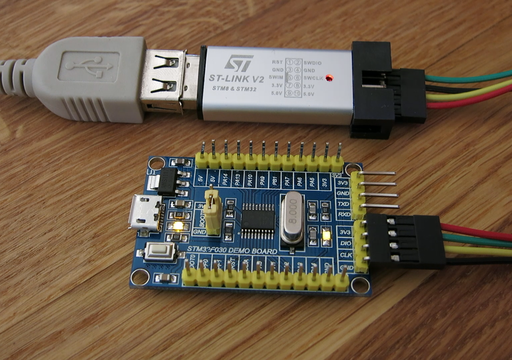

To see something you need an UART peripheral in your PC.

|

||

|

||

**Do not use RS232 port or USB to RS232 converter!**

|

||

|

||

The STM32 family uses 3.3 V logic but RS232 can produce from -15 V to +15 V which will probably demage your MCU. You need USB to UART converter that uses 3.3 V logic. Popular converters are based on FT232 or CP2102 chips.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

You also need some terminal emulator program (I prefer [picocom][9]). Flash the new image, run the terminal emulator and press the reset button a few times:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

$ openocd -d0 -f interface/stlink.cfg -f target/stm32f0x.cfg -c 'init; program cortexm0.elf; reset run; exit'

|

||

Open On-Chip Debugger 0.10.0+dev-00319-g8f1f912a (2018-03-07-19:20)

|

||

Licensed under GNU GPL v2

|

||

For bug reports, read

|

||

http://openocd.org/doc/doxygen/bugs.html

|

||

debug_level: 0

|

||

adapter speed: 1000 kHz

|

||

adapter_nsrst_delay: 100

|

||

none separate

|

||

adapter speed: 950 kHz

|

||

target halted due to debug-request, current mode: Thread

|

||

xPSR: 0xc1000000 pc: 0x080016f4 msp: 0x20000a20

|

||

adapter speed: 4000 kHz

|

||

** Programming Started **

|

||

auto erase enabled

|

||

target halted due to breakpoint, current mode: Thread

|

||

xPSR: 0x61000000 pc: 0x2000003a msp: 0x20000a20

|

||

wrote 13312 bytes from file cortexm0.elf in 1.020185s (12.743 KiB/s)

|

||

** Programming Finished **

|

||

adapter speed: 950 kHz

|

||

$

|

||

$ picocom -b 115200 /dev/ttyUSB0

|

||

picocom v3.1

|

||

|

||

port is : /dev/ttyUSB0

|

||

flowcontrol : none

|

||

baudrate is : 115200

|

||

parity is : none

|

||

databits are : 8

|

||

stopbits are : 1

|

||

escape is : C-a

|

||

local echo is : no

|

||

noinit is : no

|

||

noreset is : no

|

||

hangup is : no

|

||

nolock is : no

|

||

send_cmd is : sz -vv

|

||

receive_cmd is : rz -vv -E

|

||

imap is :

|

||

omap is :

|

||

emap is : crcrlf,delbs,

|

||

logfile is : none

|

||

initstring : none

|

||

exit_after is : not set

|

||

exit is : no

|

||

|

||

Type [C-a] [C-h] to see available commands

|

||

Terminal ready

|

||

Hello, World!

|

||

Hello, World!

|

||

Hello, World!

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Every press of the reset button produces new “Hello, World!” line. Everything works as expected.

|

||

|

||

To see bi-directional UART code for this MCU check out [this example][10].

|

||

|

||

### io.Writer

|

||

|

||

The _io.Writer_ interface is probably the second most commonly used interface type in Go, right after the _error_ interface. Its definition looks like this:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

type Writer interface {

|

||

Write(p []byte) (n int, err error)

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

_usart.Driver_ implements _io.Writer_ so we can replace:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

tts.WriteString("Hello, World!\r\n")

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

with

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

io.WriteString(tts, "Hello, World!\r\n")

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Additionally you need to add the _io_ package to the _import_ section.

|

||

|

||

The declaration of _io.WriteString_ function looks as follows:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

func WriteString(w Writer, s string) (n int, err error)

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

As you can see, the _io.WriteString_ allows to write strings using any type that implements _io.Writer_ interface. Internally it check does the underlying type has _WriteString_ method and uses it instead of _Write_ if available.

|

||

|

||

Let’s compile the modified program:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

$ egc

|

||

$ arm-none-eabi-size cortexm0.elf

|

||

text data bss dec hex filename

|

||

15456 320 248 16024 3e98 cortexm0.elf

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

As you can see, _io.WriteString_ causes a significant increase in the size of the binary: 15776 - 12964 = 2812 bytes. There isn’t too much space left on the Flash. What caused such a drastic increase in size?

|

||

|

||

Using the command:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

arm-none-eabi-nm --print-size --size-sort --radix=d cortexm0.elf

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

we can print all symbols ordered by its size for both cases. By filtering and analyzing the obtained data (awk, diff) we can find about 80 new symbols. The ten largest are:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

> 00000062 T stm32$hal$usart$Driver$DisableRx

|

||

> 00000072 T stm32$hal$usart$Driver$RxDMAISR

|

||

> 00000076 T internal$Type$Implements

|

||

> 00000080 T stm32$hal$usart$Driver$EnableRx

|

||

> 00000084 t errors$New

|

||

> 00000096 R $8$stm32$hal$usart$Driver$$

|

||

> 00000100 T stm32$hal$usart$Error$Error

|

||

> 00000360 T io$WriteString

|

||

> 00000660 T stm32$hal$usart$Driver$Read

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

So, even though we don’t use the _usart.Driver.Read_ method it was compiled in, same as _DisableRx_ , _RxDMAISR_ , _EnableRx_ and other not mentioned above. Unfortunately, if you assign something to the interface, its full method set is required (with all dependences). This isn’t a problem for a large programs that use most of the methods anyway. But for our simple one it’s a huge burden.

|

||

|

||

We’re already close to the limits of our MCU but let’s try to print some numbers (you need to replace _io_ package with _strconv_ in _import_ section):

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

func main() {

|

||

a := 12

|

||

b := -123

|

||

|

||

tts.WriteString("a = ")

|

||

strconv.WriteInt(tts, a, 10, 0, 0)

|

||

tts.WriteString("\r\n")

|

||

tts.WriteString("b = ")

|

||

strconv.WriteInt(tts, b, 10, 0, 0)

|

||

tts.WriteString("\r\n")

|

||

|

||

tts.WriteString("hex(a) = ")

|

||

strconv.WriteInt(tts, a, 16, 0, 0)

|

||

tts.WriteString("\r\n")

|

||

tts.WriteString("hex(b) = ")

|

||

strconv.WriteInt(tts, b, 16, 0, 0)

|

||

tts.WriteString("\r\n")

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

As in the case of _io.WriteString_ function, the first argument of the _strconv.WriteInt_ is of type _io.Writer_ .

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

$ egc

|

||

/usr/local/arm/bin/arm-none-eabi-ld: /home/michal/firstemgo/cortexm0.elf section `.rodata' will not fit in region `Flash'

|

||

/usr/local/arm/bin/arm-none-eabi-ld: region `Flash' overflowed by 692 bytes

|

||

exit status 1

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

This time we’ve run out of space. Let’s try to slim down the information about types:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

$ cd $HOME/emgo

|

||

$ ./clean.sh

|

||

$ cd $HOME/firstemgo

|

||

$ egc -nf -nt

|

||

$ arm-none-eabi-size cortexm0.elf

|

||

text data bss dec hex filename

|

||

15876 316 320 16512 4080 cortexm0.elf

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

It was close, but we fit. Let’s load and run this code:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

a = 12

|

||

b = -123

|

||

hex(a) = c

|

||

hex(b) = -7b

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The _strconv_ package in Emgo is quite different from its archetype in Go. It is intended for direct use to write formatted numbers and in many cases can replace heavy _fmt_ package. That’s why the function names start with _Write_ instead of _Format_ and have additional two parameters. Below is an example of their use:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

func main() {

|

||

b := -123

|

||

strconv.WriteInt(tts, b, 10, 0, 0)

|

||

tts.WriteString("\r\n")

|

||

strconv.WriteInt(tts, b, 10, 6, ' ')

|

||

tts.WriteString("\r\n")

|

||

strconv.WriteInt(tts, b, 10, 6, '0')

|

||

tts.WriteString("\r\n")

|

||

strconv.WriteInt(tts, b, 10, 6, '.')

|

||

tts.WriteString("\r\n")

|

||

strconv.WriteInt(tts, b, 10, -6, ' ')

|

||

tts.WriteString("\r\n")

|

||

strconv.WriteInt(tts, b, 10, -6, '0')

|

||

tts.WriteString("\r\n")

|

||

strconv.WriteInt(tts, b, 10, -6, '.')

|

||

tts.WriteString("\r\n")

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

There is its output:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

-123

|

||

-123

|

||

-00123

|

||

..-123

|

||

-123

|

||

-123

|

||

-123..

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

### Unix streams and Morse code

|

||

|

||

Thanks to the fact that most of the functions that write something use _io.Writer_ instead of concrete type (eg. _FILE_ in C) we get a functionality similar to _Unix streams_ . In Unix we can easily combine simple commands to perform larger tasks. For example, we can write text to the file this way:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

echo "Hello, World!" > file.txt

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The `>` operator writes the output stream of the preceding command to the file. There is also `|`operator that connects output and input streams of adjacent commands.

|

||

|

||

Thanks to the streams we can easily convert/filter output of any command. For example, to convert all letters to uppercase we can filter the echo’s output through _tr_ command:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

echo "Hello, World!" | tr a-z A-Z > file.txt

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

To show the analogy between _io.Writer_ and Unix streams let’s write our:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

io.WriteString(tts, "Hello, World!\r\n")

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

in the following pseudo-unix form:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

io.WriteString "Hello, World!" | usart.Driver usart.USART1

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The next example will show how to do this:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

io.WriteString "Hello, World!" | MorseWriter | usart.Driver usart.USART1

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Let’s create a simple encoder that encodes the text written to it using Morse coding:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

type MorseWriter struct {

|

||

W io.Writer

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

func (w *MorseWriter) Write(s []byte) (int, error) {

|

||

var buf [8]byte

|

||

for n, c := range s {

|

||

switch {

|

||

case c == '\n':

|

||

c = ' ' // Replace new lines with spaces.

|

||

case 'a' <= c && c <= 'z':

|

||

c -= 'a' - 'A' // Convert to upper case.

|

||

}

|

||

if c < ' ' || 'Z' < c {

|

||

continue // c is outside ASCII [' ', 'Z']

|

||

}

|

||

var symbol morseSymbol

|

||

if c == ' ' {

|

||

symbol.length = 1

|

||

buf[0] = ' '

|

||

} else {

|

||

symbol = morseSymbols[c-'!']

|

||

for i := uint(0); i < uint(symbol.length); i++ {

|

||

if (symbol.code>>i)&1 != 0 {

|

||

buf[i] = '-'

|

||

} else {

|

||

buf[i] = '.'

|

||

}

|

||

}

|

||

}

|

||

buf[symbol.length] = ' '

|

||

if _, err := w.W.Write(buf[:symbol.length+1]); err != nil {

|

||

return n, err

|

||

}

|

||

}

|

||

return len(s), nil

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

type morseSymbol struct {

|

||

code, length byte

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

//emgo:const

|

||

var morseSymbols = [...]morseSymbol{

|

||

{1<<0 | 1<<1 | 1<<2, 4}, // ! ---.

|

||

{1<<1 | 1<<4, 6}, // " .-..-.

|

||

{}, // #

|

||

{1<<3 | 1<<6, 7}, // $ ...-..-

|

||

|

||

// Some code omitted...

|

||

|

||

{1<<0 | 1<<3, 4}, // X -..-

|

||

{1<<0 | 1<<2 | 1<<3, 4}, // Y -.--

|

||

{1<<0 | 1<<1, 4}, // Z --..

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

You can find the full _morseSymbols_ array [here][11]. The `//emgo:const` directive ensures that _morseSymbols_ array won’t be copied to the RAM.

|

||

|

||

Now we can print our sentence in two ways:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

func main() {

|

||

s := "Hello, World!\r\n"

|

||

mw := &MorseWriter{tts}

|

||

|

||

io.WriteString(tts, s)

|

||

io.WriteString(mw, s)

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

We use the pointer to the _MorseWriter_ `&MorseWriter{tts}` instead os simple `MorseWriter{tts}` value beacuse the _MorseWriter_ is to big to fit into an interface variable.

|

||

|

||

Emgo, unlike Go, doesn’t dynamically allocate memory for value stored in interface variable. The interface type has limited size, equal to the size of three pointers (to fit _slice_ ) or two _float64_ (to fit _complex128_ ), what is bigger. It can directly store values of all basic types and small structs/arrays but for bigger values you must use pointers.

|

||

|

||

Let’s compile this code and see its output:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

$ egc

|

||

$ arm-none-eabi-size cortexm0.elf

|

||

text data bss dec hex filename

|

||

15152 324 248 15724 3d6c cortexm0.elf

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

Hello, World!

|

||

.... . .-.. .-.. --- --..-- .-- --- .-. .-.. -.. ---.

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

### The Ultimate Blinky

|

||

|

||

The _Blinky_ is hardware equivalent of _Hello, World!_ program. Once we have a Morse encoder we can easly combine both to obtain the _Ultimate Blinky_ program:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

package main

|

||

|

||

import (

|

||

"delay"

|

||

"io"

|

||

|

||

"stm32/hal/gpio"

|

||

"stm32/hal/system"

|

||

"stm32/hal/system/timer/systick"

|

||

)

|

||

|

||

var led gpio.Pin

|

||

|

||

func init() {

|

||

system.SetupPLL(8, 1, 48/8)

|

||

systick.Setup(2e6)

|

||

|

||

gpio.A.EnableClock(false)

|

||

led = gpio.A.Pin(4)

|

||

|

||

cfg := gpio.Config{Mode: gpio.Out, Driver: gpio.OpenDrain, Speed: gpio.Low}

|

||

led.Setup(&cfg)

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

type Telegraph struct {

|

||

Pin gpio.Pin

|

||

Dotms int // Dot length [ms]

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

func (t Telegraph) Write(s []byte) (int, error) {

|

||

for _, c := range s {

|

||

switch c {

|

||

case '.':

|

||

t.Pin.Clear()

|

||

delay.Millisec(t.Dotms)

|

||

t.Pin.Set()

|

||

delay.Millisec(t.Dotms)

|

||

case '-':

|

||

t.Pin.Clear()

|

||

delay.Millisec(3 * t.Dotms)

|

||

t.Pin.Set()

|

||

delay.Millisec(t.Dotms)

|

||

case ' ':

|

||

delay.Millisec(3 * t.Dotms)

|

||

}

|

||

}

|

||

return len(s), nil

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

func main() {

|

||

telegraph := &MorseWriter{Telegraph{led, 100}}

|

||

for {

|

||

io.WriteString(telegraph, "Hello, World! ")

|

||

}

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

// Some code omitted...

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

In the above example I omitted the definition of _MorseWriter_ type because it was shown earlier. The full version is available [here][12]. Let’s compile it and run:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

$ egc

|

||

$ arm-none-eabi-size cortexm0.elf

|

||

text data bss dec hex filename

|

||

11772 244 244 12260 2fe4 cortexm0.elf

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

### Reflection

|

||

|

||

Yes, Emgo supports [reflection][13]. The _reflect_ package isn’t complete yet but that what is done is enough to implement _fmt.Print_ family of functions. Let’s see what can we do on our small MCU.

|

||

|

||

To reduce memory usage we will use [semihosting][14] as standard output. For convenience, we also write simple _println_ function which to some extent mimics _fmt.Println_ .

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

package main

|

||

|

||

import (

|

||

"debug/semihosting"

|

||

"reflect"

|

||

"strconv"

|

||

|

||

"stm32/hal/system"

|

||

"stm32/hal/system/timer/systick"

|

||

)

|

||

|

||

var stdout semihosting.File

|

||

|

||

func init() {

|

||

system.SetupPLL(8, 1, 48/8)

|

||

systick.Setup(2e6)

|

||

|

||

var err error

|

||

stdout, err = semihosting.OpenFile(":tt", semihosting.W)

|

||

for err != nil {

|

||

}

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

type stringer interface {

|

||

String() string

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

func println(args ...interface{}) {

|

||

for i, a := range args {

|

||

if i > 0 {

|

||

stdout.WriteString(" ")

|

||

}

|

||

switch v := a.(type) {

|

||

case string:

|

||

stdout.WriteString(v)

|

||

case int:

|

||

strconv.WriteInt(stdout, v, 10, 0, 0)

|

||

case bool:

|

||

strconv.WriteBool(stdout, v, 't', 0, 0)

|

||

case stringer:

|

||

stdout.WriteString(v.String())

|

||

default:

|

||

stdout.WriteString("%unknown")

|

||

}

|

||

}

|

||

stdout.WriteString("\r\n")

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

type S struct {

|

||

A int

|

||

B bool

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

func main() {

|

||

p := &S{-123, true}

|

||

|

||

v := reflect.ValueOf(p)

|

||

|

||

println("kind(p) =", v.Kind())

|

||

println("kind(*p) =", v.Elem().Kind())

|

||

println("type(*p) =", v.Elem().Type())

|

||

|

||

v = v.Elem()

|

||

|

||

println("*p = {")

|

||

for i := 0; i < v.NumField(); i++ {

|

||

ft := v.Type().Field(i)

|

||

fv := v.Field(i)

|

||

println(" ", ft.Name(), ":", fv.Interface())

|

||

}

|

||

println("}")

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The _semihosting.OpenFile_ function allows to open/create file on the host side. The special path _:tt_ corresponds to host’s standard output.

|

||

|

||

The _println_ function accepts arbitrary number of arguments, each of arbitrary type:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

func println(args ...interface{})

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

It’s possible because any type implements the empty interface _interface{}_ . The _println_ uses [type switch][15] to print strings, integers and booleans:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

switch v := a.(type) {

|

||

case string:

|

||

stdout.WriteString(v)

|

||

case int:

|

||

strconv.WriteInt(stdout, v, 10, 0, 0)

|

||

case bool:

|

||

strconv.WriteBool(stdout, v, 't', 0, 0)

|

||

case stringer:

|

||

stdout.WriteString(v.String())

|

||

default:

|

||

stdout.WriteString("%unknown")

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Additionally it supports any type that implements _stringer_ interface, that is, any type that has _String()_ method. In any _case_ clause the _v_ variable has the right type, same as listed after _case_ keyword.

|

||

|

||

The `reflect.ValueOf(p)` returns _p_ in the form that allows to analyze its type and content programmatically. As you can see, we can even dereference pointers using `v.Elem()` and print all struct fields with their names.

|

||

|

||

Let’s try to compile this code. For now let’s see what will come out if compiled without type and field names:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

$ egc -nt -nf

|

||

$ arm-none-eabi-size cortexm0.elf

|

||

text data bss dec hex filename

|

||

16028 216 312 16556 40ac cortexm0.elf

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Only 140 free bytes left on the Flash. Let’s load it using OpenOCD with semihosting enabled:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

$ openocd -d0 -f interface/stlink.cfg -f target/stm32f0x.cfg -c 'init; program cortexm0.elf; arm semihosting enable; reset run'

|

||

Open On-Chip Debugger 0.10.0+dev-00319-g8f1f912a (2018-03-07-19:20)

|

||

Licensed under GNU GPL v2

|

||

For bug reports, read

|

||

http://openocd.org/doc/doxygen/bugs.html

|

||

debug_level: 0

|

||

adapter speed: 1000 kHz

|

||

adapter_nsrst_delay: 100

|

||

none separate

|

||

adapter speed: 950 kHz

|

||

target halted due to debug-request, current mode: Thread

|

||

xPSR: 0xc1000000 pc: 0x08002338 msp: 0x20000a20

|

||

adapter speed: 4000 kHz

|

||

** Programming Started **

|

||

auto erase enabled

|

||

target halted due to breakpoint, current mode: Thread

|

||

xPSR: 0x61000000 pc: 0x2000003a msp: 0x20000a20

|

||

wrote 16384 bytes from file cortexm0.elf in 0.700133s (22.853 KiB/s)

|

||

** Programming Finished **

|

||

semihosting is enabled

|

||

adapter speed: 950 kHz

|

||

kind(p) = ptr

|

||

kind(*p) = struct

|

||

type(*p) =

|

||

*p = {

|

||

X. : -123

|

||

X. : true

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

If you’ve actually run this code, you noticed that semihosting is slow, especially if you write a byte after byte (buffering helps).

|

||

|

||

As you can see, there is no type name for `*p` and all struct fields have the same _X._ name. Let’s compile this program again, this time without _-nt -nf_ options:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

$ egc

|

||

$ arm-none-eabi-size cortexm0.elf

|

||

text data bss dec hex filename

|

||

16052 216 312 16580 40c4 cortexm0.elf

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Now the type and field names have been included but only these defined in ~~_main.go_ file~~ _main_ package. The output of our program looks as follows:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

kind(p) = ptr

|

||

kind(*p) = struct

|

||

type(*p) = S

|

||

*p = {

|

||

A : -123

|

||

B : true

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Reflection is a crucial part of any easy to use serialization library and serialization ~~algorithms~~ like [JSON][16]gain in importance in the IOT era.

|

||

|

||

This is where I finish the second part of this article. I think there is a chance for the third part, more entertaining, where we connect to this board various interesting devices. If this board won’t carry them, we replace it with something a little bigger.

|

||

|

||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||

|

||

via: https://ziutek.github.io/2018/04/14/go_on_very_small_hardware2.html

|

||

|

||

作者:[Michał Derkacz ][a]

|

||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||

|

||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||

|

||

[a]:https://ziutek.github.io/

|

||

[1]:https://ziutek.github.io/2018/04/14/go_on_very_small_hardware2.html

|

||

[2]:https://ziutek.github.io/2018/03/30/go_on_very_small_hardware.html

|

||

[3]:https://golang.org/doc/effective_go.html#interfaces

|

||

[4]:https://research.swtch.com/interfaces

|

||

[5]:https://blog.golang.org/laws-of-reflection

|

||

[6]:https://github.com/texane/stlink

|

||

[7]:http://www.world-semi.com/solution/list-4-1.html

|

||

[8]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1-Wire

|

||

[9]:https://github.com/npat-efault/picocom

|

||

[10]:https://github.com/ziutek/emgo/blob/master/egpath/src/stm32/examples/f030-demo-board/usart/main.go

|

||

[11]:https://github.com/ziutek/emgo/blob/master/egpath/src/stm32/examples/f030-demo-board/morseuart/main.go

|

||

[12]:https://github.com/ziutek/emgo/blob/master/egpath/src/stm32/examples/f030-demo-board/morseled/main.go

|

||

[13]:https://blog.golang.org/laws-of-reflection

|

||

[14]:http://infocenter.arm.com/help/topic/com.arm.doc.dui0471g/Bgbjjgij.html

|

||

[15]:https://golang.org/doc/effective_go.html#type_switch

|

||

[16]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/JSON

|