28 KiB

Explore binaries using this full-featured Linux tool

Radare2 is an open source tool custom-made for binary analysis.

In 10 ways to analyze binary files on Linux, I explained how to use Linux's rich set of native tools to analyze binaries. But if you want to explore your binary further, you need a tool that is custom-made for binary analysis. If you are new to binary analysis and have mostly worked with scripting languages, 9 essential GNU binutils tools will help you get started learning the compilation process and what constitutes a binary.

Why do I need another tool?

It's natural to ask why you need yet another tool if existing Linux-native tools do similar things. Well, it's for the same reasons you use your cellphone as your alarm clock, to take notes, as a camera, to listen to music, to surf the internet, and occasionally to make and receive calls. Previously, separate devices and tools handled these functions — like a physical camera for taking pictures, a small notepad for taking notes, a bedside alarm clock to wake up, and so on. Having one device to do multiple (but related) things is convenient for the user. Also, the killer feature is interoperability between the separate functions.

Similarly, even though many Linux tools have a specific purpose, having similar (and better) functionality bundled into a single tool is very helpful. This is why I think Radare2 should be your go-to tool whenever you need to work with binaries.

Radare2 (also known as r2) is a "Unix-like reverse engineering framework and command-line toolset," according to its GitHub profile. The "2" in its name is because this version was rewritten from scratch to make it more modular.

Why Radare2?

There are tons of (non-native) Linux tools out there that are used for binary analysis, so why should you choose Radare2? My reasons are simple.

First, it's an open source project with an active and healthy community. If you are looking for slick, new features or availability of bug fixes, this matters a lot.

Second, Radare2 can be used on the command line, and it has a rich graphical user interface (GUI) environment called Cutter for those who are more comfortable with GUIs. Being a long-time Linux user, I feed more comfortable on the shell. While there is a slight learning curve to getting familiar with Radare2's commands, I would compare it to learning Vim. You learn basic things first, and once you master them, you move on to more advanced stuff. In no time, it becomes second nature.

Third, Radare2 has good support for external tools via plugins. For example, the recently open sourced Ghidra binary analysis and reversing tool is popular for its decompiler feature, which is a critical element of reversing software. You can install and use the Ghidra decompiler right from the Radare2 console, which is amazing and gives you the best of both worlds.

Get started with Radare2

To install Radare2, simply clone the repo and run the user.sh script. You might need to install some prerequisite packages if they aren't already on your system. Once the installation is complete, run the r2 -v command to see if Radare2 was installed properly:

$ git clone <https://github.com/radareorg/radare2.git>

$ cd radare2

$ sys/user.sh

# version

$ r2 -v

radare2 4.6.0-git 25266 @ linux-x86-64 git.4.4.0-930-g48047b317

commit: 48047b3171e6ed0480a71a04c3693a0650d03543 build: 2020-11-17__09:31:03

$

Get a sample test binary

Now that r2 is installed, you need a sample binary to try it out. You could use any system binary (ls, bash, and so on), but to keep things simple for this tutorial, compile the following C program:

$ cat adder.c

#include <stdio.h>

int adder(int num) {

return num + 1;

}

int main() {

int res, num1 = 100;

res = adder(num1);

printf("Number now is : %d\n", res);

return 0;

}

$

$

$ gcc adder.c -o adder

$

$ file adder

adder: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, BuildID[sha1]=9d4366f7160e1ffb46b14466e8e0d70f10de2240, not stripped

$

$ ./adder

Number now is : 101

$

Load the binary

To analyze the binary, you have to load it in Radare2. Load it by providing the file as a command line argument to the r2 command. You're dropped into a separate Radare2 console different from your shell. To exit the console, you can type Quit or Exit or hit Ctrl+D:

$ r2 ./adder

-- Learn pancake as if you were radare!

[0x004004b0]> quit

$

Analyze the binary

Before you can explore the binary, you have to ask r2 to analyze it for you. You can do that by running the aaa command in the r2 console;

$ r2 ./adder

-- Sorry, radare2 has experienced an internal error.

[0x004004b0]>

[0x004004b0]>

[0x004004b0]> aaa

[x] Analyze all flags starting with sym. and entry0 (aa)

[x] Analyze function calls (aac)

[x] Analyze len bytes of instructions for references (aar)

[x] Check for vtables

[x] Type matching analysis for all functions (aaft)

[x] Propagate noreturn information

[x] Use -AA or aaaa to perform additional experimental analysis.

[0x004004b0]>

This means that each time you pick a binary for analysis, you have to type an additional command to aaa after loading the binary. You can bypass this by calling r2 with -A followed by the binary name; this tells r2 to auto-analyze the binary for you:

$ r2 -A ./adder

[x] Analyze all flags starting with sym. and entry0 (aa)

[x] Analyze function calls (aac)

[x] Analyze len bytes of instructions for references (aar)

[x] Check for vtables

[x] Type matching analysis for all functions (aaft)

[x] Propagate noreturn information

[x] Use -AA or aaaa to perform additional experimental analysis.

-- Already up-to-date.

[0x004004b0]>

Get some basic information about the binary

Before you begin analyzing a binary, you need a starting point. In many cases, this can be the binary's file format (ELF, PE, and so on), the architecture the binary was built for (x86, AMD, ARM, and so on), and whether the binary is 32 bit or 64 bit. R2's handy iI command can provide the required information:

[0x004004b0]> iI

arch x86

baddr 0x400000

binsz 14724

bintype elf

bits 64

canary false

class ELF64

compiler GCC: (GNU) 8.3.1 20190507 (Red Hat 8.3.1-4)

crypto false

endian little

havecode true

intrp /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2

laddr 0x0

lang c

linenum true

lsyms true

machine AMD x86-64 architecture

maxopsz 16

minopsz 1

nx true

os linux

pcalign 0

pic false

relocs true

relro partial

rpath NONE

sanitiz false

static false

stripped false

subsys linux

va true

[0x004004b0]>

[0x004004b0]>

Imports and exports

Often, once you know what kind of file you are dealing with, you want to know what kind of standard library functions the binary uses or learn the program's potential functionalities. In the sample C program in this tutorial, the only library function is printf to print a message. You can see this by running the ii command, which shows all of the binary's imports:

[0x004004b0]> ii

[Imports]

nth vaddr bind type lib name

―――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

1 0x00000000 WEAK NOTYPE _ITM_deregisterTMCloneTable

2 0x004004a0 GLOBAL FUNC printf

3 0x00000000 GLOBAL FUNC __libc_start_main

4 0x00000000 WEAK NOTYPE __gmon_start__

5 0x00000000 WEAK NOTYPE _ITM_registerTMCloneTable

The binary can also have its own symbols, functions, or data. These functions are usually shown under Exports. The test binary has two functions—main and adder—that are exported. The rest of the functions are added during the compilation phase when the binary is being built. The loader needs these to load the binary (don't worry too much about them for now):

[0x004004b0]>

[0x004004b0]> iE

[Exports]

nth paddr vaddr bind type size lib name

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

82 0x00000650 0x00400650 GLOBAL FUNC 5 __libc_csu_fini

85 ---------- 0x00601024 GLOBAL NOTYPE 0 _edata

86 0x00000658 0x00400658 GLOBAL FUNC 0 _fini

89 0x00001020 0x00601020 GLOBAL NOTYPE 0 __data_start

90 0x00000596 0x00400596 GLOBAL FUNC 15 adder

92 0x00000670 0x00400670 GLOBAL OBJ 0 __dso_handle

93 0x00000668 0x00400668 GLOBAL OBJ 4 _IO_stdin_used

94 0x000005e0 0x004005e0 GLOBAL FUNC 101 __libc_csu_init

95 ---------- 0x00601028 GLOBAL NOTYPE 0 _end

96 0x000004e0 0x004004e0 GLOBAL FUNC 5 _dl_relocate_static_pie

97 0x000004b0 0x004004b0 GLOBAL FUNC 47 _start

98 ---------- 0x00601024 GLOBAL NOTYPE 0 __bss_start

99 0x000005a5 0x004005a5 GLOBAL FUNC 55 main

100 ---------- 0x00601028 GLOBAL OBJ 0 __TMC_END__

102 0x00000468 0x00400468 GLOBAL FUNC 0 _init

[0x004004b0]>

Hash info

How do you know if two binaries are similar? You can't exactly open a binary and view the source code inside it. In most cases, a binary's hash—md5sum, sha1, sha256—is used to uniquely identify it. You can find the binary hash using the it command:

[0x004004b0]> it

md5 7e6732f2b11dec4a0c7612852cede670

sha1 d5fa848c4b53021f6570dd9b18d115595a2290ae

sha256 13dd5a492219dac1443a816ef5f91db8d149e8edbf26f24539c220861769e1c2

[0x004004b0]>

Functions

Code is grouped into functions; to list which functions are present within a binary, run the afl command. The following list shows the main and adder functions. Usually, functions that start with sym.imp are imported from the standard library (glibc in this case):

[0x004004b0]> afl

0x004004b0 1 46 entry0

0x004004f0 4 41 -> 34 sym.deregister_tm_clones

0x00400520 4 57 -> 51 sym.register_tm_clones

0x00400560 3 33 -> 32 sym.__do_global_dtors_aux

0x00400590 1 6 entry.init0

0x00400650 1 5 sym.__libc_csu_fini

0x00400658 1 13 sym._fini

0x00400596 1 15 sym.adder

0x004005e0 4 101 loc..annobin_elf_init.c

0x004004e0 1 5 loc..annobin_static_reloc.c

0x004005a5 1 55 main

0x004004a0 1 6 sym.imp.printf

0x00400468 3 27 sym._init

[0x004004b0]>

Cross-references

In C, the main function is where a program starts its execution. Ideally, other functions are called from main and, upon exiting a program, the main function returns an exit status to the operating system. This is evident in the source code; however, what about a binary? How can you tell where the adder function is called?

You can use the axt command followed by the function name to see where the adder function is called; as you can see below, it is called from the main function. This is known as cross-referencing. But what calls the main function itself? The axt main function below shows that it is called by entry0 (I'll leave learning about entry0 as an exercise for the reader):

[0x004004b0]> axt sym.adder

main 0x4005b9 [CALL] call sym.adder

[0x004004b0]>

[0x004004b0]> axt main

entry0 0x4004d1 [DATA] mov rdi, main

[0x004004b0]>

Seek locations

When working with text files, you often move within a file by referencing a line number followed by a row or a column number; in a binary, you use addresses. These are hexadecimal numbers starting with 0x followed by an address. To find where you are in a binary, run the s command. To move to a different location, use the s command followed by the address.

Function names are like labels, which are represented by addresses internally. If the function name is in the binary (not stripped), you can use the s command followed by the function name to jump to a specific function address. Similarly, if you want to jump to the start of the binary, type s 0:

[0x004004b0]> s

0x4004b0

[0x004004b0]>

[0x004004b0]> s main

[0x004005a5]>

[0x004005a5]> s

0x4005a5

[0x004005a5]>

[0x004005a5]> s sym.adder

[0x00400596]>

[0x00400596]> s

0x400596

[0x00400596]>

[0x00400596]> s 0

[0x00000000]>

[0x00000000]> s

0x0

[0x00000000]>

Hexadecimal view

Oftentimes, the raw binary doesn't make sense. It can help to view the binary in hexadecimal mode alongside its equivalent ASCII representation:

[0x004004b0]> s main

[0x004005a5]>

[0x004005a5]> px

\- offset - 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0123456789ABCDEF

0x004005a5 5548 89e5 4883 ec10 c745 fc64 0000 008b UH..H....E.d....

0x004005b5 45fc 89c7 e8d8 ffff ff89 45f8 8b45 f889 E.........E..E..

0x004005c5 c6bf 7806 4000 b800 0000 00e8 cbfe ffff ..x.@...........

0x004005d5 b800 0000 00c9 c30f 1f40 00f3 0f1e fa41 .........@.....A

0x004005e5 5749 89d7 4156 4989 f641 5541 89fd 4154 WI..AVI..AUA..AT

0x004005f5 4c8d 2504 0820 0055 488d 2d04 0820 0053 L.%.. .UH.-.. .S

0x00400605 4c29 e548 83ec 08e8 57fe ffff 48c1 fd03 L).H....W...H...

0x00400615 741f 31db 0f1f 8000 0000 004c 89fa 4c89 t.1........L..L.

0x00400625 f644 89ef 41ff 14dc 4883 c301 4839 dd75 .D..A...H...H9.u

0x00400635 ea48 83c4 085b 5d41 5c41 5d41 5e41 5fc3 .H...[]A\A]A^A_.

0x00400645 9066 2e0f 1f84 0000 0000 00f3 0f1e fac3 .f..............

0x00400655 0000 00f3 0f1e fa48 83ec 0848 83c4 08c3 .......H...H....

0x00400665 0000 0001 0002 0000 0000 0000 0000 0000 ................

0x00400675 0000 004e 756d 6265 7220 6e6f 7720 6973 ...Number now is

0x00400685 2020 3a20 2564 0a00 0000 0001 1b03 3b44 : %d........;D

0x00400695 0000 0007 0000 0000 feff ff88 0000 0020 ...............

[0x004005a5]>

Disassembly

If you are working with compiled binaries, there is no source code you can view. The compiler translates the source code into machine language instructions that the CPU can understand and execute; the result is the binary or executable. However, you can view assembly instructions (mnemonics) to make sense of what the program is doing. For example, if you want to see what the main function is doing, you can seek the address of the main function using s main and then run the pdf command to view the disassembly instructions.

To understand the assembly instructions, you need to refer to the architecture manual (x86 in this case), its application binary interface (its ABI, or calling conventions), and have a basic understanding of how the stack works:

[0x004004b0]> s main

[0x004005a5]>

[0x004005a5]> s

0x4005a5

[0x004005a5]>

[0x004005a5]> pdf

; DATA XREF from entry0 @ 0x4004d1

┌ 55: int main (int argc, char **argv, char **envp);

│ ; var int64_t var_8h @ rbp-0x8

│ ; var int64_t var_4h @ rbp-0x4

│ 0x004005a5 55 push rbp

│ 0x004005a6 4889e5 mov rbp, rsp

│ 0x004005a9 4883ec10 sub rsp, 0x10

│ 0x004005ad c745fc640000. mov dword [var_4h], 0x64 ; 'd' ; 100

│ 0x004005b4 8b45fc mov eax, dword [var_4h]

│ 0x004005b7 89c7 mov edi, eax

│ 0x004005b9 e8d8ffffff call sym.adder

│ 0x004005be 8945f8 mov dword [var_8h], eax

│ 0x004005c1 8b45f8 mov eax, dword [var_8h]

│ 0x004005c4 89c6 mov esi, eax

│ 0x004005c6 bf78064000 mov edi, str.Number_now_is__:__d ; 0x400678 ; "Number now is : %d\n" ; const char *format

│ 0x004005cb b800000000 mov eax, 0

│ 0x004005d0 e8cbfeffff call sym.imp.printf ; int printf(const char *format)

│ 0x004005d5 b800000000 mov eax, 0

│ 0x004005da c9 leave

└ 0x004005db c3 ret

[0x004005a5]>

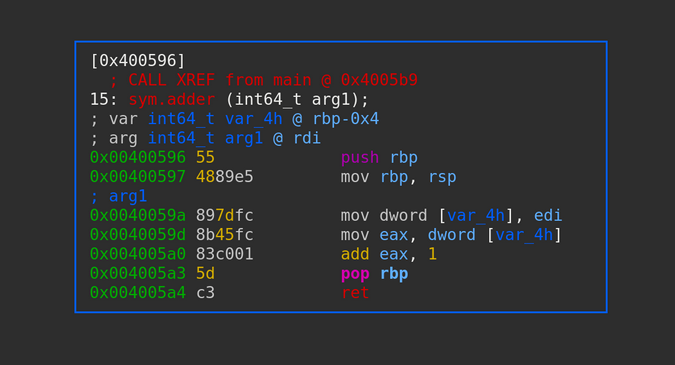

Here is the disassembly for the adder function:

[0x004005a5]> s sym.adder

[0x00400596]>

[0x00400596]> s

0x400596

[0x00400596]>

[0x00400596]> pdf

; CALL XREF from main @ 0x4005b9

┌ 15: sym.adder (int64_t arg1);

│ ; var int64_t var_4h @ rbp-0x4

│ ; arg int64_t arg1 @ rdi

│ 0x00400596 55 push rbp

│ 0x00400597 4889e5 mov rbp, rsp

│ 0x0040059a 897dfc mov dword [var_4h], edi ; arg1

│ 0x0040059d 8b45fc mov eax, dword [var_4h]

│ 0x004005a0 83c001 add eax, 1

│ 0x004005a3 5d pop rbp

└ 0x004005a4 c3 ret

[0x00400596]>

Strings

Seeing which strings are present within the binary can be a starting point to binary analysis. Strings are hardcoded into a binary and often provide important hints to shift your focus to analyze certain areas. Run the iz command within the binary to list all the strings. The test binary has only one string hardcoded in the binary:

[0x004004b0]> iz

[Strings]

nth paddr vaddr len size section type string

―――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

0 0x00000678 0x00400678 20 21 .rodata ascii Number now is : %d\n

[0x004004b0]>

Cross-reference strings

As with functions, you can cross-reference strings to see where they are being printed from and understand the code around them:

[0x004004b0]> ps @ 0x400678

Number now is : %d

[0x004004b0]>

[0x004004b0]> axt 0x400678

main 0x4005c6 [DATA] mov edi, str.Number_now_is__:__d

[0x004004b0]>

Visual mode

When your code is complicated with multiple functions called, it's easy to get lost. It can be helpful to have a graphic or visual view of which functions are called, which paths are taken based on certain conditions, etc. You can explore r2's visual mode by using the VV command after moving to a function of interest. For example, for the adder function:

[0x004004b0]> s sym.adder

[0x00400596]>

[0x00400596]> VV

(Gaurav Kamathe, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Debugger

So far, you have been doing static analysis—you are just looking at things in the binary without running it. Sometimes you need to execute the binary and analyze various information in memory at runtime. r2's internal debugger allows you to run a binary, put in breakpoints, analyze variables' values, or dump registers' contents.

Start the debugger with the -d flag, and add the -A flag to do an analysis as the binary loads. You can set breakpoints at various places, like functions or memory addresses, by using the db <function-name> command. To view existing breakpoints, use the dbi command. Once you have placed your breakpoints, start running the binary using the dc command. You can view the stack using the dbt command, which shows function calls. Finally, you can dump the contents of the registers using the drr command:

$ r2 -d -A ./adder

Process with PID 17453 started...

= attach 17453 17453

bin.baddr 0x00400000

Using 0x400000

asm.bits 64

[x] Analyze all flags starting with sym. and entry0 (aa)

[x] Analyze function calls (aac)

[x] Analyze len bytes of instructions for references (aar)

[x] Check for vtables

[x] Type matching analysis for all functions (aaft)

[x] Propagate noreturn information

[x] Use -AA or aaaa to perform additional experimental analysis.

-- git checkout hamster

[0x7f77b0a28030]>

[0x7f77b0a28030]> db main

[0x7f77b0a28030]>

[0x7f77b0a28030]> db sym.adder

[0x7f77b0a28030]>

[0x7f77b0a28030]> dbi

0 0x004005a5 E:1 T:0

1 0x00400596 E:1 T:0

[0x7f77b0a28030]>

[0x7f77b0a28030]> afl | grep main

0x004005a5 1 55 main

[0x7f77b0a28030]>

[0x7f77b0a28030]> afl | grep sym.adder

0x00400596 1 15 sym.adder

[0x7f77b0a28030]>

[0x7f77b0a28030]> dc

hit breakpoint at: 0x4005a5

[0x004005a5]>

[0x004005a5]> dbt

0 0x4005a5 sp: 0x0 0 [main] main sym.adder+15

1 0x7f77b0687873 sp: 0x7ffe35ff6858 0 [??] section..gnu.build.attributes-1345820597

2 0x7f77b0a36e0a sp: 0x7ffe35ff68e8 144 [??] map.usr_lib64_ld_2.28.so.r_x+65034

[0x004005a5]> dc

hit breakpoint at: 0x400596

[0x00400596]> dbt

0 0x400596 sp: 0x0 0 [sym.adder] rip entry.init0+6

1 0x4005be sp: 0x7ffe35ff6838 0 [main] main+25

2 0x7f77b0687873 sp: 0x7ffe35ff6858 32 [??] section..gnu.build.attributes-1345820597

3 0x7f77b0a36e0a sp: 0x7ffe35ff68e8 144 [??] map.usr_lib64_ld_2.28.so.r_x+65034

[0x00400596]>

[0x00400596]>

[0x00400596]> dr

rax = 0x00000064

rbx = 0x00000000

rcx = 0x7f77b0a21738

rdx = 0x7ffe35ff6948

r8 = 0x7f77b0a22da0

r9 = 0x7f77b0a22da0

r10 = 0x0000000f

r11 = 0x00000002

r12 = 0x004004b0

r13 = 0x7ffe35ff6930

r14 = 0x00000000

r15 = 0x00000000

rsi = 0x7ffe35ff6938

rdi = 0x00000064

rsp = 0x7ffe35ff6838

rbp = 0x7ffe35ff6850

rip = 0x00400596

rflags = 0x00000202

orax = 0xffffffffffffffff

[0x00400596]>

Decompiler

Being able to understand assembly is a prerequisite to binary analysis. Assembly language is always tied to the architecture the binary is built on and is supposed to run on. There is never a 1:1 mapping between a line of source code and assembly code. Often, a single line of C source code produces multiple lines of assembly. So, reading assembly code line-by-line is not optimal.

This is where decompilers come in. They try to reconstruct the possible source code based on the assembly instructions. This is NEVER exactly the same as the source code used to create the binary; it is a close representation of the source based on assembly. Also, take into account that compiler optimizations that generate different assembly code to speed things up, reduce the size of a binary, etc., will make the decompiler's job more difficult. Also, malware authors often deliberately obfuscate code to put a malware analyst off.

Radare2 provides decompilers through plugins. You can install any decompiler that is supported by Radare2. View current plugins with the r2pm -l command. Install a sample r2dec decompiler with the r2pm install command:

$ r2pm -l

$

$ r2pm install r2dec

Cloning into 'r2dec'...

remote: Enumerating objects: 100, done.

remote: Counting objects: 100% (100/100), done.

remote: Compressing objects: 100% (97/97), done.

remote: Total 100 (delta 18), reused 27 (delta 1), pack-reused 0

Receiving objects: 100% (100/100), 1.01 MiB | 1.31 MiB/s, done.

Resolving deltas: 100% (18/18), done.

Install Done For r2dec

gmake: Entering directory '/root/.local/share/radare2/r2pm/git/r2dec/p'

[CC] duktape/duktape.o

[CC] duktape/duk_console.o

[CC] core_pdd.o

[CC] core_pdd.so

gmake: Leaving directory '/root/.local/share/radare2/r2pm/git/r2dec/p'

$

$ r2pm -l

r2dec

$

Decompiler view

To decompile a binary, load the binary in r2 and auto-analyze it. Move to the function of interest—adder in this example—using the s sym.adder command, then use the pdda command to view the assembly and decompiled source code side-by-side. Reading this decompiled source code is often easier than reading assembly line-by-line:

$ r2 -A ./adder

[x] Analyze all flags starting with sym. and entry0 (aa)

[x] Analyze function calls (aac)

[x] Analyze len bytes of instructions for references (aar)

[x] Check for vtables

[x] Type matching analysis for all functions (aaft)

[x] Propagate noreturn information

[x] Use -AA or aaaa to perform additional experimental analysis.

-- What do you want to debug today?

[0x004004b0]>

[0x004004b0]> s sym.adder

[0x00400596]>

[0x00400596]> s

0x400596

[0x00400596]>

[0x00400596]> pdda

; assembly | /* r2dec pseudo code output */

| /* ./adder @ 0x400596 */

| #include <stdint.h>

|

; (fcn) sym.adder () | int32_t adder (int64_t arg1) {

| int64_t var_4h;

| rdi = arg1;

0x00400596 push rbp |

0x00400597 mov rbp, rsp |

0x0040059a mov dword [rbp - 4], edi | *((rbp - 4)) = edi;

0x0040059d mov eax, dword [rbp - 4] | eax = *((rbp - 4));

0x004005a0 add eax, 1 | eax++;

0x004005a3 pop rbp |

0x004005a4 ret | return eax;

| }

[0x00400596]>

Configure settings

As you get more comfortable with Radare2, you will want to change its configuration to tune it to how you work. You can view r2's default configurations using the e command. To set a specific configuration, add config = value after the e command:

[0x004005a5]> e | wc -l

593

[0x004005a5]> e | grep syntax

asm.syntax = intel

[0x004005a5]>

[0x004005a5]> e asm.syntax = att

[0x004005a5]>

[0x004005a5]> e | grep syntax

asm.syntax = att

[0x004005a5]>

To make the configuration changes permanent, place them in a startup file named .radare2rc that r2 reads at startup. This file is usually found in your home directory; if not, you can create one. Some sample configuration options include:

$ cat ~/.radare2rc

e asm.syntax = att

e scr.utf8 = true

eco solarized

e cmd.stack = true

e stack.size = 256

$

Explore more

You've seen enough Radare2 features to find your way around the tool. Because Radare2 follows the Unix philosophy, even though you can do various things from its console, it uses a separate set of binaries underneath to do its tasks.

Explore the standalone binaries listed below to see how they work. For example, the binary information seen in the console with the iI command can also be found using the rabin2 <binary> command:

$ cd bin/

$

$ ls

prefix r2agent r2pm rabin2 radiff2 ragg2 rarun2 rasm2

r2 r2-indent r2r radare2 rafind2 rahash2 rasign2 rax2

$

What do you think about Radare2? Share your feedback in the comments.

via: https://opensource.com/article/21/1/linux-radare2

作者:Gaurav Kamathe 选题:lujun9972 译者:译者ID 校对:校对者ID