mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2024-12-26 21:30:55 +08:00

276 lines

12 KiB

Markdown

276 lines

12 KiB

Markdown

What's a hero without a villain? How to add one to your Python game

|

||

======

|

||

|

||

|

||

In the previous articles in this series (see [part 1][1], [part 2][2], [part 3][3], and [part 4][4]), you learned how to use Pygame and Python to spawn a playable character in an as-yet empty video game world. But, what's a hero without a villain?

|

||

|

||

It would make for a pretty boring game if you had no enemies, so in this article, you'll add an enemy to your game and construct a framework for building levels.

|

||

|

||

It might seem strange to jump ahead to enemies when there's still more to be done to make the player sprite fully functional, but you've learned a lot already, and creating villains is very similar to creating a player sprite. So relax, use the knowledge you already have, and see what it takes to stir up some trouble.

|

||

|

||

For this exercise, you can download some pre-built assets from [Open Game Art][5]. Here are some of the assets I use:

|

||

|

||

|

||

+ Inca tileset

|

||

+ Some invaders

|

||

+ Sprites, characters, objects, and effects

|

||

|

||

|

||

### Creating the enemy sprite

|

||

|

||

Yes, whether you realize it or not, you basically already know how to implement enemies. The process is very similar to creating a player sprite:

|

||

|

||

1. Make a class so enemies can spawn.

|

||

2. Create an `update` function so enemies can detect collisions.

|

||

3. Create a `move` function so your enemy can roam around.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Start with the class. Conceptually, it's mostly the same as your Player class. You set an image or series of images, and you set the sprite's starting position.

|

||

|

||

Before continuing, make sure you have a graphic for your enemy, even if it's just a temporary one. Place the graphic in your game project's `images` directory (the same directory where you placed your player image).

|

||

|

||

A game looks a lot better if everything alive is animated. Animating an enemy sprite is done the same way as animating a player sprite. For now, though, keep it simple, and use a non-animated sprite.

|

||

|

||

At the top of the `objects` section of your code, create a class called Enemy with this code:

|

||

```

|

||

class Enemy(pygame.sprite.Sprite):

|

||

|

||

'''

|

||

|

||

Spawn an enemy

|

||

|

||

'''

|

||

|

||

def __init__(self,x,y,img):

|

||

|

||

pygame.sprite.Sprite.__init__(self)

|

||

|

||

self.image = pygame.image.load(os.path.join('images',img))

|

||

|

||

self.image.convert_alpha()

|

||

|

||

self.image.set_colorkey(ALPHA)

|

||

|

||

self.rect = self.image.get_rect()

|

||

|

||

self.rect.x = x

|

||

|

||

self.rect.y = y

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

If you want to animate your enemy, do it the [same way][4] you animated your player.

|

||

|

||

### Spawning an enemy

|

||

|

||

You can make the class useful for spawning more than just one enemy by allowing yourself to tell the class which image to use for the sprite and where in the world the sprite should appear. This means you can use this same enemy class to generate any number of enemy sprites anywhere in the game world. All you have to do is make a call to the class, and tell it which image to use and the X and Y coordinates of your desired spawn point.

|

||

|

||

Again, this is similar in principle to spawning a player sprite. In the `setup` section of your script, add this code:

|

||

```

|

||

enemy = Enemy(20,200,'yeti.png')# spawn enemy

|

||

|

||

enemy_list = pygame.sprite.Group() # create enemy group

|

||

|

||

enemy_list.add(enemy) # add enemy to group

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

In that sample code, `20` is the X position and `200` is the Y position. You might need to adjust these numbers, depending on how big your enemy sprite is, but try to get it to spawn in a place so that you can reach it with your player sprite. `Yeti.png` is the image used for the enemy.

|

||

|

||

Next, draw all enemies in the enemy group to the screen. Right now, you have only one enemy, but you can add more later if you want. As long as you add an enemy to the enemies group, it will be drawn to the screen during the main loop. The middle line is the new line you need to add:

|

||

```

|

||

player_list.draw(world)

|

||

|

||

enemy_list.draw(world) # refresh enemies

|

||

|

||

pygame.display.flip()

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

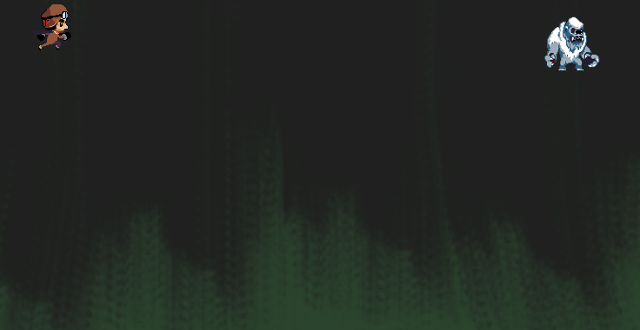

Launch your game. Your enemy appears in the game world at whatever X and Y coordinate you chose.

|

||

|

||

### Level one

|

||

|

||

Your game is in its infancy, but you will probably want to add another level. It's important to plan ahead when you program so your game can grow as you learn more about programming. Even though you don't even have one complete level yet, you should code as if you plan on having many levels.

|

||

|

||

Think about what a "level" is. How do you know you are at a certain level in a game?

|

||

|

||

You can think of a level as a collection of items. In a platformer, such as the one you are building here, a level consists of a specific arrangement of platforms, placement of enemies and loot, and so on. You can build a class that builds a level around your player. Eventually, when you create more than one level, you can use this class to generate the next level when your player reaches a specific goal.

|

||

|

||

Move the code you wrote to create an enemy and its group into a new function that will be called along with each new level. It requires some modification so that each time you create a new level, you can create several enemies:

|

||

```

|

||

class Level():

|

||

|

||

def bad(lvl,eloc):

|

||

|

||

if lvl == 1:

|

||

|

||

enemy = Enemy(eloc[0],eloc[1],'yeti.png') # spawn enemy

|

||

|

||

enemy_list = pygame.sprite.Group() # create enemy group

|

||

|

||

enemy_list.add(enemy) # add enemy to group

|

||

|

||

if lvl == 2:

|

||

|

||

print("Level " + str(lvl) )

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

return enemy_list

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The `return` statement ensures that when you use the `Level.bad` function, you're left with an `enemy_list` containing each enemy you defined.

|

||

|

||

Since you are creating enemies as part of each level now, your `setup` section needs to change, too. Instead of creating an enemy, you must define where the enemy will spawn and what level it belongs to.

|

||

```

|

||

eloc = []

|

||

|

||

eloc = [200,20]

|

||

|

||

enemy_list = Level.bad( 1, eloc )

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Run the game again to confirm your level is generating correctly. You should see your player, as usual, and the enemy you added in this chapter.

|

||

|

||

### Hitting the enemy

|

||

|

||

An enemy isn't much of an enemy if it has no effect on the player. It's common for enemies to cause damage when a player collides with them.

|

||

|

||

Since you probably want to track the player's health, the collision check happens in the Player class rather than in the Enemy class. You can track the enemy's health, too, if you want. The logic and code are pretty much the same, but, for now, just track the player's health.

|

||

|

||

To track player health, you must first establish a variable for the player's health. The first line in this code sample is for context, so add the second line to your Player class:

|

||

```

|

||

self.frame = 0

|

||

|

||

self.health = 10

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

In the `update` function of your Player class, add this code block:

|

||

```

|

||

hit_list = pygame.sprite.spritecollide(self, enemy_list, False)

|

||

|

||

for enemy in hit_list:

|

||

|

||

self.health -= 1

|

||

|

||

print(self.health)

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

This code establishes a collision detector using the Pygame function `sprite.spritecollide`, called `enemy_hit`. This collision detector sends out a signal any time the hitbox of its parent sprite (the player sprite, where this detector has been created) touches the hitbox of any sprite in `enemy_list`. The `for` loop is triggered when such a signal is received and deducts a point from the player's health.

|

||

|

||

Since this code appears in the `update` function of your player class and `update` is called in your main loop, Pygame checks for this collision once every clock tick.

|

||

|

||

### Moving the enemy

|

||

|

||

An enemy that stands still is useful if you want, for instance, spikes or traps that can harm your player, but the game is more of a challenge if the enemies move around a little.

|

||

|

||

Unlike a player sprite, the enemy sprite is not controlled by the user. Its movements must be automated.

|

||

|

||

Eventually, your game world will scroll, so how do you get an enemy to move back and forth within the game world when the game world itself is moving?

|

||

|

||

You tell your enemy sprite to take, for example, 10 paces to the right, then 10 paces to the left. An enemy sprite can't count, so you have to create a variable to keep track of how many paces your enemy has moved and program your enemy to move either right or left depending on the value of your counting variable.

|

||

|

||

First, create the counter variable in your Enemy class. Add the last line in this code sample:

|

||

```

|

||

self.rect = self.image.get_rect()

|

||

|

||

self.rect.x = x

|

||

|

||

self.rect.y = y

|

||

|

||

self.counter = 0 # counter variable

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Next, create a `move` function in your Enemy class. Use an if-else loop to create what is called an infinite loop:

|

||

|

||

* Move right if the counter is on any number from 0 to 100.

|

||

* Move left if the counter is on any number from 100 to 200.

|

||

* Reset the counter back to 0 if the counter is greater than 200.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

An infinite loop has no end; it loops forever because nothing in the loop is ever untrue. The counter, in this case, is always either between 0 and 100 or 100 and 200, so the enemy sprite walks right to left and right to left forever.

|

||

|

||

The actual numbers you use for how far the enemy will move in either direction depending on your screen size, and possibly, eventually, the size of the platform your enemy is walking on. Start small and work your way up as you get used to the results. Try this first:

|

||

```

|

||

def move(self):

|

||

|

||

'''

|

||

|

||

enemy movement

|

||

|

||

'''

|

||

|

||

distance = 80

|

||

|

||

speed = 8

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

if self.counter >= 0 and self.counter <= distance:

|

||

|

||

self.rect.x += speed

|

||

|

||

elif self.counter >= distance and self.counter <= distance*2:

|

||

|

||

self.rect.x -= speed

|

||

|

||

else:

|

||

|

||

self.counter = 0

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

self.counter += 1

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

You can adjust the distance and speed as needed.

|

||

|

||

Will this code work if you launch your game now?

|

||

|

||

Of course not, and you probably know why. You must call the `move` function in your main loop. The first line in this sample code is for context, so add the last two lines:

|

||

```

|

||

enemy_list.draw(world) #refresh enemy

|

||

|

||

for e in enemy_list:

|

||

|

||

e.move()

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Launch your game and see what happens when you hit your enemy. You might have to adjust where the sprites spawn so that your player and your enemy sprite can collide. When they do collide, look in the console of [IDLE][6] or [Ninja-IDE][7] to see the health points being deducted.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

You may notice that health is deducted for every moment your player and enemy are touching. That's a problem, but it's a problem you'll solve later, after you've had more practice with Python.

|

||

|

||

For now, try adding some more enemies. Remember to add each enemy to the `enemy_list`. As an exercise, see if you can think of how you can change how far different enemy sprites move.

|

||

|

||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||

|

||

via: https://opensource.com/article/18/5/pygame-enemy

|

||

|

||

作者:[Seth Kenlon][a]

|

||

选题:[lujun9972](https://github.com/lujun9972)

|

||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||

|

||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||

|

||

[a]: https://opensource.com/users/seth

|

||

[1]:https://opensource.com/article/17/10/python-101

|

||

[2]:https://opensource.com/article/17/12/game-framework-python

|

||

[3]:https://opensource.com/article/17/12/game-python-add-a-player

|

||

[4]:https://opensource.com/article/17/12/game-python-moving-player

|

||

[5]:https://opengameart.org

|

||

[6]:https://docs.python.org/3/library/idle.html

|

||

[7]:http://ninja-ide.org/

|