mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-01-22 23:00:57 +08:00

217 lines

13 KiB

Markdown

217 lines

13 KiB

Markdown

[Concurrent Servers: Part 1 - Introduction][18]

|

||

============================================================

|

||

|

||

GitFuture is Translating

|

||

|

||

This is the first post in a series about concurrent network servers. My plan is to examine several popular concurrency models for network servers that handle multiple clients simultaneously, and judge those models on scalability and ease of implementation. All servers will listen for socket connections and implement a simple protocol to interact with clients.

|

||

|

||

All posts in the series:

|

||

|

||

* [Part 1 - Introduction][7]

|

||

|

||

* [Part 2 - Threads][8]

|

||

|

||

* [Part 3 - Event-driven][9]

|

||

|

||

### The protocol

|

||

|

||

The protocol used throughout this series is very simple, but should be sufficient to demonstrate many interesting aspects of concurrent server design. Notably, the protocol is _stateful_ - the server changes internal state based on the data clients send, and its behavior depends on that internal state. Not all protocols all stateful - in fact, many protocols over HTTP these days are stateless - but stateful protocols are sufficiently common to warrant a serious discussion.

|

||

|

||

Here's the protocol, from the server's point of view:

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

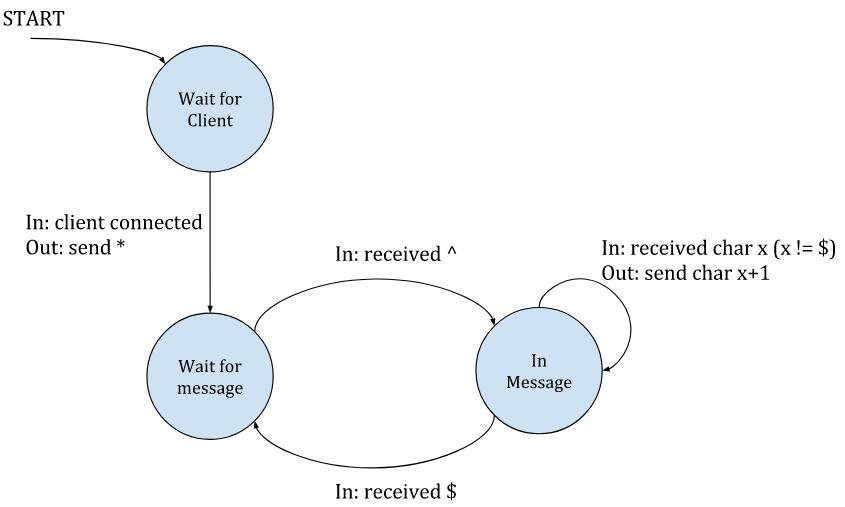

In words: the server waits for a new client to connect; when a client connects, the server sends it a `*` character and enters a "wait for message state". In this state, the server ignores everything the client sends until it sees a `^` character that signals that a new message begins. At this point it moves to the "in message" state, where it echoes back everything the client sends, incrementing each byte [[1]][10]. When the client sends a `$`, the server goes back to waiting for a new message. The `^` and `$` characters are only used to delimit messages - they are not echoed back.

|

||

|

||

An implicit arrow exists from each state back to the "wait for client" state, in case the client disconnects. By corollary, the only way for a client to signal "I'm done" is to simply close its side of the connection.

|

||

|

||

Obviously, this protocol is a simplification of more realistic protocols that have complicated headers, escape sequences (to support `$` inside a message body, for example) and additional state transitions, but for our goals this will do just fine.

|

||

|

||

Another note: this series is introductory, and assumes clients are generally well behaved (albeit potentially slow); therefore there are no timeouts and no special provisions made to ensure that the server doesn't end up being blocked indefinitely by rogue (or buggy) clients.

|

||

|

||

### A sequential server

|

||

|

||

Our first server in this series is a simple "sequential" server, written in C without using any libraries beyond standard POSIX fare for sockets. The server is sequential because it can only handle a single client at any given time; when a client connects, the server enters the state machine shown above and won't even listen on the socket for new clients until the current client is done. Obviously this isn't concurrent and doesn't scale beyond very light loads, but it's helpful to discuss since we need a simple-to-understand baseline.

|

||

|

||

The full code for this server [is here][11]; in what follows, I'll focus on some highlights. The outer loop in `main` listens on the socket for new clients to connect. Once a client connects, it calls `serve_connection` which runs through the protocol until the client disconnects.

|

||

|

||

To accept new connections, the sequential server calls `accept` on a listening socket in a loop:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

while (1) {

|

||

struct sockaddr_in peer_addr;

|

||

socklen_t peer_addr_len = sizeof(peer_addr);

|

||

|

||

int newsockfd =

|

||

accept(sockfd, (struct sockaddr*)&peer_addr, &peer_addr_len);

|

||

|

||

if (newsockfd < 0) {

|

||

perror_die("ERROR on accept");

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

report_peer_connected(&peer_addr, peer_addr_len);

|

||

serve_connection(newsockfd);

|

||

printf("peer done\n");

|

||

}

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Each time `accept` returns a new connected socket, the server calls `serve_connection`; note that this is a _blocking_ call - until `serve_connection` returns, `accept` is not called again; the server blocks until one client is done before accepting a new client. In other words, clients are serviced _sequentially_ .

|

||

|

||

Here's `serve_connection`:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

typedef enum { WAIT_FOR_MSG, IN_MSG } ProcessingState;

|

||

|

||

void serve_connection(int sockfd) {

|

||

if (send(sockfd, "*", 1, 0) < 1) {

|

||

perror_die("send");

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

ProcessingState state = WAIT_FOR_MSG;

|

||

|

||

while (1) {

|

||

uint8_t buf[1024];

|

||

int len = recv(sockfd, buf, sizeof buf, 0);

|

||

if (len < 0) {

|

||

perror_die("recv");

|

||

} else if (len == 0) {

|

||

break;

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

for (int i = 0; i < len; ++i) {

|

||

switch (state) {

|

||

case WAIT_FOR_MSG:

|

||

if (buf[i] == '^') {

|

||

state = IN_MSG;

|

||

}

|

||

break;

|

||

case IN_MSG:

|

||

if (buf[i] == '$') {

|

||

state = WAIT_FOR_MSG;

|

||

} else {

|

||

buf[i] += 1;

|

||

if (send(sockfd, &buf[i], 1, 0) < 1) {

|

||

perror("send error");

|

||

close(sockfd);

|

||

return;

|

||

}

|

||

}

|

||

break;

|

||

}

|

||

}

|

||

}

|

||

|

||

close(sockfd);

|

||

}

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

It pretty much follows the protocol state machine. Each time around the loop, the server attempts to receive data from the client. Receiving 0 bytes means the client disconnected, and the loop exits. Otherwise, the received buffer is examined byte by byte, and each byte can potentially trigger a state change.

|

||

|

||

The number of bytes `recv` returns is completely independent of the number of messages (`^...$` enclosed sequences of bytes) the client sends. Therefore, it's important to go through the whole buffer in a state-keeping loop. Critically, each received buffer may contain multiple messages, but also the start of a new message without its actual ending; the ending can arrive in the next buffer, which is why the processing state is maintained across loop iterations.

|

||

|

||

For example, suppose the `recv` function in the main loop returned non-empty buffers three times for some connection:

|

||

|

||

1. `^abc$de^abte$f`

|

||

|

||

2. `xyz^123`

|

||

|

||

3. `25$^ab$abab`

|

||

|

||

What data is the server sending back? Tracing the code manually is very useful to understand the state transitions (for the answer see [[2]][12]).

|

||

|

||

### Multiple concurrent clients

|

||

|

||

What happens when multiple clients attempt to connect to the sequential server at roughly the same time?

|

||

|

||

The server's code (and its name - `sequential-server`) make it clear that clients are only handled _one at a time_ . As long as the server is busy dealing with a client in `serve_connection`, it doesn't accept new client connections. Only when the current client disconnects does `serve_connection` return and the outer-most loop may accept new client connections.

|

||

|

||

To show this in action, [the sample code for this series][13] includes a Python script that simulates several clients trying to connect at the same time. Each client sends the three buffers shown above [[3]][14], with some delays between them.

|

||

|

||

The client script runs the clients concurrently in separate threads. Here's a transcript of the client's interaction with our sequential server:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

$ python3.6 simple-client.py -n 3 localhost 9090

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:17,763:conn1 connected...

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:17,763:conn1 sending b'^abc$de^abte$f'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:17,763:conn1 received b'b'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:17,802:conn1 received b'cdbcuf'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:18,764:conn1 sending b'xyz^123'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:18,764:conn1 received b'234'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:19,764:conn1 sending b'25$^ab0000$abab'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:19,765:conn1 received b'36bc1111'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:19,965:conn1 disconnecting

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:19,966:conn2 connected...

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:19,967:conn2 sending b'^abc$de^abte$f'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:19,967:conn2 received b'b'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:20,006:conn2 received b'cdbcuf'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:20,968:conn2 sending b'xyz^123'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:20,969:conn2 received b'234'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:21,970:conn2 sending b'25$^ab0000$abab'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:21,970:conn2 received b'36bc1111'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:22,171:conn2 disconnecting

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:22,171:conn0 connected...

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:22,172:conn0 sending b'^abc$de^abte$f'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:22,172:conn0 received b'b'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:22,210:conn0 received b'cdbcuf'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:23,173:conn0 sending b'xyz^123'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:23,174:conn0 received b'234'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:24,175:conn0 sending b'25$^ab0000$abab'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:24,176:conn0 received b'36bc1111'

|

||

INFO:2017-09-16 14:14:24,376:conn0 disconnecting

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The thing to note here is the connection name: `conn1` managed to get through to the server first, and interacted with it for a while. The next connection - `conn2` - only got through after the first one disconnected, and so on for the third connection. As the logs show, each connection is keeping the server busy for ~2.2 seconds (which is exactly what the artificial delays in the client code add up to), and during this time no other client can connect.

|

||

|

||

Clearly, this is not a scalable strategy. In our case, the client incurs the delay leaving the server completely idle for most of the interaction. A smarter server could handle dozens of other clients while the original one is busy on its end (and we'll see how to achieve that later in the series). Even if the delay is on the server side, this delay is often something that doesn't really keep the CPU too busy; for example, looking up information in a database (which is mostly network waiting time for a database server, or disk lookup time for local databases).

|

||

|

||

### Summary and next steps

|

||

|

||

The goal of presenting this simple sequential server is twofold:

|

||

|

||

1. Introduce the problem domain and some basics of socket programming used throughout the series.

|

||

|

||

2. Provide motivation for concurrent serving - as the previous section demonstrates, the sequential server doesn't scale beyond very trivial loads and is not an efficient way of using resources, in general.

|

||

|

||

Before reading the next posts in the series, make sure you understand the server/client protocol described here and the code for the sequential server. I've written about such simple protocols before; for example,[framing in serial communications][15] and [co-routines as alternatives to state machines][16]. For basics of network programming with sockets, [Beej's guide][17] is not a bad starting point, but for a deeper understanding I'd recommend a book.

|

||

|

||

If anything remains unclear, please let me know in comments or by email. On to concurrent servers!

|

||

|

||

* * *

|

||

|

||

|

||

[[1]][1] The In/Out notation on state transitions denotes a [Mealy machine][2].

|

||

|

||

[[2]][3] The answer is `bcdbcuf23436bc`.

|

||

|

||

[[3]][4] With a small difference of an added string of `0000` at the end - the server's answer to this sequence is a signal for the client to disconnect; it's a simplistic handshake that ensures the client had time to receive all of the server's reply.

|

||

|

||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||

|

||

via: https://eli.thegreenplace.net/2017/concurrent-servers-part-1-introduction/

|

||

|

||

作者:[Eli Bendersky][a]

|

||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||

|

||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||

|

||

[a]:https://eli.thegreenplace.net/pages/about

|

||

[1]:https://eli.thegreenplace.net/2017/concurrent-servers-part-1-introduction/#id1

|

||

[2]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mealy_machine

|

||

[3]:https://eli.thegreenplace.net/2017/concurrent-servers-part-1-introduction/#id2

|

||

[4]:https://eli.thegreenplace.net/2017/concurrent-servers-part-1-introduction/#id3

|

||

[5]:https://eli.thegreenplace.net/tag/concurrency

|

||

[6]:https://eli.thegreenplace.net/tag/c-c

|

||

[7]:http://eli.thegreenplace.net/2017/concurrent-servers-part-1-introduction/

|

||

[8]:http://eli.thegreenplace.net/2017/concurrent-servers-part-2-threads/

|

||

[9]:http://eli.thegreenplace.net/2017/concurrent-servers-part-3-event-driven/

|

||

[10]:https://eli.thegreenplace.net/2017/concurrent-servers-part-1-introduction/#id4

|

||

[11]:https://github.com/eliben/code-for-blog/blob/master/2017/async-socket-server/sequential-server.c

|

||

[12]:https://eli.thegreenplace.net/2017/concurrent-servers-part-1-introduction/#id5

|

||

[13]:https://github.com/eliben/code-for-blog/tree/master/2017/async-socket-server

|

||

[14]:https://eli.thegreenplace.net/2017/concurrent-servers-part-1-introduction/#id6

|

||

[15]:http://eli.thegreenplace.net/2009/08/12/framing-in-serial-communications/

|

||

[16]:http://eli.thegreenplace.net/2009/08/29/co-routines-as-an-alternative-to-state-machines

|

||

[17]:http://beej.us/guide/bgnet/

|

||

[18]:https://eli.thegreenplace.net/2017/concurrent-servers-part-1-introduction/

|