mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-01-10 22:21:11 +08:00

177 lines

13 KiB

Markdown

177 lines

13 KiB

Markdown

translating by xiaow6

|

||

Your visual how-to guide for SELinux policy enforcement

|

||

============================================================

|

||

|

||

|

||

>Image by : opensource.com

|

||

|

||

We are celebrating the SELinux 10th year anversary this year. Hard to believe it. SELinux was first introduced in Fedora Core 3 and later in Red Hat Enterprise Linux 4. For those who have never used SELinux, or would like an explanation...

|

||

|

||

More Linux resources

|

||

|

||

* [What is Linux?][1]

|

||

* [What are Linux containers?][2]

|

||

* [Managing devices in Linux][3]

|

||

* [Download Now: Linux commands cheat sheet][4]

|

||

* [Our latest Linux articles][5]

|

||

|

||

SElinux is a labeling system. Every process has a label. Every file/directory object in the operating system has a label. Even network ports, devices, and potentially hostnames have labels assigned to them. We write rules to control the access of a process label to an a object label like a file. We call this _policy_ . The kernel enforces the rules. Sometimes this enforcement is called Mandatory Access Control (MAC).

|

||

|

||

The owner of an object does not have discretion over the security attributes of a object. Standard Linux access control, owner/group + permission flags like rwx, is often called Discretionary Access Control (DAC). SELinux has no concept of UID or ownership of files. Everything is controlled by the labels. Meaning an SELinux system can be setup without an all powerful root process.

|

||

|

||

**Note:** _SELinux does not let you side step DAC Controls. SELinux is a parallel enforcement model. An application has to be allowed by BOTH SELinux and DAC to do certain activities. This can lead to confusion for administrators because the process gets Permission Denied. Administrators see Permission Denied means something is wrong with DAC, not SELinux labels._

|

||

|

||

### Type enforcement

|

||

|

||

Lets look a little further into the labels. The SELinux primary model or enforcement is called _type enforcement_ . Basically this means we define the label on a process based on its type, and the label on a file system object based on its type.

|

||

|

||

_Analogy_

|

||

|

||

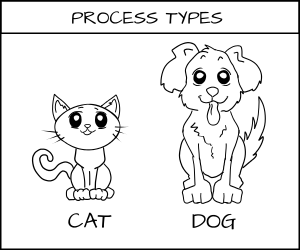

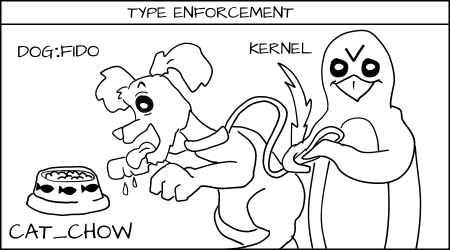

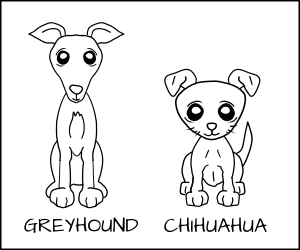

Imagine a system where we define types on objects like cats and dogs. A cat and dog are process types.

|

||

|

||

_*all cartoons by [Máirín Duffy][6]_

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

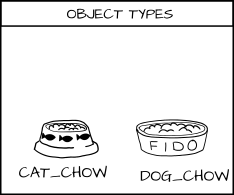

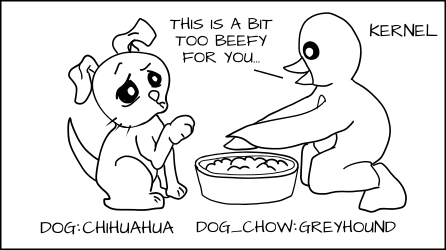

We have a class of objects that they want to interact with which we call food. And I want to add types to the food, _cat_food_ and _dog_food_ .

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

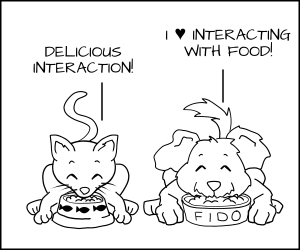

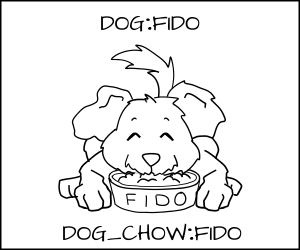

As a policy writer, I would say that a dog has permission to eat _dog_chow_ food and a cat has permission to eat _cat_chow_ food. In SELinux we would write this rule in policy.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

allow cat cat_chow:food eat;

|

||

|

||

allow dog dog_chow:food eat;

|

||

|

||

With these rules the kernel would allow the cat process to eat food labeled _cat_chow _ and the dog to eat food labeled _dog_chow_ .

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

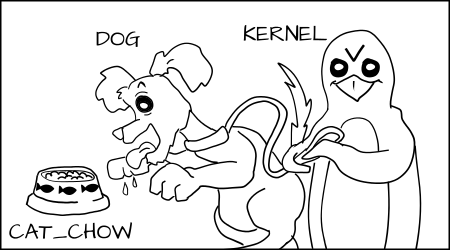

But in an SELinux system everything is denied by default. This means that if the dog process tried to eat the _cat_chow_ , the kernel would prevent it.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Likewise cats would not be allowed to touch dog food.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

_Real world_

|

||

|

||

We label Apache processes as _httpd_t_ and we label Apache content as _httpd_sys_content_t _ and _httpd_sys_content_rw_t_ . Imagine we have credit card data stored in a mySQL database which is labeled _msyqld_data_t_ . If an Apache process is hacked, the hacker could get control of the _httpd_t process_ and would be allowed to read _httpd_sys_content_t_ files and write to _httpd_sys_content_rw_t_ . But the hacker would not be allowed to read the credit card data ( _mysqld_data_t_ ) even if the process was running as root. In this case SELinux has mitigated the break in.

|

||

|

||

### MCS enforcement

|

||

|

||

_Analogy _

|

||

|

||

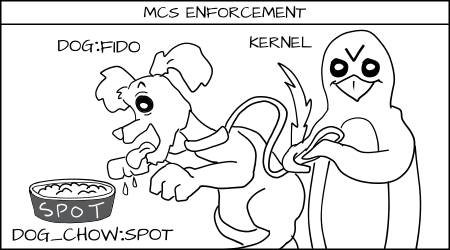

Above, we typed the dog process and cat process, but what happens if you have multiple dogs processes: Fido and Spot. You want to stop Fido from eating Spot's _dog_chow_ .

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

One solution would be to create lots of new types, like _Fido_dog_ and _Fido_dog_chow_ . But, this will quickly become unruly because all dogs have pretty much the same permissions.

|

||

|

||

To handle this we developed a new form of enforcement, which we call Multi Category Security (MCS). In MCS, we add another section of the label which we can apply to the dog process and to the dog_chow food. Now we label the dog process as _dog:random1 _ (Fido) and _dog:random2_ (Spot).

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

We label the dog chow as _dog_chow:random1 (Fido)_ and _dog_chow:random2_ (Spot).

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

MCS rules say that if the type enforcement rules are OK and the random MCS labels match exactly, then the access is allowed, if not it is denied.

|

||

|

||

Fido (dog:random1) trying to eat _cat_chow:food_ is denied by type enforcement.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Fido (dog:random1) is allowed to eat _dog_chow:random1._

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Fido (dog:random1) denied to eat spot's ( _dog_chow:random2_ ) food.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

_Real world_

|

||

|

||

In computer systems we often have lots of processes all with the same access, but we want them separated from each other. We sometimes call this a _multi-tenant environment_ . The best example of this is virtual machines. If I have a server running lots of virtual machines, and one of them gets hacked, I want to prevent it from attacking the other virtual machines and virtual machine images. But in a type enforcement system the KVM virtual machine is labeled _svirt_t_ and the image is labeled _svirt_image_t_ . We have rules that say _svirt_t_ can read/write/delete content labeled _svirt_image_t_ . With libvirt we implemented not only type enforcement separation, but also MCS separation. When libvirt is about to launch a virtual machine it picks out a random MCS label like _s0:c1,c2_ , it then assigns the _svirt_image_t:s0:c1,c2_ label to all of the content that the virtual machine is going to need to manage. Finally, it launches the virtual machine as _svirt_t:s0:c1,c2_ . Then, the SELinux kernel controls that _svirt_t:s0:c1,c2_ can not write to _svirt_image_t:s0:c3,c4_ , even if the virtual machine is controled by a hacker and takes it over. Even if it is running as root.

|

||

|

||

We use [similar separation][8] in OpenShift. Each gear (user/app process)runs with the same SELinux type (openshift_t). Policy defines the rules controlling the access of the gear type and a unique MCS label to make sure one gear can not interact with other gears.

|

||

|

||

Watch [this short video][9] on what would happen if an Openshift gear became root.

|

||

|

||

### MLS enforcement

|

||

|

||

Another form of SELinux enforcement, used much less frequently, is called Multi Level Security (MLS); it was developed back in the 60s and is used mainly in trusted operating systems like Trusted Solaris.

|

||

|

||

The main idea is to control processes based on the level of the data they will be using. A _secret _ process can not read _top secret_ data.

|

||

|

||

MLS is very similar to MCS, except it adds a concept of dominance to enforcement. Where MCS labels have to match exactly, one MLS label can dominate another MLS label and get access.

|

||

|

||

_Analogy_

|

||

|

||

Instead of talking about different dogs, we now look at different breeds. We might have a Greyhound and a Chihuahua.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

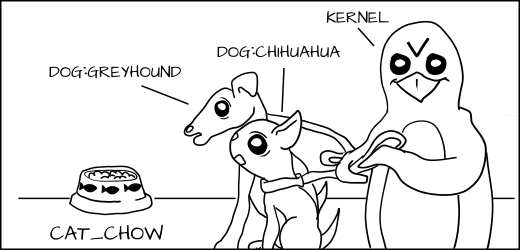

We might want to allow the Greyhound to eat any dog food, but a Chihuahua could choke if it tried to eat Greyhound dog food.

|

||

|

||

We want to label the Greyhound as _dog:Greyhound_ and his dog food as _dog_chow:Greyhound, _ and label the Chihuahua as _dog:Chihuahua_ and his food as _dog_chow:Chihuahua_ .

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

With the MLS policy, we would have the MLS Greyhound label dominate the Chihuahua label. This means _dog:Greyhound_ is allowed to eat _dog_chow:Greyhound _ and _dog_chow:Chihuahua_ .

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

But _dog:Chihuahua_ is not allowed to eat _dog_chow:Greyhound_ .

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Of course, _dog:Greyhound_ and _dog:Chihuahua_ are still prevented from eating _cat_chow:Siamese_ by type enforcement, even if the MLS type Greyhound dominates Siamese.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

_Real world_

|

||

|

||

I could have two Apache servers: one running as _httpd_t:TopSecret_ and another running as _httpd_t:Secret_ . If the Apache process _httpd_t:Secret_ were hacked, the hacker could read _httpd_sys_content_t:Secret_ but would be prevented from reading _httpd_sys_content_t:TopSecret_ .

|

||

|

||

However, if the Apache server running _httpd_t:TopSecret_ was hacked, it could read _httpd_sys_content_t:Secret data_ as well as _httpd_sys_content_t:TopSecret_ .

|

||

|

||

We use the MLS in military environments where a user might only be allowed to see _secret _ data, but another user on the same system could read _top secret_ data.

|

||

|

||

### Conclusion

|

||

|

||

SELinux is a powerful labeling system, controlling access granted to individual processes by the kernel. The primary feature of this is type enforcement where rules define the access allowed to a process is allowed based on the labeled type of the process and the labeled type of the object. Two additional controls have been added to separate processes with the same type from each other called MCS, total separtion from each other, and MLS, allowing for process domination.

|

||

|

||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||

|

||

作者简介:

|

||

|

||

Daniel J Walsh - Daniel Walsh has worked in the computer security field for almost 30 years. Dan joined Red Hat in August 2001.

|

||

|

||

-------------------------

|

||

|

||

via: https://opensource.com/business/13/11/selinux-policy-guide

|

||

|

||

作者:[Daniel J Walsh ][a]

|

||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||

|

||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||

|

||

[a]:https://opensource.com/users/rhatdan

|

||

[1]:https://opensource.com/resources/what-is-linux?src=linux_resource_menu

|

||

[2]:https://opensource.com/resources/what-are-linux-containers?src=linux_resource_menu

|

||

[3]:https://opensource.com/article/16/11/managing-devices-linux?src=linux_resource_menu

|

||

[4]:https://developers.redhat.com/promotions/linux-cheatsheet/?intcmp=7016000000127cYAAQ

|

||

[5]:https://opensource.com/tags/linux?src=linux_resource_menu

|

||

[6]:https://opensource.com/users/mairin

|

||

[7]:https://opensource.com/business/13/11/selinux-policy-guide?rate=XNCbBUJpG2rjpCoRumnDzQw-VsLWBEh-9G2hdHyB31I

|

||

[8]:http://people.fedoraproject.org/~dwalsh/SELinux/Presentations/openshift_selinux.ogv

|

||

[9]:http://people.fedoraproject.org/~dwalsh/SELinux/Presentations/openshift_selinux.ogv

|

||

[10]:https://opensource.com/user/16673/feed

|

||

[11]:https://opensource.com/business/13/11/selinux-policy-guide#comments

|

||

[12]:https://opensource.com/users/rhatdan

|