17 KiB

alim0x translating

Android 6.0 Marshmallow

In October 2015, Google brought Android 6.0 Marshmallow into the world. For the OS's launch, Google commissioned two new Nexus devices: the Huawei Nexus 6P and LG Nexus 5X. Rather than just the usual speed increase, the new phones also included a key piece of hardware: a fingerprint reader for Marshmallow's new fingerprint API. Marshmallow was also packing a crazy new search feature called "Google Now on Tap," user controlled app permissions, a new data backup system, and plenty of other refinements.

The new Google App

Marshmallow was the first version of Android after Google's big logo redesign. The OS was updated accordingly, mainly with a new Google app that added a colorful logo to the search widget, search page, and the app icon.

Google reverted the app drawer from a paginated horizontal layout back to the single, vertically scrolling sheet. The earliest versions of Android all had vertically scrolling sheets until Google changed to a horizontal page system in Honeycomb. The scrolling single sheet made finding things in a large selection of apps much faster. A "quick scroll" feature, which let you drag on the scroll bar to bring up letter indexing, helped too. This new app drawer layout also carried over to the widget drawer. Given that the old system could easily grow to 15+ pages, this was a big improvement.

The "suggested apps" bar at the top of Marshmallow's app drawer made finding apps faster, too. This bar changed from time to time and tried to surface the apps you needed when you needed them. It used an algorithm that took into account app usage, apps that are normally launched together, and time of day.

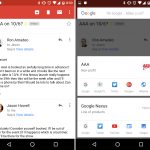

Google Now on Tap—a feature that didn't quite work out

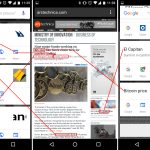

One of Marshmallow's headline features was "Google Now on Tap." With Now on Tap, you could hold down the home button on any screen and Android would send the entire screen to Google for processing. Google would then try to figure out what the screen was about, and a special list of search results would pop up from the bottom of the screen.

Results yielded by Now on Tap weren't the usual 10 blue links—though there was always a link to a Google Search. Now on Tap could also deep link into other apps using Google's App Indexing feature. The idea was you could call up Now on Tap for a YouTube music video and get a link to the Google Play or Amazon "buy" page. Now on Tapping (am I allowed to verb that?) a news article about an actor could link to his page inside the IMDb app.

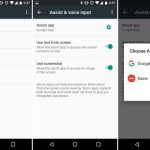

Rather than make this a proprietary feature, Google built a whole new "Assistant API" into Android. The user could pick an "Assist App" which would be granted scads of information upon long-pressing the home button. The Assist app would get all the text that was currently loaded by the app—not just what was immediately on screen—along with all the images and any special metadata the developer wanted to include. This API powered Google Now on Tap, and it also allowed third parties to make Now on Tap rivals if they wished.

Google hyped Now on Tap during Marshmallow's initial presentation, but in practice, the feature wasn't very useful. Google Search is worthwhile because you're asking it an exact question—you type in whatever you want, and it scours the entire Internet looking for the answer or web page. Now on Tap made things infinitely harder because it didn't even know what question you were asking. You opened Now on Tap with a very specific intent, but you sent Google the very unspecific query of "everything on your screen." Google had to guess what your query was and then tried to deliver useful search results or actions based on that.

Behind the scenes, Google was probably processing like crazy to brute-force out the result you wanted from an entire page of text and images. But more often than not, Now on Tap yielded what felt like a list of search results for every proper noun on the page. Sifting through the list of results for multiple queries was like being trapped in one of those Bing "Search Overload" commercials. The lack of any kind of query targeting made Now on Tap feel like you were asking Google to read your mind, and it never could. Google eventually patched in an "Assist" button to the text selection menu, giving Now on Tap some of the query targeting that it desperately needed.

Calling Now on Tap anything other than a failure is hard. The shortcut to access Now on Tap—long pressing on the home button—basically made it a hidden, hard-to-discover feature that was easy to forget about. We speculate the feature had extremely low usage numbers. Even when users did discover Now on Tap, it failed to read your mind so often that, after a few attempts, most users probably gave up on it.

With the launch of the Google Pixels in 2016, the company seemingly admitted defeat. It renamed Now on Tap "Screen Search" and demoted it in favor of the Google Assistant. The Assistant—Google's new voice command system—took over On Tap's home button gesture and related it to a second gesture once the voice system was activated. Google also seems to have learned from Now on Tap's poor discoverability. With the Assistant, Google added a set of animated colored dots to the home button that helped users discover and be reminded about the feature.

Permissions

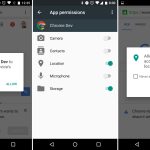

Android 6.0 finally introduced an app permissions system that gave users granular control over what data apps had access to.

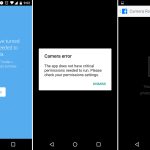

Apps no longer gave you a huge list of permissions at install. With Marshmallow, apps installed without asking for any permissions at all. When apps needed a permission—like access to your location, camera, microphone, or contact list—they asked at the exact time they needed it. During your usage of an app, an "Allow or Deny" dialog popped up anytime the app wanted a new permission. Some app setup flow tackled this by asking for a few key permissions at startup, and everything else popped up as the app needed it. This better communicated to the user what the permissions are for—this app needs camera access because you just tapped on the camera button.

Besides the in-the-moment "Allow or Deny" dialogs, Marshmallow also added a permissions setting screen. This big list of checkboxes allowed data-conscious users to browse which apps have access to what permissions. They can browse not only by app, but also by permission. For instance, you could see every app that has access to the microphone.

Google had been experimenting with app permissions for some time, and these screens were basically the rebirth of the hidden "App Ops" system that was accidentally introduced in Android 4.3 and quickly removed.

While Google experimented in previous versions, the big difference with Marshmallow's permissions system was that it represented an orderly transition to a permission OS. Android 4.3's App Ops was never meant to be exposed to users, so developers didn't know about it. The result of denying an app a permission in 4.3 was often a weird error message or an outright crash. Marshmallow's system was opt-in for developers—the new permission system only applied to apps that were targeting the Marshmallow SDK, which Google used as a signal that the developer was ready for permission handling. The system also allowed for communication to users when a feature didn't work because of a denied permission. Apps were told when they were denied a permission, and they could instruct the user to turn the permission back on if you wanted to use a feature.

The Fingerprint API

Before Marshmallow, few OEMs had come up with their own fingerprint solution in response to Apple's Touch ID. But with Marshmallow, Google finally came up with an ecosystem-wide API for fingerprint recognition. The new system included UI for registering fingerprints, a fingerprint-guarded lock screen, and APIs that allowed apps to protect content behind a fingerprint scan or lock-screen challenge.

The Play Store was one of the first apps to support the API. Instead of having to enter your password to purchase an app, you could just use your fingerprint. The Nexus 5X and 6P were the first phones to support the fingerprint API with an actual hardware fingerprint reader on the back.

Later the fingerprint API became one of the rare examples of the Android ecosystem actually cooperating and working together. Every phone with a fingerprint reader uses Google's API, and most banking and purchasing apps are pretty good about supporting it.

作者简介:

Ron is the Reviews Editor at Ars Technica, where he specializes in Android OS and Google products. He is always on the hunt for a new gadget and loves to rip things apart to see how they work.

作者:RON AMADEO 译者:译者ID 校对:校对者ID