mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-01-10 22:21:11 +08:00

309 lines

13 KiB

Markdown

309 lines

13 KiB

Markdown

translating by Flowsnow

|

||

What is behavior-driven Python?

|

||

======

|

||

|

||

Have you heard about [behavior-driven development][1] (BDD) and wondered what all the buzz is about? Maybe you've caught team members talking in "gherkin" and felt left out of the conversation. Or perhaps you're a Pythonista looking for a better way to test your code. Whatever the circumstance, learning about BDD can help you and your team achieve better collaboration and test automation, and Python's `behave` framework is a great place to start.

|

||

|

||

### What is BDD?

|

||

|

||

* Submitting forms on a website

|

||

* Searching for desired results

|

||

* Saving a document

|

||

* Making REST API calls

|

||

* Running command-line interface commands

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

In software, a behavior is how a feature operates within a well-defined scenario of inputs, actions, and outcomes. Products can exhibit countless behaviors, such as:

|

||

|

||

Defining a product's features based on its behaviors makes it easier to describe them, develop them, and test them. This is the heart of BDD: making behaviors the focal point of software development. Behaviors are defined early in development using a [specification by example][2] language. One of the most common behavior spec languages is [Gherkin][3], the Given-When-Then scenario format from the [Cucumber][4] project. Behavior specs are basically plain-language descriptions of how a behavior works, with a little bit of formal structure for consistency and focus. Test frameworks can easily automate these behavior specs by "gluing" step texts to code implementations.

|

||

|

||

Below is an example of a behavior spec written in Gherkin:

|

||

```

|

||

Scenario: Basic DuckDuckGo Search

|

||

|

||

Given the DuckDuckGo home page is displayed

|

||

|

||

When the user searches for "panda"

|

||

|

||

Then results are shown for "panda"

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

At a quick glance, the behavior is intuitive to understand. Except for a few keywords, the language is freeform. The scenario is concise yet meaningful. A real-world example illustrates the behavior. Steps declaratively indicate what should happen—without getting bogged down in the details of how.

|

||

|

||

The [main benefits of BDD][5] are good collaboration and automation. Everyone can contribute to behavior development, not just programmers. Expected behaviors are defined and understood from the beginning of the process. Tests can be automated together with the features they cover. Each test covers a singular, unique behavior in order to avoid duplication. And, finally, existing steps can be reused by new behavior specs, creating a snowball effect.

|

||

|

||

### Python's behave framework

|

||

|

||

`behave` is one of the most popular BDD frameworks in Python. It is very similar to other Gherkin-based Cucumber frameworks despite not holding the official Cucumber designation. `behave` has two primary layers:

|

||

|

||

1. Behavior specs written in Gherkin `.feature` files

|

||

2. Step definitions and hooks written in Python modules that implement Gherkin steps

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

As shown in the example above, Gherkin scenarios use a three-part format:

|

||

|

||

1. Given some initial state

|

||

2. When an action is taken

|

||

3. Then verify the outcome

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Each step is "glued" by decorator to a Python function when `behave` runs tests.

|

||

|

||

### Installation

|

||

|

||

As a prerequisite, make sure you have Python and `pip` installed on your machine. I strongly recommend using Python 3. (I also recommend using [`pipenv`][6], but the following example commands use the more basic `pip`.)

|

||

|

||

Only one package is required for `behave`:

|

||

```

|

||

pip install behave

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Other packages may also be useful, such as:

|

||

```

|

||

pip install requests # for REST API calls

|

||

|

||

pip install selenium # for Web browser interactions

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

The [behavior-driven-Python][7] project on GitHub contains the examples used in this article.

|

||

|

||

### Gherkin features

|

||

|

||

The Gherkin syntax that `behave` uses is practically compliant with the official Cucumber Gherkin standard. A `.feature` file has Feature sections, which in turn have Scenario sections with Given-When-Then steps. Below is an example:

|

||

```

|

||

Feature: Cucumber Basket

|

||

|

||

As a gardener,

|

||

|

||

I want to carry many cucumbers in a basket,

|

||

|

||

So that I don’t drop them all.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

@cucumber-basket

|

||

|

||

Scenario: Add and remove cucumbers

|

||

|

||

Given the basket is empty

|

||

|

||

When "4" cucumbers are added to the basket

|

||

|

||

And "6" more cucumbers are added to the basket

|

||

|

||

But "3" cucumbers are removed from the basket

|

||

|

||

Then the basket contains "7" cucumbers

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

There are a few important things to note here:

|

||

|

||

* Both the Feature and Scenario sections have [short, descriptive titles][8].

|

||

* The lines immediately following the Feature title are comments ignored by `behave`. It is a good practice to put the user story there.

|

||

* Scenarios and Features can have tags (notice the `@cucumber-basket` mark) for hooks and filtering (explained below).

|

||

* Steps follow a [strict Given-When-Then order][9].

|

||

* Additional steps can be added for any type using `And` and `But`.

|

||

* Steps can be parametrized with inputs—notice the values in double quotes.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Scenarios can also be written as templates with multiple input combinations by using a Scenario Outline:

|

||

```

|

||

Feature: Cucumber Basket

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

@cucumber-basket

|

||

|

||

Scenario Outline: Add cucumbers

|

||

|

||

Given the basket has “<initial>” cucumbers

|

||

|

||

When "<more>" cucumbers are added to the basket

|

||

|

||

Then the basket contains "<total>" cucumbers

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Examples: Cucumber Counts

|

||

|

||

| initial | more | total |

|

||

|

||

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

|

||

|

||

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

|

||

|

||

| 5 | 4 | 9 |

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Scenario Outlines always have an Examples table, in which the first row gives column titles and each subsequent row gives an input combo. The row values are substituted wherever a column title appears in a step surrounded by angle brackets. In the example above, the scenario will be run three times because there are three rows of input combos. Scenario Outlines are a great way to avoid duplicate scenarios.

|

||

|

||

There are other elements of the Gherkin language, but these are the main mechanics. To learn more, read the Automation Panda articles [Gherkin by Example][10] and [Writing Good Gherkin][11].

|

||

|

||

### Python mechanics

|

||

|

||

Every Gherkin step must be "glued" to a step definition, a Python function that provides the implementation. Each function has a step type decorator with the matching string. It also receives a shared context and any step parameters. Feature files must be placed in a directory named `features/`, while step definition modules must be placed in a directory named `features/steps/`. Any feature file can use step definitions from any module—they do not need to have the same names. Below is an example Python module with step definitions for the cucumber basket features.

|

||

```

|

||

from behave import *

|

||

|

||

from cucumbers.basket import CucumberBasket

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

@given('the basket has "{initial:d}" cucumbers')

|

||

|

||

def step_impl(context, initial):

|

||

|

||

context.basket = CucumberBasket(initial_count=initial)

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

@when('"{some:d}" cucumbers are added to the basket')

|

||

|

||

def step_impl(context, some):

|

||

|

||

context.basket.add(some)

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

@then('the basket contains "{total:d}" cucumbers')

|

||

|

||

def step_impl(context, total):

|

||

|

||

assert context.basket.count == total

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Three [step matchers][12] are available: `parse`, `cfparse`, and `re`. The default and simplest marcher is `parse`, which is shown in the example above. Notice how parametrized values are parsed and passed into the functions as input arguments. A common best practice is to put double quotes around parameters in steps.

|

||

|

||

Each step definition function also receives a [context][13] variable that holds data specific to the current scenario being run, such as `feature`, `scenario`, and `tags` fields. Custom fields may be added, too, to share data between steps. Always use context to share data—never use global variables!

|

||

|

||

`behave` also supports [hooks][14] to handle automation concerns outside of Gherkin steps. A hook is a function that will be run before or after a step, scenario, feature, or whole test suite. Hooks are reminiscent of [aspect-oriented programming][15]. They should be placed in a special `environment.py` file under the `features/` directory. Hook functions can check the current scenario's tags, as well, so logic can be selectively applied. The example below shows how to use hooks to set up and tear down a Selenium WebDriver instance for any scenario tagged as `@web`.

|

||

```

|

||

from selenium import webdriver

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

def before_scenario(context, scenario):

|

||

|

||

if 'web' in context.tags:

|

||

|

||

context.browser = webdriver.Firefox()

|

||

|

||

context.browser.implicitly_wait(10)

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

def after_scenario(context, scenario):

|

||

|

||

if 'web' in context.tags:

|

||

|

||

context.browser.quit()

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

Note: Setup and cleanup can also be done with [fixtures][16] in `behave`.

|

||

|

||

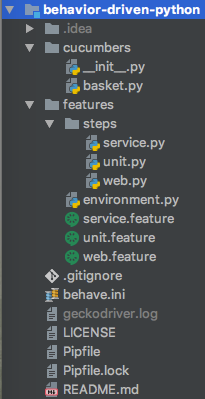

To offer an idea of what a `behave` project should look like, here's the example project's directory structure:

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Any Python packages and custom modules can be used with `behave`. Use good design patterns to build a scalable test automation solution. Step definition code should be concise.

|

||

|

||

### Running tests

|

||

|

||

To run tests from the command line, change to the project's root directory and run the `behave` command. Use the `–help` option to see all available options.

|

||

|

||

Below are a few common use cases:

|

||

```

|

||

# run all tests

|

||

|

||

behave

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

# run the scenarios in a feature file

|

||

|

||

behave features/web.feature

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

# run all tests that have the @duckduckgo tag

|

||

|

||

behave --tags @duckduckgo

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

# run all tests that do not have the @unit tag

|

||

|

||

behave --tags ~@unit

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

# run all tests that have @basket and either @add or @remove

|

||

|

||

behave --tags @basket --tags @add,@remove

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

For convenience, options may be saved in [config][17] files.

|

||

|

||

### Other options

|

||

|

||

`behave` is not the only BDD test framework in Python. Other good frameworks include:

|

||

|

||

* `pytest-bdd` , a plugin for `pytest``behave`, it uses Gherkin feature files and step definition modules, but it also leverages all the features and plugins of `pytest`. For example, it can run Gherkin scenarios in parallel using `pytest-xdist`. BDD and non-BDD tests can also be executed together with the same filters. `pytest-bdd` also offers a more flexible directory layout.

|

||

|

||

* `radish` is a "Gherkin-plus" framework—it adds Scenario Loops and Preconditions to the standard Gherkin language, which makes it more friendly to programmers. It also offers rich command line options like `behave`.

|

||

|

||

* `lettuce` is an older BDD framework very similar to `behave`, with minor differences in framework mechanics. However, GitHub shows little recent activity in the project (as of May 2018).

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Any of these frameworks would be good choices.

|

||

|

||

Also, remember that Python test frameworks can be used for any black box testing, even for non-Python products! BDD frameworks are great for web and service testing because their tests are declarative, and Python is a [great language for test automation][18].

|

||

|

||

This article is based on the author's [PyCon Cleveland 2018][19] talk, [Behavior-Driven Python][20].

|

||

|

||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||

|

||

via: https://opensource.com/article/18/5/behavior-driven-python

|

||

|

||

作者:[Andrew Knight][a]

|

||

选题:[lujun9972](https://github.com/lujun9972)

|

||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||

|

||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||

|

||

[a]:https://opensource.com/users/andylpk247

|

||

[1]:https://automationpanda.com/bdd/

|

||

[2]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Specification_by_example

|

||

[3]:https://automationpanda.com/2017/01/26/bdd-101-the-gherkin-language/

|

||

[4]:https://cucumber.io/

|

||

[5]:https://automationpanda.com/2017/02/13/12-awesome-benefits-of-bdd/

|

||

[6]:https://docs.pipenv.org/

|

||

[7]:https://github.com/AndyLPK247/behavior-driven-python

|

||

[8]:https://automationpanda.com/2018/01/31/good-gherkin-scenario-titles/

|

||

[9]:https://automationpanda.com/2018/02/03/are-gherkin-scenarios-with-multiple-when-then-pairs-okay/

|

||

[10]:https://automationpanda.com/2017/01/27/bdd-101-gherkin-by-example/

|

||

[11]:https://automationpanda.com/2017/01/30/bdd-101-writing-good-gherkin/

|

||

[12]:http://behave.readthedocs.io/en/latest/api.html#step-parameters

|

||

[13]:http://behave.readthedocs.io/en/latest/api.html#detecting-that-user-code-overwrites-behave-context-attributes

|

||

[14]:http://behave.readthedocs.io/en/latest/api.html#environment-file-functions

|

||

[15]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aspect-oriented_programming

|

||

[16]:http://behave.readthedocs.io/en/latest/api.html#fixtures

|

||

[17]:http://behave.readthedocs.io/en/latest/behave.html#configuration-files

|

||

[18]:https://automationpanda.com/2017/01/21/the-best-programming-language-for-test-automation/

|

||

[19]:https://us.pycon.org/2018/

|

||

[20]:https://us.pycon.org/2018/schedule/presentation/87/

|