9.3 KiB

3 reasons to say 'no' in DevOps

DevOps, it has often been pointed out, is a culture that emphasizes mutual respect, cooperation, continual improvement, and aligning responsibility with authority.

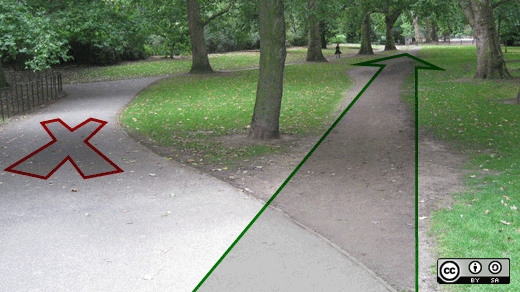

Instead of saying no, it may be helpful to take a hint from improv comedy and say, "Yes, and..." or "Yes, but...". This opens the request from the binary nature of "yes" and "no" toward having a nuanced discussion around priority, capacity, and responsibility.

However, sometimes you have no choice but to give a hard "no." These should be rare and exceptional, but they will occur.

Protecting yourself

Both Agile and DevOps have been touted as ways to improve value to the customer and business, ultimately leading to greater productivity. While reasonable people can understand that the improvements will take time to yield, and the improvements will result in higher quality of work being done, and a better quality of life for those performing it, I think we can all agree that not everyone is reasonable. The less understanding that a person has of the particulars of a given task, the more likely they are to expect that it is a combination of "simple" and "easy."

"You told me that [Agile/DevOps] is supposed to be all about us getting more productivity. Since we're doing [Agile/DevOps] now, you can take care of my need, right?"

Like "Agile," some people have tried to use "DevOps" as a stick to coerce people to do more work than they can handle. Whether the person confronting you with this question is asking in earnest or is being manipulative doesn't really matter.

The biggest areas of concern for me have been capacity , firefighting/maintenance , level of quality , and " future me." Many of these ultimately tie back to capacity, but they relate to a long-term effort in different respects.

Capacity

Capacity is simple: You know what your workload is, and how much flex occurs due to the unexpected. Exceeding your capacity will not only cause undue stress, but it could decrease the quality of your work and can injure your reputation with regards to making commitments.

There are several avenues of discussion that can happen from here. The simplest is "Your request is reasonable, but I don't have the capacity to work on it." This seldom ends the conversation, and a discussion will often run up the flagpole to clarify priorities or reassign work.

Firefighting/maintenance

It's possible that the thing that you're being asked for won't take long to do, but it will require maintenance that you'll be expected to perform, including keeping it alive and fulfilling requests for it on behalf of others.

An example in my mind is the Jenkins server that you're asked to stand up for someone else, but somehow end up being the sole owner and caretaker of. Even if you're careful to scope your level of involvement early on, you might be saddled with responsibility that you did not agree to. Should the service become unavailable, for example, you might be the one who is called. You might be called on to help triage a build that is failing. This is additional firefighting and maintenance work that you did not sign up for and now must fend off.

This needs to be addressed as soon and publicly as possible. I'm not saying that (again, for example) standing up a Jenkins instance is a "no," but rather a "Yes, but"—where all parties understand that they take on the long-term care, feeding, and use of the product. Make sure to include all your bosses in this conversation so they can have your back.

Level of quality

There may be times when you are presented with requirements that include a timeframe that is...problematic. Perhaps you could get a "minimum (cough) viable (cough) product" out in that time. But it wouldn't be resilient or in any way ready for production. It might impact your time and productivity. It could end up hurting your reputation.

The resulting conversation can get into the weeds, with lots of horse-trading about time and features. Another approach is to ask "What is driving this deadline? Where did that timeframe come from?" Discussing the bigger picture might lead to a better option, or that the timeline doesn't depend on the original date.

Future me

Ultimately, we are trying to protect "future you." These are lessons learned from the many times that "past me" has knowingly left "current me" to clean up. Sometimes we joke that "that's a problem for 'future me,'" but don't forget that 'future you' will just be 'you' eventually. I've cursed "past me" as a jerk many times. Do your best to keep other people from making "past you" be a jerk to "future you."

I recognize that I have a significant amount of privilege in this area, but if you are told that you cannot say "no" on behalf of your own welfare, you should consider whether you are respected enough to maintain your autonomy.

Protecting the user experience

Everyone should be an advocate for the user. Regardless of whether that user is right next to you, someone down the hall, or someone you have never met and likely never will, you must care for the customer.

Behavior that is actively hostile to the user—whether it's a poor user experience or something more insidious like quietly violating reasonable expectations of privacy—deserves a "no." A common example of this would be automatically including people into a service or feature, forcing them to explicitly opt-out.

If a "no" is not welcome, it bears considering, or explicitly asking, what the company's relationship with its customers is, who the company thinks of as it's customers, and what it thinks of them.

When bringing up your objections, be clear about what they are. Additionally, remember that your coworkers are people too, and make it clear that you are not attacking their character; you simply find the idea disagreeable.

Legal, ethical, and moral grounds

There might be situations that don't feel right. A simple test is to ask: "If this were to become public, or come up in a lawsuit deposition, would it be a scandal?"

Ethics and morals

If you are asked to lie, that should be a hard no.

Remember if you will the Volkswagen Emissions Scandal of 2017? The emissions systems software was written such that it recognized that the vehicle was operated in a manner consistent with an emissions test, and would run more efficiently than under normal driving conditions.

I don't know what you do in your job, or what your office is like, but I have a hard time imagining the Individual Contributor software engineer coming up with that as a solution on their own. In fact, I imagine a comment along the lines of "the engine engineers can't make their product pass the tests, so I need to hack the performance so that it will!"

When the Volkswagen scandal came public, Volkswagen officials blamed the engineers. I find it unlikely that it came from the mind and IDE of an individual software engineer. Rather, it's more likely indicates significant systemic problems within the company culture.

If you are asked to lie, get the request in writing, citing that the circumstances are suspect. If you are so privileged, decide whether you may decline the request on the basis that it is fundamentally dishonest and hostile to the customer, and would break the public's trust.

Legal

I am not a lawyer. If your work should involve legal matters, including requests from law enforcement, involve your company's legal counsel or speak with a private lawyer.

With that said, if you are asked to provide information for law enforcement, I believe that you are within your rights to see the documentation that justifies the request. There should be a signed warrant. You should be provided with a copy of it, or make a copy of it yourself.

When in doubt, begin recording and request legal counsel.

It has been well documented that especially in the early years of the U.S. Patriot Act, law enforcement placed so many requests of telecoms that they became standard work, and the paperwork started slipping. While tedious and potentially stressful, make sure that the legal requirements for disclosure are met.

If for no other reason, we would not want the good work of law enforcement to be put at risk because key evidence was improperly acquired, making it inadmissible.

Wrapping up

You are going to be your single biggest advocate. There may be times when you are asked to compromise for the greater good. However, you should feel that your dignity is preserved, your autonomy is respected, and that your morals remain intact.

If you don't feel that this is the case, get it on record, doing your best to communicate it calmly and clearly.

Nobody likes being declined, but if you don't have the ability to say no, there may be a bigger problem than your environment not being DevOps.

via: https://opensource.com/article/18/2/3-reasons-say-no-devops

作者:H. "Waldo" Grunenwal 译者:译者ID 校对:校对者ID