21 KiB

Part 3 - LFCS: How to Archive/Compress Files & Directories, Setting File Attributes and Finding Files in Linux

Recently, the Linux Foundation started the LFCS (Linux Foundation Certified Sysadmin) certification, a brand new program whose purpose is allowing individuals from all corners of the globe to have access to an exam, which if approved, certifies that the person is knowledgeable in performing basic to intermediate system administration tasks on Linux systems. This includes supporting already running systems and services, along with first-level troubleshooting and analysis, plus the ability to decide when to escalate issues to engineering teams.

Linux Foundation Certified Sysadmin – Part 3

Please watch the below video that gives the idea about The Linux Foundation Certification Program.

注:youtube 视频

This post is Part 3 of a 10-tutorial series, here in this part, we will cover how to archive/compress files and directories, set file attributes, and find files on the filesystem, that are required for the LFCS certification exam.

Archiving and Compression Tools

A file archiving tool groups a set of files into a single standalone file that we can backup to several types of media, transfer across a network, or send via email. The most frequently used archiving utility in Linux is tar. When an archiving utility is used along with a compression tool, it allows to reduce the disk size that is needed to store the same files and information.

The tar utility

tar bundles a group of files together into a single archive (commonly called a tar file or tarball). The name originally stood for tape archiver, but we must note that we can use this tool to archive data to any kind of writeable media (not only to tapes). Tar is normally used with a compression tool such as gzip, bzip2, or xz to produce a compressed tarball.

Basic syntax:

# tar [options] [pathname ...]

Where … represents the expression used to specify which files should be acted upon.

Most commonly used tar commands

注:表格

| Long option | Abbreviation | Description |

| –create | c | Creates a tar archive |

| –concatenate | A | Appends tar files to an archive |

| –append | r | Appends files to the end of an archive |

| –update | u | Appends files newer than copy in archive |

| –diff or –compare | d | Find differences between archive and file system |

| –file archive | f | Use archive file or device ARCHIVE |

| –list | t | Lists the contents of a tarball |

| –extract or –get | x | Extracts files from an archive |

Normally used operation modifiers

注:表格

| Long option | Abbreviation | Description |

| –directory dir | C | Changes to directory dir before performing operations |

| –same-permissions | p | Preserves original permissions |

| –verbose | v | Lists all files read or extracted. When this flag is used along with –list, the file sizes, ownership, and time stamps are displayed. |

| –verify | W | Verifies the archive after writing it |

| –exclude file | — | Excludes file from the archive |

| –exclude=pattern | X | Exclude files, given as a PATTERN |

| –gzip or –gunzip | z | Processes an archive through gzip |

| –bzip2 | j | Processes an archive through bzip2 |

| –xz | J | Processes an archive through xz |

Gzip is the oldest compression tool and provides the least compression, while bzip2 provides improved compression. In addition, xz is the newest but (usually) provides the best compression. This advantages of best compression come at a price: the time it takes to complete the operation, and system resources used during the process.

Normally, tar files compressed with these utilities have .gz, .bz2, or .xz extensions, respectively. In the following examples we will be using these files: file1, file2, file3, file4, and file5.

Grouping and compressing with gzip, bzip2 and xz

Group all the files in the current working directory and compress the resulting bundle with gzip, bzip2, and xz (please note the use of a regular expression to specify which files should be included in the bundle – this is to prevent the archiving tool to group the tarballs created in previous steps).

# tar czf myfiles.tar.gz file[0-9]

# tar cjf myfiles.tar.bz2 file[0-9]

# tar cJf myfile.tar.xz file[0-9]

Compress Multiple Files

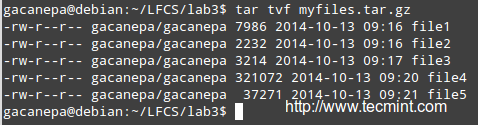

Listing the contents of a tarball and updating / appending files to the bundle

List the contents of a tarball and display the same information as a long directory listing. Note that update or append operations cannot be applied to compressed files directly (if you need to update or append a file to a compressed tarball, you need to uncompress the tar file and update / append to it, then compress again).

# tar tvf [tarball]

List Archive Content

Run any of the following commands:

# gzip -d myfiles.tar.gz [#1]

# bzip2 -d myfiles.tar.bz2 [#2]

# xz -d myfiles.tar.xz [#3]

Then

# tar --delete --file myfiles.tar file4 (deletes the file inside the tarball)

# tar --update --file myfiles.tar file4 (adds the updated file)

and

# gzip myfiles.tar [ if you choose #1 above ]

# bzip2 myfiles.tar [ if you choose #2 above ]

# xz myfiles.tar [ if you choose #3 above ]

Finally,

# tar tvf [tarball] #again

and compare the modification date and time of file4 with the same information as shown earlier.

Excluding file types

Suppose you want to perform a backup of user’s home directories. A good sysadmin practice would be (may also be specified by company policies) to exclude all video and audio files from backups.

Maybe your first approach would be to exclude from the backup all files with an .mp3 or .mp4 extension (or other extensions). What if you have a clever user who can change the extension to .txt or .bkp, your approach won’t do you much good. In order to detect an audio or video file, you need to check its file type with file. The following shell script will do the job.

#!/bin/bash

# Pass the directory to backup as first argument.

DIR=$1

# Create the tarball and compress it. Exclude files with the MPEG string in its file type.

# -If the file type contains the string mpeg, $? (the exit status of the most recently executed command) expands to 0, and the filename is redirected to the exclude option. Otherwise, it expands to 1.

# -If $? equals 0, add the file to the list of files to be backed up.

tar X <(for i in $DIR/*; do file $i | grep -i mpeg; if [ $? -eq 0 ]; then echo $i; fi;done) -cjf backupfile.tar.bz2 $DIR/*

Exclude Files in tar

Restoring backups with tar preserving permissions

You can then restore the backup to the original user’s home directory (user_restore in this example), preserving permissions, with the following command.

# tar xjf backupfile.tar.bz2 --directory user_restore --same-permissions

Restore Files from Archive

Read Also:

Using find Command to Search for Files

The find command is used to search recursively through directory trees for files or directories that match certain characteristics, and can then either print the matching files or directories or perform other operations on the matches.

Normally, we will search by name, owner, group, type, permissions, date, and size.

Basic syntax:

find [directory_to_search] [expression]

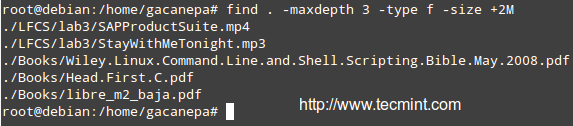

Finding files recursively according to Size

Find all files (-f) in the current directory (.) and 2 subdirectories below (-maxdepth 3 includes the current working directory and 2 levels down) whose size (-size) is greater than 2 MB.

# find . -maxdepth 3 -type f -size +2M

Find Files Based on Size

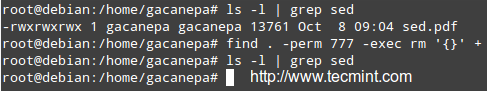

Finding and deleting files that match a certain criteria

Files with 777 permissions are sometimes considered an open door to external attackers. Either way, it is not safe to let anyone do anything with files. We will take a rather aggressive approach and delete them! (‘{}‘ + is used to “collect” the results of the search).

# find /home/user -perm 777 -exec rm '{}' +

Find Files with 777Permission

Finding files per atime or mtime

Search for configuration files in /etc that have been accessed (-atime) or modified (-mtime) more (+180) or less (-180) than 6 months ago or exactly 6 months ago (180).

Modify the following command as per the example below:

# find /etc -iname "*.conf" -mtime -180 -print

Find Modified Files

File Permissions and Basic Attributes

The first 10 characters in the output of ls -l are the file attributes. The first of these characters is used to indicate the file type:

- – : a regular file

- -d : a directory

- -l : a symbolic link

- -c : a character device (which treats data as a stream of bytes, i.e. a terminal)

- -b : a block device (which handles data in blocks, i.e. storage devices)

The next nine characters of the file attributes are called the file mode and represent the read (r), write (w), and execute (x) permissions of the file’s owner, the file’s group owner, and the rest of the users (commonly referred to as “the world”).

Whereas the read permission on a file allows the same to be opened and read, the same permission on a directory allows its contents to be listed if the execute permission is also set. In addition, the execute permission in a file allows it to be handled as a program and run, while in a directory it allows the same to be cd’ed into it.

File permissions are changed with the chmod command, whose basic syntax is as follows:

# chmod [new_mode] file

Where new_mode is either an octal number or an expression that specifies the new permissions.

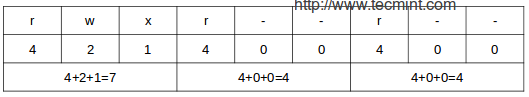

The octal number can be converted from its binary equivalent, which is calculated from the desired file permissions for the owner, the group, and the world, as follows:

The presence of a certain permission equals a power of 2 (r=22, w=21, x=20), while its absence equates to 0. For example:

File Permissions

To set the file’s permissions as above in octal form, type:

# chmod 744 myfile

You can also set a file’s mode using an expression that indicates the owner’s rights with the letter u, the group owner’s rights with the letter g, and the rest with o. All of these “individuals” can be represented at the same time with the letter a. Permissions are granted (or revoked) with the + or – signs, respectively.

Revoking execute permission for a shell script to all users

As we explained earlier, we can revoke a certain permission prepending it with the minus sign and indicating whether it needs to be revoked for the owner, the group owner, or all users. The one-liner below can be interpreted as follows: Change mode for all (a) users, revoke (–) execute permission (x).

# chmod a-x backup.sh

Granting read, write, and execute permissions for a file to the owner and group owner, and read permissions for the world.

When we use a 3-digit octal number to set permissions for a file, the first digit indicates the permissions for the owner, the second digit for the group owner and the third digit for everyone else:

-

Owner: (r=22 + w=21 + x=20 = 7)

-

Group owner: (r=22 + w=21 + x=20 = 7)

-

World: (r=22 + w=0 + x=0 = 4),

chmod 774 myfile

In time, and with practice, you will be able to decide which method to change a file mode works best for you in each case. A long directory listing also shows the file’s owner and its group owner (which serve as a rudimentary yet effective access control to files in a system):

Linux File Listing

File ownership is changed with the chown command. The owner and the group owner can be changed at the same time or separately. Its basic syntax is as follows:

# chown user:group file

Where at least user or group need to be present.

Few Examples

Changing the owner of a file to a certain user.

# chown gacanepa sent

Changing the owner and group of a file to an specific user:group pair.

# chown gacanepa:gacanepa TestFile

Changing only the group owner of a file to a certain group. Note the colon before the group’s name.

# chown :gacanepa email_body.txt

Conclusion

As a sysadmin, you need to know how to create and restore backups, how to find files in your system and change their attributes, along with a few tricks that can make your life easier and will prevent you from running into future issues.

I hope that the tips provided in the present article will help you to achieve that goal. Feel free to add your own tips and ideas in the comments section for the benefit of the community. Thanks in advance! Reference Links

via: http://www.tecmint.com/compress-files-and-finding-files-in-linux/

作者:Gabriel Cánepa 译者:译者ID 校对:校对者ID