25 KiB

How writers can get work done better with Git

If you're a writer, you could probably benefit from using Git. Learn how

in our series about little-known uses of Git.

Git is one of those rare applications that has managed to encapsulate so much of modern computing into one program that it ends up serving as the computational engine for many other applications. While it's best-known for tracking source code changes in software development, it has many other uses that can make your life easier and more organized. In this series leading up to Git's 14th anniversary on April 7, we'll share seven little-known ways to use Git. Today, we'll look at ways writers can use Git to get work done.

Git for writers

Some people write fiction; others write academic papers, poetry, screenplays, technical manuals, or articles about open source. Many do a little of each. The common thread is that if you're a writer, you could probably benefit from using Git. While Git is famously a highly technical tool used by computer programmers, it's ideal for the modern author, and this article will demonstrate how it can change the way you write—and why you'd want it to.

Before talking about Git, though, it's important to talk about what copy (or content , for the digital age) really is, and why it's different from your delivery medium. It's the 21 st century, and the tool of choice for most writers is a computer. While computers are deceptively good at combining processes like copy editing and layout, writers are (re)discovering that separating content from style is a good idea, after all. That means you should be writing on a computer like it's a typewriter, not a word processor. In computer lingo, that means writing in plaintext.

Writing in plaintext

It used to be a safe assumption that you knew what market you were writing for. You wrote content for a book, or a website, or a software manual. These days, though, the market's flattened: you might decide to use content you write for a website in a printed book project, and the printed book might release an EPUB version later. And in the case of digital editions of your content, the person reading your content is in ultimate control: they may read your words on the website where you published them, or they might click on Firefox's excellent Reader View, or they might print to physical paper, or they could dump the web page to a text file with Lynx, or they may not see your content at all because they use a screen reader.

It makes sense to write your words as words, leaving the delivery to the publishers. Even if you are also your own publisher, treating your words as a kind of source code for your writing is a smarter and more efficient way to work, because when it comes time to publish, you can use the same source (your plaintext) to generate output appropriate to your target (PDF for print, EPUB for e-books, HTML for websites, and so on).

Writing in plaintext not only means you don't have to worry about layout or how your text is styled, but you also no longer require specialized tools. Anything that can produce text becomes a valid "word processor" for you, whether it's a basic notepad app on your mobile or tablet, the text editor that came bundled with your computer, or a free editor you download from the internet. You can write on practically any device, no matter where you are or what you're doing, and the text you produce integrates perfectly with your project, no modification required.

And, conveniently, Git specializes in managing plaintext.

The Atom editor

When you write in plaintext, a word processor is overkill. Using a text editor is easier because text editors don't try to "helpfully" restructure your input. It lets you type the words in your head onto the screen, no interference. Better still, text editors are often designed around a plugin architecture, such that the application itself is woefully basic (it edits text), but you can build an environment around it to meet your every need.

A great example of this design philosophy is the Atom editor. It's a cross-platform text editor with built-in Git integration. If you're new to working in plaintext and new to Git, Atom is the easiest way to get started.

Install Git and Atom

First, make sure you have Git installed on your system. If you run Linux or BSD, Git is available in your software repository or ports tree. The command you use will vary depending on your distribution; on Fedora, for instance:

`$ sudo dnf install git`

You can also download and install Git for Mac and Windows.

You won't need to use Git directly, because Atom serves as your Git interface. Installing Atom is the next step.

If you're on Linux, install Atom from your software repository through your software installer or the appropriate command, such as:

`$ sudo dnf install atom`

Atom does not currently build on BSD. However, there are very good alternatives available, such as GNU Emacs. For Mac and Windows users, you can find installers on the Atom website.

Once your installs are done, launch the Atom editor.

A quick tour

If you're going to live in plaintext and Git, you need to get comfortable with your editor. Atom's user interface may be more dynamic than what you are used to. You can think of it more like Firefox or Chrome than as a word processor, in fact, because it has tabs and panels that can be opened and closed as they are needed, and it even has add-ons that you can install and configure. It's not practical to try to cover all of Atom's many features, but you can at least get familiar with what's possible.

When Atom opens, it displays a welcome screen. If nothing else, this screen is a good introduction to Atom's tabbed interface. You can close the welcome screens by clicking the "close" icons on the tabs at the top of the Atom window and create a new file using File > New File.

Working in plaintext is a little different than working in a word processor, so here are some tips for writing content in a way that a human can connect with and that Git and computers can parse, track, and convert.

Write in Markdown

These days, when people talk about plaintext, mostly they mean Markdown. Markdown is more of a style than a format, meaning that it intends to provide a predictable structure to your text so computers can detect natural patterns and convert the text intelligently. Markdown has many definitions, but the best technical definition and cheatsheet is on CommonMark's website.

# Chapter 1

This is a paragraph with an *italic* word and a **bold** word in it.

And it can even reference an image.

As you can tell from the example, Markdown isn't meant to read or feel like code, but it can be treated as code. If you follow the expectations of Markdown defined by CommonMark, then you can reliably convert, with just one click of a button, your writing from Markdown to .docx, .epub, .html, MediaWiki, .odt, .pdf, .rtf, and a dozen other formats without loss of formatting.

You can think of Markdown a little like a word processor's styles. If you've ever written for a publisher with a set of styles that govern what chapter titles and section headings look like, this is basically the same thing, except that instead of selecting a style from a drop-down menu, you're adding little notations to your text. These notations look natural to any modern reader who's used to "txt speak," but are swapped out with fancy text stylings when the text is rendered. It is, in fact, what word processors secretly do behind the scenes. The word processor shows bold text, but if you could see the code generated to make your text bold, it would be a lot like Markdown (actually it's the far more complex XML). With Markdown, that barrier is removed, which looks scarier on the one hand, but on the other hand, you can write Markdown on literally anything that generates text without losing any formatting information.

The popular file extension for Markdown files is .md. If you're on a platform that doesn't know what a .md file is, you can associate the extension to Atom manually or else just use the universal .txt extension. The file extension doesn't change the nature of the file; it just changes how your computer decides what to do with it. Atom and some platforms are smart enough to know that a file is plaintext no matter what extension you give it.

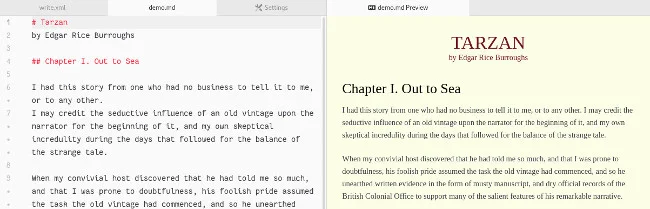

Live preview

Atom features the Markdown Preview plugin, which shows you both the plain Markdown you're writing and the way it will (commonly) render.

To activate this preview pane, select Packages > Markdown Preview > Toggle Preview or press Ctrl+Shift+M.

This view provides you with the best of both worlds. You get to write without the burden of styling your text, but you also get to see a common example of what your text will look like, at least in a typical digital format. Of course, the point is that you can't control how your text is ultimately rendered, so don't be tempted to adjust your Markdown to force your render preview to look a certain way.

One sentence per line

Your high school writing teacher doesn't ever have to see your Markdown.

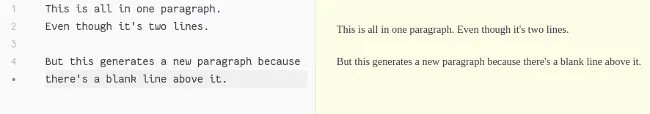

It won't come naturally at first, but maintaining one sentence per line makes more sense in the digital world. Markdown ignores single line breaks (when you've pressed the Return or Enter key) and only creates a new paragraph after a single blank line.

The advantage of writing one sentence per line is that your work is easier to track. That is, if you've changed one word at the start of a paragraph, then it's easy for Atom, Git, or any application to highlight that change in a meaningful way if the change is limited to one line rather than one word in a long paragraph. In other words, a change to one sentence should only affect that sentence, not the whole paragraph.

You might be thinking, "many word processors track changes, too, and they can highlight a single word that's changed." But those revision trackers are bound to the interface of that word processor, which means you can't look through revisions without being in front of that word processor. In a plaintext workflow, you can review revisions in plaintext, which means you can make or approve edits no matter what you have on hand, as long as that device can deal with plaintext (and most of them can).

Writers admittedly don't usually think in terms of line numbers, but it's a useful tool for computers, and ultimately a great reference point in general. Atom numbers the lines of your text document by default. A line is only a line once you have pressed the Enter or Return key.

If a line has a dot instead of a number, that means it's part of the previous line wrapped for you because it couldn't fit on your screen.

Theme it

If you're a visual person, you might be very particular about the way your writing environment looks. Even if you are writing in plain Markdown, it doesn't mean you have to write in a programmer's font or in a dark window that makes you look like a coder. The simplest way to modify what Atom looks like is to use theme packages. It's conventional for theme designers to differentiate dark themes from light themes, so you can search with the keyword Dark or Light, depending on what you want.

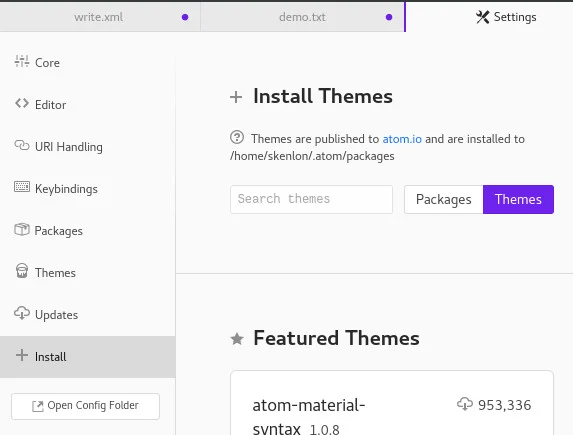

To install a theme, select Edit > Preferences. This opens a new tab in the Atom interface. Yes, tabs are used for your working documents and for configuration and control panels. In the Settings tab, click on the Install category.

In the Install panel, search for the name of the theme you want to install. Click the Themes button on the right of the search field to search only for themes. Once you've found your theme, click its Install button.

To use a theme you've installed or to customize a theme to your preference, navigate to the Themes category in your Settings tab. Pick the theme you want to use from the drop-down menu. The changes take place immediately, so you can see exactly how the theme affects your environment.

You can also change your working font in the Editor category of the Settings tab. Atom defaults to monospace fonts, which are generally preferred by programmers. But you can use any font on your system, whether it's serif or sans or gothic or cursive. Whatever you want to spend your day staring at, it's entirely up to you.

On a related note, by default Atom draws a vertical marker down its screen as a guide for people writing code. Programmers often don't want to write long lines of code, so this vertical line is a reminder to them to simplify things. The vertical line is meaningless to writers, though, and you can remove it by disabling the wrap-guide package.

To disable the wrap-guide package, select the Packages category in the Settings tab and search for wrap-guide. When you've found the package, click its Disable button.

Dynamic structure

When creating a long document, I find that writing one chapter per file makes more sense than writing an entire book in a single file. Furthermore, I don't name my chapters in the obvious syntax chapter-1.md or 1.example.md , but by chapter titles or keywords, such as example.md. To provide myself guidance in the future about how the book is meant to be assembled, I maintain a file called toc.md (for "Table of Contents") where I list the (current) order of my chapters.

I do this because, no matter how convinced I am that chapter 6 just couldn't possibly happen before chapter 1, there's rarely a time that I don't swap the order of one or two chapters or sections before I'm finished with a book. I find that keeping it dynamic from the start helps me avoid renaming confusion, and it also helps me treat the material less rigidly.

Git in Atom

Two things every writer has in common is that they're writing for keeps and their writing is a journey. You don't sit down to write and finish with a final draft; by definition, you have a first draft. And that draft goes through revisions, each of which you carefully save in duplicate and triplicate just in case one of your files turns up corrupted. Eventually, you get to what you call a final draft, but more than likely you'll be going back to it one day, either to resurrect the good parts or to fix the bad.

The most exciting feature in Atom is its strong Git integration. Without ever leaving Atom, you can interact with all of the major features of Git, tracking and updating your project, rolling back changes you don't like, integrating changes from a collaborator, and more. The best way to learn it is to step through it, so here's how to use Git within the Atom interface from the beginning to the end of a writing project.

First thing first: Reveal the Git panel by selecting View > Toggle Git Tab. This causes a new tab to open on the right side of Atom's interface. There's not much to see yet, so just keep it open for now.

Starting a Git project

You can think of Git as being bound to a folder. Any folder outside a Git directory doesn't know about Git, and Git doesn't know about it. Folders and files within a Git directory are ignored until you grant Git permission to keep track of them.

You can create a Git project by creating a new project folder in Atom. Select File > Add Project Folder and create a new folder on your system. The folder you create appears in the left Project Panel of your Atom window.

Git add

Right-click on your new project folder and select New File to create a new file in your project folder. If you have files you want to import into your new project, right-click on the folder and select Show in File Manager to open the folder in your system's file viewer (Dolphin or Nautilus on Linux, Finder on Mac, Explorer on Windows), and then drag-and-drop your files.

With a project file (either the empty one you created or one you've imported) open in Atom, click the Create Repository button in the Git tab. In the pop-up dialog box, click Init to initialize your project directory as a local Git repository. Git adds a .git directory (invisible in your system's file manager, but visible to you in Atom) to your project folder. Don't be fooled by this: The .git directory is for Git to manage, not you, so you'll generally stay out of it. But seeing it in Atom is a good reminder that you're working in a project actively managed by Git; in other words, revision history is available when you see a .git directory.

In your empty file, write some stuff. You're a writer, so type some words. It can be any set of words you please, but remember the writing tips above.

Press Ctrl+S to save your file and it will appear in the Unstaged Changes section of the Git tab. That means the file exists in your project folder but has not yet been committed over to Git's purview. Allow Git to keep track of your file by clicking on the Stage All button in the top-right of the Git tab. If you've used a word processor with revision history, you can think of this step as permitting Git to record changes.

Git commit

Your file is now staged. All that means is Git is aware that the file exists and is aware that it has been changed since the last time Git was made aware of it.

A Git commit sends your file into Git's internal and eternal archives. If you're used to word processors, this is similar to naming a revision. To create a commit, enter some descriptive text in the Commit message box at the bottom of the Git tab. You can be vague or cheeky, but it's more useful if you enter useful information for your future self so that you know why the revision was made.

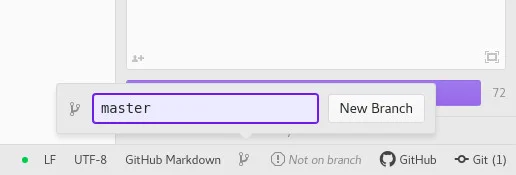

The first time you make a commit, you must create a branch. Git branches are a little like alternate realities, allowing you to switch from one timeline to another to make changes that you may or may not want to keep forever. If you end up liking the changes, you can merge one experimental branch into another, thereby unifying different versions of your project. It's an advanced process that's not worth learning upfront, but you still need an active branch, so you have to create one for your first commit.

Click on the Branch icon at the very bottom of the Git tab to create a new branch.

It's customary to name your first branch master. You don't have to; you can name it firstdraft or whatever you like, but adhering to the local customs can sometimes make talking about Git (and looking up answers to questions) a little easier because you'll know that when someone mentions master , they really mean master and not firstdraft or whatever you called your branch.

On some versions of Atom, the UI may not update to reflect that you've created a new branch. Don't worry; the branch will be created (and the UI updated) once you make your commit. Press the Commit button, whether it reads Create detached commit or Commit to master.

Once you've made a commit, the state of your file is preserved forever in Git's memory.

History and Git diff

A natural question is how often you should make a commit. There's no one right answer to that. Saving a file with Ctrl+S and committing to Git are two separate processes, so you will continue to do both. You'll probably want to make commits whenever you feel like you've done something significant or are about to try out a crazy new idea that you may want to back out of.

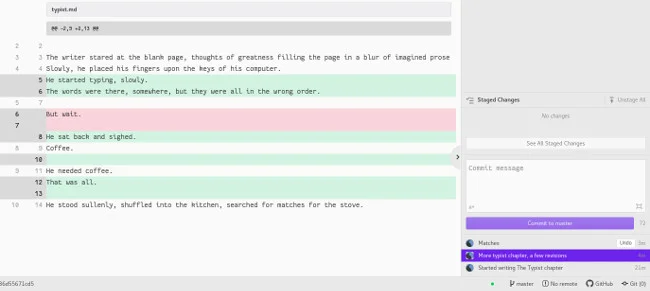

To get a feel for what impact a commit has on your workflow, remove some text from your test document and add some text to the top and bottom. Make another commit. Do this a few times until you have a small history at the bottom of your Git tab, then click on a commit to view it in Atom.

When viewing a past commit, you see three elements:

- Text in green was added to a document when the commit was made.

- Text in red was removed from the document when the commit was made.

- All other text was untouched.

Remote backup

One of the advantages of using Git is that, by design, it is distributed, meaning you can commit your work to your local repository and push your changes out to any number of servers for backup. You can also pull changes in from those servers so that whatever device you happen to be working on always has the latest changes.

For this to work, you must have an account on a Git server. There are several free hosting services out there, including GitHub, the company that produces Atom but oddly is not open source, and GitLab, which is open source. Preferring open source to proprietary, I'll use GitLab in this example.

If you don't already have a GitLab account, sign up for one and start a new project. The project name doesn't have to match your project folder in Atom, but it probably makes sense if it does. You can leave your project private, in which case only you and anyone you give explicit permissions to can access it, or you can make it public if you want it to be available to anyone on the internet who stumbles upon it.

Do not add a README to the project.

Once the project is created, it provides you with instructions on how to set up the repository. This is great information if you decide to use Git in a terminal or with a separate GUI, but Atom's workflow is different.

Click the Clone button in the top-right of the GitLab interface. This reveals the address you must use to access the Git repository. Copy the SSH address (not the https address).

In Atom, click on your project's .git directory and open the config. Add these configuration lines to the file, adjusting the seth/example.git part of the url value to match your unique address.

[remote "origin"]

url = [git@gitlab.com][16]:seth/example.git

fetch = +refs/heads/*:refs/remotes/origin/*

[branch "master"]

remote = origin

merge = refs/heads/master

At the bottom of the Git tab, a new button has appeared, labeled Fetch. Since your server is brand new and therefore has no data for you to fetch, right-click on the button and select Push. This pushes your changes to your Gitlab account, and now your project is backed up on a Git server.

Pushing changes to a server is something you can do after each commit. It provides immediate offsite backup and, since the amount of data is usually minimal, it's practically as fast as a local save.

Writing and Git

Git is a complex system, useful for more than just revision tracking and backups. It enables asynchronous collaboration and encourages experimentation. This article has covered the basics, but there are many more articles—and entire books—on Git and how to use it to make your work more efficient, more resilient, and more dynamic. It all starts with using Git for small tasks. The more you use it, the more questions you'll find yourself asking, and eventually the more tricks you'll learn.

via: https://opensource.com/article/19/4/write-git

作者:Seth Kenlon 选题:lujun9972 译者:译者ID 校对:校对者ID