16 KiB

Translating by qhwdw

The mysterious case of the Linux Page Table Isolation patches

_tl;dr: _ there is presently an embargoed security bug impacting apparently all contemporary CPU architectures that implement virtual memory, requiring hardware changes to fully resolve. Urgent development of a software mitigation is being done in the open and recently landed in the Linux kernel, and a similar mitigation began appearing in NT kernels in November. In the worst case the software fix causes huge slowdowns in typical workloads. There are hints the attack impacts common virtualization environments including Amazon EC2 and Google Compute Engine, and additional hints the exact attack may involve a new variant of Rowhammer.

I don’t really care much for security issues normally, but I adore a little intrigue, and it seems anyone who would normally write about these topics is either somehow very busy, or already knows the details and isn’t talking, which leaves me with a few hours on New Years’ Day to go digging for as much information about this mystery as I could piece together.

Beware this is very much a connecting-the-invisible-dots type affair, so it mostly represents guesswork until such times as the embargo is lifted. From everything I’ve seen, including the vendors involved, many fireworks and much drama is likely when that day arrives.

LWN

The trail begins with LWN’s current state of kernel page-table isolation article posted on December 20th. It’s apparent from the tone that a great deal of urgent work by the core kernel developers has been poured into the KAISER patch series first posted in October by a group of researchers from TU Graz in Austria.

The purpose of the series is conceptually simple: to prevent a variety of attacks by unmapping as much of the Linux kernel from the process page table while the process is running in user space, greatly hindering attempts to identify kernel virtual address ranges from unprivileged userspace code.

The group’s paper describing KAISER, KASLR is Dead: Long Live KASLR, makes specific reference in its abstract to removing all knowledge of kernel address space from the memory management hardware while user code is active on the CPU.

Of particular interest with this patch set is that it touches a core, wholly fundamental pillar of the kernel (and its interface to userspace), and that it is obviously being rushed through with the greatest priority. When reading about memory management changes in Linux, usually the first reference to a change happens long before the change is ever merged, and usually after numerous rounds of review, rejection and flame war spanning many seasons and moon phases.

The KAISER (now KPTI) series was merged in some time less than 3 months.

Recap: ASLR

On the surface, the patches appear designed to ensure Address Space Layout Randomization remains effective: this is a security feature of modern operating systems that attempts to introduce as many random bits as possible into the address ranges for commonly mapped objects.

For example, on invoking /usr/bin/python, the dynamic linker will arrange for the system C library, heap, thread stack and main executable to all receive randomly assigned address ranges:

$ bash -c ‘grep heap /proc/$$/maps’ 019de000-01acb000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [heap] $ bash -c 'grep heap /proc/$$/maps’ 023ac000-02499000 rw-p 00000000 00:00 0 [heap]

Notice how the start and end offset for the bash process heap changes across runs.

The effect of this feature is that, should a buffer management bug lead to an attacker being able to overwrite some memory address pointing at program code, and that address should later be used in program control flow, such that the attacker can divert control flow to a buffer containing contents of their choosing, it becomes much more difficult for the attacker to populate the buffer with machine code that would lead to, for example, the system() C library function being invoked, as the address of that function varies across runs.

This is a simple example, ASLR is designed to protect many similar such scenarios, including preventing the attacker from learning the addresses of program data that may be useful for modifying control flow or implementing an attack.

KASLR is “simply” ASLR applied to the kernel itself: on each reboot of the system, address ranges belonging to the kernel are randomized such that an attacker who manages to divert control flow while running in kernel mode cannot guess addresses for functions and structures necessary for implementing their attack, such as locating the current process data, and flipping the active UID from an unprivileged user to root, etc.

Bad news: the software mitigation is expensive

The primary reason for the old Linux behaviour of mapping kernel memory in the same page tables as user memory is so that when the user’s code triggers a system call, fault, or an interrupt fires, it is not necessary to change the virtual memory layout of the running process.

Since it is unnecessary to change the virtual memory layout, it is further unnecessary to flush highly performance-sensitive CPU caches that are dependant on that layout, primarily the Translation Lookaside Buffer.

With the page table splitting patches merged, it becomes necessary for the kernel to flush these caches every time the kernel begins executing, and every time user code resumes executing. For some workloads, the effective total loss of the TLB lead around every system call leads to highly visible slowdowns: @grsecurity measured a simple case where Linux “du -s” suffered a 50% slowdown on a recent AMD CPU.

34C3

Over at this year’s CCC, you can find another of the TU Graz researchers describing a pure-Javascript ASLR attack that works by carefully timing the operation of the CPU memory management unit as it traverses the page tables that describe the layout of virtual memory. The effect is that through a combination of high precision timing and selective eviction of CPU cache lines, a Javascript program running in a web browser can recover the virtual address of a Javascript object, enabling subsequent attacks against browser memory management bugs.

So again, on the surface, we have a group authoring the KAISER patches also demonstrating a technique for unmasking ASLR’d addresses, and the technique, demonstrated using Javascript, is imminently re-deployable against an operating system kernel.

Recap: Virtual Memory

In the usual case, when some machine code attempts to load, store, or jump to a memory address, modern CPUs must first translate this virtual address to a physical address, by way of walking a series of OS-managed arrays (called page tables) that describe a mapping between virtual memory and physical RAM installed in the machine.

Virtual memory is possibly the single most important robustness feature in modern operating systems: it is what prevents, for example, a dying process from crashing the operating system, a web browser bug crashing your desktop environment, or one virtual machine running in Amazon EC2 from effecting changes to another virtual machine on the same host.

The attack works by exploiting the fact that the CPU maintains numerous caches, and by carefully manipulating the contents of these caches, it is possible to infer which addresses the memory management unit is accessing behind the scenes as it walks the various levels of page tables, since an uncached access will take longer (in real time) than a cached access. By detecting which elements of the page table are accessed, it is possible to recover the majority of the bits in the virtual address the MMU was busy resolving.

Evidence for motivation, but not panic

We have found motivation, but so far we have not seen anything to justify the sheer panic behind this work. ASLR in general is an imperfect mitigation and very much a last line of defence: there is barely a 6 month period where even a non-security minded person can read about some new method for unmasking ASLR’d pointers, and reality has been this way for as long as ASLR has existed.

Fixing ASLR alone is not sufficient to describe the high priority motivation behind the work.

Evidence: it’s a hardware security bug

From reading through the patch series, a number of things are obvious.

First of all, as @grsecurity points out, some comments in the code have been redacted, and additionally the main documentation file describing the work is presently missing entirely from the Linux source tree.

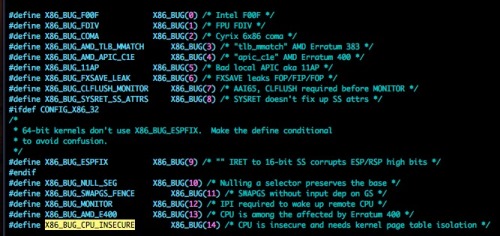

Examining the code, it is structured in the form of a runtime patch applied at boot only when the kernel detects the system is impacted, using exactly the same mechanism that, for example, applies mitigations for the infamous Pentium F00F bug:

More clues: Microsoft have also implemented page table splitting

From a little digging through the FreeBSD source tree, it seems that so far other free operating systems are not implementing page table splitting, however as noted by Alex Ioniscu on Twitter, the work already is not limited to Linux: public NT kernels from as early as November have begun to implement the same technique.

Guesswork: Rowhammer

Digging further into the work of the researchers at TU Graz, we find When rowhammer only knocks once, an announcement on December 4th of a new variant of the Rowhammer attack:

In this paper, we present novel Rowhammer attack and exploitation primitives, showing that even a combination of all defenses is ineffective. Our new attack technique, one-location hammering, breaks previous assumptions on requirements for triggering the Rowhammer bug

As a quick recap, Rowhammer is a class of problem fundamental to most (all?) kinds of commodity DRAMs, such as the memory in the average computer. Through precise manipulation of one area of memory, it is possible to cause degradation of storage in a related (but otherwise logically distinct) area of memory. The effect is that Rowhammer can be used to flip bits of memory that unprivileged user code should have no access to, such as bits describing how much access that code should have to the rest of the system.

I found this work on Rowhammer particularly interesting, not least for its release being in such close proximity to the page table splitting patches, but because Rowhammer attacks require a target: you must know the physical address of the memory you are attempting to mutate, and a first step to learning a physical address may be learning a virtual address, such as in the KASLR unmasking work.

Guesswork: it effects major cloud providers

On the kernel mailing list we can see, in addition to the names of subsystem maintainers, e-mail addresses belonging to employees of Intel, Amazon and Google. The presence of the two largest cloud providers is particularly interesting, as this provides us with a strong clue that the work may be motivated in large part by virtualization security.

Which leads to even more guessing: virtual machine RAM, and the virtual memory addresses used by those virtual machines are ultimately represented as large contiguous arrays on the host machine, arrays that, especially in the case of only 2 tenants on a host machine, are assigned by memory allocators in the Xen and Linux kernels that likely have very predictable behaviour.

Favourite guess: it is a privilege escalation attack against hypervisors

Putting it all together, I would not be surprised if we start 2018 with the release of the mother of all hypervisor privilege escalation bugs, or something similarly systematic as to drive so much urgency, and the presence of so many interesting names on the patch set’s CC list.

One final tidbit, while I’ve lost my place reading through the patches, there is some code that specifically marked either paravirtual or HVM Xen as unaffected.

Invest in popcorn, 2018 is going to be fun

It’s totally possible this guess is miles off reality, but one thing is for sure, it’s going to be an exciting few weeks when whatever this thing is published.

via: http://pythonsweetness.tumblr.com/post/169166980422/the-mysterious-case-of-the-linux-page-table

作者:python sweetness 译者:译者ID 校对:校对者ID