14 KiB

10 eureka moments of coding in the community

We asked our community to share about a time they sat down and wrote

code that truly made them proud.

If you've written code, you know it takes practice to get good at it. Whether it takes months or years, there's inevitably a moment of epiphany.

We wanted to hear about that time, so we asked our community to share about that time they sat down and wrote code that truly made them proud.

One of mine around coding goes back to college in the 70s. I learned about parsing arithmetic expressions and putting them into Reverse Polish notation. And then, I figured out that, just like multiplication is repeated addition, division is repeated subtraction. But you can make it quicker by starting with an appropriate power of 10. And with that, I wrote a BASIC Plus program on a 16-bit PDP 11/45 running RSTS to do multi-precision arithmetic. And then, I added a bunch of subroutines for various calculations. I tested it by calculating PI to 45 digits. It ran for a half-hour but worked. I may have saved it to DECtape. —Greg Scott

In the mid-1990s, I worked as part of a small consulting team (three programmers) on production planning and scheduling for a large steel company. The app was to be delivered on Hewlett-Packard workstations (then quite the thing), and the GUI was to be done in XWindows. To our amazement, it was CommonLisp that came out with the first decent interface to Motif, which had (for the time) a very nice widget toolkit. As a result, the entire app was done in CommonLisp and performed acceptably on the workstations. It was great fun to do something commercial in Lisp.

As you might guess, the company then wanted to port from the Hewlett-Packard workstations to something cheap, and so, about four years later, we rewrote the app in C with the expected boost in performance. —Marty Kalin

This topic brought an old memory back. Though I got many moments of self-satisfaction from writing the first C program to print a triangle to writing a validating admission webhook and operators for Kubernetes from scratch.

For a long time, I saw and played games written in various languages, and so I had an irresistible itch to write a few possible games using bash shell script.

I wrote the first one, tic-tac-toe and then Minesweeper, but they never got published until a couple of years back, when I committed them to GitHub, and people started liking them.

I was glad to get an opportunity to have the article published on this website. —Abhishek Tamrakar

Although there've been other, more recent works, two rather long-in-the-tooth bits of a doggerel leap to mind, mostly because of the "Eureka!" moments when I was able to examine the output and verify that I had indeed understood the Rosetta Stones I was working with enough to decipher the cryptic data:

- UNPAL: A cross-disassembler written in the DECsystem-10's MACRO-10 assembly language. It would take PDP-11 binaries and convert them back to the PDP-11 MACRO-11 assembler language. Many kudos to the folks writing the documentation back then, particularly, the DEC-10's 17 or so volumes, filled with great information and a fair amount of humor. UNPAL made its way out into the world and is probably the only piece of code that was used by people outside of either my schools or my workplace. (On the other hand, some of my documentation/tutorials got spread around on lots of external mailing lists and websites.)

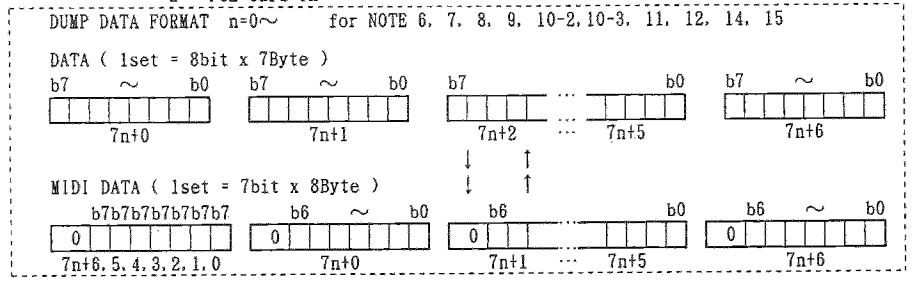

- MUNSTER: Written in a language I had not yet learned, for an operating system I had never encountered before, on a computer that I'd only heard of, for a synthesizer I knew nothing about, using cryptic documentation. The language was C, the machine, an Atari 1040-ST (? ST-1040?), the OS—I don't remember, but it had something to do with GEM? And the synthesizer, a Korg M1—hence the name "munster" (m1-ster). It was quite the learning experience, studying all of the components simultaneously. The code would dump and restore the memory of eight synthesizers in the music lab. The Korg manual failed (IMHO) to really explain the data format. The appendix was a maze of twisty little passages all alike, with lots of "Note 8: See note 14 in Table 5. Table 5, Note 14: See notes 3, 4, and 7 in Table 2." Eventually, I deciphered from a picture without any real explanation, that when dumping data, every set of seven 8-bit bytes was being converted to eight 7-bit bytes, by stripping the high-order bit from each of the seven bytes and prefixing the seven high-order bits into an extra byte preceding the seven stripped bytes. This had to be figured out from a tiny illustration in the appendix (see attached screenshot from the manual):

(Kevin Cole, CC BY-SA 4.0)

For me, it is definitively GSequencer's synchronization function AgsThread::clock().

Working with parallelism

During the development of GSequencer, I have encountered many obstacles. When I started the project, I was barely familiar with multi-threaded code execution. I was aware of pthread_create(), pthread_mutex_lock(), and pthread_mutex_unlock().

But what I needed was more complex synchronization functionality. There are mainly three choices available—conditional locks, barriers, and semaphores. I decided for conditional locks since it is available from GLib-2.0 threading API.

Conditional locks usually don't proceed with program flow until a condition within a loop turns to be FALSE. So in one thread, you do, for example:

gboolean start_wait;

gboolean start_done = FALSE;

static GCond cond;

static GMutex mutex;

/* conditional lock */

g_mutex_lock(&mutex);

if(!start_done){

start_wait = TRUE;

while(start_wait &&

!start_done){

g_cond_wait(&cond,

&mutex);

}

}

g_mutex_unlock(&mutex);

Within another thread, you can wake up the conditional lock, and if conditional evaluates to FALSE, the program flow proceeds for the waiting thread.

/* signal conditional lock */

g_mutex_lock(&mutex);

start_done = TRUE;

if(start_wait){

g_cond_signal(&cond);

}

g_mutex_unlock(&mutex);

Libags provides a thread wrapper built on top of GLib's threading API. The AgsThread object synchronizes the thread tree by AgsThread::clock() event. It is some kind of parallelism trap.

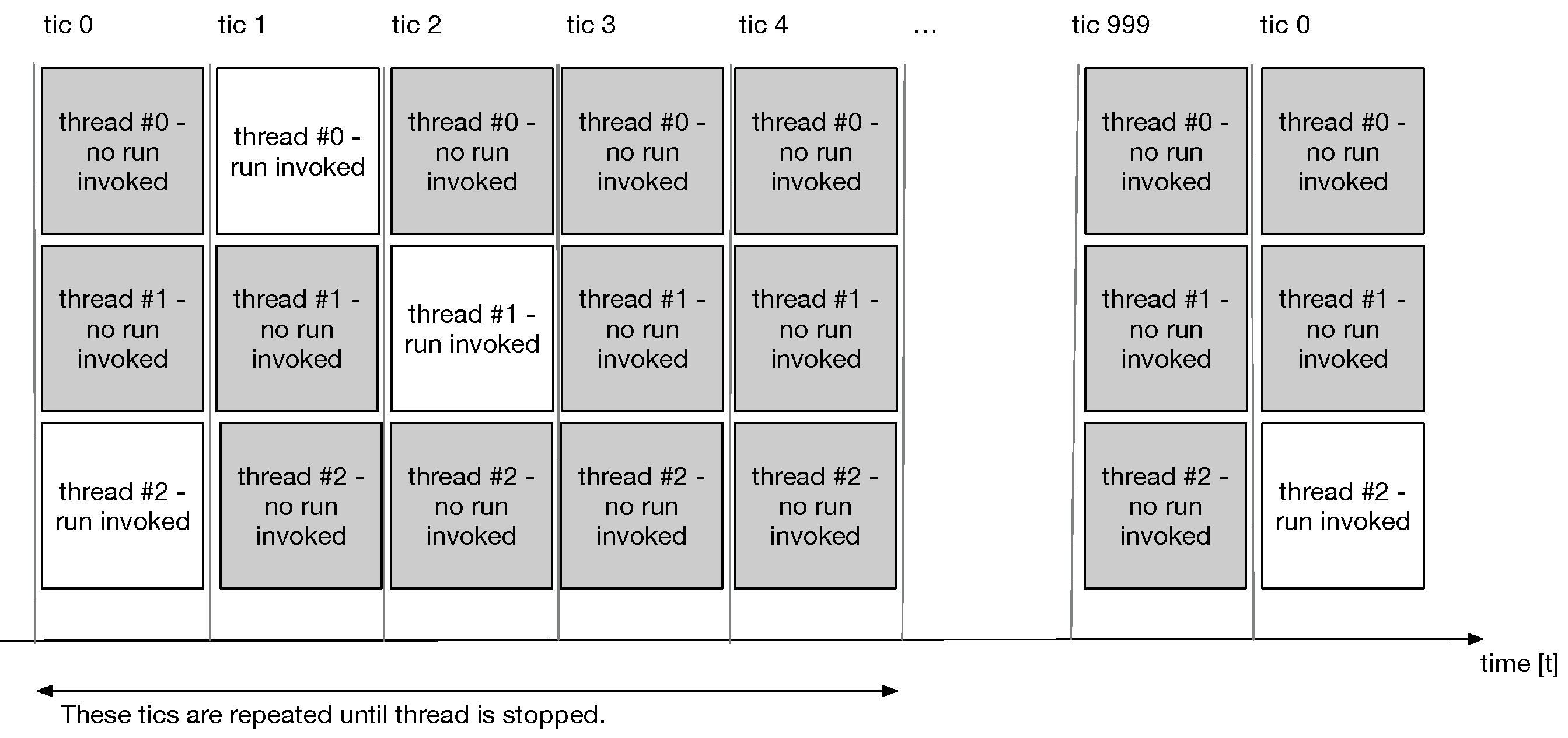

(Joel Krahemann, CC BY-SA 4.0)

All threads within the tree synchronize to AgsThread:max-precision per second because all threads shall have the very same time running in parallel. I talk of tic-based parallelism, with a max-precision of 1000 Hz, each thread synchronizes 1000 times within the tree—giving you strong semantics to compute a deterministic result in a multi-threaded fashion.

Since we want to run tasks exclusively without any interference from competing threads, there is a mutex lock involved just after synchronization and then invokes ags_task_launcher_sync_run(). Be aware the conditional lock can be evaluated to be true for many threads.

After how many tics the flow is repeated depends on sample rate and buffer size. If you have an AgsThread with max-precision 1000, the sample rate of 44100 common for audio CDs, and a buffer size of 512 frames, then the delay until it's repeated calculates as follows:

`tic_delay = 1000.0 / 44100.0 * 512.0; // 11.609977324263039`

As you might have pre-/post-synchronization needing three tics to do its work, you get eight unused tics.

Pre-synchronization is used for reading from a soundcard or MIDI device. The intermediate tic does the actual audio processing. Post-synchronization is used by outputting to the soundcard or exporting to an audio file.

To get this working, I went through heights and depths. This is especially because you can't hear or see a thread. GDB's batch debugging helped a lot. With batch debugging, you can retrieve a stack trace of a running process. —Joël Kräheman

I don't know that I've written any code to be particularly proud of—me being a neurodiverse programmer may mean my case is that I'm only an average programmer with specific strengths and weaknesses.

However, many years ago, I did some coding in C with basic examples in parallel virtual machines, which I was very happy when I got them working.

More than ten years ago, I had a programming course where I taught Java to adult students, and I'm happy that I was able to put that course together.

I'm recently happy that I managed to help college students with disabilities bug test code as a part-time job. —Rikard Grossman-Nielsen

Like others, this made me think back aways. I don't really consider myself a developer, but I have done some along the way. The thing that stuck out for me is the epiphany factor, or "moment of epiphany," as you said.

When I was a student at UNCW, I worked for the OIT network group managing the network for the dormitories. The students all received their IP address registrations using Bootstrap Protocol (BOOTP)—the predecessor to DHCP. The configuration file was maintained by hand in the beginning when we only had about 30 students. This was the very first year that the campus offered Internet to students! The next year, as more dorms got wired, the numbers grew and quickly reached over 200. I wrote a small C program to maintain the config file. The epiphany and "just plain old neat part" was that my code could touch and manipulate something "real" outside itself. In this case, a file on the system. I had a similar feeling later in a Java class when I learned how to read and write to a SQL server.

Anyway, there was something cool about seeing a real result from a program. One more amazing thing is that the original binary, which was compiled on a Red Hat 5.1 Linux system, will still run on my current Fedora 34 Linux desktop!! —Alan Formy-Duval

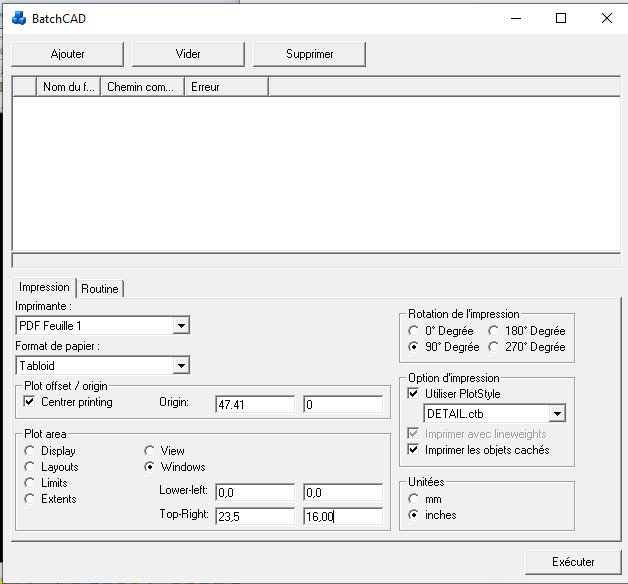

At the age of 18, I was certainly proud when I wrote a Virtual Basic application for a small company to automate printing AutoCAD files in bulk. At that time, it was the first "complex" application I wrote. Many user interactions were needed to configure the printer settings. In addition, the application was integrated with AutoCAD using Com ActiveX. It was challenging. The company kept using it until recently. The application stopped working because of an incompatibility issue with Windows 10. They used it for 18 years without issues!

I've been tasked to rewrite the application using today's technology. I've written the new version in Python. Looking back at the code I wrote was funny. It was so clumsy.

Attached is a screenshot of the first version.

(Patrik Dufresne, CC BY-SA 4.0)

I once integrated GitHub with the Open Humans platform, which was part of my Outreachy project back in 2019. That was my venture into Django, and I learned a lot about APIs and rate limits in the process.

Also, very recently, I started working with Quarkus and started building REST, GraphQl APIs with it. I found it really cool. —Manaswini Das

Around 1998, I got bored and decided to write a game. Inspired by an old Mac game from the 1980s, I decided to create a "simulation" game where the user constructed a simple "program" to control a virtual robot and then explore a maze. The environment was littered with prizes and energy pellets to power your robot—but also contained enemies that could damage your robot if it ran into them. I added an energy "cost" so that every time your robot moved or took any action, it used up a little bit of its stored energy. So you had to balance "picking up prizes" with "finding energy pellets." The goal was to pick up as many prizes before you ran out of energy.

I experimented with using GNU Guile (a Scheme extension language) as a programming "backend," which worked well, even though I don't really know Scheme. I figured out enough Scheme to write some interesting robot programs.

And that's how I wrote GNU Robots. It was just a quick thing to amuse myself, and it was fun to work on and fun to play. Later, other developers picked it up and ran with it, making major improvements to my simple code. It was so cool to rediscover a few years ago that you can still compile GNU Robots and play around with them. Congratulations to the new maintainers for keeping it going. —Jim Hall

via: https://opensource.com/article/21/11/community-code-stories

作者:Jen Wike Huger 选题:lujun9972 译者:译者ID 校对:校对者ID