18 KiB

Learning BASIC Like It's 1983

I was not yet alive in 1983. This is something that I occasionally regret. I am especially sorry that I did not experience the 8-bit computer era as it was happening, because I think the people that first encountered computers when they were relatively simple and constrained have a huge advantage over the rest of us.

Today, (almost) everyone knows how to use a computer, but very few people, even in the computing industry, grasp all of what is going on inside of any single machine. There are now so many layers of software doing so many different things that one struggles to identify the parts that are essential. In 1983, though, home computers were unsophisticated enough that a diligent person could learn how a particular computer worked through and through. That person is today probably less mystified than I am by all the abstractions that modern operating systems pile on top of the hardware. I expect that these layers of abstractions were easy to understand one by one as they were introduced; today, new programmers have to try to understand them all by working top to bottom and backward in time.

Many famous programmers, particularly in the video game industry, started programming games in childhood on 8-bit computers like the Apple II and the Commodore 64. John Romero, Richard Garriott, and Chris Roberts are all examples. It’s easy to see how this happened. In the 8-bit computer era, many games were available only as printed BASIC listings in computer magazines and books. If you wanted to play one of those games, you had to type in the whole program by hand. Inevitably, you would get something wrong, so you would have to debug your program. By the time you got it working, you knew enough about how the program functioned to start modifying it yourself. If you were an avid gamer, you became a good programmer almost by necessity.

I also played computer games throughout my childhood. But the games I played came on CD-ROMs. I sometimes found myself having to google how to fix a crashing installer, which would involve editing the Windows Registry or something like that. This kind of minor troubleshooting may have made me comfortable enough with computers to consider studying computer science in college. But it never taught me anything crucial about how computers worked or how to control them.

Now, of course, I tell computers what to do for a living. All the same, I can’t help feeling that I missed out on some fundamental insight afforded only to those that grew up programming simpler computers. What would it have been like to encounter computers for the first time in the early 1980s? How would that have been different from the experience of using a computer today?

This post is going to be a little different from the usual Two-Bit History post because I’m going to try to imagine an answer to these questions.

1983

It was just last week that you saw the Commodore 64 ad on TV. Now that MAS*H was over, you were in the market for something new to do on Monday nights. This Commodore 64 thing looked even better than the Apple II that Rudy’s family had in their basement. Plus, the ad promised that the new computer would soon bring friends “knocking down” your door. You knew several people at school that would rather be hanging out at your house than Rudy’s anyway, if only they could play Zork there.

So you persuaded your parents to buy one. Your mother said that they would consider it only if having a home computer meant that you stayed away from the arcade. You reluctantly agreed. Your father thought he would start tracking the family’s finances in MultiPlan, the spreadsheet program he had heard about, which is why the computer got put in the living room. A year later, though, you would be the only one still using it. You were finally allowed to put it on the desk in your bedroom, right under your Police poster.

(Your sister protested this decision, but it was 1983 and computers weren’t for her.)

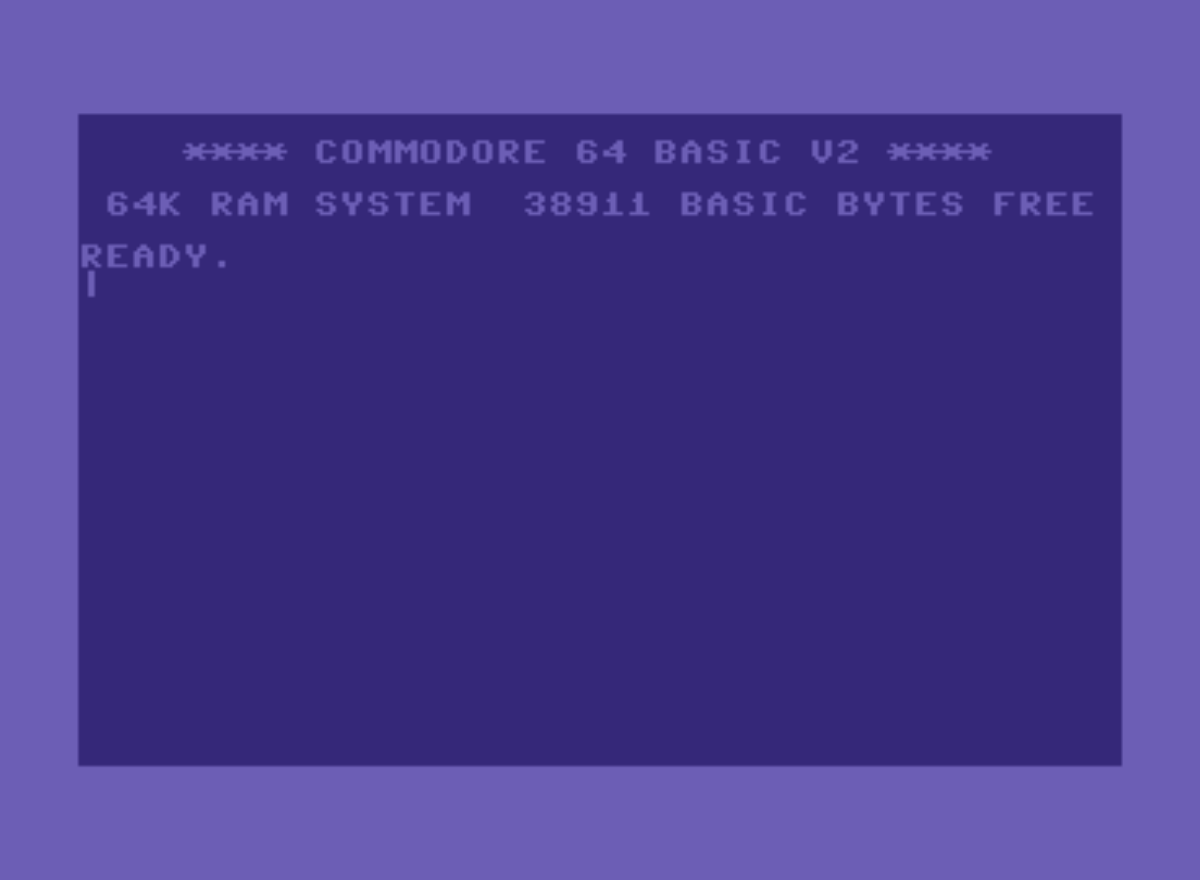

Dad picked it up from ComputerLand on the way home from work. The two of you laid the box down next to the TV and opened it. “WELCOME TO THE WORLD OF FRIENDLY COMPUTING,” said the packaging. Twenty minutes later, you weren’t convinced—the two of you were still trying to connect the Commodore to the TV set and wondering whether the TV’s antenna cable was the 75-ohm or 300-ohm coax type. But eventually you were able to turn your TV to channel 3 and see a grainy, purple image.

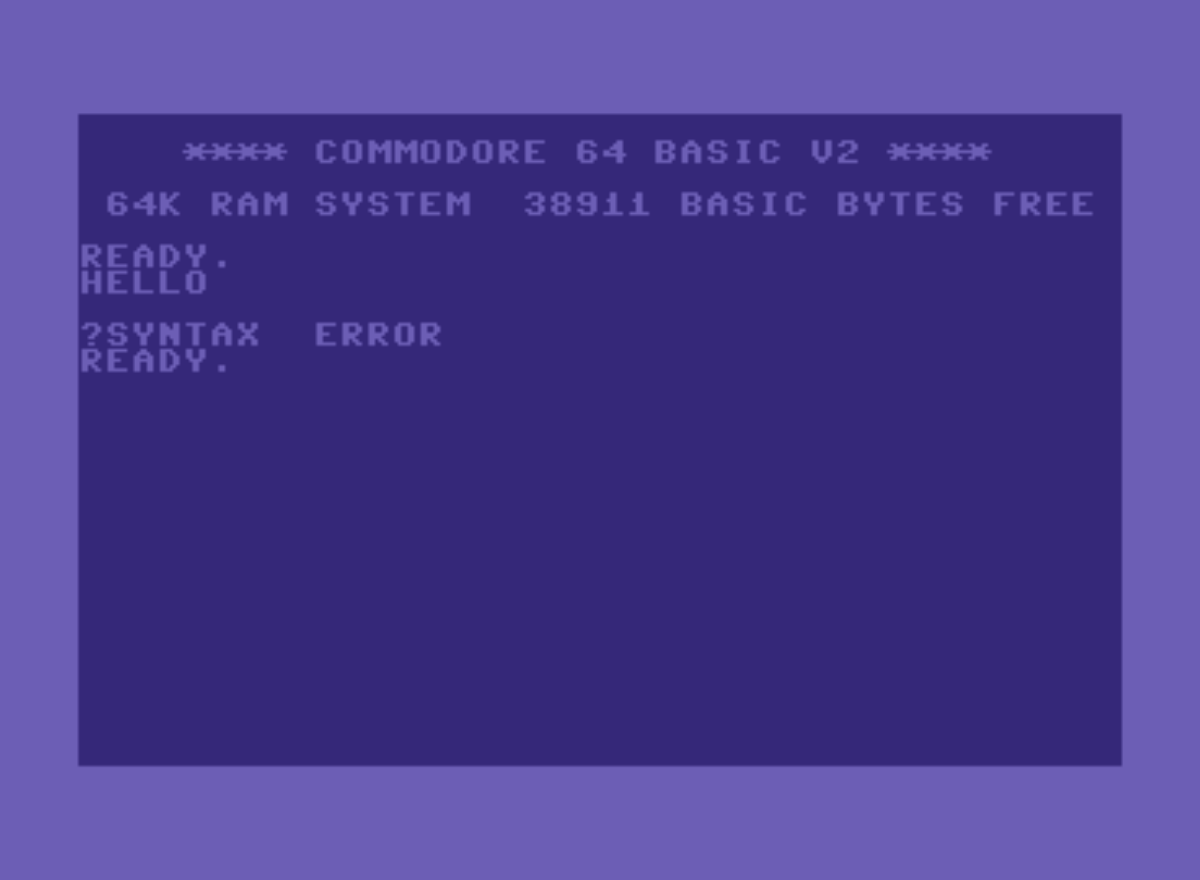

READY, the computer reported. Your father pushed the computer toward you, indicating that you should be the first to give it a try. HELLO, you typed, carefully hunting for each letter. The computer’s response was baffling.

You tried typing in a few different words, but the response was always the same. Your father said that you had better read through the rest of the manual. That would be no mean feat—the manual that came with the Commodore 64 was a small book. But that didn’t bother you, because the introduction to the manual foreshadowed wonders.

The Commodore 64, it claimed, had “the most advanced picture maker in the microcomputer industry,” which would allow you “to design your own pictures in four different colors, just like the ones you see on arcade type video games.” The Commodore 64 also had “built-in music and sound effects that rival many well known music synthesizers.” All of these tools would be put in your hands, because the manual would walk you through it all:

Just as important as all the available hardware is the fact that this USER’S GUIDE will help you develop your understanding of computers. It won’t tell you everything there is to know about computers, but it will refer you to a wide variety of publications for more detailed information about the topics presented. Commodore wants you to really enjoy your new COMMODORE 64. And to have fun, remember: programming is not the kind of thing you can learn in a day. Be patient with yourself as you go through the USER’S GUIDE.

That night, in bed, you read through the entire first three chapters—”Setup,” “Getting Started,” and “Beginning BASIC Programming”—before finally succumbing to sleep with the manual splayed across your chest.

Commodore BASIC

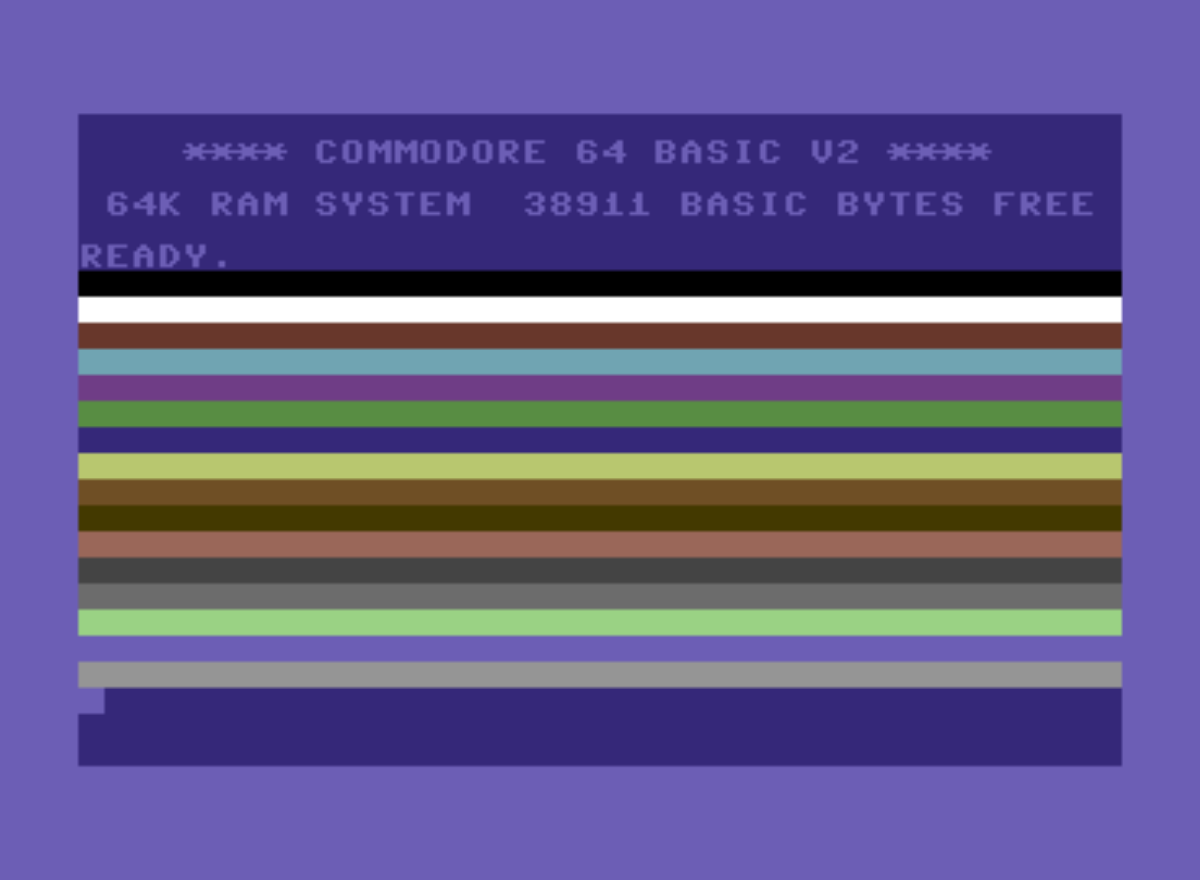

Now, it’s Saturday morning and you’re eager to try out what you’ve learned. One of the first things the manual teaches you how to do is change the colors on the display. You follow the instructions, pressing CTRL-9 to enter reverse type mode and then holding down the space bar to create long lines. You swap between colors using CTRL-1 through CTRL-8, reveling in your sudden new power over the TV screen.

As cool as this is, you realize it doesn’t count as programming. In order to program the computer, you learned last night, you have to speak to it in a language called BASIC. To you, BASIC seems like something out of Star Wars, but BASIC is, by 1983, almost two decades old. It was invented by two Dartmouth professors, John Kemeny and Tom Kurtz, who wanted to make computing accessible to undergraduates in the social sciences and humanities. It was widely available on minicomputers and popular in college math classes. It then became standard on microcomputers after Bill Gates and Paul Allen wrote the MicroSoft BASIC interpreter for the Altair. But the manual doesn’t explain any of this and you won’t learn it for many years.

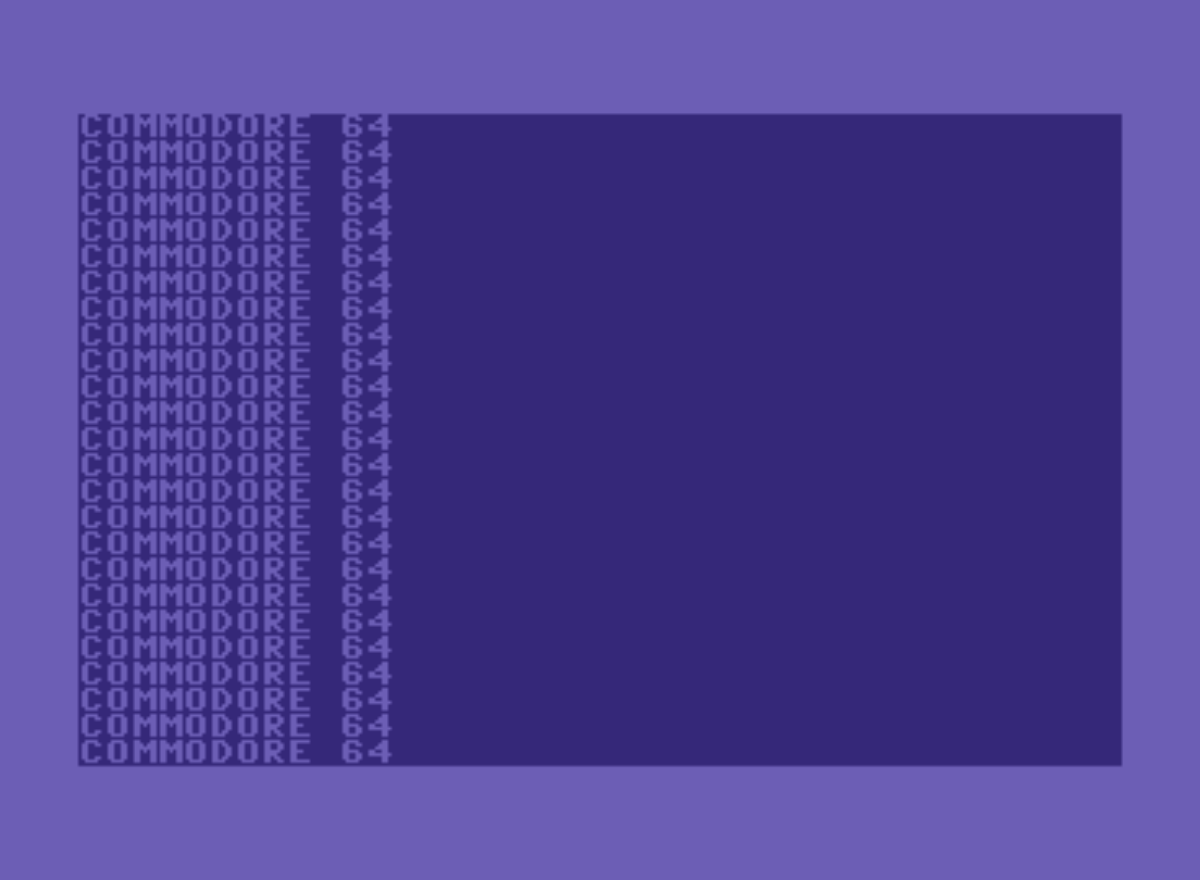

One of the first BASIC commands the manual suggests you try is the PRINT command. You type in PRINT "COMMODORE 64", slowly, since it takes you a while to find the quotation mark symbol above the 2 key. You hit RETURN and this time, instead of complaining, the computer does exactly what you told it to do and displays “COMMODORE 64” on the next line.

Now you try using the PRINT command on all sorts of different things: two numbers added together, two numbers multiplied together, even several decimal numbers. You stop typing out PRINT and instead use ?, since the manual has advised you that ? is an abbreviation for PRINT often used by expert programmers. You feel like an expert already, but then you remember that you haven’t even made it to chapter three, “Beginning BASIC Programming.”

You get there soon enough. The chapter begins by prompting you to write your first real BASIC program. You type in NEW and hit RETURN, which gives you a clean slate. You then type your program in:

10 ?"COMMODORE 64"

20 GOTO 10

The 10 and the 20, the manual explains, are line numbers. They order the statements for the computer. They also allow the programmer to refer to other lines of the program in certain commands, just like you’ve done here with the GOTO command, which directs the program back to line 10. “It is good programming practice,” the manual opines, “to number lines in increments of 10—in case you need to insert some statements later on.”

You type RUN and stare as the screen clogs with “COMMODORE 64,” repeated over and over.

You’re not certain that this isn’t going to blow up your computer. It takes you a second to remember that you are supposed to hit the RUN/STOP key to break the loop.

The next few sections of the manual teach you about variables, which the manual tells you are like “a number of boxes within the computer that can each hold a number or a string of text characters.” Variables that end in a % symbol are whole numbers, while variables ending in a $ symbol are strings of characters. All other variables are something called “floating point” variables. The manual warns you to be careful with variable names because only the first two letters of the name are actually recognized by the computer, even though nothing stops you from making a name as long as you want it to be. (This doesn’t particularly bother you, but you could see how 30 years from now this might strike someone as completely insane.)

You then learn about the IF... THEN... and FOR... NEXT... constructs. With all these new tools, you feel equipped to tackle the next big challenge the manual throws at you. “If you’re the ambitious type,” it goads, “type in the following program and see what happens.” The program is longer and more complicated than any you have seen so far, but you’re dying to know what it does:

10 REM BOUNCING BALL

20 PRINT "{CLR/HOME}"

25 FOR X = 1 TO 10 : PRINT "{CRSR/DOWN}" : NEXT

30 FOR BL = 1 TO 40

40 PRINT " ●{CRSR LEFT}";:REM (● is a Shift-Q)

50 FOR TM = 1 TO 5

60 NEXT TM

70 NEXT BL

75 REM MOVE BALL RIGHT TO LEFT

80 FOR BL = 40 TO 1 STEP -1

90 PRINT " {CRSR LEFT}{CRSR LEFT}●{CRSR LEFT}";

100 FOR TM = 1 TO 5

110 NEXT TM

120 NEXT BL

130 GOTO 20

The program above takes advantage of one of the Commodore 64’s coolest features. Non-printable command characters, when passed to the PRINT command as part of a string, just do the action they usually perform instead of printing to the screen. This allows you to replay arbitrary chains of commands by printing strings from within your programs.

It takes you a long time to type in the above program. You make several mistakes and have to re-enter some of the lines. But eventually you are able to type RUN and behold a masterpiece:

You think that this is a major contender for the coolest thing you have ever seen. You forget about it almost immediately though, because once you’ve learned about BASIC’s built-in functions like RND (which returns a random number) and CHR$ (which returns the character matching a given number code), the manual shows you a program that many years from now will still be famous enough to be made the title of an essay anthology:

10 PRINT "{CLR/HOME}"

20 PRINT CHR$(205.5 + RND(1));

40 GOTO 20

When run, the above program produces a random maze:

This is definitely the coolest thing you have ever seen.

PEEK and POKE

You’ve now made it through the first four chapters of the Commodore 64 manual, including the chapter titled “Advanced BASIC,” so you’re feeling pretty proud of yourself. You’ve learned a lot this Saturday morning. But this afternoon (after a quick lunch break), you’re going to learn something that will make this magical machine in your living room much less mysterious.

The next chapter in the manual is titled “Advanced Color and Graphic Commands.” It starts off by revisiting the colored bars that you were able to type out first thing this morning and shows you how you can do the same thing from a program. It then teaches you how to change the background colors of the screen.

In order to do this, you need to use the BASIC PEEK and POKE commands. Those commands allow you to, respectively, examine and write to a memory address. The Commodore 64 has a main background color and a border color. Each is controlled by a specially designated memory address. You can write any color value you would like to those addresses to make the background or border that color.

The manual explains:

Just as variables can be thought of as a representation of “boxes” within the machine where you placed your information, you can also think of some specially defined “boxes” within the computer that represent specific memory locations.

The Commodore 64 looks at these memory locations to see what the screen’s background and border color should be, what characters are to be displayed on the screen—and where—and a host of other tasks.

You write a program to cycle through all the available combinations of background and border color:

10 FOR BA = 0 TO 15

20 FOR BO = 0 TO 15

30 POKE 53280, BA

40 POKE 53281, BO

50 FOR X = 1 TO 500 : NEXT X

60 NEXT BO : NEXT BA

While the POKE commands, with their big operands, looked intimidating at first, now you see that the actual value of the number doesn’t matter that much. Obviously, you have to get the number right, but all the number represents is a “box” that Commodore just happened to store at address 53280. This box has a special purpose: Commodore uses it to determine what color the screen’s background should be.

You think this is pretty neat. Just by writing to a special-purpose box in memory, you can control a fundamental property of the computer. You aren’t sure how the Commodore 64’s circuitry takes the value you write in memory and changes the color of the screen, but you’re okay not knowing that. At least you understand everything up to that point.

Special Boxes

You don’t get through the entire manual that Saturday, since you are now starting to run out of steam. But you do eventually read all of it. In the process, you learn about many more of the Commodore 64’s special-purpose boxes. There are boxes you can write to control what is on screen—one box, in fact, for every place a character might appear. In chapter six, “Sprite Graphics,” you learn about the special-purpose boxes that allow you to define images that can be moved around and even scaled up and down. In chapter seven, “Creating Sound,” you learn about the boxes you can write to in order to make your Commodore 64 sing “Michael Row the Boat Ashore.” The Commodore 64, it turns out, has very little in the way of what you would later learn is called an API. Controlling the Commodore 64 mostly involves writing to memory addresses that have been given special meaning by the circuitry.

The many years you ultimately spend writing to those special boxes stick with you. Even many decades later, when you find yourself programming a machine with an extensive graphics or sound API, you know that, behind the curtain, the API is ultimately writing to those boxes or something like them. You will sometimes wonder about younger programmers that have only ever used APIs, and wonder what they must think the API is doing for them. Maybe they think that the API is calling some other, hidden API. But then what do think that hidden API is calling? You will pity those younger programmers, because they must be very confused indeed.

If you enjoyed this post, more like it come out every two weeks! Follow @TwoBitHistory on Twitter or subscribe to the RSS feed to make sure you know when a new post is out.

Previously on TwoBitHistory…

Have you ever wondered what a 19th-century computer program would look like translated into C?

This week's post: A detailed look at how Ada Lovelace's famous program worked and what it was trying to do.https://t.co/BizR2Zu7nt

— TwoBitHistory (@TwoBitHistory) August 19, 2018

via: https://twobithistory.org/2018/09/02/learning-basic.html

作者:Two-Bit History 选题:lujun9972 译者:译者ID 校对:校对者ID