sources/tech/20210101 Djinn- A Code Generator and Templating Language Inspired by Jinja2.md

10 KiB

Djinn: A Code Generator and Templating Language Inspired by Jinja2

Code generators can be useful tools. I sometimes use the command line version of Jinja2 to generate highly redundant config files and other text files, but it’s feature-limited for transforming data. Obviously the author of Jinja2 thinks differently, but I wanted something like list comprehensions or D’s composable range algorithms.

I decided to make a tool that’s like Jinja2, but lets me generate complex files by transforming data with range algorithms. The idea was dead simple: a templating language that gets rewritten directly to D code. That way it supports everything D does, simply because it is D. I wanted a standalone code generator, but thanks to D’s mixin feature, the same templating language works as an embedded templating language (for HTML in a web app, for example). (For more on that trick, see this post about translating Brainfuck to D to machine code all at compile time using mixins.)

As usual, it’s on GitLab. The examples in this post can be found there, too.

Hello world example

Here’s an example to demonstrate the idea:

Hello [= retro("dlrow") ]!

[: enum one = 1; :]

1 + 1 = [= one + one ]

[= some_expression ] is like {{ some_expression }} in Jinja2, and it renders a value to the output. [: some_statement; :] is like {% some_statement %} and causes full code statements to be executed. I changed the syntax because D also uses curly braces a lot, and mixing the two made templates hard to read. (There are also special non-D directives, like include, that get wrapped in [< and >].)

If you save the above to a file called hello.txt.dj and run the djinn command line tool against it, you’ll get a file called hello.txt containing what you might guess:

Hello world!

1 + 1 = 2

If you’ve used Jinja2, you might be wondering what happened to the second line. Djinn has a special rule that simplifies formatting and whitespace handling: if a source line contains [: statements or [< directives but doesn’t contain any non-whitespace output, the whole line is ignored for output purposes. Blank lines are still rendered.

Generating data

Okay, now for something a bit more practical: generating CSV data.

x,f(x)

[: import std.mathspecial;

foreach (x; iota(-1.0, 1.0, 0.1)) :]

[= "%0.1f,%g", x, normalDistribution(x) ]

A [= and ] pair can contain multiple expressions separated by commas. If the first expression is a double-quoted string, it’s interpreted as a format string. Here’s the output:

x,f(x)

-1.0,0.158655

-0.9,0.18406

-0.8,0.211855

-0.7,0.241964

-0.6,0.274253

-0.5,0.308538

-0.4,0.344578

-0.3,0.382089

-0.2,0.42074

-0.1,0.460172

0.0,0.5

0.1,0.539828

0.2,0.57926

0.3,0.617911

0.4,0.655422

0.5,0.691462

0.6,0.725747

0.7,0.758036

0.8,0.788145

0.9,0.81594

Making an image

This example is just for the heck of it. The classic netpbm image library defined a bunch of image formats, some of which are text-based. For example, here’s an image of a 3x3 cross:

P2 # identifier for Portable GrayMap

3 3 # width and height

7 # value for pure white (0 is black)

7 0 7

0 0 0

7 0 7

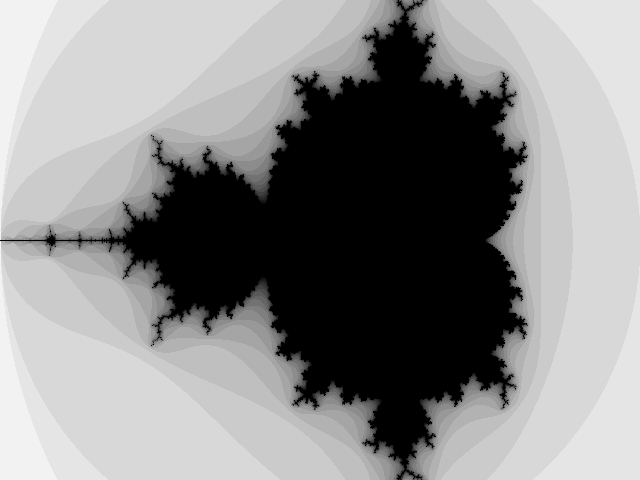

You can save the above text to a file named something like cross.pgm and many image tools will understand it. Here’s some Djinn code that generates a Mandelbrot set fractal in the same format:

[:

import std.complex;

enum W = 640;

enum H = 480;

enum kMaxIter = 20;

ubyte mb(uint x, uint y)

{

const c = complex(3.0 * (x - W / 1.5) / W, 2.0 * (y - H / 2.0) / H);

auto z = complex(0.0);

ubyte ret = kMaxIter;

while (abs(z) <= 2 && --ret) z = z * z + c;

return ret;

}

:]

P2

[= W ] [= H ]

[= kMaxIter ]

[: foreach (y; 0..H) :]

[= "%(%s %)", iota(W).map!(x => mb(x, y)) ]

The resulting file is about 800kB, but it compresses nicely as a PNG:

$ # Converting with GraphicsMagick

$ gm convert mandelbrot.pgm mandelbrot.png

And here it is:

Solving a puzzle

Here’s a puzzle:

The 5x5 grid needs to be filled in with numbers from 1 to 5, using each number once in each row, and once in each column. (I.e., to make a 5x5 Latin square.) The numbers in neighbouring cells must also satisfy the inequalities indicated by any > greater-than signs.

I used linear programming (LP) some months ago. LP problems are systems of continuous variables with linear constraints. This time I’ll use mixed integer linear programming (MILP), which generalises LP by also allowing integer-constrained variables. It turns out that’s enough to be NP complete, and MILP happens to be reasonably good for modelling this puzzle.

In that previous post, I used the Julia library JuMP to help spec the problem. This time I’ll use the CPLEX text-based format, which is supported by several LP and MILP solvers (and can be easily converted to other formats by off-the-shelf tools if needed). Here’s the LP from the previous post in CPLEX format:

Minimize

obj: v

Subject To

ptotal: pr + pp + ps = 1

rock: 4 ps - 5 pp - v <= 0

paper: 5 pr - 8 ps - v <= 0

scissors: 8 pp - 4 pr - v <= 0

Bounds

0 <= pr <= 1

0 <= pp <= 1

0 <= ps <= 1

End

CPLEX format is nice to read, but non-trivial problems take a lot of variables and constraints to model, making it painful and error-prone to write out manually. There are domain-specific languages like ZIMPL for speccing MILPs and LPs in a high-level way. They’re pretty cool for many problems, but ultimately they’re not as expressive as a general-purpose language with a good library like JuMP — or as a code generator with D.

I’ll model the puzzle using two sets of variables: (v_{r,c}) and (i_{r,c,v}). (v_{r,c}) will hold the value (1-5) of the cell at row (r) and column (c). (i_{r,c,v}) will be an indicator binary that’s 1 if the cell at row (r) and column (c) has value (v), and 0 otherwise. These two sets of variables are redundant representations of the grid, but the first representation makes it easier to model the inequality constraints, while the second representation makes it easier to model the uniqueness constraints. I just need to add some extra constraints to force the two representations to be consistent. But first, let’s start with the basic constraint that each cell must have exactly one value. Mathematically, that means all the indicators for a given row and column must be 0, except for one that is 1. That can be enforced by this equation:

[i_{r,c,1} + i_{r,c,2} + i_{r,c,3} + i_{r,c,4} + i_{r,c,5} = 1]

The CPLEX constraints for all rows and columns can be generated with this Djinn code:

\ Cell has one value

[:

foreach (r; iota(N))

foreach (c; iota(N))

:]

[= "%-(%s + %)", vs.map!(v => ivar(r, c, v)) ] = 1

[::]

ivar() is a helper function that gives us the string identifier for an (i) variable, and vs stores the numbers 1-5 for convenience. The constraints for uniqueness within rows and columns are exactly the same, but iterating over the other two dimensions of (i).

To make the (i) vars consistent with the (v) vars, we need constraints like this (remember, only one of the (i) vars is non-zero):

[i_{r,c,1} + 2i_{r,c,2} + 3i_{r,c,3} + 4i_{r,c,4} + 5i_{r,c,5} = v_{r,c}]

CPLEX requires all variables to be on the left, so the Djinn code looks like this:

\ Link i vars with v vars

[:

foreach (r; iota(N))

foreach (c; iota(N))

:]

[= "%-(%s + %)", vs.map!(v => text(v, ' ', ivar(r, c, v))) ] - [= vvar(r,c) ] = 0

[::]

The constraints for the neighouring cell inequalities and for the bottom left corner being 4 are all trivial to write. All that’s left is to declare the indicator variables to be binary, and set the bounds for the (v) vars. All up, there are 150 variables and 111 constraints, plus bounds for the variables. You can see the full code in the repo.

The GNU Linear Programming Kit has a command line tool that can solve this CPLEX MILP. Unfortunately, its output is a big dump of everything, so I used awk to pull out what’s needed:

$ time glpsol --lp inequality.lp -o /dev/stdout | awk '/v[0-9][0-9]/ { print $2, $4 }' | sort

v00 1

v01 3

v02 2

v03 5

v04 4

v10 2

v11 5

v12 4

v13 1

v14 3

v20 3

v21 1

v22 5

v23 4

v24 2

v30 5

v31 4

v32 3

v33 2

v34 1

v40 4

v41 2

v42 1

v43 3

v44 5

real 0m0.114s

user 0m0.106s

sys 0m0.005s

Here’s the solution written out in the original grid:

These examples are just for playing around, but I’m sure you get the idea. The README.md for the Djinn repo is itself generated using a Djinn template, by the way.

As I said, Djinn can also be used as a compile-time templating language embedded inside D code. I primarily wanted a code generator, but that’s a bonus thanks to D’s metaprogramming features.

via: https://theartofmachinery.com/2021/01/01/djinn.html

作者:Simon Arneaud 选题:lujun9972 译者:译者ID 校对:校对者ID