7.0 KiB

Building a sensing prosthetic with the Raspberry Pi

SenseBreast is an early prototype of a sensing mastectomy prosthetic

based on open hardware.

Content advisory: this article contains frank discussions of breast cancer.

What's the first question you ask your surgeon when you're discussing reconstruction options after breast cancer?

"How many USB ports can you give me?" is probably not the one that comes to mind for many people!

Although the remark was said jokingly, it sparked a thread that would ultimately become SenseBreast—an early prototype of a sensing mastectomy prosthetic, based on open hardware.

How did SenseBreast come about?

All technology has a history—an origin story of experimentation, missteps, successes, setbacks, and breakthroughs. SenseBreast is no different. SenseBreast was developed as a term project for the Masters of Applied Cybernetics—a highly selective course at the Australian National University's 3A Institute. The mission of the 3Ai is to bring artificial intelligence and cyber-physical systems safely, responsibly, and sustainably to scale. The purpose of the assignment was to explore the nexus between the electronic, virtual world, and the physical, tactile world.

What is SenseBreast?

SenseBreast combines two distinct elements: a cyber component—electronics, sensors, and storage for gathering data, and a physical component—a breast form designed to be worn inside a mastectomy bra. SenseBreast is a rudimentary cyber-physical system. In cyber-physical systems, physical and software components are deeply intertwined and interact in different ways depending on context.

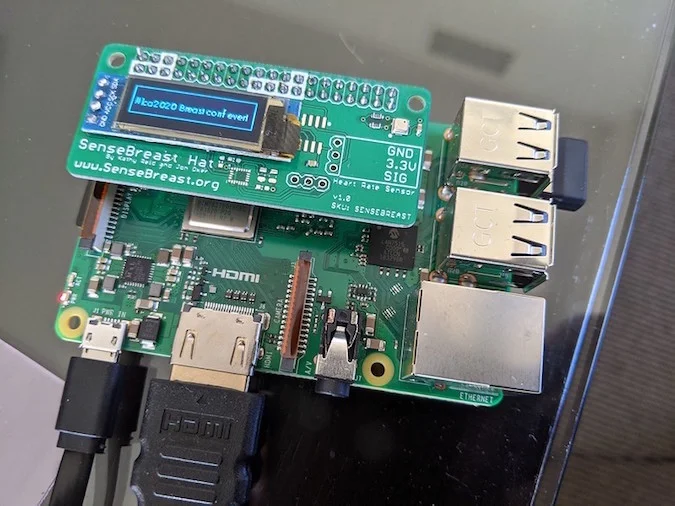

The SenseBreast draws on a rich heritage of open source hardware and software. Based on the Raspberry Pi 3B+, it uses the Debian-flavored Raspbian operating system, Python to interact with the onboard sensors, and d3.js to visualize the data that the sensors generate.

Early versions of the SenseBreast used the SenseHAT, but in the true spirit of open source collaboration, I partnered with Australian open source luminary Jon Oxer to develop a custom SenseBreast board. This contains an inertial motion unit (IMU) and temperature, humidity, and pressure sensors, just like the SenseHAT, but in addition, it contains the BME680 volatile gas sensor and a breakout for a heart rate monitor.

SenseBreast is wearable tech, so the physical form of the cyber-physical system is also important. Factors like comfort, texture, and fit in clothing are important in the design of wearables because technology isn't better unless it's better for people! The early attempts at building a housing for SenseBreast were spectacular failures; in fact, the very first iteration was put together using acrylic render and linen cloth, and held together with paper clips—in true hacker style! It wasn't comfortable to wear at all, but it served as a proof point for further exploration.

Later iterations used a different approach. This involved taking a cast of a breast, using quick-dry silicone supported by a plaster cast. The resulting mold was then used with slow-setting silicone to create a true-to-life shape. A recess was carved into the form to house the electronic components, and an additional silicone layer was added to protect the wearer's skin from contact with electronics.

What did we learn from SenseBreast?

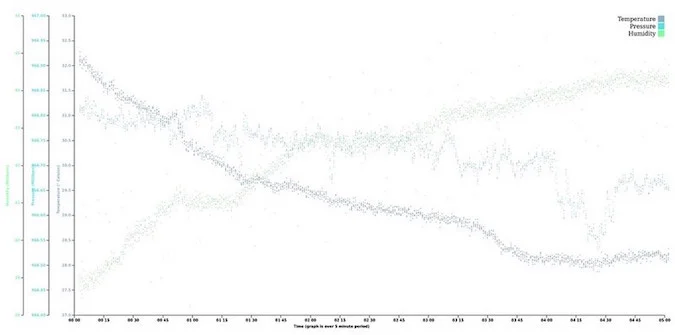

The key learning from SenseBreast is that data is partial. It only tells part of a story. It can be misleading and untrustworthy, which makes the decisions based on that data unreliable too. For example, the sensor data gathered by SenseBreast was affected by how hard the CPU was working. The graph below plots a sequence of 5 minutes of data from SenseBreast, just after the device has booted. You can see that the temperature decreases over time; this is because the CPU has to work harder as the Raspberry Pi boots, and then cools down after the boot operations are completed.

These sorts of learnings have implications on a broader scale.

What if the SenseBreast were not an open source device, but a commercial wearable that stored data about me? What if part of the business model of that company was to sell the data that was harvested? What if my health insurer had access to that data? Or prospective employers? Now, more than ever, it's important that we have private, open solutions for sensing data about ourselves.

What's next for the SenseBreast project?

The SenseBreast is a very early prototype, but it has the potential to develop through many different arcs. It could be used to assess range of movement post-surgery, to research how different garments and fabrics adjust to temperature and humidity, and to identify correlations between ambient air pressure and conditions such as lymphoedema. The path SenseBreast takes will be dependent on the passion, needs, and dedication of the incredible global open source community.

You can learn more about SenseBreast at https://sensebreast.org and see my presentation at linux.conf.au 2020 here.

The code for SenseBreast is available on GitHub.

Health IT has been surprisingly unwilling to deeply support open source software. Despite the huge...

via: https://opensource.com/article/20/4/raspberry-pi-sensebreast

作者:Kathy Reid 选题:lujun9972 译者:译者ID 校对:校对者ID