12 KiB

Why I rewrote my open source virtual reality server

With VRSpace, you can play group VR games across platforms without

sacrificing your privacy.

Look! I wrote a virtual reality (VR) server and published it on GitHub! But why?

Well, I'm your typical introverted hacker. I like to play with technology. Whenever something new comes out, I have to lay my hands on it and get them dirty. So, when I gifted myself Oculus Quest last year, I played a few games before I wanted to code something myself. And guess what? Everything is proprietary!

Alright, this may be a bit of an overstatement. But my overall impression of the VR industry is exactly that—it's all proprietary! Hardware and software vendors are trying to lock developers in to sell more devices and development tools than their competitors—deja vu, like the Unix wars in the last century.

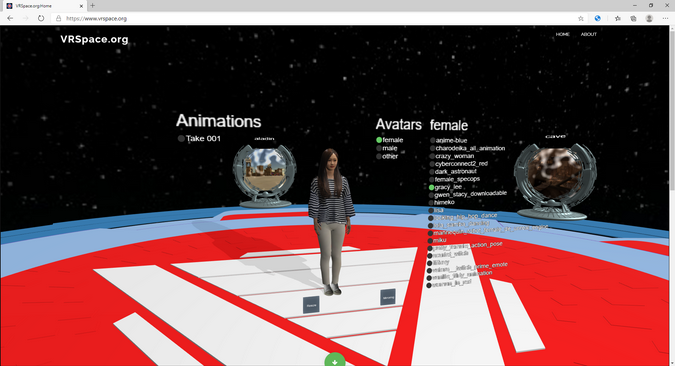

Choosing an avatar and portals to virtual spaces. (Gileon, hong227, Jasna Almasi, CC BY-SA 4.0)

But welcome to the 21st century; we live in clouds now! Clouds take all our data and store it somewhere safe at the cloud owner's mercy. Take Oculus Quest 2, for instance. You can't even use it without a Facebook account. But once you do, all your data goes to Facebook.

What kind of data? Biometric data.

VR devices track our movements, know our real-world height, and more. GDPR and other privacy laws include this type of biometric data in the highest security categories. Rightfully so, as this data enables the worst kind of privacy invasions. Imagine, for instance, a deepfake that mimics your every movement.

I'm using Facebook as an example, but the risks are the same with any private organization whose code cannot be scrutinized.

Building an open, interoperable VR server

Privacy is but one of my motivations for writing a VR server; the other is my family.

My kids play together in real life, and they also want to play together in VR. I have another VR headset, an Acer OJO, but that exists in a different world of Windows Mixed Reality from an Oculus. Once again, vendor lock-in gets in the way. For my kids to play VR together, we'd need two Microsoft or two Facebook headsets.

But there's a way out.

Enter the WebXR Device API. This open source specification "describes support for accessing virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) devices, including sensors and head-mounted displays, on the web." It's VR and AR (summarized by X) that works on every device, just as the web has to work on any device—including mobile devices.

WebXR includes a WebGL layer, and there are a number of JavaScript libraries (such as Three.js) to help developers working with WebGL and a full-featured open source game engine, BabylonJS. (Three.js fans might want to try CS1 Game Engine, a promising yet unfinished library with performance and developer experience as top priorities.)

The tools also interoperate with popular web development frameworks like Angular and React. There's also glTF, an open standard for 3D models that pretty much every relevant tool reads and writes, as well as an incredible number of open source 3D models that are mostly published under Creative Commons Attribution licenses.

The only thing missing was a server. One that would deliver content (models) and presentation logic (JavaScript), collect and distribute user events, and implement business (game) logic, but would not store any sensitive data.

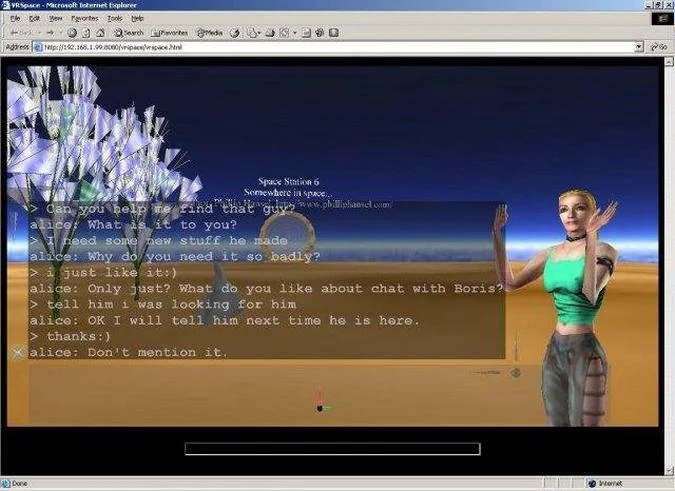

It just happens that 20 years ago, I wrote an open source VR server named VRSpace. Unfortunately, it was way too early for its own good, and the project died along with the client technology (VRML). But I knew exactly what I needed to do for today's VR, so I wrote it again. And luckily, it's much easier to do with modern technologies.

Twenty years ago, VRSpace.org was a chat with a chatbot. (Arni Barisic, Slaven Katic, Josip Almasi, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Rather than reflecting on the good ol' times and 20 years of technology gap, I'll talk about some of the design choices I made and the open source tools I used.

Two decades later: Java and JavaScript

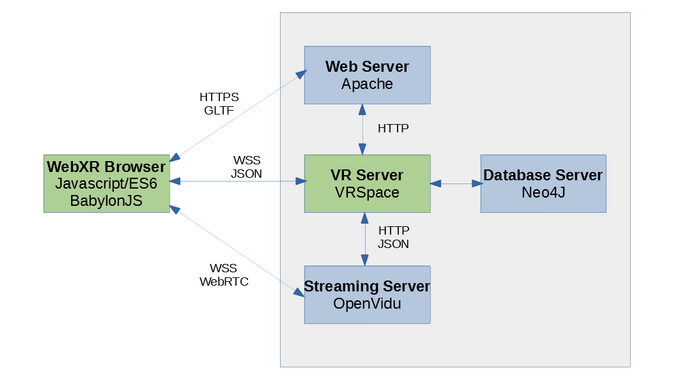

I chose Java and Spring Boot simply because I use them daily. But truth be told, Node.js might be a better tool for this job, as it is easier to develop and maintain software written in one language than two. For the client side, I chose BabylonJS, because it's a full-featured WebXR game engine and plain JavaScript, and I didn't want the client to depend on a user interface (UI) framework.

BabylonJS is written in TypeScript, so if I wanted to make a monolithic product, I'd go with TypeScript. On the other hand, I don't want to enforce any specific technology on the client side. Web browsers are not the only kind of client that will want to interact in VR, and native apps usually give the best performance.

The communication layer doesn't depend on anything else, which may be relevant if you want to implement your own VR client or a headless client like a chatbot.

To store the data, I chose the Neo4J database, which turned out to be as good as it gets. It can be embedded into my server and store all of my objects. Except for sensitive ones, of course, so I took special care to mark every sensitive field as transient. If I didn't care about this, you couldn't trust my server to protect your private data against nosy government institutions or criminals looking to steal valuable biometric data.

Communication happens with JSON over WebSockets—because it just works. Protocol-wise, it's far from the best choice. The sheer number of events emitted from VR device sensors is much higher than your usual first-person shooter; VR gear tracks your arms and head, various buttons and joysticks, possibly even eye movements, and every finger. Rate limiting is a must-have no matter what.

But what about chat? VR devices don't have keyboards, nor do mobile devices once they're head-mounted as VR gear. Virtual keyboards inside VR are not very useful, and they're certainly useless for chat. So voice chat seems the only option. Luckily, there's an open source chat server called OpenVidu. I made my server talk to that server so that people can chat with each other.

Last but not least, security. Embedding a script into a JSON string is trivial, and to prevent cross-site scripting attacks, the server must, at a minimum, sanitize each and every incoming request.

(Josip Almasi, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Wide-open virtual spaces

People need open spaces every once in a while, just to keep their sanity. Prisoners get at least an hour outside every day. NASA expects astronauts to be able to endure long periods of confinement. But ordinary people just can't stand being inside all the time.

I've been rather confined for months now, but VR to the rescue! Making a virtual space requires spending endless hours trying out different models and backgrounds and doing much more testing. For physical and mental health, it's not as good as the real stuff, but it's good enough to keep people sane.

VRSpace.org virtual worlds created by farhad.Guli, anthwolf, fenixman12, ShadowTan, Binkley-Spacetrucker, and exima113 (Josip Almasi, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Now that I've written the server, my kids can finally play hide and seek together in any virtual world they choose, with my wife and me alongside them—two VR headsets, a PC, and a mobile, all playing together. So far, we can only play hide and seek because there are not any other games yet. We started playing a "make a game" game; so far, we have a game map, the first level, and of course, zombies.

But what's the point of having software that nobody uses? My first VR server was not widely used, but it was used by people all over the world. I remember some students in Korea and a girl in Uruguay sitting on her daddy's lap, enchanted by dolphins flying through a virtual replica of a far-away city.

But my best memory is being told, "programmers like you are benefactors of humanity." This is what open source is all about: benefiting humanity. Not just me, not just my family, not just paying customers, not just my company, but anybody, anywhere and possibly everybody, everywhere.

And that is why I wrote that VR server again and published it on GitHub.

Get involved

I'm running a demo server of the current code, available to anyone anonymously. I installed a Redmine server on it; it has a wiki, forums, bug reports, and everything, so if you want to collaborate or just get in touch, see you there and on GitHub!

I also made a YouTube channel for demos and tutorials and made a few movies (with another open source tool called Shotcut). This video explains all of the project's features at a glance. And I made a Facebook page because literally everybody knows about Facebook.

I hope to see you in the virtual worlds, so stay safe and have fun!

Mozilla's MozVR is a new technology that combines the open web and virtual reality, enabling...

via: https://opensource.com/article/20/12/virtual-reality-server

作者:Josip Almasi 选题:lujun9972 译者:译者ID 校对:校对者ID