11 KiB

Here are all the Git commands I used last week, and what they do.

Image credit: GitHub Octodex

Image credit: GitHub Octodex

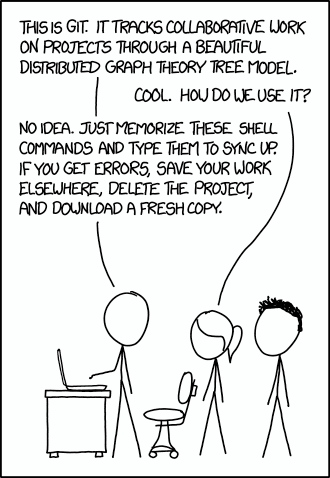

Like most newbies, I started out searching StackOverflow for Git commands, then copy-pasting answers, without really understanding what they did.

Image credit: XKCD

Image credit: XKCD

I remember thinking,“Wouldn’t it be nice if there were a list of the most common Git commands along with an explanation as to why they are useful?”

Well, here I am years later to compile such a list, and lay out some best practices that even intermediate-advanced developers should find useful.

To keep things practical, I’m basing this list off of the actual Git commands I used over the past week.

Almost every developer uses Git, and most likely GitHub. But the average developer probably only uses these three commands 99% of the time:

git add --all

git commit -am "<message>"

git push origin master

That’s all well and good when you’re working on a one-person team, a hackathon, or a throw-away app, but when stability and maintenance start to become a priority, cleaning up commits, sticking to a branching strategy, and writing coherent commit messages becomes important.

I’ll start with the list of commonly used commands to make it easier for newbies to understand what is possible with Git, then move into the more advanced functionality and best practices.

Regularly used commands

To initialize Git in a repository (repo), you just need to type the following command. If you don’t initialize Git, you cannot run any other Git commands within that repo.

git init

If you’re using GitHub and you’re pushing code to a GitHub repo that’s stored online, you’re using a remote repo. The default name (also known as an alias) for that remote repo is origin. If you’ve copied a project from Github, it already has an origin. You can view that origin with the command git remote -v, which will list the URL of the remote repo.

If you initialized your own Git repo and want to associate it with a GitHub repo, you’ll have to create one on GitHub, copy the URL provided, and use the command git remote add origin , with the URL provided by GitHub replacing “”. From there, you can add, commit, and push to your remote repo.

The last one is used when you need to change the remote repository. Let’s say you copied a repo from someone else and want to change the remote repository from the original owner’s to your own GitHub account. Follow the same process as git remote add origin, except use set-url instead to change the remote repo.

git remote -v

git remote add origin <url>

git remote set-url origin <url>

The most common way to copy a repo is to use git clone, followed by the URL of the repo.

Keep in mind that the remote repository will be linked to the account from which you cloned the repo. So if you cloned a repo that belongs to someone else, you will not be able to push to GitHub until you change the originusing the commands above.

git clone <url>

You’ll quickly find yourself using branches. If you don’t understand what branches are, there are other tutorials that are much more in-depth, and you should read those before proceeding (here’s one).

The command git branch lists all branches on your local machine. If you want to create a new branch, you can use git branch , with representing the name of the branch, such as “master”.

The git checkout command switches to an existing branch. You can also use the git checkout -b command to create a new branch and immediately switch to it. Most people use this instead of separate branch and checkout commands.

git branch

git branch <name>

git checkout <name>

git checkout -b <name>

If you’ve made a bunch of changes to a branch, let’s call it “develop”, and you want to merge that branch back into your master branch, you use the git merge command. You’ll want to checkout the master branch, then run git merge develop to merge develop into the master branch.

git merge <branch>

If you’re working with multiple people, you’ll find yourself in a position where a repo was updated on GitHub, but you don’t have the changes locally. If that’s the case, you can use git pull origin to pull the most recent changes from that remote branch.

git pull origin <branch>

If you’re curious to see what files have been changed and what’s being tracked, you can use git status. If you want to see how much each file has been changed, you can use git diff to see the number of lines changed in each file.

git status

git diff --stat

Advanced commands and best practices

Soon you reach a point where you want your commits to look nice and stay consistent. You might also have to fiddle around with your commit history to make your commits easier to comprehend or to revert an accidental breaking change.

The git log command lets you see the commit history. You’ll want to use this to see the history of your commits.

Your commits will come with messages and a hash, which is random series of numbers and letters. An example hash might look like this: c3d882aa1aa4e3d5f18b3890132670fbeac912f7

git log

Let’s say you pushed something that broke your app. Rather than fix it and push something new, you’d rather just go back one commit and try again.

If you want to go back in time and checkout your app from a previous commit, you can do this directly by using the hash as the branch name. This will detach your app from the current version (because you’re editing a historical record, rather than the current version).

git checkout c3d88eaa1aa4e4d5f

Then, if you make changes from that historical branch and you want to push again, you’d have to do a force push.

Caution: Force pushing is dangerous and should only be done if you absolutely must. It will overwrite the history of your app and you will lose whatever came after.

git push -f origin master

Other times it’s just not practical to keep everything in one commit. Perhaps you want to save your progress before trying something potentially risky, or perhaps you made a mistake and want to spare yourself the embarrassment of having an error in your version history. For that, we have git rebase.

Let’s say you have 4 commits in your local history (not pushed to GitHub) in which you’ve gone back and forth. Your commits look sloppy and indecisive. You can use rebase to combine all of those commits into a single, concise commit.

git rebase -i HEAD~4

The above command will open up your computer’s default editor (which is Vim unless you’ve set it to something else), with several options for how you can change your commits. It will look something like the code below:

pick 130deo9 oldest commit message

pick 4209fei second oldest commit message

pick 4390gne third oldest commit message

pick bmo0dne newest commit message

In order to combine these, we need to change the “pick” option to “fixup” (as the documentation below the code says) to meld the commits and discard the commit messages. Note that in vim, you need to press “a” or “i” to be able to edit the text, and to save and exit, you need to type the escapekey followed by “shift + z + z”. Don’t ask me why, it just is.

pick 130deo9 oldest commit message

fixup 4209fei second oldest commit message

fixup 4390gne third oldest commit message

fixup bmo0dne newest commit message

This will merge all of your commits into the commit with the message “oldest commit message”.

The next step is to rename your commit message. This is entirely a matter of opinion, but so long as you follow a consistent pattern, anything you do is fine. I recommend using the commit guidelines put out by Google for Angular.js.

In order to change the commit message, use the amend flag.

git commit --amend

This will also open vim, and the text editing and saving rules are the same as above. To give an example of a good commit message, here’s one following the rules from the guideline:

feat: add stripe checkout button to payments page

- add stripe checkout button

- write tests for checkout

One advantage to keeping with the types listed in the guideline is that it makes writing change logs easier. You can also include information in the footer (again, specified in the guideline) that references issues.

Note: you should avoid rebasing and squashing your commits if you are collaborating on a project, and have code pushed to GitHub. If you start changing version history under people’s noses, you could end up making everyone’s lives more difficult with bugs that are difficult to track.

There are an almost endless number of possible commands with Git, but these commands are probably the only ones you’ll need to know for your first few years of programming.

_Sam Corcos is the lead developer and co-founder of _ Sightline Maps _, the most intuitive platform for 3D printing topographical maps, as well as _ LearnPhoenix.io _, an intermediate-advanced tutorial site for building scalable production apps with Phoenix and React. Get $20 off of LearnPhoenix with the coupon code: _ free_code_camp

Show your support

Clapping shows how much you appreciated Sam Corcos’s story.

via: https://medium.freecodecamp.org/git-cheat-sheet-and-best-practices-c6ce5321f52

作者:Sam Corcos 译者:译者ID 校对:校对者ID