18 KiB

RHCSA Series: Reviewing Essential Commands & System Documentation – Part 1

RHCSA (Red Hat Certified System Administrator) is a certification exam from Red Hat company, which provides an open source operating system and software to the enterprise community, It also provides support, training and consulting services for the organizations.

RHCSA Exam Preparation Guide

RHCSA exam is the certification obtained from Red Hat Inc, after passing the exam (codename EX200). RHCSA exam is an upgrade to the RHCT (Red Hat Certified Technician) exam, and this upgrade is compulsory as the Red Hat Enterprise Linux was upgraded. The main variation between RHCT and RHCSA is that RHCT exam based on RHEL 5, whereas RHCSA certification is based on RHEL 6 and 7, the courseware of these two certifications are also vary to a certain level.

This Red Hat Certified System Administrator (RHCSA) is essential to perform the following core system administration tasks needed in Red Hat Enterprise Linux environments:

- Understand and use necessary tools for handling files, directories, command-environments line, and system-wide / packages documentation.

- Operate running systems, even in different run levels, identify and control processes, start and stop virtual machines.

- Set up local storage using partitions and logical volumes.

- Create and configure local and network file systems and its attributes (permissions, encryption, and ACLs).

- Setup, configure, and control systems, including installing, updating and removing software.

- Manage system users and groups, along with use of a centralized LDAP directory for authentication.

- Ensure system security, including basic firewall and SELinux configuration.

To view fees and register for an exam in your country, check the RHCSA Certification page.

To view fees and register for an exam in your country, check the RHCSA Certification page.

In this 15-article RHCSA series, titled Preparation for the RHCSA (Red Hat Certified System Administrator) exam, we will going to cover the following topics on the latest releases of Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7.

- Part 1: Reviewing Essential Commands & System Documentation

- Part 2: How to Perform File and Directory Management in RHEL 7

- Part 3: How to Manage Users and Groups in RHEL 7

- Part 4: Editing Text Files with Nano and Vim / Analyzing text with grep and regexps

- Part 5: Process Management in RHEL 7: boot, shutdown, and everything in between

- Part 6: Using ‘Parted’ and ‘SSM’ to Configure and Encrypt System Storage

- Part 7: Using ACLs (Access Control Lists) and Mounting Samba / NFS Shares

- Part 8: Securing SSH, Setting Hostname and Enabling Network Services

- Part 9: Installing, Configuring and Securing a Web and FTP Server

- Part 10: Yum Package Management, Automating Tasks with Cron and Monitoring System Logs

- Part 11: Firewall Essentials and Control Network Traffic Using FirewallD and Iptables

- Part 12: Automate RHEL 7 Installations Using ‘Kickstart’

- Part 13: RHEL 7: What is SELinux and how it works?

- Part 14: Use LDAP-based authentication in RHEL 7

- Part 15: Virtualization in RHEL 7: KVM and Virtual machine management

In this Part 1 of the RHCSA series, we will explain how to enter and execute commands with the correct syntax in a shell prompt or terminal, and explained how to find, inspect, and use system documentation.

RHCSA: Reviewing Essential Linux Commands – Part 1

Prerequisites:

At least a slight degree of familiarity with basic Linux commands such as:

- cd command (change directory)

- ls command (list directory)

- cp command (copy files)

- mv command (move or rename files)

- touch command (create empty files or update the timestamp of existing ones)

- rm command (delete files)

- mkdir command (make directory)

The correct usage of some of them are anyway exemplified in this article, and you can find further information about each of them using the suggested methods in this article.

Though not strictly required to start, as we will be discussing general commands and methods for information search in a Linux system, you should try to install RHEL 7 as explained in the following article. It will make things easier down the road.

Interacting with the Linux Shell

If we log into a Linux box using a text-mode login screen, chances are we will be dropped directly into our default shell. On the other hand, if we login using a graphical user interface (GUI), we will have to open a shell manually by starting a terminal. Either way, we will be presented with the user prompt and we can start typing and executing commands (a command is executed by pressing the Enter key after we have typed it).

Commands are composed of two parts:

- the name of the command itself, and

- arguments

Certain arguments, called options (usually preceded by a hyphen), alter the behavior of the command in a particular way while other arguments specify the objects upon which the command operates.

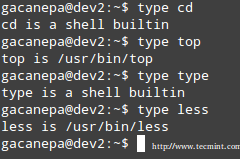

The type command can help us identify whether another certain command is built into the shell or if it is provided by a separate package. The need to make this distinction lies in the place where we will find more information about the command. For shell built-ins we need to look in the shell’s man page, whereas for other binaries we can refer to its own man page.

Check Shell built in Commands

In the examples above, cd and type are shell built-ins, while top and less are binaries external to the shell itself (in this case, the location of the command executable is returned by type).

Other well-known shell built-ins include:

- echo command: Displays strings of text.

- pwd command: Prints the current working directory.

More Built in Shell Commands

exec command

Runs an external program that we specify. Note that in most cases, this is better accomplished by just typing the name of the program we want to run, but the exec command has one special feature: rather than create a new process that runs alongside the shell, the new process replaces the shell, as can verified by subsequent.

# ps -ef | grep [original PID of the shell process]

When the new process terminates, the shell terminates with it. Run exec top and then hit the q key to quit top. You will notice that the shell session ends when you do, as shown in the following screencast:

注:youtube视频

export command

Exports variables to the environment of subsequently executed commands.

history Command

Displays the command history list with line numbers. A command in the history list can be repeated by typing the command number preceded by an exclamation sign. If we need to edit a command in history list before executing it, we can press Ctrl + r and start typing the first letters associated with the command. When we see the command completed automatically, we can edit it as per our current need:

注:youtube视频

This list of commands is kept in our home directory in a file called .bash_history. The history facility is a useful resource for reducing the amount of typing, especially when combined with command line editing. By default, bash stores the last 500 commands you have entered, but this limit can be extended by using the HISTSIZE environment variable:

Linux history Command

But this change as performed above, will not be persistent on our next boot. In order to preserve the change in the HISTSIZE variable, we need to edit the .bashrc file by hand:

# for setting history length see HISTSIZE and HISTFILESIZE in bash(1)

HISTSIZE=1000

Important: Keep in mind that these changes will not take effect until we restart our shell session.

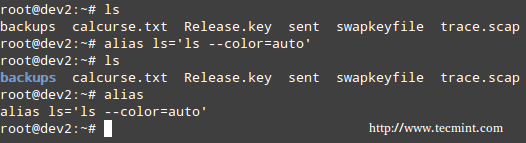

alias command

With no arguments or with the -p option prints the list of aliases in the form alias name=value on standard output. When arguments are provided, an alias is defined for each name whose value is given.

With alias, we can make up our own commands or modify existing ones by including desired options. For example, suppose we want to alias ls to ls –color=auto so that the output will display regular files, directories, symlinks, and so on, in different colors:

# alias ls='ls --color=auto'

Linux alias Command

Note: That you can assign any name to your “new command” and enclose as many commands as desired between single quotes, but in that case you need to separate them by semicolons, as follows:

# alias myNewCommand='cd /usr/bin; ls; cd; clear'

exit command

The exit and logout commands both terminate the shell. The exit command terminates any shell, but the logout command terminates only login shells—that is, those that are launched automatically when you initiate a text-mode login.

If we are ever in doubt as to what a program does, we can refer to its man page, which can be invoked using the man command. In addition, there are also man pages for important files (inittab, fstab, hosts, to name a few), library functions, shells, devices, and other features.

Examples:

- man uname (print system information, such as kernel name, processor, operating system type, architecture, and so on).

- man inittab (init daemon configuration).

Another important source of information is provided by the info command, which is used to read info documents. These documents often provide more information than the man page. It is invoked by using the info keyword followed by a command name, such as:

# info ls

# info cut

In addition, the /usr/share/doc directory contains several subdirectories where further documentation can be found. They either contain plain-text files or other friendly formats.

Make sure you make it a habit to use these three methods to look up information for commands. Pay special and careful attention to the syntax of each of them, which is explained in detail in the documentation.

Converting Tabs into Spaces with expand Command

Sometimes text files contain tabs but programs that need to process the files don’t cope well with tabs. Or maybe we just want to convert tabs into spaces. That’s where the expand tool (provided by the GNU coreutils package) comes in handy.

For example, given the file NumbersList.txt, let’s run expand against it, changing tabs to one space, and display on standard output.

# expand --tabs=1 NumbersList.txt

Linux expand Command

The unexpand command performs the reverse operation (converts spaces into tabs).

Display the first lines of a file with head and the last lines with tail

By default, the head command followed by a filename, will display the first 10 lines of the said file. This behavior can be changed using the -n option and specifying a certain number of lines.

# head -n3 /etc/passwd

# tail -n3 /etc/passwd

Linux head and tail Command

One of the most interesting features of tail is the possibility of displaying data (last lines) as the input file grows (tail -f my.log, where my.log is the file under observation). This is particularly useful when monitoring a log to which data is being continually added.

Read More: Manage Files Effectively using head and tail Commands

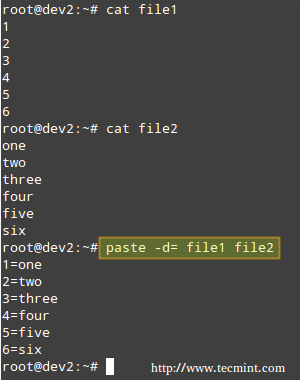

Merging Lines with paste

The paste command merges files line by line, separating the lines from each file with tabs (by default), or another delimiter that can be specified (in the following example the fields in the output are separated by an equal sign).

# paste -d= file1 file2

Merge Files in Linux

Breaking a file into pieces using split command

The split command is used split a file into two (or more) separate files, which are named according to a prefix of our choosing. The splitting can be defined by size, chunks, or number of lines, and the resulting files can have a numeric or alphabetic suffixes. In the following example, we will split bash.pdf into files of size 50 KB (-b 50KB), using numeric suffixes (-d):

# split -b 50KB -d bash.pdf bash_

Split Files in Linux

You can merge the files to recreate the original file with the following command:

# cat bash_00 bash_01 bash_02 bash_03 bash_04 bash_05 > bash.pdf

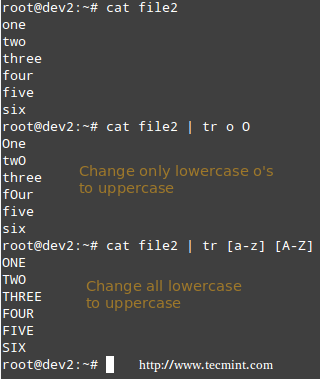

Translating characters with tr command

The tr command can be used to translate (change) characters on a one-by-one basis or using character ranges. In the following example we will use the same file2 as previously, and we will change:

-

lowercase o’s to uppercase,

-

and all lowercase to uppercase

cat file2 | tr o O

cat file2 | tr [a-z] [A-Z]

Translate Characters in Linux

Reporting or deleting duplicate lines with uniq and sort command

The uniq command allows us to report or remove duplicate lines in a file, writing to stdout by default. We must note that uniq does not detect repeated lines unless they are adjacent. Thus, uniq is commonly used along with a preceding sort (which is used to sort lines of text files).

By default, sort takes the first field (separated by spaces) as key field. To specify a different key field, we need to use the -k option. Please note how the output returned by sort and uniq change as we change the key field in the following example:

# cat file3

# sort file3 | uniq

# sort -k2 file3 | uniq

# sort -k3 file3 | uniq

Remove Duplicate Lines in Linux

Extracting text with cut command

The cut command extracts portions of input lines (from stdin or files) and displays the result on standard output, based on number of bytes (-b), characters (-c), or fields (-f).

When using cut based on fields, the default field separator is a tab, but a different separator can be specified by using the -d option.

# cut -d: -f1,3 /etc/passwd # Extract specific fields: 1 and 3 in this case

# cut -d: -f2-4 /etc/passwd # Extract range of fields: 2 through 4 in this example

Extract Text From a File in Linux

Note that the output of the two examples above was truncated for brevity.

Reformatting files with fmt command

fmt is used to “clean up” files with a great amount of content or lines, or with varying degrees of indentation. The new paragraph formatting defaults to no more than 75 characters wide. You can change this with the -w (width) option, which set the line length to the specified number of characters.

For example, let’s see what happens when we use fmt to display the /etc/passwd file setting the width of each line to 100 characters. Once again, output has been truncated for brevity.

# fmt -w100 /etc/passwd

File Reformatting in Linux

Formatting content for printing with pr command

pr paginates and displays in columns one or more files for printing. In other words, pr formats a file to make it look better when printed. For example, the following command:

# ls -a /etc | pr -n --columns=3 -h "Files in /etc"

Shows a listing of all the files found in /etc in a printer-friendly format (3 columns) with a custom header (indicated by the -h option), and numbered lines (-n).

File Formatting in Linux

Summary

In this article we have discussed how to enter and execute commands with the correct syntax in a shell prompt or terminal, and explained how to find, inspect, and use system documentation. As simple as it seems, it’s a large first step in your way to becoming a RHCSA.

If you would like to add other commands that you use on a periodic basis and that have proven useful to fulfill your daily responsibilities, feel free to share them with the world by using the comment form below. Questions are also welcome. We look forward to hearing from you!

via: http://www.tecmint.com/rhcsa-exam-reviewing-essential-commands-system-documentation/

作者:Gabriel Cánepa 译者:译者ID 校对:校对者ID