mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-01-04 22:00:34 +08:00

195 lines

19 KiB

Markdown

195 lines

19 KiB

Markdown

Yes, Python is Slow, and I Don’t Care

|

||

============================================================

|

||

|

||

### A rant on sacrificing performance for productivity.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

I’m taking a break from my discussion on asyncio in Python to talk about something that has been on my mind recently: the speed of Python. For those who don’t know, I am somewhat of a Python fanboy, and I aggressively use Python everywhere I can. One of the biggest complaints people have against Python is that it’s slow. Some people almost refuse to even try python because its slower than X. Here are my thoughts as to why you should try python, despite it being slow.

|

||

|

||

### Speed No Longer Matters

|

||

|

||

It used to be the case that programs took a really long time to run. CPU’s were expensive, memory was expensive. Running time of a program used to be an important metric. Computers were very expensive, and so was the electricity to run them. Optimization of these resources was done because of an eternal business law:

|

||

|

||

> Optimize your most expensive resource.

|

||

|

||

Historically, the most expensive resource was computer run time. This is what lead to the study of computer science which focuses on efficiency of different algorithms. However, this is no longer true, as silicon is now cheap. Like really cheap. Run time is no longer your most expensive resource. A company’s most expensive resource is now its employee’s time. Or in other words, you. It’s more important to get stuff done than to make it go fast. In fact this is so important, I am going to put it again right here as if it was a quote (for those who are just browsing):

|

||

|

||

> It’s more important to get stuff done than to make it go fast.

|

||

|

||

You might be saying, “My company cares about speed, I build a web application and all responses have to be faster than x milliseconds.” Or, “We have had customers cancel because they think our app is too slow.” I am not trying to say that speed doesn’t matter at all, I am simply trying to say that its no longer the most important thing; it’s not your most expensive resource.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

### Speed Is The Only Thing That Matters

|

||

|

||

When you say _speed_ in the context of programming, you typically mean performance, aka CPU cycles. When your CEO say’s _speed_ in the context of programming he means business speed. The most important metric is time-to-market. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter how fast your product/web app is. It doesn’t matter what language its written in. It doesn't even matter how much money it takes to run. At the end of the day, the one thing that will make your company survive or die is time-to-market. I’m not just talking about the startup idea of how long it takes till you make money, but more so the time frame of “from idea, to customers hands.” The only way to survive in business is to innovate faster than your competitors. It doesn’t matter how many good ideas you come up with if your competitors “ship” before you do. You have to be the first to market, or at least keep up. Once you slow down, you are done.

|

||

|

||

> The only way to survive in business is to innovate faster than your competitors.

|

||

|

||

#### A Case of Microservices

|

||

|

||

Companies like Amazon, Google, and Netflix understand the importance of moving fast. They have created a business system where they can move fast and innovate quickly. Microservices are the solution to their problem. This article has nothing to do with whether or not you should be using microservices, but at least accept that Amazon and Google think they should be using them.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Microservices are inherently slow. The very concept of a microservice is to break up a boundary by a network call. This means you are taking what was a function call (a couple cpu cycles) and turning it into a network call. There isn’t much you could do that is worse in terms of performance. Network calls are really slow compared to the CPU. But these big companies still choose to use microservices. There really isn’t an architecture slower than microservices that I know of. Microservices’ biggest con is performance, but greatest pro is time-to-market. By building teams around smaller projects and code bases, a company is able to iterate and innovate at a much faster pace. This just goes to show that very large companies also care about time-to-market, not just startups.

|

||

|

||

#### CPU is Not your Bottleneck

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

If you write a network application, such as a web server, chances are, CPU time is not the bottleneck of your application. When your web server handles a request, it probably makes a couple network calls, such as to your database, or perhaps a cache server like Redis. While these services themselves may be fast, the network call to them is slow. [There is a really great blog article on the speed differences of certain operations.][1] In the article, the author scales CPU cycle times into more understandable human times. If a single CPU cycle was the equivalent of 1 second, then a network call from California to New York, would be the equivalent of 4 years. That is how much slower network is. For some rough estimates, let’s say a normal network call inside the same data center takes about 3 ms. That would be the equivalent of 3 months in our “human scale”. Now imagine your program is very CPU intensive, it takes 100,000 cycles to respond to a single call. That would be the equivalent of just over 1 day. Now let’s say you use a language that is 5 times as slow, now it takes about 5 days. Well, compare that to our 3 month network call, and the 4 day difference doesn’t really matter much at all. If someone has to wait at least 3 months for a package, I don't think an extra 4 days will really matter all that much to them.

|

||

|

||

What this ultimately means is that, even if python is slow, it doesn’t matter. The speed of the language (or CPU time) is almost never the issue. Google actually did a study on this very concept, and [they wrote a paper on it][2]. The paper talks about designing a high throughput system. In the conclusion, they say:

|

||

|

||

> It may seem paradoxical to use an interpreted language in a high-throughput environment, but we have found that the CPU time is rarely the limiting factor; the expressibility of the language means that most programs are small and spend most of their time in I/O and native run-time code. Moreover, the flexibility of an interpreted implementation has been helpful, both in ease of experimentation at the linguistic level and in allowing us to explore ways to distribute the calculation across many machines.

|

||

|

||

or, to emphasise:

|

||

|

||

> the CPU time is rarely the limiting factor

|

||

|

||

#### What if CPU time is an issue?

|

||

|

||

You might be saying, “That’s great and all, but we have had issues where CPU was our bottleneck and caused much slowdown for our web app”, or “Language _x _ requires much less hardware to run than language _y_ on the server.” This all might be true. The wonderful thing about web servers is that you can load balance them almost infinitely. In other words, throw more hardware at it. Sure, Python might require better hardware than other languages, such as C. Just throw hardware at your CPU problem. Hardware is very cheap compared to your time. If you save a couple weeks worth of time in productivity in a year, that will more than pay for the added hardware cost.

|

||

|

||

|

||

* * *

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

### So, is Python faster?

|

||

|

||

This whole time I have been talking about how the most important thing is development time. So the question remains: Is Python faster than language X when it comes to development time? Anecdotally, I, [google][3], [and][4] [several][5][others][6], can tell you how much more [productive][7] Python is. It abstracts so many things for you, helping you focus on what you’re really trying to code, without getting stuck in the weeds of the small things such as whether you should use a vector or an array. But you might not like to take others’ word for it, so let’s look at some more empirical data.

|

||

|

||

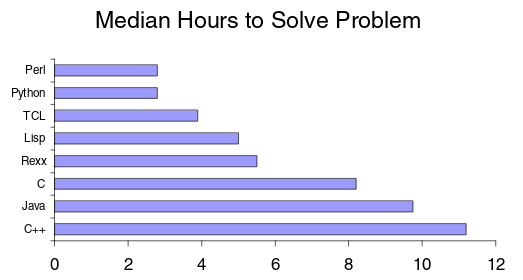

For the most part, this debate on whether python is more productive or not really comes down to scripting (or dynamic languages) vs statically typed languages. I think it is commonly excepted that statically typed languages are less productive, but [here is a good paper][8] that explains why. In terms of Python specifically, [here is a good summary][9] from a study that looked at how long it took to write code for strings processing in various languages.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

How long it takes to write a string processing application in various languages. (Prechelt and Garret)

|

||

|

||

Python is more than 2x as productive as Java in the above study. There are some other studies that show the same thing as well. Rosetta Code did a [fairly in-depth study][10] of the difference of programming languages. In the paper, they compare python to other scripting/interpreted languages and say:

|

||

|

||

> Python tends to be the most concise, even against functional languages (1.2–1.6 times shorter on average)

|

||

|

||

The common trend seems to be that “lines of code” is always less in Python. Lines of code might sound like a terrible metric, but [multiple studies][11], including the two already mentioned show that time spent per line of code is about the same in every language. Therefore, limiting the number of lines of code, increases productivity. Even the codinghorror himself (a C# programmer) [wrote an article on how Python is more productive][12].

|

||

|

||

I think it is fair to say that Python is more productive than many other languages. This is mainly due to the fact that python comes with “batteries included” and has many 3rd party libraries. [Here is a simple article talking about the differences between Python and X.][13] If you don’t know why Python is so “small” and productive, I invite you to take this opportunity to learn some python and see for yourself. Here is your first program:

|

||

|

||

_import __hello___

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

* * *

|

||

|

||

### But what if speed really does matter?

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

The tone of the points above might make it sound like optimization and speed don't matter at all. But the truth is, there are many times when runtime performance really does matter. One example is, you have a web application, and there is a specific endpoint that is taking a really long time to respond. You know how fast it needs to be, and how much it needs to be improved.

|

||

|

||

In our example, a couple things happened:

|

||

|

||

1. We noticed a single endpoint that was performing slowly

|

||

2. We recognize it as slow because we have a metric of what is considered _fast enough_ , and it’s failing that metric.

|

||

|

||

We don’t have to micro-optimize everything in an application. Everything only needs to be “fast enough”. Your users might notice if an endpoint takes a couple seconds to respond, but they won’t notice you improved the response time of a 35 ms call to 25 ms. “Good enough”, really is all you need to achieve. _Disclaimer_ : _I should probably state that there are _ _some _ _applications, such as real-time bidding applications, that _ _do _ _need micro optimizations, and every millisecond does matter. But that is the exception, not the rule._

|

||

|

||

In order to figure out how to optimize the endpoint your first step would be to profile the code and try to figure out where you bottleneck is. After all:

|

||

|

||

> Any improvements made anywhere besides the bottleneck are an illusion. — Gene Kim

|

||

|

||

If your optimizations aren’t touching the bottleneck, you’re wasting your time and not fixing the real issue. You wont get any serious improvements until you optimize the bottleneck. If you try to optimize before you know what the bottleneck is, you’ll just end up playing whack-a-mole with parts of your code. Optimizing code before you measure and determine where the bottleneck is, is known as “premature optimization”. Donald Knuth is often attributed for the following quote, but he claims he stole the quote from someone else:

|

||

|

||

> _Premature optimization is the root of all evil._

|

||

|

||

In talking about maintaining code bases, the more full quote from Donald Knuth is:

|

||

|

||

> We should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of the time: premature optimization is the root of all evil. Yet we should not pass up our opportunities in that critical 3%.

|

||

|

||

In other words, he is saying that most of the time, you need to forget about optimizing your code. Its almost always good enough. In the cases when it isn’t good enough, we typically only need to touch three percent of the code path. You don’t win any prizes by making your endpoint a couple nanoseconds faster because you used an if statement instead of a function for example. Optimize only after you measure.

|

||

|

||

Premature optimization includes calling certain _faster_ methods, or even using a specific data structure because it’s generally faster. Computer Science argues that if a method or algorithm has the same asymptotic growth (or Big-O) as another, then they are equivalent, even if one is 2x as slow in practice. Computers are so fast, that the computational growth of an algorithm as data/usage increases matters much more than the actual speed itself. In other words, if you have two _O(log n)_ functions, but one is twice as slow, it doesn’t really matter. As the size of data increases, they both “slow down” at the same rate. This is why premature optimization is the root of all evil; It wastes our time, and almost never actually helps our general performance anyways.

|

||

|

||

In terms of Big-O, you could argue that all languages are _O(n) _ for your program where n is lines of code, or instructions. They all grow at the same rate for the same instructions. It doesn’t matter how slow a language/runtime is, in terms of asymptotic growth, all languages are created equal. Under this logic, you could say that choosing a language for your application simply because its “fast” is the ultimate form of premature optimization. Your choosing something supposedly fast without measuring, without understanding where the bottleneck is going to be.

|

||

|

||

> Choosing a language for you application simply because its “fast” is the ultimate form of premature optimization.

|

||

|

||

|

||

* * *

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

### Optimizing Python

|

||

|

||

One of my favorite things about Python is that it lets you optimize code a little bit at a time. Lets say you have a method in Python that you find to be your bottleneck. You have optimized it several times, possibly following some guidance from [here][14] and [there][15], and now you are at the point where you are pretty sure Python itself is the bottleneck. Python has the ability to call into C code, which means that you can rewrite this one method in C to reduce the performance issue. You can do this one method at a time. This process allows you to write well optimized bottleneck methods in any language that compiles to C compatible assembler. This allows you to stay in Python most of the time, and only go into the lower level things when you really need it.

|

||

|

||

There is a language called Cython that is a super-set of Python. It is almost a merge of Python and C, and is a progressively typed language. Any Python code is valid Cython code, and Cython compiles to C code. With Cython, you can write a module or method, and slowly progress to more and more C-Types and performance. You can intermingle C types and Python’s duck types together. Using Cython you get the perfect mix of optimizing only at the bottleneck, and the beauty of Python everywhere else.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

A screenshot of Eve online: A space MMO written in Python

|

||

|

||

When you do eventually run into a Python wall of performance woes, you don't need to move your whole code base to a different language. You can almost always get the performance you need by just re-writing a couple methods in Cython. This is the strategy [Eve Online][16] takes. Eve is a Massive Multiplayer Computer Game, that uses Python and Cython for the entire stack. They achieve game level performance by optimizing the bottlenecks in C/Cython. If it works for them, it should work for most anyone. Alternatively, there are also other ways to optimize your python. For example, [PyPy][17] is a JIT implementation of Python that could give you significant runtime improvements for long running applications (such as a web server) simply by swapping out CPython (the default implementation) with PyPy.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

Lets review some of the main points:

|

||

|

||

* Optimize for your most expensive resource. That’s YOU, not the computer.

|

||

* Choose a language/framework/architecture that helps you develop quickly (such as Python). Do not choose technologies simply because they are fast.

|

||

* When you do have performance issues: find your bottleneck

|

||

* Your bottleneck is most likely not CPU or Python itself.

|

||

* If Python is your bottleneck (you’ve already optimized algorithms/etc.), then move the hot-spot to Cython/C

|

||

* Go back to enjoying getting things done quickly

|

||

|

||

|

||

* * *

|

||

|

||

I hope you enjoyed reading this article as much as I enjoyed writing it. If you’d like to say thank you, just hit the heart button. Also, if you’d like to talk to me about Python sometime, you can hit me up on twitter (@nhumrich) or I can be found on the [Python slack channel][18].

|

||

|

||

|

||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||

|

||

作者简介:

|

||

|

||

I drink the KoolAid of Continuous Delivery and write tools to help us all get there. Python hacker, Technology fanatic. Currently a devops engineer @canopytax

|

||

|

||

--------------

|

||

|

||

via: https://hackernoon.com/yes-python-is-slow-and-i-dont-care-13763980b5a1

|

||

|

||

作者:[Nick Humrich ][a]

|

||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||

|

||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||

|

||

[a]:https://hackernoon.com/@nhumrich

|

||

[1]:https://blog.codinghorror.com/the-infinite-space-between-words/

|

||

[2]:https://static.googleusercontent.com/media/research.google.com/en//archive/sawzall-sciprog.pdf

|

||

[3]:https://www.codefellows.org/blog/5-reasons-why-python-is-powerful-enough-for-google/

|

||

[4]:https://www.lynda.com/Python-tutorials/Python-Programming-Efficiently/534425-2.html

|

||

[5]:https://www.linuxjournal.com/article/3882

|

||

[6]:https://www.codeschool.com/blog/2016/01/27/why-python/

|

||

[7]:http://pythoncard.sourceforge.net/what_is_python.html

|

||

[8]:http://www.tcl.tk/doc/scripting.html

|

||

[9]:http://www.connellybarnes.com/documents/language_productivity.pdf

|

||

[10]:https://arxiv.org/pdf/1409.0252.pdf

|

||

[11]:http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.113.1831&rep=rep1&type=pdf

|

||

[12]:https://blog.codinghorror.com/are-all-programming-languages-the-same/

|

||

[13]:https://www.python.org/doc/essays/comparisons/

|

||

[14]:https://wiki.python.org/moin/PythonSpeed

|

||

[15]:https://wiki.python.org/moin/PythonSpeed/PerformanceTips

|

||

[16]:https://www.eveonline.com/

|

||

[17]:http://pypy.org/

|

||

[18]:http://pythondevelopers.herokuapp.com/

|