mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-01-04 22:00:34 +08:00

323 lines

18 KiB

Markdown

323 lines

18 KiB

Markdown

BriFuture is translating

|

||

|

||

|

||

Testing Node.js in 2018

|

||

============================================================

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

[Stream][4] powers feeds for over 300+ million end users. With all of those users relying on our infrastructure, we’re very good about testing everything that gets pushed into production. Our primary codebase is written in Go, with some remaining bits of Python.

|

||

|

||

Our recent showcase application, [Winds 2.0][5], is built with Node.js and we quickly learned that our usual testing methods in Go and Python didn’t quite fit. Furthermore, creating a proper test suite requires a bit of upfront work in Node.js as the frameworks we are using don’t offer any type of built-in test functionality.

|

||

|

||

Setting up a good test framework can be tricky regardless of what language you’re using. In this post, we’ll uncover the hard parts of testing with Node.js, the various tooling we decided to utilize in Winds 2.0, and point you in the right direction for when it comes time for you to write your next set of tests.

|

||

|

||

### Why Testing is so Important

|

||

|

||

We’ve all pushed a bad commit to production and faced the consequences. It’s not a fun thing to have happen. Writing a solid test suite is not only a good sanity check, but it allows you to completely refactor code and feel confident that your codebase is still functional. This is especially important if you’ve just launched.

|

||

|

||

If you’re working with a team, it’s extremely important that you have test coverage. Without it, it’s nearly impossible for other developers on the team to know if their contributions will result in a breaking change (ouch).

|

||

|

||

Writing tests also encourage you and your teammates to split up code into smaller pieces. This makes it much easier to understand your code, and fix bugs along the way. The productivity gains are even bigger, due to the fact that you catch bugs early on.

|

||

|

||

Finally, without tests, your codebase might as well be a house of cards. There is simply zero certainty that your code is stable.

|

||

|

||

### The Hard Parts

|

||

|

||

In my opinion, most of the testing problems we ran into with Winds were specific to Node.js. The ecosystem is always growing. For example, if you are on macOS and run “brew upgrade” (with homebrew installed), your chances of seeing a new version of Node.js are quite high. With Node.js moving quickly and libraries following close behind, keeping up to date with the latest libraries is difficult.

|

||

|

||

Below are a few pain points that immediately come to mind:

|

||

|

||

1. Testing in Node.js is very opinionated and un-opinionated at the same time. Many people have different views on how a test infrastructure should be built and measured for success. The sad part is that there is no golden standard (yet) for how you should approach testing.

|

||

|

||

2. There are a large number of frameworks available to use in your application. However, they are generally minimal with no well-defined configuration or boot process. This leads to side effects that are very common, and yet hard to diagnose; so, you’ll likely end up writing your own test runner from scratch.

|

||

|

||

3. It’s almost guaranteed that you will be _required_ to write your own test runner (we’ll get to this in a minute).

|

||

|

||

The situations listed above are not ideal and it’s something that the Node.js community needs to address sooner rather than later. If other languages have figured it out, I think it’s time for Node.js, a widely adopted language, to figure it out as well.

|

||

|

||

### Writing Your Own Test Runner

|

||

|

||

So… you’re probably wondering what a test runner _is_ . To be honest, it’s not that complicated. A test runner is the highest component in the test suite. It allows for you to specify global configurations and environments, as well as import fixtures. One would assume this would be simple and easy to do… Right? Not so fast…

|

||

|

||

What we learned is that, although there is a solid number of test frameworks out there, not a single one for Node.js provides a unified way to construct your test runner. Sadly, it’s up to the developer to do so. Here’s a quick breakdown of the requirements for a test runner:

|

||

|

||

* Ability to load different configurations (e.g. local, test, development) and ensure that you _NEVER_ load a production configuration — you can guess what goes wrong when that happens.

|

||

|

||

* Lift and seed a database with dummy data for testing. This must work for various databases, whether it be MySQL, PostgreSQL, MongoDB, or any other, for that matter.

|

||

|

||

* Ability to load fixtures (files with seed data for testing in a development environment).

|

||

|

||

With Winds, we chose to use Mocha as our test runner. Mocha provides an easy and programmatic way to run tests on an ES6 codebase via command-line tools (integrated with Babel).

|

||

|

||

To kick off the tests, we register the Babel module loader ourselves. This provides us with finer grain greater control over which modules are imported before Babel overrides Node.js module loading process, giving us the opportunity to mock modules before any tests are run.

|

||

|

||

Additionally, we also use Mocha’s test runner feature to pre-assign HTTP handlers to specific requests. We do this because the normal initialization code is not run during tests (server interactions are mocked by the Chai HTTP plugin) and run some safety check to ensure we are not connecting to production databases.

|

||

|

||

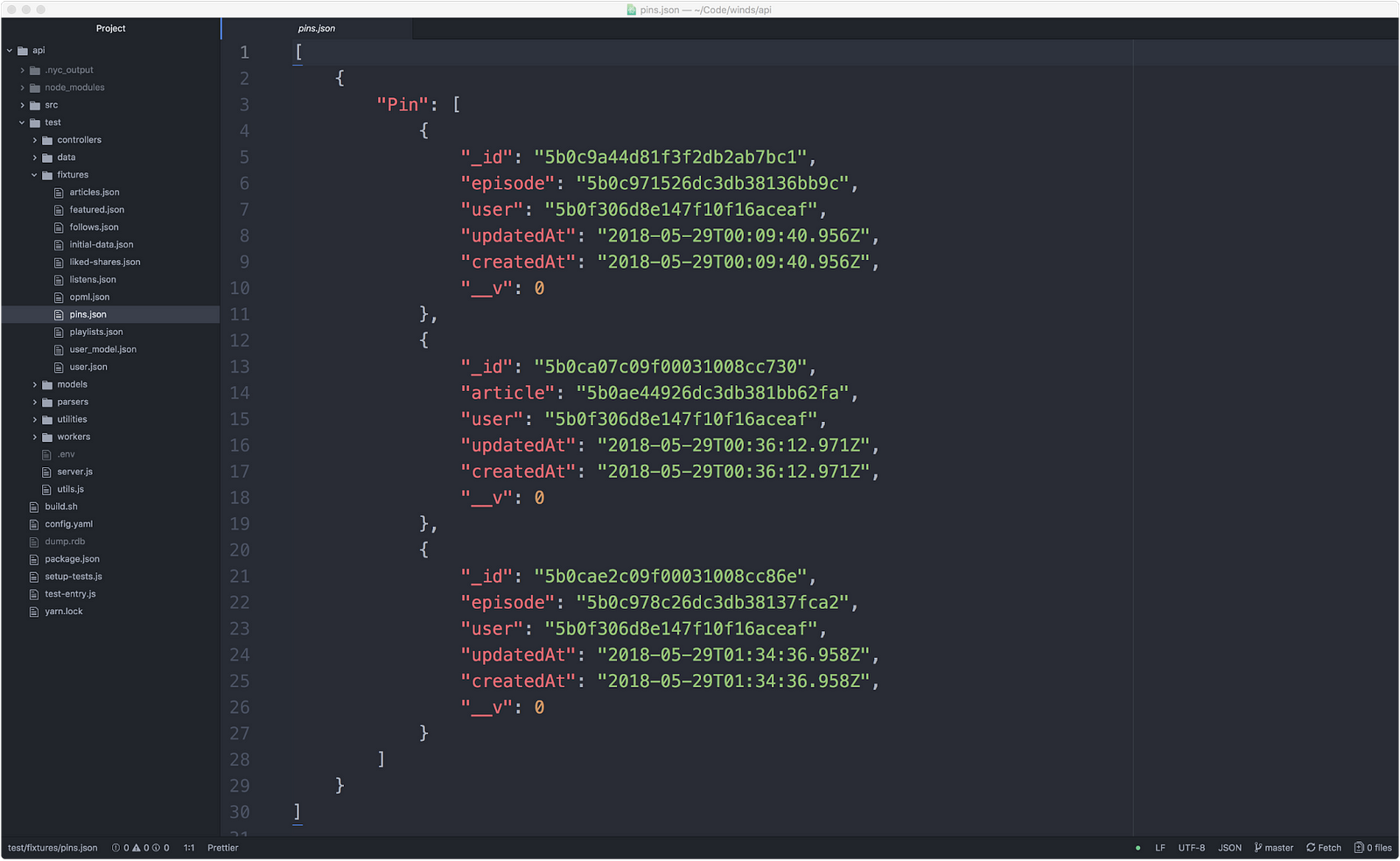

While this isn’t part of the test runner, having a fixture loader is an important part of our test suite. We examined existing solutions; however, we settled on writing our own helper so that it was tailored to our requirements. With our solution, we can load fixtures with complex data-dependencies by following an easy ad-hoc convention when generating or writing fixtures by hand.

|

||

|

||

### Tooling for Winds

|

||

|

||

Although the process was cumbersome, we were able to find the right balance of tools and frameworks to make proper testing become a reality for our backend API. Here’s what we chose to go with:

|

||

|

||

### Mocha ☕

|

||

|

||

[Mocha][6], described as a “feature-rich JavaScript test framework running on Node.js”, was our immediate choice of tooling for the job. With well over 15k stars, many backers, sponsors, and contributors, we knew it was the right framework for the job.

|

||

|

||

### Chai 🥃

|

||

|

||

Next up was our assertion library. We chose to go with the traditional approach, which is what works best with Mocha — [Chai][7]. Chai is a BDD and TDD assertion library for Node.js. With a simple API, Chai was easy to integrate into our application and allowed for us to easily assert what we should _expect_ tobe returned from the Winds API. Best of all, writing tests feel natural with Chai. Here’s a short example:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

describe('retrieve user', () => {

|

||

let user;

|

||

|

||

before(async () => {

|

||

await loadFixture('user');

|

||

user = await User.findOne({email: authUser.email});

|

||

expect(user).to.not.be.null;

|

||

});

|

||

|

||

after(async () => {

|

||

await User.remove().exec();

|

||

});

|

||

|

||

describe('valid request', () => {

|

||

it('should return 200 and the user resource, including the email field, when retrieving the authenticated user', async () => {

|

||

const response = await withLogin(request(api).get(`/users/${user._id}`), authUser);

|

||

|

||

expect(response).to.have.status(200);

|

||

expect(response.body._id).to.equal(user._id.toString());

|

||

});

|

||

|

||

it('should return 200 and the user resource, excluding the email field, when retrieving another user', async () => {

|

||

const anotherUser = await User.findOne({email: 'another_user@email.com'});

|

||

|

||

const response = await withLogin(request(api).get(`/users/${anotherUser.id}`), authUser);

|

||

|

||

expect(response).to.have.status(200);

|

||

expect(response.body._id).to.equal(anotherUser._id.toString());

|

||

expect(response.body).to.not.have.an('email');

|

||

});

|

||

|

||

});

|

||

|

||

describe('invalid requests', () => {

|

||

|

||

it('should return 404 if requested user does not exist', async () => {

|

||

const nonExistingId = '5b10e1c601e9b8702ccfb974';

|

||

expect(await User.findOne({_id: nonExistingId})).to.be.null;

|

||

|

||

const response = await withLogin(request(api).get(`/users/${nonExistingId}`), authUser);

|

||

expect(response).to.have.status(404);

|

||

});

|

||

});

|

||

|

||

});

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

### Sinon 🧙

|

||

|

||

With the ability to work with any unit testing framework, [Sinon][8] was our first choice for a mocking library. Again, a super clean integration with minimal setup, Sinon turns mocking requests into a simple and easy process. Their website has an extremely friendly user experience and offers up easy steps to integrate Sinon with your test suite.

|

||

|

||

### Nock 🔮

|

||

|

||

For all external HTTP requests, we use [nock][9], a robust HTTP mocking library that really comes in handy when you have to communicate with a third party API (such as [Stream’s REST API][10]). There’s not much to say about this little library aside from the fact that it is awesome at what it does, and that’s why we like it. Here’s a quick example of us calling our [personalization][11] engine for Stream:

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

nock(config.stream.baseUrl)

|

||

.get(/winds_article_recommendations/)

|

||

.reply(200, { results: [{foreign_id:`article:${article.id}`}] });

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

### Mock-require 🎩

|

||

|

||

The library [mock-require][12] allows dependencies on external code. In a single line of code, you can replace a module and mock-require will step in when some code attempts to import that module. It’s a small and minimalistic, but robust library, and we’re big fans.

|

||

|

||

### Istanbul 🔭

|

||

|

||

[Istanbul][13] is a JavaScript code coverage tool that computes statement, line, function and branch coverage with module loader hooks to transparently add coverage when running tests. Although we have similar functionality with CodeCov (see next section), this is a nice tool to have when running tests locally.

|

||

|

||

### The End Result — Working Tests

|

||

|

||

_With all of the libraries, including the test runner mentioned above, let’s have a look at what a full test looks like (you can have a look at our entire test suite _ [_here_][14] _):_

|

||

|

||

```

|

||

import nock from 'nock';

|

||

import { expect, request } from 'chai';

|

||

|

||

import api from '../../src/server';

|

||

import Article from '../../src/models/article';

|

||

import config from '../../src/config';

|

||

import { dropDBs, loadFixture, withLogin } from '../utils.js';

|

||

|

||

describe('Article controller', () => {

|

||

let article;

|

||

|

||

before(async () => {

|

||

await dropDBs();

|

||

await loadFixture('initial-data', 'articles');

|

||

article = await Article.findOne({});

|

||

expect(article).to.not.be.null;

|

||

expect(article.rss).to.not.be.null;

|

||

});

|

||

|

||

describe('get', () => {

|

||

it('should return the right article via /articles/:articleId', async () => {

|

||

let response = await withLogin(request(api).get(`/articles/${article.id}`));

|

||

expect(response).to.have.status(200);

|

||

});

|

||

});

|

||

|

||

describe('get parsed article', () => {

|

||

it('should return the parsed version of the article', async () => {

|

||

const response = await withLogin(

|

||

request(api).get(`/articles/${article.id}`).query({ type: 'parsed' })

|

||

);

|

||

expect(response).to.have.status(200);

|

||

});

|

||

});

|

||

|

||

describe('list', () => {

|

||

it('should return the list of articles', async () => {

|

||

let response = await withLogin(request(api).get('/articles'));

|

||

expect(response).to.have.status(200);

|

||

});

|

||

});

|

||

|

||

describe('list from personalization', () => {

|

||

after(function () {

|

||

nock.cleanAll();

|

||

});

|

||

|

||

it('should return the list of articles', async () => {

|

||

nock(config.stream.baseUrl)

|

||

.get(/winds_article_recommendations/)

|

||

.reply(200, { results: [{foreign_id:`article:${article.id}`}] });

|

||

|

||

const response = await withLogin(

|

||

request(api).get('/articles').query({

|

||

type: 'recommended',

|

||

})

|

||

);

|

||

expect(response).to.have.status(200);

|

||

expect(response.body.length).to.be.at.least(1);

|

||

expect(response.body[0].url).to.eq(article.url);

|

||

});

|

||

});

|

||

});

|

||

```

|

||

|

||

### Continuous Integration

|

||

|

||

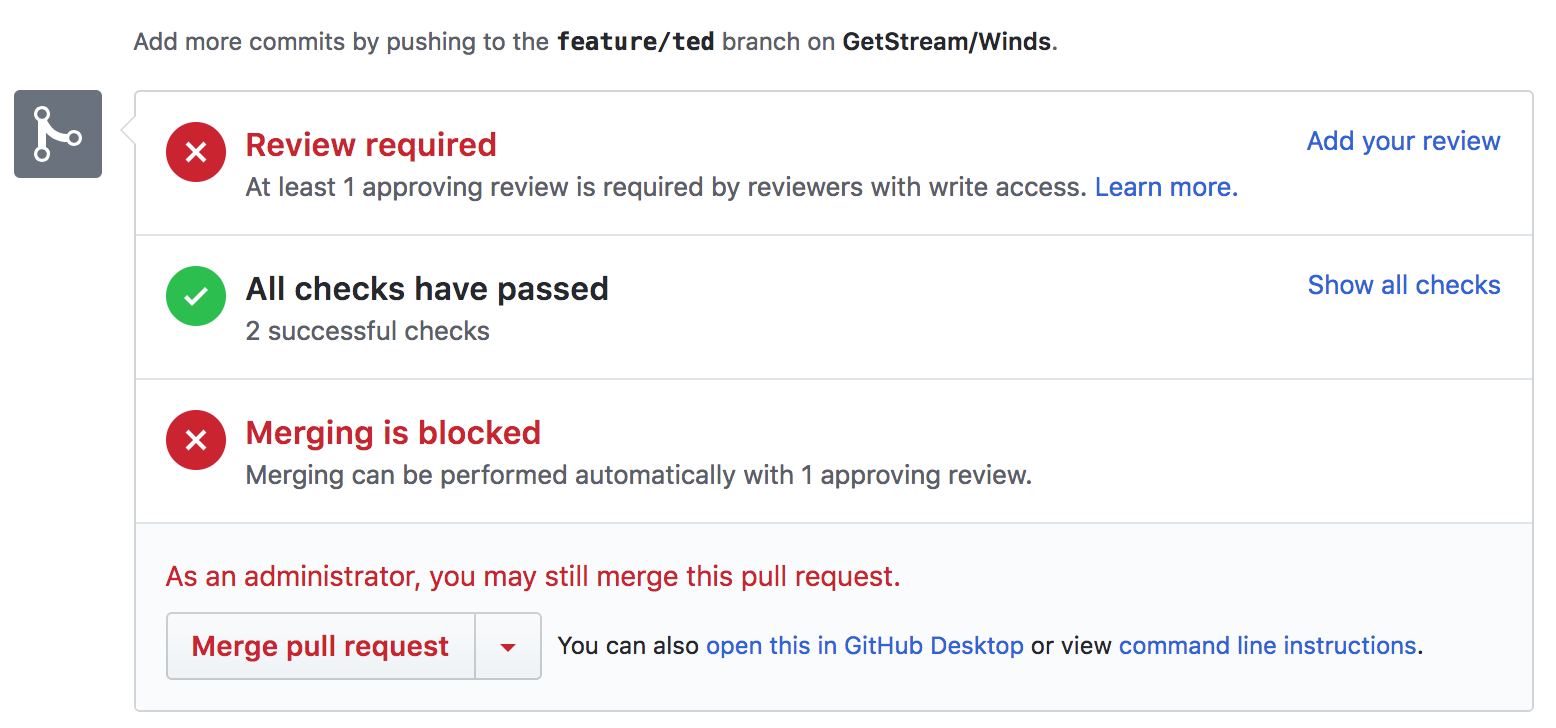

There are a lot of continuous integration services available, but we like to use [Travis CI][15] because they love the open-source environment just as much as we do. Given that Winds is open-source, it made for a perfect fit.

|

||

|

||

Our integration is rather simple — we have a [.travis.yml][16] file that sets up the environment and kicks off our tests via a simple [npm][17] command. The coverage reports back to GitHub, where we have a clear picture of whether or not our latest codebase or PR passes our tests. The GitHub integration is great, as it is visible without us having to go to Travis CI to look at the results. Below is a screenshot of GitHub when viewing the PR (after tests):

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

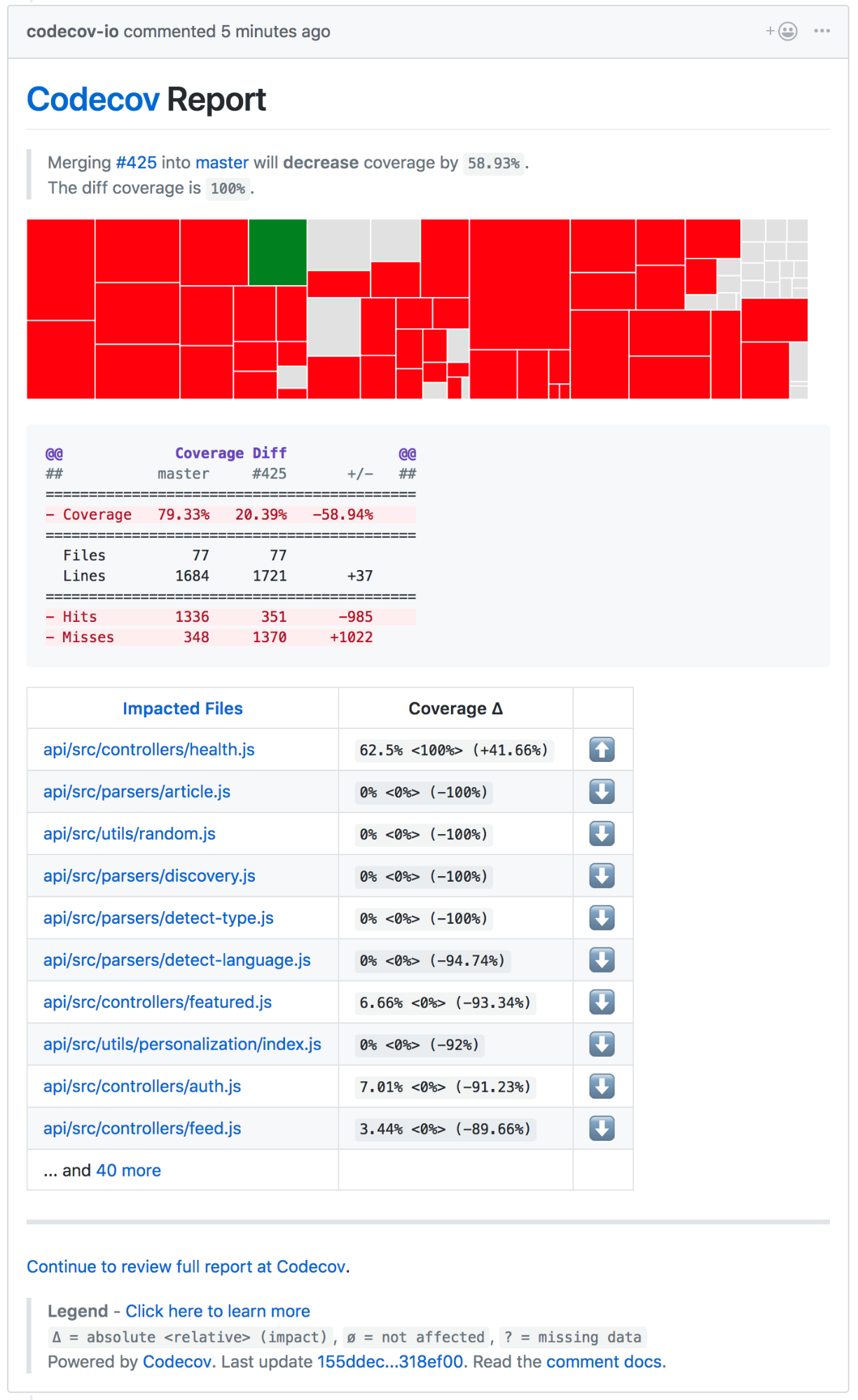

In addition to Travis CI, we use a tool called [CodeCov][18]. CodeCov is similar to [Istanbul][19], however, it’s a visualization tool that allows us to easily see code coverage, files changed, lines modified, and all sorts of other goodies. Though visualizing this data is possible without CodeCov, it’s nice to have everything in one spot.

|

||

|

||

### What We Learned

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

We learned a lot throughout the process of developing our test suite. With no “correct” way of doing things, we decided to set out and create our own test flow by sorting through the available libraries to find ones that were promising enough to add to our toolbox.

|

||

|

||

What we ultimately learned is that testing in Node.js is not as easy as it may sound. Hopefully, as Node.js continues to grow, the community will come together and build a rock solid library that handles everything test related in a “correct” manner.

|

||

|

||

Until then, we’ll continue to use our test suite, which is open-source on the [Winds GitHub repository][20].

|

||

|

||

### Limitations

|

||

|

||

#### No Easy Way to Create Fixtures

|

||

|

||

Frameworks and languages, such as Python’s Django, have easy ways to create fixtures. With Django, for example, you can use the following commands to automate the creation of fixtures by dumping data into a file:

|

||

|

||

The Following command will dump the whole database into a db.json file:

|

||

./manage.py dumpdata > db.json

|

||

|

||

The Following command will dump only the content in django admin.logentry table:

|

||

./manage.py dumpdata admin.logentry > logentry.json

|

||

|

||

The Following command will dump the content in django auth.user table: ./manage.py dumpdata auth.user > user.json

|

||

|

||

There’s no easy way to create a fixture in Node.js. What we ended up doing is using MongoDB Compass and exporting JSON from there. This resulted in a nice fixture, as shown below (however, it was a tedious process and prone to error):

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

#### Unintuitive Module Loading When Using Babel, Mocked Modules, and Mocha Test-Runner

|

||

|

||

To support a broader variety of node versions and have access to latest additions to Javascript standard, we are using Babel to transpile our ES6 codebase to ES5\. Node.js module system is based on the CommonJS standard whereas the ES6 module system has different semantics.

|

||

|

||

Babel emulates ES6 module semantics on top of the Node.js module system, but because we are interfering with module loading by using mock-require, we are embarking on a journey through weird module loading corner cases, which seem unintuitive and can lead to multiple independent versions of the module imported and initialized and used throughout the codebase. This complicates mocking and global state management during testing.

|

||

|

||

#### Inability to Mock Functions Used Within the Module They Are Declared in When Using ES6 Modules

|

||

|

||

When a module exports multiple functions where one calls the other, it’s impossible to mock the function being used inside the module. The reason is that when you require an ES6 module you are presented with a separate set of references from the one used inside the module. Any attempt to rebind the references to point to new values does not really affect the code inside the module, which will continue to use the original function.

|

||

|

||

### Final Thoughts

|

||

|

||

Testing Node.js applications is a complicated process because the ecosystem is always evolving. It’s important to stay on top of the latest and greatest tools so you don’t fall behind.

|

||

|

||

There are so many outlets for JavaScript related news these days that it’s hard to keep up to date with all of them. Following email newsletters such as [JavaScript Weekly][21] and [Node Weekly][22] is a good start. Beyond that, joining a subreddit such as [/r/node][23] is a great idea. If you like to stay on top of the latest trends, [State of JS][24] does a great job at helping developers visualize trends in the testing world.

|

||

|

||

Lastly, here are a couple of my favorite blogs where articles often popup:

|

||

|

||

* [Hacker Noon][1]

|

||

|

||

* [Free Code Camp][2]

|

||

|

||

* [Bits and Pieces][3]

|

||

|

||

Think I missed something important? Let me know in the comments, or on Twitter – [@NickParsons][25].

|

||

|

||

Also, if you’d like to check out Stream, we have a great 5 minute tutorial on our website. Give it a shot [here][26].

|

||

|

||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||

|

||

作者简介:

|

||

|

||

Nick Parsons

|

||

|

||

Dreamer. Doer. Engineer. Developer Evangelist https://getstream.io.

|

||

|

||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||

|

||

via: https://hackernoon.com/testing-node-js-in-2018-10a04dd77391

|

||

|

||

作者:[Nick Parsons][a]

|

||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||

|

||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||

|

||

[a]:https://hackernoon.com/@nparsons08?source=post_header_lockup

|

||

[1]:https://hackernoon.com/

|

||

[2]:https://medium.freecodecamp.org/

|

||

[3]:https://blog.bitsrc.io/

|

||

[4]:https://getstream.io/

|

||

[5]:https://getstream.io/winds

|

||

[6]:https://github.com/mochajs/mocha

|

||

[7]:http://www.chaijs.com/

|

||

[8]:http://sinonjs.org/

|

||

[9]:https://github.com/node-nock/nock

|

||

[10]:https://getstream.io/docs_rest/

|

||

[11]:https://getstream.io/personalization

|

||

[12]:https://github.com/boblauer/mock-require

|

||

[13]:https://github.com/gotwarlost/istanbul

|

||

[14]:https://github.com/GetStream/Winds/tree/master/api/test

|

||

[15]:https://travis-ci.org/

|

||

[16]:https://github.com/GetStream/Winds/blob/master/.travis.yml

|

||

[17]:https://www.npmjs.com/

|

||

[18]:https://codecov.io/#features

|

||

[19]:https://github.com/gotwarlost/istanbul

|

||

[20]:https://github.com/GetStream/Winds/tree/master/api/test

|

||

[21]:https://javascriptweekly.com/

|

||

[22]:https://nodeweekly.com/

|

||

[23]:https://www.reddit.com/r/node/

|

||

[24]:https://stateofjs.com/2017/testing/results/

|

||

[25]:https://twitter.com/@nickparsons

|

||

[26]:https://getstream.io/try-the-api

|