Translating by Flowsnow

Modern Web Automation With Python and Selenium – Real Python

======

In this tutorial you’ll learn advanced Python web automation techniques: Using Selenium with a “headless” browser, exporting the scraped data to CSV files, and wrapping your scraping code in a Python class.

### Motivation: Tracking Listening Habits

Suppose that you have been listening to music on [bandcamp][4] for a while now, and you find yourself wishing you could remember a song you heard a few months back.

Sure you could dig through your browser history and check each song, but that might be a pain… All you remember is that you heard the song a few months ago and that it was in the electronic genre.

“Wouldn’t it be great,” you think to yourself, “if I had a record of my listening history? I could just look up the electronic songs from two months ago and I’d surely find it.”

**Today, you will build a basic Python class, called`BandLeader` that connects to [bandcamp.com][4], streams music from the “discovery” section of the front page, and keeps track of your listening history.**

The listening history will be saved to disk in a [CSV][5] file. You can then explore that CSV file in your favorite spreadsheet application or even with Python.

If you have had some experience with [web scraping in Python][6], you are familiar with making HTTP requests and using Pythonic APIs to navigate the DOM. You will do more of the same today, except with one difference.

**Today you will use a full-fledged browser running in headless mode to do the HTTP requests for you.**

A [headless browser][7] is just a regular web browser, except that it contains no visible UI element. Just like you’d expect, it can do more than make requests: it can also render HTML (though you cannot see it), keep session information, and even perform asynchronous network communications by running JavaScript code.

If you want to automate the modern web, headless browsers are essential.

**Free Bonus:** [Click here to download a "Python + Selenium" project skeleton with full source code][1] that you can use as a foundation for your own Python web scraping and automation apps.

### Setup

Your first step, before writing a single line of Python, is to install a [Selenium][8] supported [WebDriver][9] for your favorite web browser. In what follows, you will be working with [Firefox][10], but [Chrome][11] could easily work too.

So, assuming that the path `~/.local/bin` is in your execution `PATH`, here’s how you would install the Firefox webdriver, called `geckodriver`, on a Linux machine:

```

$ wget https://github.com/mozilla/geckodriver/releases/download/v0.19.1/geckodriver-v0.19.1-linux64.tar.gz

$ tar xvfz geckodriver-v0.19.1-linux64.tar.gz

$ mv geckodriver ~/.local/bin

```

Next, you install the [selenium][12] package, using `pip` or however else you like. If you made a [virtual environment][13] for this project, you just type:

```

$ pip install selenium

```

[ If you ever feel lost during the course of this tutorial, the full code demo can be found [on GitHub][14]. ]

Now it’s time for a test drive:

### Test Driving a Headless Browser

To test that everything is working, you decide to try out a basic web search via [DuckDuckGo][15]. You fire up your preferred Python interpreter and type:

```

>>> from selenium.webdriver import Firefox

>>> from selenium.webdriver.firefox.options import Options

>>> opts = Options()

>>> opts.set_headless()

>>> assert options.headless # operating in headless mode

>>> browser = Firefox(options=opts)

>>> browser.get('https://duckduckgo.com')

```

So far you have created a headless Firefox browser navigated to `https://duckduckgo.com`. You made an `Options` instance and used it to activate headless mode when you passed it to the `Firefox` constructor. This is akin to typing `firefox -headless` at the command line.

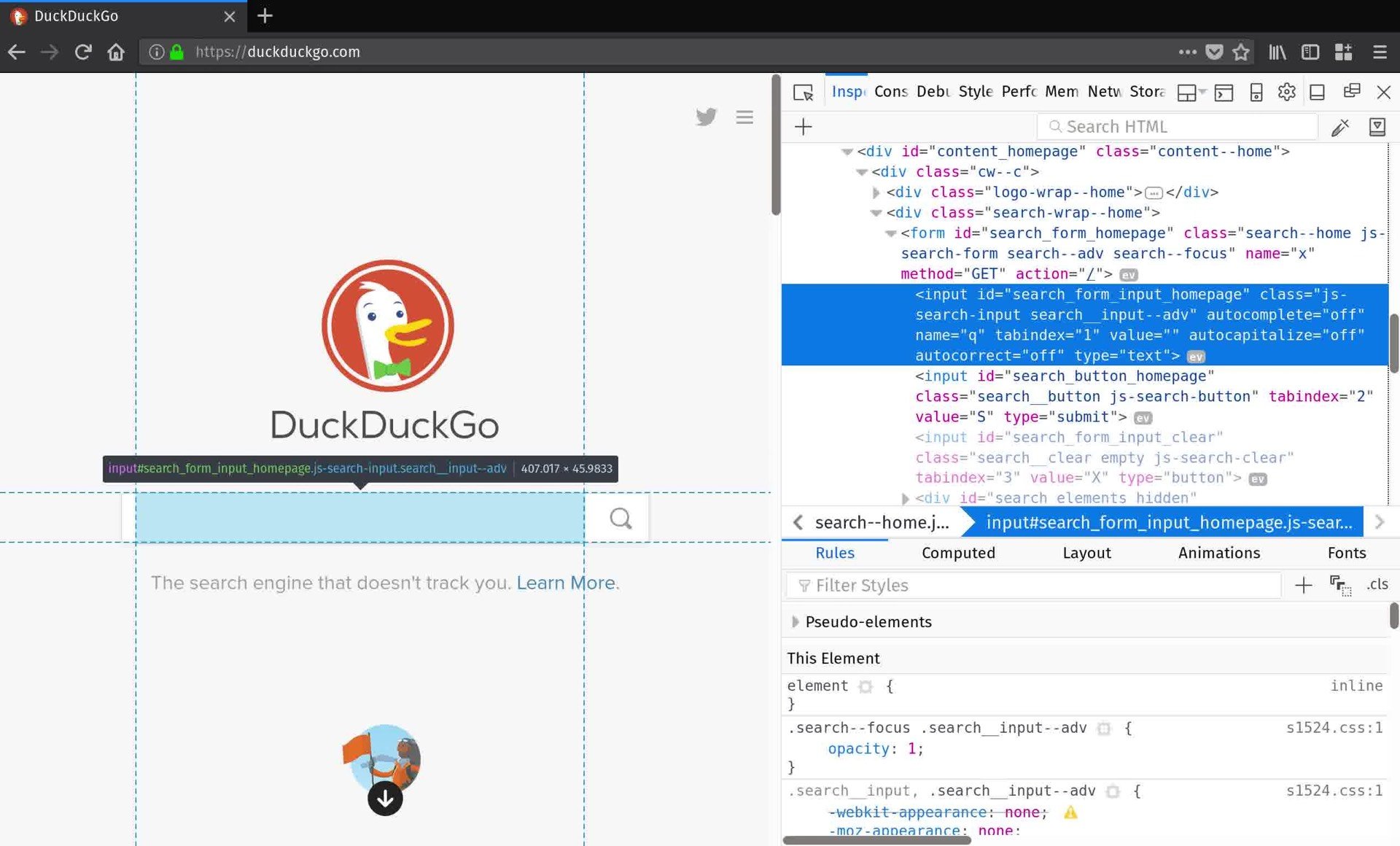

Now that a page is loaded you can query the DOM using methods defined on your newly minted `browser` object. But how do you know what to query? The best way is to open your web browser and use its developer tools to inspect the contents of the page. Right now you want to get ahold of the search form so you can submit a query. By inspecting DuckDuckGo’s home page you find that the search form `` element has an `id` attribute `"search_form_input_homepage"`. That’s just what you needed:

```

>>> search_form = browser.find_element_by_id('search_form_input_homepage')

>>> search_form.send_keys('real python')

>>> search_form.submit()

```

You found the search form, used the `send_keys` method to fill it out, and then the `submit` method to perform your search for `"Real Python"`. You can checkout the top result:

```

>>> results = browser.find_elements_by_class_name('result')

>>> print(results[0].text)

Real Python - Real Python

Get Real Python and get your hands dirty quickly so you spend more time making real applications. Real Python teaches Python and web development from the ground up ...

https://realpython.com

```

Everything seems to be working. In order to prevent invisible headless browser instances from piling up on your machine, you close the browser object before exiting your python session:

```

>>> browser.close()

>>> quit()

```

### Groovin on Tunes

You’ve tested that you can drive a headless browser using Python, now to put it to use.

1. You want to play music

2. You want to browse and explore music

3. You want information about what music is playing.

To start, you navigate to and start to poke around in your browser’s developer tools. You discover a big shiny play button towards the bottom of the screen with a `class` attribute that contains the value`"playbutton"`. You check that it works:

```

>>> opts = Option()

>>> opts.set_headless()

>>> browser = Firefox(options=opts)

>>> browser.get('https://bandcamp.com')

>>> browser.find_element_by_class('playbutton').click()

```

You should hear music! Leave it playing and move back to your web browser. Just to the side of the play button is the discovery section. Again, you inspect this section and find that each of the currently visible available tracks has a `class` value of `"discover-item"`, and that each item seems to be clickable. In Python, you check this out:

```

>>> tracks = browser.find_elements_by_class_name('discover-item')

>>> len(tracks) # 8

>>> tracks[3].click()

```

A new track should be playing! This is the first step to exploring bandcamp using Python! You spend a few minutes clicking on different tracks in your Python environment but soon grow tired of the meagre library of 8 songs.

### Exploring the Catalogue

Looking a back at your browser, you see the buttons for exploring all of the tracks featured in bandcamp’s music discovery section. By now this feels familiar: each button has a `class` value of `"item-page"`. The very last button is the “next” button that will display the next eight tracks in the catalogue. You go to work:

```

>>> next_button = [e for e in browser.find_elements_by_class_name('item-page')

if e.text.lower().find('next') > -1]

>>> next_button.click()

```

Great! Now you want to look at the new tracks, so you think “I’ll just repopulate my `tracks` variable like I did a few minutes ago”. But this is where things start to get tricky.

First, bandcamp designed their site for humans to enjoy using, not for Python scripts to access programmatically. When you call `next_button.click()` the real web browser responds by executing some JavaScript code. If you try it out in your browser, you see that some time elapses as the catalogue of songs scrolls with a smooth animation effect. If you try to repopulate your `tracks` variable before the animation finishes, you may not get all the tracks and you may get some that you don’t want.

The solution? You can just sleep for a second or, if you are just running all this in a Python shell, you probably wont even notice - after all it takes time for you to type too.

Another slight kink is something that can only be discovered through experimentation. You try to run the same code again:

```

>>> tracks = browser.find_elements_by_class_name('discover-item')

>>> assert(len(tracks) == 8)

AssertionError

...

```

But you notice something strange. `len(tracks)` is not equal to `8` even though only the next batch of `8` should be displayed. Digging a little further you find that your list contains some tracks that were displayed before. To get only the tracks that are actually visible in the browser, you need to filter the results a little.

After trying a few things, you decide to keep a track only if its `x` coordinate on the page fall within the bounding box of the containing element. The catalogue’s container has a `class` value of `"discover-results"`. Here’s how you proceed:

```

>>> discover_section = self.browser.find_element_by_class_name('discover-results')

>>> left_x = discover_section.location['x']

>>> right_x = left_x + discover_section.size['width']

>>> discover_items = browser.find_element_by_class_name('discover_items')

>>> tracks = [t for t in discover_items

if t.location['x'] >= left_x and t.location['x'] < right_x]

>>> assert len(tracks) == 8

```

### Building a Class

If you are growing weary of retyping the same commands over and over again in your Python environment, you should dump some of it into a module. A basic class for your bandcamp manipulation should do the following:

1. Initialize a headless browser and navigate to bandcamp

2. Keep a list of available tracks

3. Support finding more tracks

4. Play, pause, and skip tracks

All in one go, here’s the basic code:

```

from selenium.webdriver import Firefox

from selenium.webdriver.firefox.options import Options

from time import sleep, ctime

from collections import namedtuple

from threading import Thread

from os.path import isfile

import csv

BANDCAMP_FRONTPAGE='https://bandcamp.com/'

class BandLeader():

def __init__(self):

# create a headless browser

opts = Options()

opts.set_headless()

self.browser = Firefox(options=opts)

self.browser.get(BANDCAMP_FRONTPAGE)

# track list related state

self._current_track_number = 1

self.track_list = []

self.tracks()

def tracks(self):

'''

query the page to populate a list of available tracks

'''

# sleep to give the browser time to render and finish any animations

sleep(1)

# get the container for the visible track list

discover_section = self.browser.find_element_by_class_name('discover-results')

left_x = discover_section.location['x']

right_x = left_x + discover_section.size['width']

# filter the items in the list to include only those we can click

discover_items = self.browser.find_elements_by_class_name('discover-item')

self.track_list = [t for t in discover_items

if t.location['x'] >= left_x and t.location['x'] < right_x]

# print the available tracks to the screen

for (i,track) in enumerate(self.track_list):

print('[{}]'.format(i+1))

lines = track.text.split('\n')

print('Album : {}'.format(lines[0]))

print('Artist : {}'.format(lines[1]))

if len(lines) > 2:

print('Genre : {}'.format(lines[2]))

def catalogue_pages(self):

'''

print the available pages in the catalogue that are presently

accessible

'''

print('PAGES')

for e in self.browser.find_elements_by_class_name('item-page'):

print(e.text)

print('')

def more_tracks(self,page='next'):

'''

advances the catalog and repopulates the track list, we can pass in a number

to advance any of hte available pages

'''

next_btn = [e for e in self.browser.find_elements_by_class_name('item-page')

if e.text.lower().strip() == str(page)]

if next_btn:

next_btn[0].click()

self.tracks()

def play(self,track=None):

'''

play a track. If no track number is supplied, the presently selected track

will play

'''

if track is None:

self.browser.find_element_by_class_name('playbutton').click()

elif type(track) is int and track <= len(self.track_list) and track >= 1:

self._current_track_number = track

self.track_list[self._current_track_number - 1].click()

def play_next(self):

'''

plays the next available track

'''

if self._current_track_number < len(self.track_list):

self.play(self._current_track_number+1)

else:

self.more_tracks()

self.play(1)

def pause(self):

'''

pauses the playback

'''

self.play()

```

Pretty neat. You can import this into your Python environment and run bandcamp programmatically! But wait, didn’t you start this whole thing because you wanted to keep track of information about your listening history?

### Collecting Structured Data

Your final task is to keep track of the songs that you actually listened to. How might you do this? What does it mean to actually listen to something anyway? If you are perusing the catalogue, stopping for a few seconds on each song, do each of those songs count? Probably not. You are going to allow some ‘exploration’ time to factor in to your data collection.

Your goals are now to:

1. Collect structured information about the currently playing track

2. Keep a “database” of tracks

3. Save and restore that “database” to and from disk

You decide to use a [namedtuple][16] to store the information that you track. Named tuples are good for representing bundles of attributes with no functionality tied to them, a bit like a database record.

```

TrackRec = namedtuple('TrackRec', [

'title',

'artist',

'artist_url',

'album',

'album_url',

'timestamp' # When you played it

])

```

In order to collect this information, you add a method to the `BandLeader` class. Checking back in with the browser’s developer tools, you find the right HTML elements and attributes to select all the information you need. Also, you only want to get information about the currently playing track if there music is actually playing at the time. Luckily, the page player adds a `"playing"` class to the play button whenever music is playing and removes it when the music stops. With these considerations in mind, you write a couple of methods:

```

def is_playing(self):

'''

returns `True` if a track is presently playing

'''

playbtn = self.browser.find_element_by_class_name('playbutton')

return playbtn.get_attribute('class').find('playing') > -1

def currently_playing(self):

'''

Returns the record for the currently playing track,

or None if nothing is playing

'''

try:

if self.is_playing():

title = self.browser.find_element_by_class_name('title').text

album_detail = self.browser.find_element_by_css_selector('.detail-album > a')

album_title = album_detail.text

album_url = album_detail.get_attribute('href').split('?')[0]

artist_detail = self.browser.find_element_by_css_selector('.detail-artist > a')

artist = artist_detail.text

artist_url = artist_detail.get_attribute('href').split('?')[0]

return TrackRec(title, artist, artist_url, album_title, album_url, ctime())

except Exception as e:

print('there was an error: {}'.format(e))

return None

```

For good measure, you also modify the `play` method to keep track of the currently playing track:

```

def play(self, track=None):

'''

play a track. If no track number is supplied, the presently selected track

will play

'''

if track is None:

self.browser.find_element_by_class_name('playbutton').click()

elif type(track) is int and track <= len(self.track_list) and track >= 1:

self._current_track_number = track

self.track_list[self._current_track_number - 1].click()

sleep(0.5)

if self.is_playing():

self._current_track_record = self.currently_playing()

```

Next, you’ve got to keep a database of some kind. Though it may not scale well in the long run, you can go far with a simple list. You add `self.database = []` to `BandCamp`‘s `__init__` method. Because you want to allow for time to pass before entering a `TrackRec` object into the database, you decide to use Python’s [threading tools][17] to run a separate process that maintains the database in the background.

You’ll supply a `_maintain()` method to `BandLeader` instances that will run it a separate thread. The new method will periodically check the value of `self._current_track_record` and add it to the database if it is new.

You will start the thread when the class is instantiated by adding some code to `__init__`.

```

# the new init

def __init__(self):

# create a headless browser

opts = Options()

opts.set_headless()

self.browser = Firefox(options=opts)

self.browser.get(BANDCAMP_FRONTPAGE)

# track list related state

self._current_track_number = 1

self.track_list = []

self.tracks()

# state for the database

self.database = []

self._current_track_record = None

# the database maintenance thread

self.thread = Thread(target=self._maintain)

self.thread.daemon = True # kills the thread with the main process dies

self.thread.start()

self.tracks()

def _maintain(self):

while True:

self._update_db()

sleep(20) # check every 20 seconds

def _update_db(self):

try:

check = (self._current_track_record is not None

and (len(self.database) == 0

or self.database[-1] != self._current_track_record)

and self.is_playing())

if check:

self.database.append(self._current_track_record)

except Exception as e:

print('error while updating the db: {}'.format(e)

```

If you’ve never worked with multithreaded programming in Python, [you should read up on it!][18] For your present purpose, you can think of thread as a loop that runs in the background of the main Python process (the one you interact with directly). Every twenty seconds, the loop checks a few things to see if the database needs to be updated, and if it does, appends a new record. Pretty cool.

The very last step is saving the database and restoring from saved states. Using the [csv][19] package you can ensure your database resides in a highly portable format, and remains usable even if you abandon your wonderful `BandLeader` class ;)

The `__init__` method should be yet again altered, this time to accept a file path where you’d like to save the database. You’d like to load this database if it is available, and you’d like to save it periodically, whenever it is updated. The updates look like so:

```

def __init__(self,csvpath=None):

self.database_path=csvpath

self.database = []

# load database from disk if possible

if isfile(self.database_path):

with open(self.database_path, newline='') as dbfile:

dbreader = csv.reader(dbfile)

next(dbreader) # to ignore the header line

self.database = [TrackRec._make(rec) for rec in dbreader]

# .... the rest of the __init__ method is unchanged ....

# a new save_db method

def save_db(self):

with open(self.database_path,'w',newline='') as dbfile:

dbwriter = csv.writer(dbfile)

dbwriter.writerow(list(TrackRec._fields))

for entry in self.database:

dbwriter.writerow(list(entry))

# finally add a call to save_db to your database maintenance method

def _update_db(self):

try:

check = (self._current_track_record is not None

and self._current_track_record is not None

and (len(self.database) == 0

or self.database[-1] != self._current_track_record)

and self.is_playing())

if check:

self.database.append(self._current_track_record)

self.save_db()

except Exception as e:

print('error while updating the db: {}'.format(e)

```

And voilà! You can listen to music and keep a record of what you hear! Amazing.

Something interesting about the above is that [using a `namedtuple`][16] really begins to pay off. When converting to and from CSV format, you take advantage of the ordering of the rows in the CSV file to fill in the rows in the `TrackRec` objects. Likewise, you can create the header row of the CSV file by referencing the `TrackRec._fields` attribute. This is one of the reasons using a tuple ends up making sense for columnar data.

### What’s Next and What Have You Learned?

From here you could do loads more! Here are a few quick ideas that would leverage the mild superpower that is Python + Selenium:

* You could extend the `BandLeader` class to navigate to album pages and play the tracks you find there

* You might decide to create playlists based on your favorite or most frequently heard tracks

* Perhaps you want to add an autoplay feature

* Maybe you’d like to query songs by date or title or artist and build playlists that way

**Free Bonus:** [Click here to download a "Python + Selenium" project skeleton with full source code][1] that you can use as a foundation for your own Python web scraping and automation apps.

You have learned that Python can do everything that a web browser can do, and a bit more. You could easily write scripts to control virtual browser instances that run in the cloud, create bots that interact with real users, or that mindlessly fill out forms! Go forth, and automate!

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

via: https://realpython.com/blog/python/modern-web-automation-with-python-and-selenium/

作者:[Colin OKeefe][a]

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

[a]:https://realpython.com/team/cokeefe/

[1]:https://realpython.com/blog/python/modern-web-automation-with-python-and-selenium/#

[4]:https://bandcamp.com

[5]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comma-separated_values

[6]:https://realpython.com/blog/python/python-web-scraping-practical-introduction/

[7]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Headless_browser

[8]:http://www.seleniumhq.org/docs/

[9]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Selenium_(software)#Selenium_WebDriver

[10]:https://www.mozilla.org/en-US/firefox/new/

[11]:https://www.google.com/chrome/index.html

[12]:http://seleniumhq.github.io/selenium/docs/api/py/

[13]:https://realpython.com/blog/python/python-virtual-environments-a-primer/

[14]:https://github.com/realpython/python-web-scraping-examples

[15]:https://duckduckgo.com

[16]:https://dbader.org/blog/writing-clean-python-with-namedtuples

[17]:https://docs.python.org/3.6/library/threading.html#threading.Thread

[18]:https://dbader.org/blog/python-parallel-computing-in-60-seconds

[19]:https://docs.python.org/3.6/library/csv.html