diff --git a/published/20190830 git exercises- navigate a repository.md b/published/20190830 git exercises- navigate a repository.md

new file mode 100644

index 0000000000..2c7899d172

--- /dev/null

+++ b/published/20190830 git exercises- navigate a repository.md

@@ -0,0 +1,82 @@

+[#]: collector: (lujun9972)

+[#]: translator: (wxy)

+[#]: reviewer: (wxy)

+[#]: publisher: (wxy)

+[#]: url: (https://linux.cn/article-11379-1.html)

+[#]: subject: (git exercises: navigate a repository)

+[#]: via: (https://jvns.ca/blog/2019/08/30/git-exercises--navigate-a-repository/)

+[#]: author: (Julia Evans https://jvns.ca/)

+

+Git 练习:存储库导航

+======

+

+我觉得前几天的 [curl 练习][1]进展顺利,所以今天我醒来后,想尝试编写一些 Git 练习。Git 是一大块需要学习的技能,可能要花几个小时才能学会,所以我分解练习的第一个思路是从“导航”一个存储库开始的。

+

+我本来打算使用一个玩具测试库,但后来我想,为什么不使用真正的存储库呢?这样更有趣!因此,我们将浏览 Ruby 编程语言的存储库。你无需了解任何 C 即可完成此练习,只需熟悉一下存储库中的文件随时间变化的方式即可。

+

+### 克隆存储库

+

+开始之前,需要克隆存储库:

+

+```

+git clone https://github.com/ruby/ruby

+```

+

+与实际使用的大多数存储库相比,该存储库的最大不同之处在于它没有分支,但是它有很多标签,它们与分支相似,因为它们都只是指向一个提交的指针而已。因此,我们将使用标签而不是分支进行练习。*改变*标签的方式和分支非常不同,但*查看*标签和分支的方式完全相同。

+

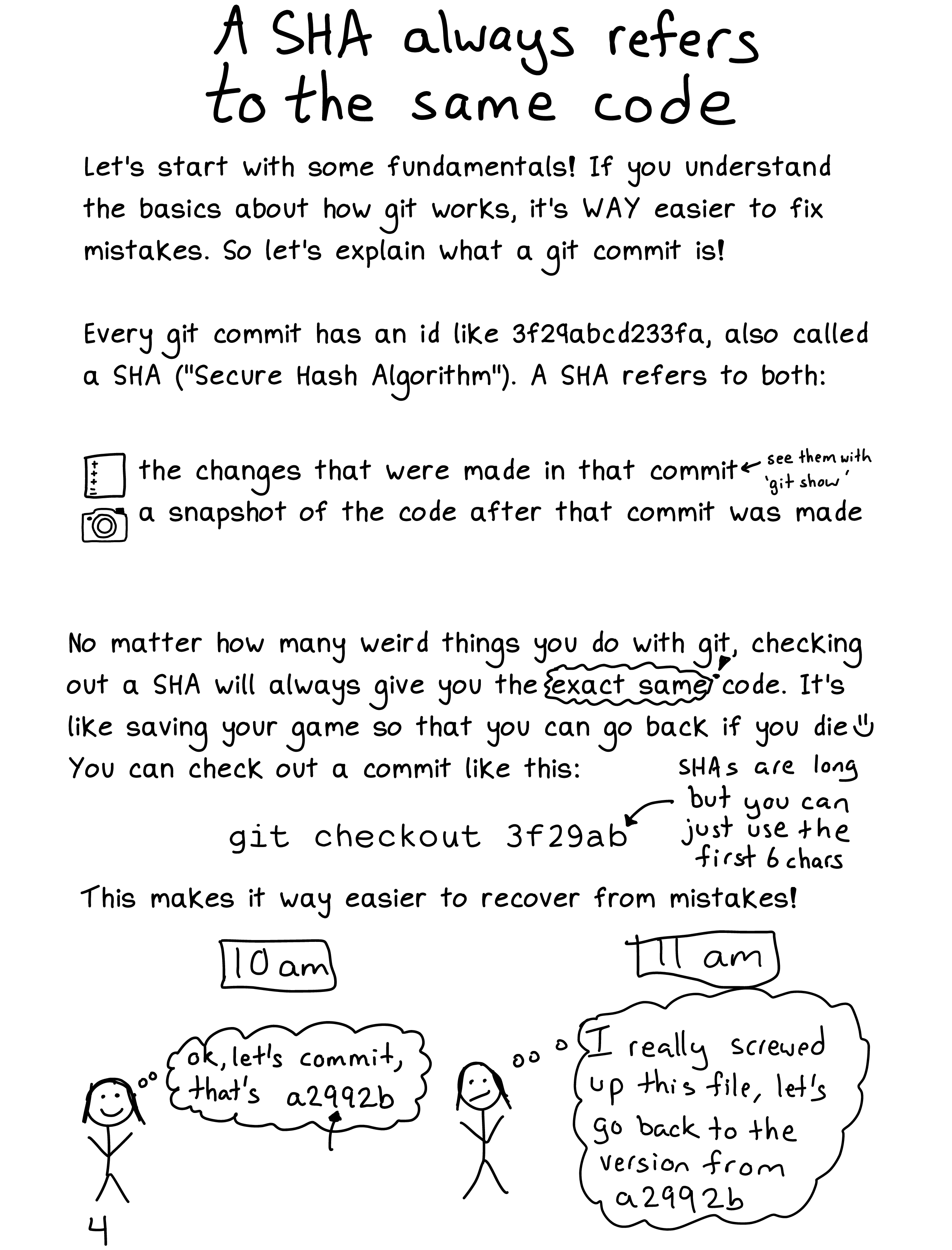

+### Git SHA 总是引用同一个代码

+

+执行这些练习时要记住的最重要的一点是,如本页面所述,像`9e3d9a2a009d2a0281802a84e1c5cc1c887edc71` 这样的 Git SHA 始终引用同一个的代码。下图摘自我与凯蒂·西勒·米勒撰写的一本杂志,名为《[Oh shit, git!][2]》。(她还有一个名为 的很棒的网站,启发了该杂志。)

+

+

+

+我们将在练习中大量使用 Git SHA,以使你习惯于使用它们,并帮助你了解它们与标签和分支的对应关系。

+

+### 我们将要使用的 Git 子命令

+

+所有这些练习仅使用这 5 个 Git 子命令:

+

+```

+git checkout

+git log (--oneline, --author, and -S will be useful)

+git diff (--stat will be useful)

+git show

+git status

+```

+

+### 练习

+

+1. 查看 matz 从 1998 年开始的 Ruby 提交。提交 ID 为 ` 3db12e8b236ac8f88db8eb4690d10e4a3b8dbcd4`。找出当时 Ruby 的代码行数。

+2. 检出当前的 master 分支。

+3. 查看文件 `hash.c` 的历史记录。更改该文件的最后一个提交 ID 是什么?

+4. 了解最近 20 年来 `hash.c` 的变化:将 master 分支上的文件与提交 `3db12e8b236ac8f88db8eb4690d10e4a3b8dbcd4` 的文件进行比较。

+5. 查找最近更改了 `hash.c` 的提交,并查看该提交的差异。

+6. 对于每个 Ruby 版本,该存储库都有一堆**标签**。获取所有标签的列表。

+7. 找出在标签 `v1_8_6_187` 和标签 `v1_8_6_188` 之间更改了多少文件。

+8. 查找 2015 年的提交(任何一个提交)并将其检出,简单地查看一下文件,然后返回 master 分支。

+9. 找出标签 `v1_8_6_187` 对应的提交。

+10. 列出目录 `.git/refs/tags`。运行 `cat .git/refs/tags/v1_8_6_187` 来查看其中一个文件的内容。

+11. 找出当前 `HEAD` 对应的提交 ID。

+12. 找出已经对 `test/` 目录进行了多少次提交。

+13. 提交 `65a5162550f58047974793cdc8067a970b2435c0` 和 `9e3d9a2a009d2a0281802a84e1c5cc1c887edc71` 之间的 `lib/telnet.rb` 的差异。该文件更改了几行?

+14. 在 Ruby 2.5.1 和 2.5.2 之间进行了多少次提交(标记为 `v2_5_1` 和 `v2_5_3`)(这一步有点棘手,步骤不只一步)

+15. “matz”(Ruby 的创建者)作了多少提交?

+16. 最近包含 “tkutil” 一词的提交是什么?

+17. 检出提交 `e51dca2596db9567bd4d698b18b4d300575d3881` 并创建一个指向该提交的新分支。

+18. 运行 `git reflog` 以查看你到目前为止完成的所有存储库导航操作。

+

+--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

+

+via: https://jvns.ca/blog/2019/08/30/git-exercises--navigate-a-repository/

+

+作者:[Julia Evans][a]

+选题:[lujun9972][b]

+译者:[wxy](https://github.com/wxy)

+校对:[wxy](https://github.com/wxy)

+

+本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

+

+[a]: https://jvns.ca/

+[b]: https://github.com/lujun9972

+[1]: https://jvns.ca/blog/2019/08/27/curl-exercises/

+[2]: https://wizardzines.com/zines/oh-shit-git/

diff --git a/sources/tech/20190528 A Quick Look at Elvish Shell.md b/sources/tech/20190528 A Quick Look at Elvish Shell.md

index 778965d442..ba2eb640fd 100644

--- a/sources/tech/20190528 A Quick Look at Elvish Shell.md

+++ b/sources/tech/20190528 A Quick Look at Elvish Shell.md

@@ -1,5 +1,5 @@

[#]: collector: (lujun9972)

-[#]: translator: ( )

+[#]: translator: (geekpi)

[#]: reviewer: ( )

[#]: publisher: ( )

[#]: url: ( )

diff --git a/sources/tech/20190822 How to move a file in Linux.md b/sources/tech/20190822 How to move a file in Linux.md

deleted file mode 100644

index c38f9445e1..0000000000

--- a/sources/tech/20190822 How to move a file in Linux.md

+++ /dev/null

@@ -1,286 +0,0 @@

-[#]: collector: (lujun9972)

-[#]: translator: ( )

-[#]: reviewer: ( )

-[#]: publisher: ( )

-[#]: url: ( )

-[#]: subject: (How to move a file in Linux)

-[#]: via: (https://opensource.com/article/19/8/moving-files-linux-depth)

-[#]: author: (Seth Kenlon https://opensource.com/users/sethhttps://opensource.com/users/doni08521059)

-

-How to move a file in Linux

-======

-Whether you're new to moving files in Linux or experienced, you'll learn

-something in this in-depth writeup.

-![Files in a folder][1]

-

-Moving files in Linux can seem relatively straightforward, but there are more options available than most realize. This article teaches beginners how to move files in the GUI and on the command line, but also explains what’s actually happening under the hood, and addresses command line options that many experience users have rarely explored.

-

-### Moving what?

-

-Before delving into moving files, it’s worth taking a closer look at what actually happens when _moving_ file system objects. When a file is created, it is assigned to an _inode_, which is a fixed point in a file system that’s used for data storage. You can what inode maps to a file with the [ls][2] command:

-

-

-```

-$ ls --inode example.txt

-7344977 example.txt

-```

-

-When you move a file, you don’t actually move the data from one inode to another, you only assign the file object a new name or file path. In fact, a file retains its permissions when it’s moved, because moving a file doesn’t change or re-create it.

-

-File and directory inodes never imply inheritance and are dictated by the filesystem itself. Inode assignment is sequential based on when the file was created and is entirely independent of how you organize your computer. A file "inside" a directory may have a lower inode number than its parent directory, or a higher one. For example:

-

-

-```

-$ mkdir foo

-$ mv example.txt foo

-$ ls --inode

-7476865 foo

-$ ls --inode foo

-7344977 example.txt

-```

-

-When moving a file from one hard drive to another, however, the inode is very likely to change. This happens because the new data has to be written onto a new filesystem. For this reason, in Linux the act of moving and renaming files is literally the same action. Whether you move a file to another directory or to the same directory with a new name, both actions are performed by the same underlying program.

-

-This article focuses on moving files from one directory to another.

-

-### Moving with a mouse

-

-The GUI is a friendly and, to most people, familiar layer of abstraction on top of a complex collection of binary data. It’s also the first and most intuitive way to move files on Linux. If you’re used to the desktop experience, in a generic sense, then you probably already know how to move files around your hard drive. In the GNOME desktop, for instance, the default action when dragging and dropping a file from one window to another is to move the file rather than to copy it, so it’s probably one of the most intuitive actions on the desktop:

-

-![Moving a file in GNOME.][3]

-

-The Dolphin file manager in the KDE Plasma desktop defaults to prompting the user for an action. Holding the **Shift** key while dragging a file forces a move action:

-

-![Moving a file in KDE.][4]

-

-### Moving on the command line

-

-The shell command intended for moving files on Linux, BSD, Illumos, Solaris, and MacOS is **mv**. A simple command with a predictable syntax, **mv <source> <destination>** moves a source file to the specified destination, each defined by either an [absolute][5] or [relative][6] file path. As mentioned before, **mv** is such a common command for [POSIX][7] users that many of its additional modifiers are generally unknown, so this article brings a few useful modifiers to your attention whether you are new or experienced.

-

-Not all **mv** commands were written by the same people, though, so you may have GNU **mv**, BSD **mv**, or Sun **mv**, depending on your operating system. Command options differ from implementation to implementation (BSD **mv** has no long options at all) so refer to your **mv** man page to see what’s supported, or install your preferred version instead (that’s the luxury of open source).

-

-#### Moving a file

-

-To move a file from one folder to another with **mv**, remember the syntax **mv <source> <destination>**. For instance, to move the file **example.txt** into your **Documents** directory:

-

-

-```

-$ touch example.txt

-$ mv example.txt ~/Documents

-$ ls ~/Documents

-example.txt

-```

-

-Just like when you move a file by dragging and dropping it onto a folder icon, this command doesn’t replace **Documents** with **example.txt**. Instead, **mv** detects that **Documents** is a folder, and places the **example.txt** file into it.

-

-You can also, conveniently, rename the file as you move it:

-

-

-```

-$ touch example.txt

-$ mv example.txt ~/Documents/foo.txt

-$ ls ~/Documents

-foo.txt

-```

-

-That’s important because it enables you to rename a file even when you don’t want to move it to another location, like so:

-

-

-```

-`$ touch example.txt $ mv example.txt foo2.txt $ ls foo2.txt`

-```

-

-#### Moving a directory

-

-The **mv** command doesn’t differentiate a file from a directory the way [**cp**][8] does. You can move a directory or a file with the same syntax:

-

-

-```

-$ touch file.txt

-$ mkdir foo_directory

-$ mv file.txt foo_directory

-$ mv foo_directory ~/Documents

-```

-

-#### Moving a file safely

-

-If you copy a file to a directory where a file of the same name already exists, the **mv** command replaces the destination file with the one you are moving, by default. This behavior is called _clobbering_, and sometimes it’s exactly what you intend. Other times, it is not.

-

-Some distributions _alias_ (or you might [write your own][9]) **mv** to **mv --interactive**, which prompts you for confirmation. Some do not. Either way, you can use the **\--interactive** or **-i** option to ensure that **mv** asks for confirmation in the event that two files of the same name are in conflict:

-

-

-```

-$ mv --interactive example.txt ~/Documents

-mv: overwrite '~/Documents/example.txt'?

-```

-

-If you do not want to manually intervene, use **\--no-clobber** or **-n** instead. This flag silently rejects the move action in the event of conflict. In this example, a file named **example.txt** already exists in **~/Documents**, so it doesn't get moved from the current directory as instructed:

-

-

-```

-$ mv --no-clobber example.txt ~/Documents

-$ ls

-example.txt

-```

-

-#### Moving with backups

-

-If you’re using GNU **mv**, there are backup options offering another means of safe moving. To create a backup of any conflicting destination file, use the **-b** option:

-

-

-```

-$ mv -b example.txt ~/Documents

-$ ls ~/Documents

-example.txt example.txt~

-```

-

-This flag ensures that **mv** completes the move action, but also protects any pre-existing file in the destination location.

-

-Another GNU backup option is **\--backup**, which takes an argument defining how the backup file is named:

-

- * **existing**: If numbered backups already exist in the destination, then a numbered backup is created. Otherwise, the **simple** scheme is used.

- * **none**: Does not create a backup even if **\--backup** is set. This option is useful to override a **mv** alias that sets the backup option.

- * **numbered**: Appends the destination file with a number.

- * **simple**: Appends the destination file with a **~**, which can conveniently be hidden from your daily view with the **\--ignore-backups** option for **[ls][2]**.

-

-

-

-For example:

-

-

-```

-$ mv --backup=numbered example.txt ~/Documents

-$ ls ~/Documents

--rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:23 example.txt

--rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:20 example.txt.~1~

-```

-

-A default backup scheme can be set with the environment variable VERSION_CONTROL. You can set environment variables in your **~/.bashrc** file or dynamically before your command:

-

-

-```

-$ VERSION_CONTROL=numbered mv --backup example.txt ~/Documents

-$ ls ~/Documents

--rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:23 example.txt

--rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:20 example.txt.~1~

--rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:22 example.txt.~2~

-```

-

-The **\--backup** option still respects the **\--interactive** or **-i** option, so it still prompts you to overwrite the destination file, even though it creates a backup before doing so:

-

-

-```

-$ mv --backup=numbered example.txt ~/Documents

-mv: overwrite '~/Documents/example.txt'? y

-$ ls ~/Documents

--rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:24 example.txt

--rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:20 example.txt.~1~

--rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:22 example.txt.~2~

--rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:23 example.txt.~3~

-```

-

-You can override **-i** with the **\--force** or **-f** option.

-

-

-```

-$ mv --backup=numbered --force example.txt ~/Documents

-$ ls ~/Documents

--rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:26 example.txt

--rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:20 example.txt.~1~

--rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:22 example.txt.~2~

--rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:24 example.txt.~3~

--rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:25 example.txt.~4~

-```

-

-The **\--backup** option is not available in BSD **mv**.

-

-#### Moving many files at once

-

-When moving multiple files, **mv** treats the final directory named as the destination:

-

-

-```

-$ mv foo bar baz ~/Documents

-$ ls ~/Documents

-foo bar baz

-```

-

-If the final item is not a directory, **mv** returns an error:

-

-

-```

-$ mv foo bar baz

-mv: target 'baz' is not a directory

-```

-

-The syntax of GNU **mv** is fairly flexible. If you are unable to provide the **mv** command with the destination as the final argument, use the **\--target-directory** or **-t** option:

-

-

-```

-$ mv --target-directory=~/Documents foo bar baz

-$ ls ~/Documents

-foo bar baz

-```

-

-This is especially useful when constructing **mv** commands from the output of some other command, such as the **find** command, **xargs**, or [GNU Parallel][10].

-

-#### Moving based on mtime

-

-With GNU **mv**, you can define a move action based on whether the file being moved is newer than the destination file it would replace. This option is possible with the **\--update** or **-u** option, and is not available in BSD **mv**:

-

-

-```

-$ ls -l ~/Documents

--rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:32 example.txt

-$ ls -l

--rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:42 example.txt

-$ mv --update example.txt ~/Documents

-$ ls -l ~/Documents

--rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:42 example.txt

-$ ls -l

-```

-

-This result is exclusively based on the files’ modification time, not on a diff of the two files, so use it with care. It’s easy to fool **mv** with a mere **touch** command:

-

-

-```

-$ cat example.txt

-one

-$ cat ~/Documents/example.txt

-one

-two

-$ touch example.txt

-$ mv --update example.txt ~/Documents

-$ cat ~/Documents/example.txt

-one

-```

-

-Obviously, this isn’t the most intelligent update function available, but it offers basic protection against overwriting recent data.

-

-### Moving

-

-There are more ways to move data than just the **mv** command, but as the default program for the job, **mv** is a good universal option. Now that you know what options you have available, you can use **mv** smarter than ever before.

-

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-

-via: https://opensource.com/article/19/8/moving-files-linux-depth

-

-作者:[Seth Kenlon][a]

-选题:[lujun9972][b]

-译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

-校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

-

-本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

-

-[a]: https://opensource.com/users/sethhttps://opensource.com/users/doni08521059

-[b]: https://github.com/lujun9972

-[1]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/styles/image-full-size/public/lead-images/files_documents_paper_folder.png?itok=eIJWac15 (Files in a folder)

-[2]: https://opensource.com/article/19/7/master-ls-command

-[3]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/gnome-mv.jpg (Moving a file in GNOME.)

-[4]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/kde-mv.jpg (Moving a file in KDE.)

-[5]: https://opensource.com/article/19/7/understanding-file-paths-and-how-use-them

-[6]: https://opensource.com/article/19/7/navigating-filesystem-relative-paths

-[7]: https://opensource.com/article/19/7/what-posix-richard-stallman-explains

-[8]: https://opensource.com/article/19/7/copying-files-linux

-[9]: https://opensource.com/article/19/7/bash-aliases

-[10]: https://opensource.com/article/18/5/gnu-parallel

diff --git a/sources/tech/20190830 git exercises- navigate a repository.md b/sources/tech/20190830 git exercises- navigate a repository.md

deleted file mode 100644

index bfafd73d66..0000000000

--- a/sources/tech/20190830 git exercises- navigate a repository.md

+++ /dev/null

@@ -1,84 +0,0 @@

-[#]: collector: (lujun9972)

-[#]: translator: ( )

-[#]: reviewer: ( )

-[#]: publisher: ( )

-[#]: url: ( )

-[#]: subject: (git exercises: navigate a repository)

-[#]: via: (https://jvns.ca/blog/2019/08/30/git-exercises--navigate-a-repository/)

-[#]: author: (Julia Evans https://jvns.ca/)

-

-git exercises: navigate a repository

-======

-

-I think the [curl exercises][1] the other day went well, so today I woke up and wanted to try writing some Git exercises. Git is a big thing to learn, probably too big to learn in a few hours, so my first idea for how to break it down was by starting by **navigating** a repository.

-

-I was originally going to use a toy test repository, but then I thought – why not a real repository? That’s way more fun! So we’re going to navigate the repository for the Ruby programming language. You don’t need to know any C to do this exercise, it’s just about getting comfortable with looking at how files in a repository change over time.

-

-### clone the repository

-

-To get started, clone the repository:

-

-```

-git clone https://github.com/ruby/ruby

-```

-

-The big different thing about this repository (as compared to most of the repositories you’ll work with in real life) is that it doesn’t have branches, but it DOES have lots of tags, which are similar to branches in that they’re both just pointers to a commit. So we’ll do exercises with tags instead of branches. The way you _change_ tags and branches are very different, but the way you _look at_ tags and branches is exactly the same.

-

-### a git SHA always refers to the same code

-

-The most important thing to keep in mind while doing these exercises is that a git SHA like `9e3d9a2a009d2a0281802a84e1c5cc1c887edc71` always refers to the same code, as explained in this page. This page is from a zine I wrote with Katie Sylor-Miller called [Oh shit, git!][2]. (She also has a great site called that inspired the zine).

-

-

-

-We’ll be using git SHAs really heavily in the exercises to get you used to working with them and to help understand how they correspond to tags and branches.

-

-### git subcommands we’ll be using

-

-All of these exercises only use 5 git subcommands:

-

-```

-git checkout

-git log (--oneline, --author, and -S will be useful)

-git diff (--stat will be useful)

-git show

-git status

-```

-

-### exercises

-

- 1. Check out matz’s commit of Ruby from 1998. The commit ID is `3db12e8b236ac8f88db8eb4690d10e4a3b8dbcd4`. Find out how many lines of code Ruby was at that time.

- 2. Check out the current master branch

- 3. Look at the history for the file `hash.c`. What was the last commit ID that changed that file?

- 4. Get a diff of how `hash.c` has changed in the last 20ish years: compare that file on the master branch to the file at commit `3db12e8b236ac8f88db8eb4690d10e4a3b8dbcd4`.

- 5. Find a recent commit that changed `hash.c` and look at the diff for that commit

- 6. This repository has a bunch of **tags** for every Ruby release. Get a list of all the tags.

- 7. Find out how many files changed between tag `v1_8_6_187` and tag `v1_8_6_188`

- 8. Find a commit (any commit) from 2015 and check it out, look at the files very briefly, then go back to the master branch.

- 9. Find out what commit the tag `v1_8_6_187` corresponds to.

- 10. List the directory `.git/refs/tags`. Run `cat .git/refs/tags/v1_8_6_187` to see the contents of one of those files.

- 11. Find out what commit ID `HEAD` corresponds to right now.

- 12. Find out how many commits have been made to the `test/` directory

- 13. Get a diff of `lib/telnet.rb` between the commits `65a5162550f58047974793cdc8067a970b2435c0` and `9e3d9a2a009d2a0281802a84e1c5cc1c887edc71`. How many lines of that file were changed?

- 14. How many commits were made between Ruby 2.5.1 and 2.5.2 (tags `v2_5_1` and `v2_5_3`) (this one is a tiny bit tricky, there’s more than one step)

- 15. How many commits were authored by `matz` (Ruby’s creator)?

- 16. What’s the most recent commit that included the word `tkutil`?

- 17. Check out the commit `e51dca2596db9567bd4d698b18b4d300575d3881` and create a new branch that points at that commit.

- 18. Run `git reflog` to see all the navigating of the repository you’ve done so far

-

-

-

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-

-via: https://jvns.ca/blog/2019/08/30/git-exercises--navigate-a-repository/

-

-作者:[Julia Evans][a]

-选题:[lujun9972][b]

-译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

-校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

-

-本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

-

-[a]: https://jvns.ca/

-[b]: https://github.com/lujun9972

-[1]: https://jvns.ca/blog/2019/08/27/curl-exercises/

-[2]: https://wizardzines.com/zines/oh-shit-git/

diff --git a/sources/tech/20190909 How to Setup Multi Node Elastic Stack Cluster on RHEL 8 - CentOS 8.md b/sources/tech/20190909 How to Setup Multi Node Elastic Stack Cluster on RHEL 8 - CentOS 8.md

index f56e708426..bef51b5a9f 100644

--- a/sources/tech/20190909 How to Setup Multi Node Elastic Stack Cluster on RHEL 8 - CentOS 8.md

+++ b/sources/tech/20190909 How to Setup Multi Node Elastic Stack Cluster on RHEL 8 - CentOS 8.md

@@ -1,5 +1,5 @@

[#]: collector: (lujun9972)

-[#]: translator: ( )

+[#]: translator: (heguangzhi)

[#]: reviewer: ( )

[#]: publisher: ( )

[#]: url: ( )

@@ -457,7 +457,7 @@ via: https://www.linuxtechi.com/setup-multinode-elastic-stack-cluster-rhel8-cent

作者:[Pradeep Kumar][a]

选题:[lujun9972][b]

-译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

+译者:[heguangzhi](https://github.com/heguangzhi)

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

diff --git a/sources/tech/20190918 How to remove carriage returns from text files on Linux.md b/sources/tech/20190918 How to remove carriage returns from text files on Linux.md

deleted file mode 100644

index 45b8a8b89d..0000000000

--- a/sources/tech/20190918 How to remove carriage returns from text files on Linux.md

+++ /dev/null

@@ -1,114 +0,0 @@

-[#]: collector: (lujun9972)

-[#]: translator: (geekpi)

-[#]: reviewer: ( )

-[#]: publisher: ( )

-[#]: url: ( )

-[#]: subject: (How to remove carriage returns from text files on Linux)

-[#]: via: (https://www.networkworld.com/article/3438857/how-to-remove-carriage-returns-from-text-files-on-linux.html)

-[#]: author: (Sandra Henry-Stocker https://www.networkworld.com/author/Sandra-Henry_Stocker/)

-

-How to remove carriage returns from text files on Linux

-======

-When carriage returns (also referred to as Ctrl+M's) get on your nerves, don't fret. There are several easy ways to show them the door.

-[Kim Siever][1]

-

-Carriage returns go back a long way – as far back as typewriters on which a mechanism or a lever swung the carriage that held a sheet of paper to the right so that suddenly letters were being typed on the left again. They have persevered in text files on Windows, but were never used on Linux systems. This incompatibility sometimes causes problems when you’re trying to process files on Linux that were created on Windows, but it's an issue that is very easily resolved.

-

-The carriage return, also referred to as **Ctrl+M**, character would show up as an octal 15 if you were looking at the file with an **od** octal dump) command. The characters **CRLF** are often used to represent the carriage return and linefeed sequence that ends lines on Windows text files. Those who like to gaze at octal dumps will spot the **\r \n**. Linux text files, by comparison, end with just linefeeds.

-

-**[ Two-Minute Linux Tips: [Learn how to master a host of Linux commands in these 2-minute video tutorials][2] ]**

-

-Here's a sample of **od** output with the lines containing the **CRLF** characters in both octal and character form highlighted.

-

-```

-$ od -bc testfile.txt

-0000000 124 150 151 163 040 151 163 040 141 040 164 145 163 164 040 146

- T h i s i s a t e s t f

-0000020 151 154 145 040 146 162 157 155 040 127 151 156 144 157 167 163

- i l e f r o m W i n d o w s

-0000040 056 015 012 111 164 047 163 040 144 151 146 146 145 162 145 156 <==

- . \r \n I t ' s d i f f e r e n <==

-0000060 164 040 164 150 141 156 040 141 040 125 156 151 170 040 164 145

- t t h a n a U n i x t e

-0000100 170 164 040 146 151 154 145 015 012 167 157 165 154 144 040 142 <==

- x t f i l e \r \n w o u l d b <==

-```

-

-While these characters don’t represent a huge problem, they can sometimes interfere when you want to parse the text files in some way and don’t want to have to code around their presence or absence.

-

-### 3 ways to remove carriage return characters from text files

-

-Fortunately, there are several ways to easily remove carriage return characters. Here are three options:

-

-#### dos2unix

-

-You might need to go through the trouble of installing it, but **dos2unix** is probably the easiest way to turn Windows text files into Unix/Linux text files. One command with one argument, and you’re done. No second file name is required. The file will be changed in place.

-

-```

-$ dos2unix testfile.txt

-dos2unix: converting file testfile.txt to Unix format...

-```

-

-You should see the file length decrease, depending on how many lines it contains. A file with 100 lines would likely shrink by 99 characters, since only the last line will not end with the **CRLF** characters.

-

-Before:

-

-```

--rw-rw-r-- 1 shs shs 121 Sep 14 19:11 testfile.txt

-```

-

-After:

-

-```

--rw-rw-r-- 1 shs shs 118 Sep 14 19:12 testfile.txt

-```

-

-If you need to convert a large collection of files, don't fix them one at a time. Instead, put them all in a directory by themselves and run a command like this:

-

-```

-$ find . -type f -exec dos2unix {} \;

-```

-

-In this command, we use find to locate regular files and then run the **dos2unix** command to convert them one at a time. The {} in the command is replaced by the filename. You should be sitting in the directory with the files when you run it. This command could damage other types of files, such as those that contain octal 15 characters in some context other than a text file (e.g., bytes in an image file).

-

-#### sed

-

-You can also use **sed**, the stream editor, to remove carriage returns. You will, however, have to supply a second file name. Here’s an example:

-

-```

-$ sed -e “s/^M//” before.txt > after.txt

-```

-

-One important thing to note is that you DON’T type what that command appears to be. You must enter **^M** by typing **Ctrl+V** followed by **Ctrl+M**. The “s” is the substitute command. The slashes separate the text we’re looking for (the Ctrl+M) and the text (nothing in this case) that we’re replacing it with.

-

-#### vi

-

-You can even remove carriage return (**Ctrl+M**) characters with **vi**, although this assumes you’re not running through hundreds of files and are maybe making some other changes, as well. You would type “**:**” to go to the command line and then type the string shown below. As with **sed**, the **^M** portion of this command requires typing **Ctrl+V** to get the **^** and then **Ctrl+M** to insert the **M**. The **%s** is a substitute operation, the slashes again separate the characters we want to remove and the text (nothing) we want to replace it with. The “**g**” (global) means to do this on every line in the file.

-

-```

-:%s/^M//g

-```

-

-#### Wrap-up

-

-The **dos2unix** command is probably the easiest to remember and most reliable way to remove carriage returns from text files. Other options are a little trickier to use, but they provide the same basic function.

-

-Join the Network World communities on [Facebook][3] and [LinkedIn][4] to comment on topics that are top of mind.

-

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-

-via: https://www.networkworld.com/article/3438857/how-to-remove-carriage-returns-from-text-files-on-linux.html

-

-作者:[Sandra Henry-Stocker][a]

-选题:[lujun9972][b]

-译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

-校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

-

-本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

-

-[a]: https://www.networkworld.com/author/Sandra-Henry_Stocker/

-[b]: https://github.com/lujun9972

-[1]: https://www.flickr.com/photos/kmsiever/5895380540/in/photolist-9YXnf5-cNmpxq-2KEvib-rfecPZ-9snnkJ-2KAcDR-dTxzKW-6WdgaG-6H5i46-2KzTZX-7cnSw7-e3bUdi-a9meh9-Zm3pD-xiFhs-9Hz6YM-ar4DEx-4PXAhw-9wR4jC-cihLcs-asRFJc-9ueXvG-aoWwHq-atwL3T-ai89xS-dgnntH-5en8Te-dMUDd9-aSQVn-dyZqij-cg4SeS-abygkg-f2umXt-Xk129E-4YAeNn-abB6Hb-9313Wk-f9Tot-92Yfva-2KA7Sv-awSCtG-2KDPzb-eoPN6w-FE9oi-5VhaNf-eoQgx7-eoQogA-9ZWoYU-7dTGdG-5B1aSS

-[2]: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL7D2RMSmRO9J8OTpjFECi8DJiTQdd4hua

-[3]: https://www.facebook.com/NetworkWorld/

-[4]: https://www.linkedin.com/company/network-world

diff --git a/sources/tech/20190920 Hone advanced Bash skills by building Minesweeper.md b/sources/tech/20190920 Hone advanced Bash skills by building Minesweeper.md

index 4ef4ba10bf..1a6a4a255c 100644

--- a/sources/tech/20190920 Hone advanced Bash skills by building Minesweeper.md

+++ b/sources/tech/20190920 Hone advanced Bash skills by building Minesweeper.md

@@ -1,5 +1,5 @@

[#]: collector: (lujun9972)

-[#]: translator: ( )

+[#]: translator: (wenwensnow)

[#]: reviewer: ( )

[#]: publisher: ( )

[#]: url: ( )

@@ -28,7 +28,6 @@ Before I started writing any code, I outlined the ingredients I needed to create

5. Create the endgame logic

-

### Print a minefield

In Minesweeper, the game world is a 2D array (columns and rows) of concealed cells. Each cell may or may not contain an explosive mine. The player's objective is to reveal cells that contain no mine, and to never reveal a mine. Bash version of the game uses a 10x10 matrix, implemented using simple bash arrays.

diff --git a/translated/tech/20190822 How to move a file in Linux.md b/translated/tech/20190822 How to move a file in Linux.md

new file mode 100644

index 0000000000..2a2215b52d

--- /dev/null

+++ b/translated/tech/20190822 How to move a file in Linux.md

@@ -0,0 +1,269 @@

+[#]: collector: (lujun9972)

+[#]: translator: (wxy)

+[#]: reviewer: (wxy)

+[#]: publisher: ( )

+[#]: url: ( )

+[#]: subject: (How to move a file in Linux)

+[#]: via: (https://opensource.com/article/19/8/moving-files-linux-depth)

+[#]: author: (Seth Kenlon https://opensource.com/users/sethhttps://opensource.com/users/doni08521059)

+

+在 Linux 中如何移动文件

+======

+

+> 无论你是刚接触 Linux 的文件移动的新手还是已有丰富的经验,你都可以通过此深入的文章中学到一些东西。

+

+

+

+在 Linux 中移动文件看似比较简单,但是可用的选项却比大多数人想象的要多。本文介绍了初学者如何在 GUI 和命令行中移动文件,还介绍了底层实际上发生了什么,并介绍了许多有一定经验的用户也很少使用的命令行选项。

+

+### 移动什么?

+

+在研究移动文件之前,有必要仔细研究*移动*文件系统对象时实际发生的情况。当文件创建后,会将其分配给一个索引节点,这是文件系统中用于数据存储的固定点。你可以使用 [ls][2] 命令看到文件对应的索引节点:

+

+```

+$ ls --inode example.txt

+7344977 example.txt

+```

+

+移动文件时,实际上并没有将数据从一个索引节点移动到另一个索引节点,只是给文件对象分配了新的名称或文件路径而已。实际上,文件在移动时会保留其权限,因为移动文件不会更改或重新创建文件。(LCTT 译注:在不跨卷、分区和存储器时,移动文件是不会重新创建文件的;反之亦然)

+

+文件和目录的索引节点并没有暗示这种继承关系,而是由文件系统本身决定的。索引节点的分配是基于文件创建时的顺序分配的,并且完全独立于你组织计算机文件的方式。一个目录“内”的文件的索引节点号可能比其父目录的索引节点号更低或更高。例如:

+

+```

+$ mkdir foo

+$ mv example.txt foo

+$ ls --inode

+7476865 foo

+$ ls --inode foo

+7344977 example.txt

+```

+

+但是,将文件从一个硬盘驱动器移动到另一个硬盘驱动器时,索引节点基本上会更改。发生这种情况是因为必须将新数据写入新文件系统。因此,在 Linux 中,移动和重命名文件的操作实际上是相同的操作。无论你将文件移动到另一个目录还是在同一目录使用新名称,这两个操作均由同一个底层程序执行。

+

+本文重点介绍将文件从一个目录移动到另一个目录。

+

+### 用鼠标移动文件

+

+图形用户界面是大多数人都熟悉的友好的抽象层,位于复杂的二进制数据集合之上。这也是在 Linux 桌面上移动文件的首选方法,也是最直观的方法。从一般意义上来说,如果你习惯使用台式机,那么你可能已经知道如何在硬盘驱动器上移动文件。例如,在 GNOME 桌面上,将文件从一个窗口拖放到另一个窗口时的默认操作是移动文件而不是复制文件,因此这可能是该桌面上最直观的操作之一:

+

+![Moving a file in GNOME.][3]

+

+而 KDE Plasma 桌面中的 Dolphin 文件管理器默认情况下会提示用户以执行不同的操作。拖动文件时按住 `Shift` 键可强制执行移动操作:

+

+![Moving a file in KDE.][4]

+

+### 在命令行移动文件

+

+用于在 Linux、BSD、Illumos、Solaris 和 MacOS 上移动文件的 shell 命令是 `mv`。不言自明,简单的命令 `mv ` 会将源文件移动到指定的目标,源和目标都由[绝对][5]或[相对][6]文件路径定义。如前所述,`mv` 是 [POSIX][7] 用户的常用命令,其有很多不为人知的附加选项,因此,无论你是新手还是有经验的人,本文都会为你带来一些有用的选项。

+

+但是,不是所有 `mv` 命令都是由同一个人编写的,因此取决于你的操作系统,你可能拥有 GNU `mv`、BSD `mv` 或 Sun `mv`。命令的选项因其实现而异(BSD `mv` 根本没有长选项),因此请参阅你的 `mv` 手册页以查看支持的内容,或安装你的首选版本(这是开源的奢侈之处)。

+

+#### 移动文件

+

+要使用 `mv` 将文件从一个文件夹移动到另一个文件夹,请记住语法 `mv `。 例如,要将文件 `example.txt` 移到你的 `Documents` 目录中:

+

+```

+$ touch example.txt

+$ mv example.txt ~/Documents

+$ ls ~/Documents

+example.txt

+```

+

+就像你通过将文件拖放到文件夹图标上来移动文件一样,此命令不会将 `Documents` 替换为 `example.txt`。相反,`mv` 会检测到 `Documents` 是一个文件夹,并将 `example.txt` 文件放入其中。

+

+你还可以方便地在移动文件时重命名该文件:

+

+```

+$ touch example.txt

+$ mv example.txt ~/Documents/foo.txt

+$ ls ~/Documents

+foo.txt

+```

+

+这很重要,这使你不用将文件移动到另一个位置,也可以重命名文件,例如:

+

+```

+$ touch example.txt

+$ mv example.txt foo2.txt

+$ ls foo2.txt`

+```

+

+#### 移动目录

+

+不像 [cp][8] 命令,`mv` 命令处理文件和目录没有什么不同,你可以用同样的格式移动目录或文件:

+

+```

+$ touch file.txt

+$ mkdir foo_directory

+$ mv file.txt foo_directory

+$ mv foo_directory ~/Documents

+```

+

+#### 安全地移动文件

+

+如果你移动一个文件到一个已有同名文件的地方,默认情况下,`mv` 会用你移动的文件替换目标文件。这种行为被称为清除,有时候这就是你想要的结果,而有时则不是。

+

+一些发行版将 `mv` 别名定义为 `mv --interactive`(你也可以[自己写一个][9]),这会提醒你确认是否覆盖。而另外一些发行版没有这样做,那么你可以使用 `--interactive` 或 `-i` 选项来确保当两个文件有一样的名字而发生冲突时让 `mv` 请你来确认。

+

+```

+$ mv --interactive example.txt ~/Documents

+mv: overwrite '~/Documents/example.txt'?

+```

+

+如果你不想手动干预,那么可以使用 `--no-clobber` 或 `-n`。该选项会在发生冲突时静默拒绝移动操作。在这个例子当中,一个名为 `example.txt` 的文件以及存在于 `~/Documents`,所以它不会如命令要求从当前目录移走。

+

+```

+$ mv --no-clobber example.txt ~/Documents

+$ ls

+example.txt

+```

+

+#### 带备份的移动

+

+如果你使用 GNU `mv`,有一个备份选项提供了另外一种安全移动的方式。要为任何冲突的目标文件创建备份文件,可以使用 `-b` 选项。

+

+```

+$ mv -b example.txt ~/Documents

+$ ls ~/Documents

+example.txt example.txt~

+```

+

+这个选项可以确保 `mv` 完成移动操作,但是也会保护目录位置的已有文件。

+

+另外的 GNU 备份选项是 `--backup`,它带有一个定义了备份文件如何命名的参数。

+

+* `existing`:如果在目标位置已经存在了编号备份文件,那么会创建编号备份。否则,会使用 `simple` 方式。

+* `none`:即使设置了 `--backup`,也不会创建备份。当 `mv` 被别名定义为带有备份选项时,这个选项可以覆盖这种行为。

+* `numbered`:给目标文件名附加一个编号。

+* `simple`:给目标文件附加一个 `~`,当你日常使用带有 `--ignore-backups` 选项的 [ls][2] 时,这些文件可以很方便地隐藏起来。

+

+简单来说:

+

+```

+$ mv --backup=numbered example.txt ~/Documents

+$ ls ~/Documents

+-rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:23 example.txt

+-rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:20 example.txt.~1~

+```

+

+可以使用环境变量 `VERSION_CONTROL` 设置默认的备份方案。你可以在 `~/.bashrc` 文件中设置该环境变量,也可以在命令前动态设置:

+

+```

+$ VERSION_CONTROL=numbered mv --backup example.txt ~/Documents

+$ ls ~/Documents

+-rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:23 example.txt

+-rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:20 example.txt.~1~

+-rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:22 example.txt.~2~

+```

+

+`--backup` 选项仍然遵循 `--interactive` 或 `-i` 选项,因此即使它在执行备份之前创建了备份,它仍会提示你覆盖目标文件:

+

+```

+$ mv --backup=numbered example.txt ~/Documents

+mv: overwrite '~/Documents/example.txt'? y

+$ ls ~/Documents

+-rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:24 example.txt

+-rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:20 example.txt.~1~

+-rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:22 example.txt.~2~

+-rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:23 example.txt.~3~

+```

+

+你可以使用 `--force` 或 `-f` 选项覆盖 `-i`。

+

+```

+$ mv --backup=numbered --force example.txt ~/Documents

+$ ls ~/Documents

+-rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:26 example.txt

+-rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:20 example.txt.~1~

+-rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:22 example.txt.~2~

+-rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:24 example.txt.~3~

+-rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:25 example.txt.~4~

+```

+

+`--backup` 选项在 BSD `mv` 中不可用。

+

+#### 一次性移动多个文件

+

+移动多个文件时,`mv` 会将最终目录视为目标:

+

+```

+$ mv foo bar baz ~/Documents

+$ ls ~/Documents

+foo bar baz

+```

+

+如果最后一个项目不是目录,则 `mv` 返回错误:

+

+```

+$ mv foo bar baz

+mv: target 'baz' is not a directory

+```

+

+GNU `mv` 的语法相当灵活。如果无法把目标目录作为提供给 `mv` 命令的最终参数,请使用 `--target-directory` 或 `-t` 选项:

+

+```

+$ mv --target-directory=~/Documents foo bar baz

+$ ls ~/Documents

+foo bar baz

+```

+

+当从某些其他命令的输出构造 `mv` 命令时(例如 `find` 命令、`xargs` 或 [GNU Parallel][10]),这特别有用。

+

+#### 基于修改时间移动

+

+使用 GNU `mv`,你可以根据要移动的文件是否比要替换的目标文件新来定义移动动作。该方式可以通过 `--update` 或 `-u` 选项使用,在BSD `mv` 中不可用:

+

+```

+$ ls -l ~/Documents

+-rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:32 example.txt

+$ ls -l

+-rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:42 example.txt

+$ mv --update example.txt ~/Documents

+$ ls -l ~/Documents

+-rw-rw-r--. 1 seth users 128 Aug 1 17:42 example.txt

+$ ls -l

+```

+

+此结果仅基于文件的修改时间,而不是两个文件的差异,因此请谨慎使用。只需使用 `touch` 命令即可愚弄 `mv`:

+

+```

+$ cat example.txt

+one

+$ cat ~/Documents/example.txt

+one

+two

+$ touch example.txt

+$ mv --update example.txt ~/Documents

+$ cat ~/Documents/example.txt

+one

+```

+

+显然,这不是最智能的更新功能,但是它提供了防止覆盖最新数据的基本保护。

+

+### 移动

+

+除了 `mv` 命令以外,还有更多的移动数据的方法,但是作为这项任务的默认程序,`mv` 是一个很好的通用选择。现在你知道了有哪些可以使用的选项,可以比以前更智能地使用 `mv` 了。

+

+--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

+

+via: https://opensource.com/article/19/8/moving-files-linux-depth

+

+作者:[Seth Kenlon][a]

+选题:[lujun9972][b]

+译者:[wxy](https://github.com/wxy)

+校对:[wxy](https://github.com/wxy)

+

+本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

+

+[a]: https://opensource.com/users/sethhttps://opensource.com/users/doni08521059

+[b]: https://github.com/lujun9972

+[1]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/styles/image-full-size/public/lead-images/files_documents_paper_folder.png?itok=eIJWac15 (Files in a folder)

+[2]: https://opensource.com/article/19/7/master-ls-command

+[3]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/gnome-mv.jpg (Moving a file in GNOME.)

+[4]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/kde-mv.jpg (Moving a file in KDE.)

+[5]: https://opensource.com/article/19/7/understanding-file-paths-and-how-use-them

+[6]: https://opensource.com/article/19/7/navigating-filesystem-relative-paths

+[7]: https://opensource.com/article/19/7/what-posix-richard-stallman-explains

+[8]: https://opensource.com/article/19/7/copying-files-linux

+[9]: https://opensource.com/article/19/7/bash-aliases

+[10]: https://opensource.com/article/18/5/gnu-parallel

diff --git a/sources/tech/20190901 Different Ways to Configure Static IP Address in RHEL 8.md b/translated/tech/20190901 Different Ways to Configure Static IP Address in RHEL 8.md

similarity index 52%

rename from sources/tech/20190901 Different Ways to Configure Static IP Address in RHEL 8.md

rename to translated/tech/20190901 Different Ways to Configure Static IP Address in RHEL 8.md

index 9c354e84e1..ad0f8822a0 100644

--- a/sources/tech/20190901 Different Ways to Configure Static IP Address in RHEL 8.md

+++ b/translated/tech/20190901 Different Ways to Configure Static IP Address in RHEL 8.md

@@ -7,26 +7,26 @@

[#]: via: (https://www.linuxtechi.com/configure-static-ip-address-rhel8/)

[#]: author: (Pradeep Kumar https://www.linuxtechi.com/author/pradeep/)

-Different Ways to Configure Static IP Address in RHEL 8

-======

+在 RHEL8 配置静态 IP 地址的不同方法

+

+======

+在 **Linux服务器** 上工作时,在网卡/以太网卡上分配静态 IP 地址是每个 Linux 工程师的常见任务之一。如果一个人在Linux 服务器上正确配置了静态地址,那么他/她就可以通过网络远程访问它。在本文中,我们将演示在 RHEL 8 服务器网卡上配置静态 IP 地址的不同方法。

-While Working on **Linux Servers**, assigning Static IP address on NIC / Ethernet cards is one of the common tasks that every Linux engineer do. If one configures the **Static IP address** correctly on a Linux server then he/she can access it remotely over network. In this article we will demonstrate what are different ways to assign Static IP address on RHEL 8 Server’s NIC.

[![Configure-Static-IP-RHEL8][1]][2]

-Following are the ways to configure Static IP on a NIC,

-

- * nmcli (command line tool)

- * Network Scripts files(ifcfg-*)

- * nmtui (text based user interface)

+以下是在网卡上配置静态IP的方法:

+

+ * nmcli (命令行工具)

+ * 网络脚本文件(ifcfg-*)

+ * nmtui (基于文本的用户界面)

+### 使用 nmcli 命令行工具配置静态 IP 地址

-### Configure Static IP Address using nmcli command line tool

+每当我们安装 RHEL 8 服务器时,就会自动安装命令行工具 ‘**nmcli**’ ,网络管理器使用 nmcli,并允许我们在以太网卡上配置静态 IP 地址。

-Whenever we install RHEL 8 server then ‘**nmcli**’, a command line tool is installed automatically, nmcli is used by network manager and allows us to configure static ip address on Ethernet cards.

-

-Run the below ip addr command to list Ethernet cards on your RHEL 8 server

+运行下面的 ip addr 命令,列出 RHEL 8 服务器上的以太网卡

```

[root@linuxtechi ~]# ip addr

@@ -34,9 +34,10 @@ Run the below ip addr command to list Ethernet cards on your RHEL 8 server

![ip-addr-command-rhel8][1]

-As we can see in above command output, we have two NICs enp0s3 & enp0s8. Currently ip address assigned to the NIC is via dhcp server.

-Let’s assume we want to assign the static IP address on first NIC (enp0s3) with the following details,

+正如我们在上面的命令输出中看到的,我们有两个网卡 enp0s3 & ampenp0s8。当前分配给网卡的 IP 地址是通过 DHCP 服务器获得的 。

+

+假设我们希望在第一个网卡 (enp0s3) 上分配静态IP地址,具体内容如下:

* IP address = 192.168.1.4

* Netmask = 255.255.255.0

@@ -44,10 +45,9 @@ Let’s assume we want to assign the static IP address on first NIC (enp0s3) wit

* DNS = 8.8.8.8

+依次运行以下 nmcli 命令来配置静态 IP,

-Run the following nmcli commands one after the another to configure static ip,

-

-List currently active Ethernet cards using “**nmcli connection**” command,

+使用“**nmcli connection **”命令列出当前活动的以太网卡,

```

[root@linuxtechi ~]# nmcli connection

@@ -56,44 +56,46 @@ enp0s3 7c1b8444-cb65-440d-9bf6-ea0ad5e60bae ethernet enp0s3

virbr0 3020c41f-6b21-4d80-a1a6-7c1bd5867e6c bridge virbr0

[root@linuxtechi ~]#

```

+在 nmcli 命令下使用,在 enp0s3 上分配静态 IP。

-Use beneath nmcli command to assign static ip on enp0s3,

-**Syntax:**

-# nmcli connection modify <interface_name> ipv4.address <ip/prefix>

+**句法:**

-**Note:** In short form, we usually replace connection with ‘con’ keyword and modify with ‘mod’ keyword in nmcli command.

+nmcli connection modify <interface_name> ipv4.address <ip/prefix>

-Assign ipv4 (192.168.1.4) to enp0s3 interface,

+

+**注意:** 简化语句,在 nmcli 命令中,我们通常用 “con” 关键字替换连接,并用 “mod”关 键字进行修改。

+

+将 ipv4 (192.168.1.4) 分配给 enp0s3 网卡上。

```

[root@linuxtechi ~]# nmcli con mod enp0s3 ipv4.addresses 192.168.1.4/24

[root@linuxtechi ~]#

```

-Set the gateway using below nmcli command,

+使用下面的 nmcli 命令设置网关,

```

[root@linuxtechi ~]# nmcli con mod enp0s3 ipv4.gateway 192.168.1.1

[root@linuxtechi ~]#

```

-Set the manual configuration (from dhcp to static),

+设置手动配置(从dhcp到static),

```

[root@linuxtechi ~]# nmcli con mod enp0s3 ipv4.method manual

[root@linuxtechi ~]#

```

-Set DNS value as “8.8.8.8”,

+设置 DNS 值为 “8.8.8.8”,

```

[root@linuxtechi ~]# nmcli con mod enp0s3 ipv4.dns "8.8.8.8"

[root@linuxtechi ~]#

```

-To save the above changes and to reload the interface execute the beneath nmcli command,

+要保存上述更改并重新加载,请执行 nmcli 如下命令,

```

[root@linuxtechi ~]# nmcli con up enp0s3

@@ -101,7 +103,7 @@ Connection successfully activated (D-Bus active path: /org/freedesktop/NetworkMa

[root@linuxtechi ~]#

```

-Above command output confirms that interface enp0s3 has been configured successfully.Whatever the changes we have made using above nmcli commands, those changes is saved permanently under the file “etc/sysconfig/network-scripts/ifcfg-enp0s3”

+以上命令显示网卡 enp0s3 已成功配置。 我们使用 nmcli 命令进行了那些更改都将永久保存在文件“etc/sysconfig/network-scripts/ifcfg-enp0s3” 里。

```

[root@linuxtechi ~]# cat /etc/sysconfig/network-scripts/ifcfg-enp0s3

@@ -109,15 +111,16 @@ Above command output confirms that interface enp0s3 has been configured successf

![ifcfg-enp0s3-file-rhel8][1]

-To Confirm whether IP address has been to enp0s3 interface use the below ip command,

+要确认 IP 地址是否分配给了 enp0s3 网卡了,请使用以下 IP 命令查看,

+

```

[root@linuxtechi ~]#ip addr show enp0s3

```

-### Configure Static IP Address manually using network-scripts (ifcfg-) files

+### 使用网络脚本文件(ifcfg-)手动配置静态 IP 地址

-We can configure the static ip address to an ethernet card using its network-script or ‘ifcfg-‘ files. Let’s assume we want to assign the static ip address on our second Ethernet card ‘enp0s8’.

+我们可以使用配置以太网卡的网络脚本或“ifcfg-”文件来配置以太网卡的静态 IP 地址。假设我们想在第二个以太网卡 “enp0s8” 上分配静态IP 地址:

* IP= 192.168.1.91

* Netmask / Prefix = 24

@@ -125,8 +128,7 @@ We can configure the static ip address to an ethernet card using its network-scr

* DNS1=4.2.2.2

-

-Go to the directory “/etc/sysconfig/network-scripts” and look for the file ‘ifcfg- enp0s8’, if it does not exist then create it with following content,

+转到目录 "/etc/sysconfig/network-scripts ",查找文件 'ifcfg- enp0s8',如果它不存在,则使用以下内容创建它,

```

[root@linuxtechi ~]# cd /etc/sysconfig/network-scripts/

@@ -142,14 +144,16 @@ GATEWAY="192.168.1.1"

DNS1="4.2.2.2"

```

-Save and exit the file and then restart network manager service to make above changes into effect,

+

+保存并退出文件,然后重新启动网络管理器服务以使上述更改生效,

```

[root@linuxtechi network-scripts]# systemctl restart NetworkManager

[root@linuxtechi network-scripts]#

```

-Now use below ip command to verify whether ip address is assigned to nic or not,

+现在使用下面的 IP 命令来验证 IP 地址是否分配给网卡,

+

```

[root@linuxtechi ~]# ip add show enp0s8

@@ -162,13 +166,14 @@ Now use below ip command to verify whether ip address is assigned to nic or not,

[root@linuxtechi ~]#

```

-Above output confirms that static ip address has been configured successfully on the NIC ‘enp0s8’

-### Configure Static IP Address using ‘nmtui’ utility

+以上输出内容确认静态 IP 地址已在网卡“enp0s8”上成功配置了

-nmtui is a text based user interface for controlling network manager, when we execute nmtui, it will open a text base user interface through which we can add, modify and delete connections. Apart from this nmtui can also be used to set hostname of your system.

+### 使用 “nmtui” 实用程序配置静态 IP 地址

-Let’s assume we want to assign static ip address to interface enp0s3 with following details,

+nmtui 是一个基于文本用户界面的,用于控制网络的管理器,当我们执行 nmtui 时,它将打开一个基于文本的用户界面,通过它我们可以添加、修改和删除连接。除此之外,nmtui 还可以用来设置系统的主机名。

+

+假设我们希望通过以下细节将静态 IP 地址分配给网卡 enp0s3 ,

* IP address = 10.20.0.72

* Prefix = 24

@@ -176,8 +181,7 @@ Let’s assume we want to assign static ip address to interface enp0s3 with foll

* DNS1=4.2.2.2

-

-Run nmtui and follow the screen instructions, example is show

+运行 nmtui 并按照屏幕说明操作,示例如下所示

```

[root@linuxtechi ~]# nmtui

@@ -185,31 +189,33 @@ Run nmtui and follow the screen instructions, example is show

[![nmtui-rhel8][1]][3]

-Select the first option ‘**Edit a connection**‘ and then choose the interface as ‘enp0s3’

+

+选择第一个选项 “**Edit a connection**”,然后选择接口为“enp0s3”

[![Choose-interface-nmtui-rhel8][1]][4]

-Choose Edit and then specify the IP address, Prefix, Gateway and DNS Server ip,

+选择编辑,然后指定 IP 地址、前缀、网关和域名系统服务器IP,

[![set-ip-nmtui-rhel8][1]][5]

-Choose OK and hit enter. In the next window Choose ‘**Activate a connection**’

+选择确定,然后点击回车。在下一个窗口中,选择 “**Activate a connection**”

+

[![Activate-option-nmtui-rhel8][1]][6]

-Select **enp0s3**, Choose **Deactivate** & hit enter

+选择 **enp0s3**,选择 **Deactivate** & 点击回车

[![Deactivate-interface-nmtui-rhel8][1]][7]

-Now choose **Activate** & hit enter,

+现在选择 **Activate** &点击回车,

[![Activate-interface-nmtui-rhel8][1]][8]

-Select Back and then select Quit,

+选择“上一步”,然后选择“退出”,

[![Quit-Option-nmtui-rhel8][1]][9]

-Use below IP command to verify whether ip address has been assigned to interface enp0s3

+使用下面的 IP 命令验证 IP 地址是否已分配给接口 enp0s3

```

[root@linuxtechi ~]# ip add show enp0s3

@@ -222,9 +228,10 @@ Use below IP command to verify whether ip address has been assigned to interface

[root@linuxtechi ~]#

```

-Above output confirms that we have successfully assign the static IP address to interface enp0s3 using nmtui utility.

-That’s all from this tutorial, we have covered three different ways to configure ipv4 address to an Ethernet card on RHEL 8 system. Please do not hesitate to share feedback and comments in comments section below.

+以上输出内容显示我们已经使用 nmtui 实用程序成功地将静态 IP 地址分配给接口 enp0s3。

+

+以上就是本教程的全部内容,我们已经介绍了在 RHEL 8 系统上为以太网卡配置 ipv4 地址的三种不同方法。请不要犹豫,在下面的评论部分分享反馈和评论。

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

diff --git a/translated/tech/20190918 How to remove carriage returns from text files on Linux.md b/translated/tech/20190918 How to remove carriage returns from text files on Linux.md

new file mode 100644

index 0000000000..e4ad936b53

--- /dev/null

+++ b/translated/tech/20190918 How to remove carriage returns from text files on Linux.md

@@ -0,0 +1,111 @@

+[#]: collector: (lujun9972)

+[#]: translator: (geekpi)

+[#]: reviewer: ( )

+[#]: publisher: ( )

+[#]: url: ( )

+[#]: subject: (How to remove carriage returns from text files on Linux)

+[#]: via: (https://www.networkworld.com/article/3438857/how-to-remove-carriage-returns-from-text-files-on-linux.html)

+[#]: author: (Sandra Henry-Stocker https://www.networkworld.com/author/Sandra-Henry_Stocker/)

+

+何在 Linux 中删除文本中的回车

+======

+当回车(也称为 Ctrl+M)让你紧张时,别担心。有几种简单的方法消除它们。

+[Kim Siever][1]

+

+回车可以往回追溯很长一段时间 - 早在打字机上就有一个机械装置或杠杆将承载纸滚筒的机架移到最后边,以便重新在左侧输入字母。他们在 Windows 的文本上保留了它,但从未在 Linux 系统上使用过。当你尝试在 Linux 上处理在 Windows 上创建的文件时,这种不兼容性有时会导致问题,但这是一个非常容易解决的问题。

+

+如果你使用 **od**(octal dump)命令查看文件,那么回车(也称为 **Ctrl+M**)字符将显示为八进制的 15。字符 **CRLF** 通常用于表示在 Windows 文本上结束行的回车符和换行符序列。那些注意看八进制转储的会看到 **\r \n**。相比之下,Linux 文本仅以换行符结束。

+

+这有一个 **od** 输出的示例,高亮显示了行中的 **CRLF** 字符,以及它的八进制。

+

+```

+$ od -bc testfile.txt

+0000000 124 150 151 163 040 151 163 040 141 040 164 145 163 164 040 146

+ T h i s i s a t e s t f

+0000020 151 154 145 040 146 162 157 155 040 127 151 156 144 157 167 163

+ i l e f r o m W i n d o w s

+0000040 056 015 012 111 164 047 163 040 144 151 146 146 145 162 145 156 <==

+ . \r \n I t ' s d i f f e r e n <==

+0000060 164 040 164 150 141 156 040 141 040 125 156 151 170 040 164 145

+ t t h a n a U n i x t e

+0000100 170 164 040 146 151 154 145 015 012 167 157 165 154 144 040 142 <==

+ x t f i l e \r \n w o u l d b <==

+```

+

+虽然这些字符不是大问题,但是当你想要以某种方式解析文本,并且不希望就它们是否存在进行编码时,这有时候会产生干扰。

+

+### 3 种从文本中删除回车符的方法

+

+幸运的是,有几种方法可以轻松删除回车符。这有三个选择:

+

+#### dos2unix

+

+你可能会在安装上遇到麻烦,但 **dos2unix** 可能是将 Windows 文本转换为 Unix/Linux 文本的最简单方法。一个命令带上一个参数就行了。不需要第二个文件名。该文件会被直接更改。

+

+```

+$ dos2unix testfile.txt

+dos2unix: converting file testfile.txt to Unix format...

+```

+

+你应该看到文件长度减少,具体取决于它包含的行数。包含 100 行的文件可能会缩小 99 个字符,因为只有最后一行不会以 **CRLF** 字符结尾。

+

+之前:

+

+```

+-rw-rw-r-- 1 shs shs 121 Sep 14 19:11 testfile.txt

+```

+

+之后:

+

+```

+-rw-rw-r-- 1 shs shs 118 Sep 14 19:12 testfile.txt

+```

+

+如果你需要转换大量文件,不用每次修复一个。相反,将它们全部放在一个目录中并运行如下命令:

+

+```

+$ find . -type f -exec dos2unix {} \;

+```

+

+在此命令中,我们使用 find 查找常规文件,然后运行 **dos2unix** 命令一次转换一个。命令中的 {} 将被替换为文件名。运行时,你应该处于包含文件的目录中。此命令可能会损坏其他类型的文件,例如除了文本文件外在上下文中包含八进制 15 的文件(如,镜像文件中的字节)。

+

+#### sed

+

+你还可以使用流编辑器 **sed** 来删除回车符。但是,你必须提供第二个文件名。以下是例子:

+

+```

+$ sed -e “s/^M//” before.txt > after.txt

+```

+

+一件需要注意的重要的事情是,请不要输入你看到的字符。你必须按下 **Ctrl+V** 后跟 **Ctrl+M** 来输入 **^M**。 “s” 是替换命令。斜杠将我们要查找的文本(Ctrl + M)和要替换的文本(这里是空)分开。

+

+#### vi

+

+你甚至可以使用 **vi** 删除回车符(**Ctrl+M**),但这里假设你没有打开数百个文件,或许也在做一些其他的修改。你可以键入“**:**” 进入命令行,然后输入下面的字符串。与 **sed** 一样,命令中 **^M** 需要通过 **Ctrl+V** 输入 **^**,然后 **Ctrl+M** 插入**M**。 **%s**是替换操作,斜杠再次将我们要删除的字符和我们想要替换它的文本(空)分开。 “**g**”(全局)意味在所有行上执行。

+

+```

+:%s/^M//g

+```

+

+#### 总结

+

+**dos2unix** 命令可能是最容易记住的,也是最可靠地从文本中删除回车的方法。 其他选择使用起来有点困难,但它们提供相同的基本功能。

+

+在 [Facebook][3] 和 [LinkedIn][4] 上加入 Network World 社区,评论最热主题。

+

+--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

+

+via: https://www.networkworld.com/article/3438857/how-to-remove-carriage-returns-from-text-files-on-linux.html

+

+作者:[Sandra Henry-Stocker][a]

+选题:[lujun9972][b]

+译者:[geekpi](https://github.com/geekpi)

+校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

+

+本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

+

+[a]: https://www.networkworld.com/author/Sandra-Henry_Stocker/

+[b]: https://github.com/lujun9972

+[1]: https://www.flickr.com/photos/kmsiever/5895380540/in/photolist-9YXnf5-cNmpxq-2KEvib-rfecPZ-9snnkJ-2KAcDR-dTxzKW-6WdgaG-6H5i46-2KzTZX-7cnSw7-e3bUdi-a9meh9-Zm3pD-xiFhs-9Hz6YM-ar4DEx-4PXAhw-9wR4jC-cihLcs-asRFJc-9ueXvG-aoWwHq-atwL3T-ai89xS-dgnntH-5en8Te-dMUDd9-aSQVn-dyZqij-cg4SeS-abygkg-f2umXt-Xk129E-4YAeNn-abB6Hb-9313Wk-f9Tot-92Yfva-2KA7Sv-awSCtG-2KDPzb-eoPN6w-FE9oi-5VhaNf-eoQgx7-eoQogA-9ZWoYU-7dTGdG-5B1aSS

+[3]: https://www.facebook.com/NetworkWorld/

+[4]: https://www.linkedin.com/company/network-world