mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-03-24 02:20:09 +08:00

commit

f9f2a9bc24

@ -1,122 +0,0 @@

|

||||

#Translating by qhwdw [Recursion: dream within a dream][1]

|

||||

Recursion is magic, but it suffers from the most awkward introduction in programming books. They'll show you a recursive factorial implementation, then warn you that while it sort of works it's terribly slow and might crash due to stack overflows. "You could always dry your hair by sticking your head into the microwave, but watch out for intracranial pressure and head explosions. Or you can use a towel." No wonder people are suspicious of it. Which is too bad, because recursion is the single most powerful idea in algorithms.

|

||||

|

||||

Let's take a look at the classic recursive factorial:

|

||||

|

||||

Recursive Factorial - factorial.c

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

#include <stdio.h>

|

||||

|

||||

int factorial(int n)

|

||||

{

|

||||

int previous = 0xdeadbeef;

|

||||

|

||||

if (n == 0 || n == 1) {

|

||||

return 1;

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

previous = factorial(n-1);

|

||||

return n * previous;

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

int main(int argc)

|

||||

{

|

||||

int answer = factorial(5);

|

||||

printf("%d\n", answer);

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

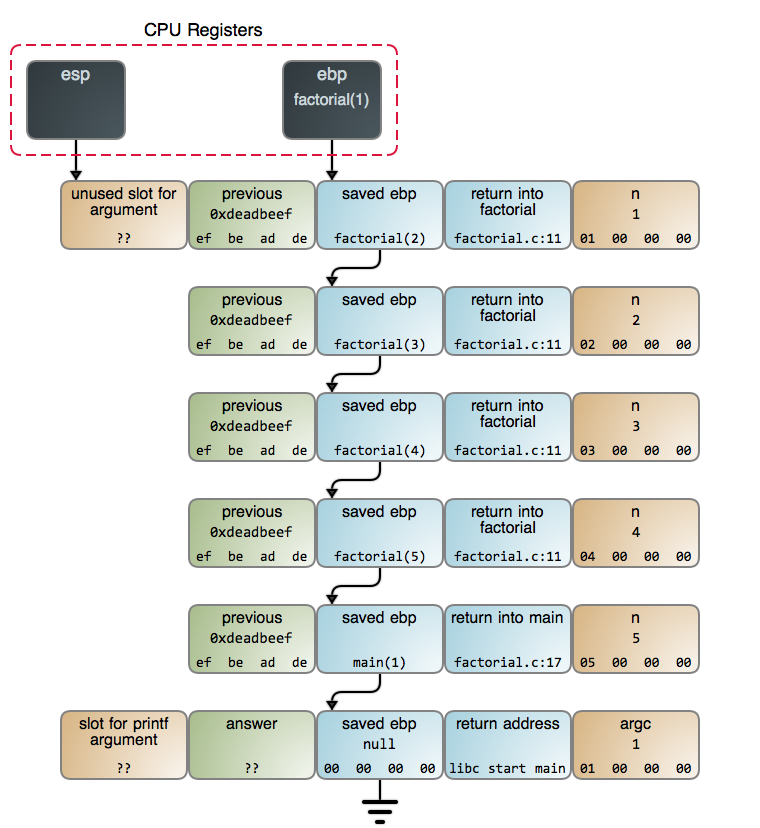

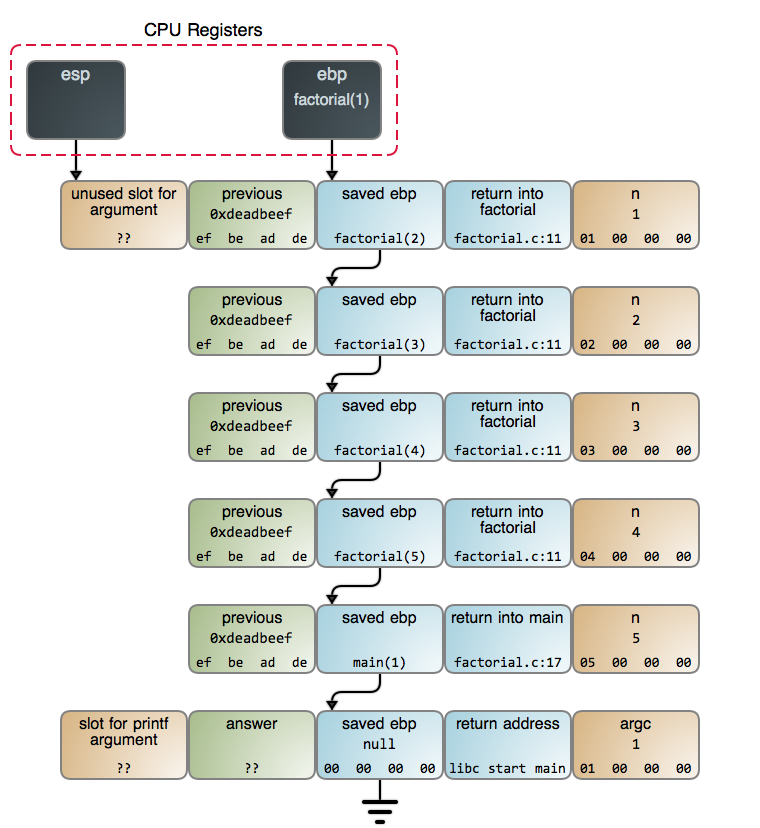

The idea of a function calling itself is mystifying at first. To make it concrete, here is exactly what is [on the stack][3] when factorial(5) is called and reaches n == 1:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Each call to factorial generates a new [stack frame][4]. The creation and [destruction][5] of these stack frames is what makes the recursive factorial slower than its iterative counterpart. The accumulation of these frames before the calls start returning is what can potentially exhaust stack space and crash your program.

|

||||

|

||||

These concerns are often theoretical. For example, the stack frames for factorial take 16 bytes each (this can vary depending on stack alignment and other factors). If you are running a modern x86 Linux kernel on a computer, you normally have 8 megabytes of stack space, so factorial could handle n up to ~512,000\. This is a [monstrously large result][6] that takes 8,971,833 bits to represent, so stack space is the least of our problems: a puny integer - even a 64-bit one - will overflow tens of thousands of times over before we run out of stack space.

|

||||

|

||||

We'll look at CPU usage in a moment, but for now let's take a step back from the bits and bytes and look at recursion as a general technique. Our factorial algorithm boils down to pushing integers N, N-1, ... 1 onto a stack, then multiplying them in reverse order. The fact we're using the program's call stack to do this is an implementation detail: we could allocate a stack on the heap and use that instead. While the call stack does have special properties, it's just another data structure at your disposal. I hope the diagram makes that clear.

|

||||

|

||||

Once you see the call stack as a data structure, something else becomes clear: piling up all those integers to multiply them afterwards is one dumbass idea. That is the real lameness of this implementation: it's using a screwdriver to hammer a nail. It's far more sensible to use an iterative process to calculate factorials.

|

||||

|

||||

But there are plenty of screws out there, so let's pick one. There is a traditional interview question where you're given a mouse in a maze, and you must help the mouse search for cheese. Suppose the mouse can turn either left or right in the maze. How would you model and solve this problem?

|

||||

|

||||

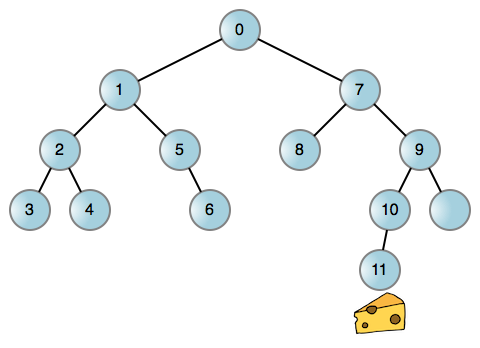

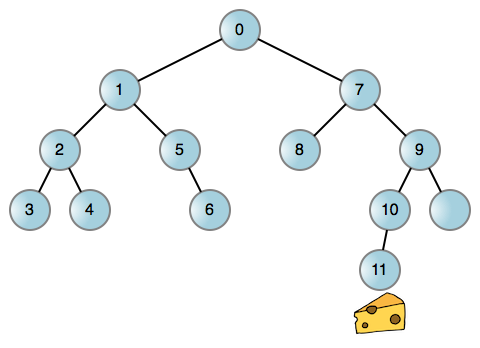

Like most problems in life, you can reduce this rodent quest to a graph, in particular a binary tree where the nodes represent positions in the maze. You could then have the mouse attempt left turns whenever possible, and backtrack to turn right when it reaches a dead end. Here's the mouse walk in an [example maze][7]:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Each edge (line) is a left or right turn taking our mouse to a new position. If either turn is blocked, the corresponding edge does not exist. Now we're talking! This process is inherently recursive whether you use the call stack or another data structure. But using the call stack is just so easy:

|

||||

|

||||

Recursive Maze Solver[download][2]

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

#include <stdio.h>

|

||||

#include "maze.h"

|

||||

|

||||

int explore(maze_t *node)

|

||||

{

|

||||

int found = 0;

|

||||

|

||||

if (node == NULL)

|

||||

{

|

||||

return 0;

|

||||

}

|

||||

if (node->hasCheese){

|

||||

return 1;// found cheese

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

found = explore(node->left) || explore(node->right);

|

||||

return found;

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

int main(int argc)

|

||||

{

|

||||

int found = explore(&maze);

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

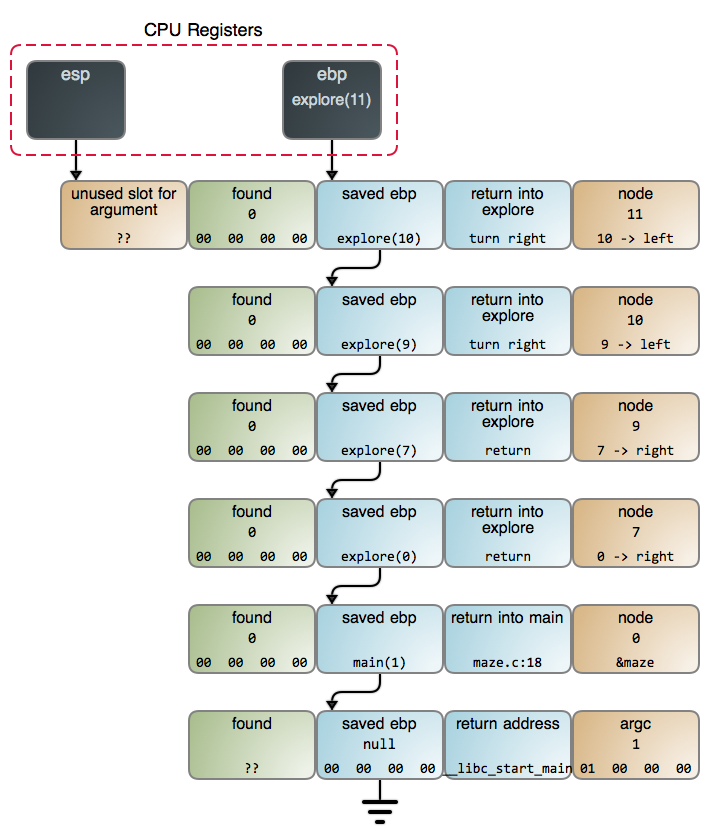

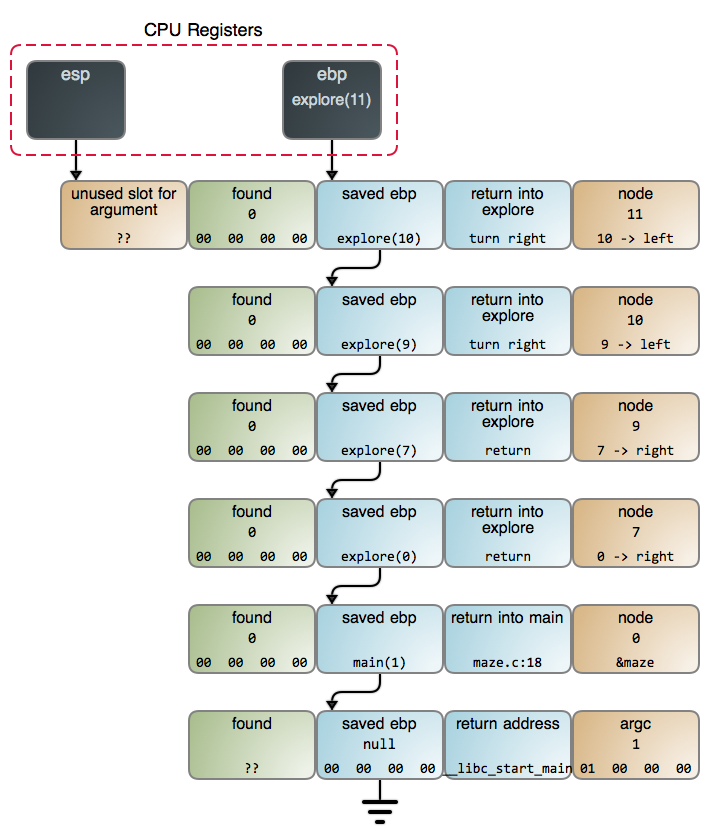

Below is the stack when we find the cheese in maze.c:13\. You can also see the detailed [GDB output][8] and [commands][9] used to gather data.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

This shows recursion in a much better light because it's a suitable problem. And that's no oddity: when it comes to algorithms, recursion is the rule, not the exception. It comes up when we search, when we traverse trees and other data structures, when we parse, when we sort: it's everywhere. You know how pi or e come up in math all the time because they're in the foundations of the universe? Recursion is like that: it's in the fabric of computation.

|

||||

|

||||

Steven Skienna's excellent [Algorithm Design Manual][10] is a great place to see that in action as he works through his "war stories" and shows the reasoning behind algorithmic solutions to real-world problems. It's the best resource I know of to develop your intuition for algorithms. Another good read is McCarthy's [original paper on LISP][11]. Recursion is both in its title and in the foundations of the language. The paper is readable and fun, it's always a pleasure to see a master at work.

|

||||

|

||||

Back to the maze. While it's hard to get away from recursion here, it doesn't mean it must be done via the call stack. You could for example use a string like RRLL to keep track of the turns, and rely on the string to decide on the mouse's next move. Or you can allocate something else to record the state of the cheese hunt. You'd still be implementing a recursive process, but rolling your own data structure.

|

||||

|

||||

That's likely to be more complex because the call stack fits like a glove. Each stack frame records not only the current node, but also the state of computation in that node (in this case, whether we've taken only the left, or are already attempting the right). Hence the code becomes trivial. Yet we sometimes give up this sweetness for fear of overflows and hopes of performance. That can be foolish.

|

||||

|

||||

As we've seen, the stack is large and frequently other constraints kick in before stack space does. One can also check the problem size and ensure it can be handled safely. The CPU worry is instilled chiefly by two widespread pathological examples: the dumb factorial and the hideous O(2n) [recursive Fibonacci][12] without memoization. These are not indicative of sane stack-recursive algorithms.

|

||||

|

||||

The reality is that stack operations are fast. Often the offsets to data are known exactly, the stack is hot in the [caches][13], and there are dedicated instructions to get things done. Meanwhile, there is substantial overhead involved in using your own heap-allocated data structures. It's not uncommon to see people write something that ends up more complex and less performant than call-stack recursion. Finally, modern CPUs are [pretty good][14] and often not the bottleneck. Be careful about sacrificing simplicity and as always with performance, [measure][15].

|

||||

|

||||

The next post is the last in this stack series, and we'll look at Tail Calls, Closures, and Other Fauna. Then it'll be time to visit our old friend, the Linux kernel. Thanks for reading!

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via:https://manybutfinite.com/post/recursion/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Gustavo Duarte][a]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/about/

|

||||

[1]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/recursion/

|

||||

[2]:https://manybutfinite.com/code/x86-stack/maze.c

|

||||

[3]:https://github.com/gduarte/blog/blob/master/code/x86-stack/factorial-gdb-output.txt

|

||||

[4]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/journey-to-the-stack

|

||||

[5]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/epilogues-canaries-buffer-overflows/

|

||||

[6]:https://gist.github.com/gduarte/9944878

|

||||

[7]:https://github.com/gduarte/blog/blob/master/code/x86-stack/maze.h

|

||||

[8]:https://github.com/gduarte/blog/blob/master/code/x86-stack/maze-gdb-output.txt

|

||||

[9]:https://github.com/gduarte/blog/blob/master/code/x86-stack/maze-gdb-commands.txt

|

||||

[10]:http://www.amazon.com/Algorithm-Design-Manual-Steven-Skiena/dp/1848000693/

|

||||

[11]:https://github.com/papers-we-love/papers-we-love/blob/master/comp_sci_fundamentals_and_history/recursive-functions-of-symbolic-expressions-and-their-computation-by-machine-parti.pdf

|

||||

[12]:http://stackoverflow.com/questions/360748/computational-complexity-of-fibonacci-sequence

|

||||

[13]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/intel-cpu-caches/

|

||||

[14]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/what-your-computer-does-while-you-wait/

|

||||

[15]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/performance-is-a-science

|

||||

122

translated/tech/20140410 Recursion- dream within a dream.md

Normal file

122

translated/tech/20140410 Recursion- dream within a dream.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,122 @@

|

||||

#[递归:梦中梦][1]

|

||||

递归是很神奇的,但是在大多数的编程类书藉中对递归讲解的并不好。它们只是给你展示一个递归阶乘的实现,然后警告你递归运行的很慢,并且还有可能因为栈缓冲区溢出而崩溃。“你可以将头伸进微波炉中去烘干你的头发,但是需要警惕颅内高压以及让你的头发生爆炸,或者你可以使用毛巾来擦干头发。”这就是人们不愿意使用递归的原因。这是很糟糕的,因为在算法中,递归是最强大的。

|

||||

|

||||

我们来看一下这个经典的递归阶乘:

|

||||

|

||||

递归阶乘 - factorial.c

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

#include <stdio.h>

|

||||

|

||||

int factorial(int n)

|

||||

{

|

||||

int previous = 0xdeadbeef;

|

||||

|

||||

if (n == 0 || n == 1) {

|

||||

return 1;

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

previous = factorial(n-1);

|

||||

return n * previous;

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

int main(int argc)

|

||||

{

|

||||

int answer = factorial(5);

|

||||

printf("%d\n", answer);

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

函数的目的是调用它自己,这在一开始是让人很难理解的。为了解具体的内容,当调用 `factorial(5)` 并且达到 `n == 1` 时,[在栈上][3] 究竟发生了什么?

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

每次调用 `factorial` 都生成一个新的 [栈帧][4]。这些栈帧的创建和 [销毁][5] 是递归慢于迭代的原因。在调用返回之前,累积的这些栈帧可能会耗尽栈空间,进而使你的程序崩溃。

|

||||

|

||||

而这些担心经常是存在于理论上的。例如,对于每个 `factorial` 的栈帧取 16 字节(这可能取决于栈排列以及其它因素)。如果在你的电脑上运行着现代的 x86 的 Linux 内核,一般情况下你拥有 8 GB 的栈空间,因此,`factorial` 最多可以被运行 ~512,000 次。这是一个 [巨大无比的结果][6],它相当于 8,971,833 比特,因此,栈空间根本就不是什么问题:一个极小的整数 - 甚至是一个 64 位的整数 - 在我们的栈空间被耗尽之前就早已经溢出了成千上万次了。

|

||||

|

||||

过一会儿我们再去看 CPU 的使用,现在,我们先从比特和字节回退一步,把递归看作一种通用技术。我们的阶乘算法总结为将整数 N、N-1、 … 1 推入到一个栈,然后将它们按相反的顺序相乘。实际上我们使用了程序调用栈来实现这一点,这是它的细节:我们在堆上分配一个栈并使用它。虽然调用栈具有特殊的特性,但是,你只是把它用作一种另外的数据结构。我希望示意图可以让你明白这一点。

|

||||

|

||||

当你看到栈调用作为一种数据结构使用,有些事情将变得更加清晰明了:将那些整数堆积起来,然后再将它们相乘,这并不是一个好的想法。那是一种有缺陷的实现:就像你拿螺丝刀去钉钉子一样。相对更合理的是使用一个迭代过程去计算阶乘。

|

||||

|

||||

但是,螺丝钉太多了,我们只能挑一个。有一个经典的面试题,在迷宫里有一只老鼠,你必须帮助这只老鼠找到一个奶酪。假设老鼠能够在迷宫中向左或者向右转弯。你该怎么去建模来解决这个问题?

|

||||

|

||||

就像现实生活中的很多问题一样,你可以将这个老鼠找奶酪的问题简化为一个图,一个二叉树的每个结点代表在迷宫中的一个位置。然后你可以让老鼠在任何可能的地方都左转,而当它进入一个死胡同时,再返回来右转。这是一个老鼠行走的 [迷宫示例][7]:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

每到边缘(线)都让老鼠左转或者右转来到达一个新的位置。如果向哪边转都被拦住,说明相关的边缘不存在。现在,我们来讨论一下!这个过程无论你是调用栈还是其它数据结构,它都离不开一个递归的过程。而使用调用栈是非常容易的:

|

||||

|

||||

递归迷宫求解 [下载][2]

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

#include <stdio.h>

|

||||

#include "maze.h"

|

||||

|

||||

int explore(maze_t *node)

|

||||

{

|

||||

int found = 0;

|

||||

|

||||

if (node == NULL)

|

||||

{

|

||||

return 0;

|

||||

}

|

||||

if (node->hasCheese){

|

||||

return 1;// found cheese

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

found = explore(node->left) || explore(node->right);

|

||||

return found;

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

int main(int argc)

|

||||

{

|

||||

int found = explore(&maze);

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

当我们在 `maze.c:13` 中找到奶酪时,栈的情况如下图所示。你也可以在 [GDB 输出][8] 中看到更详细的数据,它是使用 [命令][9] 采集的数据。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

它展示了递归的良好表现,因为这是一个适合使用递归的问题。而且这并不奇怪:当涉及到算法时,递归是一种使用较多的算法,而不是被排除在外的。当进行搜索时、当进行遍历树和其它数据结构时、当进行解析时、当需要排序时:它的用途无处不在。正如众所周知的 pi 或者 e,它们在数学中像“神”一样的存在,因为它们是宇宙万物的基础,而递归也和它们一样:只是它在计算的结构中。

|

||||

|

||||

Steven Skienna 的优秀著作 [算法设计指南][10] 的精彩之处在于,他通过“战争故事” 作为手段来诠释工作,以此来展示解决现实世界中的问题背后的算法。这是我所知道的拓展你的算法知识的最佳资源。另一个较好的做法是,去读 McCarthy 的 [LISP 上的原创论文][11]。递归在语言中既是它的名字也是它的基本原理。这篇论文既可读又有趣,在工作中能看到大师的作品是件让人兴奋的事情。

|

||||

|

||||

回到迷宫问题上。虽然它在这里很难离开递归,但是并不意味着必须通过调用栈的方式来实现。你可以使用像 “RRLL” 这样的字符串去跟踪转向,然后,依据这个字符串去决定老鼠下一步的动作。或者你可以分配一些其它的东西来记录奶酪的状态。你仍然是去实现一个递归的过程,但是需要你实现一个自己的数据结构。

|

||||

|

||||

那样似乎更复杂一些,因为栈调用更合适。每个栈帧记录的不仅是当前节点,也记录那个节点上的计算状态(在这个案例中,我们是否只让它走左边,或者已经尝试向右)。因此,代码已经变得不重要了。然而,有时候我们因为害怕溢出和期望中的性能而放弃这种优秀的算法。那是很愚蠢的!

|

||||

|

||||

正如我们所见,栈空间是非常大的,在耗尽栈空间之前往往会遇到其它的限制。一方面可以通过检查问题大小来确保它能够被安全地处理。而对 CPU 的担心是由两个广为流传的有问题的示例所导致的:哑阶乘(dumb factorial)和可怕的无记忆的 O(2n) [Fibonacci 递归][12]。它们并不是栈递归算法的正确代表。

|

||||

|

||||

事实上栈操作是非常快的。通常,栈对数据的偏移是非常准确的,它在 [缓存][13] 中是热点,并且是由专门的指令来操作它。同时,使用你自己定义的堆上分配的数据结构的相关开销是很大的。经常能看到人们写的一些比栈调用递归更复杂、性能更差的实现方法。最后,现代的 CPU 的性能都是 [非常好的][14] ,并且一般 CPU 不会是性能瓶颈所在。要注意牺牲简单性与保持性能的关系。[测量][15]。

|

||||

|

||||

下一篇文章将是探秘栈系列的最后一篇了,我们将了解尾调用、闭包、以及其它相关概念。然后,我们就该深入我们的老朋友—— Linux 内核了。感谢你的阅读!

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via:https://manybutfinite.com/post/recursion/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Gustavo Duarte][a]

|

||||

译者:[qhwdw](https://github.com/qhwdw)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/about/

|

||||

[1]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/recursion/

|

||||

[2]:https://manybutfinite.com/code/x86-stack/maze.c

|

||||

[3]:https://github.com/gduarte/blog/blob/master/code/x86-stack/factorial-gdb-output.txt

|

||||

[4]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/journey-to-the-stack

|

||||

[5]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/epilogues-canaries-buffer-overflows/

|

||||

[6]:https://gist.github.com/gduarte/9944878

|

||||

[7]:https://github.com/gduarte/blog/blob/master/code/x86-stack/maze.h

|

||||

[8]:https://github.com/gduarte/blog/blob/master/code/x86-stack/maze-gdb-output.txt

|

||||

[9]:https://github.com/gduarte/blog/blob/master/code/x86-stack/maze-gdb-commands.txt

|

||||

[10]:http://www.amazon.com/Algorithm-Design-Manual-Steven-Skiena/dp/1848000693/

|

||||

[11]:https://github.com/papers-we-love/papers-we-love/blob/master/comp_sci_fundamentals_and_history/recursive-functions-of-symbolic-expressions-and-their-computation-by-machine-parti.pdf

|

||||

[12]:http://stackoverflow.com/questions/360748/computational-complexity-of-fibonacci-sequence

|

||||

[13]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/intel-cpu-caches/

|

||||

[14]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/what-your-computer-does-while-you-wait/

|

||||

[15]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/performance-is-a-science

|

||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user