mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-03-27 02:30:10 +08:00

Translated by qhwdw

This commit is contained in:

parent

fc3731c90d

commit

e3201483d9

@ -1,153 +0,0 @@

|

||||

# Translating by qhwdw System Calls Make the World Go Round

|

||||

|

||||

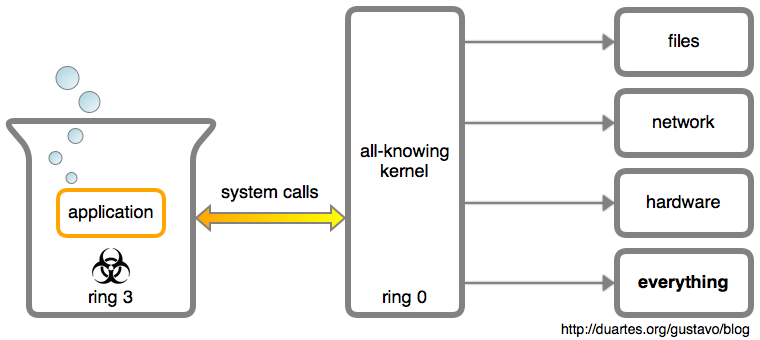

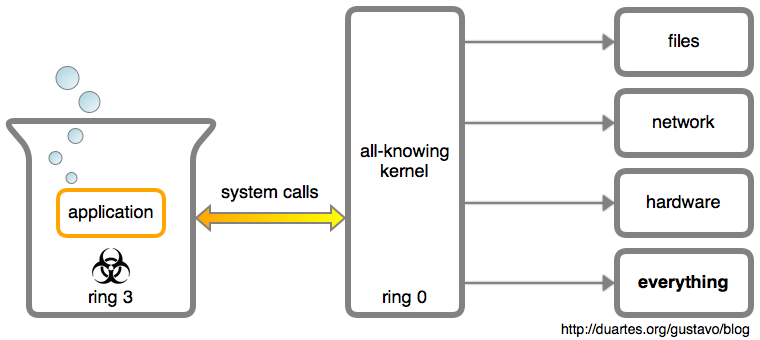

I hate to break it to you, but a user application is a helpless brain in a vat:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Every interaction with the outside world is mediated by the kernel through system calls. If an app saves a file, writes to the terminal, or opens a TCP connection, the kernel is involved. Apps are regarded as highly suspicious: at best a bug-ridden mess, at worst the malicious brain of an evil genius.

|

||||

|

||||

These system calls are function calls from an app into the kernel. They use a specific mechanism for safety reasons, but really you're just calling the kernel's API. The term "system call" can refer to a specific function offered by the kernel (e.g., the open() system call) or to the calling mechanism. You can also say syscall for short.

|

||||

|

||||

This post looks at system calls, how they differ from calls to a library, and tools to poke at this OS/app interface. A solid understanding of what happens within an app versus what happens through the OS can turn an impossible-to-fix problem into a quick, fun puzzle.

|

||||

|

||||

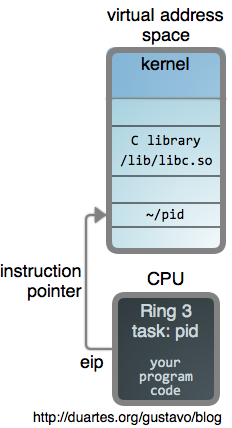

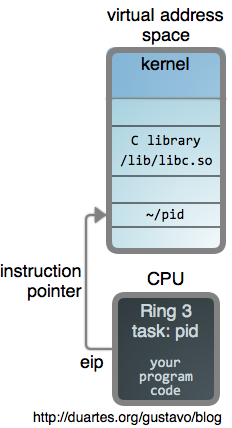

So here's a running program, a user process:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

It has a private [virtual address space][2], its very own memory sandbox. The vat, if you will. In its address space, the program's binary file plus the libraries it uses are all [memory mapped][3]. Part of the address space maps the kernel itself.

|

||||

|

||||

Below is the code for our program, pid, which simply retrieves its process id via [getpid(2)][4]:

|

||||

|

||||

pid.c[download][1]

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

||||

```

|

||||

123456789

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

|

||||

```

|

||||

#include #include #include int main(){ pid_t p = getpid(); printf("%d\n", p);}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

||||

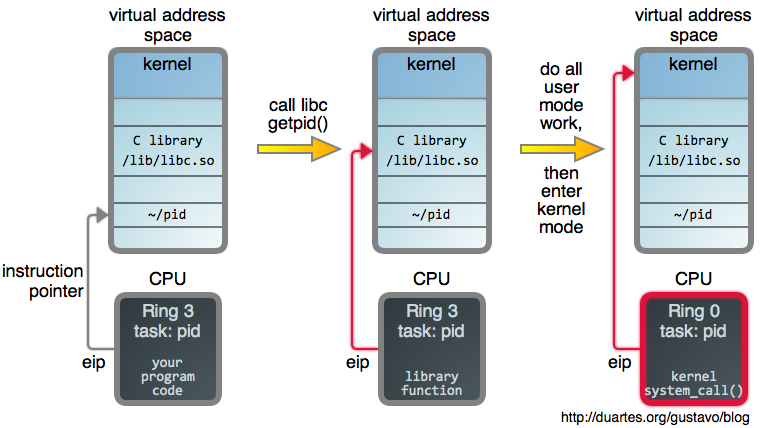

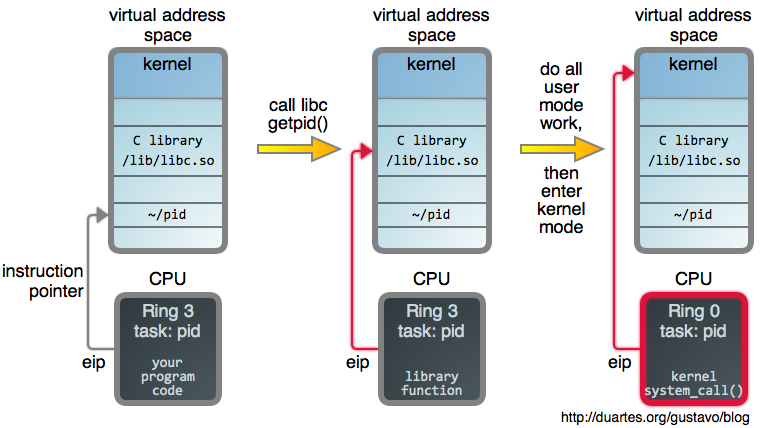

In Linux, a process isn't born knowing its PID. It must ask the kernel, so this requires a system call:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

It all starts with a call to the C library's [getpid()][5], which is a wrapper for the system call. When you call functions like open(2), read(2), and friends, you're calling these wrappers. This is true for many languages where the native methods ultimately end up in libc.

|

||||

|

||||

Wrappers offer convenience atop the bare-bones OS API, helping keep the kernel lean. Lines of code is where bugs live, and all kernel code runs in privileged mode, where mistakes can be disastrous. Anything that can be done in user mode should be done in user mode. Let the libraries offer friendly methods and fancy argument processing a la printf(3).

|

||||

|

||||

Compared to web APIs, this is analogous to building the simplest possible HTTP interface to a service and then offering language-specific libraries with helper methods. Or maybe some caching, which is what libc's getpid() does: when first called it actually performs a system call, but the PID is then cached to avoid the syscall overhead in subsequent invocations.

|

||||

|

||||

Once the wrapper has done its initial work it's time to jump into hyperspace the kernel. The mechanics of this transition vary by processor architecture. In Intel processors, arguments and the [syscall number][6] are [loaded into registers][7], then an [instruction][8] is executed to put the CPU in [privileged mode][9] and immediately transfer control to a global syscall [entry point][10] within the kernel. If you're interested in details, David Drysdale has two great articles in LWN ([first][11], [second][12]).

|

||||

|

||||

The kernel then uses the syscall number as an [index][13] into [sys_call_table][14], an array of function pointers to each syscall implementation. Here, [sys_getpid][15] is called:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

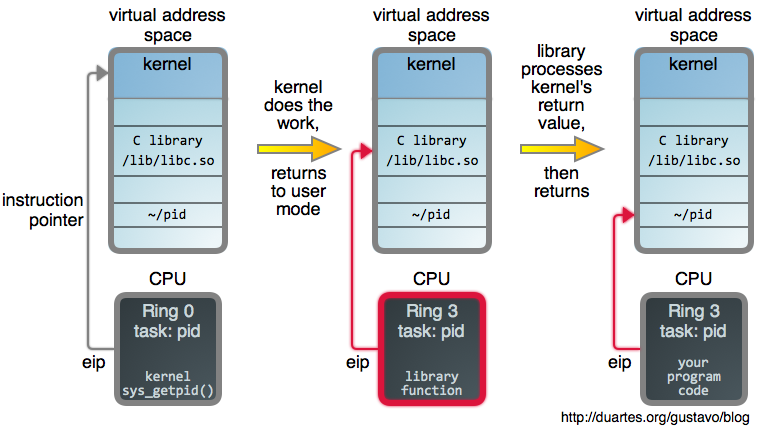

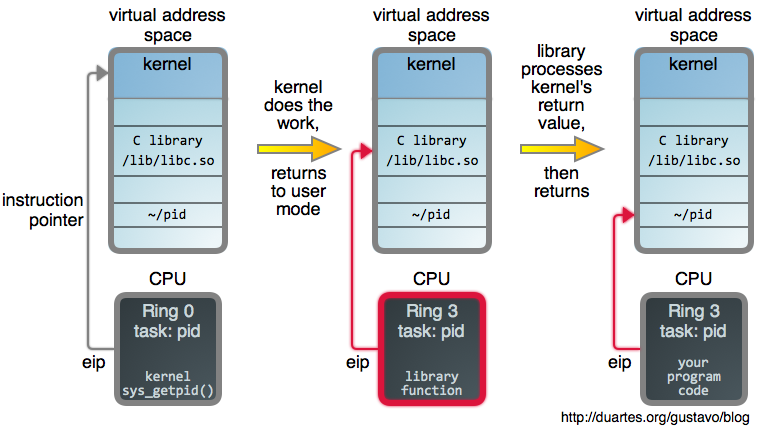

In Linux, syscall implementations are mostly arch-independent C functions, sometimes [trivial][16], insulated from the syscall mechanism by the kernel's excellent design. They are regular code working on general data structures. Well, apart from being completely paranoid about argument validation.

|

||||

|

||||

Once their work is done they return normally, and the arch-specific code takes care of transitioning back into user mode where the wrapper does some post processing. In our example, [getpid(2)][17] now caches the PID returned by the kernel. Other wrappers might set the global errno variable if the kernel returns an error. Small things to let you know GNU cares.

|

||||

|

||||

If you want to be raw, glibc offers the [syscall(2)][18] function, which makes a system call without a wrapper. You can also do so yourself in assembly. There's nothing magical or privileged about a C library.

|

||||

|

||||

This syscall design has far-reaching consequences. Let's start with the incredibly useful [strace(1)][19], a tool you can use to spy on system calls made by Linux processes (in Macs, see [dtruss(1m)][20] and the amazing [dtrace][21]; in Windows, see [sysinternals][22]). Here's strace on pid:

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

||||

```

|

||||

1234567891011121314151617181920

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

|

||||

```

|

||||

~/code/x86-os$ strace ./pidexecve("./pid", ["./pid"], [/* 20 vars */]) = 0brk(0) = 0x9aa0000access("/etc/ld.so.nohwcap", F_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)mmap2(NULL, 8192, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0xb7767000access("/etc/ld.so.preload", R_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)open("/etc/ld.so.cache", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3fstat64(3, {st_mode=S_IFREG|0644, st_size=18056, ...}) = 0mmap2(NULL, 18056, PROT_READ, MAP_PRIVATE, 3, 0) = 0xb7762000close(3) = 0[...snip...]getpid() = 14678fstat64(1, {st_mode=S_IFCHR|0600, st_rdev=makedev(136, 1), ...}) = 0mmap2(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0xb7766000write(1, "14678\n", 614678) = 6exit_group(6) = ?

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

||||

Each line of output shows a system call, its arguments, and a return value. If you put getpid(2) in a loop running 1000 times, you would still have only one getpid() syscall because of the PID caching. We can also see that printf(3) calls write(2) after formatting the output string.

|

||||

|

||||

strace can start a new process and also attach to an already running one. You can learn a lot by looking at the syscalls made by different programs. For example, what does the sshd daemon do all day?

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

||||

```

|

||||

1234567891011121314151617181920212223242526272829

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

|

||||

```

|

||||

~/code/x86-os$ ps ax | grep sshd12218 ? Ss 0:00 /usr/sbin/sshd -D~/code/x86-os$ sudo strace -p 12218Process 12218 attached - interrupt to quitselect(7, [3 4], NULL, NULL, NULL[ ... nothing happens ... No fun, it's just waiting for a connection using select(2) If we wait long enough, we might see new keys being generated and so on, but let's attach again, tell strace to follow forks (-f), and connect via SSH]~/code/x86-os$ sudo strace -p 12218 -f[lots of calls happen during an SSH login, only a few shown][pid 14692] read(3, "-----BEGIN RSA PRIVATE KEY-----\n"..., 1024) = 1024[pid 14692] open("/usr/share/ssh/blacklist.RSA-2048", O_RDONLY|O_LARGEFILE) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)[pid 14692] open("/etc/ssh/blacklist.RSA-2048", O_RDONLY|O_LARGEFILE) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)[pid 14692] open("/etc/ssh/ssh_host_dsa_key", O_RDONLY|O_LARGEFILE) = 3[pid 14692] open("/etc/protocols", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 4[pid 14692] read(4, "# Internet (IP) protocols\n#\n# Up"..., 4096) = 2933[pid 14692] open("/etc/hosts.allow", O_RDONLY) = 4[pid 14692] open("/lib/i386-linux-gnu/libnss_dns.so.2", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 4[pid 14692] stat64("/etc/pam.d", {st_mode=S_IFDIR|0755, st_size=4096, ...}) = 0[pid 14692] open("/etc/pam.d/common-password", O_RDONLY|O_LARGEFILE) = 8[pid 14692] open("/etc/pam.d/other", O_RDONLY|O_LARGEFILE) = 4

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

||||

SSH is a large chunk to bite off, but it gives a feel for strace usage. Being able to see which files an app opens can be useful ("where the hell is this config coming from?"). If you have a process that appears stuck, you can strace it and see what it might be doing via system calls. When some app is quitting unexpectedly without a proper error message, check if a syscall failure explains it. You can also use filters, time each call, and so so:

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

||||

```

|

||||

123456789

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

|

||||

```

|

||||

~/code/x86-os$ strace -T -e trace=recv curl -silent www.google.com. > /dev/nullrecv(3, "HTTP/1.1 200 OK\r\nDate: Wed, 05 N"..., 16384, 0) = 4164 <0.000007>recv(3, "fl a{color:#36c}a:visited{color:"..., 16384, 0) = 2776 <0.000005>recv(3, "adient(top,#4d90fe,#4787ed);filt"..., 16384, 0) = 4164 <0.000007>recv(3, "gbar.up.spd(b,d,1,!0);break;case"..., 16384, 0) = 2776 <0.000006>recv(3, "$),a.i.G(!0)),window.gbar.up.sl("..., 16384, 0) = 1388 <0.000004>recv(3, "margin:0;padding:5px 8px 0 6px;v"..., 16384, 0) = 1388 <0.000007>recv(3, "){window.setTimeout(function(){v"..., 16384, 0) = 1484 <0.000006>

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

||||

I encourage you to explore these tools in your OS. Using them well is like having a super power.

|

||||

|

||||

But enough useful stuff, let's go back to design. We've seen that a userland app is trapped in its virtual address space running in ring 3 (unprivileged). In general, tasks that involve only computation and memory accesses do not require syscalls. For example, C library functions like [strlen(3)][23] and [memcpy(3)][24] have nothing to do with the kernel. Those happen within the app.

|

||||

|

||||

The man page sections for a C library function (the 2 and 3 in parenthesis) also offer clues. Section 2 is used for system call wrappers, while section 3 contains other C library functions. However, as we saw with printf(3), a library function might ultimately make one or more syscalls.

|

||||

|

||||

If you're curious, here are full syscall listings for [Linux][25] (also [Filippo's list][26]) and [Windows][27]. They have ~310 and ~460 system calls, respectively. It's fun to look at those because, in a way, they represent all that software can do on a modern computer. Plus, you might find gems to help with things like interprocess communication and performance. This is an area where "Those who do not understand Unix are condemned to reinvent it, poorly."

|

||||

|

||||

Many syscalls perform tasks that take [eons][28] compared to CPU cycles, for example reading from a hard drive. In those situations the calling process is often put to sleep until the underlying work is completed. Because CPUs are so fast, your average program is I/O bound and spends most of its life sleeping, waiting on syscalls. By contrast, if you strace a program busy with a computational task, you often see no syscalls being invoked. In such a case, [top(1)][29] would show intense CPU usage.

|

||||

|

||||

The overhead involved in a system call can be a problem. For example, SSDs are so fast that general OS overhead can be [more expensive][30] than the I/O operation itself. Programs doing large numbers of reads and writes can also have OS overhead as their bottleneck. [Vectored I/O][31] can help some. So can [memory mapped files][32], which allow a program to read and write from disk using only memory access. Analogous mappings exist for things like video card memory. Eventually, the economics of cloud computing might lead us to kernels that eliminate or minimize user/kernel mode switches.

|

||||

|

||||

Finally, syscalls have interesting security implications. One is that no matter how obfuscated a binary, you can still examine its behavior by looking at the system calls it makes. This can be used to detect malware, for example. We can also record profiles of a known program's syscall usage and alert on deviations, or perhaps whitelist specific syscalls for programs so that exploiting vulnerabilities becomes harder. We have a ton of research in this area, a number of tools, but not a killer solution yet.

|

||||

|

||||

And that's it for system calls. I'm sorry for the length of this post, I hope it was helpful. More (and shorter) next week, [RSS][33] and [Twitter][34]. Also, last night I made a promise to the universe. This post is dedicated to the glorious Clube Atlético Mineiro.

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via:https://manybutfinite.com/post/system-calls/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Gustavo Duarte][a]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/about/

|

||||

[1]:https://manybutfinite.com/code/x86-os/pid.c

|

||||

[2]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/anatomy-of-a-program-in-memory

|

||||

[3]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/page-cache-the-affair-between-memory-and-files/

|

||||

[4]:http://linux.die.net/man/2/getpid

|

||||

[5]:https://sourceware.org/git/?p=glibc.git;a=blob;f=sysdeps/unix/sysv/linux/getpid.c;h=937b1d4e113b1cff4a5c698f83d662e130d596af;hb=4c6da7da9fb1f0f94e668e6d2966a4f50a7f0d85#l49

|

||||

[6]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/arch/x86/syscalls/syscall_64.tbl#L48

|

||||

[7]:https://sourceware.org/git/?p=glibc.git;a=blob;f=sysdeps/unix/sysv/linux/x86_64/sysdep.h;h=4a619dafebd180426bf32ab6b6cb0e5e560b718a;hb=4c6da7da9fb1f0f94e668e6d2966a4f50a7f0d85#l139

|

||||

[8]:https://sourceware.org/git/?p=glibc.git;a=blob;f=sysdeps/unix/sysv/linux/x86_64/sysdep.h;h=4a619dafebd180426bf32ab6b6cb0e5e560b718a;hb=4c6da7da9fb1f0f94e668e6d2966a4f50a7f0d85#l179

|

||||

[9]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/cpu-rings-privilege-and-protection

|

||||

[10]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/arch/x86/kernel/entry_64.S#L354-L386

|

||||

[11]:http://lwn.net/Articles/604287/

|

||||

[12]:http://lwn.net/Articles/604515/

|

||||

[13]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/arch/x86/kernel/entry_64.S#L422

|

||||

[14]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/arch/x86/kernel/syscall_64.c#L25

|

||||

[15]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/kernel/sys.c#L800-L809

|

||||

[16]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/kernel/sys.c#L800-L859

|

||||

[17]:http://linux.die.net/man/2/getpid

|

||||

[18]:http://linux.die.net/man/2/syscall

|

||||

[19]:http://linux.die.net/man/1/strace

|

||||

[20]:https://developer.apple.com/library/mac/documentation/Darwin/Reference/ManPages/man1/dtruss.1m.html

|

||||

[21]:http://dtrace.org/blogs/brendan/2011/10/10/top-10-dtrace-scripts-for-mac-os-x/

|

||||

[22]:http://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/sysinternals/bb842062.aspx

|

||||

[23]:http://linux.die.net/man/3/strlen

|

||||

[24]:http://linux.die.net/man/3/memcpy

|

||||

[25]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/arch/x86/syscalls/syscall_64.tbl

|

||||

[26]:https://filippo.io/linux-syscall-table/

|

||||

[27]:http://j00ru.vexillium.org/ntapi/

|

||||

[28]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/what-your-computer-does-while-you-wait/

|

||||

[29]:http://linux.die.net/man/1/top

|

||||

[30]:http://danluu.com/clwb-pcommit/

|

||||

[31]:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vectored_I/O

|

||||

[32]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/page-cache-the-affair-between-memory-and-files/

|

||||

[33]:http://feeds.feedburner.com/GustavoDuarte

|

||||

[34]:http://twitter.com/food4hackers

|

||||

164

translated/tech/20141106 System Calls Make the World Go Round.md

Normal file

164

translated/tech/20141106 System Calls Make the World Go Round.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,164 @@

|

||||

# 系统调用,让世界转起来!

|

||||

|

||||

我其实不想将它分解开给你看,一个用户应用程序在整个系统中就像一个可怜的孤儿一样无依无靠:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

它与外部世界的每个交流都要在内核的帮助下通过系统调用才能完成。一个应用程序要想保存一个文件、写到终端、或者打开一个 TCP 连接,内核都要参与。应用程序是被内核高度怀疑的:认为它到处充斥着 bugs,而最糟糕的是那些充满邪恶想法的天才大脑(写的恶意程序)。

|

||||

|

||||

这些系统调用是从一个应用程序到内核的函数调用。它们因为安全考虑使用一个特定的机制,实际上你只是调用了内核的 API。“系统调用”这个术语指的是调用由内核提供的特定功能(比如,系统调用 open())或者是调用途径。你也可以简称为:syscall。

|

||||

|

||||

这篇文章讲解系统调用,系统调用与调用一个库有何区别,以及在操作系统/应用程序接口上的刺探工具。如果想彻底了解应用程序借助操作系统都发生的哪些事情?那么就可以将一个不可能解决的问题转变成一个快速而有趣的难题。

|

||||

|

||||

因此,下图是一个运行着的应用程序,一个用户进程:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

它有一个私有的 [虚拟地址空间][2]—— 它自己的内存沙箱。整个系统都在地址空间中,程序的二进制文件加上它所需要的库全部都 [被映射到内存中][3]。内核自身也映射为地址空间的一部分。

|

||||

|

||||

下面是我们程序的代码和 PID,进程的 PID 可以通过 [getpid(2)][4]:

|

||||

|

||||

pid.c [download][1]

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

||||

```

|

||||

123456789

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

|

||||

```

|

||||

#include #include #include int main(){ pid_t p = getpid(); printf("%d\n", p);}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

||||

**(致校对:本文的所有代码部分都出现了排版错误,请与原文核对确认!!)**

|

||||

|

||||

在 Linux 中,一个进程并不是一出生就知道它的 PID。要想知道它的 PID,它必须去询问内核,因此,这个询问请求也是一个系统调用:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

它的第一步是开始于调用一个 C 库的 [getpid()][5],它是系统调用的一个封装。当你调用一些功能时,比如,open(2)、read(2)、以及相关的一些支持时,你就调用了这些封装。其实,对于大多数编程语言在这一块的原生方法,最终都是在 libc 中完成的。

|

||||

|

||||

极简设计的操作系统都提供了方便的 API 封装,这样可以保持内核的简洁。所有的内核代码运行在特权模式下,有 bugs 的内核代码行将会产生致命的后果。在用户模式下做的任何事情都是在用户模式中完成的。由库来提供友好的方法和想要的参数处理,像 printf(3) 这样。

|

||||

|

||||

我们拿一个 web APIs 进行比较,内核的封装方式与构建一个简单易行的 HTTP 接口去提供服务是类似的,然后使用特定语言的守护方法去提供特定语言的库。或者也可能有一些缓存,它是库的 getpid() 完成的内容:首次调用时,它真实地去执行了一个系统调用,然后,它缓存了 PID,这样就可以避免后续调用时的系统调用开销。

|

||||

|

||||

一旦封装完成,它做的第一件事就是进入了超空间(hyperspace)的内核(译者注:一个快速而安全的计算环境,独立于操作系统而存在)。这种转换机制因处理器架构设计不同而不同。(译者注:就是前一段时间爆出的存在于处理器硬件中的运行于 Ring -3 的操作系统,比如,Intel 的 ME)在 Intel 处理器中,参数和 [系统调用号][6] 是 [加载到寄存器中的][7],然后,运行一个 [指令][8] 将 CPU 置于 [特权模式][9] 中,并立即将控制权转移到内核中的全局系统调用 [入口][10]。如果你对这些细节感兴趣,David Drysdale 在 LWN 上有两篇非常好的文章([第一篇][11],[第二篇][12])。

|

||||

|

||||

内核然后使用这个系统调用号作为进入 [sys_call_table][14] 的一个 [索引][13],它是一个函数指针到每个系统调用实现的数组。在这里,调用 了 [sys_getpid][15]:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

在 Linux 中,系统调用大多数都实现为独立的 C 函数,有时候这样做 [很琐碎][16],但是通过内核优秀的设计,系统调用被严格隔离。它们是工作在一般数据结构中的普通代码。关于这些争论的验证除了完全偏执的以外,其它的还是非常好的。

|

||||

|

||||

一旦它们的工作完成,它们就会正常返回,然后,根据特定代码转回到用户模式,封装将在那里继续做一些后续处理工作。在我们的例子中,[getpid(2)][17] 现在缓存了由内核返回的 PID。如果内核返回了一个错误,另外的封装可以去设置全局 errno 变量。让你知道 GNU 所关心的一些小事。

|

||||

|

||||

如果你想看未处理的原生内容,glibc 提供了 [syscall(2)][18] 函数,它可以不通过封装来产生一个系统调用。你也可以通过它来做一个你自己的封装。这对一个 C 库来说,并不神奇,也不是保密的。

|

||||

|

||||

这种系统调用的设计影响是很深远的。我们从一个非常有用的 [strace(1)][19] 开始,这个工具可以用来监视 Linux 进程的系统调用(在 Mac 上,看 [dtruss(1m)][20] 和神奇的 [dtrace][21];在 Windows 中,看 [sysinternals][22])。这里在 pid 上的跟踪:

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

||||

```

|

||||

1234567891011121314151617181920

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

|

||||

```

|

||||

~/code/x86-os$ strace ./pidexecve("./pid", ["./pid"], [/* 20 vars */]) = 0brk(0) = 0x9aa0000access("/etc/ld.so.nohwcap", F_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)mmap2(NULL, 8192, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0xb7767000access("/etc/ld.so.preload", R_OK) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)open("/etc/ld.so.cache", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3fstat64(3, {st_mode=S_IFREG|0644, st_size=18056, ...}) = 0mmap2(NULL, 18056, PROT_READ, MAP_PRIVATE, 3, 0) = 0xb7762000close(3) = 0[...snip...]getpid() = 14678fstat64(1, {st_mode=S_IFCHR|0600, st_rdev=makedev(136, 1), ...}) = 0mmap2(NULL, 4096, PROT_READ|PROT_WRITE, MAP_PRIVATE|MAP_ANONYMOUS, -1, 0) = 0xb7766000write(1, "14678\n", 614678) = 6exit_group(6) = ?

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

||||

输出的每一行都显示了一个系统调用 、它的参数、以及返回值。如果你在一个循环中将 getpid(2) 运行 1000 次,你就会发现始终只有一个 getpid() 系统调用,因为,它的 PID 已经被缓存了。我们也可以看到在格式化输出字符串之后,printf(3) 调用了 write(2)。

|

||||

|

||||

strace 可以开始一个新进程,也可以附加到一个已经运行的进程上。你可以通过不同程序的系统调用学到很多的东西。例如,sshd 守护进程一天都干了什么?

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

||||

```

|

||||

1234567891011121314151617181920212223242526272829

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

|

||||

```

|

||||

~/code/x86-os$ ps ax | grep sshd12218 ? Ss 0:00 /usr/sbin/sshd -D~/code/x86-os$ sudo strace -p 12218Process 12218 attached - interrupt to quitselect(7, [3 4], NULL, NULL, NULL[ ... nothing happens ... No fun, it's just waiting for a connection using select(2) If we wait long enough, we might see new keys being generated and so on, but let's attach again, tell strace to follow forks (-f), and connect via SSH]~/code/x86-os$ sudo strace -p 12218 -f[lots of calls happen during an SSH login, only a few shown][pid 14692] read(3, "-----BEGIN RSA PRIVATE KEY-----\n"..., 1024) = 1024[pid 14692] open("/usr/share/ssh/blacklist.RSA-2048", O_RDONLY|O_LARGEFILE) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)[pid 14692] open("/etc/ssh/blacklist.RSA-2048", O_RDONLY|O_LARGEFILE) = -1 ENOENT (No such file or directory)[pid 14692] open("/etc/ssh/ssh_host_dsa_key", O_RDONLY|O_LARGEFILE) = 3[pid 14692] open("/etc/protocols", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 4[pid 14692] read(4, "# Internet (IP) protocols\n#\n# Up"..., 4096) = 2933[pid 14692] open("/etc/hosts.allow", O_RDONLY) = 4[pid 14692] open("/lib/i386-linux-gnu/libnss_dns.so.2", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 4[pid 14692] stat64("/etc/pam.d", {st_mode=S_IFDIR|0755, st_size=4096, ...}) = 0[pid 14692] open("/etc/pam.d/common-password", O_RDONLY|O_LARGEFILE) = 8[pid 14692] open("/etc/pam.d/other", O_RDONLY|O_LARGEFILE) = 4

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

||||

看懂 SSH 的调用是块难啃的骨头,但是,如果搞懂它你就学会了跟踪。也可以用它去看一个应用程序打开的哪个文件是有用的(“这个配置是从哪里来的?”)。如果你有一个出现错误的进程,你可以跟踪它,然后去看它通过系统调用做了什么?当一些应用程序没有提供适当的错误信息而意外退出时,你可以去检查它是否是一个系统调用失败。你也可以使用过滤器,查看每个调用的次数,等等:

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

123456789

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

|

|

||||

```

|

||||

~/code/x86-os$ strace -T -e trace=recv curl -silent www.google.com. > /dev/nullrecv(3, "HTTP/1.1 200 OK\r\nDate: Wed, 05 N"..., 16384, 0) = 4164 <0.000007>recv(3, "fl a{color:#36c}a:visited{color:"..., 16384, 0) = 2776 <0.000005>recv(3, "adient(top,#4d90fe,#4787ed);filt"..., 16384, 0) = 4164 <0.000007>recv(3, "gbar.up.spd(b,d,1,!0);break;case"..., 16384, 0) = 2776 <0.000006>recv(3, "$),a.i.G(!0)),window.gbar.up.sl("..., 16384, 0) = 1388 <0.000004>recv(3, "margin:0;padding:5px 8px 0 6px;v"..., 16384, 0) = 1388 <0.000007>recv(3, "){window.setTimeout(function(){v"..., 16384, 0) = 1484 <0.000006>

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

||||

我鼓励你去浏览在你的操作系统中的这些工具。使用它们会让你觉得自己像个超人一样强大。

|

||||

|

||||

但是,足够有用的东西,往往要让我们深入到它的设计中。我们可以看到那些用户空间中的应用程序是被严格限制在它自己的虚拟地址空间中,它的虚拟地址空间运行在 Ring 3(非特权模式)中。一般来说,只涉及到计算和内存访问的任务是不需要请求系统调用的。例如,像 [strlen(3)][23] 和 [memcpy(3)][24] 这样的 C 库函数并不需要内核去做什么。这些都是在应用程序内部发生的事。

|

||||

|

||||

一个 C 库函数的 man 页面节上(在圆括号 2 和 3 中)也提供了线索。节 2 是用于系统调用封装,而节 3 包含了其它 C 库函数。但是,正如我们在 printf(3) 中所看到的,一个库函数可以最终产生一个或者多个系统调用。

|

||||

|

||||

如果你对此感到好奇,这里是 [Linux][25] ( [Filippo's list][26])和 [Windows][27] 的全部系统调用列表。它们各自有 ~310 和 ~460 个系统调用。看这些系统调用是非常有趣的,因为,它们代表了软件在现代的计算机上能够做什么。另外,你还可能在这里找到与进程间通讯和性能相关的“宝藏”。这是一个“不懂 Unix 的人注定最终还要重新发明一个蹩脚的 Unix ” 的地方。(译者注:“Those who do not understand Unix are condemned to reinvent it,poorly。”这句话是 [Henry Spencer][35] 的名言,反映了 Unix 的设计哲学,它的一些理念和文化是一种技术发展的必须结果,看似糟糕却无法超越。)

|

||||

|

||||

与 CPU 周期相比,许多系统调用花很长的时间去执行任务,例如,从一个硬盘驱动器中读取内容。在这种情况下,调用进程在底层的工作完成之前一直处于休眠状态。因为,CPUs 运行的非常快,一般的程序都因为 I/O 的限制在它的生命周期的大部分时间处于休眠状态,等待系统的调用。相反,如果你跟踪一个计算密集型任务,你经常会看到没有任何的系统调用参与其中。在这种情况下,[top(1)][29] 将显示大量的 CPU 使用。

|

||||

|

||||

在一个系统调用中的开销可能会是一个问题。例如,固态硬盘比普通硬盘要快很多,但是,操作系统的开销可能比 I/O 操作本身的开销 [更加昂贵][30]。执行大量读写操作的程序可能就是操作系统开销的瓶颈所在。[向量化 I/O][31] 对此有一些帮助。因此要做 [文件的内存映射][32],它允许一个程序仅访问内存就可以读或写磁盘文件。类似的映射也存在于像视频卡这样的地方。最终,经济性俱佳的云计算可能导致内核在用户模式/内核模式的切换消失或者最小化。

|

||||

|

||||

最终,系统调用还有益于系统安全。一是,无论看起来多么模糊的一个二进制程序,你都可以通过观察它的系统调用来检查它的行为。这种方式可能用于去检测恶意程序。例如,我们可以记录一个未知程序的系统调用的策略,并对它的偏差进行报警,或者对程序调用指定一个白名单,这样就可以让漏洞利用变得更加困难。在这个领域,我们有大量的研究,和许多工具,但是没有“杀手级”的解决方案。

|

||||

|

||||

这就是系统调用。很抱歉这篇文章有点长,我希望它对你有用。接下来的时间,我将写更多(短的)文章,也可以在 [RSS][33] 和 [Twitter][34] 关注我。这篇文章献给 glorious Clube Atlético Mineiro。

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via:https://manybutfinite.com/post/system-calls/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Gustavo Duarte][a]

|

||||

译者:[qhwdw](https://github.com/qhwdw)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/about/

|

||||

[1]:https://manybutfinite.com/code/x86-os/pid.c

|

||||

[2]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/anatomy-of-a-program-in-memory

|

||||

[3]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/page-cache-the-affair-between-memory-and-files/

|

||||

[4]:http://linux.die.net/man/2/getpid

|

||||

[5]:https://sourceware.org/git/?p=glibc.git;a=blob;f=sysdeps/unix/sysv/linux/getpid.c;h=937b1d4e113b1cff4a5c698f83d662e130d596af;hb=4c6da7da9fb1f0f94e668e6d2966a4f50a7f0d85#l49

|

||||

[6]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/arch/x86/syscalls/syscall_64.tbl#L48

|

||||

[7]:https://sourceware.org/git/?p=glibc.git;a=blob;f=sysdeps/unix/sysv/linux/x86_64/sysdep.h;h=4a619dafebd180426bf32ab6b6cb0e5e560b718a;hb=4c6da7da9fb1f0f94e668e6d2966a4f50a7f0d85#l139

|

||||

[8]:https://sourceware.org/git/?p=glibc.git;a=blob;f=sysdeps/unix/sysv/linux/x86_64/sysdep.h;h=4a619dafebd180426bf32ab6b6cb0e5e560b718a;hb=4c6da7da9fb1f0f94e668e6d2966a4f50a7f0d85#l179

|

||||

[9]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/cpu-rings-privilege-and-protection

|

||||

[10]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/arch/x86/kernel/entry_64.S#L354-L386

|

||||

[11]:http://lwn.net/Articles/604287/

|

||||

[12]:http://lwn.net/Articles/604515/

|

||||

[13]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/arch/x86/kernel/entry_64.S#L422

|

||||

[14]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/arch/x86/kernel/syscall_64.c#L25

|

||||

[15]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/kernel/sys.c#L800-L809

|

||||

[16]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/kernel/sys.c#L800-L859

|

||||

[17]:http://linux.die.net/man/2/getpid

|

||||

[18]:http://linux.die.net/man/2/syscall

|

||||

[19]:http://linux.die.net/man/1/strace

|

||||

[20]:https://developer.apple.com/library/mac/documentation/Darwin/Reference/ManPages/man1/dtruss.1m.html

|

||||

[21]:http://dtrace.org/blogs/brendan/2011/10/10/top-10-dtrace-scripts-for-mac-os-x/

|

||||

[22]:http://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/sysinternals/bb842062.aspx

|

||||

[23]:http://linux.die.net/man/3/strlen

|

||||

[24]:http://linux.die.net/man/3/memcpy

|

||||

[25]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/arch/x86/syscalls/syscall_64.tbl

|

||||

[26]:https://filippo.io/linux-syscall-table/

|

||||

[27]:http://j00ru.vexillium.org/ntapi/

|

||||

[28]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/what-your-computer-does-while-you-wait/

|

||||

[29]:http://linux.die.net/man/1/top

|

||||

[30]:http://danluu.com/clwb-pcommit/

|

||||

[31]:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vectored_I/O

|

||||

[32]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/page-cache-the-affair-between-memory-and-files/

|

||||

[33]:http://feeds.feedburner.com/GustavoDuarte

|

||||

[34]:http://twitter.com/food4hackers

|

||||

[35]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Spencer

|

||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user