mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-02-25 00:50:15 +08:00

commit

dd1c55a46f

@ -1,234 +0,0 @@

|

||||

#Translating by qhwdw [Closures, Objects, and the Fauna of the Heap][1]

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The last post in this series looks at closures, objects, and other creatures roaming beyond the stack. Much of what we'll see is language neutral, but I'll focus on JavaScript with a dash of C. Let's start with a simple C program that reads a song and a band name and outputs them back to the user:

|

||||

|

||||

stackFolly.c [download][2]

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

#include <stdio.h>

|

||||

#include <string.h>

|

||||

|

||||

char *read()

|

||||

{

|

||||

char data[64];

|

||||

fgets(data, 64, stdin);

|

||||

return data;

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

|

||||

{

|

||||

char *song, *band;

|

||||

|

||||

puts("Enter song, then band:");

|

||||

song = read();

|

||||

band = read();

|

||||

|

||||

printf("\n%sby %s", song, band);

|

||||

return 0;

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

If you run this gem, here's what you get (=> denotes program output):

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

./stackFolly

|

||||

=> Enter song, then band:

|

||||

The Past is a Grotesque Animal

|

||||

of Montreal

|

||||

|

||||

=> ?ǿontreal

|

||||

=> by ?ǿontreal

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Ayeee! Where did things go so wrong? (Said every C beginner, ever.)

|

||||

|

||||

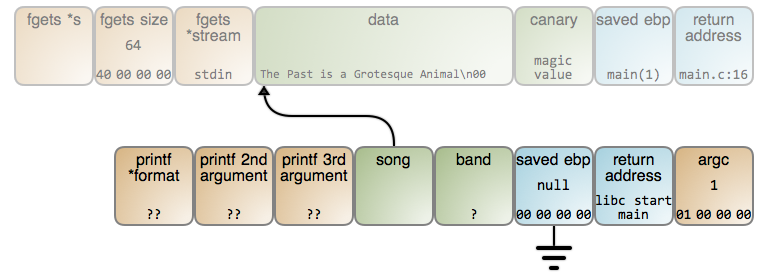

It turns out that the contents of a function's stack variables are only valid while the stack frame is active, that is, until the function returns. Upon return, the memory used by the stack frame is [deemed free][3] and liable to be overwritten in the next function call.

|

||||

|

||||

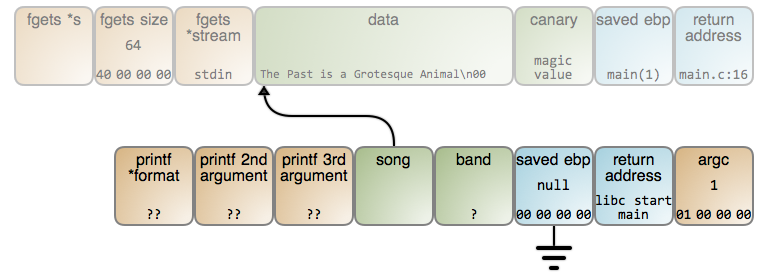

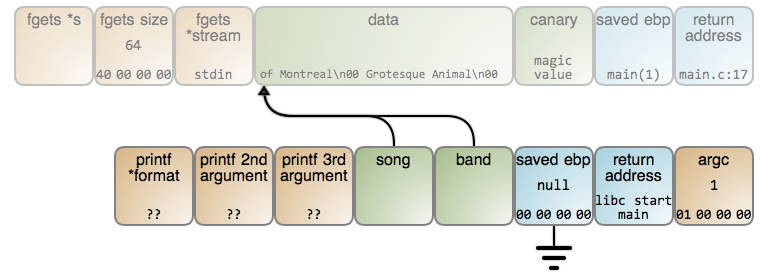

Below is exactly what happens in this case. The diagrams now have image maps, so you can click on a piece of data to see the relevant gdb output (gdb commands are [here][4]). As soon as read() is done with the song name, the stack is thus:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

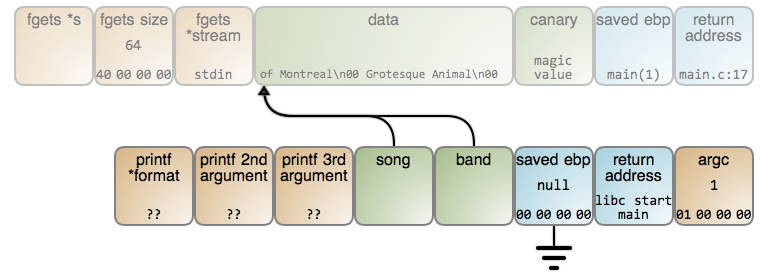

At this point, the song variable actually points to the song name. Sadly, the memory storing that string is ready to be reused by the stack frame of whatever function is called next. In this case, read() is called again, with the same stack frame layout, so the result is this:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

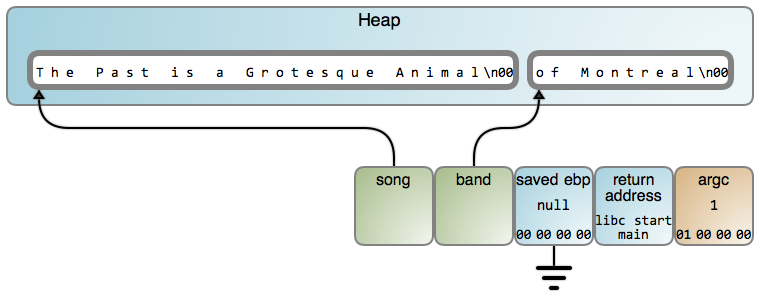

The band name is read into the same memory location and overwrites the previously stored song name. band and song end up pointing to the exact same spot. Finally, we didn't even get "of Montreal" output correctly. Can you guess why?

|

||||

|

||||

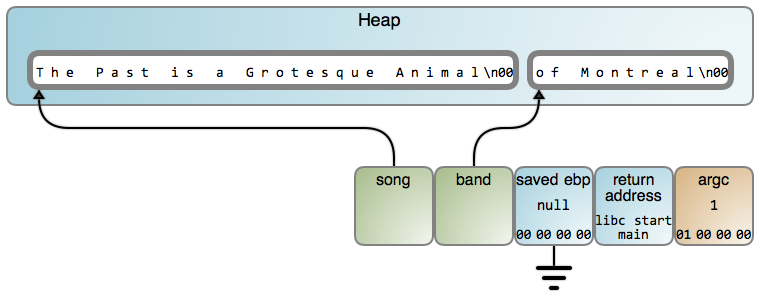

And so it happens that the stack, for all its usefulness, has this serious limitation. It cannot be used by a function to store data that needs to outlive the function's execution. You must resort to the [heap][5] and say goodbye to the hot caches, deterministic instantaneous operations, and easily computed offsets. On the plus side, it [works][6]:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The price is you must now remember to free() memory or take a performance hit on a garbage collector, which finds unused heap objects and frees them. That's the fundamental tradeoff between stack and heap: performance vs. flexibility.

|

||||

|

||||

Most languages' virtual machines take a middle road that mirrors what C programmers do. The stack is used for value types, things like integers, floats and booleans. These are stored directly in local variables and object fields as a sequence of bytes specifying a value (like argc above). In contrast, heap inhabitants are reference types such as strings and [objects][7]. Variables and fields contain a memory address that references these objects, like song and band above.

|

||||

|

||||

Consider this JavaScript function:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

function fn()

|

||||

{

|

||||

var a = 10;

|

||||

var b = { name: 'foo', n: 10 };

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

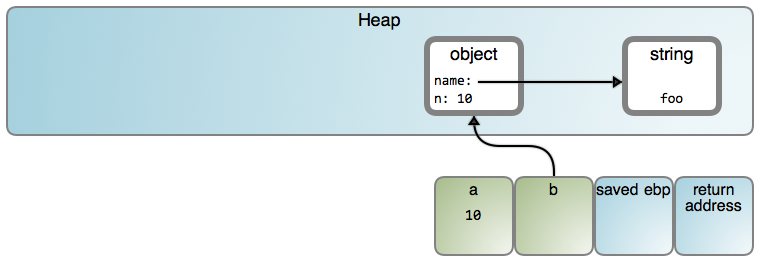

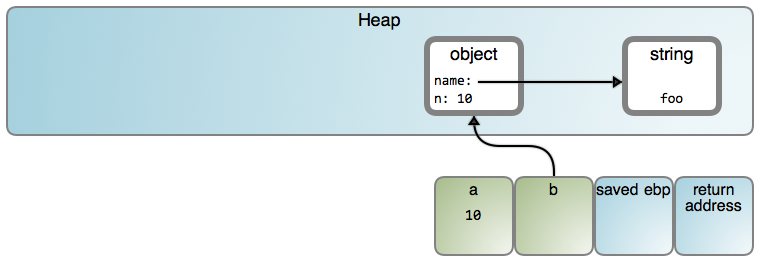

This might produce the following:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

I say "might" because specific behaviors depend heavily on implementation. This post takes a V8-centric approach with many diagram shapes linking to relevant source code. In V8, only [small integers][8] are [stored as values][9]. Also, from now on I'll show strings directly in objects to reduce visual noise, but keep in mind they exist separately in the heap, as shown above.

|

||||

|

||||

Now let's take a look at closures, which are simple but get weirdly hyped up and mythologized. Take a trivial JS function:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

function add(a, b)

|

||||

{

|

||||

var c = a + b;

|

||||

return c;

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This function defines a lexical scope, a happy little kingdom where the names a, b, and c have precise meanings. They are the two parameters and one local variable declared by the function. The program might use those same names elsewhere, but within add that's what they refer to. And while lexical scope is a fancy term, it aligns well with our intuitive understanding: after all, we can quite literally see the bloody thing, much as a lexer does, as a textual block in the program's source.

|

||||

|

||||

Having seen stack frames in action, it's easy to imagine an implementation for this name specificity. Within add, these names refer to stack locations private to each running instance of the function. That's in fact how it often plays out in a VM.

|

||||

|

||||

So let's nest two lexical scopes:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

function makeGreeter()

|

||||

{

|

||||

return function hi(name){

|

||||

console.log('hi, ' + name);

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

var hi = makeGreeter();

|

||||

hi('dear reader'); // prints "hi, dear reader"

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

That's more interesting. Function hi is built at runtime within makeGreeter. It has its own lexical scope, where name is an argument on the stack, but visually it sure looks like it can access its parent's lexical scope as well, which it can. Let's take advantage of that:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

function makeGreeter(greeting)

|

||||

{

|

||||

return function greet(name){

|

||||

console.log(greeting + ', ' + name);

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

var heya = makeGreeter('HEYA');

|

||||

heya('dear reader'); // prints "HEYA, dear reader"

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

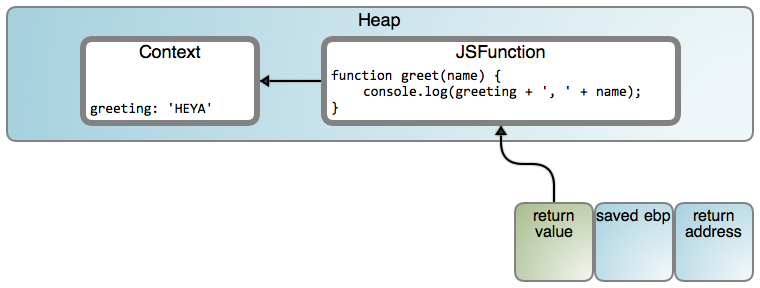

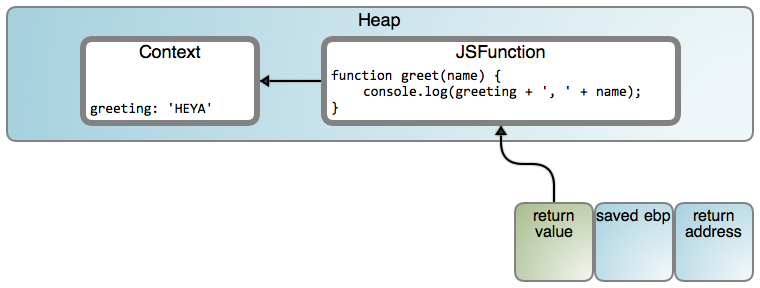

A little strange, but pretty cool. There's something about it though that violates our intuition: greeting sure looks like a stack variable, the kind that should be dead after makeGreeter() returns. And yet, since greet() keeps working, something funny is going on. Enter the closure:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The VM allocated an object to store the parent variable used by the inner greet(). It's as if makeGreeter's lexical scope had been closed over at that moment, crystallized into a heap object for as long as needed (in this case, the lifetime of the returned function). Hence the name closure, which makes a lot of sense when you see it that way. If more parent variables had been used (or captured), the Context object would have more properties, one per captured variable. Naturally, the code emitted for greet() knows to read greeting from the Context object, rather than expect it on the stack.

|

||||

|

||||

Here's a fuller example:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

function makeGreeter(greetings)

|

||||

{

|

||||

var count = 0;

|

||||

var greeter = {};

|

||||

|

||||

for (var i = 0; i < greetings.length; i++) {

|

||||

var greeting = greetings[i];

|

||||

|

||||

greeter[greeting] = function(name){

|

||||

count++;

|

||||

console.log(greeting + ', ' + name);

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

greeter.count = function(){return count;}

|

||||

|

||||

return greeter;

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

var greeter = makeGreeter(["hi", "hello","howdy"])

|

||||

greeter.hi('poppet');//prints "howdy, poppet"

|

||||

greeter.hello('darling');// prints "howdy, darling"

|

||||

greeter.count(); // returns 2

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

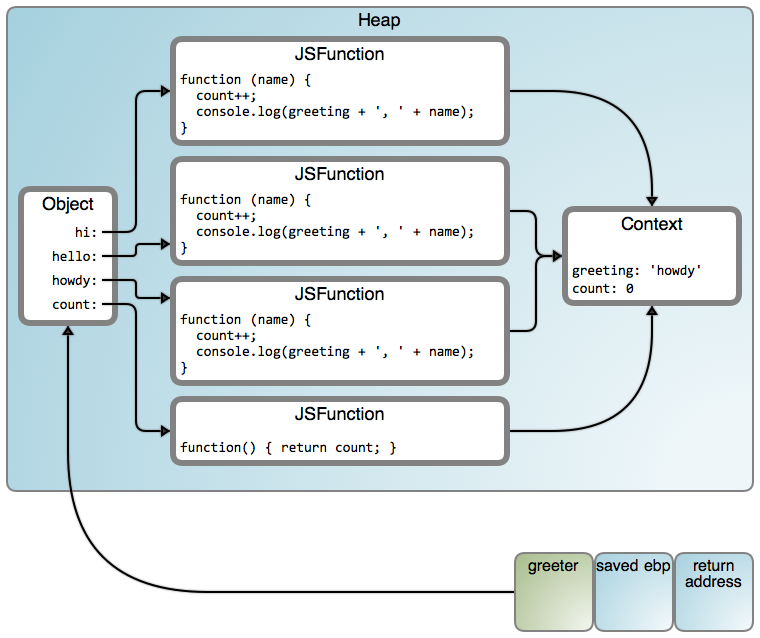

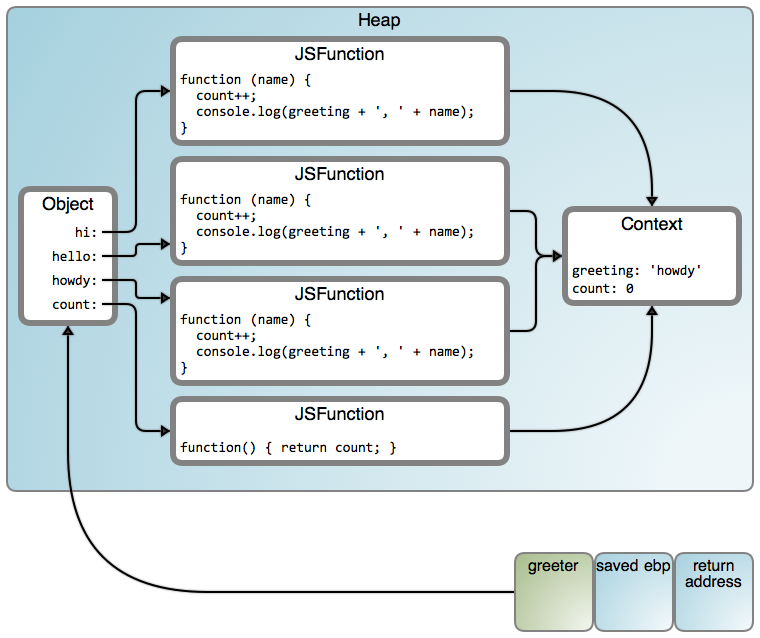

Well... count() works, but our greeter is stuck in howdy. Can you tell why? What we're doing with count is a clue: even though the lexical scope is closed over into a heap object, the values taken by the variables (or object properties) can still be changed. Here's what we have:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

There is one common context shared by all functions. That's why count works. But the greeting is also being shared, and it was set to the last value iterated over, "howdy" in this case. That's a pretty common error, and the easiest way to avoid it is to introduce a function call to take the closed-over variable as an argument. In CoffeeScript, the [do][10] command provides an easy way to do so. Here's a simple solution for our greeter:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

function makeGreeter(greetings)

|

||||

{

|

||||

var count = 0;

|

||||

var greeter = {};

|

||||

|

||||

greetings.forEach(function(greeting){

|

||||

greeter[greeting] = function(name){

|

||||

count++;

|

||||

console.log(greeting + ', ' + name);

|

||||

}

|

||||

});

|

||||

|

||||

greeter.count = function(){return count;}

|

||||

|

||||

return greeter;

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

var greeter = makeGreeter(["hi", "hello", "howdy"])

|

||||

greeter.hi('poppet'); // prints "hi, poppet"

|

||||

greeter.hello('darling'); // prints "hello, darling"

|

||||

greeter.count(); // returns 2

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

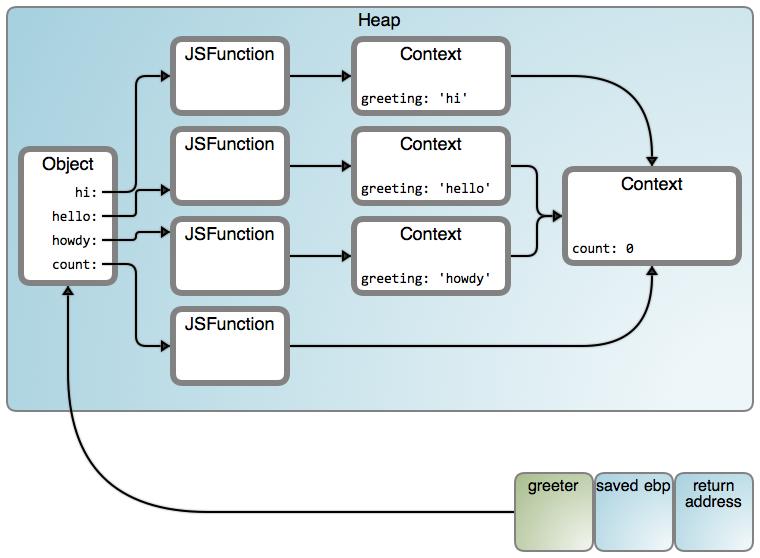

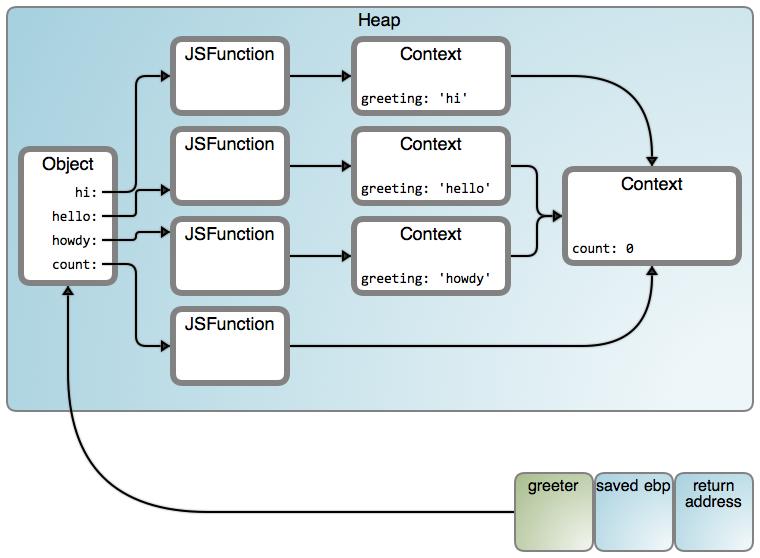

It now works, and the result becomes:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

That's a lot of arrows! But here's the interesting feature: in our code, we closed over two nested lexical contexts, and sure enough we get two linked Context objects in the heap. You could nest and close over many lexical contexts, Russian-doll style, and you end up with essentially a linked list of all these Context objects.

|

||||

|

||||

Of course, just as you can implement TCP over carrier pigeons, there are many ways to implement these language features. For example, the ES6 spec defines [lexical environments][11] as consisting of an [environment record][12] (roughly, the local identifiers within a block) plus a link to an outer environment record, allowing the nesting we have seen. The logical rules are nailed by the spec (one hopes), but it's up to the implementation to translate them into bits and bytes.

|

||||

|

||||

You can also inspect the assembly code produced by V8 for specific cases. [Vyacheslav Egorov][13] has great posts and explains this process along with V8 [closure internals][14] in detail. I've only started studying V8, so pointers and corrections are welcome. If you know C#, inspecting the IL code emitted for closures is enlightening - you will see the analog of V8 Contexts explicitly defined and instantiated.

|

||||

|

||||

Closures are powerful beasts. They provide a succinct way to hide information from a caller while sharing it among a set of functions. I love that they truly hide your data: unlike object fields, callers cannot access or even see closed-over variables. Keeps the interface cleaner and safer.

|

||||

|

||||

But they're no silver bullet. Sometimes an object nut and a closure fanatic will argue endlessly about their relative merits. Like most tech discussions, it's often more about ego than real tradeoffs. At any rate, this [epic koan][15] by Anton van Straaten settles the issue:

|

||||

|

||||

> The venerable master Qc Na was walking with his student, Anton. Hoping to prompt the master into a discussion, Anton said "Master, I have heard that objects are a very good thing - is this true?" Qc Na looked pityingly at his student and replied, "Foolish pupil - objects are merely a poor man's closures." Chastised, Anton took his leave from his master and returned to his cell, intent on studying closures. He carefully read the entire "Lambda: The Ultimate..." series of papers and its cousins, and implemented a small Scheme interpreter with a closure-based object system. He learned much, and looked forward to informing his master of his progress. On his next walk with Qc Na, Anton attempted to impress his master by saying "Master, I have diligently studied the matter, and now understand that objects are truly a poor man's closures." Qc Na responded by hitting Anton with his stick, saying "When will you learn? Closures are a poor man's object." At that moment, Anton became enlightened. Anton van StraatenWhat's so cool about Scheme?

|

||||

|

||||

And that closes our stack series. In the future I plan to cover other language implementation topics like object binding and vtables. But the call of the kernel is strong, so there's an OS post coming out tomorrow. I invite you to [subscribe][16] and [follow me][17].

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via:https://manybutfinite.com/post/closures-objects-heap/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Gustavo Duarte][a]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/about/

|

||||

[1]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/closures-objects-heap/

|

||||

[2]:https://manybutfinite.com/code/x86-stack/stackFolly.c

|

||||

[3]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/epilogues-canaries-buffer-overflows/

|

||||

[4]:https://github.com/gduarte/blog/blob/master/code/x86-stack/stackFolly-gdb-commands.txt

|

||||

[5]:https://github.com/gduarte/blog/blob/master/code/x86-stack/readIntoHeap.c

|

||||

[6]:https://github.com/gduarte/blog/blob/master/code/x86-stack/readIntoHeap-gdb-output.txt#L47

|

||||

[7]:https://code.google.com/p/v8/source/browse/trunk/src/objects.h#37

|

||||

[8]:https://code.google.com/p/v8/source/browse/trunk/src/objects.h#1264

|

||||

[9]:https://code.google.com/p/v8/source/browse/trunk/src/objects.h#148

|

||||

[10]:http://coffeescript.org/#loops

|

||||

[11]:http://people.mozilla.org/~jorendorff/es6-draft.html#sec-lexical-environments

|

||||

[12]:http://people.mozilla.org/~jorendorff/es6-draft.html#sec-environment-records

|

||||

[13]:http://mrale.ph

|

||||

[14]:http://mrale.ph/blog/2012/09/23/grokking-v8-closures-for-fun.html

|

||||

[15]:http://people.csail.mit.edu/gregs/ll1-discuss-archive-html/msg03277.html

|

||||

[16]:https://manybutfinite.com/feed.xml

|

||||

[17]:http://twitter.com/manybutfinite

|

||||

@ -0,0 +1,234 @@

|

||||

#[闭包,对象,以及堆“族”][1]

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

在上篇文章中我们提到了闭包、对象、以及栈外的其它东西。我们学习的大部分内容都是与特定编程语言无关的元素,但是,我主要还是专注于 JavaScript,以及一些 C。让我们以一个简单的 C 程序开始,它的功能是读取一首歌曲和乐队名字,然后将它们输出给用户:

|

||||

|

||||

stackFolly.c [下载][2]

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

#include <stdio.h>

|

||||

#include <string.h>

|

||||

|

||||

char *read()

|

||||

{

|

||||

char data[64];

|

||||

fgets(data, 64, stdin);

|

||||

return data;

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

|

||||

{

|

||||

char *song, *band;

|

||||

|

||||

puts("Enter song, then band:");

|

||||

song = read();

|

||||

band = read();

|

||||

|

||||

printf("\n%sby %s", song, band);

|

||||

return 0;

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

如果你运行这个程序,你会得到什么?(=> 表示程序输出):

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

./stackFolly

|

||||

=> Enter song, then band:

|

||||

The Past is a Grotesque Animal

|

||||

of Montreal

|

||||

|

||||

=> ?ǿontreal

|

||||

=> by ?ǿontreal

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

(曾经的 C 新手说)发生了错误?

|

||||

|

||||

事实证明,函数的栈变量的内容仅在栈帧活动期间才是可用的,也就是说,仅在函数返回之前。在上面的返回中,被栈帧使用的内存 [被认为是可用的][3],并且在下一个函数调用中可以被覆写。

|

||||

|

||||

下面的图展示了这种情况下究竟发生了什么。这个图现在有一个镜像映射,因此,你可以点击一个数据片断去看一下相关的 GDB 输出(GDB 命令在 [这里][4])。只要 `read()` 读取了歌曲的名字,栈将是这个样子:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

在这个时候,这个 `song` 变量立即指向到歌曲的名字。不幸的是,存储字符串的内存位置准备被下次调用的任意函数的栈帧重用。在这种情况下,`read()` 再次被调用,而且使用的是同一个位置的栈帧,因此,结果变成下图的样子:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

乐队名字被读入到相同的内存位置,并且覆盖了前面存储的歌曲名字。`band` 和 `song` 最终都准确指向到相同点。最后,我们甚至都不能得到 “of Montreal”(译者注:一个欧美乐队的名字) 的正确输出。你能猜到是为什么吗?

|

||||

|

||||

因此,即使栈很有用,但也有很重要的限制。它不能被一个函数用于去存储比该函数的运行周期还要长的数据。你必须将它交给 [堆][5],然后与热点缓存、明确的瞬时操作、以及频繁计算的偏移等内容道别。有利的一面是,它是[工作][6] 的:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

这个代价是你必须记得去`free()` 内存,或者由一个垃圾回收机制花费一些性能来随机回收,垃圾回收将去找到未使用的堆对象,然后去回收它们。那就是栈和堆之间在本质上的权衡:性能 vs. 灵活性。

|

||||

|

||||

大多数编程语言的虚拟机都有一个中间层用来做一个 C 程序员该做的一些事情。栈被用于**值类型**,比如,整数、浮点数、以及布尔型。这些都按特定值(像上面的 `argc` )的字节顺序被直接保存在本地变量和对象字段中。相比之下,堆被用于**引用类型**,比如,字符串和 [对象][7]。 变量和字段包含一个引用到这个对象的内存地址,像上面的 `song` 和 `band`。

|

||||

|

||||

参考这个 JavaScript 函数:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

function fn()

|

||||

{

|

||||

var a = 10;

|

||||

var b = { name: 'foo', n: 10 };

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

它可能的结果如下:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

我之所以说“可能”的原因是,特定的行为高度依赖于实现。这篇文章使用的许多图形是以一个 V8 为中心的方法,这些图形都链接到相关的源代码。在 V8 中,仅 [小整数][8] 是 [以值的方式保存][9]。因此,从现在开始,我将在对象中直接以字符串去展示,以避免引起混乱,但是,请记住,正如上图所示的那样,它们在堆中是分开保存的。

|

||||

|

||||

现在,我们来看一下闭包,它其实很简单,但是由于我们将它宣传的过于夸张,以致于有点神化了。先看一个简单的 JS 函数:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

function add(a, b)

|

||||

{

|

||||

var c = a + b;

|

||||

return c;

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

这个函数定义了一个词法域(lexical scope),它是一个快乐的小王国,在这里它的名字 a,b,c 是有明确意义的。它有两个参数和由函数声明的一个本地变量。程序也可以在别的地方使用相同的名字,但是在 `add` 内部它们所引用的内容是明确的。尽管词法域是一个很好的术语,它符合我们直观上的理解:毕竟,我们从字面意义上看,我们可以像词法分析器一样,把它看作在源代码中的一个文本块。

|

||||

|

||||

在看到栈帧的操作之后,很容易想像出这个名称的具体实现。在 `add` 内部,这些名字引用到函数的每个运行实例中私有的栈的位置。这种情况在一个虚拟机中经常发生。

|

||||

|

||||

现在,我们来嵌套两个词法域:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

function makeGreeter()

|

||||

{

|

||||

return function hi(name){

|

||||

console.log('hi, ' + name);

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

var hi = makeGreeter();

|

||||

hi('dear reader'); // prints "hi, dear reader"

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

那样更有趣。函数 `hi` 在函数 `makeGreeter` 运行的时候被构建在它内部。它有它自己的词法域,`name` 在这个地方是一个栈上的参数,但是,它似乎也可以访问父级的词法域,它可以那样做。我们来看一下那样做的好处:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

function makeGreeter(greeting)

|

||||

{

|

||||

return function greet(name){

|

||||

console.log(greeting + ', ' + name);

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

var heya = makeGreeter('HEYA');

|

||||

heya('dear reader'); // prints "HEYA, dear reader"

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

虽然有点不习惯,但是很酷。即便这样违背了我们的直觉:`greeting` 确实看起来像一个栈变量,这种类型应该在 `makeGreeter()` 返回后消失。可是因为 `greet()` 一直保持工作,出现了一些奇怪的事情。进入闭包:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

虚拟机分配一个对象去保存被里面的 `greet()` 使用的父级变量。它就好像是 `makeGreeter` 的词法作用域在那个时刻被关闭了,一旦需要时被具体化到一个堆对象(在这个案例中,是指返回的函数的生命周期)。因此叫做闭包,当你这样去想它的时候,它的名字就有意义了。如果使用(或者捕获)了更多的父级变量,对象内容将有更多的属性,每个捕获的变量有一个。当然,发送到 `greet()` 的代码知道从对象内容中去读取问候语,而不是从栈上。

|

||||

|

||||

这是完整的示例:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

function makeGreeter(greetings)

|

||||

{

|

||||

var count = 0;

|

||||

var greeter = {};

|

||||

|

||||

for (var i = 0; i < greetings.length; i++) {

|

||||

var greeting = greetings[i];

|

||||

|

||||

greeter[greeting] = function(name){

|

||||

count++;

|

||||

console.log(greeting + ', ' + name);

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

greeter.count = function(){return count;}

|

||||

|

||||

return greeter;

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

var greeter = makeGreeter(["hi", "hello","howdy"])

|

||||

greeter.hi('poppet');//prints "howdy, poppet"

|

||||

greeter.hello('darling');// prints "howdy, darling"

|

||||

greeter.count(); // returns 2

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

是的,`count()` 在工作,但是我们的 `greeter` 是在 `howdy` 中的栈上。你能告诉我为什么吗?我们使用 `count` 是一条线索:尽管词法域进入一个堆对象中被关闭,但是变量(或者对象属性)带的值仍然可能被改变。下图是我们拥有的内容:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

这是一个被所有函数共享的公共内容。那就是为什么 `count` 工作的原因。但是,`greeting` 也是被共享的,并且它被设置为迭代结束后的最后一个值,在这个案例中是“howdy”。这是一个很常见的一般错误,避免它的简单方法是,引用一个函数调用,以闭包变量作为一个参数。在 CoffeeScript 中, [do][10] 命令提供了一个实现这种目的的简单方式。下面是对我们的 `greeter` 的一个简单的解决方案:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

function makeGreeter(greetings)

|

||||

{

|

||||

var count = 0;

|

||||

var greeter = {};

|

||||

|

||||

greetings.forEach(function(greeting){

|

||||

greeter[greeting] = function(name){

|

||||

count++;

|

||||

console.log(greeting + ', ' + name);

|

||||

}

|

||||

});

|

||||

|

||||

greeter.count = function(){return count;}

|

||||

|

||||

return greeter;

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

var greeter = makeGreeter(["hi", "hello", "howdy"])

|

||||

greeter.hi('poppet'); // prints "hi, poppet"

|

||||

greeter.hello('darling'); // prints "hello, darling"

|

||||

greeter.count(); // returns 2

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

它现在是工作的,并且结果将变成下图所示:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

这里有许多箭头!在这里我们感兴趣的特性是:在我们的代码中,我们闭包了两个嵌套的词法内容,并且完全可以确保我们得到了两个链接到堆上的对象内容。你可以嵌套并且闭包任何词法内容、“俄罗斯套娃”类型、并且最终从本质上说你使用的是所有那些对象内容的一个链表。

|

||||

|

||||

当然,就像受信鸽携带信息启发实现了 TCP 一样,去实现这些编程语言的特性也有很多种方法。例如,ES6 规范定义了 [词法环境][11] 作为 [环境记录][12]( 大致相当于在一个块内的本地标识)的组成部分,加上一个链接到外部环境的记录,这样就允许我们看到的嵌套。逻辑规则是由规范(一个希望)所确定的,但是其实现取决于将它们变成比特和字节的转换。

|

||||

|

||||

你也可以检查具体案例中由 V8 产生的汇编代码。[Vyacheslav Egorov][13] 有一篇很好的文章,它在细节中使用 V8 的 [闭包内部构件][14] 解释了这一过程。我刚开始学习 V8,因此,欢迎指教。如果你熟悉 C#,检查闭包产生的中间代码将会很受启发 - 你将看到显式定义的 V8 内容和实例化的模拟。

|

||||

|

||||

闭包是个强大的“家伙”。它在被一组函数共享期间,提供了一个简单的方式去隐藏来自调用者的信息。我喜欢它们真正地隐藏你的数据:不像对象字段,调用者并不能访问或者甚至是看到闭包变量。保持接口清晰而安全。

|

||||

|

||||

但是,它们并不是“银弹”(译者注:意指极为有效的解决方案,或者寄予厚望的新技术)。有时候一个对象的拥护者和一个闭包的狂热者会无休止地争论它们的优点。就像大多数的技术讨论一样,他们通常更关注的是自尊而不是真正的权衡。不管怎样,Anton van Straaten 的这篇 [史诗级的公案][15] 解决了这个问题:

|

||||

|

||||

> 德高望重的老师 Qc Na 和它的学生 Anton 一起散步。Anton 希望将老师引入到一个讨论中,Anton 说:“老师,我听说对象是一个非常好的东西,是这样的吗?Qc Na 同情地看了一眼,责备它的学生说:“可怜的孩子 - 对象不过是穷人的闭包。” Anton 待它的老师走了之后,回到他的房间,专心学习闭包。他认真地阅读了完整的 “Lambda:The Ultimate…" 系列文章和它的相关资料,并使用一个基于闭包的对象系统实现了一个小的架构解释器。他学到了很多的东西,并期待告诉老师他的进步。在又一次和 Qc Na 散步时,Anton 尝试给老师留下一个好的印象,说“老师,我仔细研究了这个问题,并且,现在理解了对象真的是穷人的闭包。”Qc Na 用它的手杖打了一下 Anton 说:“你什么时候才能明白?闭包是穷人的对象。”在那个时候,Anton 顿悟了。Anton van Straaten 说:“原来架构这么酷啊?”

|

||||

|

||||

探秘“栈”系列文章到此结束了。后面我将计划去写一些其它的编程语言实现的主题,像对象绑定和虚表。但是,内核调用是很强大的,因此,明天将发布一篇操作系统的文章。我邀请你 [订阅][16] 并 [关注我][17]。

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via:https://manybutfinite.com/post/closures-objects-heap/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Gustavo Duarte][a]

|

||||

译者:[qhwdw](https://github.com/qhwdw)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/about/

|

||||

[1]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/closures-objects-heap/

|

||||

[2]:https://manybutfinite.com/code/x86-stack/stackFolly.c

|

||||

[3]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/epilogues-canaries-buffer-overflows/

|

||||

[4]:https://github.com/gduarte/blog/blob/master/code/x86-stack/stackFolly-gdb-commands.txt

|

||||

[5]:https://github.com/gduarte/blog/blob/master/code/x86-stack/readIntoHeap.c

|

||||

[6]:https://github.com/gduarte/blog/blob/master/code/x86-stack/readIntoHeap-gdb-output.txt#L47

|

||||

[7]:https://code.google.com/p/v8/source/browse/trunk/src/objects.h#37

|

||||

[8]:https://code.google.com/p/v8/source/browse/trunk/src/objects.h#1264

|

||||

[9]:https://code.google.com/p/v8/source/browse/trunk/src/objects.h#148

|

||||

[10]:http://coffeescript.org/#loops

|

||||

[11]:http://people.mozilla.org/~jorendorff/es6-draft.html#sec-lexical-environments

|

||||

[12]:http://people.mozilla.org/~jorendorff/es6-draft.html#sec-environment-records

|

||||

[13]:http://mrale.ph

|

||||

[14]:http://mrale.ph/blog/2012/09/23/grokking-v8-closures-for-fun.html

|

||||

[15]:http://people.csail.mit.edu/gregs/ll1-discuss-archive-html/msg03277.html

|

||||

[16]:https://manybutfinite.com/feed.xml

|

||||

[17]:http://twitter.com/manybutfinite

|

||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user