mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-03-27 02:30:10 +08:00

20150818-1 选题 LFCS 专题 6-10 共十篇 完结

This commit is contained in:

parent

40cbb17f9e

commit

dc7c041b3c

@ -0,0 +1,315 @@

|

||||

Part 10 - LFCS: Understanding & Learning Basic Shell Scripting and Linux Filesystem Troubleshooting

|

||||

================================================================================

|

||||

The Linux Foundation launched the LFCS certification (Linux Foundation Certified Sysadmin), a brand new initiative whose purpose is to allow individuals everywhere (and anywhere) to get certified in basic to intermediate operational support for Linux systems, which includes supporting running systems and services, along with overall monitoring and analysis, plus smart decision-making when it comes to raising issues to upper support teams.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Linux Foundation Certified Sysadmin – Part 10

|

||||

|

||||

Check out the following video that guides you an introduction to the Linux Foundation Certification Program.

|

||||

|

||||

注:youtube 视频

|

||||

|

||||

<iframe width="720" height="405" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen="allowfullscreen" src="//www.youtube.com/embed/Y29qZ71Kicg"></iframe>

|

||||

|

||||

This is the last article (Part 10) of the present 10-tutorial long series. In this article we will focus on basic shell scripting and troubleshooting Linux file systems. Both topics are required for the LFCS certification exam.

|

||||

|

||||

### Understanding Terminals and Shells ###

|

||||

|

||||

Let’s clarify a few concepts first.

|

||||

|

||||

- A shell is a program that takes commands and gives them to the operating system to be executed.

|

||||

- A terminal is a program that allows us as end users to interact with the shell. One example of a terminal is GNOME terminal, as shown in the below image.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Gnome Terminal

|

||||

|

||||

When we first start a shell, it presents a command prompt (also known as the command line), which tells us that the shell is ready to start accepting commands from its standard input device, which is usually the keyboard.

|

||||

|

||||

You may want to refer to another article in this series ([Use Command to Create, Edit, and Manipulate files – Part 1][1]) to review some useful commands.

|

||||

|

||||

Linux provides a range of options for shells, the following being the most common:

|

||||

|

||||

**bash Shell**

|

||||

|

||||

Bash stands for Bourne Again SHell and is the GNU Project’s default shell. It incorporates useful features from the Korn shell (ksh) and C shell (csh), offering several improvements at the same time. This is the default shell used by the distributions covered in the LFCS certification, and it is the shell that we will use in this tutorial.

|

||||

|

||||

**sh Shell**

|

||||

|

||||

The Bourne SHell is the oldest shell and therefore has been the default shell of many UNIX-like operating systems for many years.

|

||||

ksh Shell

|

||||

|

||||

The Korn SHell is a Unix shell which was developed by David Korn at Bell Labs in the early 1980s. It is backward-compatible with the Bourne shell and includes many features of the C shell.

|

||||

|

||||

A shell script is nothing more and nothing less than a text file turned into an executable program that combines commands that are executed by the shell one after another.

|

||||

|

||||

### Basic Shell Scripting ###

|

||||

|

||||

As mentioned earlier, a shell script is born as a plain text file. Thus, can be created and edited using our preferred text editor. You may want to consider using vi/m (refer to [Usage of vi Editor – Part 2][2] of this series), which features syntax highlighting for your convenience.

|

||||

|

||||

Type the following command to create a file named myscript.sh and press Enter.

|

||||

|

||||

# vim myscript.sh

|

||||

|

||||

The very first line of a shell script must be as follows (also known as a shebang).

|

||||

|

||||

#!/bin/bash

|

||||

|

||||

It “tells” the operating system the name of the interpreter that should be used to run the text that follows.

|

||||

|

||||

Now it’s time to add our commands. We can clarify the purpose of each command, or the entire script, by adding comments as well. Note that the shell ignores those lines beginning with a pound sign # (explanatory comments).

|

||||

|

||||

#!/bin/bash

|

||||

echo This is Part 10 of the 10-article series about the LFCS certification

|

||||

echo Today is $(date +%Y-%m-%d)

|

||||

|

||||

Once the script has been written and saved, we need to make it executable.

|

||||

|

||||

# chmod 755 myscript.sh

|

||||

|

||||

Before running our script, we need to say a few words about the $PATH environment variable. If we run,

|

||||

|

||||

echo $PATH

|

||||

|

||||

from the command line, we will see the contents of $PATH: a colon-separated list of directories that are searched when we enter the name of a executable program. It is called an environment variable because it is part of the shell environment – a set of information that becomes available for the shell and its child processes when the shell is first started.

|

||||

|

||||

When we type a command and press Enter, the shell searches in all the directories listed in the $PATH variable and executes the first instance that is found. Let’s see an example,

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Environment Variables

|

||||

|

||||

If there are two executable files with the same name, one in /usr/local/bin and another in /usr/bin, the one in the first directory will be executed first, whereas the other will be disregarded.

|

||||

|

||||

If we haven’t saved our script inside one of the directories listed in the $PATH variable, we need to append ./ to the file name in order to execute it. Otherwise, we can run it just as we would do with a regular command.

|

||||

|

||||

# pwd

|

||||

# ./myscript.sh

|

||||

# cp myscript.sh ../bin

|

||||

# cd ../bin

|

||||

# pwd

|

||||

# myscript.sh

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Execute Script

|

||||

|

||||

#### Conditionals ####

|

||||

|

||||

Whenever you need to specify different courses of action to be taken in a shell script, as result of the success or failure of a command, you will use the if construct to define such conditions. Its basic syntax is:

|

||||

|

||||

if CONDITION; then

|

||||

COMMANDS;

|

||||

else

|

||||

OTHER-COMMANDS

|

||||

fi

|

||||

|

||||

Where CONDITION can be one of the following (only the most frequent conditions are cited here) and evaluates to true when:

|

||||

|

||||

- [ -a file ] → file exists.

|

||||

- [ -d file ] → file exists and is a directory.

|

||||

- [ -f file ] →file exists and is a regular file.

|

||||

- [ -u file ] →file exists and its SUID (set user ID) bit is set.

|

||||

- [ -g file ] →file exists and its SGID bit is set.

|

||||

- [ -k file ] →file exists and its sticky bit is set.

|

||||

- [ -r file ] →file exists and is readable.

|

||||

- [ -s file ]→ file exists and is not empty.

|

||||

- [ -w file ]→file exists and is writable.

|

||||

- [ -x file ] is true if file exists and is executable.

|

||||

- [ string1 = string2 ] → the strings are equal.

|

||||

- [ string1 != string2 ] →the strings are not equal.

|

||||

|

||||

[ int1 op int2 ] should be part of the preceding list, while the items that follow (for example, -eq –> is true if int1 is equal to int2.) should be a “children” list of [ int1 op int2 ] where op is one of the following comparison operators.

|

||||

|

||||

- -eq –> is true if int1 is equal to int2.

|

||||

- -ne –> true if int1 is not equal to int2.

|

||||

- -lt –> true if int1 is less than int2.

|

||||

- -le –> true if int1 is less than or equal to int2.

|

||||

- -gt –> true if int1 is greater than int2.

|

||||

- -ge –> true if int1 is greater than or equal to int2.

|

||||

|

||||

#### For Loops ####

|

||||

|

||||

This loop allows to execute one or more commands for each value in a list of values. Its basic syntax is:

|

||||

|

||||

for item in SEQUENCE; do

|

||||

COMMANDS;

|

||||

done

|

||||

|

||||

Where item is a generic variable that represents each value in SEQUENCE during each iteration.

|

||||

|

||||

#### While Loops ####

|

||||

|

||||

This loop allows to execute a series of repetitive commands as long as the control command executes with an exit status equal to zero (successfully). Its basic syntax is:

|

||||

|

||||

while EVALUATION_COMMAND; do

|

||||

EXECUTE_COMMANDS;

|

||||

done

|

||||

|

||||

Where EVALUATION_COMMAND can be any command(s) that can exit with a success (0) or failure (other than 0) status, and EXECUTE_COMMANDS can be any program, script or shell construct, including other nested loops.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Putting It All Together ####

|

||||

|

||||

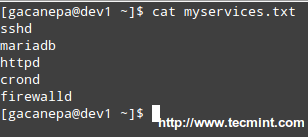

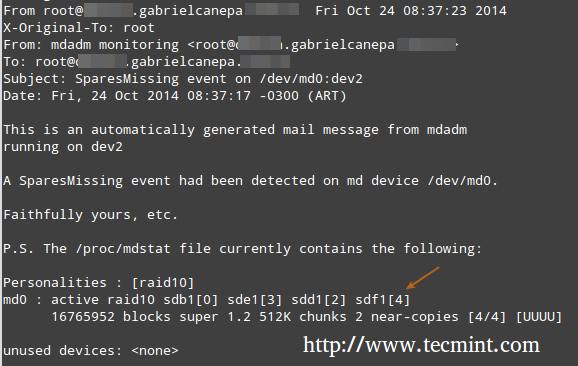

We will demonstrate the use of the if construct and the for loop with the following example.

|

||||

|

||||

**Determining if a service is running in a systemd-based distro**

|

||||

|

||||

Let’s create a file with a list of services that we want to monitor at a glance.

|

||||

|

||||

# cat myservices.txt

|

||||

|

||||

sshd

|

||||

mariadb

|

||||

httpd

|

||||

crond

|

||||

firewalld

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Script to Monitor Linux Services

|

||||

|

||||

Our shell script should look like.

|

||||

|

||||

#!/bin/bash

|

||||

|

||||

# This script iterates over a list of services and

|

||||

# is used to determine whether they are running or not.

|

||||

|

||||

for service in $(cat myservices.txt); do

|

||||

systemctl status $service | grep --quiet "running"

|

||||

if [ $? -eq 0 ]; then

|

||||

echo $service "is [ACTIVE]"

|

||||

else

|

||||

echo $service "is [INACTIVE or NOT INSTALLED]"

|

||||

fi

|

||||

done

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Linux Service Monitoring Script

|

||||

|

||||

**Let’s explain how the script works.**

|

||||

|

||||

1). The for loop reads the myservices.txt file one element of LIST at a time. That single element is denoted by the generic variable named service. The LIST is populated with the output of,

|

||||

|

||||

# cat myservices.txt

|

||||

|

||||

2). The above command is enclosed in parentheses and preceded by a dollar sign to indicate that it should be evaluated to populate the LIST that we will iterate over.

|

||||

|

||||

3). For each element of LIST (meaning every instance of the service variable), the following command will be executed.

|

||||

|

||||

# systemctl status $service | grep --quiet "running"

|

||||

|

||||

This time we need to precede our generic variable (which represents each element in LIST) with a dollar sign to indicate it’s a variable and thus its value in each iteration should be used. The output is then piped to grep.

|

||||

|

||||

The –quiet flag is used to prevent grep from displaying to the screen the lines where the word running appears. When that happens, the above command returns an exit status of 0 (represented by $? in the if construct), thus verifying that the service is running.

|

||||

|

||||

An exit status different than 0 (meaning the word running was not found in the output of systemctl status $service) indicates that the service is not running.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Services Monitoring Script

|

||||

|

||||

We could go one step further and check for the existence of myservices.txt before even attempting to enter the for loop.

|

||||

|

||||

#!/bin/bash

|

||||

|

||||

# This script iterates over a list of services and

|

||||

# is used to determine whether they are running or not.

|

||||

|

||||

if [ -f myservices.txt ]; then

|

||||

for service in $(cat myservices.txt); do

|

||||

systemctl status $service | grep --quiet "running"

|

||||

if [ $? -eq 0 ]; then

|

||||

echo $service "is [ACTIVE]"

|

||||

else

|

||||

echo $service "is [INACTIVE or NOT INSTALLED]"

|

||||

fi

|

||||

done

|

||||

else

|

||||

echo "myservices.txt is missing"

|

||||

fi

|

||||

|

||||

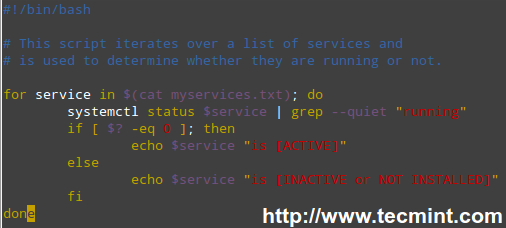

**Pinging a series of network or internet hosts for reply statistics**

|

||||

|

||||

You may want to maintain a list of hosts in a text file and use a script to determine every now and then whether they’re pingable or not (feel free to replace the contents of myhosts and try for yourself).

|

||||

|

||||

The read shell built-in command tells the while loop to read myhosts line by line and assigns the content of each line to variable host, which is then passed to the ping command.

|

||||

|

||||

#!/bin/bash

|

||||

|

||||

# This script is used to demonstrate the use of a while loop

|

||||

|

||||

while read host; do

|

||||

ping -c 2 $host

|

||||

done < myhosts

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Script to Ping Servers

|

||||

|

||||

Read Also:

|

||||

|

||||

- [Learn Shell Scripting: A Guide from Newbies to System Administrator][3]

|

||||

- [5 Shell Scripts to Learn Shell Programming][4]

|

||||

|

||||

### Filesystem Troubleshooting ###

|

||||

|

||||

Although Linux is a very stable operating system, if it crashes for some reason (for example, due to a power outage), one (or more) of your file systems will not be unmounted properly and thus will be automatically checked for errors when Linux is restarted.

|

||||

|

||||

In addition, each time the system boots during a normal boot, it always checks the integrity of the filesystems before mounting them. In both cases this is performed using a tool named fsck (“file system check”).

|

||||

|

||||

fsck will not only check the integrity of file systems, but also attempt to repair corrupt file systems if instructed to do so. Depending on the severity of damage, fsck may succeed or not; when it does, recovered portions of files are placed in the lost+found directory, located in the root of each file system.

|

||||

|

||||

Last but not least, we must note that inconsistencies may also happen if we try to remove an USB drive when the operating system is still writing to it, and may even result in hardware damage.

|

||||

|

||||

The basic syntax of fsck is as follows:

|

||||

|

||||

# fsck [options] filesystem

|

||||

|

||||

**Checking a filesystem for errors and attempting to repair automatically**

|

||||

|

||||

In order to check a filesystem with fsck, we must first unmount it.

|

||||

|

||||

# mount | grep sdg1

|

||||

# umount /mnt

|

||||

# fsck -y /dev/sdg1

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Check Filesystem Errors

|

||||

|

||||

Besides the -y flag, we can use the -a option to automatically repair the file systems without asking any questions, and force the check even when the filesystem looks clean.

|

||||

|

||||

# fsck -af /dev/sdg1

|

||||

|

||||

If we’re only interested in finding out what’s wrong (without trying to fix anything for the time being) we can run fsck with the -n option, which will output the filesystem issues to standard output.

|

||||

|

||||

# fsck -n /dev/sdg1

|

||||

|

||||

Depending on the error messages in the output of fsck, we will know whether we can try to solve the issue ourselves or escalate it to engineering teams to perform further checks on the hardware.

|

||||

|

||||

### Summary ###

|

||||

|

||||

We have arrived at the end of this 10-article series where have tried to cover the basic domain competencies required to pass the LFCS exam.

|

||||

|

||||

For obvious reasons, it is not possible to cover every single aspect of these topics in any single tutorial, and that’s why we hope that these articles have put you on the right track to try new stuff yourself and continue learning.

|

||||

|

||||

If you have any questions or comments, they are always welcome – so don’t hesitate to drop us a line via the form below!

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: http://www.tecmint.com/linux-basic-shell-scripting-and-linux-filesystem-troubleshooting/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Gabriel Cánepa][a]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创翻译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:http://www.tecmint.com/author/gacanepa/

|

||||

[1]:http://www.tecmint.com/sed-command-to-create-edit-and-manipulate-files-in-linux/

|

||||

[2]:http://www.tecmint.com/vi-editor-usage/

|

||||

[3]:http://www.tecmint.com/learning-shell-scripting-language-a-guide-from-newbies-to-system-administrator/

|

||||

[4]:http://www.tecmint.com/basic-shell-programming-part-ii/

|

||||

@ -0,0 +1,276 @@

|

||||

Part 6 - LFCS: Assembling Partitions as RAID Devices – Creating & Managing System Backups

|

||||

================================================================================

|

||||

Recently, the Linux Foundation launched the LFCS (Linux Foundation Certified Sysadmin) certification, a shiny chance for system administrators everywhere to demonstrate, through a performance-based exam, that they are capable of performing overall operational support on Linux systems: system support, first-level diagnosing and monitoring, plus issue escalation, when required, to other support teams.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Linux Foundation Certified Sysadmin – Part 6

|

||||

|

||||

The following video provides an introduction to The Linux Foundation Certification Program.

|

||||

|

||||

注:youtube 视频

|

||||

<iframe width="720" height="405" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen="allowfullscreen" src="//www.youtube.com/embed/Y29qZ71Kicg"></iframe>

|

||||

|

||||

This post is Part 6 of a 10-tutorial series, here in this part, we will explain How to Assemble Partitions as RAID Devices – Creating & Managing System Backups, that are required for the LFCS certification exam.

|

||||

|

||||

### Understanding RAID ###

|

||||

|

||||

The technology known as Redundant Array of Independent Disks (RAID) is a storage solution that combines multiple hard disks into a single logical unit to provide redundancy of data and/or improve performance in read / write operations to disk.

|

||||

|

||||

However, the actual fault-tolerance and disk I/O performance lean on how the hard disks are set up to form the disk array. Depending on the available devices and the fault tolerance / performance needs, different RAID levels are defined. You can refer to the RAID series here in Tecmint.com for a more detailed explanation on each RAID level.

|

||||

|

||||

- RAID Guide: [What is RAID, Concepts of RAID and RAID Levels Explained][1]

|

||||

|

||||

Our tool of choice for creating, assembling, managing, and monitoring our software RAIDs is called mdadm (short for multiple disks admin).

|

||||

|

||||

---------------- Debian and Derivatives ----------------

|

||||

# aptitude update && aptitude install mdadm

|

||||

|

||||

----------

|

||||

|

||||

---------------- Red Hat and CentOS based Systems ----------------

|

||||

# yum update && yum install mdadm

|

||||

|

||||

----------

|

||||

|

||||

---------------- On openSUSE ----------------

|

||||

# zypper refresh && zypper install mdadm #

|

||||

|

||||

#### Assembling Partitions as RAID Devices ####

|

||||

|

||||

The process of assembling existing partitions as RAID devices consists of the following steps.

|

||||

|

||||

**1. Create the array using mdadm**

|

||||

|

||||

If one of the partitions has been formatted previously, or has been a part of another RAID array previously, you will be prompted to confirm the creation of the new array. Assuming you have taken the necessary precautions to avoid losing important data that may have resided in them, you can safely type y and press Enter.

|

||||

|

||||

# mdadm --create --verbose /dev/md0 --level=stripe --raid-devices=2 /dev/sdb1 /dev/sdc1

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Creating RAID Array

|

||||

|

||||

**2. Check the array creation status**

|

||||

|

||||

After creating RAID array, you an check the status of the array using the following commands.

|

||||

|

||||

# cat /proc/mdstat

|

||||

or

|

||||

# mdadm --detail /dev/md0 [More detailed summary]

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Check RAID Array Status

|

||||

|

||||

**3. Format the RAID Device**

|

||||

|

||||

Format the device with a filesystem as per your needs / requirements, as explained in [Part 4][2] of this series.

|

||||

|

||||

**4. Monitor RAID Array Service**

|

||||

|

||||

Instruct the monitoring service to “keep an eye” on the array. Add the output of mdadm –detail –scan to /etc/mdadm/mdadm.conf (Debian and derivatives) or /etc/mdadm.conf (CentOS / openSUSE), like so.

|

||||

|

||||

# mdadm --detail --scan

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Monitor RAID Array

|

||||

|

||||

# mdadm --assemble --scan [Assemble the array]

|

||||

|

||||

To ensure the service starts on system boot, run the following commands as root.

|

||||

|

||||

**Debian and Derivatives**

|

||||

|

||||

Debian and derivatives, though it should start running on boot by default.

|

||||

|

||||

# update-rc.d mdadm defaults

|

||||

|

||||

Edit the /etc/default/mdadm file and add the following line.

|

||||

|

||||

AUTOSTART=true

|

||||

|

||||

**On CentOS and openSUSE (systemd-based)**

|

||||

|

||||

# systemctl start mdmonitor

|

||||

# systemctl enable mdmonitor

|

||||

|

||||

**On CentOS and openSUSE (SysVinit-based)**

|

||||

|

||||

# service mdmonitor start

|

||||

# chkconfig mdmonitor on

|

||||

|

||||

**5. Check RAID Disk Failure**

|

||||

|

||||

In RAID levels that support redundancy, replace failed drives when needed. When a device in the disk array becomes faulty, a rebuild automatically starts only if there was a spare device added when we first created the array.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Check RAID Faulty Disk

|

||||

|

||||

Otherwise, we need to manually attach an extra physical drive to our system and run.

|

||||

|

||||

# mdadm /dev/md0 --add /dev/sdX1

|

||||

|

||||

Where /dev/md0 is the array that experienced the issue and /dev/sdX1 is the new device.

|

||||

|

||||

**6. Disassemble a working array**

|

||||

|

||||

You may have to do this if you need to create a new array using the devices – (Optional Step).

|

||||

|

||||

# mdadm --stop /dev/md0 # Stop the array

|

||||

# mdadm --remove /dev/md0 # Remove the RAID device

|

||||

# mdadm --zero-superblock /dev/sdX1 # Overwrite the existing md superblock with zeroes

|

||||

|

||||

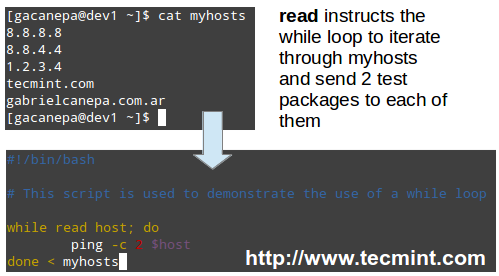

**7. Set up mail alerts**

|

||||

|

||||

You can configure a valid email address or system account to send alerts to (make sure you have this line in mdadm.conf). – (Optional Step)

|

||||

|

||||

MAILADDR root

|

||||

|

||||

In this case, all alerts that the RAID monitoring daemon collects will be sent to the local root account’s mail box. One of such alerts looks like the following.

|

||||

|

||||

**Note**: This event is related to the example in STEP 5, where a device was marked as faulty and the spare device was automatically built into the array by mdadm. Thus, we “ran out” of healthy spare devices and we got the alert.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

RAID Monitoring Alerts

|

||||

|

||||

#### Understanding RAID Levels ####

|

||||

|

||||

**RAID 0**

|

||||

|

||||

The total array size is n times the size of the smallest partition, where n is the number of independent disks in the array (you will need at least two drives). Run the following command to assemble a RAID 0 array using partitions /dev/sdb1 and /dev/sdc1.

|

||||

|

||||

# mdadm --create --verbose /dev/md0 --level=stripe --raid-devices=2 /dev/sdb1 /dev/sdc1

|

||||

|

||||

Common uses: Setups that support real-time applications where performance is more important than fault-tolerance.

|

||||

|

||||

**RAID 1 (aka Mirroring)**

|

||||

|

||||

The total array size equals the size of the smallest partition (you will need at least two drives). Run the following command to assemble a RAID 1 array using partitions /dev/sdb1 and /dev/sdc1.

|

||||

|

||||

# mdadm --create --verbose /dev/md0 --level=1 --raid-devices=2 /dev/sdb1 /dev/sdc1

|

||||

|

||||

Common uses: Installation of the operating system or important subdirectories, such as /home.

|

||||

|

||||

**RAID 5 (aka drives with Parity)**

|

||||

|

||||

The total array size will be (n – 1) times the size of the smallest partition. The “lost” space in (n-1) is used for parity (redundancy) calculation (you will need at least three drives).

|

||||

|

||||

Note that you can specify a spare device (/dev/sde1 in this case) to replace a faulty part when an issue occurs. Run the following command to assemble a RAID 5 array using partitions /dev/sdb1, /dev/sdc1, /dev/sdd1, and /dev/sde1 as spare.

|

||||

|

||||

# mdadm --create --verbose /dev/md0 --level=5 --raid-devices=3 /dev/sdb1 /dev/sdc1 /dev/sdd1 --spare-devices=1 /dev/sde1

|

||||

|

||||

Common uses: Web and file servers.

|

||||

|

||||

**RAID 6 (aka drives with double Parity**

|

||||

|

||||

The total array size will be (n*s)-2*s, where n is the number of independent disks in the array and s is the size of the smallest disk. Note that you can specify a spare device (/dev/sdf1 in this case) to replace a faulty part when an issue occurs.

|

||||

|

||||

Run the following command to assemble a RAID 6 array using partitions /dev/sdb1, /dev/sdc1, /dev/sdd1, /dev/sde1, and /dev/sdf1 as spare.

|

||||

|

||||

# mdadm --create --verbose /dev/md0 --level=6 --raid-devices=4 /dev/sdb1 /dev/sdc1 /dev/sdd1 /dev/sde --spare-devices=1 /dev/sdf1

|

||||

|

||||

Common uses: File and backup servers with large capacity and high availability requirements.

|

||||

|

||||

**RAID 1+0 (aka stripe of mirrors)**

|

||||

|

||||

The total array size is computed based on the formulas for RAID 0 and RAID 1, since RAID 1+0 is a combination of both. First, calculate the size of each mirror and then the size of the stripe.

|

||||

|

||||

Note that you can specify a spare device (/dev/sdf1 in this case) to replace a faulty part when an issue occurs. Run the following command to assemble a RAID 1+0 array using partitions /dev/sdb1, /dev/sdc1, /dev/sdd1, /dev/sde1, and /dev/sdf1 as spare.

|

||||

|

||||

# mdadm --create --verbose /dev/md0 --level=10 --raid-devices=4 /dev/sd[b-e]1 --spare-devices=1 /dev/sdf1

|

||||

|

||||

Common uses: Database and application servers that require fast I/O operations.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Creating and Managing System Backups ####

|

||||

|

||||

It never hurts to remember that RAID with all its bounties IS NOT A REPLACEMENT FOR BACKUPS! Write it 1000 times on the chalkboard if you need to, but make sure you keep that idea in mind at all times. Before we begin, we must note that there is no one-size-fits-all solution for system backups, but here are some things that you do need to take into account while planning a backup strategy.

|

||||

|

||||

- What do you use your system for? (Desktop or server? If the latter case applies, what are the most critical services – whose configuration would be a real pain to lose?)

|

||||

- How often do you need to take backups of your system?

|

||||

- What is the data (e.g. files / directories / database dumps) that you want to backup? You may also want to consider if you really need to backup huge files (such as audio or video files).

|

||||

- Where (meaning physical place and media) will those backups be stored?

|

||||

|

||||

**Backing Up Your Data**

|

||||

|

||||

Method 1: Backup entire drives with dd command. You can either back up an entire hard disk or a partition by creating an exact image at any point in time. Note that this works best when the device is offline, meaning it’s not mounted and there are no processes accessing it for I/O operations.

|

||||

|

||||

The downside of this backup approach is that the image will have the same size as the disk or partition, even when the actual data occupies a small percentage of it. For example, if you want to image a partition of 20 GB that is only 10% full, the image file will still be 20 GB in size. In other words, it’s not only the actual data that gets backed up, but the entire partition itself. You may consider using this method if you need exact backups of your devices.

|

||||

|

||||

**Creating an image file out of an existing device**

|

||||

|

||||

# dd if=/dev/sda of=/system_images/sda.img

|

||||

OR

|

||||

--------------------- Alternatively, you can compress the image file ---------------------

|

||||

# dd if=/dev/sda | gzip -c > /system_images/sda.img.gz

|

||||

|

||||

**Restoring the backup from the image file**

|

||||

|

||||

# dd if=/system_images/sda.img of=/dev/sda

|

||||

OR

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------- Depending on your choice while creating the image ---------------------

|

||||

gzip -dc /system_images/sda.img.gz | dd of=/dev/sda

|

||||

|

||||

Method 2: Backup certain files / directories with tar command – already covered in [Part 3][3] of this series. You may consider using this method if you need to keep copies of specific files and directories (configuration files, users’ home directories, and so on).

|

||||

|

||||

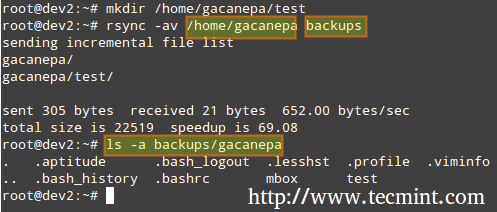

Method 3: Synchronize files with rsync command. Rsync is a versatile remote (and local) file-copying tool. If you need to backup and synchronize your files to/from network drives, rsync is a go.

|

||||

|

||||

Whether you’re synchronizing two local directories or local < — > remote directories mounted on the local filesystem, the basic syntax is the same.

|

||||

Synchronizing two local directories or local < — > remote directories mounted on the local filesystem

|

||||

|

||||

# rsync -av source_directory destination directory

|

||||

|

||||

Where, -a recurse into subdirectories (if they exist), preserve symbolic links, timestamps, permissions, and original owner / group and -v verbose.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

rsync Synchronizing Files

|

||||

|

||||

In addition, if you want to increase the security of the data transfer over the wire, you can use ssh over rsync.

|

||||

|

||||

**Synchronizing local → remote directories over ssh**

|

||||

|

||||

# rsync -avzhe ssh backups root@remote_host:/remote_directory/

|

||||

|

||||

This example will synchronize the backups directory on the local host with the contents of /root/remote_directory on the remote host.

|

||||

|

||||

Where the -h option shows file sizes in human-readable format, and the -e flag is used to indicate a ssh connection.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

rsync Synchronize Remote Files

|

||||

|

||||

Synchronizing remote → local directories over ssh.

|

||||

|

||||

In this case, switch the source and destination directories from the previous example.

|

||||

|

||||

# rsync -avzhe ssh root@remote_host:/remote_directory/ backups

|

||||

|

||||

Please note that these are only 3 examples (most frequent cases you’re likely to run into) of the use of rsync. For more examples and usages of rsync commands can be found at the following article.

|

||||

|

||||

- Read Also: [10 rsync Commands to Sync Files in Linux][4]

|

||||

|

||||

### Summary ###

|

||||

|

||||

As a sysadmin, you need to ensure that your systems perform as good as possible. If you’re well prepared, and if the integrity of your data is well supported by a storage technology such as RAID and regular system backups, you’ll be safe.

|

||||

|

||||

If you have questions, comments, or further ideas on how this article can be improved, feel free to speak out below. In addition, please consider sharing this series through your social network profiles.

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: http://www.tecmint.com/creating-and-managing-raid-backups-in-linux/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Gabriel Cánepa][a]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创翻译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:http://www.tecmint.com/author/gacanepa/

|

||||

[1]:http://www.tecmint.com/understanding-raid-setup-in-linux/

|

||||

[2]:http://www.tecmint.com/create-partitions-and-filesystems-in-linux/

|

||||

[3]:http://www.tecmint.com/compress-files-and-finding-files-in-linux/

|

||||

[4]:http://www.tecmint.com/rsync-local-remote-file-synchronization-commands/

|

||||

@ -0,0 +1,367 @@

|

||||

Part 7 - LFCS: Managing System Startup Process and Services (SysVinit, Systemd and Upstart)

|

||||

================================================================================

|

||||

A couple of months ago, the Linux Foundation announced the LFCS (Linux Foundation Certified Sysadmin) certification, an exciting new program whose aim is allowing individuals from all ends of the world to get certified in performing basic to intermediate system administration tasks on Linux systems. This includes supporting already running systems and services, along with first-hand problem-finding and analysis, plus the ability to decide when to raise issues to engineering teams.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Linux Foundation Certified Sysadmin – Part 7

|

||||

|

||||

The following video describes an brief introduction to The Linux Foundation Certification Program.

|

||||

|

||||

注:youtube 视频

|

||||

<iframe width="720" height="405" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen="allowfullscreen" src="//www.youtube.com/embed/Y29qZ71Kicg"></iframe>

|

||||

|

||||

This post is Part 7 of a 10-tutorial series, here in this part, we will explain how to Manage Linux System Startup Process and Services, that are required for the LFCS certification exam.

|

||||

|

||||

### Managing the Linux Startup Process ###

|

||||

|

||||

The boot process of a Linux system consists of several phases, each represented by a different component. The following diagram briefly summarizes the boot process and shows all the main components involved.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Linux Boot Process

|

||||

|

||||

When you press the Power button on your machine, the firmware that is stored in a EEPROM chip in the motherboard initializes the POST (Power-On Self Test) to check on the state of the system’s hardware resources. When the POST is finished, the firmware then searches and loads the 1st stage boot loader, located in the MBR or in the EFI partition of the first available disk, and gives control to it.

|

||||

|

||||

#### MBR Method ####

|

||||

|

||||

The MBR is located in the first sector of the disk marked as bootable in the BIOS settings and is 512 bytes in size.

|

||||

|

||||

- First 446 bytes: The bootloader contains both executable code and error message text.

|

||||

- Next 64 bytes: The Partition table contains a record for each of four partitions (primary or extended). Among other things, each record indicates the status (active / not active), size, and start / end sectors of each partition.

|

||||

- Last 2 bytes: The magic number serves as a validation check of the MBR.

|

||||

|

||||

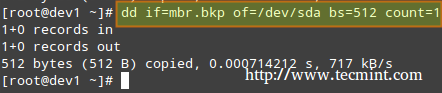

The following command performs a backup of the MBR (in this example, /dev/sda is the first hard disk). The resulting file, mbr.bkp can come in handy should the partition table become corrupt, for example, rendering the system unbootable.

|

||||

|

||||

Of course, in order to use it later if the need arises, we will need to save it and store it somewhere else (like a USB drive, for example). That file will help us restore the MBR and will get us going once again if and only if we do not change the hard drive layout in the meanwhile.

|

||||

|

||||

**Backup MBR**

|

||||

|

||||

# dd if=/dev/sda of=mbr.bkp bs=512 count=1

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Backup MBR in Linux

|

||||

|

||||

**Restoring MBR**

|

||||

|

||||

# dd if=mbr.bkp of=/dev/sda bs=512 count=1

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Restore MBR in Linux

|

||||

|

||||

#### EFI/UEFI Method ####

|

||||

|

||||

For systems using the EFI/UEFI method, the UEFI firmware reads its settings to determine which UEFI application is to be launched and from where (i.e., in which disk and partition the EFI partition is located).

|

||||

|

||||

Next, the 2nd stage boot loader (aka boot manager) is loaded and run. GRUB [GRand Unified Boot] is the most frequently used boot manager in Linux. One of two distinct versions can be found on most systems used today.

|

||||

|

||||

- GRUB legacy configuration file: /boot/grub/menu.lst (older distributions, not supported by EFI/UEFI firmwares).

|

||||

- GRUB2 configuration file: most likely, /etc/default/grub.

|

||||

|

||||

Although the objectives of the LFCS exam do not explicitly request knowledge about GRUB internals, if you’re brave and can afford to mess up your system (you may want to try it first on a virtual machine, just in case), you need to run.

|

||||

|

||||

# update-grub

|

||||

|

||||

As root after modifying GRUB’s configuration in order to apply the changes.

|

||||

|

||||

Basically, GRUB loads the default kernel and the initrd or initramfs image. In few words, initrd or initramfs help to perform the hardware detection, the kernel module loading and the device discovery necessary to get the real root filesystem mounted.

|

||||

|

||||

Once the real root filesystem is up, the kernel executes the system and service manager (init or systemd, whose process identification or PID is always 1) to begin the normal user-space boot process in order to present a user interface.

|

||||

|

||||

Both init and systemd are daemons (background processes) that manage other daemons, as the first service to start (during boot) and the last service to terminate (during shutdown).

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Systemd and Init

|

||||

|

||||

### Starting Services (SysVinit) ###

|

||||

|

||||

The concept of runlevels in Linux specifies different ways to use a system by controlling which services are running. In other words, a runlevel controls what tasks can be accomplished in the current execution state = runlevel (and which ones cannot).

|

||||

|

||||

Traditionally, this startup process was performed based on conventions that originated with System V UNIX, with the system passing executing collections of scripts that start and stop services as the machine entered a specific runlevel (which, in other words, is a different mode of running the system).

|

||||

|

||||

Within each runlevel, individual services can be set to run, or to be shut down if running. Latest versions of some major distributions are moving away from the System V standard in favour of a rather new service and system manager called systemd (which stands for system daemon), but usually support sysv commands for compatibility purposes. This means that you can run most of the well-known sysv init tools in a systemd-based distribution.

|

||||

|

||||

- Read Also: [Why ‘systemd’ replaces ‘init’ in Linux][1]

|

||||

|

||||

Besides starting the system process, init looks to the /etc/inittab file to decide what runlevel must be entered.

|

||||

|

||||

注:表格

|

||||

<table cellspacing="0" border="0">

|

||||

<colgroup width="85">

|

||||

</colgroup>

|

||||

<colgroup width="1514">

|

||||

</colgroup>

|

||||

<tbody>

|

||||

<tr>

|

||||

<td align="CENTER" height="18" style="border: 1px solid #000001;"><b>Runlevel</b></td>

|

||||

<td align="LEFT" style="border: 1px solid #000001;"><b> Description</b></td>

|

||||

</tr>

|

||||

<tr class="alt">

|

||||

<td align="CENTER" height="18" style="border: 1px solid #000001;">0</td>

|

||||

<td align="LEFT" style="border: 1px solid #000001;"> Halt the system. Runlevel 0 is a special transitional state used to shutdown the system quickly.</td>

|

||||

</tr>

|

||||

<tr>

|

||||

<td align="CENTER" height="20" style="border: 1px solid #000001;">1</td>

|

||||

<td align="LEFT" style="border: 1px solid #000001;"> Also aliased to s, or S, this runlevel is sometimes called maintenance mode. What services, if any, are started at this runlevel varies by distribution. It’s typically used for low-level system maintenance that may be impaired by normal system operation.</td>

|

||||

</tr>

|

||||

<tr class="alt">

|

||||

<td align="CENTER" height="18" style="border: 1px solid #000001;">2</td>

|

||||

<td align="LEFT" style="border: 1px solid #000001;"> Multiuser. On Debian systems and derivatives, this is the default runlevel, and includes -if available- a graphical login. On Red-Hat based systems, this is multiuser mode without networking.</td>

|

||||

</tr>

|

||||

<tr>

|

||||

<td align="CENTER" height="18" style="border: 1px solid #000001;">3</td>

|

||||

<td align="LEFT" style="border: 1px solid #000001;"> On Red-Hat based systems, this is the default multiuser mode, which runs everything except the graphical environment. This runlevel and levels 4 and 5 usually are not used on Debian-based systems.</td>

|

||||

</tr>

|

||||

<tr class="alt">

|

||||

<td align="CENTER" height="18" style="border: 1px solid #000001;">4</td>

|

||||

<td align="LEFT" style="border: 1px solid #000001;"> Typically unused by default and therefore available for customization.</td>

|

||||

</tr>

|

||||

<tr>

|

||||

<td align="CENTER" height="18" style="border: 1px solid #000001;">5</td>

|

||||

<td align="LEFT" style="border: 1px solid #000001;"> On Red-Hat based systems, full multiuser mode with GUI login. This runlevel is like level 3, but with a GUI login available.</td>

|

||||

</tr>

|

||||

<tr class="alt">

|

||||

<td align="CENTER" height="18" style="border: 1px solid #000001;">6</td>

|

||||

<td align="LEFT" style="border: 1px solid #000001;"> Reboot the system.</td>

|

||||

</tr>

|

||||

</tbody>

|

||||

</table>

|

||||

|

||||

To switch between runlevels, we can simply issue a runlevel change using the init command: init N (where N is one of the runlevels listed above). Please note that this is not the recommended way of taking a running system to a different runlevel because it gives no warning to existing logged-in users (thus causing them to lose work and processes to terminate abnormally).

|

||||

|

||||

Instead, the shutdown command should be used to restart the system (which first sends a warning message to all logged-in users and blocks any further logins; it then signals init to switch runlevels); however, the default runlevel (the one the system will boot to) must be edited in the /etc/inittab file first.

|

||||

|

||||

For that reason, follow these steps to properly switch between runlevels, As root, look for the following line in /etc/inittab.

|

||||

|

||||

id:2:initdefault:

|

||||

|

||||

and change the number 2 for the desired runlevel with your preferred text editor, such as vim (described in [How to use vi/vim editor in Linux – Part 2][2] of this series).

|

||||

|

||||

Next, run as root.

|

||||

|

||||

# shutdown -r now

|

||||

|

||||

That last command will restart the system, causing it to start in the specified runlevel during next boot, and will run the scripts located in the /etc/rc[runlevel].d directory in order to decide which services should be started and which ones should not. For example, for runlevel 2 in the following system.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Change Runlevels in Linux

|

||||

|

||||

#### Manage Services using chkconfig ####

|

||||

|

||||

To enable or disable system services on boot, we will use [chkconfig command][3] in CentOS / openSUSE and sysv-rc-conf in Debian and derivatives. This tool can also show us what is the preconfigured state of a service for a particular runlevel.

|

||||

|

||||

- Read Also: [How to Stop and Disable Unwanted Services in Linux][4]

|

||||

|

||||

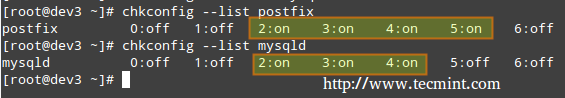

Listing the runlevel configuration for a service.

|

||||

|

||||

# chkconfig --list [service name]

|

||||

# chkconfig --list postfix

|

||||

# chkconfig --list mysqld

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Listing Runlevel Configuration

|

||||

|

||||

In the above image we can see that postfix is set to start when the system enters runlevels 2 through 5, whereas mysqld will be running by default for runlevels 2 through 4. Now suppose that this is not the expected behaviour.

|

||||

|

||||

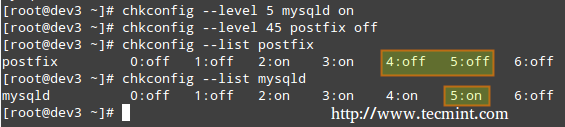

For example, we need to turn on mysqld for runlevel 5 as well, and turn off postfix for runlevels 4 and 5. Here’s what we would do in each case (run the following commands as root).

|

||||

|

||||

**Enabling a service for a particular runlevel**

|

||||

|

||||

# chkconfig --level [level(s)] service on

|

||||

# chkconfig --level 5 mysqld on

|

||||

|

||||

**Disabling a service for particular runlevels**

|

||||

|

||||

# chkconfig --level [level(s)] service off

|

||||

# chkconfig --level 45 postfix off

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Enable Disable Services

|

||||

|

||||

We will now perform similar tasks in a Debian-based system using sysv-rc-conf.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Manage Services using sysv-rc-conf ####

|

||||

|

||||

Configuring a service to start automatically on a specific runlevel and prevent it from starting on all others.

|

||||

|

||||

1. Let’s use the following command to see what are the runlevels where mdadm is configured to start.

|

||||

|

||||

# ls -l /etc/rc[0-6].d | grep -E 'rc[0-6]|mdadm'

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Check Runlevel of Service Running

|

||||

|

||||

2. We will use sysv-rc-conf to prevent mdadm from starting on all runlevels except 2. Just check or uncheck (with the space bar) as desired (you can move up, down, left, and right with the arrow keys).

|

||||

|

||||

# sysv-rc-conf

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

SysV Runlevel Config

|

||||

|

||||

Then press q to quit.

|

||||

|

||||

3. We will restart the system and run again the command from STEP 1.

|

||||

|

||||

# ls -l /etc/rc[0-6].d | grep -E 'rc[0-6]|mdadm'

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Verify Service Runlevel

|

||||

|

||||

In the above image we can see that mdadm is configured to start only on runlevel 2.

|

||||

|

||||

### What About systemd? ###

|

||||

|

||||

systemd is another service and system manager that is being adopted by several major Linux distributions. It aims to allow more processing to be done in parallel during system startup (unlike sysvinit, which always tends to be slower because it starts processes one at a time, checks whether one depends on another, and waits for daemons to launch so more services can start), and to serve as a dynamic resource management to a running system.

|

||||

|

||||

Thus, services are started when needed (to avoid consuming system resources) instead of being launched without a solid reason during boot.

|

||||

|

||||

Viewing the status of all the processes running on your system, both systemd native and SysV services, run the following command.

|

||||

|

||||

# systemctl

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Check All Running Processes

|

||||

|

||||

The LOAD column shows whether the unit definition (refer to the UNIT column, which shows the service or anything maintained by systemd) was properly loaded, while the ACTIVE and SUB columns show the current status of such unit.

|

||||

Displaying information about the current status of a service

|

||||

|

||||

When the ACTIVE column indicates that an unit’s status is other than active, we can check what happened using.

|

||||

|

||||

# systemctl status [unit]

|

||||

|

||||

For example, in the image above, media-samba.mount is in failed state. Let’s run.

|

||||

|

||||

# systemctl status media-samba.mount

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Check Service Status

|

||||

|

||||

We can see that media-samba.mount failed because the mount process on host dev1 was unable to find the network share at //192.168.0.10/gacanepa.

|

||||

|

||||

### Starting or Stopping Services ###

|

||||

|

||||

Once the network share //192.168.0.10/gacanepa becomes available, let’s try to start, then stop, and finally restart the unit media-samba.mount. After performing each action, let’s run systemctl status media-samba.mount to check on its status.

|

||||

|

||||

# systemctl start media-samba.mount

|

||||

# systemctl status media-samba.mount

|

||||

# systemctl stop media-samba.mount

|

||||

# systemctl restart media-samba.mount

|

||||

# systemctl status media-samba.mount

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Starting Stoping Services

|

||||

|

||||

**Enabling or disabling a service to start during boot**

|

||||

|

||||

Under systemd you can enable or disable a service when it boots.

|

||||

|

||||

# systemctl enable [service] # enable a service

|

||||

# systemctl disable [service] # prevent a service from starting at boot

|

||||

|

||||

The process of enabling or disabling a service to start automatically on boot consists in adding or removing symbolic links in the /etc/systemd/system/multi-user.target.wants directory.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Enabling Disabling Services

|

||||

|

||||

Alternatively, you can find out a service’s current status (enabled or disabled) with the command.

|

||||

|

||||

# systemctl is-enabled [service]

|

||||

|

||||

For example,

|

||||

|

||||

# systemctl is-enabled postfix.service

|

||||

|

||||

In addition, you can reboot or shutdown the system with.

|

||||

|

||||

# systemctl reboot

|

||||

# systemctl shutdown

|

||||

|

||||

### Upstart ###

|

||||

|

||||

Upstart is an event-based replacement for the /sbin/init daemon and was born out of the need for starting services only, when they are needed (also supervising them while they are running), and handling events as they occur, thus surpassing the classic, dependency-based sysvinit system.

|

||||

|

||||

It was originally developed for the Ubuntu distribution, but is used in Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.0. Though it was intended to be suitable for deployment in all Linux distributions as a replacement for sysvinit, in time it was overshadowed by systemd. On February 14, 2014, Mark Shuttleworth (founder of Canonical Ltd.) announced that future releases of Ubuntu would use systemd as the default init daemon.

|

||||

|

||||

Because the SysV startup script for system has been so common for so long, a large number of software packages include SysV startup scripts. To accommodate such packages, Upstart provides a compatibility mode: It runs SysV startup scripts in the usual locations (/etc/rc.d/rc?.d, /etc/init.d/rc?.d, /etc/rc?.d, or a similar location). Thus, if we install a package that doesn’t yet include an Upstart configuration script, it should still launch in the usual way.

|

||||

|

||||

Furthermore, if we have installed utilities such as [chkconfig][5], you should be able to use them to manage your SysV-based services just as we would on sysvinit based systems.

|

||||

|

||||

Upstart scripts also support starting or stopping services based on a wider variety of actions than do SysV startup scripts; for example, Upstart can launch a service whenever a particular hardware device is attached.

|

||||

|

||||

A system that uses Upstart and its native scripts exclusively replaces the /etc/inittab file and the runlevel-specific SysV startup script directories with .conf scripts in the /etc/init directory.

|

||||

|

||||

These *.conf scripts (also known as job definitions) generally consists of the following:

|

||||

|

||||

- Description of the process.

|

||||

- Runlevels where the process should run or events that should trigger it.

|

||||

- Runlevels where process should be stopped or events that should stop it.

|

||||

- Options.

|

||||

- Command to launch the process.

|

||||

|

||||

For example,

|

||||

|

||||

# My test service - Upstart script demo description "Here goes the description of 'My test service'" author "Dave Null <dave.null@example.com>"

|

||||

# Stanzas

|

||||

|

||||

#

|

||||

# Stanzas define when and how a process is started and stopped

|

||||

# See a list of stanzas here: http://upstart.ubuntu.com/wiki/Stanzas#respawn

|

||||

# When to start the service

|

||||

start on runlevel [2345]

|

||||

# When to stop the service

|

||||

stop on runlevel [016]

|

||||

# Automatically restart process in case of crash

|

||||

respawn

|

||||

# Specify working directory

|

||||

chdir /home/dave/myfiles

|

||||

# Specify the process/command (add arguments if needed) to run

|

||||

exec bash backup.sh arg1 arg2

|

||||

|

||||

To apply changes, you will need to tell upstart to reload its configuration.

|

||||

|

||||

# initctl reload-configuration

|

||||

|

||||

Then start your job by typing the following command.

|

||||

|

||||

$ sudo start yourjobname

|

||||

|

||||

Where yourjobname is the name of the job that was added earlier with the yourjobname.conf script.

|

||||

|

||||

A more complete and detailed reference guide for Upstart is available in the project’s web site under the menu “[Cookbook][6]”.

|

||||

|

||||

### Summary ###

|

||||

|

||||

A knowledge of the Linux boot process is necessary to help you with troubleshooting tasks as well as with adapting the computer’s performance and running services to your needs.

|

||||

|

||||

In this article we have analyzed what happens from the moment when you press the Power switch to turn on the machine until you get a fully operational user interface. I hope you have learned reading it as much as I did while putting it together. Feel free to leave your comments or questions below. We always look forward to hearing from our readers!

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: http://www.tecmint.com/linux-boot-process-and-manage-services/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Gabriel Cánepa][a]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创翻译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:http://www.tecmint.com/author/gacanepa/

|

||||

[1]:http://www.tecmint.com/systemd-replaces-init-in-linux/

|

||||

[2]:http://www.tecmint.com/vi-editor-usage/

|

||||

[3]:http://www.tecmint.com/chkconfig-command-examples/

|

||||

[4]:http://www.tecmint.com/remove-unwanted-services-from-linux/

|

||||

[5]:http://www.tecmint.com/chkconfig-command-examples/

|

||||

[6]:http://upstart.ubuntu.com/cookbook/

|

||||

@ -0,0 +1,330 @@

|

||||

Part 8 - LFCS: Managing Users & Groups, File Permissions & Attributes and Enabling sudo Access on Accounts

|

||||

================================================================================

|

||||

Last August, the Linux Foundation started the LFCS certification (Linux Foundation Certified Sysadmin), a brand new program whose purpose is to allow individuals everywhere and anywhere take an exam in order to get certified in basic to intermediate operational support for Linux systems, which includes supporting running systems and services, along with overall monitoring and analysis, plus intelligent decision-making to be able to decide when it’s necessary to escalate issues to higher level support teams.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Linux Foundation Certified Sysadmin – Part 8

|

||||

|

||||

Please have a quick look at the following video that describes an introduction to the Linux Foundation Certification Program.

|

||||

|

||||

注:youtube视频

|

||||

<iframe width="720" height="405" frameborder="0" allowfullscreen="allowfullscreen" src="//www.youtube.com/embed/Y29qZ71Kicg"></iframe>

|

||||

|

||||

This article is Part 8 of a 10-tutorial long series, here in this section, we will guide you on how to manage users and groups permissions in Linux system, that are required for the LFCS certification exam.

|

||||

|

||||

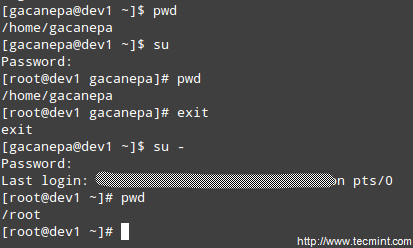

Since Linux is a multi-user operating system (in that it allows multiple users on different computers or terminals to access a single system), you will need to know how to perform effective user management: how to add, edit, suspend, or delete user accounts, along with granting them the necessary permissions to do their assigned tasks.

|

||||

|

||||

### Adding User Accounts ###

|

||||

|

||||

To add a new user account, you can run either of the following two commands as root.

|

||||

|

||||

# adduser [new_account]

|

||||

# useradd [new_account]

|

||||

|

||||

When a new user account is added to the system, the following operations are performed.

|

||||

|

||||

1. His/her home directory is created (/home/username by default).

|

||||

|

||||

2. The following hidden files are copied into the user’s home directory, and will be used to provide environment variables for his/her user session.

|

||||

|

||||

.bash_logout

|

||||

.bash_profile

|

||||

.bashrc

|

||||

|

||||

3. A mail spool is created for the user at /var/spool/mail/username.

|

||||

|

||||

4. A group is created and given the same name as the new user account.

|

||||

|

||||

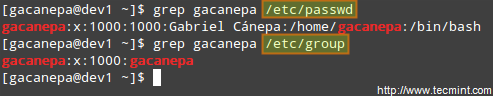

**Understanding /etc/passwd**

|

||||

|

||||

The full account information is stored in the /etc/passwd file. This file contains a record per system user account and has the following format (fields are delimited by a colon).

|

||||

|

||||

[username]:[x]:[UID]:[GID]:[Comment]:[Home directory]:[Default shell]

|

||||

|

||||

- Fields [username] and [Comment] are self explanatory.

|

||||

- The x in the second field indicates that the account is protected by a shadowed password (in /etc/shadow), which is needed to logon as [username].

|

||||

- The [UID] and [GID] fields are integers that represent the User IDentification and the primary Group IDentification to which [username] belongs, respectively.

|

||||

- The [Home directory] indicates the absolute path to [username]’s home directory, and

|

||||

- The [Default shell] is the shell that will be made available to this user when he or she logins the system.

|

||||

|

||||

**Understanding /etc/group**

|

||||

|

||||

Group information is stored in the /etc/group file. Each record has the following format.

|

||||

|

||||

[Group name]:[Group password]:[GID]:[Group members]

|

||||

|

||||

- [Group name] is the name of group.

|

||||

- An x in [Group password] indicates group passwords are not being used.

|

||||

- [GID]: same as in /etc/passwd.

|

||||

- [Group members]: a comma separated list of users who are members of [Group name].

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Add User Accounts

|

||||

|

||||

After adding an account, you can edit the following information (to name a few fields) using the usermod command, whose basic syntax of usermod is as follows.

|

||||

|

||||

# usermod [options] [username]

|

||||

|

||||

**Setting the expiry date for an account**

|

||||

|

||||

Use the –expiredate flag followed by a date in YYYY-MM-DD format.

|

||||

|

||||

# usermod --expiredate 2014-10-30 tecmint

|

||||

|

||||

**Adding the user to supplementary groups**

|

||||

|

||||

Use the combined -aG, or –append –groups options, followed by a comma separated list of groups.

|

||||

|

||||

# usermod --append --groups root,users tecmint

|

||||

|

||||

**Changing the default location of the user’s home directory**

|

||||

|

||||

Use the -d, or –home options, followed by the absolute path to the new home directory.

|

||||

|

||||

# usermod --home /tmp tecmint

|

||||

|

||||

**Changing the shell the user will use by default**

|

||||

|

||||

Use –shell, followed by the path to the new shell.

|

||||

|

||||

# usermod --shell /bin/sh tecmint

|

||||

|

||||

**Displaying the groups an user is a member of**

|

||||

|

||||

# groups tecmint

|

||||

# id tecmint

|

||||

|

||||

Now let’s execute all the above commands in one go.

|

||||

|

||||

# usermod --expiredate 2014-10-30 --append --groups root,users --home /tmp --shell /bin/sh tecmint

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

usermod Command Examples

|

||||

|

||||

Read Also:

|

||||

|

||||

- [15 useradd Command Examples in Linux][1]

|

||||

- [15 usermod Command Examples in Linux][2]

|

||||

|

||||

For existing accounts, we can also do the following.

|

||||

|

||||

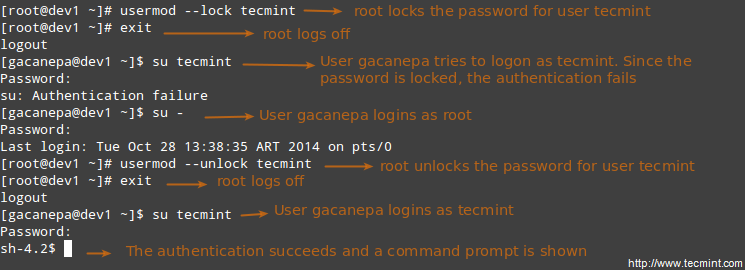

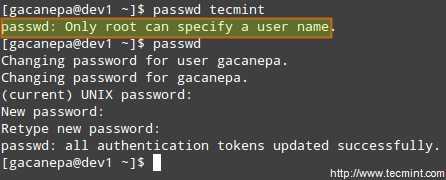

**Disabling account by locking password**

|

||||

|

||||

Use the -L (uppercase L) or the –lock option to lock a user’s password.

|

||||

|

||||

# usermod --lock tecmint

|

||||

|

||||

**Unlocking user password**

|

||||

|

||||

Use the –u or the –unlock option to unlock a user’s password that was previously blocked.

|

||||

|

||||

# usermod --unlock tecmint

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Lock User Accounts

|

||||

|

||||

**Creating a new group for read and write access to files that need to be accessed by several users**

|

||||

|

||||

Run the following series of commands to achieve the goal.

|

||||

|

||||

# groupadd common_group # Add a new group

|

||||

# chown :common_group common.txt # Change the group owner of common.txt to common_group

|

||||

# usermod -aG common_group user1 # Add user1 to common_group

|

||||

# usermod -aG common_group user2 # Add user2 to common_group

|

||||

# usermod -aG common_group user3 # Add user3 to common_group

|

||||

|

||||

**Deleting a group**

|

||||

|

||||

You can delete a group with the following command.

|

||||

|

||||

# groupdel [group_name]

|

||||

|

||||

If there are files owned by group_name, they will not be deleted, but the group owner will be set to the GID of the group that was deleted.

|

||||

|

||||

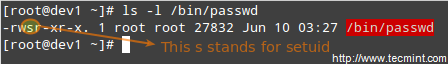

### Linux File Permissions ###

|

||||

|

||||

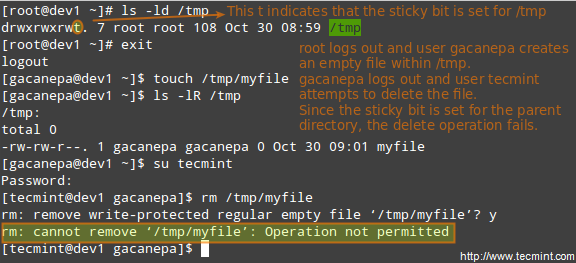

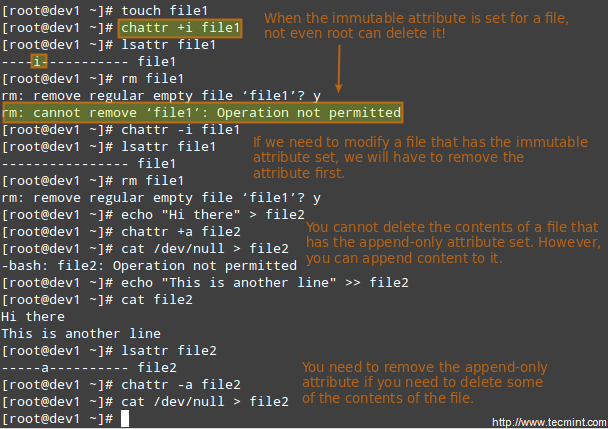

Besides the basic read, write, and execute permissions that we discussed in [Setting File Attributes – Part 3][3] of this series, there are other less used (but not less important) permission settings, sometimes referred to as “special permissions”.

|

||||

|

||||

Like the basic permissions discussed earlier, they are set using an octal file or through a letter (symbolic notation) that indicates the type of permission.

|

||||

Deleting user accounts

|

||||

|

||||

You can delete an account (along with its home directory, if it’s owned by the user, and all the files residing therein, and also the mail spool) using the userdel command with the –remove option.

|

||||

|

||||

# userdel --remove [username]

|

||||

|

||||

#### Group Management ####

|

||||

|

||||

Every time a new user account is added to the system, a group with the same name is created with the username as its only member. Other users can be added to the group later. One of the purposes of groups is to implement a simple access control to files and other system resources by setting the right permissions on those resources.

|

||||

|

||||

For example, suppose you have the following users.

|

||||