mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-03-15 01:50:08 +08:00

[Translated]/20180712 Slices from the ground up.md

This commit is contained in:

parent

adec1afd10

commit

d9f7c170a8

@ -1,263 +0,0 @@

|

||||

name1e5s is translating

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Slices from the ground up

|

||||

============================================================

|

||||

|

||||

This blog post was inspired by a conversation with a co-worker about using a slice as a stack. The conversation turned into a wider discussion on the way slices work in Go, so I thought it would be useful to write it up.

|

||||

|

||||

### Arrays

|

||||

|

||||

Every discussion of Go’s slice type starts by talking about something that isn’t a slice, namely, Go’s array type. Arrays in Go have two relevant properties:

|

||||

|

||||

1. They have a fixed size; `[5]int` is both an array of 5 `int`s and is distinct from `[3]int`.

|

||||

|

||||

2. They are value types. Consider this example:

|

||||

```

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

var a [5]int

|

||||

b := a

|

||||

b[2] = 7

|

||||

fmt.Println(a, b) // prints [0 0 0 0 0] [0 0 7 0 0]

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The statement `b := a` declares a new variable, `b`, of type `[5]int`, and _copies _ the contents of `a` to `b`. Updating `b` has no effect on the contents of `a` because `a` and `b` are independent values.[1][1]

|

||||

|

||||

### Slices

|

||||

|

||||

Go’s slice type differs from its array counterpart in two important ways:

|

||||

|

||||

1. Slices do not have a fixed length. A slice’s length is not declared as part of its type, rather it is held within the slice itself and is recoverable with the built-in function `len`.[2][2]

|

||||

|

||||

2. Assigning one slice variable to another _does not_ make a copy of the slices contents. This is because a slice does not directly hold its contents. Instead a slice holds a pointer to its _underlying_ array[3][3] which holds the contents of the slice.

|

||||

|

||||

As a result of the second property, two slices can share the same underlying array. Consider these examples:

|

||||

|

||||

1. Slicing a slice:

|

||||

```

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

var a = []int{1,2,3,4,5}

|

||||

b := a[2:]

|

||||

b[0] = 0

|

||||

fmt.Println(a, b) // prints [1 2 0 4 5] [0 4 5]

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

In this example `a` and `b` share the same underlying array–even though `b` starts at a different offset in that array, and has a different length. Changes to the underlying array via `b` are thus visible to `a`.

|

||||

|

||||

2. Passing a slice to a function:

|

||||

```

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func negate(s []int) {

|

||||

for i := range s {

|

||||

s[i] = -s[i]

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

var a = []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

|

||||

negate(a)

|

||||

fmt.Println(a) // prints [-1 -2 -3 -4 -5]

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

In this example `a` is passed to `negate`as the formal parameter `s.` `negate` iterates over the elements of `s`, negating their sign. Even though `negate` does not return a value, or have any way to access the declaration of `a` in `main`, the contents of `a` are modified when passed to `negate`.

|

||||

|

||||

Most programmers have an intuitive understanding of how a Go slice’s underlying array works because it matches how array-like concepts in other languages tend to work. For example, here’s the first example of this section rewritten in Python:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

Python 2.7.10 (default, Feb 7 2017, 00:08:15)

|

||||

[GCC 4.2.1 Compatible Apple LLVM 8.0.0 (clang-800.0.34)] on darwin

|

||||

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

|

||||

>>> a = [1,2,3,4,5]

|

||||

>>> b = a

|

||||

>>> b[2] = 0

|

||||

>>> a

|

||||

[1, 2, 0, 4, 5]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

And also in Ruby:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

irb(main):001:0> a = [1,2,3,4,5]

|

||||

=> [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

|

||||

irb(main):002:0> b = a

|

||||

=> [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

|

||||

irb(main):003:0> b[2] = 0

|

||||

=> 0

|

||||

irb(main):004:0> a

|

||||

=> [1, 2, 0, 4, 5]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The same applies to most languages that treat arrays as objects or reference types.[4][8]

|

||||

|

||||

### The slice header value

|

||||

|

||||

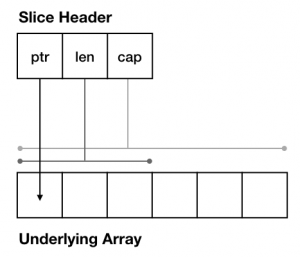

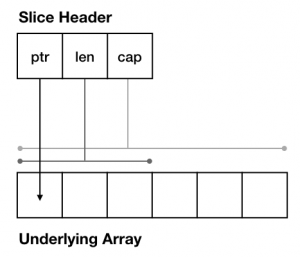

The magic that makes a slice behave both as a value and a pointer is to understand that a slice is actually a struct type. This is commonly referred to as a _slice header_ after its [counterpart in the reflect package][20]. The definition of a slice header looks something like this:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

package runtime

|

||||

|

||||

type slice struct {

|

||||

ptr unsafe.Pointer

|

||||

len int

|

||||

cap int

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This is important because [_unlike_ `map` and `chan`types][21] slices are value types and are _copied_ when assigned or passed as arguments to functions.

|

||||

|

||||

To illustrate this, programmers instinctively understand that `square`‘s formal parameter `v` is an independent copy of the `v` declared in `main`.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func square(v int) {

|

||||

v = v * v

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

v := 3

|

||||

square(v)

|

||||

fmt.Println(v) // prints 3, not 9

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

So the operation of `square` on its `v` has no effect on `main`‘s `v`. So too the formal parameter `s` of `double` is an independent copy of the slice `s` declared in `main`, _not_ a pointer to `main`‘s `s` value.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func double(s []int) {

|

||||

s = append(s, s...)

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

s := []int{1, 2, 3}

|

||||

double(s)

|

||||

fmt.Println(s, len(s)) // prints [1 2 3] 3

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The slightly unusual nature of a Go slice variable is it’s passed around as a value, not than a pointer. 90% of the time when you declare a struct in Go, you will pass around a pointer to values of that struct.[5][9] This is quite uncommon, the only other example of passing a struct around as a value I can think of off hand is `time.Time`.

|

||||

|

||||

It is this exceptional behaviour of slices as values, rather than pointers to values, that can confuses Go programmer’s understanding of how slices work. Just remember that any time you assign, subslice, or pass or return, a slice, you’re making a copy of the three fields in the slice header; the pointer to the underlying array, and the current length and capacity.

|

||||

|

||||

### Putting it all together

|

||||

|

||||

I’m going to conclude this post on the example of a slice as a stack that I opened this post with:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func f(s []string, level int) {

|

||||

if level > 5 {

|

||||

return

|

||||

}

|

||||

s = append(s, fmt.Sprint(level))

|

||||

f(s, level+1)

|

||||

fmt.Println("level:", level, "slice:", s)

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

f(nil, 0)

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Starting from `main` we pass a `nil` slice into `f` as `level` 0\. Inside `f` we append to `s` the current `level`before incrementing `level` and recursing. Once `level` exceeds 5, the calls to `f` return, printing their current level and the contents of their copy of `s`.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

level: 5 slice: [0 1 2 3 4 5]

|

||||

level: 4 slice: [0 1 2 3 4]

|

||||

level: 3 slice: [0 1 2 3]

|

||||

level: 2 slice: [0 1 2]

|

||||

level: 1 slice: [0 1]

|

||||

level: 0 slice: [0]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

You can see that at each level the value of `s` was unaffected by the operation of other callers of `f`, and that while four underlying arrays were created [6][10] higher levels of `f` in the call stack are unaffected by the copy and reallocation of new underlying arrays as a by-product of `append`.

|

||||

|

||||

### Further reading

|

||||

|

||||

If you want to find out more about how slices work in Go, I recommend these posts from the Go blog:

|

||||

|

||||

* [Go Slices: usage and internals][11] (blog.golang.org)

|

||||

|

||||

* [Arrays, slices (and strings): The mechanics of ‘append’][12] (blog.golang.org)

|

||||

|

||||

### Notes

|

||||

|

||||

1. This is not a unique property of arrays. In Go _every_ assignment is a copy.[][13]

|

||||

|

||||

2. You can also use `len` on array values, but the result is a forgone conclusion.[][14]

|

||||

|

||||

3. This is also known as the backing array or sometimes, less correctly, as the backing slice[][15]

|

||||

|

||||

4. In Go we tend to say value type and pointer type because of the confusion caused by C++’s _reference_ type, but in this case I think calling arrays as objects reference types is appropriate.[][16]

|

||||

|

||||

5. I’d argue if that struct has a [method defined on it and/or is used to satisfy an interface][17]then the percentage that you will pass around a pointer to your struct raises to near 100%.[][18]

|

||||

|

||||

6. Proof of this is left as an exercise to the reader.[][19]

|

||||

|

||||

### Related Posts:

|

||||

|

||||

1. [If a map isn’t a reference variable, what is it?][4]

|

||||

|

||||

2. [What is the zero value, and why is it useful ?][5]

|

||||

|

||||

3. [The empty struct][6]

|

||||

|

||||

4. [Should methods be declared on T or *T][7]

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Dave Cheney][a]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:https://dave.cheney.net/

|

||||

[1]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-bottom-1-3265

|

||||

[2]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-bottom-2-3265

|

||||

[3]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-bottom-3-3265

|

||||

[4]:https://dave.cheney.net/2017/04/30/if-a-map-isnt-a-reference-variable-what-is-it

|

||||

[5]:https://dave.cheney.net/2013/01/19/what-is-the-zero-value-and-why-is-it-useful

|

||||

[6]:https://dave.cheney.net/2014/03/25/the-empty-struct

|

||||

[7]:https://dave.cheney.net/2016/03/19/should-methods-be-declared-on-t-or-t

|

||||

[8]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-bottom-4-3265

|

||||

[9]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-bottom-5-3265

|

||||

[10]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-bottom-6-3265

|

||||

[11]:https://blog.golang.org/go-slices-usage-and-internals

|

||||

[12]:https://blog.golang.org/slices

|

||||

[13]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-1-3265

|

||||

[14]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-2-3265

|

||||

[15]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-3-3265

|

||||

[16]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-4-3265

|

||||

[17]:https://dave.cheney.net/2016/03/19/should-methods-be-declared-on-t-or-t

|

||||

[18]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-5-3265

|

||||

[19]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-6-3265

|

||||

[20]:https://golang.org/pkg/reflect/#SliceHeader

|

||||

[21]:https://dave.cheney.net/2017/04/30/if-a-map-isnt-a-reference-variable-what-is-it

|

||||

260

translated/tech/20180712 Slices from the ground up.md

Normal file

260

translated/tech/20180712 Slices from the ground up.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,260 @@

|

||||

Slices from the ground up

|

||||

============================================================

|

||||

|

||||

这篇文章最初的灵感来源于我与一个使用切片作栈的同事的一次聊天。那次聊天,话题最后拓展到了 Go 语言中的切片是如何工作的。我认为把这些知识记录下来会帮到别人。

|

||||

|

||||

### 数组

|

||||

|

||||

任何关于 Go 语言的切片的讨论都要从另一个数据结构,也就是 Go 语言的数组开始。Go 语言的数组有两个特性:

|

||||

|

||||

1. 数组的长度是固定的;`[5]int` 是由 5 个 `unt` 构成的数组,和`[3]int` 不同。

|

||||

|

||||

2. 数组是值类型。考虑如下示例:

|

||||

```

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

var a [5]int

|

||||

b := a

|

||||

b[2] = 7

|

||||

fmt.Println(a, b) // prints [0 0 0 0 0] [0 0 7 0 0]

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

语句 `b := a` 定义了一个新的变量 `b`,类型是 `[5]int`,然后把 `a` 中的内容_复制_到 `b` 中。改变 `b` 中的值对 `a` 中的内容没有影响,因为 `a` 和 `b` 是相互独立的值。 [1][1]

|

||||

|

||||

### 切片

|

||||

|

||||

Go 语言的切片和数组的主要有如下两个区别:

|

||||

|

||||

1. 切片没有一个固定的长度。切片的长度不是它类型定义的一部分,而是由切片内部自己维护的。我们可以使用内置的 `len` 函数知道他的长度。

|

||||

|

||||

2. 将一个切片赋值给另一个切片时 _不会_ 将切片进行复制操作。这是因为切片没有直接保存它的内部数据,而是保留了一个指向 _底层数组_ [3][3]的指针。数据都保留在底层数组里。

|

||||

|

||||

基于第二个特性,两个切片可以享有共同的底层数组。考虑如下示例:

|

||||

|

||||

1. 对切片取切片

|

||||

```

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

var a = []int{1,2,3,4,5}

|

||||

b := a[2:]

|

||||

b[0] = 0

|

||||

fmt.Println(a, b) // prints [1 2 0 4 5] [0 4 5]

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

在这个例子里,`a` 和 `b` 享有共同的底层数组 —— 尽管 `b` 的起始值在数组里的偏移不同,两者的长度也不同。通过 `b` 修改底层数组的值也会导致 `a` 里的值的改变。

|

||||

|

||||

2. 将切片传进函数

|

||||

```

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func negate(s []int) {

|

||||

for i := range s {

|

||||

s[i] = -s[i]

|

||||

}

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

var a = []int{1, 2, 3, 4, 5}

|

||||

negate(a)

|

||||

fmt.Println(a) // prints [-1 -2 -3 -4 -5]

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

在这个例子里,`a` 作为形参 `s` 的实参传进了 `negate` 函数,这个函数遍历 `s` 内的元素并改变其符号。尽管 `nagate` 没有返回值,且没有接触到 `main` 函数里的 `a`。但是当将之传进 `negate` 函数内时,`a` 里面的值却被改变了。

|

||||

|

||||

大多数程序员都能直观地了解 Go 语言切片的底层数组是如何工作的,因为它与其他语言中类似数组的工作方式类似。比如下面就是使用 Python 重写的这一小节的第一个示例:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

Python 2.7.10 (default, Feb 7 2017, 00:08:15)

|

||||

[GCC 4.2.1 Compatible Apple LLVM 8.0.0 (clang-800.0.34)] on darwin

|

||||

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

|

||||

>>> a = [1,2,3,4,5]

|

||||

>>> b = a

|

||||

>>> b[2] = 0

|

||||

>>> a

|

||||

[1, 2, 0, 4, 5]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

以及使用 Ruby 重写的版本:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

irb(main):001:0> a = [1,2,3,4,5]

|

||||

=> [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

|

||||

irb(main):002:0> b = a

|

||||

=> [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

|

||||

irb(main):003:0> b[2] = 0

|

||||

=> 0

|

||||

irb(main):004:0> a

|

||||

=> [1, 2, 0, 4, 5]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

在大多数将数组视为对象或者是引用类型的语言也是如此。[4][8]

|

||||

|

||||

### 切片头

|

||||

|

||||

让切片得以同时拥有值和指针的特性的魔法来源于切片实际上是一个结构体类型。这个结构体通常叫做 _切片头_,这里是 [反射包内的相关定义][20]。且片头的定义大致如下:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

package runtime

|

||||

|

||||

type slice struct {

|

||||

ptr unsafe.Pointer

|

||||

len int

|

||||

cap int

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

这个头很重要,因为和[ `map` 以及 `chan` 这两个类型不同][21],切片是值类型,当被赋值或者被作为函数的参数时候会被复制过去。

|

||||

|

||||

程序员们都能理解 `square` 的形参 `v` 和 `main` 中声明的 `v` 的是相互独立的,我们一次为例。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func square(v int) {

|

||||

v = v * v

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

v := 3

|

||||

square(v)

|

||||

fmt.Println(v) // prints 3, not 9

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

因此 `square` 对自己的形参 `v` 的操作没有影响到 `main` 中的 `v`。下面这个示例中的 `s` 也是 `main` 中声明的切片 `s` 的独立副本,_而不是_指向 `main` 的 `s` 的指针。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func double(s []int) {

|

||||

s = append(s, s...)

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

s := []int{1, 2, 3}

|

||||

double(s)

|

||||

fmt.Println(s, len(s)) // prints [1 2 3] 3

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Go 语言的切片是作为值传递的这一点很是不寻常。当你在 Go 语言内定义一个结构体时,90% 的时间里传递的都是这个结构体的指针。[5][9] 切片的传递方式真的很不寻常,我能想到的唯一与之相同的例子只有 `time.Time`。

|

||||

|

||||

切片作为值传递而不是作为指针传递这一点会让很多想要理解切片的工作原理的 Go 程序员感到困惑,这是可以理解的。你只需要记住,当你对切片进行赋值,取切片,传参或者作为返回值等操作时,你是在复制结构体内的三个位域:指针,长度,以及容量。

|

||||

|

||||

### 总结

|

||||

|

||||

我们来用我们引出这一话题的切片作为栈的例子来总结下本文的内容:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

package main

|

||||

|

||||

import "fmt"

|

||||

|

||||

func f(s []string, level int) {

|

||||

if level > 5 {

|

||||

return

|

||||

}

|

||||

s = append(s, fmt.Sprint(level))

|

||||

f(s, level+1)

|

||||

fmt.Println("level:", level, "slice:", s)

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

func main() {

|

||||

f(nil, 0)

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

在 `main` 函数的最开始我们把一个 `nil` 切片以及 `level` 0传给了函数 `f`。在函数 `f` 里我们把当前的 `level` 添加到切片的后面,之后增加 `level` 的值并进行递归。一旦 `level` 大于 5,函数返回,打印出当前的 `level` 以及他们复制到的 `s` 的内容。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

level: 5 slice: [0 1 2 3 4 5]

|

||||

level: 4 slice: [0 1 2 3 4]

|

||||

level: 3 slice: [0 1 2 3]

|

||||

level: 2 slice: [0 1 2]

|

||||

level: 1 slice: [0 1]

|

||||

level: 0 slice: [0]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

你可以注意到在每一个 `level` 内 `s` 的值没有被别的 `f` 的调用影响,尽管当计算更高阶的 `level` 时作为 `append` 的副产品,调用栈内的四个 `f` 函数创建了四个底层数组,但是没有影响到当前各自的切片。

|

||||

|

||||

### 了解更多

|

||||

|

||||

如果你想要了解更多 Go 语言内切片运行的原理,我建议看看 Go 博客里的这些文章:

|

||||

|

||||

* [Go Slices: usage and internals][11] (blog.golang.org)

|

||||

|

||||

* [Arrays, slices (and strings): The mechanics of ‘append’][12] (blog.golang.org)

|

||||

|

||||

### 注释

|

||||

|

||||

1. 这不是数组才有的特性,在 Go 语言里,_一切_ 赋值都是复制过去的,

|

||||

|

||||

2. 你可以在对数组使用 `len` 函数,但是得到的结果是多少人尽皆知。[][14]

|

||||

|

||||

3. 也叫做后台数组,以及更不严谨的说法是后台切片。[][15]

|

||||

|

||||

4. Go 语言里我们倾向于说值类型以及指针类型,因为 C++ 的引用会使使用引用类型这个词产生误会。但是在这里我说引用类型是没有问题的。[][16]

|

||||

|

||||

5. 如果你的结构体有[定义在其上的方法或者实现了什么接口][17],那么这个比率可以飙升到接近 100%。[][18]

|

||||

|

||||

6. 证明留做习题。

|

||||

|

||||

### 相关文章:

|

||||

|

||||

1. [If a map isn’t a reference variable, what is it?][4]

|

||||

|

||||

2. [What is the zero value, and why is it useful ?][5]

|

||||

|

||||

3. [The empty struct][6]

|

||||

|

||||

4. [Should methods be declared on T or *T][7]

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Dave Cheney][a]

|

||||

译者:[name1e5s](https://github.com/name1e5s)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:https://dave.cheney.net/

|

||||

[1]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-bottom-1-3265

|

||||

[2]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-bottom-2-3265

|

||||

[3]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-bottom-3-3265

|

||||

[4]:https://dave.cheney.net/2017/04/30/if-a-map-isnt-a-reference-variable-what-is-it

|

||||

[5]:https://dave.cheney.net/2013/01/19/what-is-the-zero-value-and-why-is-it-useful

|

||||

[6]:https://dave.cheney.net/2014/03/25/the-empty-struct

|

||||

[7]:https://dave.cheney.net/2016/03/19/should-methods-be-declared-on-t-or-t

|

||||

[8]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-bottom-4-3265

|

||||

[9]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-bottom-5-3265

|

||||

[10]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-bottom-6-3265

|

||||

[11]:https://blog.golang.org/go-slices-usage-and-internals

|

||||

[12]:https://blog.golang.org/slices

|

||||

[13]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-1-3265

|

||||

[14]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-2-3265

|

||||

[15]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-3-3265

|

||||

[16]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-4-3265

|

||||

[17]:https://dave.cheney.net/2016/03/19/should-methods-be-declared-on-t-or-t

|

||||

[18]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-5-3265

|

||||

[19]:https://dave.cheney.net/2018/07/12/slices-from-the-ground-up#easy-footnote-6-3265

|

||||

[20]:https://golang.org/pkg/reflect/#SliceHeader

|

||||

[21]:https://dave.cheney.net/2017/04/30/if-a-map-isnt-a-reference-variable-what-is-it

|

||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user