mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-03-06 01:20:12 +08:00

Merge remote-tracking branch 'LCTT/master'

This commit is contained in:

commit

cfdfe8f776

@ -1,196 +0,0 @@

|

||||

[#]: collector: (lujun9972)

|

||||

[#]: translator: (wxy)

|

||||

[#]: reviewer: ( )

|

||||

[#]: publisher: ( )

|

||||

[#]: url: ( )

|

||||

[#]: subject: (Virtual filesystems in Linux: Why we need them and how they work)

|

||||

[#]: via: (https://opensource.com/article/19/3/virtual-filesystems-linux)

|

||||

[#]: author: (Alison Chariken )

|

||||

|

||||

Virtual filesystems in Linux: Why we need them and how they work

|

||||

======

|

||||

Virtual filesystems are the magic abstraction that makes the "everything is a file" philosophy of Linux possible.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

What is a filesystem? According to early Linux contributor and author [Robert Love][1], "A filesystem is a hierarchical storage of data adhering to a specific structure." However, this description applies equally well to VFAT (Virtual File Allocation Table), Git, and [Cassandra][2] (a [NoSQL database][3]). So what distinguishes a filesystem?

|

||||

|

||||

### Filesystem basics

|

||||

|

||||

The Linux kernel requires that for an entity to be a filesystem, it must also implement the **open()** , **read()** , and **write()** methods on persistent objects that have names associated with them. From the point of view of [object-oriented programming][4], the kernel treats the generic filesystem as an abstract interface, and these big-three functions are "virtual," with no default definition. Accordingly, the kernel's default filesystem implementation is called a virtual filesystem (VFS).

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

![][5]

|

||||

If we can open(), read(), and write(), it is a file as this console session shows.

|

||||

|

||||

VFS underlies the famous observation that in Unix-like systems "everything is a file." Consider how weird it is that the tiny demo above featuring the character device /dev/console actually works. The image shows an interactive Bash session on a virtual teletype (tty). Sending a string into the virtual console device makes it appear on the virtual screen. VFS has other, even odder properties. For example, it's [possible to seek in them][6].

|

||||

|

||||

The familiar filesystems like ext4, NFS, and /proc all provide definitions of the big-three functions in a C-language data structure called [file_operations][7] . In addition, particular filesystems extend and override the VFS functions in the familiar object-oriented way. As Robert Love points out, the abstraction of VFS enables Linux users to blithely copy files to and from foreign operating systems or abstract entities like pipes without worrying about their internal data format. On behalf of userspace, via a system call, a process can copy from a file into the kernel's data structures with the read() method of one filesystem, then use the write() method of another kind of filesystem to output the data.

|

||||

|

||||

The function definitions that belong to the VFS base type itself are found in the [fs/*.c files][8] in kernel source, while the subdirectories of fs/ contain the specific filesystems. The kernel also contains filesystem-like entities such as cgroups, /dev, and tmpfs, which are needed early in the boot process and are therefore defined in the kernel's init/ subdirectory. Note that cgroups, /dev, and tmpfs do not call the file_operations big-three functions, but directly read from and write to memory instead.

|

||||

|

||||

The diagram below roughly illustrates how userspace accesses various types of filesystems commonly mounted on Linux systems. Not shown are constructs like pipes, dmesg, and POSIX clocks that also implement struct file_operations and whose accesses therefore pass through the VFS layer.

|

||||

|

||||

![How userspace accesses various types of filesystems][9]

|

||||

VFS are a "shim layer" between system calls and implementors of specific file_operations like ext4 and procfs. The file_operations functions can then communicate either with device-specific drivers or with memory accessors. tmpfs, devtmpfs and cgroups don't make use of file_operations but access memory directly.

|

||||

|

||||

VFS's existence promotes code reuse, as the basic methods associated with filesystems need not be re-implemented by every filesystem type. Code reuse is a widely accepted software engineering best practice! Alas, if the reused code [introduces serious bugs][10], then all the implementations that inherit the common methods suffer from them.

|

||||

|

||||

### /tmp: A simple tip

|

||||

|

||||

An easy way to find out what VFSes are present on a system is to type **mount | grep -v sd | grep -v :/** , which will list all mounted filesystems that are not resident on a disk and not NFS on most computers. One of the listed VFS mounts will assuredly be /tmp, right?

|

||||

|

||||

![Man with shocked expression][11]

|

||||

Everyone knows that keeping /tmp on a physical storage device is crazy! credit: <https://tinyurl.com/ybomxyfo>

|

||||

|

||||

Why is keeping /tmp on storage inadvisable? Because the files in /tmp are temporary(!), and storage devices are slower than memory, where tmpfs are created. Further, physical devices are more subject to wear from frequent writing than memory is. Last, files in /tmp may contain sensitive information, so having them disappear at every reboot is a feature.

|

||||

|

||||

Unfortunately, installation scripts for some Linux distros still create /tmp on a storage device by default. Do not despair should this be the case with your system. Follow simple instructions on the always excellent [Arch Wiki][12] to fix the problem, keeping in mind that memory allocated to tmpfs is not available for other purposes. In other words, a system with a gigantic tmpfs with large files in it can run out of memory and crash. Another tip: when editing the /etc/fstab file, be sure to end it with a newline, as your system will not boot otherwise. (Guess how I know.)

|

||||

|

||||

### /proc and /sys

|

||||

|

||||

Besides /tmp, the VFSes with which most Linux users are most familiar are /proc and /sys. (/dev relies on shared memory and has no file_operations). Why two flavors? Let's have a look in more detail.

|

||||

|

||||

The procfs offers a snapshot into the instantaneous state of the kernel and the processes that it controls for userspace. In /proc, the kernel publishes information about the facilities it provides, like interrupts, virtual memory, and the scheduler. In addition, /proc/sys is where the settings that are configurable via the [sysctl command][13] are accessible to userspace. Status and statistics on individual processes are reported in /proc/<PID> directories.

|

||||

|

||||

![Console][14]

|

||||

/proc/meminfo is an empty file that nonetheless contains valuable information.

|

||||

|

||||

The behavior of /proc files illustrates how unlike on-disk filesystems VFS can be. On the one hand, /proc/meminfo contains the information presented by the command **free**. On the other hand, it's also empty! How can this be? The situation is reminiscent of a famous article written by Cornell University physicist N. David Mermin in 1985 called "[Is the moon there when nobody looks?][15] Reality and the quantum theory." The truth is that the kernel gathers statistics about memory when a process requests them from /proc, and there actually is nothing in the files in /proc when no one is looking. As [Mermin said][16], "It is a fundamental quantum doctrine that a measurement does not, in general, reveal a preexisting value of the measured property." (The answer to the question about the moon is left as an exercise.)

|

||||

|

||||

![Full moon][17]

|

||||

The files in /proc are empty when no process accesses them. ([Source][18])

|

||||

|

||||

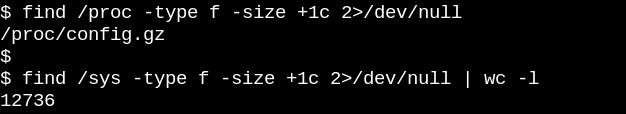

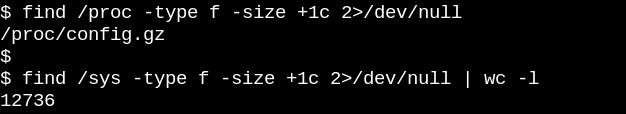

The apparent emptiness of procfs makes sense, as the information available there is dynamic. The situation with sysfs is different. Let's compare how many files of at least one byte in size there are in /proc versus /sys.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Procfs has precisely one, namely the exported kernel configuration, which is an exception since it needs to be generated only once per boot. On the other hand, /sys has lots of larger files, most of which comprise one page of memory. Typically, sysfs files contain exactly one number or string, in contrast to the tables of information produced by reading files like /proc/meminfo.

|

||||

|

||||

The purpose of sysfs is to expose the readable and writable properties of what the kernel calls "kobjects" to userspace. The only purpose of kobjects is reference-counting: when the last reference to a kobject is deleted, the system will reclaim the resources associated with it. Yet, /sys constitutes most of the kernel's famous "[stable ABI to userspace][19]" which [no one may ever, under any circumstances, "break."][20] That doesn't mean the files in sysfs are static, which would be contrary to reference-counting of volatile objects.

|

||||

|

||||

The kernel's stable ABI instead constrains what can appear in /sys, not what is actually present at any given instant. Listing the permissions on files in sysfs gives an idea of how the configurable, tunable parameters of devices, modules, filesystems, etc. can be set or read. Logic compels the conclusion that procfs is also part of the kernel's stable ABI, although the kernel's [documentation][19] doesn't state so explicitly.

|

||||

|

||||

![Console][21]

|

||||

Files in sysfs describe exactly one property each for an entity and may be readable, writable or both. The "0" in the file reveals that the SSD is not removable.

|

||||

|

||||

### Snooping on VFS with eBPF and bcc tools

|

||||

|

||||

The easiest way to learn how the kernel manages sysfs files is to watch it in action, and the simplest way to watch on ARM64 or x86_64 is to use eBPF. eBPF (extended Berkeley Packet Filter) consists of a [virtual machine running inside the kernel][22] that privileged users can query from the command line. Kernel source tells the reader what the kernel can do; running eBPF tools on a booted system shows instead what the kernel actually does.

|

||||

|

||||

Happily, getting started with eBPF is pretty easy via the [bcc][23] tools, which are available as [packages from major Linux distros][24] and have been [amply documented][25] by Brendan Gregg. The bcc tools are Python scripts with small embedded snippets of C, meaning anyone who is comfortable with either language can readily modify them. At this count, [there are 80 Python scripts in bcc/tools][26], making it highly likely that a system administrator or developer will find an existing one relevant to her/his needs.

|

||||

|

||||

To get a very crude idea about what work VFSes are performing on a running system, try the simple [vfscount][27] or [vfsstat][28], which show that dozens of calls to vfs_open() and its friends occur every second.

|

||||

|

||||

![Console - vfsstat.py][29]

|

||||

vfsstat.py is a Python script with an embedded C snippet that simply counts VFS function calls.

|

||||

|

||||

For a less trivial example, let's watch what happens in sysfs when a USB stick is inserted on a running system.

|

||||

|

||||

![Console when USB is inserted][30]

|

||||

Watch with eBPF what happens in /sys when a USB stick is inserted, with simple and complex examples.

|

||||

|

||||

In the first simple example above, the [trace.py][31] bcc tools script prints out a message whenever the sysfs_create_files() command runs. We see that sysfs_create_files() was started by a kworker thread in response to the USB stick insertion, but what file was created? The second example illustrates the full power of eBPF. Here, trace.py is printing the kernel backtrace (-K option) plus the name of the file created by sysfs_create_files(). The snippet inside the single quotes is some C source code, including an easily recognizable format string, that the provided Python script [induces a LLVM just-in-time compiler][32] to compile and execute inside an in-kernel virtual machine. The full sysfs_create_files() function signature must be reproduced in the second command so that the format string can refer to one of the parameters. Making mistakes in this C snippet results in recognizable C-compiler errors. For example, if the **-I** parameter is omitted, the result is "Failed to compile BPF text." Developers who are conversant with either C or Python will find the bcc tools easy to extend and modify.

|

||||

|

||||

When the USB stick is inserted, the kernel backtrace appears showing that PID 7711 is a kworker thread that created a file called "events" in sysfs. A corresponding invocation with sysfs_remove_files() shows that removal of the USB stick results in removal of the events file, in keeping with the idea of reference counting. Watching sysfs_create_link() with eBPF during USB stick insertion (not shown) reveals that no fewer than 48 symbolic links are created.

|

||||

|

||||

What is the purpose of the events file anyway? Using [cscope][33] to find the function [__device_add_disk()][34] reveals that it calls disk_add_events(), and either "media_change" or "eject_request" may be written to the events file. Here, the kernel's block layer is informing userspace about the appearance and disappearance of the "disk." Consider how quickly informative this method of investigating how USB stick insertion works is compared to trying to figure out the process solely from the source.

|

||||

|

||||

### Read-only root filesystems make embedded devices possible

|

||||

|

||||

Assuredly, no one shuts down a server or desktop system by pulling out the power plug. Why? Because mounted filesystems on the physical storage devices may have pending writes, and the data structures that record their state may become out of sync with what is written on the storage. When that happens, system owners will have to wait at next boot for the [fsck filesystem-recovery tool][35] to run and, in the worst case, will actually lose data.

|

||||

|

||||

Yet, aficionados will have heard that many IoT and embedded devices like routers, thermostats, and automobiles now run Linux. Many of these devices almost entirely lack a user interface, and there's no way to "unboot" them cleanly. Consider jump-starting a car with a dead battery where the power to the [Linux-running head unit][36] goes up and down repeatedly. How is it that the system boots without a long fsck when the engine finally starts running? The answer is that embedded devices rely on [a read-only root fileystem][37] (ro-rootfs for short).

|

||||

|

||||

![Photograph of a console][38]

|

||||

ro-rootfs are why embedded systems don't frequently need to fsck. Credit (with permission): <https://tinyurl.com/yxoauoub>

|

||||

|

||||

A ro-rootfs offers many advantages that are less obvious than incorruptibility. One is that malware cannot write to /usr or /lib if no Linux process can write there. Another is that a largely immutable filesystem is critical for field support of remote devices, as support personnel possess local systems that are nominally identical to those in the field. Perhaps the most important (but also most subtle) advantage is that ro-rootfs forces developers to decide during a project's design phase which system objects will be immutable. Dealing with ro-rootfs may often be inconvenient or even painful, as [const variables in programming languages][39] often are, but the benefits easily repay the extra overhead.

|

||||

|

||||

Creating a read-only rootfs does require some additional amount of effort for embedded developers, and that's where VFS comes in. Linux needs files in /var to be writable, and in addition, many popular applications that embedded systems run will try to create configuration dot-files in $HOME. One solution for configuration files in the home directory is typically to pregenerate them and build them into the rootfs. For /var, one approach is to mount it on a separate writable partition while / itself is mounted as read-only. Using bind or overlay mounts is another popular alternative.

|

||||

|

||||

### Bind and overlay mounts and their use by containers

|

||||

|

||||

Running **[man mount][40]** is the best place to learn about bind and overlay mounts, which give embedded developers and system administrators the power to create a filesystem in one path location and then provide it to applications at a second one. For embedded systems, the implication is that it's possible to store the files in /var on an unwritable flash device but overlay- or bind-mount a path in a tmpfs onto the /var path at boot so that applications can scrawl there to their heart's delight. At next power-on, the changes in /var will be gone. Overlay mounts provide a union between the tmpfs and the underlying filesystem and allow apparent modification to an existing file in a ro-rootfs, while bind mounts can make new empty tmpfs directories show up as writable at ro-rootfs paths. While overlayfs is a proper filesystem type, bind mounts are implemented by the [VFS namespace facility][41].

|

||||

|

||||

Based on the description of overlay and bind mounts, no one will be surprised that [Linux containers][42] make heavy use of them. Let's spy on what happens when we employ [systemd-nspawn][43] to start up a container by running bcc's mountsnoop tool:

|

||||

|

||||

![Console - system-nspawn invocation][44]

|

||||

The system-nspawn invocation fires up the container while mountsnoop.py runs.

|

||||

|

||||

And let's see what happened:

|

||||

|

||||

![Console - Running mountsnoop][45]

|

||||

Running mountsnoop during the container "boot" reveals that the container runtime relies heavily on bind mounts. (Only the beginning of the lengthy output is displayed)

|

||||

|

||||

Here, systemd-nspawn is providing selected files in the host's procfs and sysfs to the container at paths in its rootfs. Besides the MS_BIND flag that sets bind-mounting, some of the other flags that the "mount" system call invokes determine the relationship between changes in the host namespace and in the container. For example, the bind-mount can either propagate changes in /proc and /sys to the container, or hide them, depending on the invocation.

|

||||

|

||||

### Summary

|

||||

|

||||

Understanding Linux internals can seem an impossible task, as the kernel itself contains a gigantic amount of code, leaving aside Linux userspace applications and the system-call interface in C libraries like glibc. One way to make progress is to read the source code of one kernel subsystem with an emphasis on understanding the userspace-facing system calls and headers plus major kernel internal interfaces, exemplified here by the file_operations table. The file operations are what makes "everything is a file" actually work, so getting a handle on them is particularly satisfying. The kernel C source files in the top-level fs/ directory constitute its implementation of virtual filesystems, which are the shim layer that enables broad and relatively straightforward interoperability of popular filesystems and storage devices. Bind and overlay mounts via Linux namespaces are the VFS magic that makes containers and read-only root filesystems possible. In combination with a study of source code, the eBPF kernel facility and its bcc interface makes probing the kernel simpler than ever before.

|

||||

|

||||

Much thanks to [Akkana Peck][46] and [Michael Eager][47] for comments and corrections.

|

||||

|

||||

Alison Chaiken will present [Virtual filesystems: why we need them and how they work][48] at the 17th annual Southern California Linux Expo ([SCaLE 17x][49]) March 7-10 in Pasadena, Calif.

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://opensource.com/article/19/3/virtual-filesystems-linux

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Alison Chariken][a]

|

||||

选题:[lujun9972][b]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:

|

||||

[b]: https://github.com/lujun9972

|

||||

[1]: https://www.pearson.com/us/higher-education/program/Love-Linux-Kernel-Development-3rd-Edition/PGM202532.html

|

||||

[2]: http://cassandra.apache.org/

|

||||

[3]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NoSQL

|

||||

[4]: http://lwn.net/Articles/444910/

|

||||

[5]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_1-console.png (Console)

|

||||

[6]: https://lwn.net/Articles/22355/

|

||||

[7]: https://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux.git/tree/include/linux/fs.h

|

||||

[8]: https://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux.git/tree/fs

|

||||

[9]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_2-shim-layer.png (How userspace accesses various types of filesystems)

|

||||

[10]: https://lwn.net/Articles/774114/

|

||||

[11]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_3-crazy.jpg (Man with shocked expression)

|

||||

[12]: https://wiki.archlinux.org/index.php/Tmpfs

|

||||

[13]: http://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man8/sysctl.8.html

|

||||

[14]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_4-proc-meminfo.png (Console)

|

||||

[15]: http://www-f1.ijs.si/~ramsak/km1/mermin.moon.pdf

|

||||

[16]: https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/David_Mermin

|

||||

[17]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_5-moon.jpg (Full moon)

|

||||

[18]: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Moon#/media/File:Full_Moon_Luc_Viatour.jpg

|

||||

[19]: https://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux.git/tree/Documentation/ABI/stable

|

||||

[20]: https://lkml.org/lkml/2012/12/23/75

|

||||

[21]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_7-sysfs.png (Console)

|

||||

[22]: https://events.linuxfoundation.org/sites/events/files/slides/bpf_collabsummit_2015feb20.pdf

|

||||

[23]: https://github.com/iovisor/bcc

|

||||

[24]: https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/INSTALL.md

|

||||

[25]: http://brendangregg.com/ebpf.html

|

||||

[26]: https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/tree/master/tools

|

||||

[27]: https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/tools/vfscount_example.txt

|

||||

[28]: https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/tools/vfsstat.py

|

||||

[29]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_8-vfsstat.png (Console - vfsstat.py)

|

||||

[30]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_9-ebpf.png (Console when USB is inserted)

|

||||

[31]: https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/tools/trace_example.txt

|

||||

[32]: https://events.static.linuxfound.org/sites/events/files/slides/bpf_collabsummit_2015feb20.pdf

|

||||

[33]: http://northstar-www.dartmouth.edu/doc/solaris-forte/manuals/c/user_guide/cscope.html

|

||||

[34]: https://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux.git/tree/block/genhd.c#n665

|

||||

[35]: http://www.man7.org/linux/man-pages/man8/fsck.8.html

|

||||

[36]: https://wiki.automotivelinux.org/_media/eg-rhsa/agl_referencehardwarespec_v0.1.0_20171018.pdf

|

||||

[37]: https://elinux.org/images/1/1f/Read-only_rootfs.pdf

|

||||

[38]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_10-code.jpg (Photograph of a console)

|

||||

[39]: https://www.meetup.com/ACCU-Bay-Area/events/drpmvfytlbqb/

|

||||

[40]: http://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man8/mount.8.html

|

||||

[41]: https://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux.git/tree/Documentation/filesystems/sharedsubtree.txt

|

||||

[42]: https://coreos.com/os/docs/latest/kernel-modules.html

|

||||

[43]: https://www.freedesktop.org/software/systemd/man/systemd-nspawn.html

|

||||

[44]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_11-system-nspawn.png (Console - system-nspawn invocation)

|

||||

[45]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_12-mountsnoop.png (Console - Running mountsnoop)

|

||||

[46]: http://shallowsky.com/

|

||||

[47]: http://eagercon.com/

|

||||

[48]: https://www.socallinuxexpo.org/scale/17x/presentations/virtual-filesystems-why-we-need-them-and-how-they-work

|

||||

[49]: https://www.socallinuxexpo.org/

|

||||

@ -1,112 +0,0 @@

|

||||

[#]: collector: (lujun9972)

|

||||

[#]: translator: ( )

|

||||

[#]: reviewer: ( )

|

||||

[#]: publisher: ( )

|

||||

[#]: url: ( )

|

||||

[#]: subject: (How to Use 7Zip in Ubuntu and Other Linux [Quick Tip])

|

||||

[#]: via: (https://itsfoss.com/use-7zip-ubuntu-linux/)

|

||||

[#]: author: (Abhishek Prakash https://itsfoss.com/author/abhishek/)

|

||||

|

||||

How to Use 7Zip in Ubuntu and Other Linux [Quick Tip]

|

||||

======

|

||||

|

||||

_**Brief: Cannot extract .7z file in Linux? Learn how to install and use 7zip in Ubuntu and other Linux distributions.**_

|

||||

|

||||

[7Zip][1] (properly written as 7-Zip) is an archive format hugely popular among Windows users. A 7Zip archive file usually ends in .7z extension. It’s mostly an open source software barring a few part of the code that deals with unRAR.

|

||||

|

||||

The 7Zip support is not enabled by default in most Linux distributions. If you try to extract it, you may see this error:

|

||||

|

||||

_**Could not open this file type

|

||||

There is no command installed for 7-zip archive files. Do you want to search for a command to open this file?**_

|

||||

|

||||

![][2]

|

||||

|

||||

Don’t worry, you can easily install 7zip in Ubuntu or other Linux distributions.

|

||||

|

||||

The one problem you’ll notice if you try to use the [apt-get install command][3], you’ll see that there are no installation candidate that starts with 7zip. It’s because the 7Zip package in Linux is named [p7zip][4]., start with letter ‘p’ instead of the expected number ‘7’.

|

||||

|

||||

Let’s see how to install 7zip in Ubuntu and (possibly) other distributions.

|

||||

|

||||

### Install 7Zip in Ubuntu Linux

|

||||

|

||||

![][5]

|

||||

|

||||

First thing you need is to install the p7zip package. You’ll find three 7zip packages in Ubuntu: p7zip, p7zip-full and p7zip-rar.

|

||||

|

||||

The difference between p7zip and p7zip-full is that p7zip is a lighter version providing support only for .7z while the full version provides support for more 7z compression algorithms (for audio files etc).

|

||||

|

||||

The p7zip-rar package provides support for [RAR files][6] along with 7z.

|

||||

|

||||

Installing p7zip-full should be sufficient in most cases but you may also install p7zip-rar for additional support for the rar file.

|

||||

|

||||

p7zip packages are in the [universe repository in Ubuntu][7] so make sure that you have enabled it using this command:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

sudo add-apt-repository universe

|

||||

sudo apt update

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Use the following command to install 7zip support in Ubuntu and Debian based distributions.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

sudo apt install p7zip-full p7zip-rar

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

That’s good. Now you have 7zip archive support in your system.

|

||||

|

||||

[][8]

|

||||

|

||||

Suggested read Easily Share Files Between Linux, Windows And Mac Using NitroShare

|

||||

|

||||

### Extract 7Zip archive file in Linux

|

||||

|

||||

With 7Zip installed, you can either use the GUI or the command line to extract 7zip files in Linux.

|

||||

|

||||

In GUI, you can extract a .7z file as you extract any other compressed file. You right click on the file and proceed to extract it.

|

||||

|

||||

In terminal, you can extract a .7z archive file using this command:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

7z e file.7z

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

### Compress a file in 7zip archive format in Linux

|

||||

|

||||

You can compress a file in 7zip archive format graphically. Simply right click on the file/directory, and select **Compress**. You should see several types of archive format options. Choose .7z for 7zip.

|

||||

|

||||

![7zip Archive Ubuntu][9]

|

||||

|

||||

Alternatively, you can also use the command line. Here’s the command that you can use for this purpose:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

7z a OutputFile files_to_compress

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

By default, the archived file will have .7z extension. You can compress the file in zip format by specifying the extension (.zip) of the output file.

|

||||

|

||||

**Conclusion**

|

||||

|

||||

That’s it. See, how easy it is to use 7zip in Linux? I hope you liked this quick tip. If you have questions or suggestions, feel free to let me know the comment sections.

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://itsfoss.com/use-7zip-ubuntu-linux/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Abhishek Prakash][a]

|

||||

选题:[lujun9972][b]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]: https://itsfoss.com/author/abhishek/

|

||||

[b]: https://github.com/lujun9972

|

||||

[1]: https://www.7-zip.org/

|

||||

[2]: https://i0.wp.com/itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Install_7zip_ubuntu_1.png?ssl=1

|

||||

[3]: https://itsfoss.com/apt-get-linux-guide/

|

||||

[4]: https://sourceforge.net/projects/p7zip/

|

||||

[5]: https://i2.wp.com/itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/7zip-linux.png?resize=800%2C450&ssl=1

|

||||

[6]: https://itsfoss.com/use-rar-ubuntu-linux/

|

||||

[7]: https://itsfoss.com/ubuntu-repositories/

|

||||

[8]: https://itsfoss.com/easily-share-files-linux-windows-mac-nitroshare/

|

||||

[9]: https://i2.wp.com/itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/7zip-archive-ubuntu.png?resize=800%2C239&ssl=1

|

||||

@ -0,0 +1,211 @@

|

||||

[#]: collector: (lujun9972)

|

||||

[#]: translator: (wxy)

|

||||

[#]: reviewer: ( )

|

||||

[#]: publisher: ( )

|

||||

[#]: url: ( )

|

||||

[#]: subject: (Virtual filesystems in Linux: Why we need them and how they work)

|

||||

[#]: via: (https://opensource.com/article/19/3/virtual-filesystems-linux)

|

||||

[#]: author: (Alison Chariken )

|

||||

|

||||

Linux 中的虚拟文件系统

|

||||

======

|

||||

|

||||

> 虚拟文件系统是一种神奇的抽象,它使得 “一切皆文件” 哲学在 Linux 中成为了可能。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

什么是文件系统?根据早期的 Linux 贡献者和作家 [Robert Love][1] 所说,“文件系统是一个遵循特定结构的数据的分层存储。” 不过,这种描述也同样适用于 VFAT(虚拟文件分配表)、Git 和[Cassandra][2](一种 [NoSQL 数据库][3])。那么如何区别文件系统呢?

|

||||

|

||||

### 文件系统基础概念

|

||||

|

||||

Linux 内核要求文件系统必须是实体,它还必须在持久对象上实现 `open()`、`read()` 和 `write()` 方法,并且这些实体需要有与之关联的名字。从 [面向对象编程][4] 的角度来看,内核将通用文件系统视为一个抽象接口,这三大函数是“虚拟”的,没有默认定义。因此,内核的默认文件系统实现被称为虚拟文件系统(VFS)。

|

||||

|

||||

![][5]

|

||||

|

||||

如果我们能够 `open()`、`read()` 和 `write()`,它就是一个文件,如这个主控台会话所示。

|

||||

|

||||

VFS 是著名的类 Unix 系统中 “一切皆文件” 的基础。让我们看一下它有多奇怪,上面的小演示体现了字符设备 `/dev/console` 实际的工作。该图显示了一个在虚拟电传打字(tty)上的交互式 Bash 会话。将一个字符串发送到虚拟控制台设备会使其显示在虚拟屏幕上。而 VFS 甚至还有其它更奇怪的属性。例如,它[可以在其中寻址][6]。

|

||||

|

||||

熟悉的文件系统如 ext4、NFS 和 /proc 在名为 [file_operations] [7] 的 C 语言数据结构中都提供了三大函数的定义。此外,特定的文件系统会以熟悉的面向对象的方式扩展和覆盖了 VFS 功能。正如 Robert Love 指出的那样,VFS 的抽象使 Linux 用户可以轻松地将文件复制到(复制自)外部操作系统或抽象实体(如管道),而无需担心其内部数据格式。在用户空间,通过系统调用,进程可以使用一个文件系统的 `read()`方法从文件复制到内核的数据结构中,然后使用另一种文件系统的 `write()` 方法输出数据。

|

||||

|

||||

属于 VFS 基本类型的函数定义本身可以在内核源代码的 [fs/*.c 文件][8] 中找到,而 `fs/` 的子目录中包含了特定的文件系统。内核还包含了类似文件系统的实体,例如 cgroup、`/dev` 和 tmpfs,它们在引导过程的早期需要,因此定义在内核的 `init/` 子目录中。请注意,cgroup、`/dev` 和 tmpfs 不会调用 `file_operations` 的三大函数,而是直接读取和写入内存。

|

||||

|

||||

下图大致说明了用户空间如何访问通常挂载在 Linux 系统上的各种类型的文件系统。未显示的是像管道、dmesg 和 POSIX 时钟这样的结构,它们也实现了 `struct file_operations`,并且因此其访问要通过 VFS 层。

|

||||

|

||||

![How userspace accesses various types of filesystems][9]

|

||||

|

||||

VFS 是系统调用和特定 `file_operations` 的实现(如 ext4 和 procfs)之间的“垫片层”。然后,`file_operations` 函数可以与特定于设备的驱动程序或内存访问器进行通信。tmpfs、devtmpfs 和 cgroup 不使用 `file_operations` 而是直接访问内存。

|

||||

|

||||

VFS 的存在促进了代码重用,因为与文件系统相关的基本方法不需要由每种文件系统类型重新实现。代码重用是一种被广泛接受的软件工程最佳实践!唉,如果重用的代码[引入了严重的错误][10],那么继承常用方法的所有实现都会受到影响。

|

||||

|

||||

### /tmp:一个小提示

|

||||

|

||||

找出系统中存在的 VFS 的简单方法是键入 `mount | grep -v sd | grep -v :/`,在大多数计算机上,它将列出所有未驻留在磁盘上也不是 NFS 的已挂载文件系统。其中一个列出的 VFS 挂载肯定是 `/ tmp`,对吧?

|

||||

|

||||

![Man with shocked expression][11]

|

||||

|

||||

*每个人都知道把 /tmp 放在物理存储设备上简直是疯了!图片:<https://tinyurl.com/ybomxyfo>*

|

||||

|

||||

为什么把 `/tmp` 留在存储设备上是不可取的?因为 `/tmp` 中的文件是临时的(!),并且存储设备比内存慢,所以创建了 tmpfs 这种文件系统。此外,比起内存,物理设备频繁写入更容易磨损。最后,`/tmp` 中的文件可能包含敏感信息,因此在每次重新启动时让它们消失是一项功能。

|

||||

|

||||

不幸的是,默认情况下,某些 Linux 发行版的安装脚本仍会在存储设备上创建 /tmp。如果你的系统出现这种情况,请不要绝望。按照一直优秀的 [Arch Wiki][12] 上的简单说明来解决问题就行,记住分配给 tmpfs 的内存不能用于其他目的。换句话说,带有巨大 tmpfs 并且其中包含大文件的系统可能会耗尽内存并崩溃。另一个提示:编辑 `/etc/fstab` 文件时,请务必以换行符结束,否则系统将无法启动。(猜猜我怎么知道。)

|

||||

|

||||

### /proc 和 /sys

|

||||

|

||||

除了 `/tmp` 之外,大多数 Linux 用户最熟悉的 VFS 是 `/proc` 和 `/sys`。(`/dev` 依赖于共享内存,没有 `file_operations`)。为什么有两种?让我们来看看更多细节。

|

||||

|

||||

procfs 提供了内核的瞬时状态及其为用户空间控制的进程的快照。在 `/proc` 中,内核发布有关其提供的工具的信息,如中断、虚拟内存和调度程序。此外,`/proc/sys` 是存放可以通过 [sysctl 命令][13]配置的设置的地方,可供用户空间访问。单个进程的状态和统计信息在 `/proc/<PID>` 目录中报告。

|

||||

|

||||

![Console][14]

|

||||

|

||||

*/proc/meminfo 是一个空文件,但仍包含有价值的信息。*

|

||||

|

||||

`/proc` 文件的行为说明了 VFS 可以与磁盘上的文件系统不同。一方面,`/proc/meminfo` 包含命令 `free` 提供的信息。另一方面,它还是空的!怎么会这样?这种情况让人联想起康奈尔大学物理学家 N. David Mermin 在 1985 年写的一篇名为“[没有人看见月亮的情况吗?][15]现实和量子理论。”事实是当进程从 `/proc` 请求内存时内核再收集有关内存的统计信息,并且当没有人在查看时,`/proc` 中的文件实际上没有任何内容。正如 [Mermin 所说][16],“这是一个基本的量子学说,一般来说,测量不会揭示被测属性的预先存在的价值。”(关于月球的问题的答案留作练习。)

|

||||

|

||||

![Full moon][17]

|

||||

|

||||

*当没有进程访问它们时,/proc 中的文件为空。([来源][18])*

|

||||

|

||||

procfs 的空文件是有道理的,因为那里可用的信息是动态的。sysfs 的情况不同。让我们比较一下 `/proc` 与 `/sys` 中不为空的文件数量。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

procfs 只有一个,即导出的内核配置,这是一个例外,因为每次启动只需要生成一次。另一方面,`/sys` 有许多较大的文件,其中大多数包含一页内存。通常,sysfs 文件只包含一个数字或字符串,与通过读取 `/proc/meminfo` 等文件生成的信息表格形成鲜明对比。

|

||||

|

||||

sysfs 的目的是将内核称为“kobjects”的可读写属性公开给用户空间。kobjects 的唯一目的是引用计数:当删除对 kobject 的最后一个引用时,系统将回收与之关联的资源。然而,`/sys` 构成了内核著名的“[到用户空间的稳定 ABI][19]”,它的大部分内容[在任何情况下都没有人会“破坏”][20]。这并不意味着 sysfs 中的文件是静态,这与易失性对象的引用计数相反。

|

||||

|

||||

内核的稳定 ABI 反而限制了 `/sys` 中可能出现的内容,而不是任何给定时刻实际存在的内容。列出 sysfs 中文件的权限可以了解如何设置或读取设备、模块、文件系统等的可配置、可调参数。Logic 强调 procfs 也是内核稳定 ABI 的一部分的结论,尽管内核的[文档][19]没有明确说明。

|

||||

|

||||

![Console][21]

|

||||

|

||||

*sysfs 中的文件恰好描述了实体的每个属性,并且可以是可读的、可写的或两者兼而有之。文件中的“0”表示 SSD 不可移动的存储设备。*

|

||||

|

||||

### 用 eBPF 和 bcc 工具一窥 VFS 内部

|

||||

|

||||

了解内核如何管理 sysfs 文件的最简单方法是观察它的运行情况,在 ARM64 或 x86_64 上观看的最简单方法是使用 eBPF。eBPF(<ruby>扩展的伯克利数据包过滤器<rt>extended Berkeley Packet Filter</rt></ruby>)由[在内核中运行的虚拟机][22]组成,特权用户可以从命令行进行查询。内核源代码告诉读者内核可以做什么;在一个启动的系统上运行 eBPF 工具会显示内核实际上做了什么。

|

||||

|

||||

令人高兴的是,通过 [bcc][23] 工具入门使用 eBPF 非常容易,这些工具在[主要 Linux 发行版的软件包][24] 中都有,并且已经由 Brendan Gregg [充分地给出了文档说明][25]。bcc 工具是带有小段嵌入式 C 语言片段的 Python 脚本,这意味着任何对这两种语言熟悉的人都可以轻松修改它们。当前统计,[bcc/tools 中有 80 个 Python 脚本][26],使系统管理员或开发人员很有可能能够找到与她/他的需求相关的现有脚本。

|

||||

|

||||

要了解 VFS 在正在运行的系统上的工作情况,请尝试使用简单的 [vfscount][27] 或 [vfsstat][28],这表明每秒都会发生数十次对 `vfs_open()` 及其相关的调用

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

![Console - vfsstat.py][29]

|

||||

|

||||

*vfsstat.py 是一个带有嵌入式 C 片段的 Python 脚本,它只是计数 VFS 函数调用。*

|

||||

|

||||

作为一个不太重要的例子,让我们看一下在运行的系统上插入 USB 记忆棒时 sysfs 中会发生什么。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

![Console when USB is inserted][30]

|

||||

|

||||

*用 eBPF 观察插入 USB 记忆棒时 /sys 中会发生什么,简单的和复杂的例子。*

|

||||

|

||||

在上面的第一个简单示例中,只要 `sysfs_create_files()` 命令运行,[trace.py][31] bcc 工具脚本就会打印出一条消息。我们看到 `sysfs_create_files()` 由一个 kworker 线程启动,以响应 USB 棒插入事件,但是它创建了什么文件?第二个例子说明了 eBPF 的强大能力。这里,`trace.py` 正在打印内核回溯(`-K` 选项)以及 `sysfs_create_files()` 创建的文件的名称。单引号内的代码段是一些 C 源代码,包括一个易于识别的格式字符串,提供的 Python 脚本[引入 LLVM 即时编译器(JIT)][32] 在内核虚拟机内编译和执行它。必须在第二个命令中重现完整的 `sysfs_create_files()` 函数签名,以便格式字符串可以引用其中一个参数。在此 C 片段中出错会导致可识别的 C 编译器错误。例如,如果省略 `-I` 参数,则结果为“无法编译 BPF 文本”。熟悉 C 或 Python 的开发人员会发现 bcc 工具易于扩展和修改。

|

||||

|

||||

插入 USB 记忆棒后,内核回溯显示 PID 7711 是一个 kworker 线程,它在 sysfs 中创建了一个名为 `events` 的文件。使用 `sysfs_remove_files()` 进行相应的调用表明,删除 USB 记忆棒会导致删除该 `events` 文件,这与引用计数的想法保持一致。在 USB 棒插入期间(未显示)在 eBPF 中观察 `sysfs_create_link()` 表明创建了不少于 48 个符号链接。

|

||||

|

||||

无论如何,`events` 文件的目的是什么?使用 [cscope][33] 查找函数 [`__device_add_disk()`][34] 显示它调用 `disk_add_events()`,并且可以将 “media_change” 或 “eject_request” 写入到该文件。这里,内核的块层通知用户空间 “磁盘” 的出现和消失。考虑一下这种调查 USB 棒插入工作原理的方法与试图仅从源头中找出该过程的速度有多快。

|

||||

|

||||

### 只读根文件系统使得嵌入式设备成为可能

|

||||

|

||||

确实,没有人通过拔出电源插头来关闭服务器或桌面系统。为什么?因为物理存储设备上挂载的文件系统可能有挂起的(未完成的)写入,并且记录其状态的数据结构可能与写入存储器的内容不同步。当发生这种情况时,系统所有者将不得不在下次启动时等待 [fsck 文件系统恢复工具][35] 运行完成,在最坏的情况下,实际上会丢失数据。

|

||||

|

||||

然而,狂热爱好者会听说许多物联网和嵌入式设备,如路由器、恒温器和汽车现在都运行 Linux。许多这些设备几乎完全没有用户界面,并且没有办法干净地“解除启动”它们。想一想使用启动电池耗尽的汽车,其中[运行 Linux 的主机设备][36] 的电源会不断加电断电。当引擎最终开始运行时,系统如何在没有长时间 fsck 的情况下启动呢?答案是嵌入式设备依赖于[只读根文件系统][37](简称 ro-rootfs)。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

![Photograph of a console][38]

|

||||

|

||||

*ro-rootfs 是嵌入式系统不经常需要 fsck 的原因。 来源:<https://tinyurl.com/yxoauoub>*

|

||||

|

||||

ro-rootfs 提供了许多优点,虽然这些优点不如耐用性那么显然。一个是,如果没有 Linux 进程可以写入,那么恶意软件无法写入 `/usr` 或 `/lib`。另一个是,基本上不可变的文件系统对于远程设备的现场支持至关重要,因为支持人员拥有名义上与现场相同的本地系统。也许最重要(但也是最微妙)的优势是 ro-rootfs 迫使开发人员在项目的设计阶段就决定哪些系统对象是不可变的。处理 ro-rootfs 可能经常是不方便甚至是痛苦的,[编程语言中的常量变量][39]经常就是这样,但带来的好处很容易偿还额外的开销。

|

||||

|

||||

对于嵌入式开发人员,创建只读根文件系统确实需要做一些额外的工作,而这正是 VFS 的用武之地。Linux 需要 `/var` 中的文件可写,此外,嵌入式系统运行的许多流行应用程序将尝试在 `$HOME` 中创建配置点文件。放在家目录中的配置文件的一种解决方案通常是预生成它们并将它们构建到 rootfs 中。对于 `/var`,一种方法是将其挂载在单独的可写分区上,而 `/` 本身以只读方式挂载。使用绑定或叠加挂载是另一种流行的替代方案。

|

||||

|

||||

### 绑定和叠加挂载以及在容器中的使用

|

||||

|

||||

运行 [man mount][40] 是了解<ruby>绑定挂载<rt>bind mount</rt></ruby>和<ruby>叠加挂载<rt>overlay mount</rt></ruby>的最好办法,这使嵌入式开发人员和系统管理员能够在一个路径位置创建文件系统,然后在另外一个路径将其提供给应用程序。对于嵌入式系统,这代表着可以将文件存储在 `/var` 中的不可写闪存设备上,但是在启动时将 tmpfs 中的路径叠加挂载或绑定挂载到 `/var` 路径上,这样应用程序就可以在那里随意写它们的内容了。下次加电时,`/var` 中的变化将会消失。叠加挂载提供了 tmpfs 和底层文件系统之间的联合,允许对 ro-rootfs 中的现有文件进行直接修改,而绑定挂载可以使新的空 tmpfs 目录在 ro-rootfs 路径中显示为可写。虽然叠加文件系统是一种适当的文件系统类型,但绑定挂载由 [VFS 命名空间工具][41] 实现的。

|

||||

|

||||

根据叠加挂载和绑定挂载的描述,没有人会对 [Linux容器][42] 大量使用它们感到惊讶。让我们通过运行 bcc 的 `mountsnoop` 工具监视当使用 [systemd-nspawn][43] 启动容器时会发生什么:

|

||||

|

||||

![Console - system-nspawn invocation][44]

|

||||

|

||||

*在 mountsnoop.py 运行的同时,system-nspawn 调用启动容器。*

|

||||

|

||||

让我们看看发生了什么:

|

||||

|

||||

![Console - Running mountsnoop][45]

|

||||

|

||||

在容器 “启动” 期间运行 `mountsnoop` 可以看到容器运行时很大程度上依赖于绑定挂载。(仅显示冗长输出的开头)

|

||||

|

||||

这里,`systemd-nspawn` 将主机的 procfs 和 sysfs 中的选定文件其 rootfs 中的路径提供给容器按。除了设置绑定挂载时的 `MS_BIND` 标志之外,`mount` 系统调用的一些其他标志用于确定主机命名空间和容器中的更改之间的关系。例如,绑定挂载可以将 `/proc` 和 `/sys` 中的更改传播到容器,也可以隐藏它们,具体取决于调用。

|

||||

|

||||

### 总结

|

||||

|

||||

理解 Linux 内部结构似乎是一项不可能完成的任务,因为除了 Linux 用户空间应用程序和 glibc 这样的 C 库中的系统调用接口,内核本身也包含大量代码。取得进展的一种方法是阅读一个内核子系统的源代码,重点是理解面向用户空间的系统调用和头文件以及主要的内核内部接口,这里以 `file_operations` 表为例的。`file_operations` 使得“一切都是文件”可以实际工作,因此掌握它们收获特别大。顶级 `fs/` 目录中的内核 C 源文件构成了虚拟文件系统的实现,虚拟文件系统是支持流行的文件系统和存储设备的广泛且相对简单的互操作性的垫片层。通过 Linux 命名空间进行绑定挂载和覆盖挂载是 VFS 魔术,它使容器和只读根文件系统成为可能。结合对源代码的研究,eBPF 内核工具及其 bcc 接口使得探测内核比以往任何时候都更简单。

|

||||

|

||||

非常感谢 [Akkana Peck][46] 和 [Michael Eager][47] 的评论和指正。

|

||||

|

||||

Alison Chaiken 也于 3 月 7 日至 10 日在加利福尼亚州帕萨迪纳举行的第 17 届南加州 Linux 博览会([SCaLE 17x][49])上演讲了[本主题][48]。

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://opensource.com/article/19/3/virtual-filesystems-linux

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Alison Chariken][a]

|

||||

选题:[lujun9972][b]

|

||||

译者:[wxy](https://github.com/wxy)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]: https://opensource.com/users/chaiken

|

||||

[b]: https://github.com/lujun9972

|

||||

[1]: https://www.pearson.com/us/higher-education/program/Love-Linux-Kernel-Development-3rd-Edition/PGM202532.html

|

||||

[2]: http://cassandra.apache.org/

|

||||

[3]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/NoSQL

|

||||

[4]: http://lwn.net/Articles/444910/

|

||||

[5]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_1-console.png (Console)

|

||||

[6]: https://lwn.net/Articles/22355/

|

||||

[7]: https://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux.git/tree/include/linux/fs.h

|

||||

[8]: https://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux.git/tree/fs

|

||||

[9]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_2-shim-layer.png (How userspace accesses various types of filesystems)

|

||||

[10]: https://lwn.net/Articles/774114/

|

||||

[11]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_3-crazy.jpg (Man with shocked expression)

|

||||

[12]: https://wiki.archlinux.org/index.php/Tmpfs

|

||||

[13]: http://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man8/sysctl.8.html

|

||||

[14]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_4-proc-meminfo.png (Console)

|

||||

[15]: http://www-f1.ijs.si/~ramsak/km1/mermin.moon.pdf

|

||||

[16]: https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/David_Mermin

|

||||

[17]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_5-moon.jpg (Full moon)

|

||||

[18]: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Moon#/media/File:Full_Moon_Luc_Viatour.jpg

|

||||

[19]: https://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux.git/tree/Documentation/ABI/stable

|

||||

[20]: https://lkml.org/lkml/2012/12/23/75

|

||||

[21]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_7-sysfs.png (Console)

|

||||

[22]: https://events.linuxfoundation.org/sites/events/files/slides/bpf_collabsummit_2015feb20.pdf

|

||||

[23]: https://github.com/iovisor/bcc

|

||||

[24]: https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/INSTALL.md

|

||||

[25]: http://brendangregg.com/ebpf.html

|

||||

[26]: https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/tree/master/tools

|

||||

[27]: https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/tools/vfscount_example.txt

|

||||

[28]: https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/tools/vfsstat.py

|

||||

[29]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_8-vfsstat.png (Console - vfsstat.py)

|

||||

[30]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_9-ebpf.png (Console when USB is inserted)

|

||||

[31]: https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/tools/trace_example.txt

|

||||

[32]: https://events.static.linuxfound.org/sites/events/files/slides/bpf_collabsummit_2015feb20.pdf

|

||||

[33]: http://northstar-www.dartmouth.edu/doc/solaris-forte/manuals/c/user_guide/cscope.html

|

||||

[34]: https://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux.git/tree/block/genhd.c#n665

|

||||

[35]: http://www.man7.org/linux/man-pages/man8/fsck.8.html

|

||||

[36]: https://wiki.automotivelinux.org/_media/eg-rhsa/agl_referencehardwarespec_v0.1.0_20171018.pdf

|

||||

[37]: https://elinux.org/images/1/1f/Read-only_rootfs.pdf

|

||||

[38]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_10-code.jpg (Photograph of a console)

|

||||

[39]: https://www.meetup.com/ACCU-Bay-Area/events/drpmvfytlbqb/

|

||||

[40]: http://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man8/mount.8.html

|

||||

[41]: https://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux.git/tree/Documentation/filesystems/sharedsubtree.txt

|

||||

[42]: https://coreos.com/os/docs/latest/kernel-modules.html

|

||||

[43]: https://www.freedesktop.org/software/systemd/man/systemd-nspawn.html

|

||||

[44]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_11-system-nspawn.png (Console - system-nspawn invocation)

|

||||

[45]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/virtualfilesystems_12-mountsnoop.png (Console - Running mountsnoop)

|

||||

[46]: http://shallowsky.com/

|

||||

[47]: http://eagercon.com/

|

||||

[48]: https://www.socallinuxexpo.org/scale/17x/presentations/virtual-filesystems-why-we-need-them-and-how-they-work

|

||||

[49]: https://www.socallinuxexpo.org/

|

||||

@ -0,0 +1,112 @@

|

||||

[#]: collector: (lujun9972)

|

||||

[#]: translator: (warmfrog)

|

||||

[#]: reviewer: ( )

|

||||

[#]: publisher: ( )

|

||||

[#]: url: ( )

|

||||

[#]: subject: (How to Use 7Zip in Ubuntu and Other Linux [Quick Tip])

|

||||

[#]: via: (https://itsfoss.com/use-7zip-ubuntu-linux/)

|

||||

[#]: author: (Abhishek Prakash https://itsfoss.com/author/abhishek/)

|

||||

|

||||

如何在 Ubuntu 和其他 Linux 分发版上使用 7Zip [快速指南]

|

||||

====================================================

|

||||

|

||||

_**简介: 不能在 Linux 中提取 .7z 文件? 学习如何在 Ubuntu 和其他 Linux 分发版中安装和使用 7zip。**_

|

||||

|

||||

[7Zip][1](更适当的写法是 7-Zip)是一种在 Windows 用户中广泛流行的文档格式。一个 7Zip 文档文件通常以 .7z 扩展结尾。它大部分是开源的,除了包含一些少量解压 rar 文件的代码。

|

||||

|

||||

默认大多数 Linux 分发版不支持 7Zip。如果你试图提取它,你会看见这个错误:

|

||||

|

||||

_**不能打开这种文件类型

|

||||

没有已安装的适用 7-zip 文档文件的命令。你想搜索一个命令来打开这个文件吗**_

|

||||

|

||||

![][2]

|

||||

|

||||

不要担心,你可以轻松的在 Ubuntu 和其他 Linux 分发版中安装 7zip。

|

||||

|

||||

一个问题是你会注意到如果你试图用 [apt-get install 命令][3],你会发现没有以 7zip 开头的候选安装。因为在 Linux 中 7Zip 包的名字是 [p7zip][4]。以字母 ‘p’ 开头而不是预期的数字 ‘7’。

|

||||

|

||||

让我们看一下如何在 Ubuntu 和其他 Linux 分发版中安装 7zip。

|

||||

|

||||

### 在 Ubuntu Linux 中安装 7Zip

|

||||

|

||||

![][5]

|

||||

|

||||

你需要做的第一件事是安装 p7zip 包。你会在 Ubuntu 中发现 3 个包:p7zip,p7zip-full 和 pzip-rar。

|

||||

|

||||

pzip 和 p7zip-full 的不同是 pzip 是一个轻量级的版本,仅仅对 .7z 文件提供支持,而 full 版本提供了更多的 7z 压缩算法(例如音频文件)。

|

||||

|

||||

p7zip-rar 包在 7z 中提供了对 [RAR 文件][6] 的支持

|

||||

|

||||

安装 p7zip-full 在大多数情况下足够了,但是你可能想安装 p7zip-rar 来支持 rar 文件的解压。

|

||||

|

||||

p7zip 包在[ Ubuntu 的 universe 仓库][7] 因此保证你可以使用以下命令:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

sudo add-apt-repository universe

|

||||

sudo apt update

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

在 Ubuntu 和 基于 Debian 的分发版中使用以下命令。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

sudo apt install p7zip-full p7zip-rar

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

这很好。现在在你的系统之有了 7zip 文档的支持。

|

||||

|

||||

[][8]

|

||||

|

||||

建议使用 NitroShare 在 Linux,Windows 和 Mac 系统之间轻松共享文件。

|

||||

|

||||

### 在 Linux中提取 7Zip 文档文件

|

||||

|

||||

安装了 7Zip 后,在 Linux 中,你可以在图形用户界面或者 命令行中提取 7zip 文件。

|

||||

|

||||

在图形用户界面,你可以像提取其他压缩文件一样提取 .7z 文件。右击文件来提取它。

|

||||

|

||||

在终端中,你可以使用下列命令提取 .7z 文档文件:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

7z e file.7z

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

### 在 Linux 中压缩文件为 7zip 文档格式

|

||||

|

||||

你可以在图形界面压缩文件为 7zip 文档格式。简单的在文件或目录上右击,选择**压缩**。你应该看到几种类型的文件格式选项。选择 .7z。

|

||||

|

||||

![7zip Archive Ubuntu][9]

|

||||

|

||||

作为替换,你也可以在命令行中使用。这里是你可以用来压缩的命令:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

7z a 输出的文件名 要压缩的文件

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

默认,文档文件有 .7z 扩展。你可以压缩文件为 zip 格式通过在输出文件中指定0扩展(.zip)。

|

||||

|

||||

**总结**

|

||||

|

||||

就是这样。看,在 Linux 中使用 7zip 多简单?我希望你喜欢这个快速指南。如果你有问题或者建议,请随意在下方评论让我知道。

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://itsfoss.com/use-7zip-ubuntu-linux/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Abhishek Prakash][a]

|

||||

选题:[lujun9972][b]

|

||||

译者:[warmfrog](https://github.com/warmfrog)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]: https://itsfoss.com/author/abhishek/

|

||||

[b]: https://github.com/lujun9972

|

||||

[1]: https://www.7-zip.org/

|

||||

[2]: https://i0.wp.com/itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Install_7zip_ubuntu_1.png?ssl=1

|

||||

[3]: https://itsfoss.com/apt-get-linux-guide/

|

||||

[4]: https://sourceforge.net/projects/p7zip/

|

||||

[5]: https://i2.wp.com/itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/7zip-linux.png?resize=800%2C450&ssl=1

|

||||

[6]: https://itsfoss.com/use-rar-ubuntu-linux/

|

||||

[7]: https://itsfoss.com/ubuntu-repositories/

|

||||

[8]: https://itsfoss.com/easily-share-files-linux-windows-mac-nitroshare/

|

||||

[9]: https://i2.wp.com/itsfoss.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/7zip-archive-ubuntu.png?resize=800%2C239&ssl=1

|

||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user