mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-01-25 23:11:02 +08:00

erlinux translated

This commit is contained in:

parent

6ce09bc32f

commit

c0e9c0516c

@ -1,173 +0,0 @@

|

||||

erlinux translate...

|

||||

|

||||

Managing devices in Linux

|

||||

============================================================

|

||||

|

||||

>Explore how the /dev directory gives you direct access to your devices in Linux.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

>Image by :Opensource.com

|

||||

|

||||

There are many interesting features of the Linux directory structure. This month I cover some fascinating aspects of the /dev directory. Before you proceed any further with this article, I suggest that, if you have not already done so, you read my earlier articles, _[Everything is a file][1]_, and _[An introduction to Linux filesystems][2]_, both of which introduce some interesting Linux filesystem concepts. Go ahead—I will wait.

|

||||

|

||||

Great! Welcome back. Now we can proceed with a more detailed exploration of the /dev directory.

|

||||

|

||||

### Device files

|

||||

|

||||

Device files are also known as [device ][3][special files][4]. Device files are employed to provide the operating system and users an interface to the devices that they represent. All Linux device files are located in the /dev directory, which is an integral part of the root (/) filesystem because these device files must be available to the operating system during the boot process.

|

||||

|

||||

One of the most important things to remember about these device files is that they are most definitely not device drivers. They are more accurately described as portals to the device drivers. Data is passed from an application or the operating system to the device file which then passes it to the device driver which then sends it to the physical device. The reverse data path is also used, from the physical device through the device driver, the device file, and then to an application or another device.

|

||||

|

||||

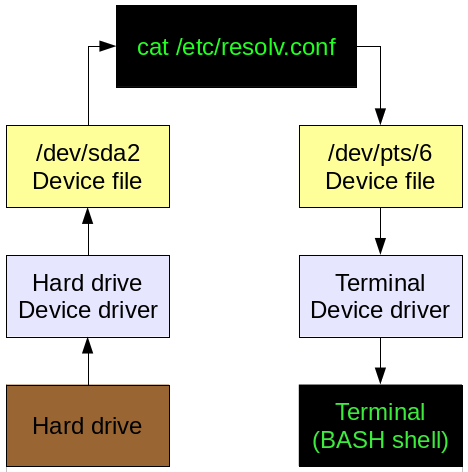

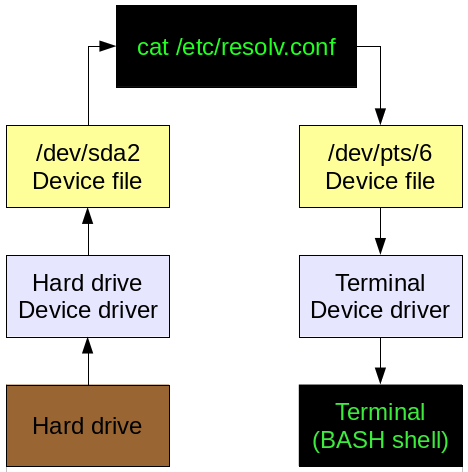

Let's look at the data flow of a typical command to visualize this.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Figure 1: Simple data flow for a typical command.</center>

|

||||

|

||||

In Figure 1, above, a simplified data flow is shown for a common command. Issuing the **cat /etc/resolv.conf** command from a GUI terminal emulator such as Konsole or xterm causes the resolv.conf file to be read from the disk with the disk device driver handling the device specific functions such as locating the file on the hard drive and reading it. The data is passed through the device file and then from the command to the device file and device driver for pseudo-terminal 6 where it is displayed in the terminal session.

|

||||

|

||||

Of course, the output of the **cat** command could have been redirected to a file in the following manner, **cat /etc/resolv.conf > /etc/resolv.bak** in order to create a backup of the file. In that case, the data flow on the left side of Figure 1 would remain the same while the data flow on the right would be through the /dev/sda2 device file, the hard drive device driver and then onto the hard drive itself.

|

||||

|

||||

These device files make it very easy to use standard streams (STD/IO) and redirection to access any and every device on a Linux or Unix computer. Simply directing a data stream to a device file sends the data to that device.

|

||||

|

||||

### Classification

|

||||

|

||||

Device files can be classified in at least two ways. The first and most commonly used classification is that of the data stream commonly associated with the device. For example, tty (teletype) and serial devices are considered to be character based because the data stream is transferred and handled one character or byte at a time. Block type devices such as hard drives transfer data in blocks, typically a multiple of 256 bytes.

|

||||

|

||||

If you have not already, go ahead and as a non-root user in a terminal session, change the present working directory (PWD) to /dev and display a long listing. This shows a list of device files with their file permissions and their major and minor identification numbers. For example, the following device files are just a few of the ones in the /dev/directory on my Fedora 24 workstation. They represent disk and tty type devices. Notice the leftmost character of each line in the output. The ones that have a "b" are block type devices and the ones that begin with "c" are character devices.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

brw-rw---- 1 root disk 8, 0 Nov 7 07:06 sda

|

||||

brw-rw---- 1 root disk 8, 1 Nov 7 07:06 sda1

|

||||

brw-rw---- 1 root disk 8, 16 Nov 7 07:06 sdb

|

||||

brw-rw---- 1 root disk 8, 17 Nov 7 07:06 sdb1

|

||||

brw-rw---- 1 root disk 8, 18 Nov 7 07:06 sdb2

|

||||

crw--w---- 1 root tty 4, 0 Nov 7 07:06 tty0

|

||||

crw--w---- 1 root tty 4, 1 Nov 7 07:07 tty1

|

||||

crw--w---- 1 root tty 4, 10 Nov 7 07:06 tty10

|

||||

crw--w---- 1 root tty 4, 11 Nov 7 07:06 tty11

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The more detailed and explicit way to identify device files is using the device major and minor numbers. The disk devices have a major number of 8 which designates them as SCSI block devices. Note that all PATA and SATA hard drives have been managed by the SCSI subsystem because the old ATA subsystem was many years ago deemed as not maintainable due to the poor quality of its code. As a result, hard drives that would previously have been designated as "hd[a-z]" are now referred to as "sd[a-z]".

|

||||

|

||||

You can probably infer the pattern of disk drive minor numbers in the small sample shown above. Minor numbers 0, 16, 32 and so on up through 240 are the whole disk numbers. So major/minor 8/16 represents the whole disk /dev/sdb and 8/17 is the device file for the first partition, /dev/sdb1\. Numbers 8/34 would be /dev/sdc2.

|

||||

|

||||

The tty device files in the list above are numbered a bit more simply from tty0 through tty63.

|

||||

|

||||

The [Linux Allocated Devices][5] file at Kernel.org is the official registry of device types and major and minor number allocations. It can help you understand the major/minor numbers for all currently defined devices.

|

||||

|

||||

### Fun with device files

|

||||

|

||||

Let's take a few minutes now and perform a couple fun experiments that will illustrate the power and flexibility of the Linux device files. Most Linux distributions have multiple virtual consoles, 1 through 7, that can be used to login to a local console session with a shell interface. These can be accessed using the key combinations Ctrl-Alt-F1 for console 1, Ctrl-Alt-F2 for console 2, and so on.

|

||||

|

||||

Press Ctrl-Alt-F2 to switch to console 2\. On some distributions, the login information includes the tty device associated with this console, but many do not. It should be tty2 because you are in console 2.

|

||||

|

||||

Log in as a non-root user. Then you can use the who am i command—yes, just like that, with spaces—to determine which tty device is connected to this console.

|

||||

|

||||

Before we actually perform this experiment, look at a listing of the tty2 and tty3 devices in /dev.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

ls -l /dev/tty[23]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

There will be a large number of tty devices defined but we do not care about most of them, just the tty2 and tty3 devices. As device files, there is nothing special about them; they are simply character type devices. We will use these devices for this experiment. The tty2 device is attached to virtual console 2 and the tty3 device is attached to virtual console 3.

|

||||

|

||||

Press Ctrl-Alt-F3 to switch to console 3\. Log in again as the same non-root user. Now enter the following command on console 3.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

echo "Hello world" > /dev/tty2

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Press Ctrl-Alt-F2 to return to console 2\. The string "Hello world" (without quotes) is displayed in console 2.

|

||||

|

||||

This experiment can also be performed with terminal emulators on the GUI desktop. Terminal sessions on the desktop use pseudo terminal devices in the /dev tree, such as /dev/pts/1\. Open two terminal sessions using Konsole or Xterm. Determine which pseudo-terminals they are connected to and use one to send a message to the other.

|

||||

|

||||

Now continue the experiment by using the cat command to display the /etc/fstab file on a different terminal.

|

||||

|

||||

Another interesting experiment is to print a file directly to the printer using the cat command. Assuming that your printer device is /dev/usb/lp0, and that your printer can print PDF files directly, the following command will print the PDF file test.pdf on your printer.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

cat test.pdf > /dev/usb/lp0

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The /dev directory contains some very interesting device files that are portals to hardware that one does not normally think of as a device like a hard drive or display. For one example, system memory—RAM—is not something that is normally considered as a "device," yet /dev/mem is the portal through which direct access to memory can be achieved. The following example had some interesting results.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

dd if=/dev/mem bs=2048 count=100

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The **dd** command above provides a bit more control than simply using the **cat**command to dump all of a system's memory. It provides the ability to specify how much data is read from /dev/mem and would also allow me to specify the point at which to start reading data from memory. Although some memory was read, the kernel responded with the following error that I found in /var/log/messages.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

Nov 14 14:37:31 david kernel: usercopy: kernel memory exposure attempt detected from ffff9f78c0010000 (dma-kmalloc-512) (2048 bytes)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

What this error means is that the kernel is doing its job by protecting memory that belongs to other processes which is exactly how it should work. So, although you can use /dev/mem to display data stored in RAM memory, access to most memory space is protected and will result in errors. Only that virtual memory which is assigned by the kernel memory manager to the BASH shell running the **dd** command should be accessible without causing an error. Sorry, but you cannot snoop in memory that does not belong to you unless you find a vulnerability to exploit.

|

||||

|

||||

There are some other very interesting device files in /dev. The device files null, zero, random and urandom are not associated with any physical devices.

|

||||

|

||||

For example, the null device /dev/null can be used as a target for the redirection of output from shell commands or programs so that they are not displayed on the terminal. I frequently use this in my BASH scripts to prevent users from being presented with output that might be confusing to them. The /dev/null device can be used to produce a string of null characters. Use the **dd** command as shown below to view some output from the /dev/null device file.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

# dd if=/dev/null bs=512 count=500 | od -c

|

||||

0+0 records in

|

||||

0+0 records out

|

||||

0 bytes copied, 1.5885e-05 s, 0.0 kB/s

|

||||

0000000

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Note that there is really no visible output because null characters are nothing. Note the byte count.

|

||||

|

||||

The /dev/random and /dev/urandom devices are also very interesting. As their names imply, they both produce random output—not just numbers but any and all byte combinations. The /dev/urandom device produces deterministic random output and is very fast. That means the output is determined by an algorithm and uses a seed string as a starting point. As a result it is possible, although very difficult, for a hacker to reproduce the output if the original seed is known. Use the command **cat /dev/urandom** to view typical output. You can use Ctrl-c to break out.

|

||||

|

||||

The /dev/random device file produces non-deterministic random output but it produces output more slowly. This output is not determined by an algorithm that is dependent upon the previous number, but is generated in response to keystrokes and mouse movements. This method makes it far more difficult to duplicate a specific series of random numbers. Use the **cat **command to view some of the output from the /dev/random device file. Try moving the mouse to see how it affects the output.

|

||||

|

||||

As its name implies, the /dev/zero device file produces an unending string of zeroes as output. Note that these are Octal zeroes and not the ASCII character zero (0). Use the **dd** command as shown below to view some output from the /dev/zero device file.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

# dd if=/dev/zero bs=512 count=500 | od -c

|

||||

0000000 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0

|

||||

*

|

||||

500+0 records in

|

||||

500+0 records out

|

||||

256000 bytes (256 kB, 250 KiB) copied, 0.00126996 s, 202 MB/s

|

||||

0764000

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Note that the byte count for this command is non-zero.

|

||||

|

||||

### Creating device files

|

||||

|

||||

In the past, the device files in /dev were all created at installation time, resulting in a directory full of almost every possible device file, even though most would never be used. In the unlikely event that a new device file was needed or one was accidentally deleted and needed to be re-created, the **mknod** program was available to manually create device files. All you had to know was the device major and minor numbers.

|

||||

|

||||

CentOS and RHEL 6 and 7, as well as all versions of Fedora going back to at least as far Fedora 15, use the newer method of creating the device files. All device files are created at boot time. This functionality is possible because the udev device manager detects addition and removal of devices as they occur. This allows for true dynamic plug-n-play functionality while the host is up and running. It also performs the same task at boot time by detecting all devices installed on the system very early in the boot process. [Linux.com][6] has a good [description of udev][7].

|

||||

|

||||

Going back to your listing of the files in /dev, notice the date and time on the files. All of them were created during the last boot. You can verify this using the **uptime**or **last** commands. In my device listing above, all of those files were created at 7:06 AM on November 7, which is the last time I booted the system.

|

||||

|

||||

Of course, the **mknod** command is still available, but the new **MAKEDEV** (yes, in all uppercase—which in my opinion is contrary to the Linux philosophy of using all lowercase command names) command provides an easier interface for creating device files, should the need arise. The MAKEDEV command is not installed by default in current versions of Fedora or CentOS 7; it is installed in CentOS 6\. You can use YUM or DNF to install the MAKEDEV package.

|

||||

|

||||

### Conclusion

|

||||

|

||||

Interestingly enough, it had been a long time since I needed to create a device file. However, just recently I had an interesting situation where one of the device files I typically use was not created and I did have to create it. I have not had any problem with that device since. So a situation caused by a missing device file can still happen and knowing how to deal with it can be important.

|

||||

|

||||

I have not covered many of the myriad different types of device files that you might encounter. That information is available in plenty of detail in the resources cited. I hope I have given you some basic understanding of how these files function and the tools to allow you to explore more on your own.

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://opensource.com/article/16/11/managing-devices-linux

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[David Both][a]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 组织编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:https://opensource.com/users/dboth

|

||||

[1]:https://opensource.com/life/15/9/everything-is-a-file

|

||||

[2]:https://opensource.com/life/16/10/introduction-linux-filesystems

|

||||

[3]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Device_file

|

||||

[4]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Device_file

|

||||

[5]:https://www.kernel.org/doc/Documentation/devices.txt

|

||||

[6]:https://www.linux.com/

|

||||

[7]:https://www.linux.com/news/udev-introduction-device-management-modern-linux-system

|

||||

172

translated/tech/20161128 Managing devices in Linux.md

Normal file

172

translated/tech/20161128 Managing devices in Linux.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,172 @@

|

||||

### 在 Linux 中管理设备

|

||||

|

||||

探索如何使您直接访问到 Linux 中的 /dev 目录设备。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

> Image by :Opensource.com

|

||||

|

||||

Linux 目录结构有很多有趣的功能,这个月我涉及(报导)了一些令人着迷的 /dev 目录。在继续这篇文章的任何操作之前,建议你看看我前面的文章。Linux 文件系统,一切皆为文件,这两个都介绍有趣的 Linux 文件系统概念。继续吗?我会等待。

|

||||

|

||||

太好了 !欢迎回来。现在我们可以继续进行更详尽地探讨 /dev 目录。

|

||||

|

||||

### 设备文件

|

||||

|

||||

设备文件也称为?驱动 ][3][special files][4]. 设备文件被操作系统用来代表提供给用户的设备接口。所有的 Linux 设备文件位于 /dev 目录,是根 (/) 文件系统的一个组成部分,因为这些设备文件要在操作系统启动过程中必须用到。

|

||||

|

||||

关于要记住这些设备文件最重要的事情之一是大多数没有明确的设备驱动。他们是更准确地描述为门户对设备驱动程序。数据从应用程序或操作系统传递到该设备文件,然后将它传递给设备驱动程序,再将它发给物理设备。反向数据通道也可以用,从物理设备通过设备驱动程序再到设备文件最后到达一个应用程序或其他设备。

|

||||

|

||||

让我们以一个可视化的典型命令看看这数据的流程。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

图1:典型命令的简单数据流。

|

||||

|

||||

在上面示出的图1中,显示一个简单命令的简化数据流程。**cat /etc/resolv.conf** 命令来自Konsole 或 xterm 终端仿真器解释 resolv.conf 文件从磁盘与磁盘设备驱动程序读取处理设备的具体功能。例如将文件定位在硬盘驱动器上并读取它。数据通过设备文件传递,然后命令终端会话中的显示位置从设备文件到设备驱动程序为 6 的伪终端。

|

||||

|

||||

当然,输出命令 **cat** 可以以下面的方式被重定向到一个文件 **cat /etc/resolv.conf > /etc/resolv.bak** 创建文件的备份。

|

||||

|

||||

在这种情况下,图 1 左侧的数据流量将保持不变而右边的数据流量将通过 /dev/sda2 设备文件,硬盘设备驱动程序,然后到硬驱动器本身。

|

||||

|

||||

这些设备文件使它使用标准流 (STD/IO) 和重定向访问Linux 或 Unix 计算机上的任何一个设备非常容易。只需将数据流定向到设备文件即可将数据发送到该设备。

|

||||

|

||||

### 设备文件类别

|

||||

|

||||

设备文件至少可以被分为两种方式。最常用的第一种分类通常是与设备相关联数据的数据流。比如,虚拟终端 (电报交换机) 并且串行设备被认为是基于字符的,因为数据流一次被传送和处理一个字符或字节。 块类型设备(如硬盘驱动器)以块为单位传输数据,通常为256个字节的倍数。

|

||||

|

||||

如果你还没有准备好继续前进,在终端会话一个非root用户,改变目前的工作目录(PWD)到 /dev 和显示的长目录列表。 这将显示设备文件列表及其文件权限及其主要和次要标识号。 例如,下面的设备文件只是 Fedora 24 工作站上 /dev 目录中的几个文件。 它们表示磁盘和tty设备类型。 注意输出中每行的最左边的字符。 具有“b”的是块类型设备,以“c”开头的是字符设备。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

brw-rw---- 1 root disk 8, 0 Nov 7 07:06 sda

|

||||

brw-rw---- 1 root disk 8, 1 Nov 7 07:06 sda1

|

||||

brw-rw---- 1 root disk 8, 16 Nov 7 07:06 sdb

|

||||

brw-rw---- 1 root disk 8, 17 Nov 7 07:06 sdb1

|

||||

brw-rw---- 1 root disk 8, 18 Nov 7 07:06 sdb2

|

||||

crw--w---- 1 root tty 4, 0 Nov 7 07:06 tty0

|

||||

crw--w---- 1 root tty 4, 1 Nov 7 07:07 tty1

|

||||

crw--w---- 1 root tty 4, 10 Nov 7 07:06 tty10

|

||||

crw--w---- 1 root tty 4, 11 Nov 7 07:06 tty11

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

识别设备文件更详细和更明确的方法是使用设备主要以及次要码。 磁盘设备具有主数字8,其将它们指定为SCSI块设备。 请注意,所有PATA和SATA硬盘驱动器都由SCSI子系统管理,因为旧的ATA子系统多年前被认为是不可维护的,因为它的代码质量差。 造成的结果是,以前被称为“hd [a-z]”的硬盘驱动器现在被称为“sd [a-z]”。

|

||||

|

||||

你大概可以推断出磁盘驱动器次要设备号如上示例所示的模式。小数字 0、 16、 32 等等,通过 240 是整个磁盘号。所以主要/次要 8/16 表示整个磁盘 /dev/sdb 和 8/17 是 /dev/sdb1的第一个分区的设备文件。数字 8/34 将是 /dev/sdc2。

|

||||

|

||||

在上面列表中的tty设备文件是通过从tty0到tty63的编号更简单一些。

|

||||

|

||||

Kernel.org上的[Linux Allocated Devices][5]文件是设备类型和主要和次要编号分配的正式注册表。 它可以帮助您了解所有当前定义的设备的主要/次要号码。

|

||||

|

||||

### 设备文件乐趣

|

||||

|

||||

让我们花几分钟时间,执行几个有趣的,实验将说明Linux设备文件的强大和灵活性。 大多数Linux发行版都有1到7多个虚拟控制台,可用于使用shell接口登录到本地控制台会话。 可以使用Ctrl-Alt-F1(对于控制台1),Ctrl-Alt-F2(对于控制台2)等组合键可以访问这些。

|

||||

|

||||

请按 Ctrl-Alt-F2 切换到控制台 2。在某些发行版,登录信息包括与此控制台关联的tty设备,但许多人不知道。它应该是 tty2,因为你是在控制台 2 中。

|

||||

|

||||

以非root用户身份登录。 然后你可以使用谁是我的命令(译者注:就是命令“who”)。是的,就像这样,用空格来确定哪个tty设备连接到这个控制台。

|

||||

|

||||

在我们实际执行此实验之前,看看在 /dev中的 tty2 和 tty3 的设备列表

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

ls -l /dev/tty[23]

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

将有大量的 tty 设备定义,但我们不关心他们中的大多数,只注意 tty2 和 tty3 上的设备。 作为设备文件,他们没什么特别之处。他们都只是字符类型设备。我们将使用这些设备进行此实验。 tty2设备连接到虚拟控制台2,tty3设备连接到虚拟控制台3。

|

||||

|

||||

按 Ctrl-Alt-f2 键以返回到控制台 2。字符串"Hello world"(没有引号) 将显示在控制台 2。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

echo "Hello world" > /dev/tty2

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

该实验也可以使用GUI桌面上的终端仿真器来执行。 桌面上的终端会话在 /dev 中使用伪终端设备,如 /dev/pts/1。 使用 Konsole 或 Xterm 打开两个终端会话。 确定它们连接到哪些伪终端,并使用一个向另一个发送消息。

|

||||

|

||||

现在继续实验,使用 cat 命令在不同的终端上显示 /etc/fstab 文件。

|

||||

|

||||

另一个有趣的实验是使用cat命令将文件直接打印到打印机。 假设您的打印机设备是/ dev / usb / lp0,并且您的打印机可以直接打印PDF文件,以下命令将在您的打印机上打印PDF文件test.pdf。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

cat test.pdf > /dev/usb/lp0

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

/dev目录包含一些非常有趣的设备文件,这些文件是硬件的入口,人们通常不认为这是硬盘驱动器或显示器之类的设备。 例如,系统存储器RAM不是通常被认为是“设备”的东西,而/ dev / mem是通过其可以实现对存储器的直接访问的门户。 下面的例子有一些有趣的结果。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

dd if=/dev/mem bs=2048 count=100

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The **dd** command above provides a bit more control than simply using the **cat**command to dump all of a system's memory. It provides the ability to specify how much data is read from /dev/mem and would also allow me to specify the point at which to start reading data from memory. Although some memory was read, the kernel responded with the following error that I found in /var/log/messages.

|

||||

|

||||

上面的**dd**命令提供比简单地使用**cat**命令转储所有系统的内存提供了更多的控制。 它提供了指定从 /dev/mem 读取多少数据的能力,并且还允许我指定开始从存储器读取数据的点。 虽然一些内存被读取,内核响应我在 /var/log/messages中发现的以下错误

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

Nov 14 14:37:31 david kernel: usercopy: kernel memory exposure attempt detected from ffff9f78c0010000 (dma-kmalloc-512) (2048 bytes)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

这个错误意味着内核正在通过保护属于其他进程的内存来完成它的工作,这正是它应该工作的方式。 所以,虽然可以使用 /dev/mem 来显示存储在 RAM 内存中的数据,但是访问大多数内存空间是受保护的并且会导致错误。 只有由内核内存管理器分配给运行**dd**命令的BASH shell的虚拟内存才可以访问,而不会导致错误。 抱歉,但你不能在不属于你的内存监听,除非你发现了一个漏洞利用。

|

||||

|

||||

/dev中还有一些非常有趣的设备文件。 设备文件null,zero,random和urandom不与任何物理设备相关联。

|

||||

|

||||

例如,空设备/dev/null可以用作来自shell命令或程序的输出重定向的目标,以便它们不显示在终端上。 我经常在我的BASH脚本中使用这个,以防止向用户展示可能会让他们感到困惑的输出。(译者注:作者怕大家看不懂,解释了一下) /dev/null 设备可用于产生一个空字符串。 使用如下所示的dd命令查看/dev/null设备文件的一些输出。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

# dd if=/dev/null bs=512 count=500 | od -c

|

||||

0+0 records in

|

||||

0+0 records out

|

||||

0 bytes copied, 1.5885e-05 s, 0.0 kB/s

|

||||

0000000

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

注意,因为空字符什么也没有所以确实没有可见的输出。 注意字节计数。

|

||||

|

||||

/ dev / random和/ dev / urandom设备也很有趣。 正如他们的名字所暗示的,它们都产生随机输出,而不仅仅是数字,而是任何和所有字节组合。 / dev / urandom设备产生确定性的随机输出并且非常快。 这意味着输出由算法确定,并使用种子字符串作为起点。 结果,如果原始种子是已知的,则黑客可以再现输出,尽管非常困难。 使用命令 **cat /dev/urandom** 可以查看典型输出. 你可以使用 Ctrl-c 去退出.

|

||||

|

||||

/dev/random设备文件生成非确定性随机输出,但它产生的输出更慢。 该输出不是由依赖于先前数字的算法确定的,而是响应于击键和鼠标移动而产生的。 这种方法使得复制特定系列的随机数要困难得多。使用 **cat **命令去查看一些来自/dev/random 设备文件输出。尝试移动鼠标以查看它如何影响输出。

|

||||

|

||||

正如其名字所暗示的,/ dev / zero设备文件产生一个无止境的零字符串作为输出。 注意,这些是八进制零,而不是ASCII字符零(0)。 使用如下所示的 **dd** 查看/dev/zero设备文件中的一些输出

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

# dd if=/dev/zero bs=512 count=500 | od -c

|

||||

0000000 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0 \0

|

||||

*

|

||||

500+0 records in

|

||||

500+0 records out

|

||||

256000 bytes (256 kB, 250 KiB) copied, 0.00126996 s, 202 MB/s

|

||||

0764000

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

请注意,此命令的字节计数不为零。

|

||||

|

||||

### 创建设备文件

|

||||

|

||||

在过去,在/dev 中的设备文件都是在安装时创建的,导致一个目录中可能几乎所有的设备文件,尽管大多数永远不会使用。 在不太可能发生的情况下,需要新的设备文件或意外删除并需要重新创建 **mknod** 程序可手动创建设备文件。 你必须知道的是设备主要和次要号码。

|

||||

|

||||

CentOS and RHEL 6 and 7, 以及Fedora的所有版本回到至少与Fedora 15一样,使用较新的创建设备文件的方法。 所有设备文件都是在引导时创建的。 此功能是可能的,因为udev设备管理器检测到设备的添加和删除发生时。 这允许在主机启动和运行时的真正的动态即插即用功能。 它还在引导时执行相同的任务,通过在引导过程的早期检测系统上安装的所有设备。 [Linux.com][6] 有很棒的 [udev 描述][7].

|

||||

|

||||

回到你在/ dev中的文件列表,注意文件的日期和时间。 所有这些都是在上次启动时创建的。 您可以使用验证**uptime** 或者 **last 命令。在上面的设备列表中,所有这些文件都是在11月7日上午7:06创建的,这是我最后一次启动系统。

|

||||

|

||||

当然, **mknod** 命令仍然可用, 但新的 **MAKEDEV** (是的,所有大写,在我看来是违背Linux哲学使用所有小写命令名) 命令提供了一个更容易的界面,用于创建设备文件,如果需要的话。 在当前版本的Fedora或CentOS 7中,默认情况下不安装MAKEDEV命令; 它安装在CentOS 6.您可以使用YUM或DNF来安装MAKEDEV包。

|

||||

|

||||

### 结尾

|

||||

|

||||

有趣的是,我需要创建一个设备文件已经很长时间了。 然而,最近我有一个有趣的情况,其中一个通常使用的设备文件没有创建,我不得不创建它。 我从来没有与该设备有任何问题。所以造成丢失的设备文件的情况仍然可以发生,知道如何处理它可能很重要。

|

||||

|

||||

我所没有涵盖的你可能会遇到的不同类型的设备文件。 这些信息在所引用的资源中有大量的细节信息是可用的。 我希望我已经给你一些基本的了解这些文件的功能和工具,让你自己探索更多。

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://opensource.com/article/16/11/managing-devices-linux

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[David Both][a]

|

||||

译者:[erlinux](http://www.itxdm.me)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 组织编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:https://opensource.com/users/dboth

|

||||

[1]:https://opensource.com/life/15/9/everything-is-a-file

|

||||

[2]:https://opensource.com/life/16/10/introduction-linux-filesystems

|

||||

[3]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Device_file

|

||||

[4]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Device_file

|

||||

[5]:https://www.kernel.org/doc/Documentation/devices.txt

|

||||

[6]:https://www.linux.com/

|

||||

[7]:https://www.linux.com/news/udev-introduction-device-management-modern-linux-system

|

||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user