mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-04-17 03:30:39 +08:00

20140819-2 选题

This commit is contained in:

parent

2898ef3867

commit

a079157ebb

148

sources/talk/20140819 Top 4 Linux download managers.md

Normal file

148

sources/talk/20140819 Top 4 Linux download managers.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,148 @@

|

||||

Top 4 Linux download managers

|

||||

================================================================================

|

||||

**Improve and better manage your web downloads for mirroring, mass grabs or just better control over your files**

|

||||

|

||||

Download managers seem to be old news these days, but there are still some excellent uses for them. We compare the top four of them on Linux.

|

||||

|

||||

### [uGet][1] ###

|

||||

|

||||

Advertised as lightweight and full- featured like a majority of other Linux apps, uGet can handle multi- threaded streams, includes filters and can integrate with an undefined selection of web browsers. It’s been around for over ten years now, starting out as UrlGet, and can also run on Windows.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

uGet is actually very full-featured, with a lot of the kind of functions that advanced torrent clients use

|

||||

|

||||

#### Interface ####

|

||||

|

||||

uGet reminds us of any number of torrent client interfaces, with categories for Active, Finished, Paused and so on for the different downloads. Although there is a lot of information to take in, it’s all presented very cleanly and clearly. The main downloading controls are easy to access, with more advanced ones alongside them.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Integration ####

|

||||

|

||||

While it can see into the clipboard for URLs, uGet doesn’t natively integrate into browsers like Chromium and Firefox. Still, there are add-ons for both these browsers that allow them to connect to uGet: Firefox via FlashGot and Chromium with a dedicated plug-in. Not ideal, but good enough.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Features ####

|

||||

|

||||

uGet’s maturity affords it a range of features, including advanced scheduling to switch downloading on and off, batch download via the clipboard and the ability to change which file types it looks for in the clipboard. There are plug-in options, but not a huge amount.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Availability ####

|

||||

|

||||

While it’s also available in most major distro repos, the uGet website includes regularly updated binaries for a variety of popular distributions as well as easily accessible source code. It runs on GTK 3+ so it has a smaller footprint in some desktop environments than others, although we’d say it’s worth the extra dependancies in KDE or other Qt desktops.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Overall ####

|

||||

|

||||

8/10

|

||||

|

||||

We very much like uGet – its wide variety of features and popularity have allowed it to develop quite a lot to be an all-encompassing solution to download management, with some decent integration with Linux browsers.

|

||||

|

||||

### [KGet][2] ###

|

||||

|

||||

KDE’s own download manager seems to have been originally designed to work with Konqueror, the KDE web browser. It comes with the kind of features we’re looking for in this test: control of multiple downloads and the ability to run a checksum alongside the downloaded product.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

You need to manually activate the ability to keep an eye on the clipboard for links

|

||||

|

||||

#### Interface ####

|

||||

|

||||

As expected of a KDE app, KGet fits the aesthetic style of the desktop environment with similar icons and curves throughout. It’s quite a simple design as well, with only the most necessary functions available on the main toolbars and a minimal view of the current downloads.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Integration ####

|

||||

|

||||

KGet natively integrates with KDE’s Konqueror browser, although it’s not the most popular. Support for it in Firefox is done via FlashGot as usual, but there’s no real way to do it in Chromium. You can turn on a feature that asks if you want to download copied URLs, however it doesn’t parse the clipboard very well and sometimes wants to download text.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Features ####

|

||||

|

||||

The selection of features available are not that high. No scheduling, no batch operations and generally an almost bare-minimum amount of downloading features. The clipboard-scanning feature is a nice idea but it’s a bit buggy. It’s a little weird as the Settings menu looks like it’s designed to have more settings and options.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Availability ####

|

||||

|

||||

While it doesn’t come by default with a KDE install, it is available for any distro that supports KDE. It does need a few KDE libraries to run though, and it’s a bit tricky to find the source code. There isn’t a selection of binaries that you can use with a few distros either.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Overall ####

|

||||

|

||||

6/10

|

||||

|

||||

KGet doesnt really offer users a huge amount more than the download manager in the majority of popular browsers, although at least you can use it while the browsers are otherwise turned off.

|

||||

|

||||

### [DownThemAll!][3] ###

|

||||

|

||||

DownThemAll, being somewhat platform-independent, comes to Linux by way of Firefox as an add- on. This limits it somewhat to use with only Firefox, however as one of the most popular browsers in the world its tighter integration may be just what some are looking for in a download manager.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

There are actually a whole lot of options available for DownThemAll! that make it very flexible

|

||||

|

||||

#### Interface ####

|

||||

|

||||

Part of the integration in Firefox allows DownThemAll! to slot into the standard aesthetic of the browser, with right-clicking bringing up options alongside the normal downloading ones. The extra dialog menus are generally themed after Firefox as well, while the main download window is clean and based on its own design

|

||||

|

||||

#### Integration ####

|

||||

|

||||

It doesn’t integrate system-wide but its ability to camouflage itself with Firefox makes it seem like an extra part of the original browser. It can also run alongside the normal downloader if you want, and can find specific link types on a webpage with little manual filtering, and no need for copy and pasting.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Features ####

|

||||

|

||||

With the ability to control how many downloads can happen at once, limit bandwidth when not idle and advanced auto or manual filtering, DownThemAll! is full of excellent features that aid mass downloading. The One Click function also allows it to very quickly start downloads to a pre- determined folder faster than normal download functions.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Availability ####

|

||||

|

||||

Firefox is available on just about every distro and other operating system around, which makes DownThemAll! just as prolific. Unfortunately this is a double-edged sword, as Firefox may not be your browser of choice. It also adds a little weight to the browser, which isn’t the lightest to begin with.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Overall ####

|

||||

|

||||

7/10

|

||||

|

||||

DownThemAll! is excellent and if you use Firefox you may not need to use anything else. Not everyone uses Firefox as their preferred browser though, and it needs to be left on for the manager to start running.

|

||||

|

||||

### [Steadyflow][4] ###

|

||||

|

||||

Easily available in Ubuntu and some Debian-based distros, Steadyflow may be limited in terms of where you can get it but it’s got a reputation in some circles as one of the better managers available for any distro. It can read the clipboard for URLs, use GNOME’s preset proxies and has many other features.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The settings in Steady flow are extremely limiting and somewhat difficult to access

|

||||

|

||||

#### Interface ####

|

||||

|

||||

Steadyflow is quite simple in appearance with a pleasant, clean interface that doesn’t clutter the download window. The dialog for adding downloads is simple enough, with basic options for how to treat it and where the file should live. It’s nothing we can really complain about, although it does remind us of the lack of features in the app.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Integration ####

|

||||

|

||||

Reading copied URLs is as standard and there’s a plug-in for Chromium to integrate with that. Again, you can use FlashGot to link it up to Firefox if that’s your preferred browser. You can’t really edit what it parses from the clipboard though and there’s no batch ability like in uGet and DownThemAll!

|

||||

|

||||

#### Features ####

|

||||

|

||||

Extremely lacking in features and the Options menu is very limited as well. The Pause and Resume function also doesn’t seem to work – a basic part of any browser’s file download features. Still, notifications and default action on finished files can be edited, along with an option to run a script once downloads are finished.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Availability ####

|

||||

|

||||

Only available on Ubuntu and there’s no easy way to get the source code for the app either. This means while it’s easily obtainable on all Ubuntu- based distros, it’s limited to these types of distros. As it’s not even the best download manager available on Linux, that shouldn’t be too big of a concern.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Overall ####

|

||||

|

||||

5/10

|

||||

|

||||

Frankly, not that good. With very basic options and limited to only working on Ubuntu, Steadyflow doesn’t do enough to differentiate itself from the standard downloading options you’ll get on your web browser.

|

||||

|

||||

### And the winner is… ###

|

||||

|

||||

#### uGet ####

|

||||

|

||||

In this test we’ve proven that there is a place for download managers on modern computers, even if the better ones have cribbed from the torrent clients that seem to have usurped them. While torrenting may be a more effective way for some, with ISPs getting wiser to torrent traffic some people may get better results with a good download manager. Not only are transfer caps imposed by most major ISPs, some are even beginning to slow- down or even block torrent traffic in peak hours – even legal traffic such as distro ISOs and other free software are throttled.

|

||||

|

||||

Steadyflow seems to be a very popular solution for this, but our usage and tests showed an underdeveloped and weak product. The much older uGet was the star of the show, with an amazing selection of features that can aid in downloading single items or filtering through an entire webpage for relevant items to grab. The same goes for DownThemAll!, the excellent Firefox add-on that, while stuck with Firefox, has just about the same level of features, albeit with better integration.

|

||||

|

||||

If you’re choosing between the two it really comes down to what your preferred browser is and whether you need to have downloads and uploads going around the clock. DownThemAll! requires Firefox running, whereas uGet runs on its own, saving a lot of resources and electricity in the process – obviously this makes uGet a much better prospect for 24-hour data transferring and it really isn’t a major hassle to set up big batch downloads, or even just get the download information from your browser.

|

||||

|

||||

Give download managers another chance. You will not be disappointed with the results.

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: http://www.linuxuser.co.uk/reviews/top-4-linux-download-managers

|

||||

|

||||

作者:Rob Zwetsloot

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创翻译,[Linux中国](http://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[1]:http://bit.ly/1mx4Uwz

|

||||

[2]:http://bit.ly/1lilqU9

|

||||

[3]:http://bit.ly/1lilqU9

|

||||

[4]:http://bit.ly/1lilymS

|

||||

135

sources/tech/20140819 Build a Raspberry Pi Arcade Machine.md

Normal file

135

sources/tech/20140819 Build a Raspberry Pi Arcade Machine.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,135 @@

|

||||

Build a Raspberry Pi Arcade Machine

|

||||

================================================================================

|

||||

**Relive the golden majesty of the 80s with a little help from a marvel of the current decade.**

|

||||

|

||||

### WHAT YOU’LL NEED ###

|

||||

|

||||

- Raspberry Pi w/4GB SD-CARD.

|

||||

- HDMI LCD monitor.

|

||||

- Games controller or…

|

||||

- A JAMMA arcade cabinet.

|

||||

- J-Pac or I-Pac.

|

||||

|

||||

The 1980s were memorable for many things; the end of the cold war, a carbonated drink called Quatro, the Korg Polysix synthesiser and the Commodore 64. But to a certain teenager, none of these were as potent, or as perhaps familiarly illicit, as the games arcade. Enveloped by cigarette smoke and a barrage of 8-bit sound effects, they were caverns you visited only on borrowed time: 50 pence and a portion of chips to see you through lunchtime while you honed your skills at Galaga, Rampage, Centipede, Asteroids, Ms Pacman, Phoenix, R-Rype, Donkey Kong, Rolling Thunder, Gauntlet, Street Fighter, Outrun, Defender… The list is endless.

|

||||

|

||||

These games, and the arcade machine form factor that held them, are just as compelling today as they were 30 years ago. And unlike the teenage version of yourself, you can now play many of them without needing a pocket full of change, finally giving you an edge over the rich kids and their endless ‘Continues’. It’s time to build your own Linux-based arcade machine and beat that old high score.

|

||||

|

||||

We’re going to cover all the steps required to turn a cheap shell of an arcade machine into a Linux-powered multi-platform retro games system. But that doesn’t mean you’ve got to build the whole system at the same scale. You could, for example, forgo the large, heavy and potentially carcinogenic hulk of the cabinet itself and stuff the controlling innards into an old games console or an even smaller case. Or you could just as easily forgo the diminutive Raspberry Pi and replace the brains of your system with a much more capable Linux machine. This might make an ideal platform for SteamOS, for example, and for playing some of its excellent modern arcade games.

|

||||

|

||||

Over the next few pages we’ll construct a Raspberry Pi-based arcade machine, but you should be able to see plenty of ideas for your own projects, even if they don’t look just like ours. And because we’re building it on the staggeringly powerful MAME, you’ll be able to get it running on almost anything.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

We did this project before the model B+ came out. It should all work exactly the same on the newer board, and you should be able to get by without a powered USB Hub (click for larger).

|

||||

|

||||

### Disclaimer ###

|

||||

|

||||

One again we’re messing with electrical components that could cause you a shock. Make sure you get any modifications you make checked by a qualified electrician. We don’t go into any details on how to obtain games, but there are legal sources such as old games releases and newer commercial titles based on the MAME emulator.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Step1: The Cabinet ####

|

||||

|

||||

The cabinet itself is the biggest challenge. We bought an old two-player Bubble Bobble machine from the early 90s from eBay. It cost £220 delivered in the back of an old estate car. The prices for cabinets like these can vary. We’ve seen many for less than £100. At the other end of the scale, people pay thousands for machines with original decals on the side.

|

||||

|

||||

There are two major considerations when it comes to buying a cabinet. The first is the size: These things are big and heavy. They take up a lot of space and it takes at least two people to move them around. If you’ve got the money, you can buy DIY cabinets or new smaller form-factors, such as cabinets that fit on tables. And cocktail cabinets can be easier to fit, too.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Cabinets can be cheap, but they’re heavy. Don’t lift them on your own. Older ones may need some TLC, such as are-spray and some repair work(click for larger).

|

||||

|

||||

One of the best reasons for buying an original cabinet, apart from getting a much more authentic gaming experience, is being able to use the original controls. Many machines you can buy on eBay will be for two concurrent players, with two joysticks and a variety of buttons for each player, plus the player one and player two controls. For compatibility with the widest number of games, we’d recommend finding a machine with six buttons for each player, which is a common configuration. You might also want to look into a panel with more than two players, or one with space for other input controllers, such as an arcade trackball (for games like Marble Madness), or a spinner (Arkanoid). These can be added without too much difficulty later, as modern USB devices exist.

|

||||

|

||||

Controls are the second, and we’d say most important consideration, because it’s these that transfer your twitches and tweaks into game movement. What you need to consider for when buying a cabinet is something called JAMMA, an acronym for Japan Amusement Machinery Manufacturers. JAMMA is a standard in arcade machines that defines how the circuit board containing the game chips connects to the game controllers and the coin mechanism. It’s an interface conduit for all the cables coming from the buttons and the joysticks, for two players, bringing them into a standard edge connector. The JAMMA part is the size and layout of this connector, as it means the buttons and controls will be connected to the same functions on whichever board you install so that the arcade owner would only have to change the cabinet artwork to bring in new players.

|

||||

|

||||

But first, a word of warning: the JAMMA connector also carries the 12V power supply, usually from a power unit installed in most arcade machines. We disconnecting the power supply completely to avoid damaging anything with a wayward short-circuit or dropped screwdriver. We don’t use any of the power connectors in any further stage of the tutorial.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

#### Step 2: J-PAC ####

|

||||

|

||||

What’s brilliant is that you can buy a device that connects to the JAMMA connector inside your cabinet and a USB port on your computer, transforming all the buttons presses and keyboard movements into (configurable) keyboard commands that you can use from Linux to control any game you wish. This device is called the J-Pac ([www.ultimarc.com/jpac.html][1] – approximately £54).

|

||||

|

||||

Its best feature isn’t the connectivity; it’s the way it handles and converts the input signals, because it’s vastly superior to a standard USB joystick. Every input generates its own interrupt, and there’s no limit to the number of simultaneous buttons and directions you can press or hold down. This is vital for games like Street Fighter, because they rely on chords of buttons being pressed simultaneously and quickly, but it’s also essential when delivering the killing blow to cheating players who sulk and hold down all their own buttons. Many other controllers, especially those that create keyboard inputs, are restricted by their USB keyboard controllers to six inputs and a variety of Alt, Shift and Ctrl hacks. The J-Pac can also be connected to a tilt sensor and even some coin mechanisms, and it works in Linux without any pre-configuration.

|

||||

|

||||

Another option is a similar device called an I-Pac. It does the same thing as the J-Pac, only without the JAMMA connector. That means you can’t connect your JAMMA controls, but it does mean you can design your own controller layout and wire each control to the I-Pac yourself. This might be a little ambitious for a first project, but it’s a route that many arcade aficionados take, especially when they want to design a panel for four players, or one that incorporates many different kinds of controls. Our approach isn’t necessarily one we’d recommend, but we re-wired an old X-Arcade Tankstick control panel that suffered from input contention, replaced the joysticks and buttons with new units and connected it to a new JAMMA harness, which is an excellent way of buying all the cables you need plus the edge connector for a low price (£8).

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Our J-Pac in situ. The blue and red wires on the right connect to the extra 1- and 2-player buttons on our cabinet (click for larger).

|

||||

|

||||

Whether you choose an I-Pac or a J-Pac, all the keys generated by both devices are the default values for MAME. That means you won’t have to make any manual input changes when you start to run the emulator. Player 1, for example, creates cursor up, down, left and right as well as left Ctrl, left ALT, Space and left Shift for fire buttons 1–4. But the really useful feature, for us, is the two-button shortcuts. While holding down the player 1 button, you can generate the P key to pause the game by pulling down on the player 1 joystick, adjust the volume by pressing up and enter MAME’s own configuration menu by pushing right. These escape codes are cleverly engineered to not get in the way of playing games, as they’re only activated when holding down the Player 1 button, and they enable you to do almost anything you need to from within a running game. You can completely reconfigure MAME, for example, using its own menus, and change input assignments and sensitivity while playing the game itself.

|

||||

|

||||

Finally, holding down Player 1 and then pressing Player 2 will quit MAME, which is useful if you’re using a launch menu or MAME manager, as these manage launching games automatically, and let you get on with playing another game as quickly as possible.

|

||||

|

||||

We took a rather cowardly route with the screen, removing the original, bulky and broken CRT that came with the cabinet and replacing it with a low-cost LCD monitor. This approach has many advantages. First, the screen has HDMI, so it will interface with a Raspberry Pi or a modern graphics card without any difficulty. Second, you don’t have to configure the low-frequency update modes required to drive an arcade machine’s screen, nor do you need the specific graphics hardware that drives it. And third, this is the safest option because an arcade machine’s screen is often unprotected from the rear of a case, leaving very high voltages inches away from your hands. That’s not to say you shouldn’t use a CRT if that’s the experience you’re after – it’s the most authentic way to get the gaming experience you’re after, but we’ve fined-tuned the CRT emulation enough in software that we’re happy with the output, and we’re definitely happier not to be using an ageing CRT.

|

||||

|

||||

You might also want to look into using an older LCD with a 4:3 aspect ratio, rather than the widescreen modern options, because 4:3 is more practical for playing both vertical and horizontal games. A vertical shooter such as Raiden, for example, will have black bars on either side of the gaming area if you use a widescreen monitor. Those black bars can be used to display the game instructions, or you could rotate the screen 90 degrees so that every pixel is used, but this is impractical unless you’re only going to play vertical games or have easy access to a rotating mount.

|

||||

|

||||

Mounting a screen is also important. If you’ve removed a CRT, there’s nowhere for an LCD to go. Our solution was to buy some MDF cut to fit the space where the CRT was. This was then screwed into position and we fitted a cheap VESA mounting plate into the centre of the new MDF. VESA mounts can be used by the vast majority of screens, big and small. Finally, because our cabinet was fronted with smoked glass, we had to be sure both the brightness and contrast were set high enough.

|

||||

|

||||

### Step 3: Installation ###

|

||||

|

||||

With the large hardware choices now made, and presumably the cabinet close to where you finally want to install it, putting the physical pieces together isn’t that difficult. We safely split the power input from the rear of the cabinet and wired a multiple socket into the space at the back. We did this to the cable after it connects to the power switch.

|

||||

|

||||

Nearly all arcade cabinets have a power switch on the top-right surface, but there’s usually plenty of cable to splice into this at a lower point in the cabinet, and it meant we could use normal power connectors for our equipment. Our cabinet has a fluorescent tube, used to backlight the top marquee on the machine, connected directly to the power, and we were able to keep this connected by attaching a regular plug. When you turn the power on from the cabinet switch, power flows to the components inside the case – your Raspberry Pi and screen will come on, and all will be well with the world.

|

||||

|

||||

The J-Pac slides straight into the JAMMA interface, but you may also have to do a little manual wiring. The JAMMA standard only supports up to three buttons for each player (although many unofficially support four), while the J-Pac can handle up to six buttons. To get those extra buttons connected, you need to connect one side of the button’s switch to GND fed from the J-Pac with the other side of the switch going into one of the screw-mounted inputs in the side of the J-Pac. These are labelled 1SW4, 1SW5, 1SW6, 2SW4, 2SW5 and 2SW6. The J-Pac also includes passthrough connections for audio, but we’ve found this to be incredibly noisy. Instead, we wired the speaker in our cabinet to an old SoundBlaster amplifier and connected this to the audio outputs on the Raspberry Pi. You don’t want audio to be pristine, but you do want it to be loud enough.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Our Raspberry Pi is now connected to the J-Pac on the left and both the screen and the USB hub (click for larger).

|

||||

|

||||

The J-Pac or I-Pac then connects to your PC or Raspberry Pi using a PS2-to-USB cable, which should also be used to connect to a PS2 port on your PC directly. There is an additional option to use an old PS2 connector, if your PC is old enough to have one, but we found in testing that the USB performance is identical. This won’t apply to the PS2-less Raspberry Pi, of course, and don’t forget that the Pi will also need powering. We always recommend doing so from a compatible powered hub, as a lack of power is the most common source of Raspberry Pi errors. You’ll also need to get networking to your Raspberry Pi, either through the Ethernet port (perhaps using a powerline adaptor hidden in the cabinet), or by using a wireless USB device. Networking is essential because it enables you to reconfigure your PI while it’s tucked away within the cabinet, and it also enables you to change settings and perform administration tasks without having to connect a keyboard or mouse.

|

||||

|

||||

> ### Coin Mechanism ###

|

||||

|

||||

> In the emulation community, getting your coin mechanism to work with your emulator was often considered a step too close to commercial production. It meant you could potential charge people to use your machine. Not only would this be wrong, but considering the provenance of many of the games you run on your own arcade machine, it could also be illegal. And it’s definitely against the spirit of emulation. However, we and many other devotees thinking that a working coin mechanism is another step closer to the realism of an arcade machine, and is worth the effort in recreating the nostalgia of an old arcade. There’s nothing like dropping a 10p piece into the coin tray and to hear the sound of the credits being added to the machine.

|

||||

|

||||

> It’s not actually that difficult. It depends on the coin mechanism in your arcade machine and how it sends a signal to say how many credits had been inserted. Most coin mechanisms come in two parts. The large part is the coin acceptor/validator. This is the physical side of the process that detects whether a coin is authentic, and determines its value. It does this with the help of a credit/logic board, usually attached via a ribbon cable and featuring lots of DIP switches. These switches are used to change which coins are accepted and how many credits they generate. It’s then usually as simple as finding the output switch, which is triggered with a credit, and connecting this to the coin input on your JAMMA connector, or directly onto the J-Pac. Our coin mechanism is a Mars MS111, common in the UK in the early 90s, and there’s plenty of information online about what each of the DIP switches do, as well as how to programme the controller for newer coins. We were also able to wire the 12V connector from the mechanism to a small light for behind the coin entry slot.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Step 4: Software ####

|

||||

|

||||

MAME is the only viable emulator for a project of this scale, and it now supports many thousands of different games running on countless different platforms, from the first arcade machines through to some more recent ones. It’s a project that has also spawned MESS, the multi-emulator super system, which targets platforms such as home computers and consoles from the 80s and 90s.

|

||||

|

||||

Configuring MAME could take a six-page article in itself. It’s a complex, sprawling, magnificent piece of software that emulates so many CPUs, so many sound devices, chips, controllers with so many options, that like MythTV, you never really stop configuring it.

|

||||

|

||||

But there’s an easier option, and one that’s purpose-built for the Raspberry Pi. It’s called PiMAME. This is both a distribution download and a script you can run on top of Raspbian, the Pi’s default distribution. Not only does it install MAME on your Raspberry Pi (which is useful because it’s not part of any of the default repositories), it also installs a selection of other emulators along with front-ends to manage them. MAME, for example, is a command-line utility with dozens of options. But PiMAME has another clever trick up its sleeve – it installs a simple web server that enables you to install new games through a browser connected to your network. This is a great advantage, because getting games into the correct folders is one of the trials of dealing with MAME, and it also enables you to make best use of whatever storage you’ve got connected to your Pi. Plus, PiMAME will update itself from the same script you use to install it, so keeping on top of updates couldn’t be easier. This could be especially useful at the moment, as at the time of writing the project was on the cusp of a major upgrade in the form of the 0.8 release. We found it slightly unstable in early March, but we’re sure everything will be sorted by the time you read this.

|

||||

|

||||

The best way to install PiMAME is to install Raspbian first. You can do this either through NOOBS, using a graphical tool from your desktop, or by using the dd command to copy the contents of the Raspbian image directly onto your SD card. As we mentioned in last month’s BrewPi tutorial, this process has been documented many times before, so we won’t waste the space here. Just install NOOBS if you want the easy option, following the instructions on the Raspberry Pi site. With Raspbian installed and running, make sure you use the configuration tool to free the space on your SD card, and that the system is up to date (sudo apt-get update; sudo apt-get upgrade). You then need to make sure you’ve got the git package already installed. Any recent version of Raspbian will have installed git already, but you can check by typing sudo apt-get install git just to check.

|

||||

|

||||

You then have to type the following command to clone the PiMAME installer from the project’s GitHub repository:

|

||||

|

||||

git clone https://github.com/ssilverm/pimame_installer

|

||||

|

||||

After that, you should get the following feedback if the command works:

|

||||

|

||||

Cloning into ‘pimame_installer’...

|

||||

remote: Reusing existing pack: 2306, done.

|

||||

remote: Total 2306 (delta 0), reused 0 (delta 0)

|

||||

Receiving objects: 100% (2306/2306), 4.61 MiB | 11 KiB/s, done.

|

||||

Resolving deltas: 100% (823/823), done.

|

||||

|

||||

This command will create a new folder called ‘pimame_installer’, and the next step is to switch into this and run the script it contains:

|

||||

|

||||

cd pimame_installer/

|

||||

sudo ./install.sh

|

||||

|

||||

This command installs and configures a lot of software. The length of time it takes will depend on your internet connection, as a lot of extra packages are downloaded. Our humble Pi with a 15Mb internet connection took around 45 minutes to complete the script, after which you’re invited to restart the machine. You can do this safely by typing sudo shutdown -r now, as this command will automatically handle any remaining write operations to the SD card.

|

||||

|

||||

And that’s all there is to the installation. After rebooting your Pi, you will be automatically logged in and the PiMAME launch menu will appear. It’s a great-looking interface in version 0.8, with photos of each of the platforms supported, plus small red icons to indicate how many games you’ve got installed.This should now be navigable through your controller. If you want to make sure the controller is correctly detected, use SSH to connect to your Pi and check for the existence of **/dev/input/by-id/usb-Ultimarc_I-PAC_Ultimarc_I-PAC-event-kbd**.

|

||||

|

||||

The default keyboard controls will enable you to select what kind of emulator you want to run on your arcade machine. The option we’re most interested in is the first, labelled ‘AdvMAME’, but you might also be surprised to see another MAME on offer, MAME4ALL. MAME4ALL is built specifically for the Raspberry Pi, and takes an old version of the MAME source code so that the performance of the ROMS that it does support is optimal. This makes a lot of sense, because there’s no way your Pi is going to be able to play anything too demanding, so there’s no reason to belabour the emulator with unneeded compatibility. All that’s left to do now is get some games onto your system (see the boxout below), and have fun!

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: http://www.linuxvoice.com/arcade-machine/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Ben Everard][a]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创翻译,[Linux中国](http://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:http://www.linuxvoice.com/author/ben_everard/

|

||||

[1]:http://www.ultimarc.com/jpac.html

|

||||

105

sources/tech/20140819 How to Encrypt Email in Linux.md

Normal file

105

sources/tech/20140819 How to Encrypt Email in Linux.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,105 @@

|

||||

How to Encrypt Email in Linux

|

||||

================================================================================

|

||||

|

||||

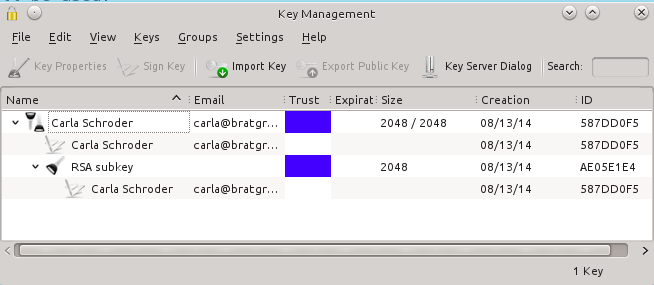

Kgpg provides a nice GUI for creating and managing your encryption keys.

|

||||

|

||||

If you've been thinking of encrypting your email, it is a rather bewildering maze to sort through thanks to the multitude of email services and mail clients. There are two levels of encryption to consider: SSL/TLS encryption protects your login and password to your mailserver. [GnuPG][1] is the standard strong Linux encryption tool, and it encrypts and authenticates your messages. It is best if you manage your own GPG encryption and not leave it up to third parties, which we will discuss in a moment.

|

||||

|

||||

Encrypting messages still leaves you vulnerable to traffic analysis, as message headers must be in the clear. So that necessitates yet another tool such as the [Tor network][2] for hiding your Internet footprints. Let's look at various mail services and clients, and the pitfalls and benefits therein.

|

||||

|

||||

### Forget Webmail ###

|

||||

|

||||

If you use GMail, Yahoo, Hotmail, or another Web mail provider, forget about it. Anything you type in a Web browser is vulnerable to JavaScript attacks, and whatever mischiefs the service provider engages in. GMail, Yahoo, and Hotmail all offer SSL/TLS encryption to protect your messages from wiretapping. But they offer no protections from their own data-mining habits, so they don't offer end-to-end encryption. Yahoo and Google both claim they're going to roll out end-to-end encryption next year. Color me skeptical, because they will wither and die if anything interferes with the data-mining that is their core business.

|

||||

|

||||

There are various third-party email security services such as [Virtru][3] and [SafeMess][4] that claim to offer secure encryption for all types of email. Again I am skeptical, because whoever holds your encryption keys has access to your messages, so you're still depending on trust rather than technology.

|

||||

|

||||

Peer messaging avoids many of the pitfalls of using centralized services. [RetroShare][5] and [Bitmessage][6] are two popular examples of this. I don't know if they live up to their claims, but the concept certainly has merit.

|

||||

|

||||

What about Android and iOS? It's safest to assume that the majority of Android and iOS apps are out to get you. Don't take my word for it-- read their terms of service and examine the permissions they require to install on your devices. And even if their terms are acceptable when you first install them, unilateral TOS changes are industry standard, so it is safest to assume the worst.

|

||||

|

||||

### Zero Knowledge ###

|

||||

|

||||

[Proton Mail][7] is a new email service that claims zero-knowledge message encryption. Authentication and message encryption are two separate steps, Proton is under Swiss privacy laws, and they do not log user activity. Zero knowledge encryption offers real security. This means that only you possess your encryption keys, and if you lose them your messages are not recoverable.

|

||||

|

||||

There are many encrypted email services that claim to protect your privacy. Read the fine print carefully and look for red flags such as limited user data collection, sharing with partners, and cooperation with law enforcement. These indicate that they collect and share user data, and have access to your encryption keys and can read your messages.

|

||||

|

||||

### Linux Mail Clients ###

|

||||

|

||||

A standalone open source mail client such as KMail, Thunderbird, Mutt, Claws, Evolution, Sylpheed, or Alpine, set up with your own GnuPG keys that you control gives you the most protection. (The easiest way to set up more secure email and Web surfing is to run the TAILS live Linux distribution. See [Protect Yourself Online With Tor, TAILS, and Debian][8].)

|

||||

|

||||

Whether you use TAILS or a standard Linux distro, managing GnuPG is the same, so let's learn how to encrypt messages with GnuPG.

|

||||

|

||||

### How to Use GnuPG ###

|

||||

|

||||

First, a quick bit of terminology. OpenPGP is an open email encryption and authentication protocol, based on Phil Zimmerman's Pretty Good Privacy (PGP). GNU Privacy Guard (GnuPG or GPG) is the GPL implementation of OpenPGP. GnuPG uses symmetric public key cryptography. This means that you create pairs of keys: a public key that anyone can use to encrypt messages to send to you, and a private key that only you possess to decrypt them. GnuPG performs two separate functions: digitally-signing messages to prove they came from you, and encrypting messages. Anyone can read your digitally-signed messages, but only people you have exchanged keys with can read your encrypted messages. Remember, never share your private keys! Only public keys.

|

||||

|

||||

Seahorse is GNOME's graphical front-end to GnuPG, and KGpg is KDE's graphical GnuPG tool.

|

||||

|

||||

Now let's run through the basic steps of creating and managing GnuPG keys. This command creates a new key:

|

||||

|

||||

$ gpg --gen-key

|

||||

|

||||

This is a multi-step process; just answer all the questions, and the defaults are fine for most people. When you create your passphrase, write it down and keep it in a secure place because if you lose it you cannot decrypt anything. All that advice about never writing down your passwords is wrong. Most of us have dozens of logins and passwords to track, including some that we rarely use, so it's not realistic to remember all of them. You know what happens when people don't write down their passwords? They create simple passwords and re-use them. Anything you store on your computer is potentially vulnerable; a nice little notebook kept in a locked drawer is impervious to everything but a physical intrusion, if an intruder even knew to look for it.

|

||||

|

||||

I must leave it as your homework to figure out how to configure your mail client to use your new key, as every one is different. You can list your key or keys:

|

||||

|

||||

$ gpg --list-keys

|

||||

/home/carla/.gnupg/pubring.gpg

|

||||

------------------------------

|

||||

pub 2048R/587DD0F5 2014-08-13

|

||||

uid Carla Schroder (my gpg key)

|

||||

sub 2048R/AE05E1E4 2014-08-13

|

||||

|

||||

This is a fast way to grab necessary information like the location of your keys, and your key name, which is the UID. Suppose you want to upload your public key to a keyserver; this is how it looks using my example key:

|

||||

|

||||

$ gpg --send-keys 'Carla Schroder' --keyserver http://example.com

|

||||

|

||||

When you create a new key for upload to public key servers, you should also create a revocation certificate. Don't do it later-- create it when you create your new key. You can give it any arbitrary name, so instead of revoke.asc you could give it a descriptive name like mycodeproject.asc:

|

||||

|

||||

$ gpg --output revoke.asc --gen-revoke 'Carla Schroder'

|

||||

|

||||

Now if your key ever becomes compromised you can revoke it by first importing the revocation certificate into your keyring:

|

||||

|

||||

$ gpg --import ~/.gnupg/revoke.asc

|

||||

|

||||

Then create and upload a new key to replace it. Any users of your old key will be notified as they refresh their key databases.

|

||||

|

||||

You must guard your revocation certificate just as zealously as your private key. Copy it to a CD or USB stick and lock it up, and delete it from your computer. It is a plain-text key, so you could even print it on paper.

|

||||

|

||||

If you ever need a copy-and-paste key, for example on public keyrings that allow pasting your key into a web form, or if you want to post your public key on your Web site, then you must create an ASCII-armored version of your public key:

|

||||

|

||||

$ gpg --output carla-pubkey.asc --export -a 'Carla Schroder'

|

||||

|

||||

This creates the familiar plain-text public key you've probably seen, like this shortened example:

|

||||

|

||||

-----BEGIN PGP PUBLIC KEY BLOCK-----

|

||||

Version: GnuPG v1

|

||||

mQENBFPrn4gBCADeEXKdrDOV3AFXL7QQQ+i61rMOZKwFTxlJlNbAVczpawkWRC3l

|

||||

IrWeeJiy2VyoMQ2ZXpBLDwGEjVQ5H7/UyjUsP8h2ufIJt01NO1pQJMwaOMcS5yTS

|

||||

[...]

|

||||

I+LNrbP23HEvgAdNSBWqa8MaZGUWBietQP7JsKjmE+ukalm8jY8mdWDyS4nMhZY=

|

||||

=QL65

|

||||

-----END PGP PUBLIC KEY BLOCK-----

|

||||

|

||||

That should get you started learning your way around GnuPG. [The GnuPG manuals][9] have complete details on using GnuPG and all of its options.

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: http://www.linux.com/learn/tutorials/784165-how-to-encrypt-email-in-linux

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Carla Schroder][a]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创翻译,[Linux中国](http://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:http://www.linux.com/component/ninjaboard/person/3734

|

||||

[1]:http://www.openpgp.org/members/gnupg.shtml

|

||||

[2]:https://www.torproject.org/

|

||||

[3]:https://www.virtru.com/

|

||||

[4]:https://www.safemess.com/

|

||||

[5]:http://retroshare.sourceforge.net/

|

||||

[6]:http://retroshare.sourceforge.net/

|

||||

[7]:https://protonmail.ch/

|

||||

[8]:http://www.linux.com/learn/docs/718398-protect-yourself-online-with-tor-+tails-and-debian

|

||||

[9]:https://www.gnupg.org/documentation/manuals.html

|

||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user