mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-02-03 23:40:14 +08:00

Merge pull request #14989 from wxy/20181011-Exploring-the-Linux-kernel--The-secrets-of-Kconfig-kbuild

TSL:20181011 Exploring the Linux kernel The secrets of Kconfig kbuild

This commit is contained in:

commit

9030902da0

@ -1,259 +0,0 @@

|

||||

wxy applied

|

||||

|

||||

Exploring the Linux kernel: The secrets of Kconfig/kbuild

|

||||

======

|

||||

Dive into understanding how the Linux config/build system works.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The Linux kernel config/build system, also known as Kconfig/kbuild, has been around for a long time, ever since the Linux kernel code migrated to Git. As supporting infrastructure, however, it is seldom in the spotlight; even kernel developers who use it in their daily work never really think about it.

|

||||

|

||||

To explore how the Linux kernel is compiled, this article will dive into the Kconfig/kbuild internal process, explain how the .config file and the vmlinux/bzImage files are produced, and introduce a smart trick for dependency tracking.

|

||||

|

||||

### Kconfig

|

||||

|

||||

The first step in building a kernel is always configuration. Kconfig helps make the Linux kernel highly modular and customizable. Kconfig offers the user many config targets:

|

||||

| config | Update current config utilizing a line-oriented program |

|

||||

| nconfig | Update current config utilizing a ncurses menu-based program |

|

||||

| menuconfig | Update current config utilizing a menu-based program |

|

||||

| xconfig | Update current config utilizing a Qt-based frontend |

|

||||

| gconfig | Update current config utilizing a GTK+ based frontend |

|

||||

| oldconfig | Update current config utilizing a provided .config as base |

|

||||

| localmodconfig | Update current config disabling modules not loaded |

|

||||

| localyesconfig | Update current config converting local mods to core |

|

||||

| defconfig | New config with default from Arch-supplied defconfig |

|

||||

| savedefconfig | Save current config as ./defconfig (minimal config) |

|

||||

| allnoconfig | New config where all options are answered with 'no' |

|

||||

| allyesconfig | New config where all options are accepted with 'yes' |

|

||||

| allmodconfig | New config selecting modules when possible |

|

||||

| alldefconfig | New config with all symbols set to default |

|

||||

| randconfig | New config with a random answer to all options |

|

||||

| listnewconfig | List new options |

|

||||

| olddefconfig | Same as oldconfig but sets new symbols to their default value without prompting |

|

||||

| kvmconfig | Enable additional options for KVM guest kernel support |

|

||||

| xenconfig | Enable additional options for xen dom0 and guest kernel support |

|

||||

| tinyconfig | Configure the tiniest possible kernel |

|

||||

|

||||

I think **menuconfig** is the most popular of these targets. The targets are processed by different host programs, which are provided by the kernel and built during kernel building. Some targets have a GUI (for the user's convenience) while most don't. Kconfig-related tools and source code reside mainly under **scripts/kconfig/** in the kernel source. As we can see from **scripts/kconfig/Makefile** , there are several host programs, including **conf** , **mconf** , and **nconf**. Except for **conf** , each of them is responsible for one of the GUI-based config targets, so, **conf** deals with most of them.

|

||||

|

||||

Logically, Kconfig's infrastructure has two parts: one implements a [new language][1] to define the configuration items (see the Kconfig files under the kernel source), and the other parses the Kconfig language and deals with configuration actions.

|

||||

|

||||

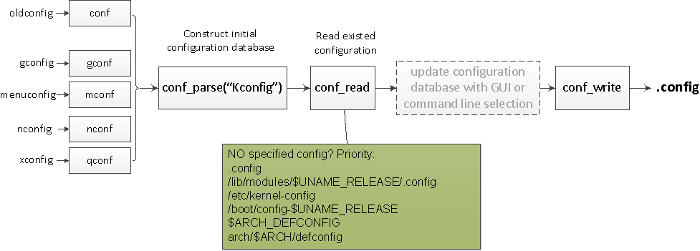

Most of the config targets have roughly the same internal process (shown below):

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Note that all configuration items have a default value.

|

||||

|

||||

The first step reads the Kconfig file under source root to construct an initial configuration database; then it updates the initial database by reading an existing configuration file according to this priority:

|

||||

|

||||

> .config

|

||||

> /lib/modules/$(shell,uname -r)/.config

|

||||

> /etc/kernel-config

|

||||

> /boot/config-$(shell,uname -r)

|

||||

> ARCH_DEFCONFIG

|

||||

> arch/$(ARCH)/defconfig

|

||||

|

||||

If you are doing GUI-based configuration via **menuconfig** or command-line-based configuration via **oldconfig** , the database is updated according to your customization. Finally, the configuration database is dumped into the .config file.

|

||||

|

||||

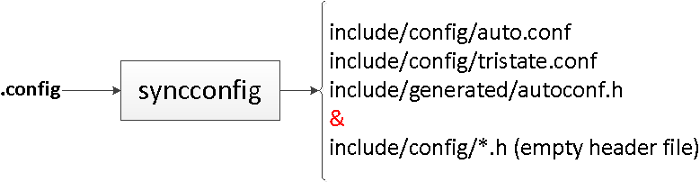

But the .config file is not the final fodder for kernel building; this is why the **syncconfig** target exists. **syncconfig** used to be a config target called **silentoldconfig** , but it doesn't do what the old name says, so it was renamed. Also, because it is for internal use (not for users), it was dropped from the list.

|

||||

|

||||

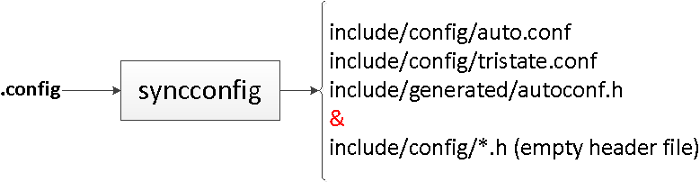

Here is an illustration of what **syncconfig** does:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

**syncconfig** takes .config as input and outputs many other files, which fall into three categories:

|

||||

|

||||

* **auto.conf & tristate.conf** are used for makefile text processing. For example, you may see statements like this in a component's makefile:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

obj-$(CONFIG_GENERIC_CALIBRATE_DELAY) += calibrate.o

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

* **autoconf.h** is used in C-language source files.

|

||||

|

||||

* Empty header files under **include/config/** are used for configuration-dependency tracking during kbuild, which is explained below.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

After configuration, we will know which files and code pieces are not compiled.

|

||||

|

||||

### kbuild

|

||||

|

||||

Component-wise building, called _recursive make_ , is a common way for GNU `make` to manage a large project. Kbuild is a good example of recursive make. By dividing source files into different modules/components, each component is managed by its own makefile. When you start building, a top makefile invokes each component's makefile in the proper order, builds the components, and collects them into the final executive.

|

||||

|

||||

Kbuild refers to different kinds of makefiles:

|

||||

|

||||

* **Makefile** is the top makefile located in source root.

|

||||

* **.config** is the kernel configuration file.

|

||||

* **arch/$(ARCH)/Makefile** is the arch makefile, which is the supplement to the top makefile.

|

||||

* **scripts/Makefile.*** describes common rules for all kbuild makefiles.

|

||||

* Finally, there are about 500 **kbuild makefiles**.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The top makefile includes the arch makefile, reads the .config file, descends into subdirectories, invokes **make** on each component's makefile with the help of routines defined in **scripts/Makefile.*** , builds up each intermediate object, and links all the intermediate objects into vmlinux. Kernel document [Documentation/kbuild/makefiles.txt][2] describes all aspects of these makefiles.

|

||||

|

||||

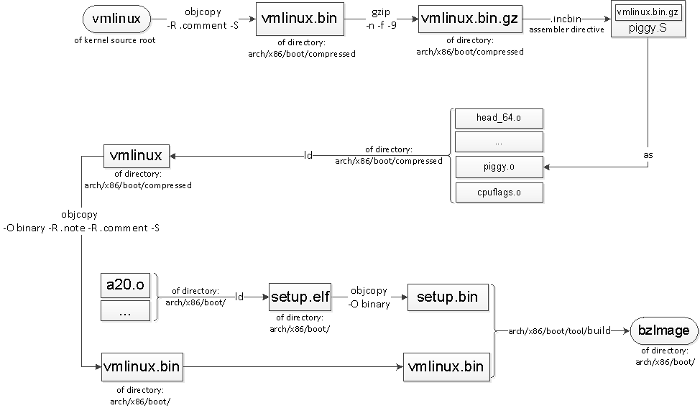

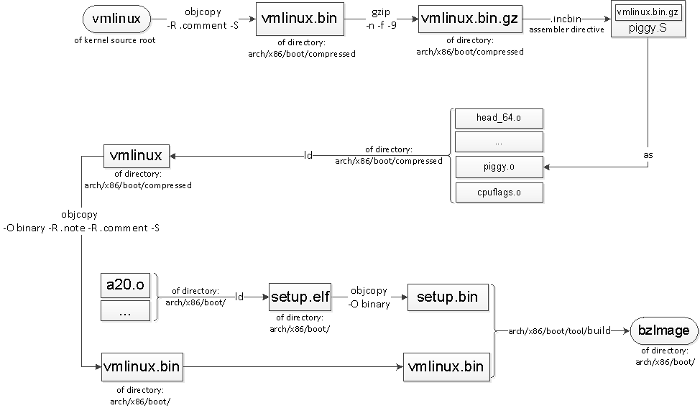

As an example, let's look at how vmlinux is produced on x86-64:

|

||||

|

||||

![vmlinux overview][4]

|

||||

|

||||

(The illustration is based on Richard Y. Steven's [blog][5]. It was updated and is used with the author's permission.)

|

||||

|

||||

All the **.o** files that go into vmlinux first go into their own **built-in.a** , which is indicated via variables **KBUILD_VMLINUX_INIT** , **KBUILD_VMLINUX_MAIN** , **KBUILD_VMLINUX_LIBS** , then are collected into the vmlinux file.

|

||||

|

||||

Take a look at how recursive make is implemented in the Linux kernel, with the help of simplified makefile code:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

# In top Makefile

|

||||

vmlinux: scripts/link-vmlinux.sh $(vmlinux-deps)

|

||||

+$(call if_changed,link-vmlinux)

|

||||

|

||||

# Variable assignments

|

||||

vmlinux-deps := $(KBUILD_LDS) $(KBUILD_VMLINUX_INIT) $(KBUILD_VMLINUX_MAIN) $(KBUILD_VMLINUX_LIBS)

|

||||

|

||||

export KBUILD_VMLINUX_INIT := $(head-y) $(init-y)

|

||||

export KBUILD_VMLINUX_MAIN := $(core-y) $(libs-y2) $(drivers-y) $(net-y) $(virt-y)

|

||||

export KBUILD_VMLINUX_LIBS := $(libs-y1)

|

||||

export KBUILD_LDS := arch/$(SRCARCH)/kernel/vmlinux.lds

|

||||

|

||||

init-y := init/

|

||||

drivers-y := drivers/ sound/ firmware/

|

||||

net-y := net/

|

||||

libs-y := lib/

|

||||

core-y := usr/

|

||||

virt-y := virt/

|

||||

|

||||

# Transform to corresponding built-in.a

|

||||

init-y := $(patsubst %/, %/built-in.a, $(init-y))

|

||||

core-y := $(patsubst %/, %/built-in.a, $(core-y))

|

||||

drivers-y := $(patsubst %/, %/built-in.a, $(drivers-y))

|

||||

net-y := $(patsubst %/, %/built-in.a, $(net-y))

|

||||

libs-y1 := $(patsubst %/, %/lib.a, $(libs-y))

|

||||

libs-y2 := $(patsubst %/, %/built-in.a, $(filter-out %.a, $(libs-y)))

|

||||

virt-y := $(patsubst %/, %/built-in.a, $(virt-y))

|

||||

|

||||

# Setup the dependency. vmlinux-deps are all intermediate objects, vmlinux-dirs

|

||||

# are phony targets, so every time comes to this rule, the recipe of vmlinux-dirs

|

||||

# will be executed. Refer "4.6 Phony Targets" of `info make`

|

||||

$(sort $(vmlinux-deps)): $(vmlinux-dirs) ;

|

||||

|

||||

# Variable vmlinux-dirs is the directory part of each built-in.a

|

||||

vmlinux-dirs := $(patsubst %/,%,$(filter %/, $(init-y) $(init-m) \

|

||||

$(core-y) $(core-m) $(drivers-y) $(drivers-m) \

|

||||

$(net-y) $(net-m) $(libs-y) $(libs-m) $(virt-y)))

|

||||

|

||||

# The entry of recursive make

|

||||

$(vmlinux-dirs):

|

||||

$(Q)$(MAKE) $(build)=$@ need-builtin=1

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The recursive make recipe is expanded, for example:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

make -f scripts/Makefile.build obj=init need-builtin=1

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This means **make** will go into **scripts/Makefile.build** to continue the work of building each **built-in.a**. With the help of **scripts/link-vmlinux.sh** , the vmlinux file is finally under source root.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Understanding vmlinux vs. bzImage

|

||||

|

||||

Many Linux kernel developers may not be clear about the relationship between vmlinux and bzImage. For example, here is their relationship in x86-64:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The source root vmlinux is stripped, compressed, put into **piggy.S** , then linked with other peer objects into **arch/x86/boot/compressed/vmlinux**. Meanwhile, a file called setup.bin is produced under **arch/x86/boot**. There may be an optional third file that has relocation info, depending on the configuration of **CONFIG_X86_NEED_RELOCS**.

|

||||

|

||||

A host program called **build** , provided by the kernel, builds these two (or three) parts into the final bzImage file.

|

||||

|

||||

#### Dependency tracking

|

||||

|

||||

Kbuild tracks three kinds of dependencies:

|

||||

|

||||

1. All prerequisite files (both * **.c** and * **.h** )

|

||||

2. **CONFIG_** options used in all prerequisite files

|

||||

3. Command-line dependencies used to compile the target

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The first one is easy to understand, but what about the second and third? Kernel developers often see code pieces like this:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

#ifdef CONFIG_SMP

|

||||

__boot_cpu_id = cpu;

|

||||

#endif

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

When **CONFIG_SMP** changes, this piece of code should be recompiled. The command line for compiling a source file also matters, because different command lines may result in different object files.

|

||||

|

||||

When a **.c** file uses a header file via a **#include** directive, you need write a rule like this:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

main.o: defs.h

|

||||

recipe...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

When managing a large project, you need a lot of these kinds of rules; writing them all would be tedious and boring. Fortunately, most modern C compilers can write these rules for you by looking at the **#include** lines in the source file. For the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC), it is just a matter of adding a command-line parameter: **-MD depfile**

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

# In scripts/Makefile.lib

|

||||

c_flags = -Wp,-MD,$(depfile) $(NOSTDINC_FLAGS) $(LINUXINCLUDE) \

|

||||

-include $(srctree)/include/linux/compiler_types.h \

|

||||

$(__c_flags) $(modkern_cflags) \

|

||||

$(basename_flags) $(modname_flags)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This would generate a **.d** file with content like:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

init_task.o: init/init_task.c include/linux/kconfig.h \

|

||||

include/generated/autoconf.h include/linux/init_task.h \

|

||||

include/linux/rcupdate.h include/linux/types.h \

|

||||

...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Then the host program **[fixdep][6]** takes care of the other two dependencies by taking the **depfile** and command line as input, then outputting a **. <target>.cmd** file in makefile syntax, which records the command line and all the prerequisites (including the configuration) for a target. It looks like this:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

# The command line used to compile the target

|

||||

cmd_init/init_task.o := gcc -Wp,-MD,init/.init_task.o.d -nostdinc ...

|

||||

...

|

||||

# The dependency files

|

||||

deps_init/init_task.o := \

|

||||

$(wildcard include/config/posix/timers.h) \

|

||||

$(wildcard include/config/arch/task/struct/on/stack.h) \

|

||||

$(wildcard include/config/thread/info/in/task.h) \

|

||||

...

|

||||

include/uapi/linux/types.h \

|

||||

arch/x86/include/uapi/asm/types.h \

|

||||

include/uapi/asm-generic/types.h \

|

||||

...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

A **. <target>.cmd** file will be included during recursive make, providing all the dependency info and helping to decide whether to rebuild a target or not.

|

||||

|

||||

The secret behind this is that **fixdep** will parse the **depfile** ( **.d** file), then parse all the dependency files inside, search the text for all the **CONFIG_** strings, convert them to the corresponding empty header file, and add them to the target's prerequisites. Every time the configuration changes, the corresponding empty header file will be updated, too, so kbuild can detect that change and rebuild the target that depends on it. Because the command line is also recorded, it is easy to compare the last and current compiling parameters.

|

||||

|

||||

### Looking ahead

|

||||

|

||||

Kconfig/kbuild remained the same for a long time until the new maintainer, Masahiro Yamada, joined in early 2017, and now kbuild is under active development again. Don't be surprised if you soon see something different from what's in this article.

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://opensource.com/article/18/10/kbuild-and-kconfig

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Cao Jin][a]

|

||||

选题:[lujun9972][b]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]: https://opensource.com/users/pinocchio

|

||||

[b]: https://github.com/lujun9972

|

||||

[1]: https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/master/Documentation/kbuild/kconfig-language.txt

|

||||

[2]: https://www.mjmwired.net/kernel/Documentation/kbuild/makefiles.txt

|

||||

[3]: https://opensource.com/file/411516

|

||||

[4]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/vmlinux_generation_process.png (vmlinux overview)

|

||||

[5]: https://blog.csdn.net/richardysteven/article/details/52502734

|

||||

[6]: https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/master/scripts/basic/fixdep.c

|

||||

@ -0,0 +1,258 @@

|

||||

探索 Linux 内核:Kconfig/kbuild 的秘密

|

||||

======

|

||||

|

||||

> 深入理解 Linux 配置/构建系统是如何工作的。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

自从 Linux 内核代码迁移到 Git 以来,Linux 内核配置/构建系统(也称为 Kconfig/kbuild)已存在很长时间了。然而,作为支持基础设施,它很少成为人们关注的焦点;甚至在日常工作中使用它的内核开发人员也从未真正思考过它。

|

||||

|

||||

为了探索如何编译 Linux 内核,本文将深入介绍 Kconfig/kbuild 内部的过程,解释如何生成 `.config` 文件和 `vmlinux`/`bzImage` 文件,并介绍依赖性跟踪的巧妙的技巧。

|

||||

|

||||

### Kconfig

|

||||

|

||||

构建内核的第一步始终是配置。Kconfig 有助于使 Linux 内核高度模块化和可定制。Kconfig 为用户提供了许多配置目标:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

| 配置目标 | 解释 |

|

||||

| ---------------- | --------------------------------------------------------- |

|

||||

| `config` | 利用命令行程序更新当前配置 |

|

||||

| `nconfig` | 利用基于 ncurses 菜单的程序更新当前配置 |

|

||||

| `menuconfig` | 利用基于菜单的程序更新当前配置 |

|

||||

| `xconfig` | 利用基于 Qt 的前端程序更新当前配置 |

|

||||

| `gconfig` | 利用基于 GTK+ 的前端程序更新当前配置 |

|

||||

| `oldconfig` | 基于提供的 `.config` 更新当前配置 |

|

||||

| `localmodconfig` | 更新当前配置,禁用没有载入的模块 |

|

||||

| `localyesconfig` | 更新当前配置,转换本地模块到核心 |

|

||||

| `defconfig` | 带有来自架构提供的 `defconcig` 默认值的新配置 |

|

||||

| `savedefconfig` | 保存当前配置为 `./defconfig`(极简配置) |

|

||||

| `allnoconfig` | 所有选项回答为 `no` 的新配置 |

|

||||

| `allyesconfig` | 所有选项回答为 `yes` 的新配置 |

|

||||

| `allmodconfig` | 尽可能选择所有模块的新配置 |

|

||||

| `alldefconfig` | 所有符号设置为默认值的新配置 |

|

||||

| `randconfig` | 所有选项随机选择的新配置 |

|

||||

| `listnewconfig` | 列出新选项 |

|

||||

| `olddefconfig` | 同 `oldconfig` 一样,但设置新符号为其默认值而无须提问 |

|

||||

| `kvmconfig` | 启用支持 KVM 访客模块的附加选项 |

|

||||

| `xenconfig` | 启用支持 xen 的 dom0 和 访客模块的附加选项 |

|

||||

| `tinyconfig` | 配置尽可能小的内核 |

|

||||

|

||||

我认为 `menuconfig` 是这些目标中最受欢迎的。这些目标由不同的主程序处理,这些程序由内核提供并在内核构建期间构建。一些目标有 GUI(为了方便用户),而大多数没有。与 Kconfig 相关的工具和源代码主要位于内核源代码中的 `scripts/kconfig/` 下。从 `scripts/kconfig/Makefile` 中可以看到,这里有几个主程序,包括 `conf`、`mconf` 和 `nconf`。除了 `conf` 之外,每个都负责一个基于 GUI 的配置目标,因此,`conf` 处理大多数。

|

||||

|

||||

从逻辑上讲,Kconfig 的基础结构有两部分:一部分实现一种[新语言][1]来定义配置项(参见内核源代码下的 Kconfig 文件),另一部分解析 Kconfig 语言并处理配置操作。

|

||||

|

||||

大多数配置目标具有大致相同的内部过程(如下所示):

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

请注意,所有配置项都具有默认值。

|

||||

|

||||

第一步读取源根目录下的 Kconfig 文件,构建初始配置数据库;然后它根据此优先级读取现有配置文件来更新初始数据库:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

.config

|

||||

/lib/modules/$(shell,uname -r)/.config

|

||||

/etc/kernel-config

|

||||

/boot/config-$(shell,uname -r)

|

||||

ARCH_DEFCONFIG

|

||||

arch/$(ARCH)/defconfig

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

如果你通过 `menuconfig` 进行基于 GUI 的配置或通过 `oldconfig` 进行基于命令行的配置,则根据你的自定义更新数据库。最后,配置数据库被转储到 `.config` 文件中。

|

||||

|

||||

但 `.config` 文件不是内核构建的最终素材;这就是 `syncconfig` 目标存在的原因。`syncconfig`曾经是一个名为 `silentoldconfig` 的配置目标,但它没有做到其旧名称所说的工作,所以它被重命名。此外,因为它是供内部使用(不适用于用户),所以它已从上述列表中删除。

|

||||

|

||||

以下是 `syncconfig` 的作用:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

`syncconfig` 将 `.config` 作为输入并输出许多其他文件,这些文件分为三类:

|

||||

|

||||

* `auto.conf` & `tristate.conf` 用于 makefile 文本处理。例如,你可以在组件的 makefile 中看到这样的语句:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

obj-$(CONFIG_GENERIC_CALIBRATE_DELAY) += calibrate.o

|

||||

```

|

||||

* `autoconf.h` 用于 C 语言的源文件。

|

||||

* `include/config/` 下空的头文件用于 kbuild 期间的配置依赖性跟踪,如下所述。

|

||||

|

||||

配置完成后,我们将知道哪些文件和代码片段未编译。

|

||||

|

||||

### kbuild

|

||||

|

||||

组件式构建,称为*递归 make*,是 GNU `make` 管理大型项目的常用方法。Kbuild 是递归 make 的一个很好的例子。通过将源文件划分为不同的模块/组件,每个组件都由其自己的 makefile 管理。当你开始构建时,顶级 makefile 以正确的顺序调用每个组件的 makefile、构建组件,并将它们收集到最终的执行程序中。

|

||||

|

||||

kbuild 指向到不同类型的 makefile:

|

||||

|

||||

* `Makefile` 位于源代码根目录的顶级 makefile。

|

||||

* `.config` 是内核配置文件。

|

||||

* `arch/$(ARCH)/Makefile` 是架构的 makefile,它用于补充顶级 makefile。

|

||||

* `scripts/Makefile.*` 描述所有的 kbuild makefile 的通用规则。

|

||||

* 最后,大约有 500 个 kbuild makefile。

|

||||

|

||||

顶级 makefile 会包含架构 makefile,读取 `.config` 文件,下到子目录,在 `scripts/ Makefile.*` 中定义的例程的帮助下,在每个组件的 makefile 上调用`make`,构建每个中间对象,并将所有的中间对象链接为 `vmlinux`。内核文档 [Documentation/kbuild/makefiles.txt][2] 描述了这些 makefile 的方方面面。

|

||||

|

||||

作为一个例子,让我们看看如何在 x86-64 上生成 `vmlinux`:

|

||||

|

||||

![vmlinux overview][4]

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

(插图基于 Richard Y. Steven 的[博客][5]。有过更新,并在作者允许的情况下使用。)

|

||||

|

||||

进入 `vmlinux` 的所有 `.o` 文件首先进入它们自己的 `built-in.a`,它通过变量`KBUILD_VMLINUX_INIT`、`KBUILD_VMLINUX_MAIN`、`KBUILD_VMLINUX_LIBS` 表示,然后被收集到 `vmlinux` 文件中。

|

||||

|

||||

在下面这个简化的 makefile 代码的帮助下,了解如何在 Linux 内核中实现递归 make:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

# In top Makefile

|

||||

vmlinux: scripts/link-vmlinux.sh $(vmlinux-deps)

|

||||

+$(call if_changed,link-vmlinux)

|

||||

|

||||

# Variable assignments

|

||||

vmlinux-deps := $(KBUILD_LDS) $(KBUILD_VMLINUX_INIT) $(KBUILD_VMLINUX_MAIN) $(KBUILD_VMLINUX_LIBS)

|

||||

|

||||

export KBUILD_VMLINUX_INIT := $(head-y) $(init-y)

|

||||

export KBUILD_VMLINUX_MAIN := $(core-y) $(libs-y2) $(drivers-y) $(net-y) $(virt-y)

|

||||

export KBUILD_VMLINUX_LIBS := $(libs-y1)

|

||||

export KBUILD_LDS := arch/$(SRCARCH)/kernel/vmlinux.lds

|

||||

|

||||

init-y := init/

|

||||

drivers-y := drivers/ sound/ firmware/

|

||||

net-y := net/

|

||||

libs-y := lib/

|

||||

core-y := usr/

|

||||

virt-y := virt/

|

||||

|

||||

# Transform to corresponding built-in.a

|

||||

init-y := $(patsubst %/, %/built-in.a, $(init-y))

|

||||

core-y := $(patsubst %/, %/built-in.a, $(core-y))

|

||||

drivers-y := $(patsubst %/, %/built-in.a, $(drivers-y))

|

||||

net-y := $(patsubst %/, %/built-in.a, $(net-y))

|

||||

libs-y1 := $(patsubst %/, %/lib.a, $(libs-y))

|

||||

libs-y2 := $(patsubst %/, %/built-in.a, $(filter-out %.a, $(libs-y)))

|

||||

virt-y := $(patsubst %/, %/built-in.a, $(virt-y))

|

||||

|

||||

# Setup the dependency. vmlinux-deps are all intermediate objects, vmlinux-dirs

|

||||

# are phony targets, so every time comes to this rule, the recipe of vmlinux-dirs

|

||||

# will be executed. Refer "4.6 Phony Targets" of `info make`

|

||||

$(sort $(vmlinux-deps)): $(vmlinux-dirs) ;

|

||||

|

||||

# Variable vmlinux-dirs is the directory part of each built-in.a

|

||||

vmlinux-dirs := $(patsubst %/,%,$(filter %/, $(init-y) $(init-m) \

|

||||

$(core-y) $(core-m) $(drivers-y) $(drivers-m) \

|

||||

$(net-y) $(net-m) $(libs-y) $(libs-m) $(virt-y)))

|

||||

|

||||

# The entry of recursive make

|

||||

$(vmlinux-dirs):

|

||||

$(Q)$(MAKE) $(build)=$@ need-builtin=1

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

递归 make 的<ruby>配方<rt>recipe</rt></ruby>被扩展开是这样的:

|

||||

|

||||

The recursive make recipe is expanded, for example:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

make -f scripts/Makefile.build obj=init need-builtin=1

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

这意味着 `make` 将进入 `scripts/Makefile.build` 以继续构建每个 `built-in.a` 的工作。在`scripts/link-vmlinux.sh` 的帮助下,`vmlinux` 文件最终位于源根目录下。

|

||||

|

||||

#### vmlinux 与 bzImage 对比

|

||||

|

||||

许多 Linux 内核开发人员可能不清楚 `vmlinux` 和 `bzImage` 之间的关系。例如,这是他们在 x86-64 中的关系:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

源代码根目录下的 `vmlinux` 被剥离、压缩后,放入 `piggy.S`,然后与其他对等对象链接到 `arch/x86/boot/compressed/vmlinux`。同时,在 `arch/x86/boot` 下生成一个名为 `setup.bin` 的文件。可能有一个可选的第三个文件,它具有重定位信息,具体取决于 `CONFIG_X86_NEED_RELOCS` 的配置。

|

||||

|

||||

由内核提供的称为 `build` 的宿主程序将这两个(或三个)部分构建到最终的 `bzImage` 文件中。

|

||||

|

||||

#### 依赖跟踪

|

||||

|

||||

kbuild 跟踪三种依赖关系:

|

||||

|

||||

1. 所有必备文件(`*.c` 和 `*.h`)

|

||||

2. 所有必备文件中使用的 `CONFIG_` 选项

|

||||

3. 用于编译该目标的命令行依赖项

|

||||

|

||||

第一个很容易理解,但第二个和第三个呢? 内核开发人员经常会看到如下代码:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

#ifdef CONFIG_SMP

|

||||

__boot_cpu_id = cpu;

|

||||

#endif

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

当 `CONFIG_SMP` 改变时,这段代码应该重新编译。编译源文件的命令行也很重要,因为不同的命令行可能会导致不同的目标文件。

|

||||

|

||||

当 `.c` 文件通过 `#include` 指令使用头文件时,你需要编写如下规则:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

main.o: defs.h

|

||||

recipe...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

管理大型项目时,需要大量的这些规则;把它们全部写下来会很乏味无聊。幸运的是,大多数现代 C 编译器都可以通过查看源文件中的 `#include` 行来为你编写这些规则。对于 GNU 编译器集合(GCC),只需添加一个命令行参数:`-MD depfile`

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

# In scripts/Makefile.lib

|

||||

c_flags = -Wp,-MD,$(depfile) $(NOSTDINC_FLAGS) $(LINUXINCLUDE) \

|

||||

-include $(srctree)/include/linux/compiler_types.h \

|

||||

$(__c_flags) $(modkern_cflags) \

|

||||

$(basename_flags) $(modname_flags)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

这将生成一个 `.d` 文件,内容如下:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

init_task.o: init/init_task.c include/linux/kconfig.h \

|

||||

include/generated/autoconf.h include/linux/init_task.h \

|

||||

include/linux/rcupdate.h include/linux/types.h \

|

||||

...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

然后主程序 [fixdep][6] 通过将 depfile 和命令行作为输入来处理其他两个依赖项,然后以 makefile 格式输出一个 `.<target>.cmd` 文件,它记录命令行和目标的所有先决条件(包括配置)。 它看起来像这样:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

# The command line used to compile the target

|

||||

cmd_init/init_task.o := gcc -Wp,-MD,init/.init_task.o.d -nostdinc ...

|

||||

...

|

||||

# The dependency files

|

||||

deps_init/init_task.o := \

|

||||

$(wildcard include/config/posix/timers.h) \

|

||||

$(wildcard include/config/arch/task/struct/on/stack.h) \

|

||||

$(wildcard include/config/thread/info/in/task.h) \

|

||||

...

|

||||

include/uapi/linux/types.h \

|

||||

arch/x86/include/uapi/asm/types.h \

|

||||

include/uapi/asm-generic/types.h \

|

||||

...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

在递归 make 中,`.<target>.cmd` 文件将被包括,以提供所有依赖关系信息并帮助决定是否重建目标。

|

||||

|

||||

这背后的秘密是 `fixdep` 将解析 depfile(`.d` 文件),然后解析里面的所有依赖文件,搜索所有 `CONFIG_` 字符串的文本,将它们转换为相应的空的头文件,并将它们添加到目标的先决条件。每次配置更改时,相应的空的头文件也将更新,因此 kbuild 可以检测到该更改并重建依赖于它的目标。因为还记录了命令行,所以很容易比较最后和当前的编译参数。

|

||||

|

||||

### 展望未来

|

||||

|

||||

Kconfig/kbuild 在很长一段时间内没有什么变化,直到新的维护者 Masahiro Yamada 于 2017 年初加入,现在 kbuild 再次正在积极开发中。如果你不久后看到与本文中的内容不同的内容,请不要感到惊讶。

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://opensource.com/article/18/10/kbuild-and-kconfig

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Cao Jin][a]

|

||||

选题:[lujun9972][b]

|

||||

译者:[wxy](https://github.com/wxy)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]: https://opensource.com/users/pinocchio

|

||||

[b]: https://github.com/lujun9972

|

||||

[1]: https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/master/Documentation/kbuild/kconfig-language.txt

|

||||

[2]: https://www.mjmwired.net/kernel/Documentation/kbuild/makefiles.txt

|

||||

[3]: https://opensource.com/file/411516

|

||||

[4]: https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/uploads/vmlinux_generation_process.png (vmlinux overview)

|

||||

[5]: https://blog.csdn.net/richardysteven/article/details/52502734

|

||||

[6]: https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/master/scripts/basic/fixdep.c

|

||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user