diff --git a/sources/tech/20141028 When Does Your OS Run.md b/sources/tech/20141028 When Does Your OS Run.md

deleted file mode 100644

index 0545ab579d..0000000000

--- a/sources/tech/20141028 When Does Your OS Run.md

+++ /dev/null

@@ -1,55 +0,0 @@

-Translating by Cwndmiao

-

-When Does Your OS Run?

-============================================================

-

-

-Here’s a question: in the time it takes you to read this sentence, has your OS been _running_ ? Or was it only your browser? Or were they perhaps both idle, just waiting for you to _do something already_ ?

-

-These questions are simple but they cut through the essence of how software works. To answer them accurately we need a good mental model of OS behavior, which in turn informs performance, security, and troubleshooting decisions. We’ll build such a model in this post series using Linux as the primary OS, with guest appearances by OS X and Windows. I’ll link to the Linux kernel sources for those who want to delve deeper.

-

-The fundamental axiom here is that _at any given moment, exactly one task is active on a CPU_ . The task is normally a program, like your browser or music player, or it could be an operating system thread, but it is one task. Not two or more. Never zero, either. One. Always.

-

-This sounds like trouble. For what if, say, your music player hogs the CPU and doesn’t let any other tasks run? You would not be able to open a tool to kill it, and even mouse clicks would be futile as the OS wouldn’t process them. You could be stuck blaring “What does the fox say?” and incite a workplace riot.

-

-That’s where interrupts come in. Much as the nervous system interrupts the brain to bring in external stimuli – a loud noise, a touch on the shoulder – the [chipset][1] in a computer’s motherboard interrupts the CPU to deliver news of outside events – key presses, the arrival of network packets, the completion of a hard drive read, and so on. Hardware peripherals, the interrupt controller on the motherboard, and the CPU itself all work together to implement these interruptions, called interrupts for short.

-

-Interrupts are also essential in tracking that which we hold dearest: time. During the [boot process][2] the kernel programs a hardware timer to issue timer interrupts at a periodic interval, for example every 10 milliseconds. When the timer goes off, the kernel gets a shot at the CPU to update system statistics and take stock of things: has the current program been running for too long? Has a TCP timeout expired? Interrupts give the kernel a chance to both ponder these questions and take appropriate actions. It’s as if you set periodic alarms throughout the day and used them as checkpoints: should I be doing what I’m doing right now? Is there anything more pressing? One day you find ten years have got behind you.

-

-These periodic hijackings of the CPU by the kernel are called ticks, so interrupts quite literally make your OS tick. But there’s more: interrupts are also used to handle some software events like integer overflows and page faults, which involve no external hardware. Interrupts are the most frequent and crucial entry point into the OS kernel. They’re not some oddity for the EE people to worry about, they’re _the_ mechanism whereby your OS runs.

-

-Enough talk, let’s see some action. Below is a network card interrupt in an Intel Core i5 system. The diagrams now have image maps, so you can click on juicy bits for more information. For example, each device links to its Linux driver.

-

-

-

-

-

-Let’s take a look at this. First off, since there are many sources of interrupts, it wouldn’t be very helpful if the hardware simply told the CPU “hey, something happened!” and left it at that. The suspense would be unbearable. So each device is assigned an interrupt request line, or IRQ, during power up. These IRQs are in turn mapped into interrupt vectors, a number between 0 and 255, by the interrupt controller. By the time an interrupt reaches the CPU it has a nice, well-defined number insulated from the vagaries of hardware.

-

-The CPU in turn has a pointer to what’s essentially an array of 255 functions, supplied by the kernel, where each function is the handler for that particular interrupt vector. We’ll look at this array, the Interrupt Descriptor Table (IDT), in more detail later on.

-

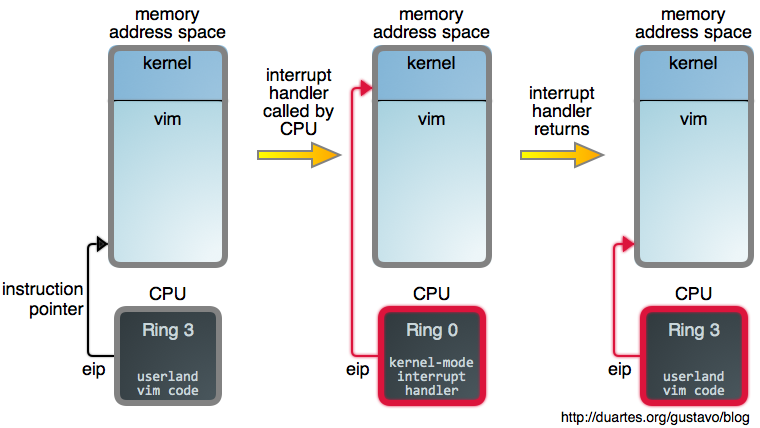

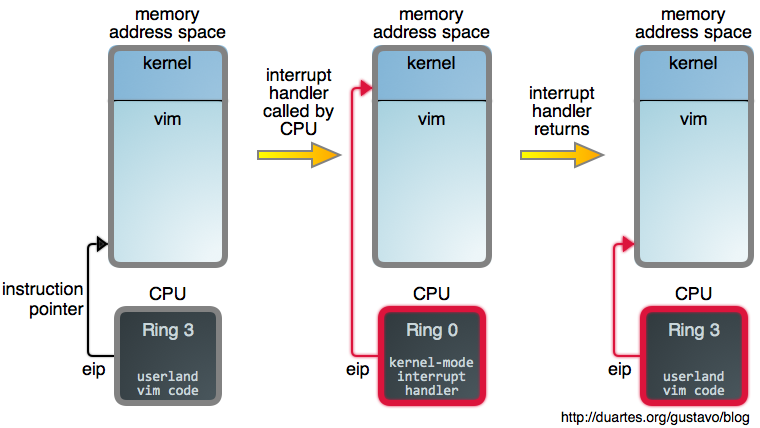

-Whenever an interrupt arrives, the CPU uses its vector as an index into the IDT and runs the appropriate handler. This happens as a special function call that takes place in the context of the currently running task, allowing the OS to respond to external events quickly and with minimal overhead. So web servers out there indirectly _call a function in your CPU_ when they send you data, which is either pretty cool or terrifying. Below we show a situation where a CPU is busy running a Vim command when an interrupt arrives:

-

-

-

-Notice how the interrupt’s arrival causes a switch to kernel mode and [ring zero][3] but it _does not change the active task_ . It’s as if Vim made a magic function call straight into the kernel, but Vim is _still there_ , its [address space][4] intact, waiting for that call to return.

-

-Exciting stuff! Alas, I need to keep this post-sized, so let’s finish up for now. I understand we have not answered the opening question and have in fact opened up new questions, but you now suspect ticks were taking place while you read that sentence. We’ll find the answers as we flesh out our model of dynamic OS behavior, and the browser scenario will become clear. If you have questions, especially as the posts come out, fire away and I’ll try to answer them in the posts themselves or as comments. Next installment is tomorrow on [RSS][5] and [Twitter][6].

-

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------

-

-via: http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/post/when-does-your-os-run/

-

-作者:[gustavo ][a]

-译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

-校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

-

-本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

-

-[a]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/about/

-[1]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/post/motherboard-chipsets-memory-map

-[2]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/post/kernel-boot-process

-[3]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/post/cpu-rings-privilege-and-protection

-[4]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/post/anatomy-of-a-program-in-memory

-[5]:http://feeds.feedburner.com/GustavoDuarte

-[6]:http://twitter.com/food4hackers

diff --git a/translated/tech/20141028 When Does Your OS Run.md b/translated/tech/20141028 When Does Your OS Run.md

new file mode 100644

index 0000000000..893dd9fb48

--- /dev/null

+++ b/translated/tech/20141028 When Does Your OS Run.md

@@ -0,0 +1,53 @@

+操作系统何时运行?

+============================================================

+

+

+请各位思考以下问题:在你阅读本文的这段时间内,计算机中的操作系统在运行吗?又或者仅仅是 Web 浏览器在运行?又或者他们也许均处于空闲状态,等待着你的指示?

+

+这些问题并不复杂,但他们深入涉及到系统软件工作的本质。为了准确回答这些问题,我们需要透彻理解操作系统的行为模型,包括性能、安全和除错等方面。在该系列文章中,我们将以 Linux 为主举例来帮助你建立操作系统的行为模型,OS X 和 Windows 在必要的时候也会有所涉及。对那些深度探索者,我会在适当的时候给出 Linux 内核源码的链接。

+

+这里有一个基本认知,就是,在任意给定时刻,某个 CPU 上仅有一个任务处于活动状态。大多数情形下这个任务是某个用户程序,例如你的 Web 浏览器或音乐播放器,但他也可能是一个操作系统线程。可以确信的是,他是一个任务,不是两个或更多,也不是零个,对,永远是一个。

+

+这听上去可能会有些问题。比如,你的音乐播放器是否会独占 CPU 而阻止其他任务运行?从而使你不能打开任务管理工具去杀死音乐播放器,甚至让鼠标点击也失效,因为操作系统没有机会去处理这些事件。你可能会奋而喊出,“他究竟在搞什么鬼?”,并引发骚乱。

+

+此时便轮到中断大显身手了。中断就好比,一声巨响或一次拍肩后,神经系统通知大脑去感知外部刺激一般。计算机主板上的芯片组同样会中断 CPU 运行以传递新的外部事件,例如键盘上的某个键被按下、网络数据包的到达、一次硬盘读的完成,等等。硬件外设、主板上的中断控制器和 CPU 本身,他们共同协作实现了中断机制。

+

+中断对于簿记我们最珍视的资源--时间也至关重要。计算机启动过程中,操作系统内核会设置一个硬件计时器以让其产生周期性计时中断,例如每隔 10 毫秒触发一次。每当计时中断到来,内核便会收到通知以更新系统统计信息和盘点如下事项:当前用户程序是否已运行了足够长时间?是否有某个 TCP 定时器超时了?中断给予了内核一个处理这些问题并采取合适措施的机会。这就好像你给自己设置了整天的周期闹铃并把他们用作检查点:我是否应该去做我正在进行的工作?是否存在更紧急的事项?直到你发现 10 年时间已逝去。。。

+

+这些内核对 CPU 周期性的劫持被称为滴答,也就是说,是中断让操作系统经历了滴答的过程。不止如此,中断也被用作处理一些软件事件,如整数溢出和页错误,其中未涉及外部硬件。中断是进入操作系统内核最频繁也是最重要的入口。对于学习电子工程的人而言,这些并无古怪,他们是操作系统赖以运行的机制。

+

+说到这里,让我们再来看一些实际情形。下图示意了 Intel Core i5 系统中的一个网卡中断。图片现在设置了超链,你可以点击他们以获取更为详细的信息,例如每个设备均被链接到了对应的 Linux 驱动源码。

+

+

+

+

+

+让我们来仔细研究下。首先,由于系统中存在众多中断源,如果硬件只是通知 CPU “嘿,这里发生了一些事情”然后什么也不做,则不太行得通。这会带来难以忍受的冗长等待。因此,计算机上电时,每个设备都被授予了一根中断线,或者称为 IRQ。这些 IRQ 然后被系统中的中断控制器映射成值介于 0 到 255 之间的中断向量。等到中断到达 CPU,他便具备了一个定义良好的数值,异于硬件的某些其他诡异行为。

+

+相应地,CPU 中还存有一个由内核维护的指针,指向一个包含 255 个函数指针的数组,其中每个函数被用来处理某个特定的中断向量。后文中,我们将继续深入探讨这个数组,他也被称作中断描述符表(IDT)。

+

+每当中断到来,CPU 会用中断向量的值去索引中断描述符表,并执行相应处理函数。这相当于,在当前正在执行任务的上下文中,发生了一个特殊函数调用,从而允许操作系统以较小开销快速对外部事件作出反应。考虑下述场景,Web 服务器在发送数据时,CPU 却间接调用了操作系统函数,这听上去要么很炫酷要么令人惊恐。下图展示了 Vim 编辑器运行过程中一个中断到来的情形。

+

+

+

+此处请留意,中断的到来是如何触发 CPU 到 Ring 0 内核模式的切换而未有改变当前活跃的任务。这看上去就像,Vim 编辑器直接面向操作系统内核产生了一次神奇的函数调用,但 Vim 还在那里,他的地址空间原封未动,等待着执行流返回。

+

+这很令人振奋,不是么?不过让我们暂且告一段落吧,我需要合理控制篇幅。我知道还没有回答完这个开放式问题,甚至还实质上翻开了新的问题,但你至少知道了在你读这个句子的同时滴答正在发生。我们将在充实了对操作系统动态行为模型的理解之后再回来寻求问题的答案,对 Web 浏览器情形的理解也会变得清晰。如果你仍有问题,尤其是在这篇文章公诸于众后,请尽管提出。我将会在文章或后续评论中回答他们。下篇文章将于明天在 RSS 和 Twitter 上发布。

+

+--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

+

+via: http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/post/when-does-your-os-run/

+

+作者:[gustavo ][a]

+译者:[Cwndmiao](https://github.com/Cwndmiao)

+校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

+

+本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

+

+[a]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/about/

+[1]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/post/motherboard-chipsets-memory-map

+[2]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/post/kernel-boot-process

+[3]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/post/cpu-rings-privilege-and-protection

+[4]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/post/anatomy-of-a-program-in-memory

+[5]:http://feeds.feedburner.com/GustavoDuarte

+[6]:http://twitter.com/food4hackers