mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-01-25 23:11:02 +08:00

houbaron translated

This commit is contained in:

parent

1cd1f1c255

commit

792b8112b5

@ -1,495 +0,0 @@

|

||||

Translating By houbaron

|

||||

|

||||

Five things that make Go fast

|

||||

============================================================

|

||||

|

||||

_Anthony Starks has remixed my original Google Present based slides using his fantastic Deck presentation tool. You can check out his remix over on his blog,[mindchunk.blogspot.com.au/2014/06/remixing-with-deck][5]._

|

||||

|

||||

* * *

|

||||

|

||||

I was recently invited to give a talk at Gocon, a fantastic Go conference held semi-annually in Tokyo, Japan. [Gocon 2014][6] was an entirely community-run one day event combining training and an afternoon of presentations surrounding the theme of <q style="border: 0px; vertical-align: baseline; quotes: none;">Go in production</q>.

|

||||

|

||||

The following is the text of my presentation. The original text was structured to force me to speak slowly and clearly, so I have taken the liberty of editing it slightly to be more readable.

|

||||

|

||||

I want to thank [Bill Kennedy][7], Minux Ma, and especially [Josh Bleecher Snyder][8], for their assistance in preparing this talk.

|

||||

|

||||

* * *

|

||||

|

||||

Good afternoon.

|

||||

|

||||

My name is David.

|

||||

|

||||

I am delighted to be here at Gocon today. I have wanted to come to this conference for two years and I am very grateful to the organisers for extending me the opportunity to present to you today.

|

||||

|

||||

[][9]

|

||||

I want to begin my talk with a question.

|

||||

|

||||

Why are people choosing to use Go ?

|

||||

|

||||

When people talk about their decision to learn Go, or use it in their product, they have a variety of answers, but there always three that are at the top of their list

|

||||

|

||||

[][10]

|

||||

These are the top three.

|

||||

|

||||

The first, Concurrency.

|

||||

|

||||

Go’s concurrency primitives are attractive to programmers who come from single threaded scripting languages like Nodejs, Ruby, or Python, or from languages like C++ or Java with their heavyweight threading model.

|

||||

|

||||

Ease of deployment.

|

||||

|

||||

We have heard today from experienced Gophers who appreciate the simplicity of deploying Go applications.

|

||||

|

||||

[][11]

|

||||

|

||||

This leaves Performance.

|

||||

|

||||

I believe an important reason why people choose to use Go is because it is _fast_ .

|

||||

|

||||

[][12]

|

||||

|

||||

For my talk today I want to discuss five features that contribute to Go’s performance.

|

||||

|

||||

I will also share with you the details of how Go implements these features.

|

||||

|

||||

[][13]

|

||||

|

||||

The first feature I want to talk about is Go’s efficient treatment and storage of values.

|

||||

|

||||

[][14]

|

||||

|

||||

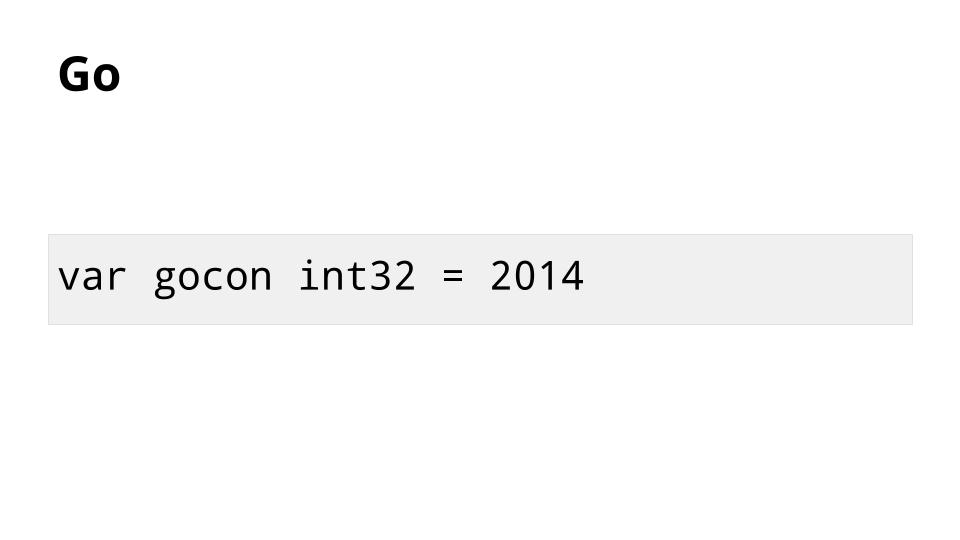

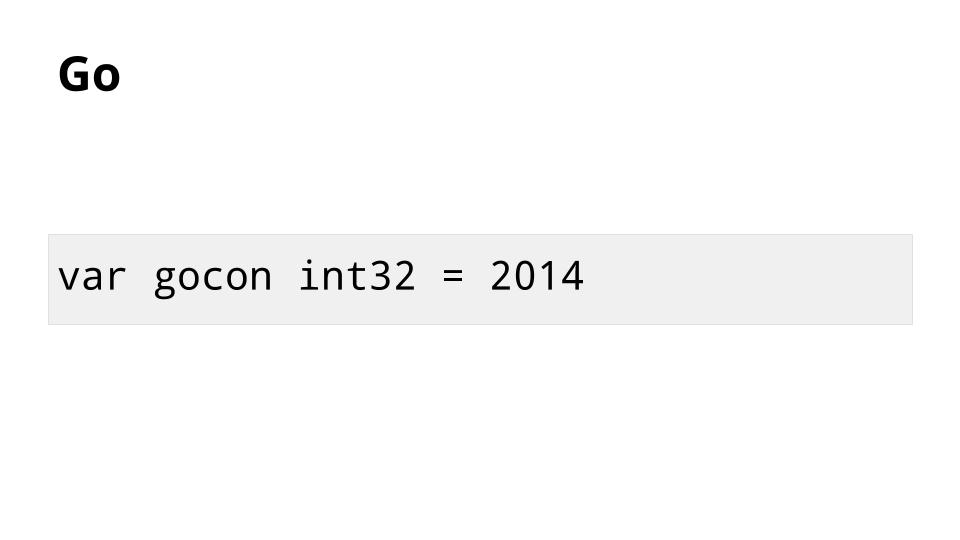

This is an example of a value in Go. When compiled, `gocon` consumes exactly four bytes of memory.

|

||||

|

||||

Let’s compare Go with some other languages

|

||||

|

||||

[][15]

|

||||

|

||||

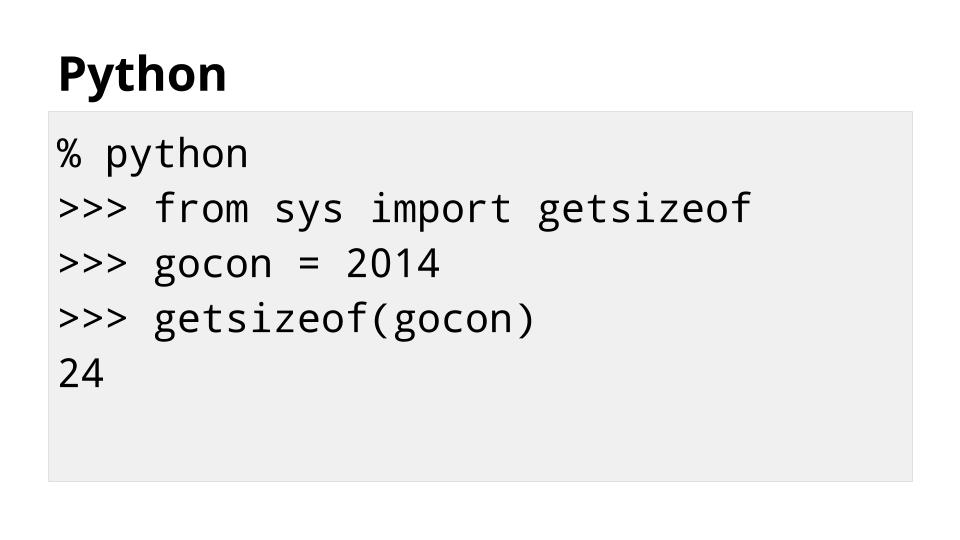

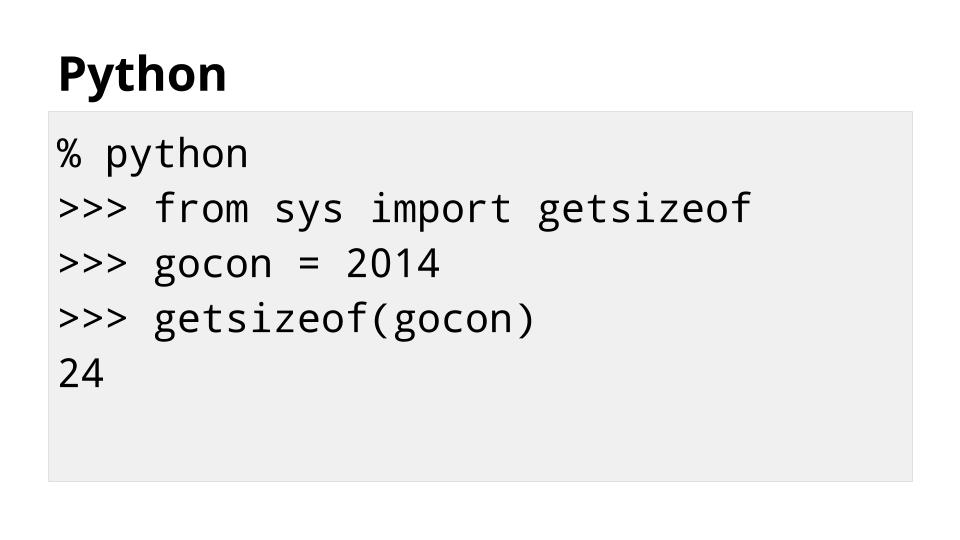

Due to the overhead of the way Python represents variables, storing the same value using Python consumes six times more memory.

|

||||

|

||||

This extra memory is used by Python to track type information, do reference counting, etc

|

||||

|

||||

Let’s look at another example:

|

||||

|

||||

[][16]

|

||||

|

||||

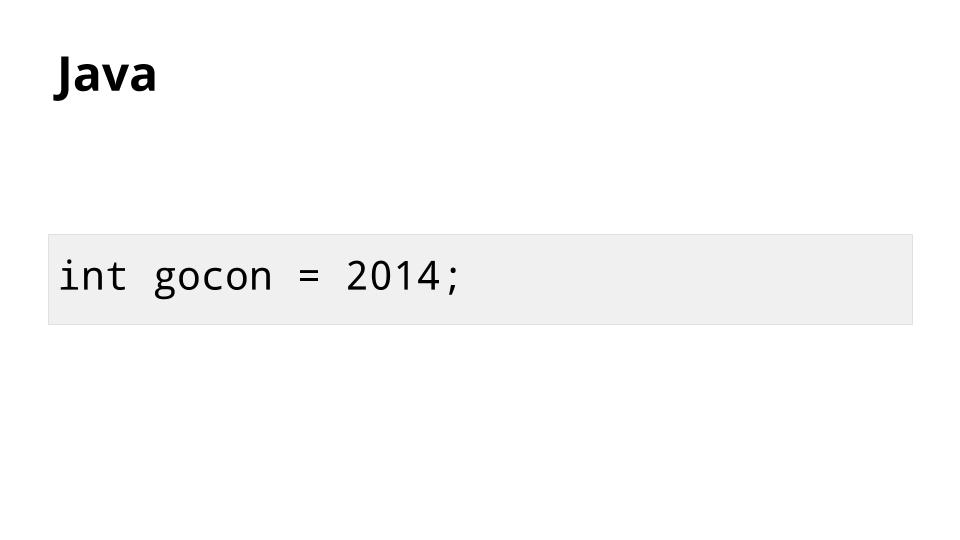

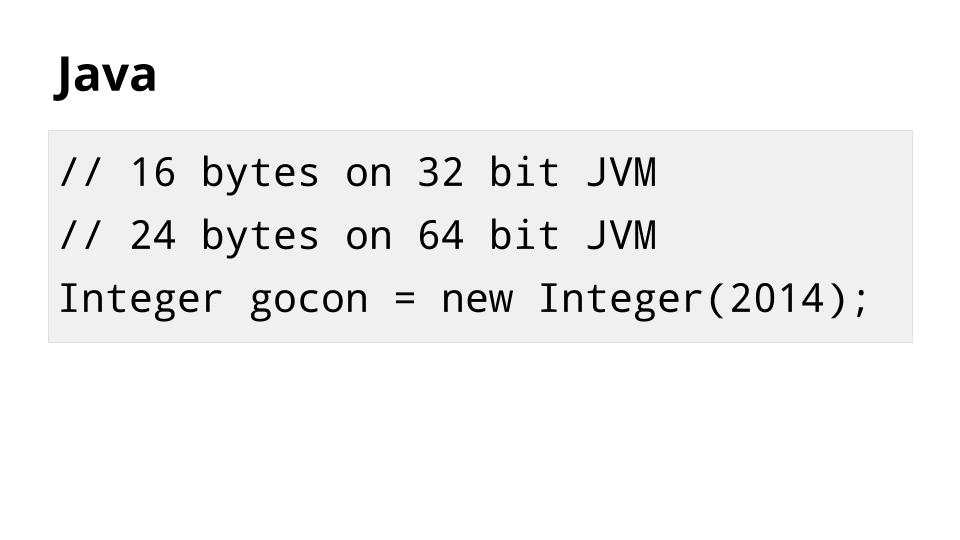

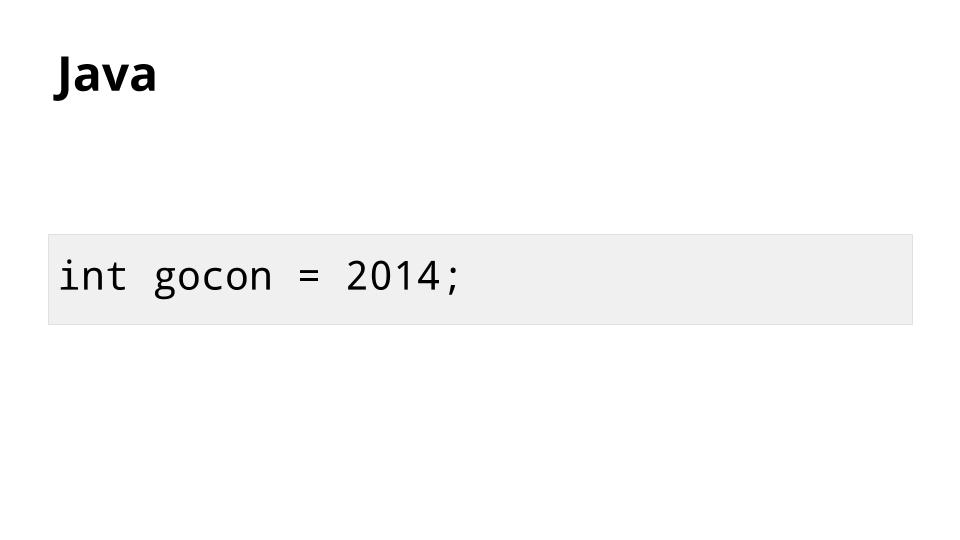

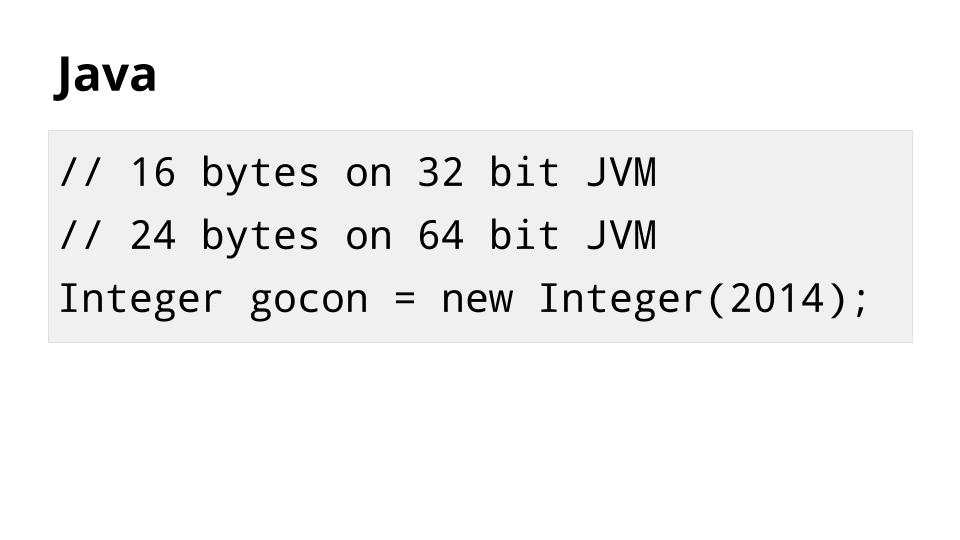

Similar to Go, the Java `int` type consumes 4 bytes of memory to store this value.

|

||||

|

||||

However, to use this value in a collection like a `List` or `Map`, the compiler must convert it into an `Integer` object.

|

||||

|

||||

[][17]

|

||||

|

||||

So an integer in Java frequently looks more like this and consumes between 16 and 24 bytes of memory.

|

||||

|

||||

Why is this important ? Memory is cheap and plentiful, why should this overhead matter ?

|

||||

|

||||

[][18]

|

||||

|

||||

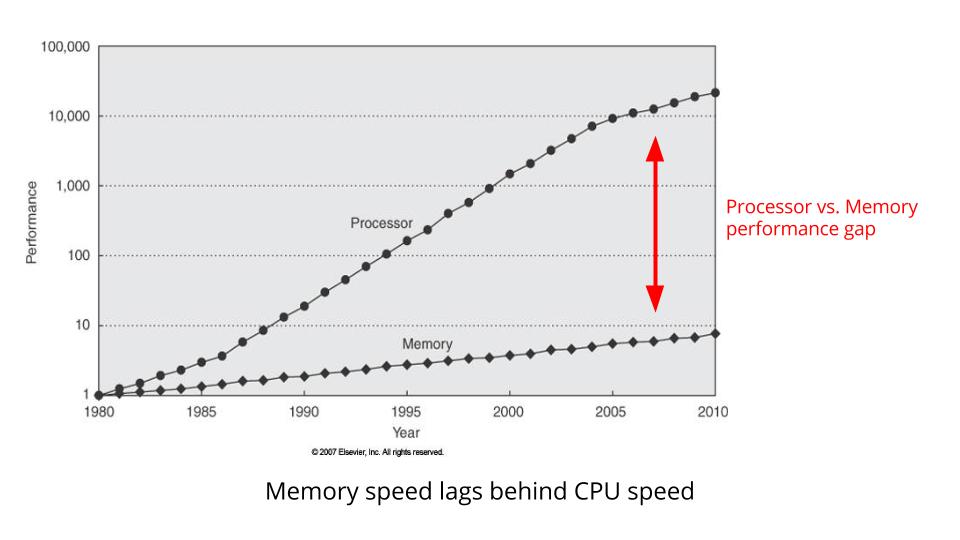

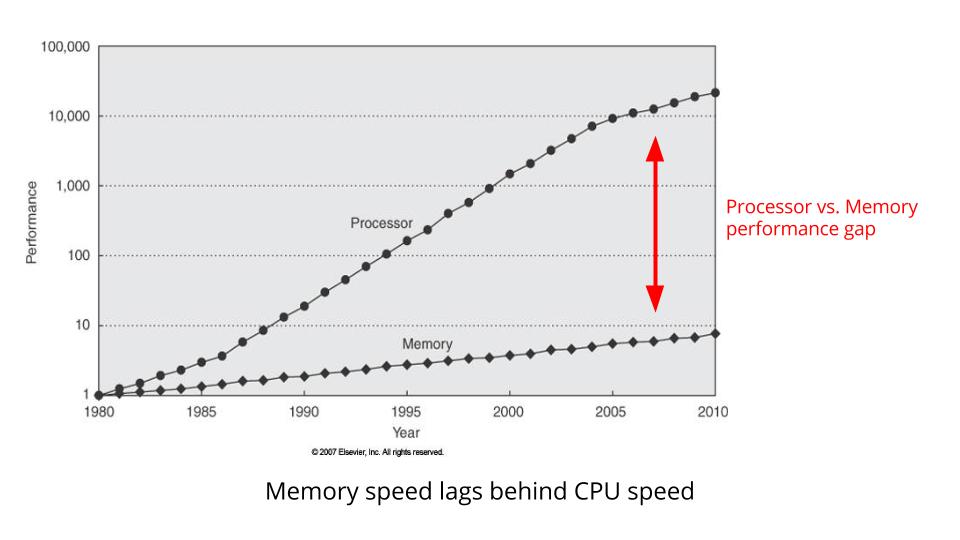

This is a graph showing CPU clock speed vs memory bus speed.

|

||||

|

||||

Notice how the gap between CPU clock speed and memory bus speed continues to widen.

|

||||

|

||||

The difference between the two is effectively how much time the CPU spends waiting for memory.

|

||||

|

||||

[][19]

|

||||

|

||||

Since the late 1960’s CPU designers have understood this problem.

|

||||

|

||||

Their solution is a cache, an area of smaller, faster memory which is inserted between the CPU and main memory.

|

||||

|

||||

[][20]

|

||||

|

||||

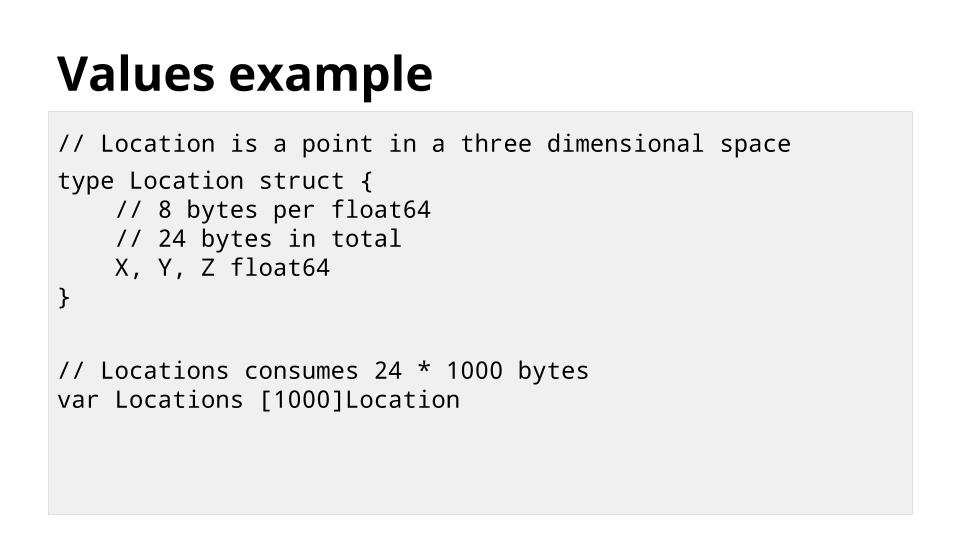

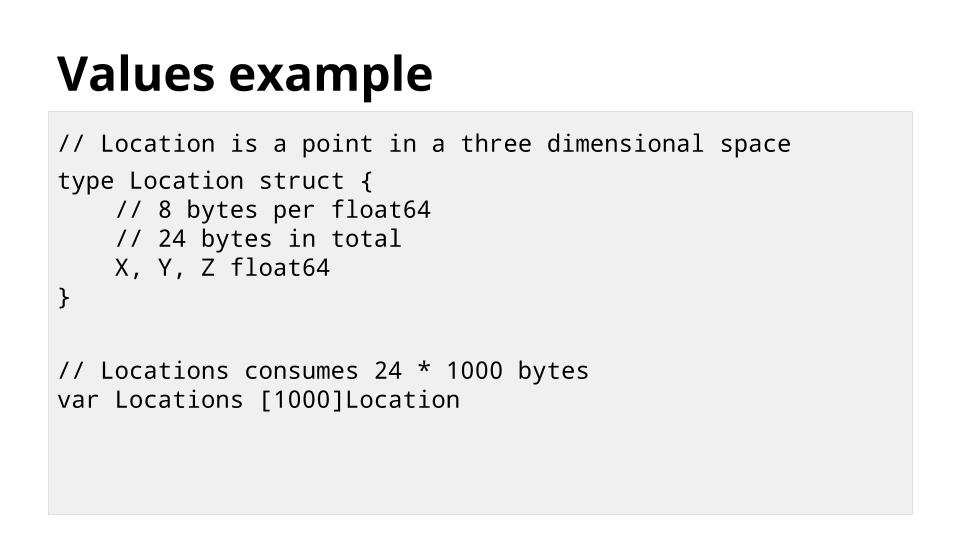

This is a `Location` type which holds the location of some object in three dimensional space. It is written in Go, so each `Location` consumes exactly 24 bytes of storage.

|

||||

|

||||

We can use this type to construct an array type of 1,000 `Location`s, which consumes exactly 24,000 bytes of memory.

|

||||

|

||||

Inside the array, the `Location` structures are stored sequentially, rather than as pointers to 1,000 Location structures stored randomly.

|

||||

|

||||

This is important because now all 1,000 `Location` structures are in the cache in sequence, packed tightly together.

|

||||

|

||||

[][21]

|

||||

|

||||

Go lets you create compact data structures, avoiding unnecessary indirection.

|

||||

|

||||

Compact data structures utilise the cache better.

|

||||

|

||||

Better cache utilisation leads to better performance.

|

||||

|

||||

[][22]

|

||||

|

||||

Function calls are not free.

|

||||

|

||||

[][23]

|

||||

|

||||

Three things happen when a function is called.

|

||||

|

||||

A new stack frame is created, and the details of the caller recorded.

|

||||

|

||||

Any registers which may be overwritten during the function call are saved to the stack.

|

||||

|

||||

The processor computes the address of the function and executes a branch to that new address.

|

||||

|

||||

[][24]

|

||||

|

||||

Because function calls are very common operations, CPU designers have worked hard to optimise this procedure, but they cannot eliminate the overhead.

|

||||

|

||||

Depending on what the function does, this overhead may be trivial or significant.

|

||||

|

||||

A solution to reducing function call overhead is an optimisation technique called Inlining.

|

||||

|

||||

[][25]

|

||||

|

||||

The Go compiler inlines a function by treating the body of the function as if it were part of the caller.

|

||||

|

||||

Inlining has a cost; it increases binary size.

|

||||

|

||||

It only makes sense to inline when the overhead of calling a function is large relative to the work the function does, so only simple functions are candidates for inlining.

|

||||

|

||||

Complicated functions are usually not dominated by the overhead of calling them and are therefore not inlined.

|

||||

|

||||

[][26]

|

||||

|

||||

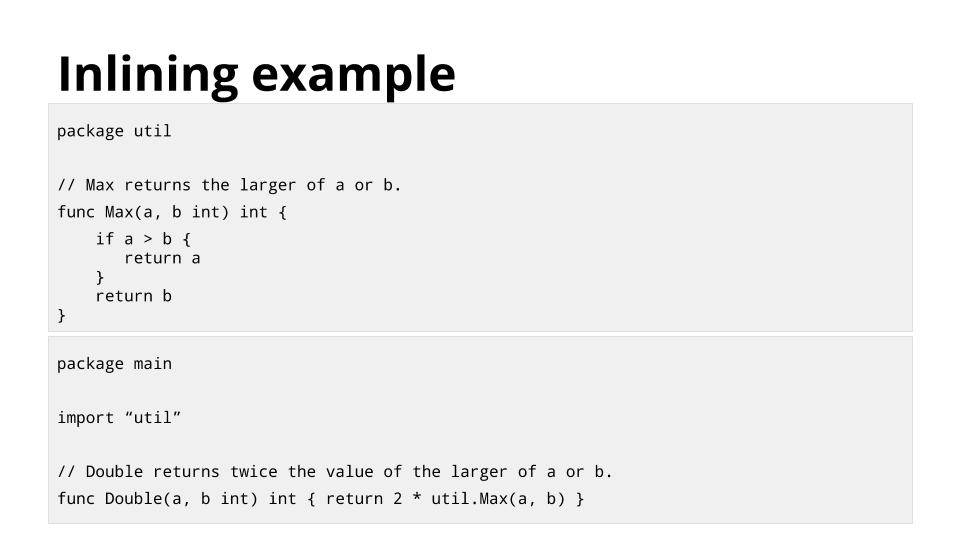

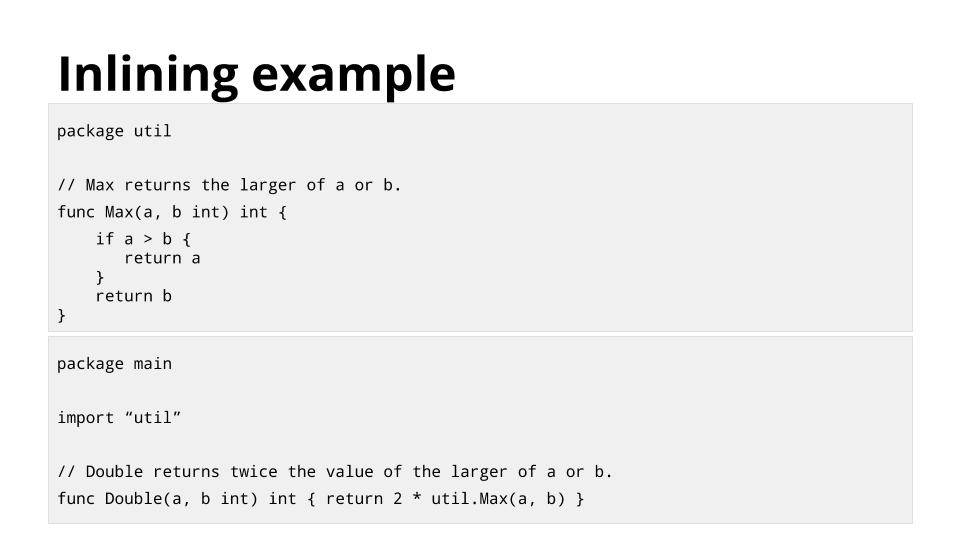

This example shows the function `Double` calling `util.Max`.

|

||||

|

||||

To reduce the overhead of the call to `util.Max`, the compiler can inline `util.Max` into `Double`, resulting in something like this

|

||||

|

||||

[][27]

|

||||

|

||||

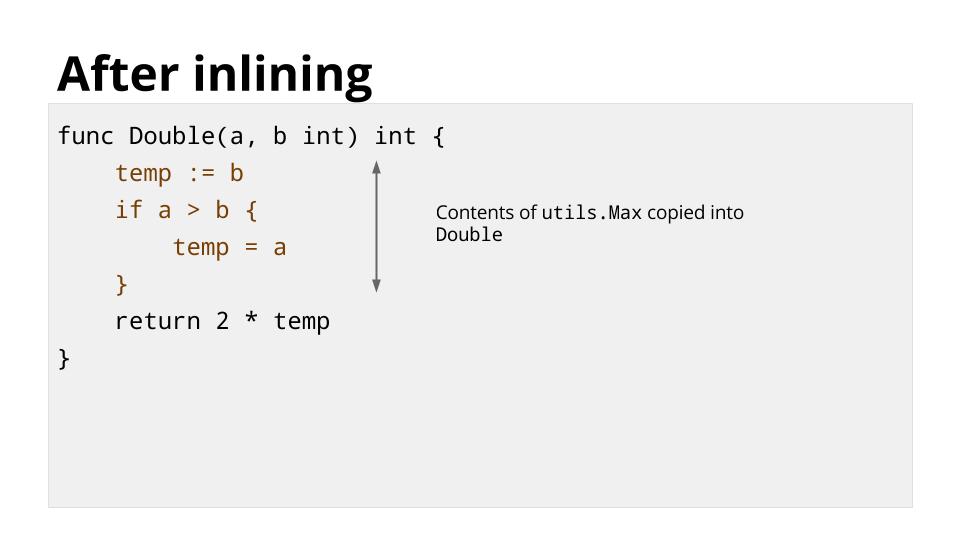

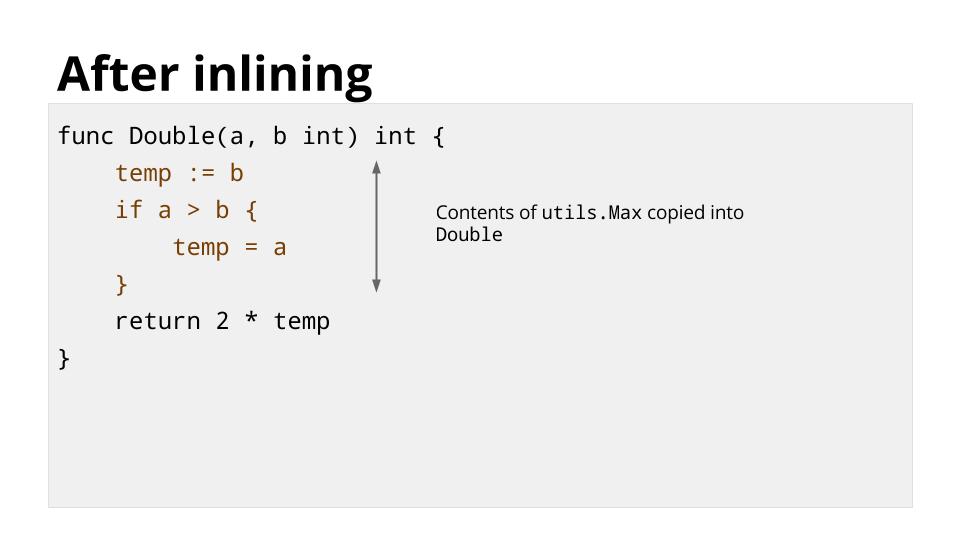

After inlining there is no longer a call to `util.Max`, but the behaviour of `Double` is unchanged.

|

||||

|

||||

Inlining isn’t exclusive to Go. Almost every compiled or JITed language performs this optimisation. But how does inlining in Go work?

|

||||

|

||||

The Go implementation is very simple. When a package is compiled, any small function that is suitable for inlining is marked and then compiled as usual.

|

||||

|

||||

Then both the source of the function and the compiled version are stored.

|

||||

|

||||

[][28]

|

||||

|

||||

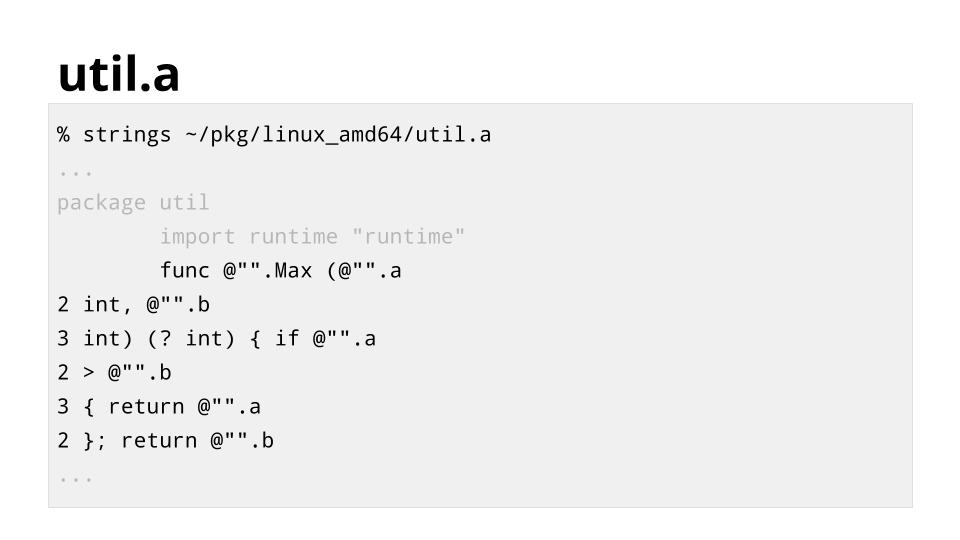

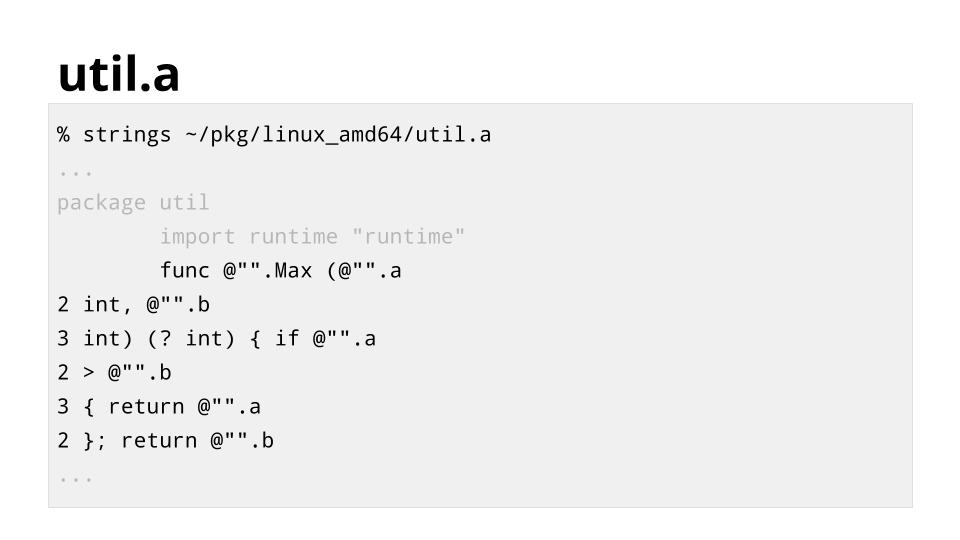

This slide shows the contents of util.a. The source has been transformed a little to make it easier for the compiler to process quickly.

|

||||

|

||||

When the compiler compiles Double it sees that `util.Max` is inlinable, and the source of `util.Max`is available.

|

||||

|

||||

Rather than insert a call to the compiled version of `util.Max`, it can substitute the source of the original function.

|

||||

|

||||

Having the source of the function enables other optimizations.

|

||||

|

||||

[][29]

|

||||

|

||||

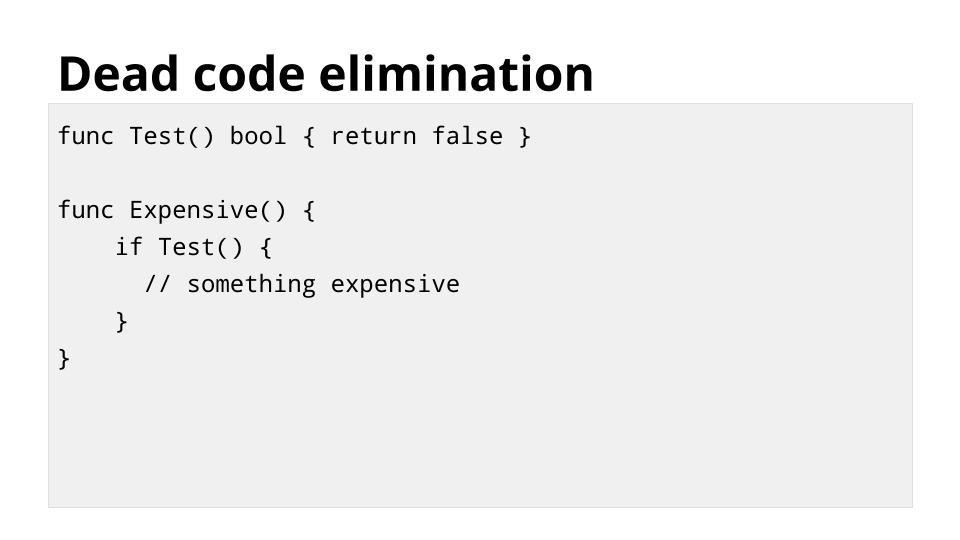

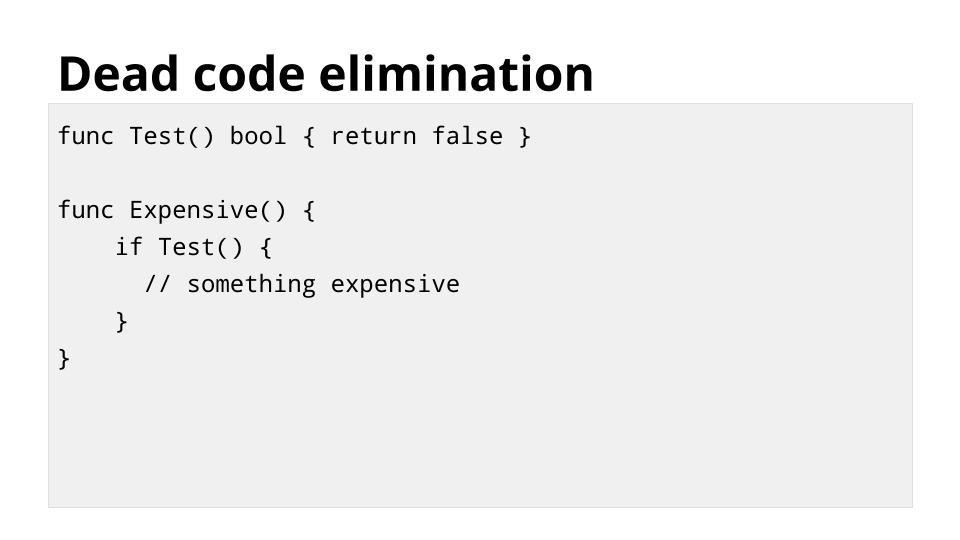

In this example, although the function Test always returns false, Expensive cannot know that without executing it.

|

||||

|

||||

When `Test` is inlined, we get something like this

|

||||

|

||||

[][30]

|

||||

|

||||

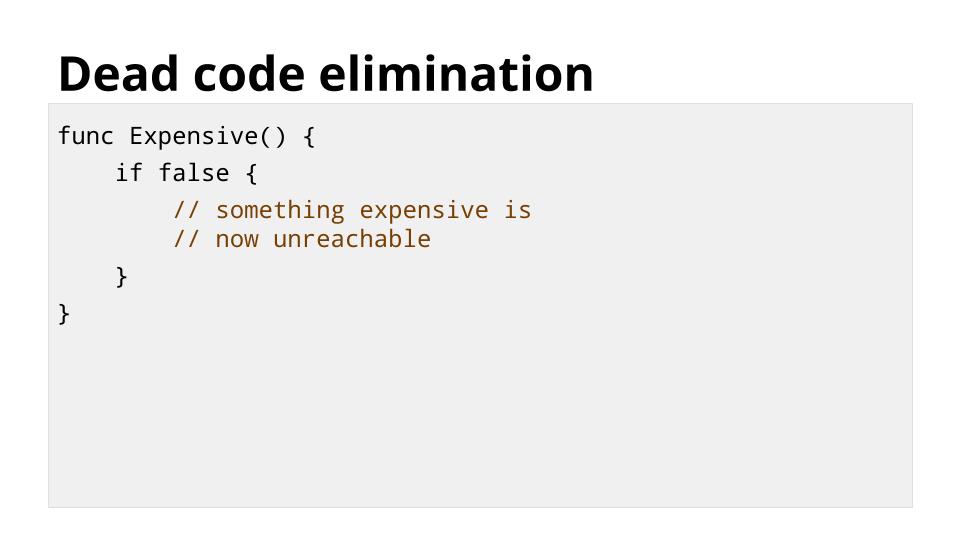

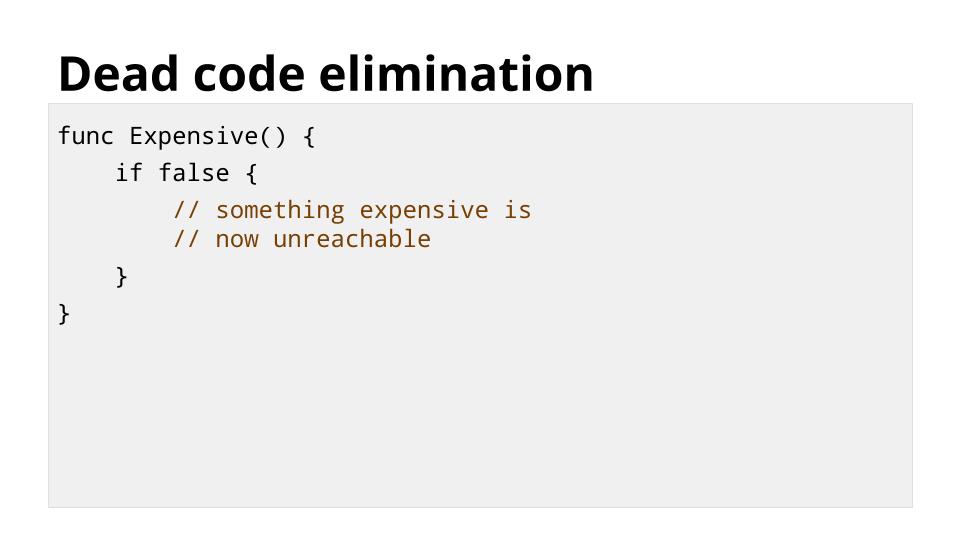

The compiler now knows that the expensive code is unreachable.

|

||||

|

||||

Not only does this save the cost of calling Test, it saves compiling or running any of the expensive code that is now unreachable.

|

||||

|

||||

The Go compiler can automatically inline functions across files and even across packages. This includes code that calls inlinable functions from the standard library.

|

||||

|

||||

[][31]

|

||||

|

||||

Mandatory garbage collection makes Go a simpler and safer language.

|

||||

|

||||

This does not imply that garbage collection makes Go slow, or that garbage collection is the ultimate arbiter of the speed of your program.

|

||||

|

||||

What it does mean is memory allocated on the heap comes at a cost. It is a debt that costs CPU time every time the GC runs until that memory is freed.

|

||||

|

||||

[][32]

|

||||

|

||||

There is however another place to allocate memory, and that is the stack.

|

||||

|

||||

Unlike C, which forces you to choose if a value will be stored on the heap, via `malloc`, or on the stack, by declaring it inside the scope of the function, Go implements an optimisation called _escape analysis_ .

|

||||

|

||||

[][33]

|

||||

|

||||

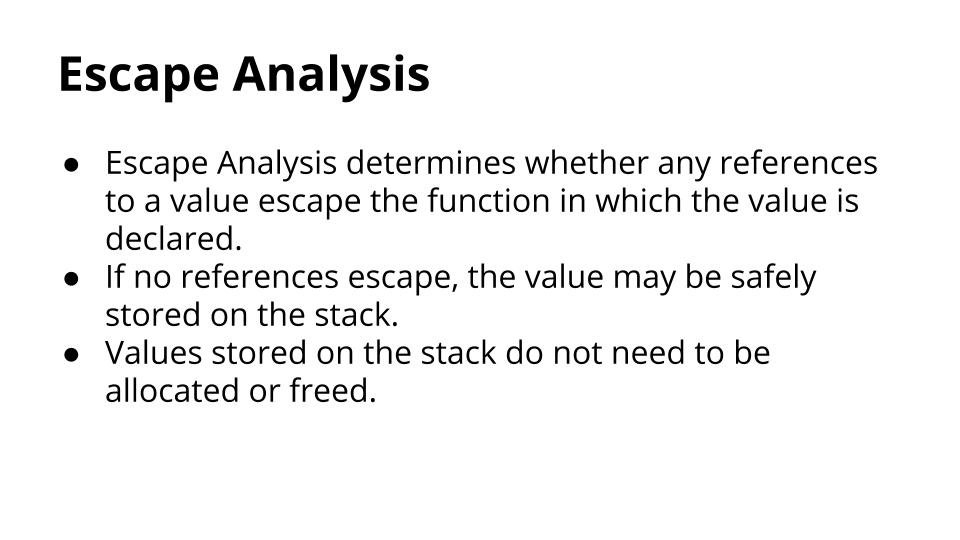

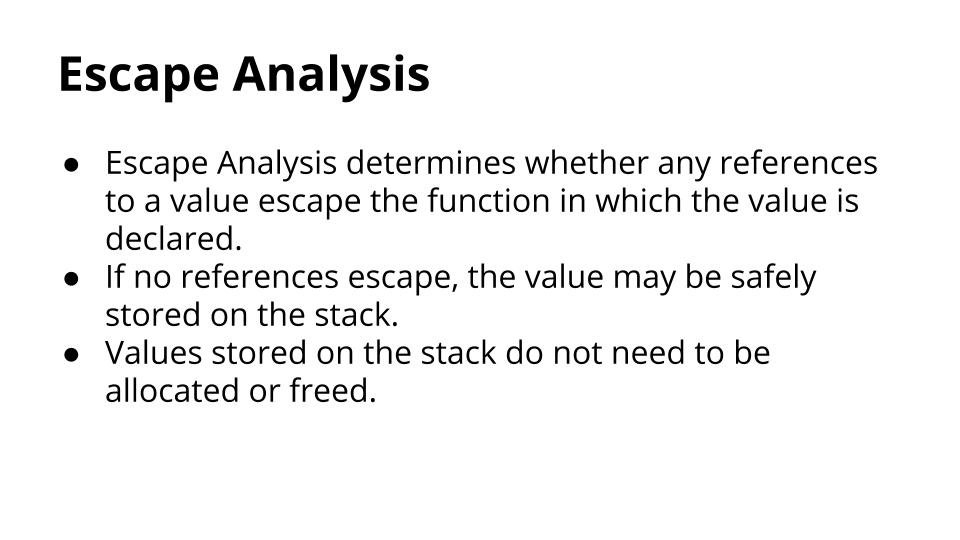

Escape analysis determines whether any references to a value escape the function in which the value is declared.

|

||||

|

||||

If no references escape, the value may be safely stored on the stack.

|

||||

|

||||

Values stored on the stack do not need to be allocated or freed.

|

||||

|

||||

Lets look at some examples

|

||||

|

||||

[][34]

|

||||

|

||||

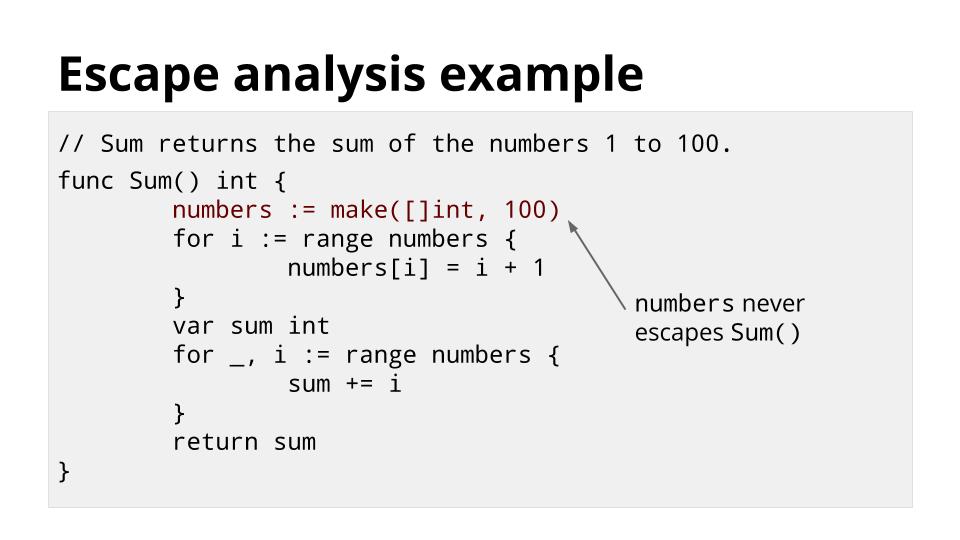

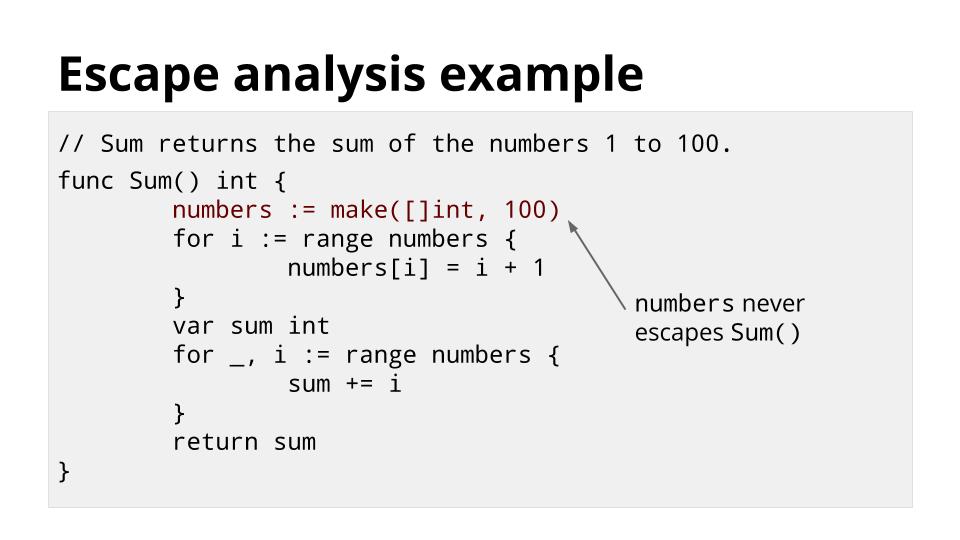

`Sum` adds the numbers between 1 and 100 and returns the result. This is a rather unusual way to do this, but it illustrates how Escape Analysis works.

|

||||

|

||||

Because the numbers slice is only referenced inside `Sum`, the compiler will arrange to store the 100 integers for that slice on the stack, rather than the heap.

|

||||

|

||||

There is no need to garbage collect `numbers`, it is automatically freed when `Sum` returns.

|

||||

|

||||

[][35]

|

||||

|

||||

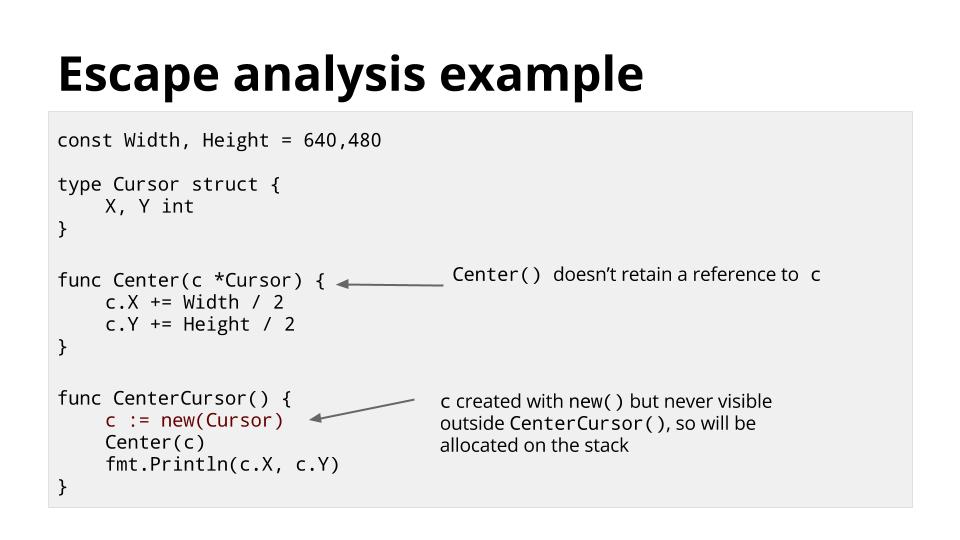

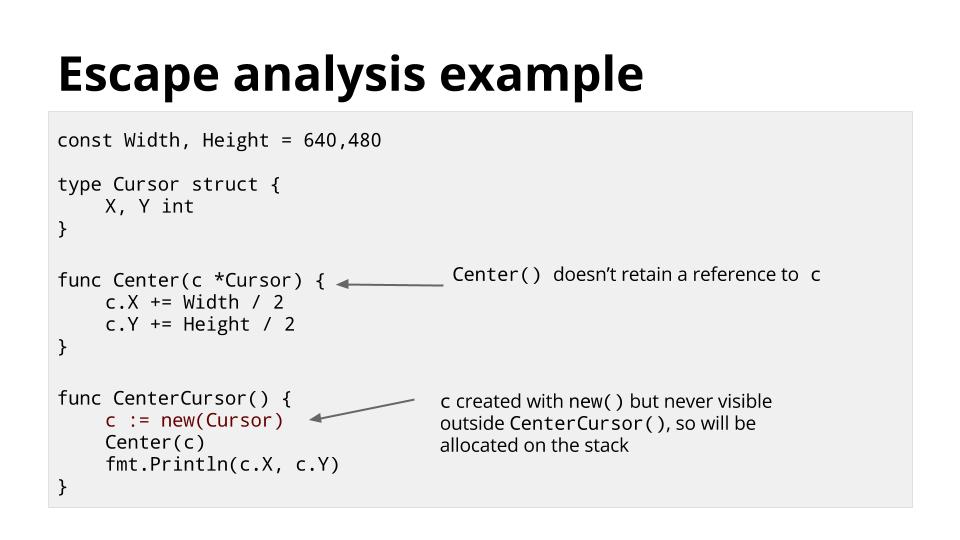

This second example is also a little contrived. In `CenterCursor` we create a new `Cursor` and store a pointer to it in c.

|

||||

|

||||

Then we pass `c` to the `Center()` function which moves the `Cursor` to the center of the screen.

|

||||

|

||||

Then finally we print the X and Y locations of that `Cursor`.

|

||||

|

||||

Even though `c` was allocated with the `new` function, it will not be stored on the heap, because no reference `c` escapes the `CenterCursor` function.

|

||||

|

||||

[][36]

|

||||

|

||||

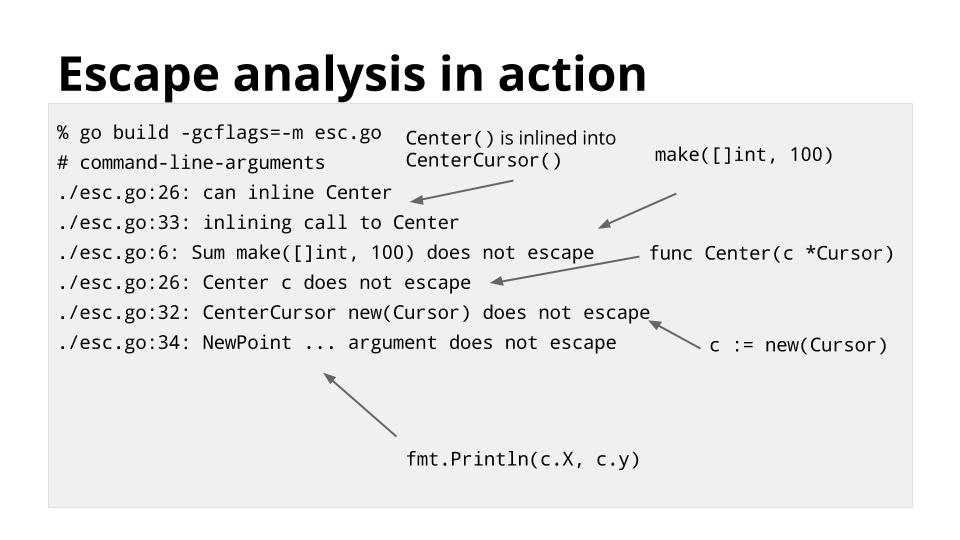

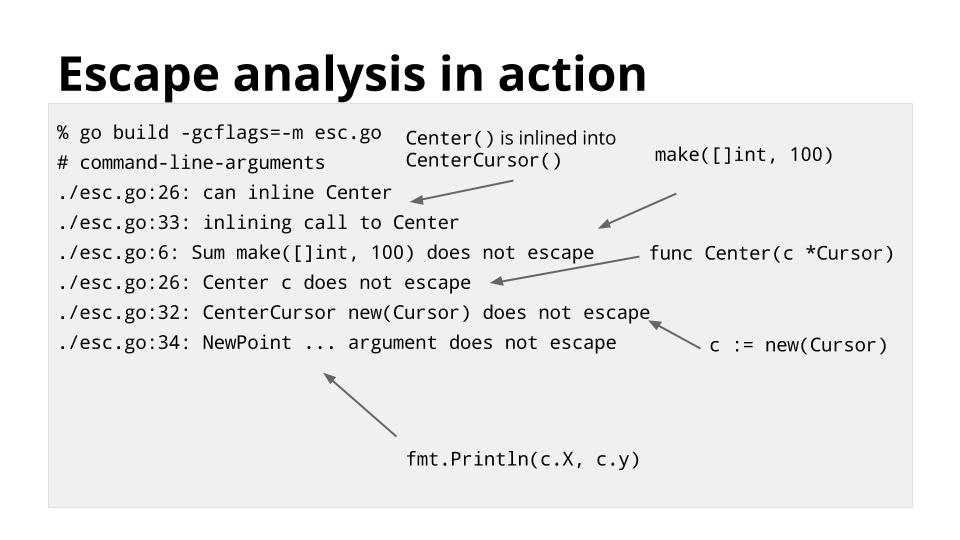

Go’s optimisations are always enabled by default. You can see the compiler’s escape analysis and inlining decisions with the `-gcflags=-m` switch.

|

||||

|

||||

Because escape analysis is performed at compile time, not run time, stack allocation will always be faster than heap allocation, no matter how efficient your garbage collector is.

|

||||

|

||||

I will talk more about the stack in the remaining sections of this talk.

|

||||

|

||||

[][37]

|

||||

|

||||

Go has goroutines. These are the foundations for concurrency in Go.

|

||||

|

||||

I want to step back for a moment and explore the history that leads us to goroutines.

|

||||

|

||||

In the beginning computers ran one process at a time. Then in the 60’s the idea of multiprocessing, or time sharing became popular.

|

||||

|

||||

In a time-sharing system the operating systems must constantly switch the attention of the CPU between these processes by recording the state of the current process, then restoring the state of another.

|

||||

|

||||

This is called _process switching_ .

|

||||

|

||||

[][38]

|

||||

|

||||

There are three main costs of a process switch.

|

||||

|

||||

First is the kernel needs to store the contents of all the CPU registers for that process, then restore the values for another process.

|

||||

|

||||

The kernel also needs to flush the CPU’s mappings from virtual memory to physical memory as these are only valid for the current process.

|

||||

|

||||

Finally there is the cost of the operating system context switch, and the overhead of the scheduler function to choose the next process to occupy the CPU.

|

||||

|

||||

[][39]

|

||||

|

||||

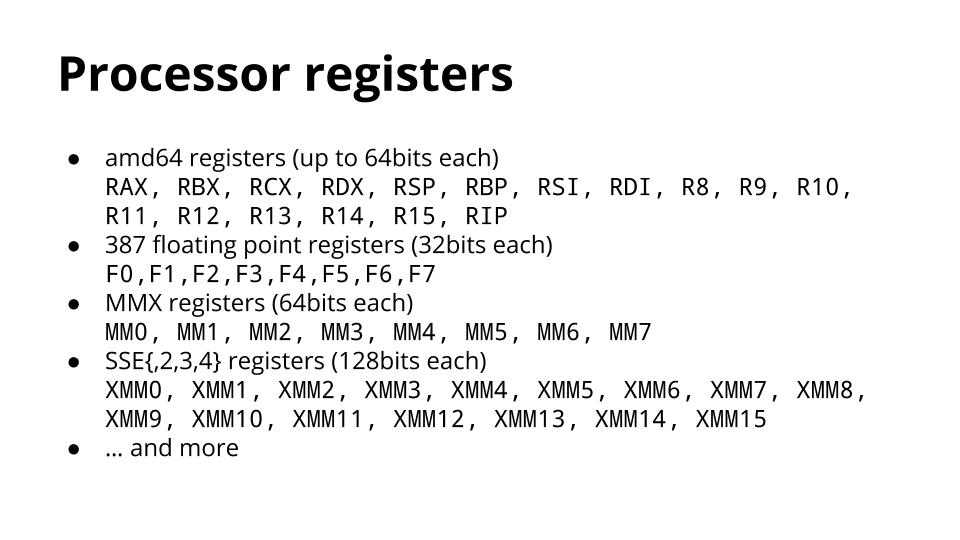

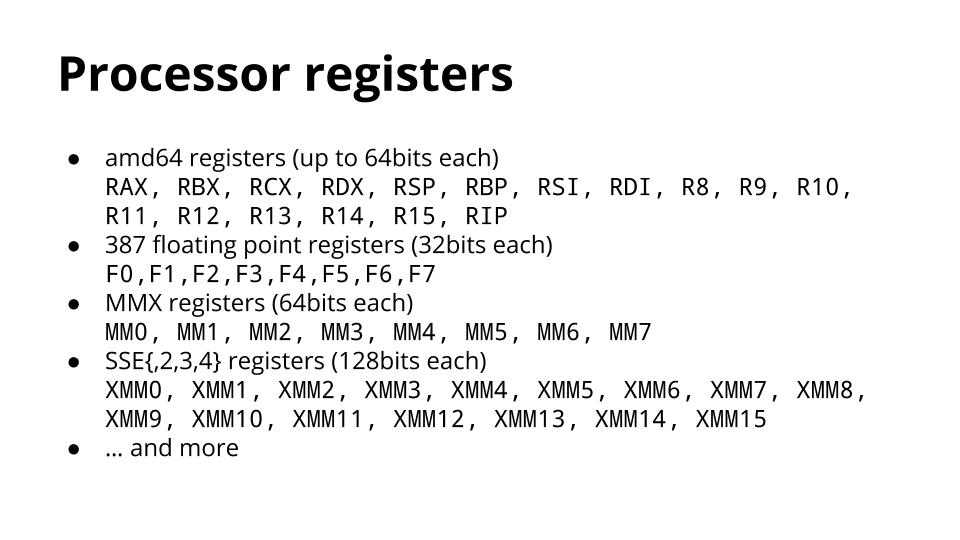

There are a surprising number of registers in a modern processor. I have difficulty fitting them on one slide, which should give you a clue how much time it takes to save and restore them.

|

||||

|

||||

Because a process switch can occur at any point in a process’ execution, the operating system needs to store the contents of all of these registers because it does not know which are currently in use.

|

||||

|

||||

[][40]

|

||||

|

||||

This lead to the development of threads, which are conceptually the same as processes, but share the same memory space.

|

||||

|

||||

As threads share address space, they are lighter than processes so are faster to create and faster to switch between.

|

||||

|

||||

[][41]

|

||||

|

||||

Goroutines take the idea of threads a step further.

|

||||

|

||||

Goroutines are cooperatively scheduled, rather than relying on the kernel to manage their time sharing.

|

||||

|

||||

The switch between goroutines only happens at well defined points, when an explicit call is made to the Go runtime scheduler.

|

||||

|

||||

The compiler knows the registers which are in use and saves them automatically.

|

||||

|

||||

[][42]

|

||||

|

||||

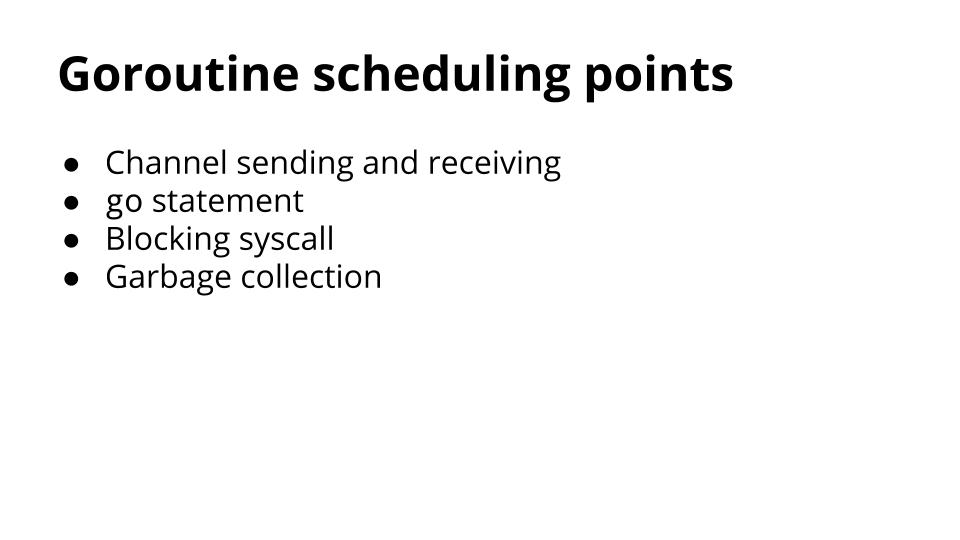

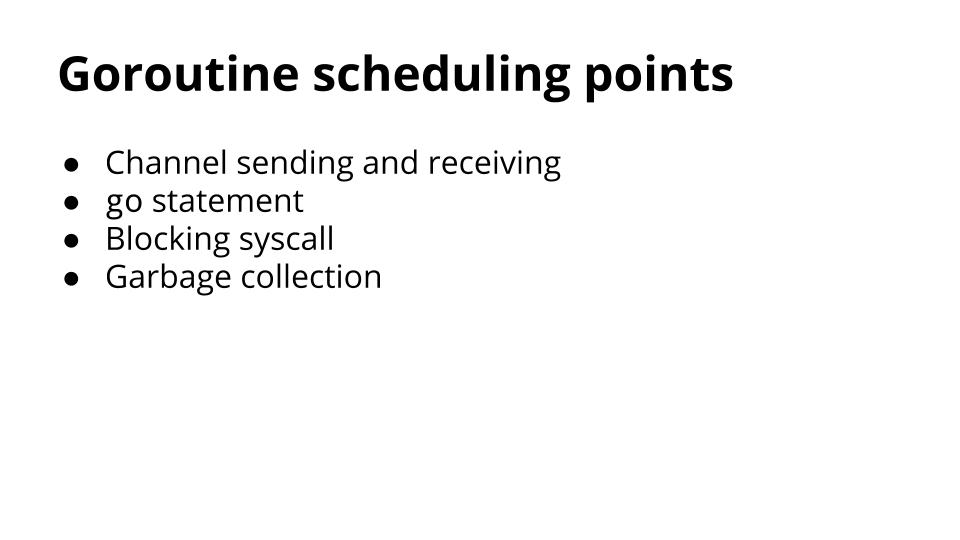

While goroutines are cooperatively scheduled, this scheduling is handled for you by the runtime.

|

||||

|

||||

Places where Goroutines may yield to others are:

|

||||

|

||||

* Channel send and receive operations, if those operations would block.

|

||||

|

||||

* The Go statement, although there is no guarantee that new goroutine will be scheduled immediately.

|

||||

|

||||

* Blocking syscalls like file and network operations.

|

||||

|

||||

* After being stopped for a garbage collection cycle.

|

||||

|

||||

[][43]

|

||||

|

||||

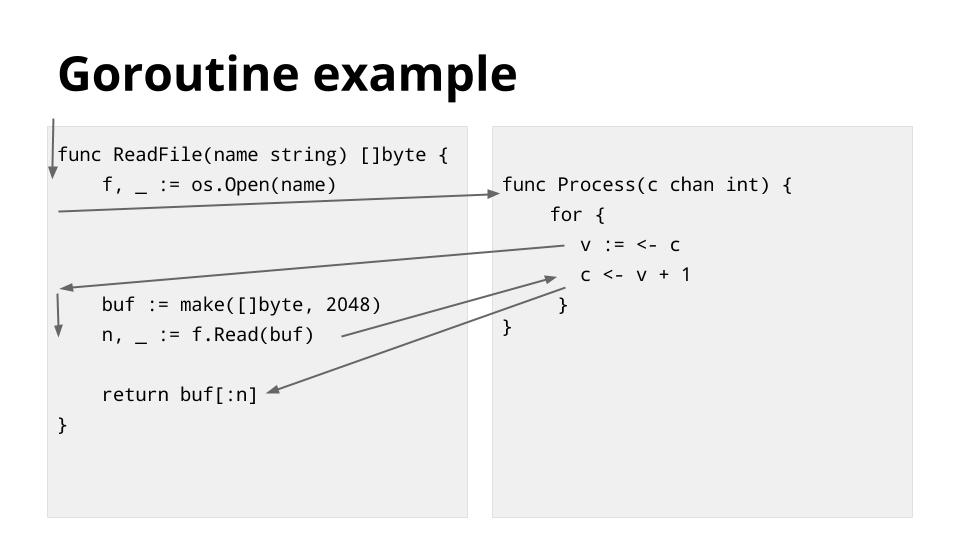

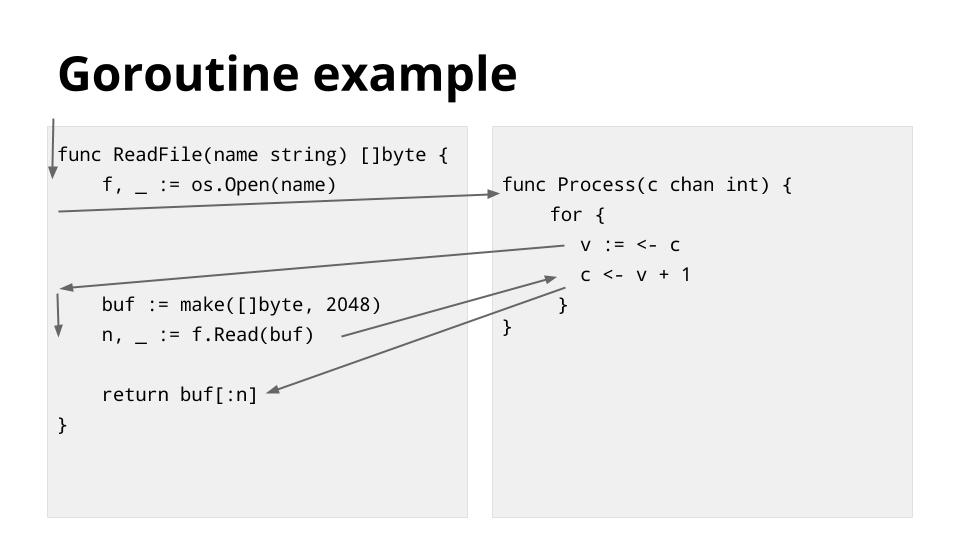

This an example to illustrate some of the scheduling points described in the previous slide.

|

||||

|

||||

The thread, depicted by the arrow, starts on the left in the `ReadFile` function. It encounters `os.Open`, which blocks the thread while waiting for the file operation to complete, so the scheduler switches the thread to the goroutine on the right hand side.

|

||||

|

||||

Execution continues until the read from the `c` chan blocks, and by this time the `os.Open` call has completed so the scheduler switches the thread back the left hand side and continues to the `file.Read` function, which again blocks on file IO.

|

||||

|

||||

The scheduler switches the thread back to the right hand side for another channel operation, which has unblocked during the time the left hand side was running, but it blocks again on the channel send.

|

||||

|

||||

Finally the thread switches back to the left hand side as the `Read` operation has completed and data is available.

|

||||

|

||||

[][44]

|

||||

|

||||

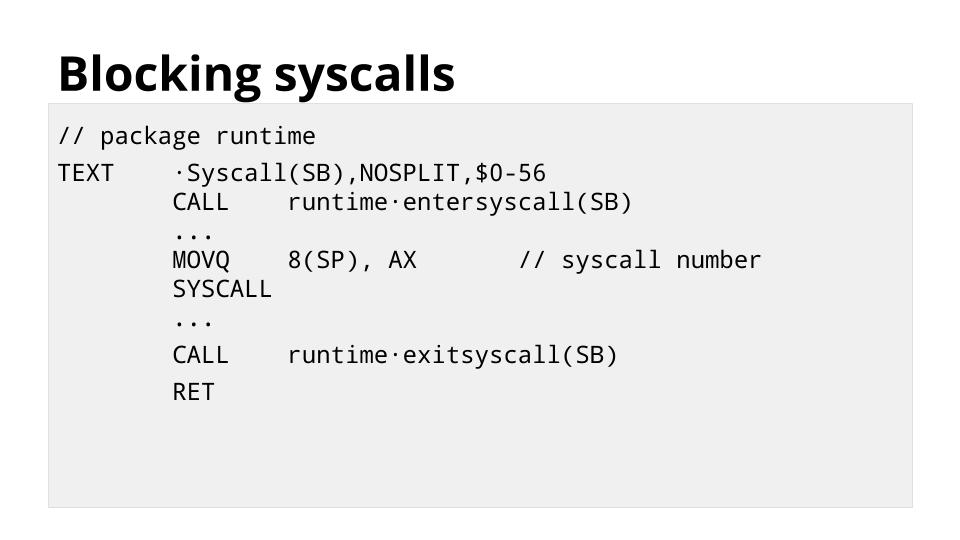

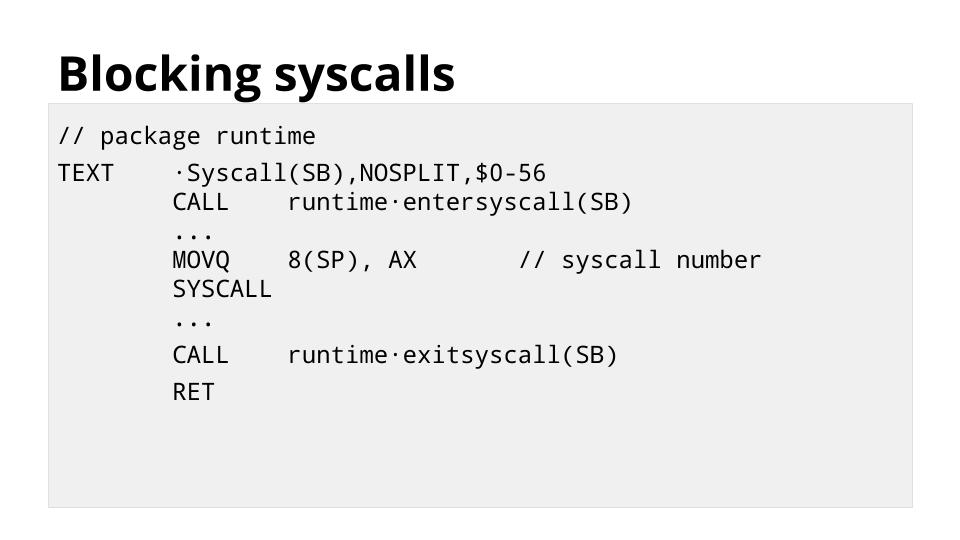

This slide shows the low level `runtime.Syscall` function which is the base for all functions in the os package.

|

||||

|

||||

Any time your code results in a call to the operating system, it will go through this function.

|

||||

|

||||

The call to `entersyscall` informs the runtime that this thread is about to block.

|

||||

|

||||

This allows the runtime to spin up a new thread which will service other goroutines while this current thread blocked.

|

||||

|

||||

This results in relatively few operating system threads per Go process, with the Go runtime taking care of assigning a runnable Goroutine to a free operating system thread.

|

||||

|

||||

[][45]

|

||||

|

||||

In the previous section I discussed how goroutines reduce the overhead of managing many, sometimes hundreds of thousands of concurrent threads of execution.

|

||||

|

||||

There is another side to the goroutine story, and that is stack management, which leads me to my final topic.

|

||||

|

||||

[][46]

|

||||

|

||||

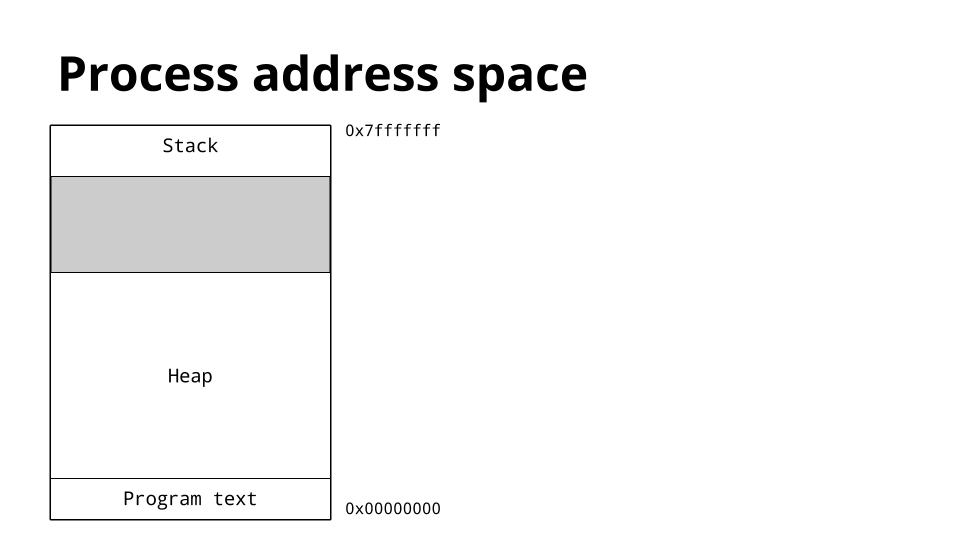

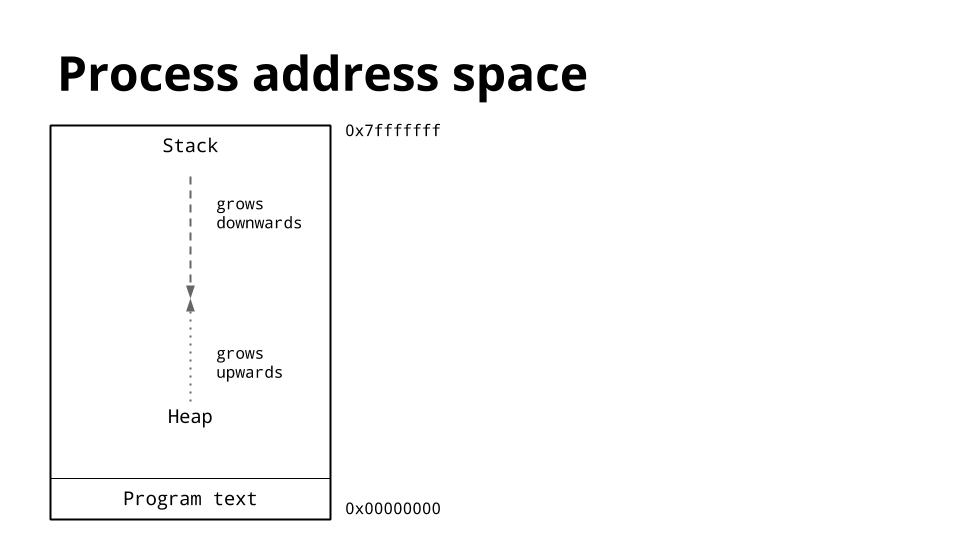

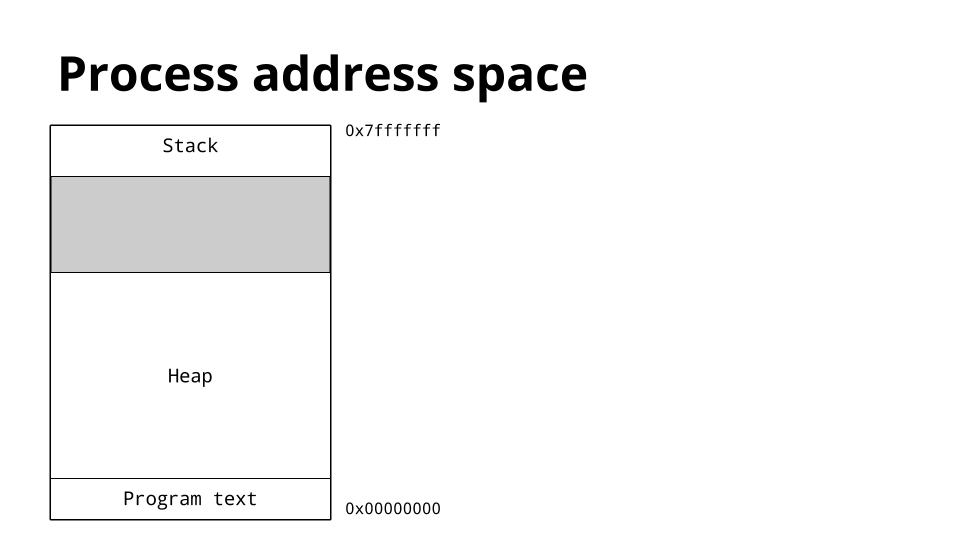

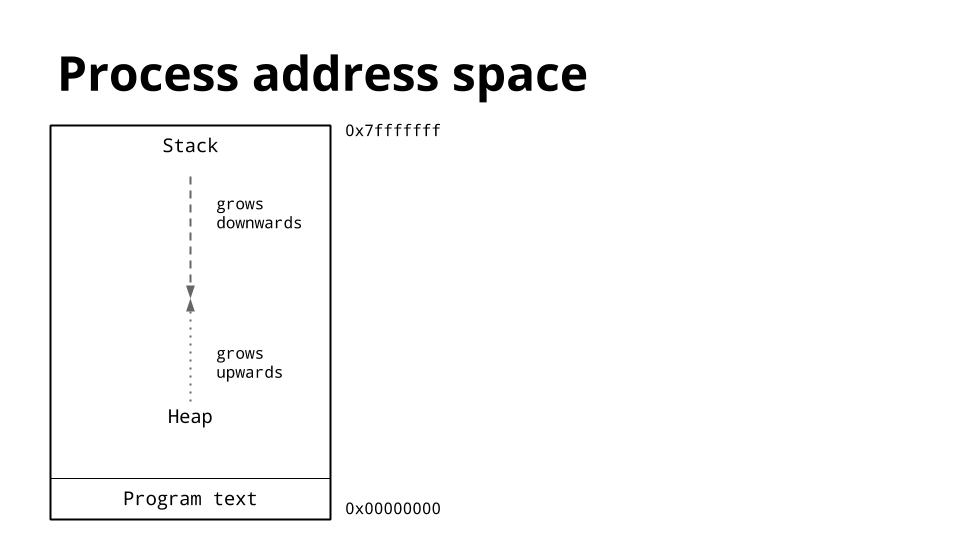

This is a diagram of the memory layout of a process. The key thing we are interested is the location of the heap and the stack.

|

||||

|

||||

Traditionally inside the address space of a process, the heap is at the bottom of memory, just above the program (text) and grows upwards.

|

||||

|

||||

The stack is located at the top of the virtual address space, and grows downwards.

|

||||

|

||||

[][47]

|

||||

|

||||

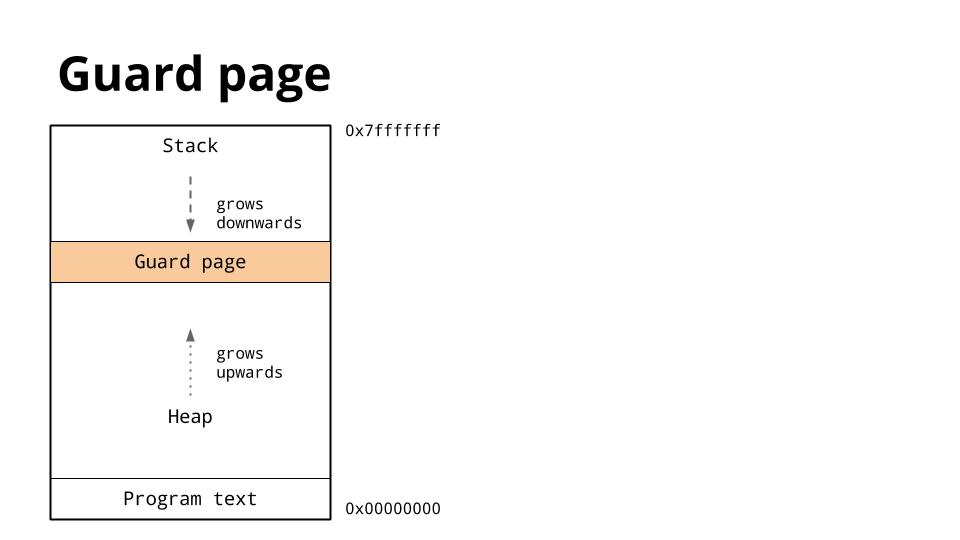

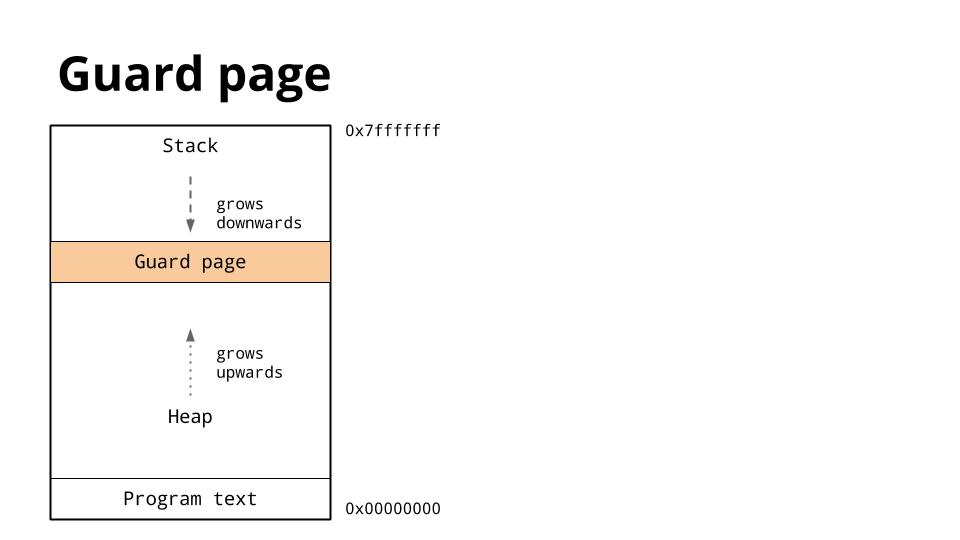

Because the heap and stack overwriting each other would be catastrophic, the operating system usually arranges to place an area of unwritable memory between the stack and the heap to ensure that if they did collide, the program will abort.

|

||||

|

||||

This is called a guard page, and effectively limits the stack size of a process, usually in the order of several megabytes.

|

||||

|

||||

[][48]

|

||||

|

||||

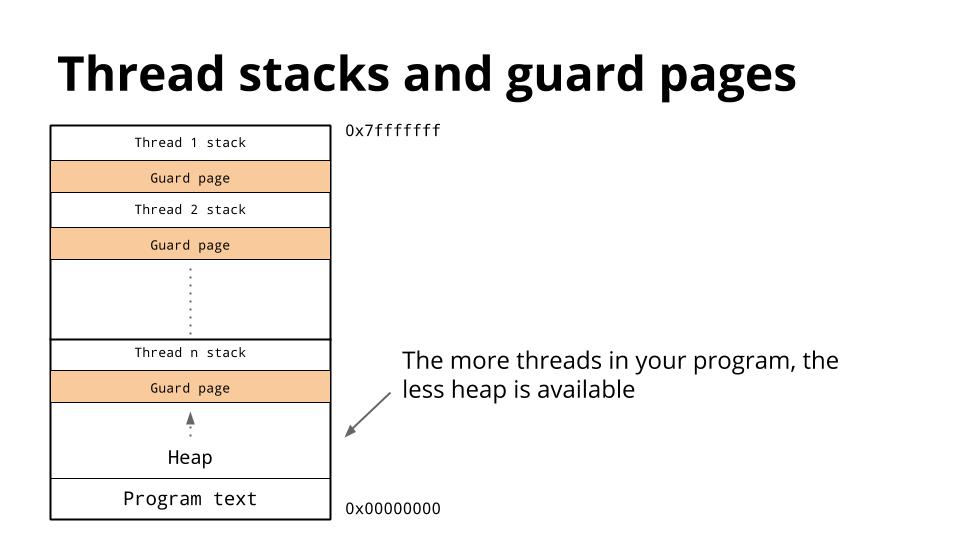

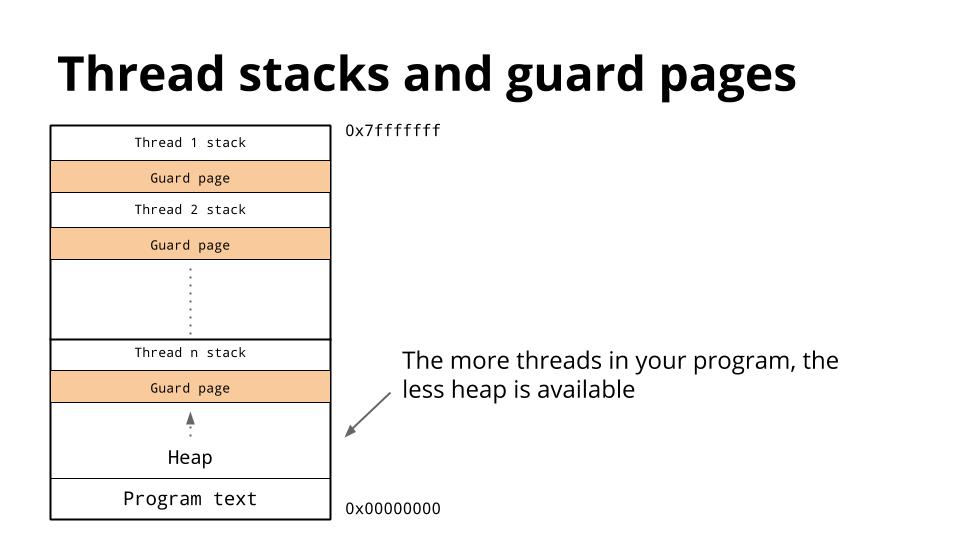

We’ve discussed that threads share the same address space, so for each thread, it must have its own stack.

|

||||

|

||||

Because it is hard to predict the stack requirements of a particular thread, a large amount of memory is reserved for each thread’s stack along with a guard page.

|

||||

|

||||

The hope is that this is more than will ever be needed and the guard page will never be hit.

|

||||

|

||||

The downside is that as the number of threads in your program increases, the amount of available address space is reduced.

|

||||

|

||||

[][49]

|

||||

|

||||

We’ve seen that the Go runtime schedules a large number of goroutines onto a small number of threads, but what about the stack requirements of those goroutines ?

|

||||

|

||||

Instead of using guard pages, the Go compiler inserts a check as part of every function call to check if there is sufficient stack for the function to run. If there is not, the runtime can allocate more stack space.

|

||||

|

||||

Because of this check, a goroutines initial stack can be made much smaller, which in turn permits Go programmers to treat goroutines as cheap resources.

|

||||

|

||||

[][50]

|

||||

|

||||

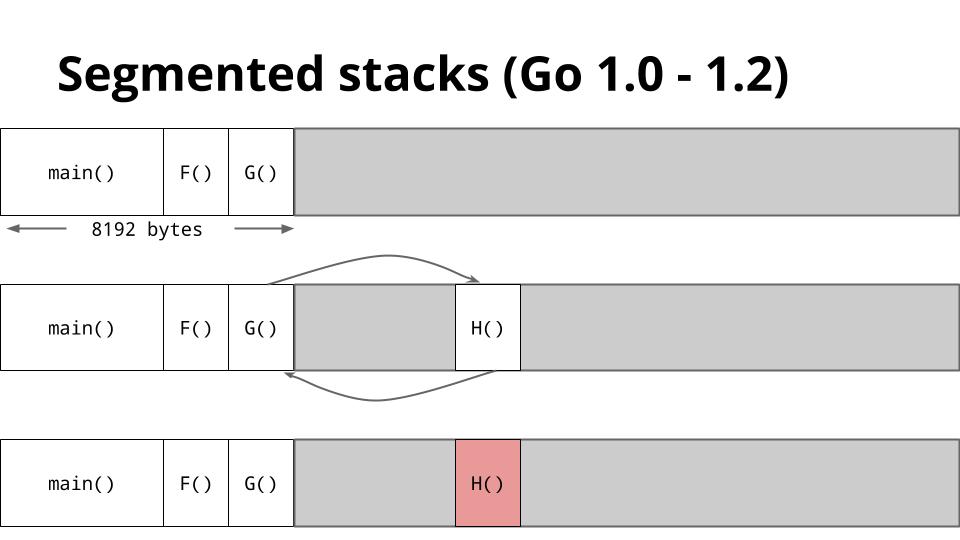

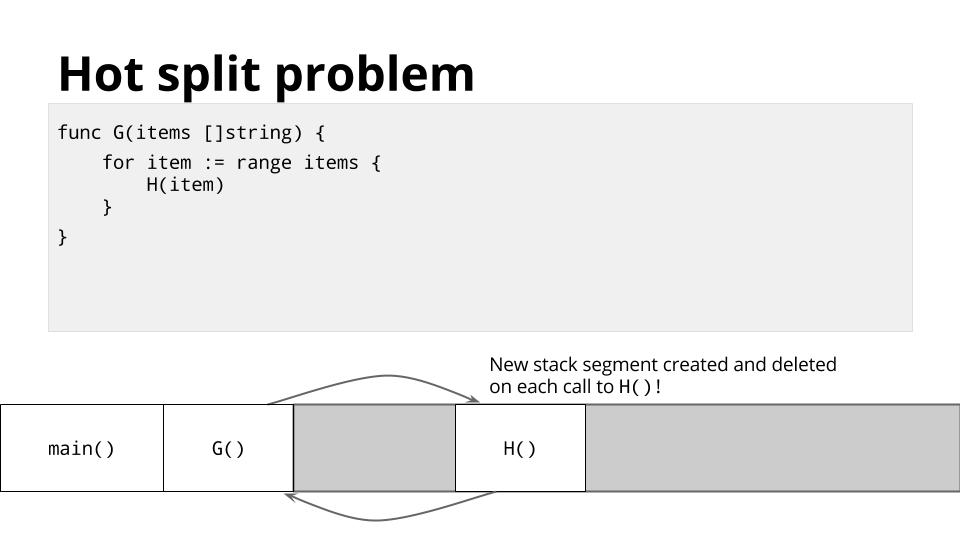

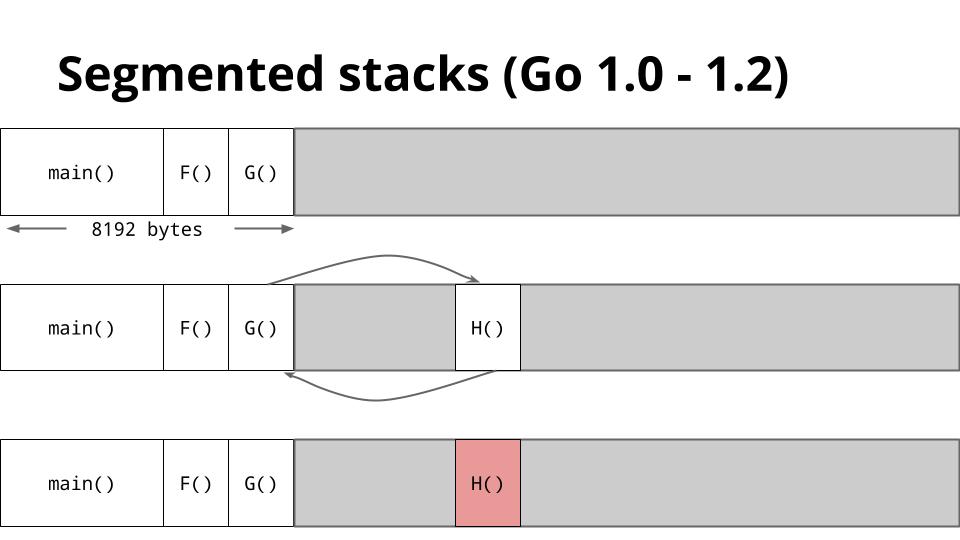

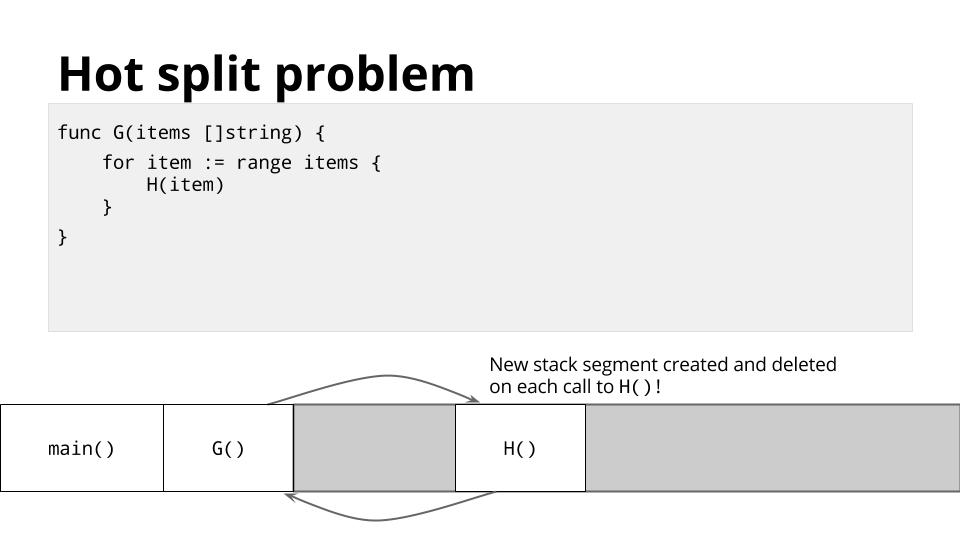

This is a slide that shows how stacks are managed in Go 1.2.

|

||||

|

||||

When `G` calls to `H` there is not enough space for `H` to run, so the runtime allocates a new stack frame from the heap, then runs `H` on that new stack segment. When `H` returns, the stack area is returned to the heap before returning to `G`.

|

||||

|

||||

[][51]

|

||||

|

||||

This method of managing the stack works well in general, but for certain types of code, usually recursive code, it can cause the inner loop of your program to straddle one of these stack boundaries.

|

||||

|

||||

For example, in the inner loop of your program, function `G` may call `H` many times in a loop,

|

||||

|

||||

Each time this will cause a stack split. This is known as the hot split problem.

|

||||

|

||||

[][52]

|

||||

|

||||

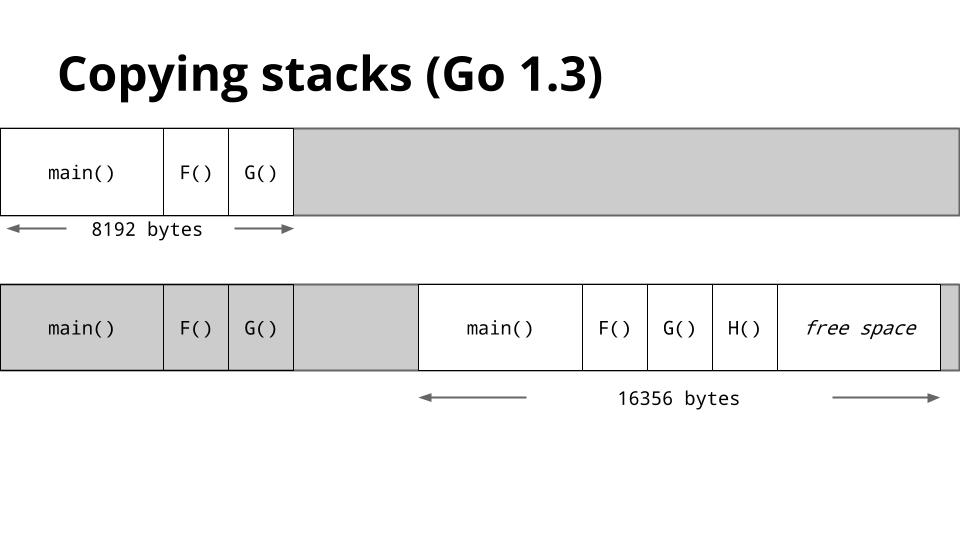

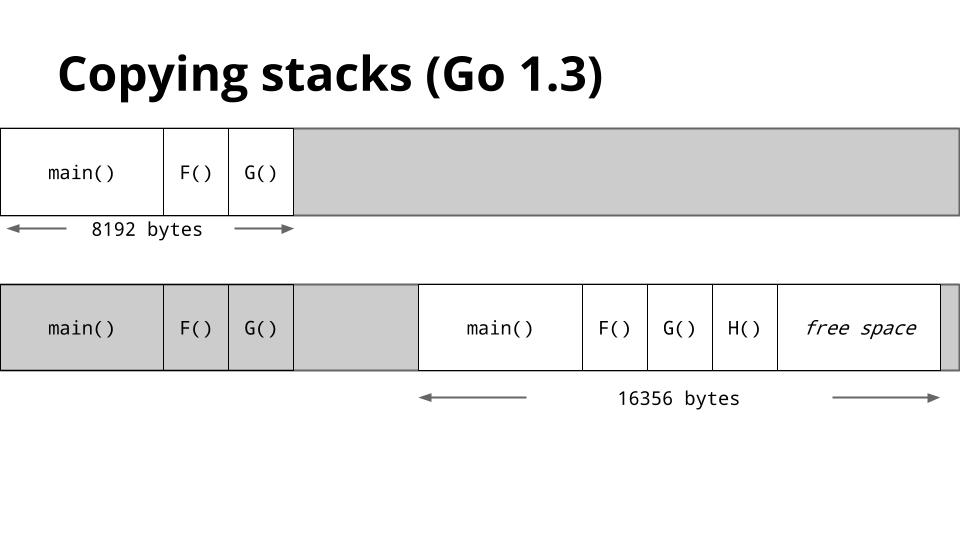

To solve hot splits, Go 1.3 has adopted a new stack management method.

|

||||

|

||||

Instead of adding and removing additional stack segments, if the stack of a goroutine is too small, a new, larger, stack will be allocated.

|

||||

|

||||

The old stack’s contents are copied to the new stack, then the goroutine continues with its new larger stack.

|

||||

|

||||

After the first call to `H` the stack will be large enough that the check for available stack space will always succeed.

|

||||

|

||||

This resolves the hot split problem.

|

||||

|

||||

[][53]

|

||||

|

||||

Values, Inlining, Escape Analysis, Goroutines, and segmented/copying stacks.

|

||||

|

||||

These are the five features that I chose to speak about today, but they are by no means the only things that makes Go a fast programming language, just as there more that three reasons that people cite as their reason to learn Go.

|

||||

|

||||

As powerful as these five features are individually, they do not exist in isolation.

|

||||

|

||||

For example, the way the runtime multiplexes goroutines onto threads would not be nearly as efficient without growable stacks.

|

||||

|

||||

Inlining reduces the cost of the stack size check by combining smaller functions into larger ones.

|

||||

|

||||

Escape analysis reduces the pressure on the garbage collector by automatically moving allocations from the heap to the stack.

|

||||

|

||||

Escape analysis is also provides better cache locality.

|

||||

|

||||

Without growable stacks, escape analysis might place too much pressure on the stack.

|

||||

|

||||

[][54]

|

||||

|

||||

* Thank you to the Gocon organisers for permitting me to speak today

|

||||

* twitter / web / email details

|

||||

* thanks to @offbymany, @billkennedy_go, and Minux for their assistance in preparing this talk.

|

||||

|

||||

### Related Posts:

|

||||

|

||||

1. [Hear me speak about Go performance at OSCON][1]

|

||||

|

||||

2. [Why is a Goroutine’s stack infinite ?][2]

|

||||

|

||||

3. [A whirlwind tour of Go’s runtime environment variables][3]

|

||||

|

||||

4. [Performance without the event loop][4]

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

作者简介:

|

||||

|

||||

David is a programmer and author from Sydney Australia.

|

||||

|

||||

Go contributor since February 2011, committer since April 2012.

|

||||

|

||||

Contact information

|

||||

|

||||

* dave@cheney.net

|

||||

* twitter: @davecheney

|

||||

|

||||

----------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://dave.cheney.net/2014/06/07/five-things-that-make-go-fast

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Dave Cheney ][a]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:https://dave.cheney.net/

|

||||

[1]:https://dave.cheney.net/2015/05/31/hear-me-speak-about-go-performance-at-oscon

|

||||

[2]:https://dave.cheney.net/2013/06/02/why-is-a-goroutines-stack-infinite

|

||||

[3]:https://dave.cheney.net/2015/11/29/a-whirlwind-tour-of-gos-runtime-environment-variables

|

||||

[4]:https://dave.cheney.net/2015/08/08/performance-without-the-event-loop

|

||||

[5]:http://mindchunk.blogspot.com.au/2014/06/remixing-with-deck.html

|

||||

[6]:http://ymotongpoo.hatenablog.com/entry/2014/06/01/124350

|

||||

[7]:http://www.goinggo.net/

|

||||

[8]:https://twitter.com/offbymany

|

||||

[9]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-1.jpg

|

||||

[10]:https://dave.cheney.net/2014/06/07/five-things-that-make-go-fast/gocon-2014-2

|

||||

[11]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-3.jpg

|

||||

[12]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-4.jpg

|

||||

[13]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-5.jpg

|

||||

[14]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-6.jpg

|

||||

[15]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-7.jpg

|

||||

[16]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-8.jpg

|

||||

[17]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-9.jpg

|

||||

[18]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-10.jpg

|

||||

[19]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-11.jpg

|

||||

[20]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-12.jpg

|

||||

[21]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-13.jpg

|

||||

[22]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-14.jpg

|

||||

[23]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-15.jpg

|

||||

[24]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-16.jpg

|

||||

[25]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-17.jpg

|

||||

[26]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-18.jpg

|

||||

[27]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-19.jpg

|

||||

[28]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-20.jpg

|

||||

[29]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-21.jpg

|

||||

[30]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-22.jpg

|

||||

[31]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-23.jpg

|

||||

[32]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-24.jpg

|

||||

[33]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-25.jpg

|

||||

[34]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-26.jpg

|

||||

[35]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-27.jpg

|

||||

[36]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-28.jpg

|

||||

[37]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-30.jpg

|

||||

[38]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-29.jpg

|

||||

[39]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-31.jpg

|

||||

[40]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-32.jpg

|

||||

[41]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-33.jpg

|

||||

[42]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-34.jpg

|

||||

[43]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-35.jpg

|

||||

[44]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-36.jpg

|

||||

[45]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-37.jpg

|

||||

[46]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-39.jpg

|

||||

[47]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-40.jpg

|

||||

[48]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-41.jpg

|

||||

[49]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-42.jpg

|

||||

[50]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-43.jpg

|

||||

[51]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-44.jpg

|

||||

[52]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-45.jpg

|

||||

[53]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-46.jpg

|

||||

[54]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-47.jpg

|

||||

494

translated/tech/20140607 Five things that make Go fast.md

Normal file

494

translated/tech/20140607 Five things that make Go fast.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,494 @@

|

||||

五种加速 Go 的特性

|

||||

============================================================

|

||||

|

||||

_Anthony Starks 使用他出色的 Deck 演示工具重构了我原来的基于 Google Slides 的幻灯片。你可以在他的博客上查看他重构后的幻灯片, [mindchunk.blogspot.com.au/2014/06/remixing-with-deck][5]._

|

||||

|

||||

* * *

|

||||

|

||||

我最近被邀请在 Gocon 发表演讲,这是一个每半年在日本东京举行的精彩 Go 的大会。[Gocon 2014][6] 是一个完全由社区驱动的为期一天的活动,由培训和一整个下午的围绕着 <q style="border: 0px; vertical-align: baseline; quotes: none;">生产环境中的 Go</q> 这个主题的演讲组成.

|

||||

|

||||

以下是我的讲义。原文的结构能让我缓慢而清晰的演讲,因此我已经编辑了它使其更可读。

|

||||

|

||||

我要感谢 [Bill Kennedy][7] 和 Minux Ma,特别是 [Josh Bleecher Snyder][8],感谢他们在我准备这次演讲中的帮助。

|

||||

|

||||

* * *

|

||||

|

||||

大家下午好。

|

||||

|

||||

我叫 David.

|

||||

|

||||

我很高兴今天能来到 Gocon。我想参加这个会议已经两年了,我很感谢主办方能提供给我向你们演讲的机会。

|

||||

|

||||

[][9]

|

||||

我想以一个问题开始我的演讲。

|

||||

|

||||

为什么选择 Go?

|

||||

|

||||

当大家讨论学习或在生产环境中使用 Go 的原因时,答案不一而足,但因为以下三个原因的最多。

|

||||

|

||||

[][10]

|

||||

这就是 TOP3 的原因。

|

||||

|

||||

第一,并发。

|

||||

|

||||

Go 的 <ruby>并发原语<rt>Concurrency Primitives</rt></ruby> 对于来自 Nodejs,Ruby 或 Python 等单线程脚本语言的程序员,或者来自 C++ 或 Java 等重量级线程模型的语言都很有吸引力。

|

||||

|

||||

易于部署。

|

||||

|

||||

我们今天从经验丰富的 Gophers 那里听说过,他们非常欣赏部署 Go 应用的简单性。

|

||||

|

||||

[][11]

|

||||

|

||||

然后是性能。

|

||||

|

||||

我相信人们选择 Go 的一个重要原因是它 _快_。

|

||||

|

||||

[][12]

|

||||

|

||||

在今天的演讲中,我想讨论五个有助于提高 Go 性能的特性。

|

||||

|

||||

我还将与大家分享 Go 如何实现这些特性的细节。

|

||||

|

||||

[][13]

|

||||

|

||||

我要谈的第一个特性是 Go 对于值的高效处理和存储。

|

||||

|

||||

[][14]

|

||||

|

||||

这是 Go 中一个值的例子。编译时,`gocon` 正好消耗四个字节的内存。

|

||||

|

||||

让我们将 Go 与其他一些语言进行比较

|

||||

|

||||

[][15]

|

||||

|

||||

由于 Python 表示变量的方式的开销,使用 Python 存储相同的值会消耗六倍的内存。

|

||||

|

||||

Python 使用额外的内存来跟踪类型信息,进行 <ruby>引用计数<rt>Reference Counting</rt></ruby> 等。

|

||||

|

||||

让我们看另一个例子:

|

||||

|

||||

[][16]

|

||||

|

||||

与 Go 类似,Java 消耗 4 个字节的内存来存储 `int` 型。

|

||||

|

||||

但是,要在像 `List` 或 `Map` 这样的集合中使用此值,编译器必须将其转换为 `Integer` 对象。

|

||||

|

||||

[][17]

|

||||

|

||||

因此,Java 中的整数通常消耗 16 到 24 个字节的内存。

|

||||

|

||||

为什么这很重要? 内存便宜且充足,为什么这个开销很重要?

|

||||

|

||||

[][18]

|

||||

|

||||

这是一张显示 CPU 时钟速度与内存总线速度的图表。

|

||||

|

||||

请注意 CPU 时钟速度和内存总线速度之间的差距如何继续扩大。

|

||||

|

||||

两者之间的差异实际上是 CPU 花费多少时间等待内存。

|

||||

|

||||

[][19]

|

||||

|

||||

自 1960 年代后期以来,CPU 设计师已经意识到了这个问题。

|

||||

|

||||

他们的解决方案是一个缓存,一个更小,更快的内存区域,介入 CPU 和主存之间。

|

||||

|

||||

[][20]

|

||||

|

||||

这是一个 `Location` 类型,它保存物体在三维空间中的位置。它是用 Go 编写的,因此每个 `Location` 只消耗 24 个字节的存储空间。

|

||||

|

||||

我们可以使用这种类型来构造一个容纳 1000 个 `Location` 的数组类型,它只消耗 24000 字节的内存。

|

||||

|

||||

在数组内部,`Location` 结构体是顺序存储的,而不是随机存储的 1000 个 `Location` 结构体的指针。

|

||||

|

||||

这很重要,因为现在所有 1000 个 `Location` 结构体都按顺序放在缓存中,紧密排列在一起。

|

||||

|

||||

[][21]

|

||||

|

||||

Go 允许您创建紧凑的数据结构,避免不必要的填充字节。

|

||||

|

||||

紧凑的数据结构能更好地利用缓存。

|

||||

|

||||

更好的缓存利用率可带来更好的性能。

|

||||

|

||||

[][22]

|

||||

|

||||

函数调用不是无开销的。

|

||||

|

||||

[][23]

|

||||

|

||||

调用函数时会发生三件事。

|

||||

|

||||

创建一个新的 <ruby>栈帧<rt>Stack Frame</rt></ruby>,并记录调用者的详细信息。

|

||||

|

||||

在函数调用期间可能被覆盖的任何寄存器都将保存到栈中。

|

||||

|

||||

处理器计算函数的地址并执行到该新地址的分支。

|

||||

|

||||

[][24]

|

||||

|

||||

由于函数调用是非常常见的操作,因此 CPU 设计师一直在努力优化此过程,但他们无法消除开销。

|

||||

|

||||

函调固有开销,或重于泰山,或轻于鸿毛,这取决于函数做了什么。

|

||||

|

||||

减少函数调用开销的解决方案是 <ruby>内联<rt>Inlining</rt></ruby>。

|

||||

|

||||

[][25]

|

||||

|

||||

Go 编译器通过将函数体视为调用者的一部分来内联函数。

|

||||

|

||||

内联也有成本,它增加了二进制文件大小。

|

||||

|

||||

只有当调用开销与函数所做工作关联度的很大时内联才有意义,因此只有简单的函数才能用于内联。

|

||||

|

||||

复杂的函数通常不受调用它们的开销所支配,因此不会内联。

|

||||

|

||||

[][26]

|

||||

|

||||

这个例子显示函数 `Double` 调用 `util.Max`。

|

||||

|

||||

为了减少调用 `util.Max` 的开销,编译器可以将 `util.Max` 内联到 `Double` 中,就象这样

|

||||

|

||||

[][27]

|

||||

|

||||

内联后不再调用 `util.Max`,但是 `Double` 的行为没有改变。

|

||||

|

||||

内联并不是 Go 独有的。几乎每种编译或及时编译的语言都执行此优化。但是 Go 的内联是如何实现的?

|

||||

|

||||

Go 实现非常简单。编译包时,会标记任何适合内联的小函数,然后照常编译。

|

||||

|

||||

然后函数的源代码和编译后版本都会被存储。

|

||||

|

||||

[][28]

|

||||

|

||||

此幻灯片显示了 `util.a` 的内容。源代码已经过一些转换,以便编译器更容易快速处理。

|

||||

|

||||

当编译器编译 `Double` 时,它看到 `util.Max` 可内联的,并且 `util.Max` 的源代码是可用的。

|

||||

|

||||

就会替换原函数中的代码,而不是插入对 `util.Max` 的编译版本的调用。

|

||||

|

||||

拥有该函数的源代码可以实现其他优化。

|

||||

|

||||

[][29]

|

||||

|

||||

在这个例子中,尽管函数 `Test` 总是返回 `false`,但 `Expensive` 在不执行它的情况下无法知道结果。

|

||||

|

||||

当 `Test` 被内联时,我们得到这样的东西

|

||||

|

||||

[][30]

|

||||

|

||||

编译器现在知道 `Expensive` 的代码无法访问。

|

||||

|

||||

这不仅节省了调用 `Test` 的成本,还节省了编译或运行任何现在无法访问的 `Expensive` 代码。

|

||||

|

||||

Go 编译器可以跨文件甚至跨包自动内联函数。还包括从标准库调用的可内联函数的代码。

|

||||

|

||||

[][31]

|

||||

|

||||

<ruby>强制垃圾回收<rt>Mandatory Garbage Collection</rt></ruby> 使 Go 成为一种更简单,更安全的语言。

|

||||

|

||||

这并不意味着垃圾回收会使 Go 变慢,或者垃圾回收是程序速度的瓶颈。

|

||||

|

||||

这意味着在堆上分配的内存是有代价的。每次 GC 运行时都会花费 CPU 时间,直到释放内存为止。

|

||||

|

||||

[][32]

|

||||

|

||||

然而,有另一个地方分配内存,那就是栈。

|

||||

|

||||

与 C 不同,它强制您选择是否将值通过 `malloc` 将其存储在堆上,还是通过在函数范围内声明将其储存在栈上;Go 实现了一个名为 <ruby>逃逸分析<rt>Escape Analysis</rt></ruby> 的优化。

|

||||

|

||||

[][33]

|

||||

|

||||

逃逸分析决定了对一个值的任何引用是否会从被声明的函数中逃逸。

|

||||

|

||||

如果没有引用逃逸,则该值可以安全地存储在栈中。

|

||||

|

||||

存储在栈中的值不需要分配或释放。

|

||||

|

||||

让我们看一些例子

|

||||

|

||||

[][34]

|

||||

|

||||

`Sum` 返回 1 到 100 的整数的和。这是一种相当不寻常的做法,但它说明了逃逸分析的工作原理。

|

||||

|

||||

因为切片 `numbers` 仅在 `Sum` 内引用,所以编译器将安排到栈上来存储的 100 个整数,而不是安排到堆上。

|

||||

|

||||

没有必要回收 `numbers`,它会在 `Sum` 返回时自动释放。

|

||||

|

||||

[][35]

|

||||

|

||||

第二个例子也有点尬。在 `CenterCursor` 中,我们创建一个新的 `Cursor` 对象并在 `c` 中存储指向它的指针。

|

||||

|

||||

然后我们将 `c` 传递给 `Center()` 函数,它将 `Cursor` 移动到屏幕的中心。

|

||||

|

||||

最后我们打印出那个 'Cursor` 的 X 和 Y 坐标。

|

||||

|

||||

即使 `c` 被 `new` 函数分配了空间,它也不会存储在堆上,因为没有引用 `c` 的变量逃逸 `CenterCursor` 函数。

|

||||

|

||||

[][36]

|

||||

|

||||

默认情况下,Go 的优化始终处于启用状态。可以使用 `-gcflags = -m` 开关查看编译器的逃逸分析和内联决策。

|

||||

|

||||

因为逃逸分析是在编译时执行的,而不是运行时,所以无论垃圾回收的效率如何,栈分配总是比堆分配快。

|

||||

|

||||

我将在本演讲的其余部分详细讨论栈。

|

||||

|

||||

[][37]

|

||||

|

||||

Go 有 goroutines。 这是 Go 并发的基石。

|

||||

|

||||

我想退一步,探索 goroutines 的历史。

|

||||

|

||||

最初,计算机一次运行一个进程。在 60 年代,多进程或 <ruby>分时<rt>Time Sharing</rt></ruby> 的想法变得流行起来。

|

||||

|

||||

在分时系统中,操作系统必须通过保护当前进程的现场,然后恢复另一个进程的现场,不断地在这些进程之间切换 CPU 的注意力。

|

||||

|

||||

这称为 _进程切换_。

|

||||

|

||||

[][38]

|

||||

|

||||

进程切换有三个主要开销。

|

||||

|

||||

首先,内核需要保护该进程的所有 CPU 寄存器的现场,然后恢复另一个进程的现场。

|

||||

|

||||

内核还需要将 CPU 的映射从虚拟内存刷新到物理内存,因为这些映射仅对当前进程有效。

|

||||

|

||||

最后是操作系统 <ruby>上下文切换<rt>Context Switch</rt></ruby> 的成本,以及 <ruby>调度函数<rt>Scheduler Function</rt></ruby> 选择占用 CPU 的下一个进程的开销。

|

||||

|

||||

[][39]

|

||||

|

||||

现代处理器中有数量惊人的寄存器。我很难在一张幻灯片上排开它们,这可以让你知道保护和恢复它们需要多少时间。

|

||||

|

||||

由于进程切换可以在进程执行的任何时刻发生,因此操作系统需要存储所有寄存器的内容,因为它不知道当前正在使用哪些寄存器。

|

||||

|

||||

[][40]

|

||||

|

||||

这导致了线程的出生,这些线程在概念上与进程相同,但共享相同的内存空间。

|

||||

|

||||

由于线程共享地址空间,因此它们比进程更轻,因此创建速度更快,切换速度更快。

|

||||

|

||||

[][41]

|

||||

|

||||

Goroutines 升华了线程的思想。

|

||||

|

||||

Goroutines 是 <ruby>协作式调度<rt>Cooperative Scheduled

|

||||

</rt></ruby>的,而不是依靠内核来调度。

|

||||

|

||||

当对 Go <ruby>运行时调度器<rt>Runtime Scheduler</rt></ruby> 进行显式调用时,goroutine 之间的切换仅发生在明确定义的点上。

|

||||

|

||||

编译器知道正在使用的寄存器并自动保存它们。

|

||||

|

||||

[][42]

|

||||

|

||||

虽然 goroutine 是协作式调度的,但运行时会为你处理。

|

||||

|

||||

Goroutines 可能会给禅让给其他协程时刻是:

|

||||

|

||||

* 阻塞式通道发送和接收。

|

||||

|

||||

* Go 声明,虽然不能保证会立即调度新的 goroutine。

|

||||

|

||||

* 文件和网络操作式的阻塞式系统调用。

|

||||

|

||||

* 在被垃圾回收循环停止后。

|

||||

|

||||

[][43]

|

||||

|

||||

这个例子说明了上一张幻灯片中描述的一些调度点。

|

||||

|

||||

箭头所示的线程从左侧的 `ReadFile` 函数开始。遇到 `os.Open`,它在等待文件操作完成时阻塞线程,因此调度器将线程切换到右侧的 goroutine。

|

||||

|

||||

继续执行直到从通道 `c` 中读,并且此时 `os.Open` 调用已完成,因此调度器将线程切换回左侧并继续执行 `file.Read` 函数,然后又被文件 IO 阻塞。

|

||||

|

||||

调度器将线程切换回右侧以进行另一个通道操作,该操作在左侧运行期间已解锁,但在通道发送时再次阻塞。

|

||||

|

||||

最后,当 `Read` 操作完成并且数据可用时,线程切换回左侧。

|

||||

|

||||

[][44]

|

||||

|

||||

这张幻灯片显示了低级语言描述的 `runtime.Syscall` 函数,它是 `os` 包中所有函数的基础。

|

||||

|

||||

只要你的代码调用操作系统,就会通过此函数。

|

||||

|

||||

对 `entersyscall` 的调用通知运行时该线程即将阻塞。

|

||||

|

||||

这允许运行时启动一个新线程,该线程将在当前线程被阻塞时为其他 goroutine 提供服务。

|

||||

|

||||

这导致每 Go 进程的操作系统线程相对较少,Go 运行时负责将可运行的 Goroutine 分配给空闲的操作系统线程。

|

||||

|

||||

[][45]

|

||||

|

||||

在上一节中,我讨论了 goroutine 如何减少管理许多(有时是数十万个并发执行线程)的开销。

|

||||

|

||||

Goroutine故事还有另一面,那就是栈管理,它引导我进入我的最后一个话题。

|

||||

|

||||

[][46]

|

||||

|

||||

这是一个进程的内存布局图。我们感兴趣的关键是堆和栈的位置。

|

||||

|

||||

传统上,在进程的地址空间内,堆位于内存的底部,位于程序(代码)的上方并向上增长。

|

||||

|

||||

栈位于虚拟地址空间的顶部,并向下增长。

|

||||

|

||||

[][47]

|

||||

|

||||

因为堆和栈相互覆盖的结果会是灾难性的,操作系统通常会安排在栈和堆之间放置一个不可写内存区域,以确保如果它们发生碰撞,程序将中止。

|

||||

|

||||

这称为保护页,有效地限制了进程的栈大小,通常大约为几兆字节。

|

||||

|

||||

[][48]

|

||||

|

||||

我们已经讨论过线程共享相同的地址空间,因此对于每个线程,它必须有自己的栈。

|

||||

|

||||

由于很难预测特定线程的栈需求,因此为每个线程的栈和保护页面保留了大量内存。

|

||||

|

||||

希望是这些区域永远不被使用,而且防护页永远不会被击中。

|

||||

|

||||

缺点是随着程序中线程数的增加,可用地址空间的数量会减少。

|

||||

|

||||

[][49]

|

||||

|

||||

我们已经看到 Go 运行时将大量的 goroutine 调度到少量线程上,但那些 goroutines 的栈需求呢?

|

||||

|

||||

Go 编译器不使用保护页,而是在每个函数调用时插入一个检查,以检查是否有足够的栈来运行该函数。如果没有,运行时可以分配更多的栈空间。

|

||||

|

||||

由于这种检查,goroutines 初始栈可以做得更小,这反过来允许 Go 程序员将 goroutines 视为廉价资源。

|

||||

|

||||

[][50]

|

||||

|

||||

这是一张显示了 Go 1.2 如何管理栈的幻灯片。

|

||||

|

||||

当 `G` 调用 `H` 时,没有足够的空间让 `H` 运行,所以运行时从堆中分配一个新的栈帧,然后在新的栈段上运行 `H`。当 `H` 返回时,栈区域返回到堆,然后返回到 `G`。

|

||||

|

||||

[][51]

|

||||

|

||||

这种管理栈的方法通常很好用,但对于某些类型的代码,通常是递归代码,它可能导致程序的内部循环跨越这些栈边界之一。

|

||||

|

||||

例如,在程序的内部循环中,函数 `G` 可以在循环中多次调用 `H`,

|

||||

|

||||

每次都会导致栈拆分。 这被称为 <ruby>热分裂<rt>Hot Split</rt></ruby> 问题。

|

||||

|

||||

[][52]

|

||||

|

||||

为了解决热分裂问题,Go 1.3 采用了一种新的栈管理方法。

|

||||

|

||||

如果 goroutine 的栈太小,则不会添加和删除其他栈段,而是分配新的更大的栈。

|

||||

|

||||

旧栈的内容被复制到新栈,然后 goroutine 使用新的更大的栈继续运行。

|

||||

|

||||

在第一次调用 `H` 之后,栈将足够大,对可用栈空间的检查将始终成功。

|

||||

|

||||

这解决了热分裂问题。

|

||||

|

||||

[][53]

|

||||

|

||||

值,内联,逃逸分析,Goroutines 和分段/复制栈。

|

||||

|

||||

这些是我今天选择谈论的五个特性,但它们绝不是使 Go 成为快速的语言的唯一因素,就像人们引用他们学习 Go 的理由的三个原因一样。

|

||||

|

||||

这五个特性一样强大,它们不是孤立存在的。

|

||||

|

||||

例如,运行时将 goroutine 复用到线程上的方式在没有可扩展栈的情况下几乎没有效率。

|

||||

|

||||

内联通过将较小的函数组合成较大的函数来降低栈大小检查的成本。

|

||||

|

||||

逃逸分析通过自动将从实例从堆移动到栈来减少垃圾回收器的压力。

|

||||

|

||||

逃逸分析还提供了更好的 <ruby>缓存局部性<rt>Cache Locality</rt></ruby>。

|

||||

|

||||

如果没有可增长的栈,逃逸分析可能会对栈施加太大的压力。

|

||||

|

||||

[][54]

|

||||

|

||||

* 感谢 Gocon 主办方允许我今天发言

|

||||

* twitter / web / email details

|

||||

* 感谢 @offbymany,@billkennedy_go 和 Minux 在准备这个演讲的过程中所提供的帮助。

|

||||

|

||||

### 相关文章:

|

||||

|

||||

1. [听我在 OSCON 上关于 Go 性能的演讲][1]

|

||||

|

||||

2. [为什么 Goroutine 的栈是无限大的?][2]

|

||||

|

||||

3. [Go 的运行时环境变量的旋风之旅][3]

|

||||

|

||||

4. [没有事件循环的性能][4]

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

作者简介:

|

||||

|

||||

David 是来自澳大利亚悉尼的程序员和作者。

|

||||

|

||||

自 2011 年 2 月起成为 Go 的 contributor,自 2012 年 4 月起成为 committer。

|

||||

|

||||

联系信息

|

||||

|

||||

* dave@cheney.net

|

||||

* twitter: @davecheney

|

||||

|

||||

----------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://dave.cheney.net/2014/06/07/five-things-that-make-go-fast

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Dave Cheney ][a]

|

||||

译者:[houbaron](https://github.com/houbaron)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:https://dave.cheney.net/

|

||||

[1]:https://dave.cheney.net/2015/05/31/hear-me-speak-about-go-performance-at-oscon

|

||||

[2]:https://dave.cheney.net/2013/06/02/why-is-a-goroutines-stack-infinite

|

||||

[3]:https://dave.cheney.net/2015/11/29/a-whirlwind-tour-of-gos-runtime-environment-variables

|

||||

[4]:https://dave.cheney.net/2015/08/08/performance-without-the-event-loop

|

||||

[5]:http://mindchunk.blogspot.com.au/2014/06/remixing-with-deck.html

|

||||

[6]:http://ymotongpoo.hatenablog.com/entry/2014/06/01/124350

|

||||

[7]:http://www.goinggo.net/

|

||||

[8]:https://twitter.com/offbymany

|

||||

[9]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-1.jpg

|

||||

[10]:https://dave.cheney.net/2014/06/07/five-things-that-make-go-fast/gocon-2014-2

|

||||

[11]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-3.jpg

|

||||

[12]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-4.jpg

|

||||

[13]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-5.jpg

|

||||

[14]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-6.jpg

|

||||

[15]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-7.jpg

|

||||

[16]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-8.jpg

|

||||

[17]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-9.jpg

|

||||

[18]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-10.jpg

|

||||

[19]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-11.jpg

|

||||

[20]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-12.jpg

|

||||

[21]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-13.jpg

|

||||

[22]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-14.jpg

|

||||

[23]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-15.jpg

|

||||

[24]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-16.jpg

|

||||

[25]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-17.jpg

|

||||

[26]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-18.jpg

|

||||

[27]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-19.jpg

|

||||

[28]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-20.jpg

|

||||

[29]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-21.jpg

|

||||

[30]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-22.jpg

|

||||

[31]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-23.jpg

|

||||

[32]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-24.jpg

|

||||

[33]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-25.jpg

|

||||

[34]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-26.jpg

|

||||

[35]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-27.jpg

|

||||

[36]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-28.jpg

|

||||

[37]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-30.jpg

|

||||

[38]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-29.jpg

|

||||

[39]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-31.jpg

|

||||

[40]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-32.jpg

|

||||

[41]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-33.jpg

|

||||

[42]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-34.jpg

|

||||

[43]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-35.jpg

|

||||

[44]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-36.jpg

|

||||

[45]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-37.jpg

|

||||

[46]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-39.jpg

|

||||

[47]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-40.jpg

|

||||

[48]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-41.jpg

|

||||

[49]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-42.jpg

|

||||

[50]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-43.jpg

|

||||

[51]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-44.jpg

|

||||

[52]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-45.jpg

|

||||

[53]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-46.jpg

|

||||

[54]:https://dave.cheney.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Gocon-2014-47.jpg

|

||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user