mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-03-27 02:30:10 +08:00

Translated by qhwdw

This commit is contained in:

parent

93db9973e4

commit

6b1922cbd2

@ -1,91 +0,0 @@

|

||||

Translating by qhwdw [What does an idle CPU do?][1]

|

||||

============================================================

|

||||

|

||||

In the [last post][2] I said the fundamental axiom of OS behavior is that at any given time, exactly one and only one task is active on a CPU. But if there's absolutely nothing to do, then what?

|

||||

|

||||

It turns out that this situation is extremely common, and for most personal computers it's actually the norm: an ocean of sleeping processes, all waiting on some condition to wake up, while nearly 100% of CPU time is going into the mythical "idle task." In fact, if the CPU is consistently busy for a normal user, it's often a misconfiguration, bug, or malware.

|

||||

|

||||

Since we can't violate our axiom, some task needs to be active on a CPU. First because it's good design: it would be unwise to spread special cases all over the kernel checking whether there is in fact an active task. A design is far better when there are no exceptions. Whenever you write an if statement, Nyan Cat cries. And second, we need to do something with all those idle CPUs, lest they get spunky and, you know, create Skynet.

|

||||

|

||||

So to keep design consistency and be one step ahead of the devil, OS developers create an idle task that gets scheduled to run when there's no other work. We have seen in the Linux [boot process][3] that the idle task is process 0, a direct descendent of the very first instruction that runs when a computer is first turned on. It is initialized in [rest_init][4], where [init_idle_bootup_task][5] initializes the idle scheduling class.

|

||||

|

||||

Briefly, Linux supports different scheduling classes for things like real-time processes, regular user processes, and so on. When it's time to choose a process to become the active task, these classes are queried in order of priority. That way, the nuclear reactor control code always gets to run before the web browser. Often, though, these classes return NULL, meaning they don't have a suitable process to run - they're all sleeping. But the idle scheduling class, which runs last, never fails: it always returns the idle task.

|

||||

|

||||

That's all good, but let's get down to just what exactly this idle task is doing. So here is [cpu_idle_loop][6], courtesy of open source:

|

||||

|

||||

cpu_idle_loop

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

while (1) {

|

||||

while(!need_resched()) {

|

||||

cpuidle_idle_call();

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

/*

|

||||

[Note: Switch to a different task. We will return to this loop when the idle task is again selected to run.]

|

||||

*/

|

||||

schedule_preempt_disabled();

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

I've omitted many details, and we'll look at task switching closely later on, but if you read the code you'll get the gist of it: as long as there's no need to reschedule, meaning change the active task, stay idle. Measured in elapsed time, this loop and its cousins in other OSes are probably the most executed pieces of code in computing history. For Intel processors, staying idle traditionally meant running the [halt][7] instruction:

|

||||

|

||||

native_halt

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

static inline void native_halt(void)

|

||||

{

|

||||

asm volatile("hlt": : :"memory");

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

hlt stops code execution in the processor and puts it in a halted state. It's weird to think that across the world millions and millions of Intel-like CPUs are spending the majority of their time halted, even while they're powered up. It's also not terribly efficient, energy wise, which led chip makers to develop deeper sleep states for processors, which trade off less power consumption for longer wake-up latency. The kernel's [cpuidle subsystem][8] is responsible for taking advantage of these power-saving modes.

|

||||

|

||||

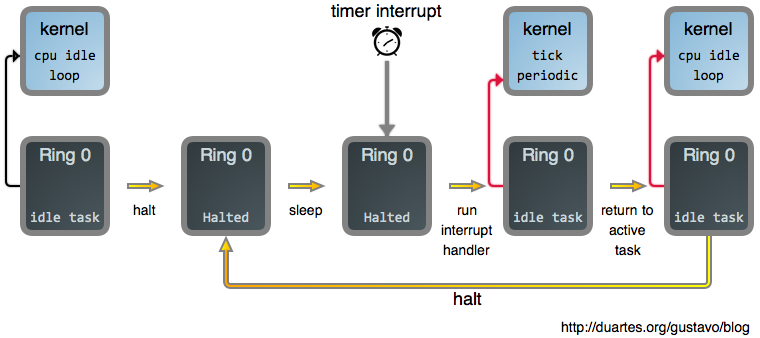

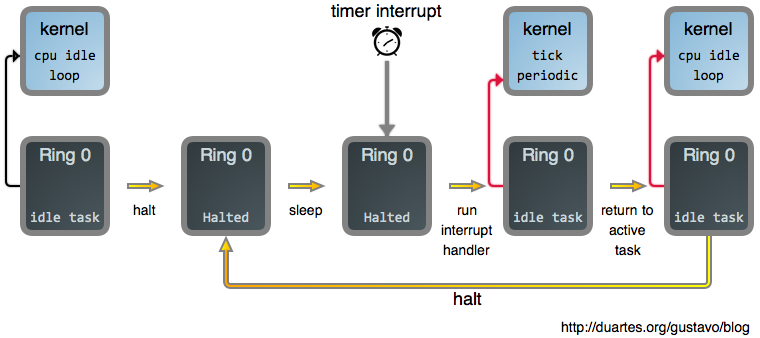

Now once we tell the CPU to halt, or sleep, we need to somehow bring it back to life. If you've read the [last post][9], you might suspect interrupts are involved, and indeed they are. Interrupts spur the CPU out of its halted state and back into action. So putting this all together, here's what your system mostly does as you read a fully rendered web page:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Other interrupts besides the timer interrupt also get the processor moving again. That's what happens if you click on a web page, for example: your mouse issues an interrupt, its driver processes it, and suddenly a process is runnable because it has fresh input. At that point need_resched() returns true, and the idle task is booted out in favor of your browser.

|

||||

|

||||

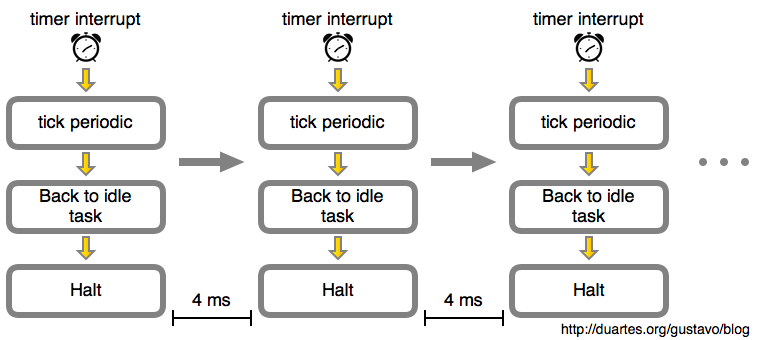

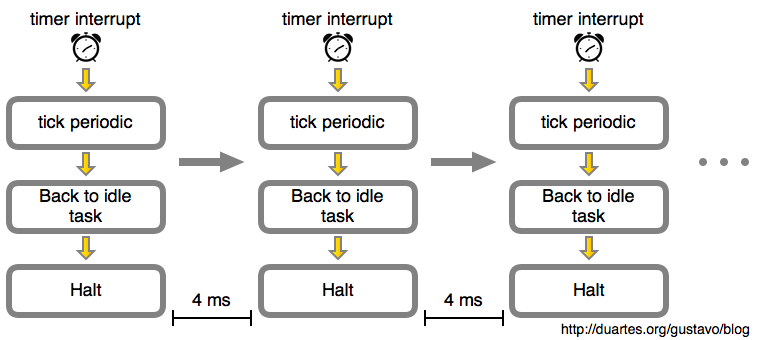

But let's stick to idleness in this post. Here's the idle loop over time:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

In this example the timer interrupt was programmed by the kernel to happen every 4 milliseconds (ms). This is the tick period. That means we get 250 ticks per second, so the tick rate or tick frequency is 250 Hz. That's a typical value for Linux running on Intel processors, with 100 Hz being another crowd favorite. This is defined in the CONFIG_HZ option when you build the kernel.

|

||||

|

||||

Now that looks like an awful lot of pointless work for an idle CPU, and it is. Without fresh input from the outside world, the CPU will remain stuck in this hellish nap getting woken up 250 times a second while your laptop battery is drained. If this is running in a virtual machine, we're burning both power and valuable cycles from the host CPU.

|

||||

|

||||

The solution here is to have a [dynamic tick][10] so that when the CPU is idle, the timer interrupt is either [deactivated or reprogrammed][11] to happen at a point where the kernel knows there will be work to do (for example, a process might have a timer expiring in 5 seconds, so we must not sleep past that). This is also called tickless mode.

|

||||

|

||||

Finally, suppose you have one active process in a system, for example a long-running CPU-intensive task. That's nearly identical to an idle system: these diagrams remain about the same, just substitute the one process for the idle task and the pictures are accurate. In that case it's still pointless to interrupt the task every 4 ms for no good reason: it's merely OS jitter slowing your work ever so slightly. Linux can also stop the fixed-rate tick in this one-process scenario, in what's called [adaptive-tick][12] mode. Eventually, a fixed-rate tick may be gone [altogether][13].

|

||||

|

||||

That's enough idleness for one post. The kernel's idle behavior is an important part of the OS puzzle, and it's very similar to other situations we'll see, so this helps us build the picture of a running kernel. More next week, [RSS][14] and [Twitter][15].

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via:https://manybutfinite.com/post/what-does-an-idle-cpu-do/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Gustavo Duarte][a]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/about/

|

||||

[1]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/what-does-an-idle-cpu-do/

|

||||

[2]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/when-does-your-os-run

|

||||

[3]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/kernel-boot-process

|

||||

[4]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/init/main.c#L393

|

||||

[5]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/kernel/sched/core.c#L4538

|

||||

[6]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/kernel/sched/idle.c#L183

|

||||

[7]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/arch/x86/include/asm/irqflags.h#L52

|

||||

[8]:http://lwn.net/Articles/384146/

|

||||

[9]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/when-does-your-os-run

|

||||

[10]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/Documentation/timers/NO_HZ.txt#L17

|

||||

[11]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/Documentation/timers/highres.txt#L215

|

||||

[12]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/Documentation/timers/NO_HZ.txt#L100

|

||||

[13]:http://lwn.net/Articles/549580/

|

||||

[14]:https://manybutfinite.com/feed.xml

|

||||

[15]:http://twitter.com/manybutfinite

|

||||

91

translated/tech/20141029 What does an idle CPU do.md

Normal file

91

translated/tech/20141029 What does an idle CPU do.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,91 @@

|

||||

[当 CPU 空闲时它都在做什么?][1]

|

||||

============================================================

|

||||

|

||||

在 [上篇文章中][2] 我说了操作系统行为的基本原理是,在任何一个给定的时刻,在一个 CPU 上有且只有一个任务是活动的。但是,如果 CPU 无事可做的时候,又会是什么样的呢?

|

||||

|

||||

事实证明,这种情况是非常普遍的,对于绝大多数的个人电脑来说,这确实是一种常态:大量的睡眠进程,它们都在等待某种情况下被唤醒,差不多在 100% 的 CPU 时间中,它们都处于虚构的“空闲任务”中。事实上,如果一个普通用户的 CPU 处于持续的繁忙中,它可能意味着有一个错误、bug、或者运行了恶意软件。

|

||||

|

||||

因为我们不能违反我们的原理,一些任务需要在一个 CPU 上激活。首先是因为,这是一个良好的设计:持续很长时间去遍历内核,检查是否有一个活动任务,这种特殊情况是不明智的做法。最好的设计是没有任何例外的情况。无论何时,你写一个 `if` 语句,Nyan 猫就会叫。其次,我们需要使用空闲的 CPU 去做一些事情,让它们充满活力,并且,你懂得,创建天网卫星计划。

|

||||

|

||||

因此,保持这种设计的连续性,并领先于恶魔(devil)一步,操作系统开发者创建了一个空闲任务,当没有其它任务可做时就调度它去运行。我们可以在 Linux 的 [引导进程][3] 中看到,这个空闲任务就是进程 0,它是由计算机打开电源时运行的第一个指令直接派生出来的。它在 [rest_init][4] 中初始化,在 [init_idle_bootup_task][5] 中初始化空闲调度类。

|

||||

|

||||

简而言之,Linux 支持像实时进程、普通用户进程、等等的不同调度类。当选择一个进程变成活动任务时,这些类是被优先询问的。通过这种方式,核反应堆的控制代码总是优先于 web 浏览器运行。尽管在通常情况下,这些类返回 `NULL`,意味着它们没有合适的任务需要去运行 —— 它们总是处于睡眠状态。但是空闲调度类,它是持续运行的,从不会失败:它总是返回空闲任务。

|

||||

|

||||

好吧,我们来看一下这个空闲任务到底做了些什么。下面是 [cpu_idle_loop][6],感谢开源能让我们看到它的代码:

|

||||

|

||||

cpu_idle_loop

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

while (1) {

|

||||

while(!need_resched()) {

|

||||

cpuidle_idle_call();

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

/*

|

||||

[Note: Switch to a different task. We will return to this loop when the idle task is again selected to run.]

|

||||

*/

|

||||

schedule_preempt_disabled();

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

我省略了很多的细节,稍后我们将去了解任务切换,但是,如果你阅读了源代码,你就会找到它的要点:由于这里不需要重新调度 —— 改变活动任务,它一直处于空闲状态。以经过的时间来计算,这个循环和操作系统中它的“堂兄弟们”相比,在计算的历史上它是运行的最多的代码片段。对于 Intel 处理器来说,处于空闲状态意味着运行着一个 [halt][7] 指令:

|

||||

|

||||

native_halt

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

static inline void native_halt(void)

|

||||

{

|

||||

asm volatile("hlt": : :"memory");

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

`halt` 指令停止处理器中运行的代码,并将它置于 `halt` 的状态。奇怪的是,全世界各地数以百万计的像 Intel 这样的 CPU 们花费大量的时间让它们处于 `halt` 的状态,直到它们被激活。这并不是高效、节能的做法,这促使芯片制造商们去开发处理器的深度睡眠状态,它意味着更少的功耗和更长的唤醒延迟。内核的 [cpuidle 子系统][8] 是这些节能模式能够产生好处的原因。

|

||||

|

||||

现在,一旦我们告诉 CPU 去 `halt` 或者睡眠之后,我们需要以某种方式去将它t重新带回(back to life)。如果你读过 [上篇文章][9],(译者注:指的是《你的操作系统什么时候运行?》) 你可能会猜到中断会参与其中,而事实确实如此。中断促使 CPU 离开 `halt` 状态返回到激活状态。因此,将这些拼到一起,下图是当你阅读一个完全呈现的 web 网页时,你的系统主要做的事情:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

除定时器中断外的其它中断也会使处理器再次发生变化。如果你再次点击一个 web 页面就会产生这种变化,例如:你的鼠标发出一个中断,它会导致系统去处理它,并且使处理器因为它产生了一个新的输入而突然地可运行。在那个时刻, `need_resched()` 返回 `true`,然后空闲任务因你的浏览器而被踢出终止运行。

|

||||

|

||||

如果我们阅读这篇文章,而不做任何事情。那么随着时间的推移,这个空闲循环就像下图一样:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

在这个示例中,由内核计划的定时器中断会每 4 毫秒发生一次。这就是滴答周期。也就是说每秒钟将有 250 个滴答,因此,这个滴答速率或者频率是 250 Hz。这是运行在 Intel 处理器上的 Linux 的典型值,而很多人喜欢使用 100 Hz。这是由你构建内核时在 `CONFIG_HZ` 选项中定义的。

|

||||

|

||||

对于一个空闲 CPU 来说,它看起来似乎是个无意义的工作。如果外部世界没有新的输入,在你的笔记本电脑的电池耗尽之前,CPU 将始终处于这种每秒钟被唤醒 250 次的地狱般折磨的小憩中。如果它运行在一个虚拟机中,那我们正在消耗着宿主机 CPU 的性能和宝贵的时钟周期。

|

||||

|

||||

在这里的解决方案是拥有一个 [动态滴答][10] ,因此,当 CPU 处于空闲状态时,定时器中断要么被 [暂停要么被重计划][11],直到内核知道将有事情要做时(例如,一个进程的定时器可能要在 5 秒内过期,因此,我们不能再继续睡眠了),定时器中断才会重新发出。这也被称为无滴答模式。

|

||||

|

||||

最后,假设在一个系统中你有一个活动进程,例如,一个长周期运行的 CPU 密集型任务。那样几乎就和一个空闲系统是相同的:这些示意图仍然是相同的,只是将空闲任务替换为这个进程,并且描述也是准确的。在那种情况下,每 4 毫秒去中断一次任务仍然是无意义的:它只是操作系统的抖动,甚至会使你的工作变得更慢而已。Linux 也可以在这种单一进程的场景中停止这种固定速率的滴答,这被称为 [adaptive-tick][12] 模式。最终,这种固定速率的滴答可能会 [完全消失][13]。

|

||||

|

||||

对于阅读一篇文章来说,CPU 基本是无事可做的。内核的这种空闲行为是操作系统难题的一个重要部分,并且它与我们看到的其它情况非常相似,因此,这将帮助我们构建一个运行中的内核的蓝图。更多的内容将发布在下周的 [RSS][14] 和 [Twitter][15] 上。

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via:https://manybutfinite.com/post/what-does-an-idle-cpu-do/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Gustavo Duarte][a]

|

||||

译者:[qhwdw](https://github.com/qhwdw)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/about/

|

||||

[1]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/what-does-an-idle-cpu-do/

|

||||

[2]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/when-does-your-os-run

|

||||

[3]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/kernel-boot-process

|

||||

[4]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/init/main.c#L393

|

||||

[5]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/kernel/sched/core.c#L4538

|

||||

[6]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/kernel/sched/idle.c#L183

|

||||

[7]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/arch/x86/include/asm/irqflags.h#L52

|

||||

[8]:http://lwn.net/Articles/384146/

|

||||

[9]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/when-does-your-os-run

|

||||

[10]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/Documentation/timers/NO_HZ.txt#L17

|

||||

[11]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/Documentation/timers/highres.txt#L215

|

||||

[12]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.17/Documentation/timers/NO_HZ.txt#L100

|

||||

[13]:http://lwn.net/Articles/549580/

|

||||

[14]:https://manybutfinite.com/feed.xml

|

||||

[15]:http://twitter.com/manybutfinite

|

||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user