mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-03-24 02:20:09 +08:00

Merge pull request #8701 from FSSlc/master

[Translated] 20170925 Advanced image viewing tricks with ImageMagick.md 很好。

This commit is contained in:

commit

6ac074d18f

@ -1,115 +0,0 @@

|

||||

FSSlc translating

|

||||

|

||||

Advanced image viewing tricks with ImageMagick

|

||||

======

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

In my [introduction to ImageMagick][1], I showed how to use the application's menus to edit and add effects to your images. In this follow-up, I'll show additional ways to use this open source image editor to view your images.

|

||||

|

||||

### Another effect

|

||||

|

||||

Before diving into advanced image viewing with ImageMagick, I want to share another interesting, yet simple, effect using the **convert** command, which I discussed in detail in my previous article. This involves the

|

||||

**-edge** option, then **negate** :

|

||||

```

|

||||

convert DSC_0027.JPG -edge 3 -negate edge3+negate.jpg

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

![Using the edge and negate options on an image.][3]

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Before and after example of using the edge and negate options on an image.

|

||||

|

||||

There are a number of things I like about the edited image--the appearance of the sea, the background and foreground vegetation, but especially the sun and its reflection, and also the sky.

|

||||

|

||||

### Using display to view a series of images

|

||||

|

||||

If you're a command-line user like I am, you know that the shell provides a lot of flexibility and shortcuts for complex tasks. Here I'll show one example: the way ImageMagick's **display** command can overcome a problem I've had reviewing images I import with the [Shotwell][4] image manager for the GNOME desktop.

|

||||

|

||||

Shotwell creates a nice directory structure that uses each image's [Exif][5] data to store imported images based on the date they were taken or created. You end up with a top directory for the year, subdirectories for each month (01, 02, 03, and so on), followed by another level of subdirectories for each day of the month. I like this structure, because finding an image or set of images based on when they were taken is easy.

|

||||

|

||||

This structure is not so great, however, when I want to review all my images for the last several months or even the whole year. With a typical image viewer, this involves a lot of jumping up and down the directory structure, but ImageMagick's **display** command makes it simple. For example, imagine that I want to look at all my pictures for this year. If I enter **display** on the command line like this:

|

||||

```

|

||||

display -resize 35 % 2017 /*/*/*.JPG

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

I can march through the year, month by month, day by day.

|

||||

|

||||

Now imagine I'm looking for an image, but I can't remember whether I took it in the first half of 2016 or the first half of 2017. This command:

|

||||

```

|

||||

display -resize 35% 201[6-7]/0[1-6]/*/*.JPG

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

restricts the images shown to January through June of 2016 and 2017.

|

||||

|

||||

### Using montage to view thumbnails of images

|

||||

|

||||

Now say I'm looking for an image that I want to edit. One problem is that **display** shows each image's filename, but not its place in the directory structure, so it's not obvious where I can find that image. Also, when I (sporadically) download images from my camera, I clear them from the camera's storage, so the filenames restart at **DSC_0001.jpg** at unpredictable times. Finally, it can take a lot of time to go through 12 months of images when I use **display** to show an entire year.

|

||||

|

||||

This is where the **montage** command, which puts thumbnail versions of a series of images into a single image, can be very useful. For example:

|

||||

```

|

||||

montage -label %d/%f -title 2017 -tile 5x -resize 10% -geometry +4+4 2017/0[1-4]/*/*.JPG 2017JanApr.jpg

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

From left to right, this command starts by specifying a label for each image that consists of the filename ( **%f** ) and its directory ( **%d** ) structure, separated with **/**. Next, the command specifies the main directory as the title, then instructs the montage to tile the images in five columns, with each image resized to 10% (which fits my monitor's screen easily). The geometry setting puts whitespace around each image. Finally, it specifies which images to include in the montage, and an appropriate filename to save the montage ( **2017JanApr.jpg** ). So now the image **2017JanApr.jpg** becomes a reference I can use over and over when I want to view all my images from this time period.

|

||||

|

||||

### Managing memory

|

||||

|

||||

You might wonder why I specified just a four-month period (January to April) for this montage. Here is where you need to be a bit careful, because **montage** can consume a lot of memory. My camera creates image files that are about 2.5MB each, and I have found that my system's memory can pretty easily handle 60 images or so. When I get to around 80, my computer freezes when other programs, such as Firefox and Thunderbird, are running the background. This seems to relate to memory usage, which goes up to 80% or more of available RAM for **montage**. (You can check this by running **top** while you do this procedure.) If I shut down all other programs, I can manage 80 images before my system freezes.

|

||||

|

||||

Here's how you can get some sense of how many files you're dealing with before running the **montage** command:

|

||||

```

|

||||

ls 2017/0[1-4/*/*.JPG > filelist; wc -l filelist

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The command **ls** generates a list of the files in our search and saves it to the arbitrarily named filelist. Then, the **wc** command with the **-l** option reports how many lines are in the file, in other words, how many files **ls** found. Here's my output:

|

||||

```

|

||||

163 filelist

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Oops! There are 163 images taken from January through April, and creating a montage of all of them would almost certainly freeze up my system. I need to trim down the list a bit, maybe just to March or even earlier. But what if I took a lot of pictures from April 20 to 30, and I think that's a big part of my problem. Here's how the shell can help us figure this out:

|

||||

```

|

||||

ls 2017/0[1-3]/*/*.JPG > filelist; ls 2017/04/0[1-9]/*.JPG >> filelist; ls 2017/04/1[0-9]/*.JPG >> filelist; wc -l filelist

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This is a series of four commands all on one line, separated by semicolons. The first command specifies the number of images taken from January to March; the second adds April 1 through 9 using the **> >** append operator; the third appends April 10 through 19. The fourth command, **wc -l** , reports:

|

||||

```

|

||||

81 filelist

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

I know 81 files should be doable if I shut down my other applications.

|

||||

|

||||

Managing this with the **montage** command is easy, since we're just transposing what we did above:

|

||||

```

|

||||

montage -label %d/%f -title 2017 -tile 5x -resize 10% -geometry +4+4 2017/0[1-3]/*/*.JPG 2017/04/0[1-9]/*.JPG 2017/04/1[0-9]/*.JPG 2017Jan01Apr19.jpg

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The last filename in the **montage** command will be the output; everything before that is input and is read from left to right. This took just under three minutes to run and resulted in an image about 2.5MB in size, but my system was sluggish for a bit afterward.

|

||||

|

||||

### Displaying the montage

|

||||

|

||||

When you first view a large montage using the **display** command, you may see that the montage's width is OK, but the image is squished vertically to fit the screen. Don't worry; just left-click the image and select **View > Original Size**. Click again to hide the menu.

|

||||

|

||||

I hope this has been helpful in showing you new ways to view your images. In my next article, I'll discuss more complex image manipulation.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

### About The Author

|

||||

Greg Pittman;Greg Is A Retired Neurologist In Louisville;Kentucky;With A Long-Standing Interest In Computers;Programming;Beginning With Fortran Iv In The When Linux;Open Source Software Came Along;It Kindled A Commitment To Learning More;Eventually Contributing. He Is A Member Of The Scribus Team.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://opensource.com/article/17/9/imagemagick-viewing-images

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Greg Pittman][a]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:https://opensource.com/users/greg-p

|

||||

[1]:https://opensource.com/article/17/8/imagemagick

|

||||

[2]:/file/370946

|

||||

[3]:https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/u128651/edge3negate.jpg (Using the edge and negate options on an image.)

|

||||

[4]:https://wiki.gnome.org/Apps/Shotwell

|

||||

[5]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exif

|

||||

@ -1,47 +1,48 @@

|

||||

#[递归:梦中梦][1]

|

||||

递归是很神奇的,但是在大多数的编程类书藉中对递归讲解的并不好。它们只是给你展示一个递归阶乘的实现,然后警告你递归运行的很慢,并且还有可能因为栈缓冲区溢出而崩溃。“你可以将头伸进微波炉中去烘干你的头发,但是需要警惕颅内高压以及让你的头发生爆炸,或者你可以使用毛巾来擦干头发。”这就是人们不愿意使用递归的原因。这是很糟糕的,因为在算法中,递归是最强大的。

|

||||

[递归:梦中梦][1]

|

||||

======

|

||||

|

||||

**递归**是很神奇的,但是在大多数的编程类书藉中对递归讲解的并不好。它们只是给你展示一个递归阶乘的实现,然后警告你递归运行的很慢,并且还有可能因为栈缓冲区溢出而崩溃。“你可以将头伸进微波炉中去烘干你的头发,但是需要警惕颅内高压以及让你的头发生爆炸,或者你可以使用毛巾来擦干头发。”难怪人们不愿意使用递归。但这种建议是很糟糕的,因为在算法中,递归是一个非常强大的观点。

|

||||

|

||||

我们来看一下这个经典的递归阶乘:

|

||||

|

||||

递归阶乘 - factorial.c

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

#include <stdio.h>

|

||||

|

||||

int factorial(int n)

|

||||

{

|

||||

int previous = 0xdeadbeef;

|

||||

|

||||

if (n == 0 || n == 1) {

|

||||

return 1;

|

||||

}

|

||||

int previous = 0xdeadbeef;

|

||||

|

||||

if (n == 0 || n == 1) {

|

||||

return 1;

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

previous = factorial(n-1);

|

||||

return n * previous;

|

||||

previous = factorial(n-1);

|

||||

return n * previous;

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

int main(int argc)

|

||||

{

|

||||

int answer = factorial(5);

|

||||

printf("%d\n", answer);

|

||||

int answer = factorial(5);

|

||||

printf("%d\n", answer);

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

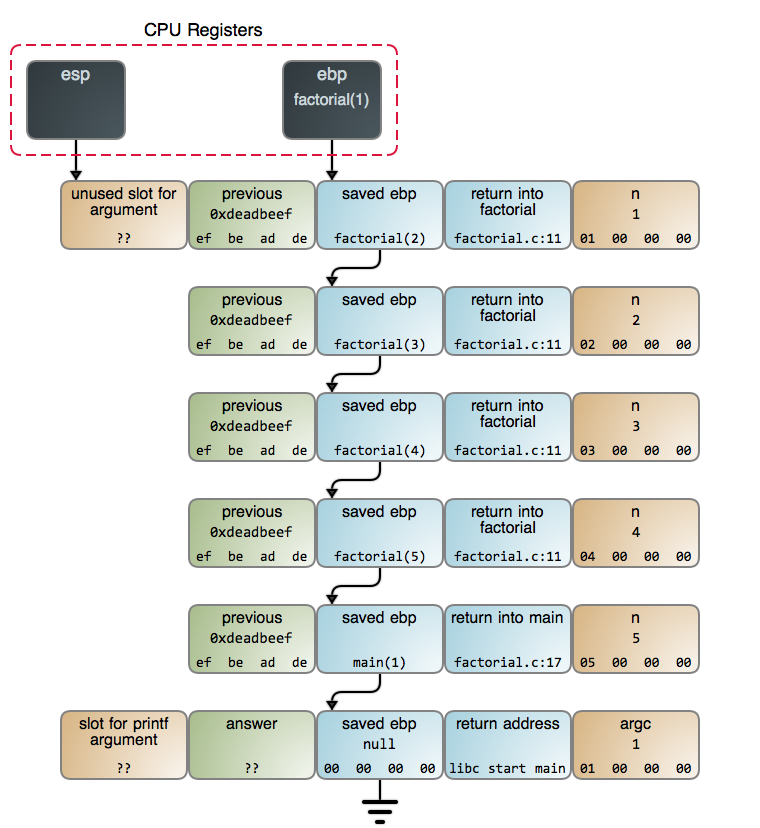

函数的目的是调用它自己,这在一开始是让人很难理解的。为了解具体的内容,当调用 `factorial(5)` 并且达到 `n == 1` 时,[在栈上][3] 究竟发生了什么?

|

||||

函数调用自身的这个观点在一开始是让人很难理解的。为了让这个过程更形象具体,下图展示的是当调用 `factorial(5)` 并且达到 `n == 1`这行代码 时,[栈上][3] 端点的情况:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

每次调用 `factorial` 都生成一个新的 [栈帧][4]。这些栈帧的创建和 [销毁][5] 是递归慢于迭代的原因。在调用返回之前,累积的这些栈帧可能会耗尽栈空间,进而使你的程序崩溃。

|

||||

每次调用 `factorial` 都生成一个新的 [栈帧][4]。这些栈帧的创建和 [销毁][5] 是使得递归版本的阶乘慢于其相应的迭代版本的原因。在调用返回之前,累积的这些栈帧可能会耗尽栈空间,进而使你的程序崩溃。

|

||||

|

||||

而这些担心经常是存在于理论上的。例如,对于每个 `factorial` 的栈帧取 16 字节(这可能取决于栈排列以及其它因素)。如果在你的电脑上运行着现代的 x86 的 Linux 内核,一般情况下你拥有 8 GB 的栈空间,因此,`factorial` 最多可以被运行 ~512,000 次。这是一个 [巨大无比的结果][6],它相当于 8,971,833 比特,因此,栈空间根本就不是什么问题:一个极小的整数 - 甚至是一个 64 位的整数 - 在我们的栈空间被耗尽之前就早已经溢出了成千上万次了。

|

||||

而这些担心经常是存在于理论上的。例如,对于每个 `factorial` 的栈帧占用 16 字节(这可能取决于栈排列以及其它因素)。如果在你的电脑上运行着现代的 x86 的 Linux 内核,一般情况下你拥有 8 GB 的栈空间,因此,`factorial` 程序中的 `n` 最多可以达到 512,000 左右。这是一个 [巨大无比的结果][6],它将花费 8,971,833 比特来表示这个结果,因此,栈空间根本就不是什么问题:一个极小的整数 - 甚至是一个 64 位的整数 - 在我们的栈空间被耗尽之前就早已经溢出了成千上万次了。

|

||||

|

||||

过一会儿我们再去看 CPU 的使用,现在,我们先从比特和字节回退一步,把递归看作一种通用技术。我们的阶乘算法总结为将整数 N、N-1、 … 1 推入到一个栈,然后将它们按相反的顺序相乘。实际上我们使用了程序调用栈来实现这一点,这是它的细节:我们在堆上分配一个栈并使用它。虽然调用栈具有特殊的特性,但是,你只是把它用作一种另外的数据结构。我希望示意图可以让你明白这一点。

|

||||

过一会儿我们再去看 CPU 的使用,现在,我们先从比特和字节回退一步,把递归看作一种通用技术。我们的阶乘算法可归结为:将整数 N、N-1、 … 1 推入到一个栈,然后将它们按相反的顺序相乘。实际上我们使用了程序调用栈来实现这一点,这是它的细节:我们在堆上分配一个栈并使用它。虽然调用栈具有特殊的特性,但是它也只是额外的一种数据结构,你可以随意处置。我希望示意图可以让你明白这一点。

|

||||

|

||||

当你看到栈调用作为一种数据结构使用,有些事情将变得更加清晰明了:将那些整数堆积起来,然后再将它们相乘,这并不是一个好的想法。那是一种有缺陷的实现:就像你拿螺丝刀去钉钉子一样。相对更合理的是使用一个迭代过程去计算阶乘。

|

||||

当你将栈调用视为一种数据结构,有些事情将变得更加清晰明了:将那些整数堆积起来,然后再将它们相乘,这并不是一个好的想法。那是一种有缺陷的实现:就像你拿螺丝刀去钉钉子一样。相对更合理的是使用一个迭代过程去计算阶乘。

|

||||

|

||||

但是,螺丝钉太多了,我们只能挑一个。有一个经典的面试题,在迷宫里有一只老鼠,你必须帮助这只老鼠找到一个奶酪。假设老鼠能够在迷宫中向左或者向右转弯。你该怎么去建模来解决这个问题?

|

||||

|

||||

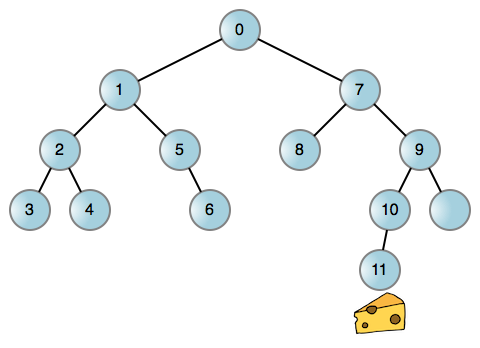

就像现实生活中的很多问题一样,你可以将这个老鼠找奶酪的问题简化为一个图,一个二叉树的每个结点代表在迷宫中的一个位置。然后你可以让老鼠在任何可能的地方都左转,而当它进入一个死胡同时,再返回来右转。这是一个老鼠行走的 [迷宫示例][7]:

|

||||

就像现实生活中的很多问题一样,你可以将这个老鼠找奶酪的问题简化为一个图,一个二叉树的每个结点代表在迷宫中的一个位置。然后你可以让老鼠在任何可能的地方都左转,而当它进入一个死胡同时,再回溯回去,再右转。这是一个老鼠行走的 [迷宫示例][7]:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@ -55,40 +56,40 @@ int main(int argc)

|

||||

|

||||

int explore(maze_t *node)

|

||||

{

|

||||

int found = 0;

|

||||

int found = 0;

|

||||

|

||||

if (node == NULL)

|

||||

{

|

||||

return 0;

|

||||

}

|

||||

if (node->hasCheese){

|

||||

return 1;// found cheese

|

||||

}

|

||||

if (node == NULL)

|

||||

{

|

||||

return 0;

|

||||

}

|

||||

if (node->hasCheese){

|

||||

return 1;// found cheese

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

found = explore(node->left) || explore(node->right);

|

||||

return found;

|

||||

}

|

||||

found = explore(node->left) || explore(node->right);

|

||||

return found;

|

||||

}

|

||||

|

||||

int main(int argc)

|

||||

{

|

||||

int found = explore(&maze);

|

||||

}

|

||||

int main(int argc)

|

||||

{

|

||||

int found = explore(&maze);

|

||||

}

|

||||

```

|

||||

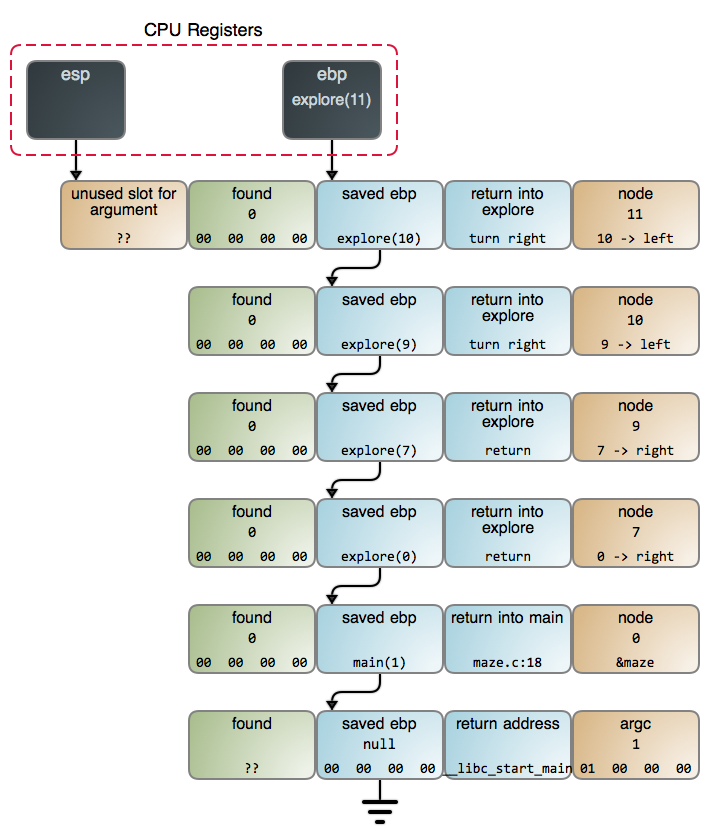

当我们在 `maze.c:13` 中找到奶酪时,栈的情况如下图所示。你也可以在 [GDB 输出][8] 中看到更详细的数据,它是使用 [命令][9] 采集的数据。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

它展示了递归的良好表现,因为这是一个适合使用递归的问题。而且这并不奇怪:当涉及到算法时,递归是一种使用较多的算法,而不是被排除在外的。当进行搜索时、当进行遍历树和其它数据结构时、当进行解析时、当需要排序时:它的用途无处不在。正如众所周知的 pi 或者 e,它们在数学中像“神”一样的存在,因为它们是宇宙万物的基础,而递归也和它们一样:只是它在计算的结构中。

|

||||

它展示了递归的良好表现,因为这是一个适合使用递归的问题。而且这并不奇怪:当涉及到算法时,递归是规则,而不是例外。它出现在如下情景中:当进行搜索时、当进行遍历树和其它数据结构时、当进行解析时、当需要排序时:它无处不在。正如众所周知的 pi 或者 e,它们在数学中像“神”一样的存在,因为它们是宇宙万物的基础,而递归也和它们一样:只是它在计算的结构中。

|

||||

|

||||

Steven Skienna 的优秀著作 [算法设计指南][10] 的精彩之处在于,他通过“战争故事” 作为手段来诠释工作,以此来展示解决现实世界中的问题背后的算法。这是我所知道的拓展你的算法知识的最佳资源。另一个较好的做法是,去读 McCarthy 的 [LISP 上的原创论文][11]。递归在语言中既是它的名字也是它的基本原理。这篇论文既可读又有趣,在工作中能看到大师的作品是件让人兴奋的事情。

|

||||

Steven Skienna 的优秀著作 [算法设计指南][10] 的精彩之处在于,他通过“战争故事” 作为手段来诠释工作,以此来展示解决现实世界中的问题背后的算法。这是我所知道的拓展你的算法知识的最佳资源。另一个读物是 McCarthy 的 [关于 LISP 实现的的原创论文][11]。递归在语言中既是它的名字也是它的基本原理。这篇论文既可读又有趣,在工作中能看到大师的作品是件让人兴奋的事情。

|

||||

|

||||

回到迷宫问题上。虽然它在这里很难离开递归,但是并不意味着必须通过调用栈的方式来实现。你可以使用像 “RRLL” 这样的字符串去跟踪转向,然后,依据这个字符串去决定老鼠下一步的动作。或者你可以分配一些其它的东西来记录奶酪的状态。你仍然是去实现一个递归的过程,但是需要你实现一个自己的数据结构。

|

||||

回到迷宫问题上。虽然它在这里很难离开递归,但是并不意味着必须通过调用栈的方式来实现。你可以使用像 `RRLL` 这样的字符串去跟踪转向,然后,依据这个字符串去决定老鼠下一步的动作。或者你可以分配一些其它的东西来记录追寻奶酪的整个状态。你仍然是去实现一个递归的过程,但是需要你实现一个自己的数据结构。

|

||||

|

||||

那样似乎更复杂一些,因为栈调用更合适。每个栈帧记录的不仅是当前节点,也记录那个节点上的计算状态(在这个案例中,我们是否只让它走左边,或者已经尝试向右)。因此,代码已经变得不重要了。然而,有时候我们因为害怕溢出和期望中的性能而放弃这种优秀的算法。那是很愚蠢的!

|

||||

|

||||

正如我们所见,栈空间是非常大的,在耗尽栈空间之前往往会遇到其它的限制。一方面可以通过检查问题大小来确保它能够被安全地处理。而对 CPU 的担心是由两个广为流传的有问题的示例所导致的:哑阶乘(dumb factorial)和可怕的无记忆的 O(2n) [Fibonacci 递归][12]。它们并不是栈递归算法的正确代表。

|

||||

|

||||

事实上栈操作是非常快的。通常,栈对数据的偏移是非常准确的,它在 [缓存][13] 中是热点,并且是由专门的指令来操作它。同时,使用你自己定义的堆上分配的数据结构的相关开销是很大的。经常能看到人们写的一些比栈调用递归更复杂、性能更差的实现方法。最后,现代的 CPU 的性能都是 [非常好的][14] ,并且一般 CPU 不会是性能瓶颈所在。要注意牺牲简单性与保持性能的关系。[测量][15]。

|

||||

事实上栈操作是非常快的。通常,栈对数据的偏移是非常准确的,它在 [缓存][13] 中是热点,并且是由专门的指令来操作它。同时,使用你自己定义的堆上分配的数据结构的相关开销是很大的。经常能看到人们写的一些比栈调用递归更复杂、性能更差的实现方法。最后,现代的 CPU 的性能都是 [非常好的][14] ,并且一般 CPU 不会是性能瓶颈所在。在考虑牺牲程序的简单性时要特别注意,就像经常考虑程序的性能及性能的[测量][15]那样。

|

||||

|

||||

下一篇文章将是探秘栈系列的最后一篇了,我们将了解尾调用、闭包、以及其它相关概念。然后,我们就该深入我们的老朋友—— Linux 内核了。感谢你的阅读!

|

||||

|

||||

@ -100,7 +101,7 @@ via:https://manybutfinite.com/post/recursion/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Gustavo Duarte][a]

|

||||

译者:[qhwdw](https://github.com/qhwdw)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

校对:[FSSlc](https://github.com/FSSlc)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@ -0,0 +1,108 @@

|

||||

ImageMagick 的一些高级图片查看技巧

|

||||

======

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

图片源于 [Internet Archive Book Images](https://www.flickr.com/photos/internetarchivebookimages/14759826206/in/photolist-ougY7b-owgz5y-otZ9UN-waBxfL-oeEpEf-xgRirT-oeMHfj-wPAvMd-ovZgsb-xhpXhp-x3QSRZ-oeJmKC-ovWeKt-waaNUJ-oeHPN7-wwMsfP-oeJGTK-ovZPKv-waJnTV-xDkxoc-owjyCW-oeRqJh-oew25u-oeFTm4-wLchfu-xtjJFN-oxYznR-oewBRV-owdP7k-owhW3X-oxXxRg-oevDEY-oeFjP1-w7ZB6f-x5ytS8-ow9C7j-xc6zgV-oeCpG1-oewNzY-w896SB-wwE3yA-wGNvCL-owavts-oevodT-xu9Lcr-oxZqZg-x5y4XV-w89d3n-x8h6fi-owbfiq),Opensource.com 修改,[CC BY-SA 4.0](https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/)协议

|

||||

|

||||

在我先前的[ImageMagick 入门:使用命令行来编辑图片](https://linux.cn/article-8851-1.html) 文章中,我展示了如何使用 ImageMagick 的菜单栏进行图片的编辑和变换风格。在这篇续文里,我将向你展示使用这个开源的图像编辑器来查看图片的额外方法。

|

||||

|

||||

### 别样的风格

|

||||

|

||||

在深入 ImageMagick 的高级图片查看技巧之前,我想先分享另一个使用 **convert** 达到的有趣但简单的效果,在上一篇文章中我已经详细地介绍了 **convert** 命令,这个技巧涉及这个命令的 `edge` 和 `negate` 选项:

|

||||

```

|

||||

convert DSC_0027.JPG -edge 3 -negate edge3+negate.jpg

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

![在图片上使用 `edge` 和 `negate` 选项][3]

|

||||

使用`edge` 和 `negate` 选项前后的图片对比

|

||||

|

||||

编辑后的图片让我更加喜爱,具体是因为如下因素:海的外观,作为前景和背景的植被,特别是太阳及其在海上的反射,最后是天空。

|

||||

|

||||

### 使用 `display` 来查看一系列图片

|

||||

|

||||

假如你跟我一样是个命令行用户,你就知道 shell 为复杂任务提供了更多的灵活性和快捷方法。下面我将展示一个例子来佐证这个观点。ImageMagick 的 **display** 命令可以克服我在 GNOME 桌面上使用 [Shotwell][4] 图像管理器导入图片时遇到的问题。

|

||||

|

||||

Shotwell 会根据每张导入图片的 [Exif][5] 数据,创建以图片被生成或者拍摄时的日期为名称的目录结构。最终的效果是最上层的目录以年命名,接着的子目录是以月命名 (01, 02, 03 等等),然后是以每月的日期命名的子目录。我喜欢这种结构,因为当我想根据图片被创建或者拍摄时的日期来查找它们时将会非常方便。

|

||||

|

||||

但这种结构也并不是非常完美的,当我想查看最近几个月或者最近一年的所有图片时就会很麻烦。使用常规的图片查看器,我将不停地在不同层级的目录间跳转,但 ImageMagick 的 **display** 命令可以使得查看更加简单。例如,假如我想查看最近一年的图片,我便可以在命令行中键入下面的 **display** 命令:

|

||||

```

|

||||

display -resize 35% 2017/*/*/*.JPG

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

我可以匹配一年中的每一月和每一天。

|

||||

|

||||

现在假如我想查看某张图片,但我不确定我是在 2016 年的上半年还是在 2017 的上半年拍摄的,那么我便可以使用下面的命令来找到它:

|

||||

```

|

||||

display -resize 35% 201[6-7]/0[1-6]/*/*.JPG

|

||||

```

|

||||

限制查看的图片拍摄于 2016 和 2017 年的一月到六月

|

||||

|

||||

### 使用 `montage` 来查看图片的缩略图

|

||||

|

||||

假如现在我要查找一张我想要编辑的图片,使用 **display** 的一个问题是它只会显示每张图片的文件名,而不显示其在目录结构中的位置,所以想要找到那张图片并不容易。另外,假如我很偶然地在从相机下载图片的过程中将这些图片从相机的内存里面清除了它们,结果使得下次拍摄照片的名称又从 **DSC_0001.jpg** 开始命名,那么当使用 **display** 来展示一整年的图片时,将会在这 12 个月的图片中花费很长的时间来查找它们。

|

||||

|

||||

这时 **montage** 命令便可以派上用场了。它可以将一系列的图片放在一张图片中,这样就会非常有用。例如可以使用下面的命令来完成上面的任务:

|

||||

```

|

||||

montage -label %d/%f -title 2017 -tile 5x -resize 10% -geometry +4+4 2017/0[1-4]/*/*.JPG 2017JanApr.jpg

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

从左到右,这个命令以标签开头,标签的形式是包含文件名( **%f** )和以 **/** 分割的目录( **%d** )结构,接着这个命令以目录的名称(2017)来作为标题,然后将图片排成 5 列,每个图片缩放为 10% (这个参数可以很好地匹配我的屏幕)。`geometry` 的设定将在每张图片的四周留白,最后在接上要处理的对象和一个合适的名称( **2017JanApr.jpg** )。现在图片 **2017JanApr.jpg** 便可以成为一个索引,使得我可以不时地使用它来查看这个时期的所有图片。

|

||||

|

||||

### 注意内存消耗

|

||||

|

||||

你可能会好奇为什么我在上面的合成图中只特别指定了为期 4 个月(从一月到四月)的图片。因为 **montage** 将会消耗大量内存,所以你需要多加注意。我的相机产生的图片每张大约有 2.5MB,我发现我的系统可以很轻松地处理 60 张图片。但一旦图片增加到 80 张,如果此时还有另外的程序(例如 Firefox 、Thunderbird)在后台工作,那么我的电脑将会死机,这似乎和内存使用相关,**montage**可能会占用可用 RAM 的 80% 乃至更多(你可以在此期间运行 **top** 命令来查看内存占用)。假如我关掉其他的程序,我便可以在我的系统死机前处理 80 张图片。

|

||||

|

||||

下面的命令可以让你知晓在你运行 **montage** 命令前你需要处理图片张数:

|

||||

```

|

||||

ls 2017/0[1-4/*/*.JPG > filelist; wc -l filelist

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

**ls** 命令生成我们搜索的文件的列表,然后通过重定向将这个列表保存在任意以 filelist 为名称的文件中。接着带有 **-l** 选项的 **wc** 命令输出该列表文件共有多少行,换句话说,展示出需要处理的文件个数。下面是我运行命令后的输出:

|

||||

```

|

||||

163 filelist

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

啊呀!从一月到四月我居然有 163 张图片,使用这些图片来创建一张合成图一定会使得我的系统死机的。我需要将这个列表减少点,可能只处理到 3 月份或者更早的图片。但如果我在4月20号到30号期间拍摄了很多照片,我想这便是问题的所在。下面的命令便可以帮助指出这个问题:

|

||||

```

|

||||

ls 2017/0[1-3]/*/*.JPG > filelist; ls 2017/04/0[1-9]/*.JPG >> filelist; ls 2017/04/1[0-9]/*.JPG >> filelist; wc -l filelist

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

上面一行中共有 4 个命令,它们以分号分隔。第一个命令特别指定从一月到三月期间拍摄的照片;第二个命令使用 **>>** 将拍摄于 4 月 1 日至 9 日的照片追加到这个列表文件中;第三个命令将拍摄于 4 月 1 0 日到 19 日的照片追加到列表中。最终它的显示结果为:

|

||||

```

|

||||

81 filelist

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

我知道假如我关掉其他的程序,处理 81 张图片是可行的。

|

||||

|

||||

使用 **montage** 来处理它们是很简单的,因为我们只需要将上面所做的处理添加到 **montage** 命令的后面即可:

|

||||

```

|

||||

montage -label %d/%f -title 2017 -tile 5x -resize 10% -geometry +4+4 2017/0[1-3]/*/*.JPG 2017/04/0[1-9]/*.JPG 2017/04/1[0-9]/*.JPG 2017Jan01Apr19.jpg

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

从左到右,**montage** 命令后面最后的那个文件名将会作为输出,在它之前的都是输入。这个命令将花费大约 3 分钟来运行,并生成一张大小约为 2.5MB 的图片,但我的系统只是有一点反应迟钝而已。

|

||||

|

||||

### 展示合成图片

|

||||

|

||||

当你第一次使用 **display** 查看一张巨大的合成图片时,你将看到合成图的宽度很合适,但图片的高度被压缩了,以便和屏幕相适应。不要慌,只需要左击图片,然后选择 **View > Original Size** 便会显示整个图片。再次点击图片便可以使菜单栏隐藏。

|

||||

|

||||

我希望这篇文章可以在你使用新方法查看图片时帮助你。在我的下一篇文章中,我将讨论更加复杂的图片操作技巧。

|

||||

|

||||

### 作者简介

|

||||

Greg Pittman - Greg 肯塔基州路易斯维尔的一名退休的神经科医生,对计算机和程序设计有着长期的兴趣,最早可以追溯到 1960 年代的 Fortran IV 。当 Linux 和开源软件相继出现时,他开始学习更多的相关知识,并分享自己的心得。他是 Scribus 团队的成员。

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://opensource.com/article/17/9/imagemagick-viewing-images

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Greg Pittman][a]

|

||||

译者:[FSSlc](https://github.com/FSSlc)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:https://opensource.com/users/greg-p

|

||||

[1]:https://opensource.com/article/17/8/imagemagick

|

||||

[2]:/file/370946

|

||||

[3]:https://opensource.com/sites/default/files/u128651/edge3negate.jpg "Using the edge and negate options on an image."

|

||||

[4]:https://wiki.gnome.org/Apps/Shotwell

|

||||

[5]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exif

|

||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user