mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2024-12-26 21:30:55 +08:00

translated (#5726)

* 取消翻译,此篇其他平台已经有译文了 * translating by chenxinlong * deleted article removed by origin * translating * translating * keep translating * keep updating * keep updating * keep updating * keep updating * add content * finished translating * move to translated * mv to translated * remove the bullet symbol

This commit is contained in:

parent

5caa9f505d

commit

5c1d4d4d3a

@ -1,302 +0,0 @@

|

||||

Translating by chenxinlong

|

||||

An introduction to Linux's EXT4 filesystem

|

||||

============================================================

|

||||

|

||||

### Take a walk through EXT4's history, features, and optimal use, and learn how it differs from previous iterations of the EXT filesystem.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

>Image credits : [WIlliam][8][ Warby][9]. Modified by [Jason Baker][10]. Creative Commons [BY-SA 2.0][11].

|

||||

|

||||

In previous articles about Linux filesystems, I wrote [an introduction to Linux filesystems][12] and about some higher-level concepts such as [everything is a file][13]. I want to go into more detail about the specifics of the EXT filesystems, but first, let's answer the question, "What is a filesystem?" A filesystem is all of the following:

|

||||

|

||||

1. **Data storage: **The primary function of any filesystem is to be a structured place to store and retrieve data.

|

||||

|

||||

2. **Namespace: **A naming and organizational methodology that provides rules for naming and structuring data.

|

||||

|

||||

3. **Security model: **A scheme for defining access rights.

|

||||

|

||||

4. **API: **System function calls to manipulate filesystem objects like directories and files.

|

||||

|

||||

5. **Implementation: **The software to implement the above.

|

||||

|

||||

This article concentrates on the first item in the list and explores the metadata structures that provide the logical framework for data storage in an EXT filesystem.

|

||||

|

||||

### EXT filesystem history

|

||||

|

||||

Although written for Linux, the EXT filesystem has its roots in the Minix operating system and the Minix filesystem, which predate Linux by about five years, being first released in 1987\. Understanding the EXT4 filesystem is much easier if we look at the history and technical evolution of the EXT filesystem family from its Minix roots.

|

||||

|

||||

### Minix

|

||||

|

||||

When writing the original Linux kernel, Linus Torvalds needed a filesystem but didn't want to write one then. So he simply included the [Minix filesystem][14], which had been written by [Andrew S. Tanenbaum][15] and was a part of Tanenbaum's Minix operating system. [Minix][16] was a Unix-like operating system written for educational purposes. Its code was freely available and appropriately licensed to allow Torvalds to include it in his first version of Linux.

|

||||

|

||||

Minix has the following structures, most of which are located in the partition where the filesystem is generated:

|

||||

|

||||

* A [**boot sector**][6] in the first sector of the hard drive on which it is installed. The boot block includes a very small boot record and a partition table.

|

||||

|

||||

* The first block in each partition is a **superblock **that contains the metadata that defines the other filesystem structures and locates them on the physical disk assigned to the partition.

|

||||

|

||||

* An **inode bitmap block**, which determines which inodes are used and which are free.

|

||||

|

||||

* The **inodes**, which have their own space on the disk. Each inode contains information about one file, including the locations of the data blocks, i.e., zones belonging to the file.

|

||||

|

||||

* A **zone bitmap** to keep track of the used and free data zones.

|

||||

|

||||

* A **data zone**, in which the data is actually stored.

|

||||

|

||||

For both types of bitmaps, one bit represents one specific data zone or one specific inode. If the bit is zero, the zone or inode is free and available for use, but if the bit is one, the data zone or inode is in use.

|

||||

|

||||

What is an [inode][17]? Short for index-node, an inode is a 256-byte block on the disk and stores data about the file. This includes the file's size; the user IDs of the file's user and group owners; the file mode (i.e., the access permissions); and three timestamps specifying the time and date that: the file was last accessed, last modified, and the data in the inode was last modified.

|

||||

|

||||

The inode also contains data that points to the location of the file's data on the hard drive. In Minix and the EXT1-3 filesystems, this is a list of data zones or blocks. The Minix filesystem inodes supported nine data blocks, seven direct and two indirect. If you'd like to learn more, there is an excellent PDF with a detailed description of the [Minix filesystem structure][18] and a quick overview of the [inode pointer structure][19] on Wikipedia.

|

||||

|

||||

### EXT

|

||||

|

||||

The original [EXT filesystem][20] (Extended) was written by [Rémy Card][21] and released with Linux in 1992 to overcome some size limitations of the Minix filesystem. The primary structural changes were to the metadata of the filesystem, which was based on the Unix filesystem (UFS), which is also known as the Berkeley Fast File System (FFS). I found very little published information about the EXT filesystem that can be verified, apparently because it had significant problems and was quickly superseded by the EXT2 filesystem.

|

||||

|

||||

### EXT2

|

||||

|

||||

The [EXT2 filesystem][22] was quite successful. It was used in Linux distributions for many years, and it was the first filesystem I encountered when I started using Red Hat Linux 5.0 back in about 1997\. The EXT2 filesystem has essentially the same metadata structures as the EXT filesystem, however EXT2 is more forward-looking, in that a lot of disk space is left between the metadata structures for future use.

|

||||

|

||||

Like Minix, EXT2 has a [boot sector][23] in the first sector of the hard drive on which it is installed, which includes a very small boot record and a partition table. Then there is some reserved space after the boot sector, which spans the space between the boot record and the first partition on the hard drive that is usually on the next cylinder boundary. [GRUB2][24]—and possibly GRUB1—uses this space for part of its boot code.

|

||||

|

||||

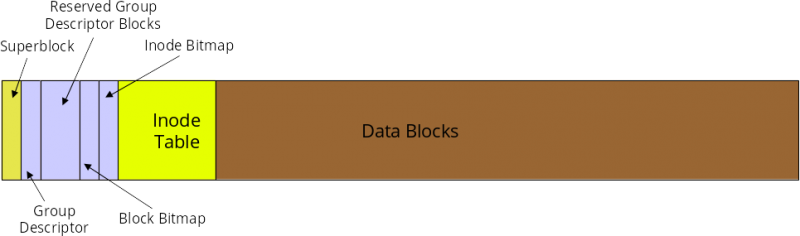

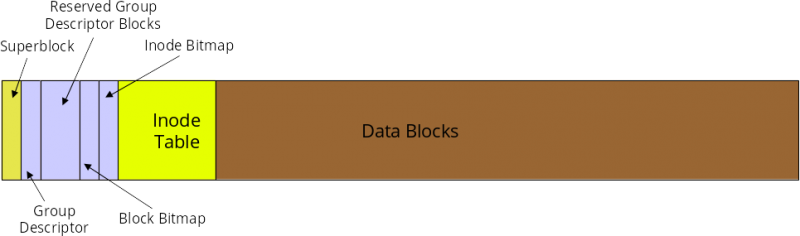

The space in each EXT2 partition is divided into cylinder groups that allow for more granular management of the data space. In my experience, the group size usually amounts to about 8MB. Figure 1, below, shows the basic structure of a cylinder group. The data allocation unit in a cylinder is the block, which is usually 4K in size.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Figure 1: The structure of a cylinder group in the EXT filesystems

|

||||

|

||||

The first block in the cylinder group is a superblock, which contains the metadata that defines the other filesystem structures and locates them on the physical disk. Some of the additional groups in the partition will have backup superblocks, but not all. A damaged superblock can be replaced by using a disk utility such as **dd** to copy the contents of a backup superblock to the primary superblock. It does not happen often, but once, many years ago, I had a damaged superblock, and I was able to restore its contents using one of the backup superblocks. Fortunately, I had been foresighted and used the **dumpe2fs** command to dump the descriptor information of the partitions on my system.

|

||||

|

||||

Following is the partial output from the **dumpe2fs** command. It shows the metadata contained in the superblock, as well as data about each of the first two cylinder groups in the filesystem.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

# dumpe2fs /dev/sda1

|

||||

Filesystem volume name: boot

|

||||

Last mounted on: /boot

|

||||

Filesystem UUID: 79fc5ed8-5bbc-4dfe-8359-b7b36be6eed3

|

||||

Filesystem magic number: 0xEF53

|

||||

Filesystem revision #: 1 (dynamic)

|

||||

Filesystem features: has_journal ext_attr resize_inode dir_index filetype needs_recovery extent 64bit flex_bg sparse_super large_file huge_file dir nlink extra_isize

|

||||

Filesystem flags: signed_directory_hash

|

||||

Default mount options: user_xattr acl

|

||||

Filesystem state: clean

|

||||

Errors behavior: Continue

|

||||

Filesystem OS type: Linux

|

||||

Inode count: 122160

|

||||

Block count: 488192

|

||||

Reserved block count: 24409

|

||||

Free blocks: 376512

|

||||

Free inodes: 121690

|

||||

First block: 0

|

||||

Block size: 4096

|

||||

Fragment size: 4096

|

||||

Group descriptor size: 64

|

||||

Reserved GDT blocks: 238

|

||||

Blocks per group: 32768

|

||||

Fragments per group: 32768

|

||||

Inodes per group: 8144

|

||||

Inode blocks per group: 509

|

||||

Flex block group size: 16

|

||||

Filesystem created: Tue Feb 7 09:33:34 2017

|

||||

Last mount time: Sat Apr 29 21:42:01 2017

|

||||

Last write time: Sat Apr 29 21:42:01 2017

|

||||

Mount count: 25

|

||||

Maximum mount count: -1

|

||||

Last checked: Tue Feb 7 09:33:34 2017

|

||||

Check interval: 0 (<none>)

|

||||

Lifetime writes: 594 MB

|

||||

Reserved blocks uid: 0 (user root)

|

||||

Reserved blocks gid: 0 (group root)

|

||||

First inode: 11

|

||||

Inode size: 256

|

||||

Required extra isize: 32

|

||||

Desired extra isize: 32

|

||||

Journal inode: 8

|

||||

Default directory hash: half_md4

|

||||

Directory Hash Seed: c780bac9-d4bf-4f35-b695-0fe35e8d2d60

|

||||

Journal backup: inode blocks

|

||||

Journal features: journal_64bit

|

||||

Journal size: 32M

|

||||

Journal length: 8192

|

||||

Journal sequence: 0x00000213

|

||||

Journal start: 0

|

||||

|

||||

Group 0: (Blocks 0-32767)

|

||||

Primary superblock at 0, Group descriptors at 1-1

|

||||

Reserved GDT blocks at 2-239

|

||||

Block bitmap at 240 (+240)

|

||||

Inode bitmap at 255 (+255)

|

||||

Inode table at 270-778 (+270)

|

||||

24839 free blocks, 7676 free inodes, 16 directories

|

||||

Free blocks: 7929-32767

|

||||

Free inodes: 440, 470-8144

|

||||

Group 1: (Blocks 32768-65535)

|

||||

Backup superblock at 32768, Group descriptors at 32769-32769

|

||||

Reserved GDT blocks at 32770-33007

|

||||

Block bitmap at 241 (bg #0 + 241)

|

||||

Inode bitmap at 256 (bg #0 + 256)

|

||||

Inode table at 779-1287 (bg #0 + 779)

|

||||

8668 free blocks, 8142 free inodes, 2 directories

|

||||

Free blocks: 33008-33283, 33332-33791, 33974-33975, 34023-34092, 34094-34104, 34526-34687, 34706-34723, 34817-35374, 35421-35844, 35935-36355, 36357-36863, 38912-39935, 39940-40570, 42620-42623, 42655, 42674-42687, 42721-42751, 42798-42815, 42847, 42875-42879, 42918-42943, 42975, 43000-43007, 43519, 43559-44031, 44042-44543, 44545-45055, 45116-45567, 45601-45631, 45658-45663, 45689-45695, 45736-45759, 45802-45823, 45857-45887, 45919, 45950-45951, 45972-45983, 46014-46015, 46057-46079, 46112-46591, 46921-47103, 49152-49395, 50027-50355, 52237-52255, 52285-52287, 52323-52351, 52383, 52450-52479, 52518-52543, 52584-52607, 52652-52671, 52734-52735, 52743-53247

|

||||

Free inodes: 8147-16288

|

||||

Group 2: (Blocks 65536-98303)

|

||||

Block bitmap at 242 (bg #0 + 242)

|

||||

Inode bitmap at 257 (bg #0 + 257)

|

||||

Inode table at 1288-1796 (bg #0 + 1288)

|

||||

6326 free blocks, 8144 free inodes, 0 directories

|

||||

Free blocks: 67042-67583, 72201-72994, 80185-80349, 81191-81919, 90112-94207

|

||||

Free inodes: 16289-24432

|

||||

Group 3: (Blocks 98304-131071)

|

||||

|

||||

<snip>

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Each cylinder group has its own inode bitmap that is used to determine which inodes are used and which are free within that group. The inodes have their own space in each group. Each inode contains information about one file, including the locations of the data blocks belonging to the file. The block bitmap keeps track of the used and free data blocks within the filesystem. Notice that there is a great deal of data about the filesystem in the output shown above. On very large filesystems the group data can run to hundreds of pages in length. The group metadata includes a listing of all of the free data blocks in the group.

|

||||

|

||||

The EXT filesystem implemented data-allocation strategies that ensured minimal file fragmentation. Reducing fragmentation improved filesystem performance. Those strategies are described below, in the section on EXT4.

|

||||

|

||||

The biggest problem with the EXT2 filesystem, which I encountered on some occasions, was that it could take many hours to recover after a crash because the **fsck** (file system check) program took a very long time to locate and correct any inconsistencies in the filesystem. It once took over 28 hours on one of my computers to fully recover a disk upon reboot after a crash—and that was when disks were measured in the low hundreds of megabytes in size.

|

||||

|

||||

### EXT3

|

||||

|

||||

The [EXT3 filesystem][25] had the singular objective of overcoming the massive amounts of time that the **fsck** program required to fully recover a disk structure damaged by an improper shutdown that occurred during a file-update operation. The only addition to the EXT filesystem was the [journal][26], which records in advance the changes that will be performed to the filesystem. The rest of the disk structure is the same as it was in EXT2.

|

||||

|

||||

Instead of writing data to the disk's data areas directly, as in previous versions, the journal in EXT3 writes file data, along with its metadata, to a specified area on the disk. Once the data is safely on the hard drive, it can be merged in or appended to the target file with almost zero chance of losing data. As this data is committed to the data area of the disk, the journal is updated so that the filesystem will remain in a consistent state in the event of a system failure before all the data in the journal is committed. On the next boot, the filesystem will be checked for inconsistencies, and data remaining in the journal will then be committed to the data areas of the disk to complete the updates to the target file.

|

||||

|

||||

Journaling does reduce data-write performance, however there are three options available for the journal that allow the user to choose between performance and data integrity and safety. My personal preference is on the side of safety because my environments do not require heavy disk-write activity.

|

||||

|

||||

The journaling function reduces the time required to check the hard drive for inconsistencies after a failure from hours (or even days) to mere minutes, at the most. I have had many issues over the years that have crashed my systems. The details could fill another article, but suffice it to say that most were self-inflicted, like kicking out a power plug. Fortunately, the EXT journaling filesystems have reduced that bootup recovery time to two or three minutes. In addition, I have never had a problem with lost data since I started using EXT3 with journaling.

|

||||

|

||||

The journaling feature of EXT3 can be turned off and it then functions as an EXT2 filesystem. The journal itself still exists, empty and unused. Simply remount the partition with the mount command using the type parameter to specify EXT2\. You may be able to do this from the command line, depending upon which filesystem you are working with, but you can change the type specifier in the **/etc/fstab** file and then reboot. I strongly recommend against mounting an EXT3 filesystem as EXT2 because of the additional potential for lost data and extended recovery times.

|

||||

|

||||

An existing EXT2 filesystem can be upgraded to EXT3 with the addition of a journal using the following command.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

tune2fs -j /dev/sda1

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Where **/dev/sda1** is the drive and partition identifier. Be sure to change the file type specifier in **/etc/fstab** and remount the partition or reboot the system to have the change take effect.

|

||||

|

||||

### EXT4

|

||||

|

||||

The [EXT4 filesystem][27] primarily improves performance, reliability, and capacity. To improve reliability, metadata and journal checksums were added. To meet various mission-critical requirements, the filesystem timestamps were improved with the addition of intervals down to nanoseconds. The addition of two high-order bits in the timestamp field defers the [Year 2038 problem][28] until 2446—for EXT4 filesystems, at least.

|

||||

|

||||

In EXT4, data allocation was changed from fixed blocks to extents. An extent is described by its starting and ending place on the hard drive. This makes it possible to describe very long, physically contiguous files in a single inode pointer entry, which can significantly reduce the number of pointers required to describe the location of all the data in larger files. Other allocation strategies have been implemented in EXT4 to further reduce fragmentation.

|

||||

|

||||

EXT4 reduces fragmentation by scattering newly created files across the disk so that they are not bunched up in one location at the beginning of the disk, as many early PC filesystems did. The file-allocation algorithms attempt to spread the files as evenly as possible among the cylinder groups and, when fragmentation is necessary, to keep the discontinuous file extents as close as possible to others in the same file to minimize head seek and rotational latency as much as possible. Additional strategies are used to pre-allocate extra disk space when a new file is created or when an existing file is extended. This helps to ensure that extending the file will not automatically result in its becoming fragmented. New files are never allocated immediately after existing files, which also prevents fragmentation of the existing files.

|

||||

|

||||

Aside from the actual location of the data on the disk, EXT4 uses functional strategies, such as delayed allocation, to allow the filesystem to collect all the data being written to the disk before allocating space to it. This can improve the likelihood that the data space will be contiguous.

|

||||

|

||||

Older EXT filesystems, such as EXT2 and EXT3, can be mounted as EXT4 to make some minor performance gains. Unfortunately, this requires turning off some of the important new features of EXT4, so I recommend against this.

|

||||

|

||||

EXT4 has been the default filesystem for Fedora since Fedora 14\. An EXT3 filesystem can be upgraded to EXT4 using the [procedure ][29]described in the Fedora documentation, however its performance will still suffer due to residual EXT3 metadata structures. The best method for upgrading to EXT4 from EXT3 is to back up all the data on the target filesystem partition, use the **mkfs** command to write an empty EXT4 filesystem to the partition, and then restore all the data from the backup.

|

||||

|

||||

### Inode

|

||||

|

||||

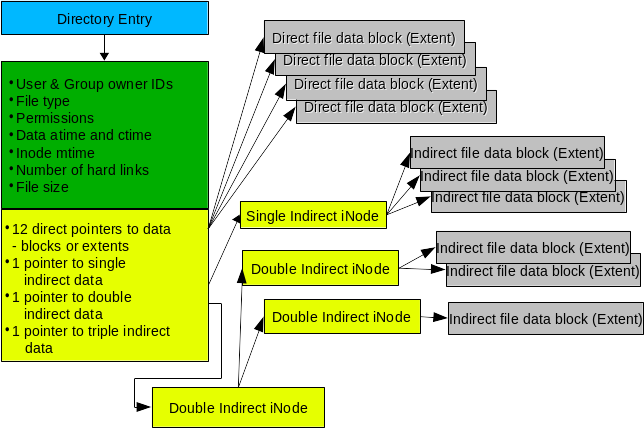

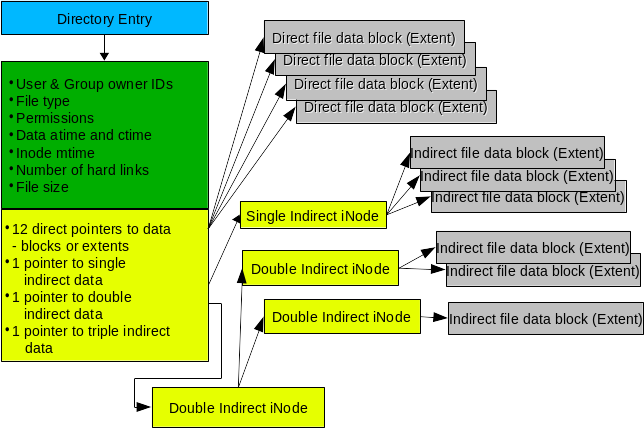

The inode, described previously, is a key component of the metadata in EXT filesystems. Figure 2 shows the relationship between the inode and the data stored on the hard drive. This diagram is the directory and inode for a single file which, in this case, may be highly fragmented. The EXT filesystems work actively to reduce fragmentation, so it is very unlikely you will ever see a file with this many indirect data blocks or extents. In fact, as you will see below, fragmentation is extremely low in EXT filesystems, so most inodes will use only one or two direct data pointers and none of the indirect pointers.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Figure 2: The inode stores information about each file and enables the EXT filesystem to locate all data belonging to it.

|

||||

|

||||

The inode does not contain the name of the file. Access to a file is via the directory entry, which itself is the name of the file and contains a pointer to the inode. The value of that pointer is the inode number. Each inode in a filesystem has a unique ID number, but inodes in other filesystems on the same computer (and even the same hard drive) can have the same inode number. This has implications for [links][30], and this discussion is beyond the scope of this article.

|

||||

|

||||

The inode contains the metadata about the file, including its type and permissions as well as its size. The inode also contains space for 15 pointers that describe the location and length of data blocks or extents in the data portion of the cylinder group. Twelve of the pointers provide direct access to the data extents and should be sufficient to handle most files. However, for files that have significant fragmentation, it becomes necessary to have some additional capabilities in the form of indirect nodes. Technically these are not really inodes, so I use the term "node" here for convenience.

|

||||

|

||||

An indirect node is a normal data block in the filesystem that is used only for describing data and not for storage of metadata, thus more than 15 entries can be supported. For example, a block size of 4K can support 512 4-byte indirect nodes, allowing **12 (direct) + 512 (indirect) = 524** extents for a single file. Double and triple indirect node support is also supported, but most of us are unlikely to encounter files requiring that many extents.

|

||||

|

||||

### Data fragmentation

|

||||

|

||||

For many older PC filesystems, such as FAT (and all its variants) and NTFS, fragmentation has been a significant problem resulting in degraded disk performance. Defragmentation became an industry in itself with different brands of defragmentation software that ranged from very effective to only marginally so.

|

||||

|

||||

Linux's extended filesystems use data-allocation strategies that help to minimize fragmentation of files on the hard drive and reduce the effects of fragmentation when it does occur. You can use the **fsck** command on EXT filesystems to check the total filesystem fragmentation. The following example checks the home directory of my main workstation, which was only 1.5% fragmented. Be sure to use the **-n** parameter, because it prevents **fsck** from taking any action on the scanned filesystem.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

fsck -fn /dev/mapper/vg_01-home

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

I once performed some theoretical calculations to determine whether disk defragmentation might result in any noticeable performance improvement. While I did make some assumptions, the disk performance data I used were from a new 300GB, Western Digital hard drive with a 2.0ms track-to-track seek time. The number of files in this example was the actual number that existed in the filesystem on the day I did the calculation. I did assume that a fairly large amount of the fragmented files (20%) would be touched each day.

|

||||

|

||||

| **Total files** | **271,794** |

|

||||

| % fragmentation | 5.00% |

|

||||

| Discontinuities | 13,590 |

|

||||

| | |

|

||||

| % fragmented files touched per day | 20% (assume) |

|

||||

| Number of additional seeks | 2,718 |

|

||||

| Average seek time | 10.90 ms |

|

||||

| Total additional seek time per day | 29.63 sec |

|

||||

| | 0.49 min |

|

||||

| | |

|

||||

| Track-to-track seek time | 2.00 ms |

|

||||

| Total additional seek time per day | 5.44 sec |

|

||||

| | 0.091 min |

|

||||

|

||||

Table 1: The theoretical effects of fragmentation on disk performance

|

||||

|

||||

I have done two calculations for the total additional seek time per day, one based on the track-to-track seek time, which is the more likely scenario for most files due to the EXT file allocation strategies, and one for the average seek time, which I assumed would make a fair worst-case scenario.

|

||||

|

||||

As you can see from Table 1, the impact of fragmentation on a modern EXT filesystem with a hard drive of even modest performance would be minimal and negligible for the vast majority of applications. You can plug the numbers from your environment into your own similar spreadsheet to see what you might expect in the way of performance impact. This type of calculation most likely will not represent actual performance, but it can provide a bit of insight into fragmentation and its theoretical impact on a system.

|

||||

|

||||

Most of my partitions are around 1.5% or 1.6% fragmented; I do have one that is 3.3% fragmented but that is a large, 128GB filesystem with fewer than 100 very large ISO image files; I've had to expand the partition several times over the years as it got too full.

|

||||

|

||||

That is not to say that some application environments don't require greater assurance of even less fragmentation. The EXT filesystem can be tuned with care by a knowledgeable admin who can adjust the parameters to compensate for specific workload types. This can be done when the filesystem is created or later using the **tune2fs** command. The results of each tuning change should be tested, meticulously recorded, and analyzed to ensure optimum performance for the target environment. In the worst case, where performance cannot be improved to desired levels, other filesystem types are available that may be more suitable for a particular workload. And remember that it is common to mix filesystem types on a single host system to match the load placed on each filesystem.

|

||||

|

||||

Due to the low amount of fragmentation on most EXT filesystems, it is not necessary to defragment. In any event, there is no safe defragmentation tool for EXT filesystems. There are a few tools that allow you to check the fragmentation of an individual file or the fragmentation of the remaining free space in a filesystem. There is one tool, **e4defrag**, which will defragment a file, directory, or filesystem as much as the remaining free space will allow. As its name implies, it only works on files in an EXT4 filesystem, and it does have some limitations.

|

||||

|

||||

If it becomes necessary to perform a complete defragmentation on an EXT filesystem, there is only one method that will work reliably. You must move all the files from the filesystem to be defragmented, ensuring that they are deleted after being safely copied to another location. If possible, you could then increase the size of the filesystem to help reduce future fragmentation. Then copy the files back onto the target filesystem. Even this does not guarantee that all the files will be completely defragmented.

|

||||

|

||||

### Conclusions

|

||||

|

||||

The EXT filesystems have been the default for many Linux distributions for more than 20 years. They offer stability, high capacity, reliability, and performance while requiring minimal maintenance. I have tried other filesystems but always return to EXT. Every place I have worked with Linux has used the EXT filesystems and found them suitable for all the mainstream loads used on them. Without a doubt, the EXT4 filesystem should be used for most Linux systems unless there is a compelling reason to use another filesystem.

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

作者简介:

|

||||

|

||||

David Both - David Both is a Linux and Open Source advocate who resides in Raleigh, North Carolina. He has been in the IT industry for over forty years and taught OS/2 for IBM where he worked for over 20 years. While at IBM, he wrote the first training course for the original IBM PC in 1981. He has taught RHCE classes for Red Hat and has worked at MCI Worldcom, Cisco, and the State of North Carolina. He has been working with Linux and Open Source Software for almost 20 years.

|

||||

|

||||

-------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://opensource.com/article/17/5/introduction-ext4-filesystem

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[David Both ][a]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/chenxinlong)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:https://opensource.com/users/dboth

|

||||

[1]:https://opensource.com/resources/what-is-linux?src=linux_resource_menu

|

||||

[2]:https://opensource.com/resources/what-are-linux-containers?src=linux_resource_menu

|

||||

[3]:https://developers.redhat.com/promotions/linux-cheatsheet/?intcmp=7016000000127cYAAQ

|

||||

[4]:https://developers.redhat.com/cheat-sheet/advanced-linux-commands-cheatsheet?src=linux_resource_menu&intcmp=7016000000127cYAAQ

|

||||

[5]:https://opensource.com/tags/linux?src=linux_resource_menu

|

||||

[6]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boot_sector

|

||||

[7]:https://opensource.com/article/17/5/introduction-ext4-filesystem?rate=B4QU3W_JYmEKsIKZf5yqMpztt7CRF6uzC0wfNBidEbs

|

||||

[8]:https://www.flickr.com/photos/wwarby/11644168395

|

||||

[9]:https://www.flickr.com/photos/wwarby/11644168395

|

||||

[10]:https://opensource.com/users/jason-baker

|

||||

[11]:https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

|

||||

[12]:https://opensource.com/life/16/10/introduction-linux-filesystems

|

||||

[13]:https://opensource.com/life/15/9/everything-is-a-file

|

||||

[14]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MINIX_file_system

|

||||

[15]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_S._Tanenbaum

|

||||

[16]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MINIX

|

||||

[17]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inode

|

||||

[18]:http://ohm.hgesser.de/sp-ss2012/Intro-MinixFS.pdf

|

||||

[19]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inode_pointer_structure

|

||||

[20]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extended_file_system

|

||||

[21]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R%C3%A9my_Card

|

||||

[22]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ext2

|

||||

[23]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boot_sector

|

||||

[24]:https://opensource.com/article/17/2/linux-boot-and-startup

|

||||

[25]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ext3

|

||||

[26]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Journaling_file_system

|

||||

[27]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ext4

|

||||

[28]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Year_2038_problem

|

||||

[29]:https://docs.fedoraproject.org/en-US/Fedora/14/html/Storage_Administration_Guide/ext4converting.html

|

||||

[30]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hard_link

|

||||

[31]:https://opensource.com/user/14106/feed

|

||||

[32]:https://opensource.com/article/17/5/introduction-ext4-filesystem#comments

|

||||

[33]:https://opensource.com/users/dboth

|

||||

@ -0,0 +1,301 @@

|

||||

Linux 的 EXT4 文件系统简介

|

||||

============================================================

|

||||

|

||||

### 让我们大概地从 EXT4 的历史、特性以及最佳实践这几个方面来学习它和之前的所有的 EXT 文件系统有何不同。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

>图片来自 : [WIlliam][8][ Warby][9]. 由 [Jason Baker][10] 编辑. Creative Commons [BY-SA 2.0][11].

|

||||

|

||||

在之前关于 Linux 文件系统的文章里,我写过一篇 [an introduction to Linux filesystems][12] 和一些更高级的概念例如 [everything is a file][13]. 我想要更深入地了解 EXT 文件系统的特性的详细内容,但是首先让我们来回答一个问题,“什么样才算是一个文件系统 ?” 一个文件系统应该涵盖以下所有点:

|

||||

|

||||

1. **数据存储:** 对于任何一个文件系统来说,一个最主要的功能就是能够被当作一个容器结构来存储和恢复数据。

|

||||

|

||||

2. **命名空间:** 命名空间是一个提供了命名规则和数据结构的用于命名与组织的方法学。

|

||||

|

||||

3. **安全模型:** 一个用于定义访问权限的策略。

|

||||

|

||||

4. **API:** 指的是调用了操作这个系统的对象的系统方法,这些对象诸如目录和文件。

|

||||

|

||||

5. **实现:** 能够实现以上几点的软件。

|

||||

|

||||

本文内容的讨论主要集中于上述几点中的第一项并探索为一个 EXT 文件系统的数据存储提供逻辑框架的元数据结构。

|

||||

|

||||

### EXT 文件系统历史

|

||||

|

||||

虽然 EXT 文件系统是为 Linux 编写的,但其真正起源于 Minix 操作系统和 Minix 文件系统,而 Minix 最早发布于 1987,早于 Linux 5 年。如果我们从 EXT 文件系统大家族的 Minix 起源来观察其历史与技术发展那么理解 EXT4 文件系统就会简单得多。

|

||||

|

||||

### Minix

|

||||

|

||||

当 Linux Torvalds 在写最初的 Linux 内核的时候,他需要一个文件系统但是他又不想自己写一个。于是他简单地把 [Minix 文件系统][14] 加了进去,这个 Minix 文件系统是由 [Andrew S. Tanenbaum][15] 写的同时也是 Tanenbaum 的 Minix 操作系统的一部分。[Minix][16] 是一个类 Unix 风格的操作系统,最初编写它的原因是用于教育。Minx 的代码是自由可用的且经过适当的许可的,所以 Torvalds 可以把它用 Linux 的最初版本里。

|

||||

|

||||

Minix 有以下这些结构,其中的大部分位于生成文件系统的分区中:

|

||||

|

||||

* [**boot 扇区**][6] 是硬盘驱动安装后的第一个扇区。这个 boot 块包含了一个非常小的 boot 记录和一个分区表。

|

||||

|

||||

* 每一个分区的第一个块都是一个包含了元数据的 **superblock** ,这些元数据定义了其他文件系统的结构并将其定位于物理硬盘的具体分区上。

|

||||

|

||||

* 一个 **inode 位图块** 决定了哪些 inode 是在使用中的,哪一些是未使用的。

|

||||

|

||||

* **inode** 在硬盘上有它们自己的空间。每一个 inode 都包含了一个文件的信息包括其所处的数据块的位置,也就是该文件所处的区域。

|

||||

|

||||

* 一个 **区位图** 用于保持追踪数据区域的使用和未使用情况。

|

||||

|

||||

* 一个 **数据区**, 这里是数据存储的地方。

|

||||

|

||||

对上述了两种位图类型来说,一个 bit 表示一个制定的数据区或者一个指定的 inode. 如果这个 bit 是 0 则表示这个数据区或者这个 inode 是可以使用的,如果是 1 则表示正在使用中。

|

||||

|

||||

那么,[inode][17] 又是什么呢 ? 就是 index-node (索引节点)的简写。 inode 是位于磁盘上的一个 256 字节的块,用于存储和该 inode 对应的文件的相关数据。这些数据包含了文件的大小、文件的所有者和所属组的用户的 ID、文件模式(即访问权限)以及三个时间戳用于指定:该文件最后的访问时间、该文件的最后修改时间和该 inode 中的数据的最后修改时间。

|

||||

|

||||

同时,这个 inode 还包含了指向了其所对应的文件的数据在硬盘中的位置。在 Minix 和 EXT1-3 文件系统中,inode 表示的是一系列的的数据区和块。Minix 文件系统的 inode 支持 9 个数据块包括 7 个直接数据块和 2 个间接数据块。如果你想要更深入的了解,这里有一个优秀的 PDF 详细地描述了 [Minix 文件系统街头][18] 。同时你也可以在维基百科上对 [inode 指针结构][19] 做一个快速的浏览。

|

||||

|

||||

### EXT

|

||||

|

||||

原生的 [EXT 文件系统][20] (指经过扩展的) 是由 [Rémy Card][21] 编写并于 1992 年与 Linux 一同发行。主要是为了克服 Minix 文件系统中的一些文件大小限制的问题。其中,最主要的结构变化就是文件系统中的元数据。它基于 Unix 文件系统 (UFS),也被称为伯克利快速文件系统(FFS)。我发现只有很少一部分关于 EXT 文件系统的发行信息是可以被验证的,显然这是因为其存在着严重的问题并且它很快地被 EXT2 文件系统取代了。

|

||||

|

||||

### EXT2

|

||||

|

||||

[EXT2 文件系统][22] 就相当地成功,它在 Linux 发行版中存活了多年。它是我在 1997 年开始使用 Red Hat Linux 时认识的第一个文件系统。实际上,EXT2 文件系统有着和 EXT 文件系统基本相同的元数据结构。然而 EXT2 更高瞻远瞩,因为其元数据结构之间留有很多磁盘空间供将来使用。

|

||||

|

||||

和 Minix 类似,EXT2 也有一个[boot 扇区][23] ,它是硬盘驱动安装后的第一个扇区。它包含了少量的 boot 记录和一个分区表。接着 boot 扇区之后是一些保留的空间,它跨越引导记录和通常位于下一个柱面的硬盘驱动器上的第一个分区之间的空间。 [GRUB2] [24] - 也可能是GRUB1 - 将此空间用于其部分启动代码。

|

||||

|

||||

每个 EXT2 分区中的空间分为各柱面组,它允许更精细地管理数据空间。 根据我的经验,每一组大小通常约为8MB。 下面的图1显示了一个柱面组的基本结构。 柱面中的数据分配单元是块,通常大小为4K。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Figure 1: EXT 文件系统中的柱面组的结构

|

||||

|

||||

柱面组中的第一个块是一个超级块,它包含了一个定义了其他文件系统的结构并将其定位于物理硬盘的具体分区上的元数据。分区中有一些柱面组还会有备用超级块,但并不是所有的柱面组都有。我们还可以使用例如 **dd** 等磁盘工具来拷贝备用超级块的内容到主超级块上以达到更换损坏超级块的目的。虽然这种情况不会经常发生,但是在几年前我的一个超级块损坏了,我就是用这种方法来修复的。幸好,我很有先见之明地使用了 **dumpe2fs** 命令来备份了我的分区描述符信息到我的系统上。

|

||||

|

||||

以下是 **dumpe2fs** 命令的一部分输出。这部分输出主要是超级块上包含的一些元数据,同时也是文件系统上的前两个柱面组的数据。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

# dumpe2fs /dev/sda1

|

||||

Filesystem volume name: boot

|

||||

Last mounted on: /boot

|

||||

Filesystem UUID: 79fc5ed8-5bbc-4dfe-8359-b7b36be6eed3

|

||||

Filesystem magic number: 0xEF53

|

||||

Filesystem revision #: 1 (dynamic)

|

||||

Filesystem features: has_journal ext_attr resize_inode dir_index filetype needs_recovery extent 64bit flex_bg sparse_super large_file huge_file dir nlink extra_isize

|

||||

Filesystem flags: signed_directory_hash

|

||||

Default mount options: user_xattr acl

|

||||

Filesystem state: clean

|

||||

Errors behavior: Continue

|

||||

Filesystem OS type: Linux

|

||||

Inode count: 122160

|

||||

Block count: 488192

|

||||

Reserved block count: 24409

|

||||

Free blocks: 376512

|

||||

Free inodes: 121690

|

||||

First block: 0

|

||||

Block size: 4096

|

||||

Fragment size: 4096

|

||||

Group descriptor size: 64

|

||||

Reserved GDT blocks: 238

|

||||

Blocks per group: 32768

|

||||

Fragments per group: 32768

|

||||

Inodes per group: 8144

|

||||

Inode blocks per group: 509

|

||||

Flex block group size: 16

|

||||

Filesystem created: Tue Feb 7 09:33:34 2017

|

||||

Last mount time: Sat Apr 29 21:42:01 2017

|

||||

Last write time: Sat Apr 29 21:42:01 2017

|

||||

Mount count: 25

|

||||

Maximum mount count: -1

|

||||

Last checked: Tue Feb 7 09:33:34 2017

|

||||

Check interval: 0 (<none>)

|

||||

Lifetime writes: 594 MB

|

||||

Reserved blocks uid: 0 (user root)

|

||||

Reserved blocks gid: 0 (group root)

|

||||

First inode: 11

|

||||

Inode size: 256

|

||||

Required extra isize: 32

|

||||

Desired extra isize: 32

|

||||

Journal inode: 8

|

||||

Default directory hash: half_md4

|

||||

Directory Hash Seed: c780bac9-d4bf-4f35-b695-0fe35e8d2d60

|

||||

Journal backup: inode blocks

|

||||

Journal features: journal_64bit

|

||||

Journal size: 32M

|

||||

Journal length: 8192

|

||||

Journal sequence: 0x00000213

|

||||

Journal start: 0

|

||||

|

||||

Group 0: (Blocks 0-32767)

|

||||

Primary superblock at 0, Group descriptors at 1-1

|

||||

Reserved GDT blocks at 2-239

|

||||

Block bitmap at 240 (+240)

|

||||

Inode bitmap at 255 (+255)

|

||||

Inode table at 270-778 (+270)

|

||||

24839 free blocks, 7676 free inodes, 16 directories

|

||||

Free blocks: 7929-32767

|

||||

Free inodes: 440, 470-8144

|

||||

Group 1: (Blocks 32768-65535)

|

||||

Backup superblock at 32768, Group descriptors at 32769-32769

|

||||

Reserved GDT blocks at 32770-33007

|

||||

Block bitmap at 241 (bg #0 + 241)

|

||||

Inode bitmap at 256 (bg #0 + 256)

|

||||

Inode table at 779-1287 (bg #0 + 779)

|

||||

8668 free blocks, 8142 free inodes, 2 directories

|

||||

Free blocks: 33008-33283, 33332-33791, 33974-33975, 34023-34092, 34094-34104, 34526-34687, 34706-34723, 34817-35374, 35421-35844, 35935-36355, 36357-36863, 38912-39935, 39940-40570, 42620-42623, 42655, 42674-42687, 42721-42751, 42798-42815, 42847, 42875-42879, 42918-42943, 42975, 43000-43007, 43519, 43559-44031, 44042-44543, 44545-45055, 45116-45567, 45601-45631, 45658-45663, 45689-45695, 45736-45759, 45802-45823, 45857-45887, 45919, 45950-45951, 45972-45983, 46014-46015, 46057-46079, 46112-46591, 46921-47103, 49152-49395, 50027-50355, 52237-52255, 52285-52287, 52323-52351, 52383, 52450-52479, 52518-52543, 52584-52607, 52652-52671, 52734-52735, 52743-53247

|

||||

Free inodes: 8147-16288

|

||||

Group 2: (Blocks 65536-98303)

|

||||

Block bitmap at 242 (bg #0 + 242)

|

||||

Inode bitmap at 257 (bg #0 + 257)

|

||||

Inode table at 1288-1796 (bg #0 + 1288)

|

||||

6326 free blocks, 8144 free inodes, 0 directories

|

||||

Free blocks: 67042-67583, 72201-72994, 80185-80349, 81191-81919, 90112-94207

|

||||

Free inodes: 16289-24432

|

||||

Group 3: (Blocks 98304-131071)

|

||||

|

||||

<snip>

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

每一个柱面组都有自己的 inode 位图用于判定该柱面组中的哪些 inode 是使用中的而哪些又是未被使用的。每一个柱面组的 inode 都有它们自己的空间。每一个 inode 都包含了对应的文件的相关信息,包括其位于该文件的数据块中的位置。这个块位图纪录了文件系统中的使用中和非使用中的数据块。请注意,在上面的输出中有大量关于文件系统的数据。在非常大的文件系统上,组数据可以运行到数百页的长度。 组元数据包括组中所有空闲数据块的列表。

|

||||

|

||||

EXT 文件系统实现了数据分配策略以确保产生最少的文件碎片。减少文件碎片可以提高文件系统的性能。这些策略会在下面的 EXT4 中描述到。

|

||||

|

||||

我所遇见的关于 EXT2 文件系统最大的问题是 **fsck** (文件系统检查) 程序这一环节占用了很长一段时间来定位和校准文件系统中的所有不一致性导致其共花费了数个小时来修复一个崩溃。有一次我的其中一台电脑共花费了 28 个小时在一次崩溃后重新启动时恢复磁盘上,并且是在磁盘被检测量在几百兆字节大小的情况下。

|

||||

|

||||

### EXT3

|

||||

|

||||

[EXT3 文件系统][25] 具有克服 **fsck** 程序需要完全恢复在文件更新操作期间发生的不正确关机损坏的磁盘结构所需的大量时间的单一目标。EXT 文件系统的唯一新增是 [日志][26],它将提前记录将对文件系统执行的更改。 磁盘结构的其余部分与 EXT2 中的相同。

|

||||

|

||||

作为一个先前的版本,除了直接写入数据到磁盘的数据区域外,EXT3 的日志在写入元数据时同时会也写入文件数据到磁盘上的一个指定数据区域。一旦这些数据安全地到达硬盘,它就可以几乎零丢失率地被合并或者被追加到目标文件。当这些数据被提交到磁盘上的数据区域上,这些日志就会随即更新,这样在系统发生故障之前,文件系统将保持一致状态,才能提交日志中的所有数据。在下次启动时,将检查文件系统的不一致性,然后将日志中保留的数据提交到磁盘的数据区,以完成对目标文件的更新。

|

||||

|

||||

日记功能确实降低了数据写入性能,但是有三个可用于日志的选项,允许用户在性能和数据完整性和安全性之间进行选择。 我的个人更偏向于选择安全性,因为我的环境不需要大量的磁盘写入活动。

|

||||

|

||||

日志功能减少了在从几小时(甚至几天)到几分钟之间的失败后检查硬盘驱动器所需的时间。 多年来,我遇到了很多问题导致了我的系统崩溃。要详细说的话恐怕还得再写一篇文章,但这足以说明大多数是我自己造成的,就比如不小心踢掉一个电源插头。 幸运的是,EXT日志文件系统将启动恢复时间缩短到两三分钟。 此外,自从我开始使用带日志记录的EXT3,我从来没有遇到丢失数据的问题。

|

||||

|

||||

EXT3 的日志功能可以关闭,然后作为 EXT2 文件系统。 该日志本身仍然是存在的,只是状态为空且未使用。 只需使用类型参数使用 mount 命令来 remount 到分区即可指定EXT2 \。 你可以从命令行执行此操作,但是具体还是取决于你正在使用的文件系统,但你可以更改 **/ etc / fstab** 文件中的类型说明符,然后重新启动。 我强烈建议不要将 EXT3文件系统安装为 EXT2 ,因为这会具有丢失数据和增加恢复时间的潜在可能性。

|

||||

|

||||

EXT2 文件系统可以使用如下命令来通过日志升级到 EXT3 。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

tune2fs -j /dev/sda1

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

**/dev/sda1** 表示驱动和分区的标识符。同时要注意修改 **/etc/fstab** 中的文件类型标识符并 remount 分区或者重启系统以确保修改生效。

|

||||

|

||||

### EXT4

|

||||

|

||||

[EXT4 filesystem][27]主要提高了性能、可靠性和容量。位了提高可靠性,它新增了元数据和日志校验和。同时位了满足各种关键任务要求,文件系统新增了纳秒级别的时间戳。在时间戳字段中添加两个高位来延迟时间戳的 [2038 年的问题][28] ,在 EXT4 文件系统至少可达到 2446 年。

|

||||

|

||||

在 EXT4 中,数据分配从固定块更改为盘区,盘区由硬盘驱动器上的开始和结束位置来描述。这使得可以在单个 inode 指针条目中描述非常长的物理连续的文件,这可以显着减少描述大文件中所有数据的位置所需的指针数。 EXT4 中已经实施了其他分配策略,以进一步减少碎片化。

|

||||

|

||||

EXT4 通过将新创建的文件分散在磁盘上,从而使其不会全部聚集在磁盘起始位置,就像早期的PC文件系统一样,减少了碎片。文件分配算法尝试在柱面组中尽可能均匀地扩展文件,并且当需要分段时,要使不连续文件扩展区尽可能靠近同一文件中的其他文件,以尽可能减少头部搜索和旋转等待时间尽可能的当创建新文件或扩展现有文件时,使用其他策略来预分配额外的磁盘空间。这有助于确保扩展文件不会自动导致其分段。新文件不会在现有文件之后立即分配,这也可以防止现有文件的碎片化。

|

||||

|

||||

除了磁盘上数据的实际位置外,EXT4 使用诸如延迟分配的功能策略,以允许文件系统在分配空间之前收集正在写入磁盘的所有数据。这可以提高数据空间将是连续的可能性。

|

||||

|

||||

较旧的EXT文件系统(如 EXT2 和 EXT3)可以作为 EXT4 进行 mount ,以使其性能获得较小的提升。不幸的是,这需要关闭 EXT4 的一些重要的新功能,所以我建议不要这样做。

|

||||

|

||||

自 Fedora 14 以来,EXT4 一直是 Fedora 的默认文件系统。我们可以使用 Fedora 文档中描述的 [procedure ][29] 将EXT3文件系统升级到EXT4,但是由于之前仍然存留d的 EXT3 元数据结构,它的性能仍将受到影响。从 EXT3 升级到 EXT4 的最佳方法是备份目标文件系统分区上的所有数据,使用 **mkfs** 命令将空EXT4文件系统写入分区,然后从备份中恢复所有数据。

|

||||

|

||||

### Inode

|

||||

|

||||

以前描述的 inode 是EXT文件系统中的元数据的关键组件。 图 2 显示了 inode 和存储在硬盘驱动器上的数据之间的关系。 该图是单个文件的目录和 inode,在这种情况下,可能会产生高度碎片。 EXT 文件系统可以积极地减少碎片,所以不太可能会看到有这么多间接数据块或扩展盘的文件。 实际上,如下所示,EXT文件系统中的碎片非常低,所以大多数 inode 只使用一个或两个直接数据指针,也不使用间接指针。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

图 2 :inode 存储有关每个文件的信息,并使 EXT 文件系统能够查找属于它的所有数据。

|

||||

|

||||

inode 不包含文件的名称。通过目录条目访问文件,目录条目本身是文件的名称,并包含指向 inode 的指针。该指针的值是 inode 号。文件系统中的每个 inode 都具有唯一的 ID 号,但同一台计算机上的其他文件系统(甚至相同的硬盘驱动器)中的 inode 可以具有相同的 inode 号。这对[links][30] 存在影响,但是这个讨论超出了本文的范围。

|

||||

|

||||

inod e包含有关该文件的元数据,包括其类型和权限以及其大小。 inode 还包含 15 个指针的空格,用于描述柱面组数据部分中数据块或扩展区的位置和长度。十二个指针提供对数据扩展区的直接访问,并且应该足以处理大多数文件。然而,对于具有重大分段的文件,有必要以间接节点的形式具有一些附加功能。从技术上讲,这些不是真正的节点,所以我在这里使用这个术语“节点”来方便。

|

||||

|

||||

间接节点是文件系统中的正常数据块,它仅用于描述数据而不用于存储元数据,因此可以支持超过 15 个条目。例如,4K 的块大小可以支持 512 个 4 字节间接节点,允许单个文件的 **12(直接)+ 512(间接)= 524** 范围。还支持双重和三重间接节点支持,但我们大多数人不太可能遇到需要许多扩展的文件。

|

||||

|

||||

### 数据碎片

|

||||

|

||||

对于许多较旧的 PC 文件系统,如 FAT(及其所有变体)和 NTFS,碎片一直是导致磁盘性能下降的重大问题。 碎片整理对于其本身和一些专门的整理软件来说已经称为了一项专门的工程,其效果范围从非常有效到仅仅是微乎其微。

|

||||

|

||||

Linux 的扩展文件系统使用数据分配策略,有助于最小化硬盘驱动器上的文件碎片,并在发生碎片时减少碎片的影响。 你可以使用 EXT 文件系统上的 **fsck** 命令检查文件系统的整体碎片。 以下示例检查主工作站的主目录,只有 1.5% 的碎片。 确保使用 **- n** 参数,因为它会阻止 **fsck** 对扫描文件系统采取的任何操作。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

fsck -fn /dev/mapper/vg_01-home

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

我曾经进行过一些理论计算,以确定磁盘碎片整理是否会导致任何明显的性能提升。 虽然我做了一些假设,我使用的磁盘性能数据来自一个新的 300GB 的西部数字硬盘驱动器,具有 2.0ms 的追踪到追踪时间。 此示例中的文件数是在计算当天文件系统中存在的实际数。 我假设有相当大量的碎片文件(约 20%)每天都会被触动。

|

||||

|

||||

| **Total files** | **271,794** |

|

||||

|--|--|

|

||||

| % fragmentation | 5.00% |

|

||||

| Discontinuities | 13,590 |

|

||||

| | |

|

||||

| % fragmented files touched per day | 20% (assume) |

|

||||

| Number of additional seeks | 2,718 |

|

||||

| Average seek time | 10.90 ms |

|

||||

| Total additional seek time per day | 29.63 sec |

|

||||

| | 0.49 min |

|

||||

| | |

|

||||

| Track-to-track seek time | 2.00 ms |

|

||||

| Total additional seek time per day | 5.44 sec |

|

||||

| | 0.091 min |

|

||||

|

||||

表 1: 碎片对磁盘性能的理论影响

|

||||

|

||||

我对每天的全部追加寻道时间进行了两次计算,一次是单磁道寻道时间,这是由于EXT文件分配策略而导致大多数文件的可能性更大的情况,一个是平均搜索时间,我认为这将是一个公平的最坏情况。

|

||||

|

||||

从表 1 可以看出,对绝大多数应用程序而言,碎片化对具有甚至适度性能的硬盘驱动器的现代EXT文件系统的影响将是微乎其微的。您可以将您的环境中的数字插入到您自己的类似电子表格中,以了解你对性能影响的期望。这种类型的计算不一定能够代表实际的性能,但它可以提供一些洞察碎片化及其对系统的理论影响。

|

||||

|

||||

我的大部分分区的碎片率都在 1.5% 左右或 1.6%,我有一个分区有 3.3% 的碎片,但是这是一个大的 128GB 文件系统,具有少于100 个非常大的 ISO 映像文件; 多年来,我不得不扩张分区,因为它已经太满了。

|

||||

|

||||

这并不是说一些应用的环境不需要更多的保证,甚至更少的碎片。 EXT 文件系统可以由有经验和知识的管理员小心调整,管理员可以调整参数以抵消特定的工作负载类型。这个工作可以在文件系统创建的时候或稍后使用 **tune2fs** 命令时完成。每一次调整变化的结果应进行测试,精心的记录和分析,以确保目标环境的最佳性能。在最坏的情况下,如果性能不能提高到期望的水平,则其他文件系统类型可能更适合特定的工作负载。并记住,在单个主机系统上使用混合文件系统类型以匹配放在每个文件系统上的负载是常见的。

|

||||

|

||||

由于大多数 EXT 文件系统的碎片数量较少,因此无需进行碎片整理。在任何情况下,EXT 文件系统都没有安全的碎片整理工具。有几个工具允许你检查单个文件的碎片或文件系统中剩余可用空间的碎片。有一个工具,**e4defrag**,它将对剩余可用空间允许的文件,目录或文件系统进行碎片整理。顾名思义,它只适用于 EXT4 文件系统中的文件,并且它还有一其它的些限制。

|

||||

|

||||

如果有必要在 EXT 文件系统上执行完整的碎片整理,则只有一种方法能够可靠地工作。你必须将文件系统中的所有要进行碎片整理的文件在确保在安全复制到其他位置后将其删除。如果可能,你可以增加文件系统的大小,以帮助减少将来的碎片。然后将文件复制回目标文件系统。但是其实即使这样也不能保证所有文件都被完全碎片整理。

|

||||

|

||||

### 总结

|

||||

|

||||

EXT 文件系统在一些 Linux 发行版本上作为默认文件系统已经超过二十多年了。它们用最少的维护代价提供了稳定性、高可用性、可靠性和其他各种表现。我尝试过一些其它的文件系统但最终都还是回归到 EXT。每一个我在工作中使用到 Linux 的地方都使用到了 EXT 文件系统,同时发现了它们适用于任何主流的负载。毫无疑问,EXT4 文件系统应该被用于大部分的 Linux 文件系统上,除非我们有明显的使用其它文件系统的理由。

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

作者简介:

|

||||

|

||||

David Both - David Both 是一名 Linux 于开源的贡献者,目前居住在北卡罗莱纳州的罗利。他从事 IT 行业有 40 余年并在 IBM 中从事 OS/2 培训约 20 余年。在 IBM 就职期间,他在 1981 年为最早的 IBM PC 写了一个培训课程。他已经为红帽教授了 RHCE 课程,曾在 MCI Worldcom,思科和北卡罗来纳州工作。 他使用 Linux 和开源软件工作了近 20 年。

|

||||

|

||||

-------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://opensource.com/article/17/5/introduction-ext4-filesystem

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[David Both ][a]

|

||||

译者:[chenxinlong](https://github.com/chenxinlong)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:https://opensource.com/users/dboth

|

||||

[1]:https://opensource.com/resources/what-is-linux?src=linux_resource_menu

|

||||

[2]:https://opensource.com/resources/what-are-linux-containers?src=linux_resource_menu

|

||||

[3]:https://developers.redhat.com/promotions/linux-cheatsheet/?intcmp=7016000000127cYAAQ

|

||||

[4]:https://developers.redhat.com/cheat-sheet/advanced-linux-commands-cheatsheet?src=linux_resource_menu&intcmp=7016000000127cYAAQ

|

||||

[5]:https://opensource.com/tags/linux?src=linux_resource_menu

|

||||

[6]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boot_sector

|

||||

[7]:https://opensource.com/article/17/5/introduction-ext4-filesystem?rate=B4QU3W_JYmEKsIKZf5yqMpztt7CRF6uzC0wfNBidEbs

|

||||

[8]:https://www.flickr.com/photos/wwarby/11644168395

|

||||

[9]:https://www.flickr.com/photos/wwarby/11644168395

|

||||

[10]:https://opensource.com/users/jason-baker

|

||||

[11]:https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

|

||||

[12]:https://opensource.com/life/16/10/introduction-linux-filesystems

|

||||

[13]:https://opensource.com/life/15/9/everything-is-a-file

|

||||

[14]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MINIX_file_system

|

||||

[15]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_S._Tanenbaum

|

||||

[16]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MINIX

|

||||

[17]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inode

|

||||

[18]:http://ohm.hgesser.de/sp-ss2012/Intro-MinixFS.pdf

|

||||

[19]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inode_pointer_structure

|

||||

[20]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extended_file_system

|

||||

[21]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R%C3%A9my_Card

|

||||

[22]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ext2

|

||||

[23]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boot_sector

|

||||

[24]:https://opensource.com/article/17/2/linux-boot-and-startup

|

||||

[25]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ext3

|

||||

[26]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Journaling_file_system

|

||||

[27]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ext4

|

||||

[28]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Year_2038_problem

|

||||

[29]:https://docs.fedoraproject.org/en-US/Fedora/14/html/Storage_Administration_Guide/ext4converting.html

|

||||

[30]:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hard_link

|

||||

[31]:https://opensource.com/user/14106/feed

|

||||

[32]:https://opensource.com/article/17/5/introduction-ext4-filesystem#comments

|

||||

[33]:https://opensource.com/users/dboth

|

||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user