mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-03-30 02:40:11 +08:00

Merge pull request #4307 from StdioA/master

Translated 20160406 Let’s Build A Web Server. Part 2

This commit is contained in:

commit

5ac6bdc1ba

sources/tech

translated/tech

@ -1,429 +0,0 @@

|

||||

Translating by StdioA

|

||||

|

||||

Let’s Build A Web Server. Part 2.

|

||||

===================================

|

||||

|

||||

Remember, in Part 1 I asked you a question: “How do you run a Django application, Flask application, and Pyramid application under your freshly minted Web server without making a single change to the server to accommodate all those different Web frameworks?” Read on to find out the answer.

|

||||

|

||||

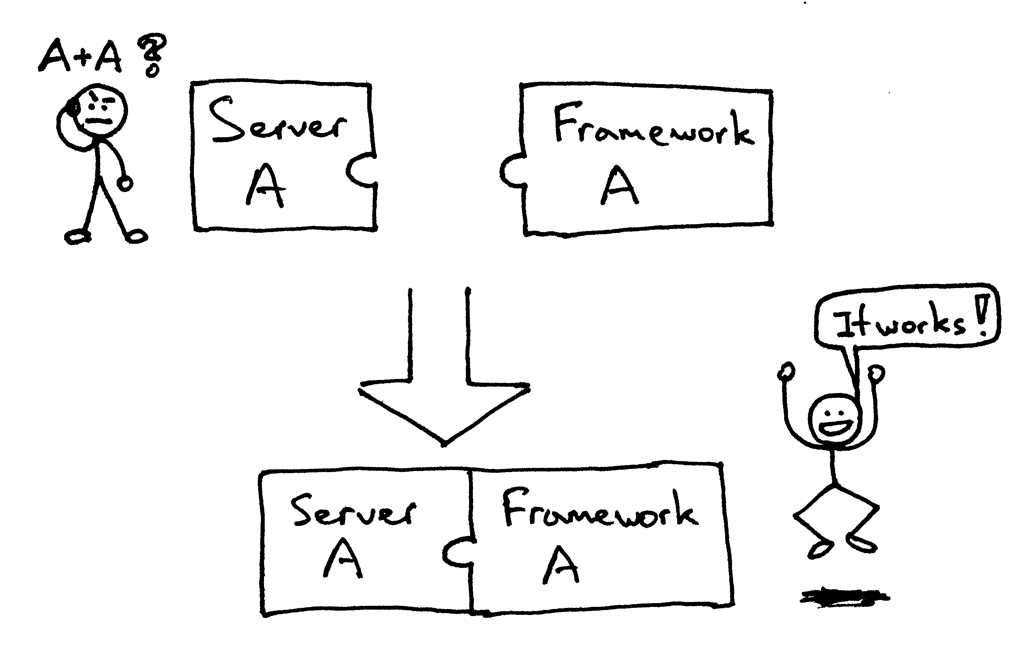

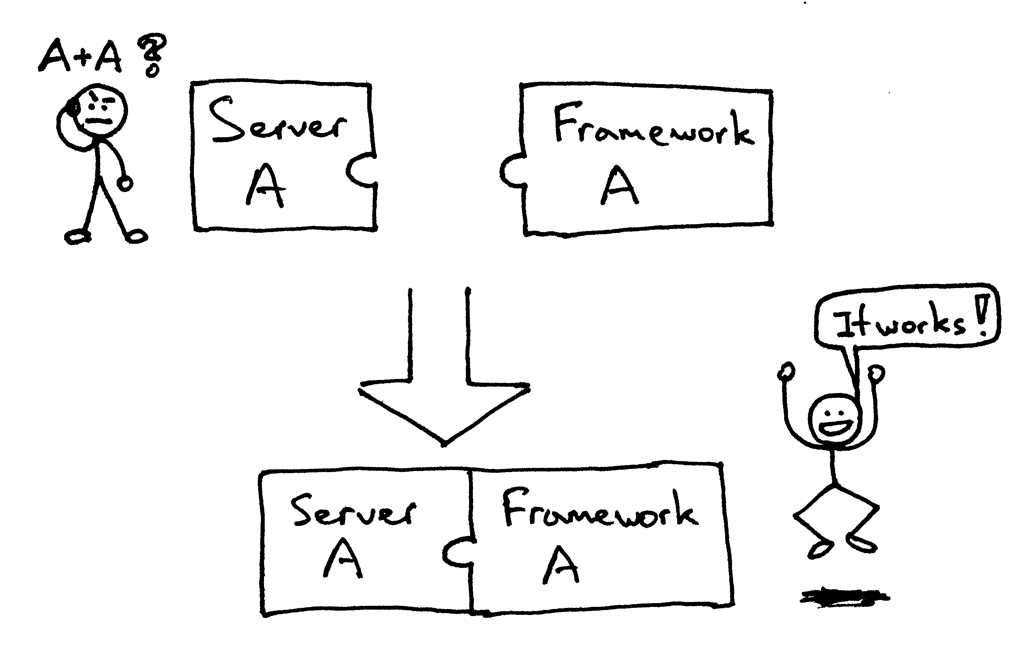

In the past, your choice of a Python Web framework would limit your choice of usable Web servers, and vice versa. If the framework and the server were designed to work together, then you were okay:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

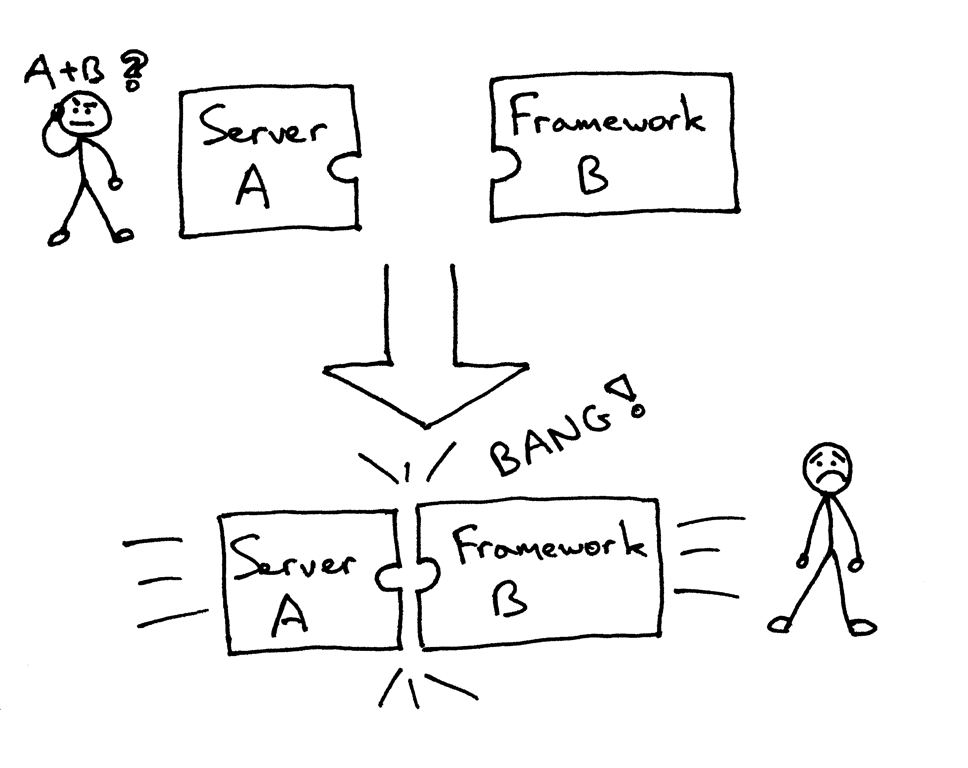

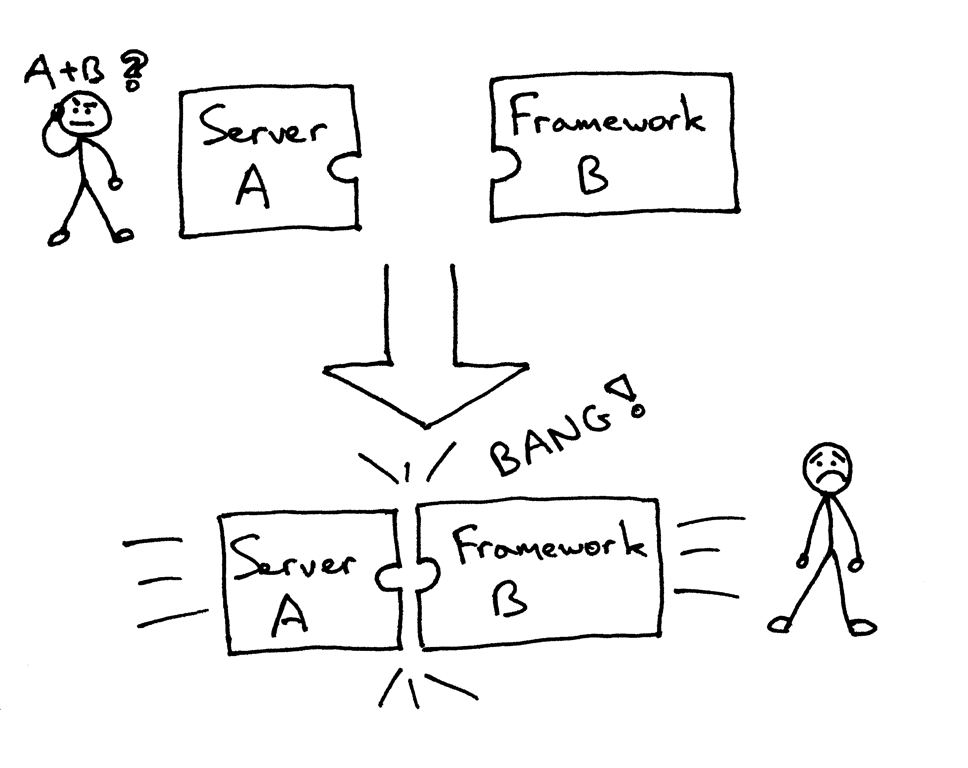

But you could have been faced (and maybe you were) with the following problem when trying to combine a server and a framework that weren’t designed to work together:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Basically you had to use what worked together and not what you might have wanted to use.

|

||||

|

||||

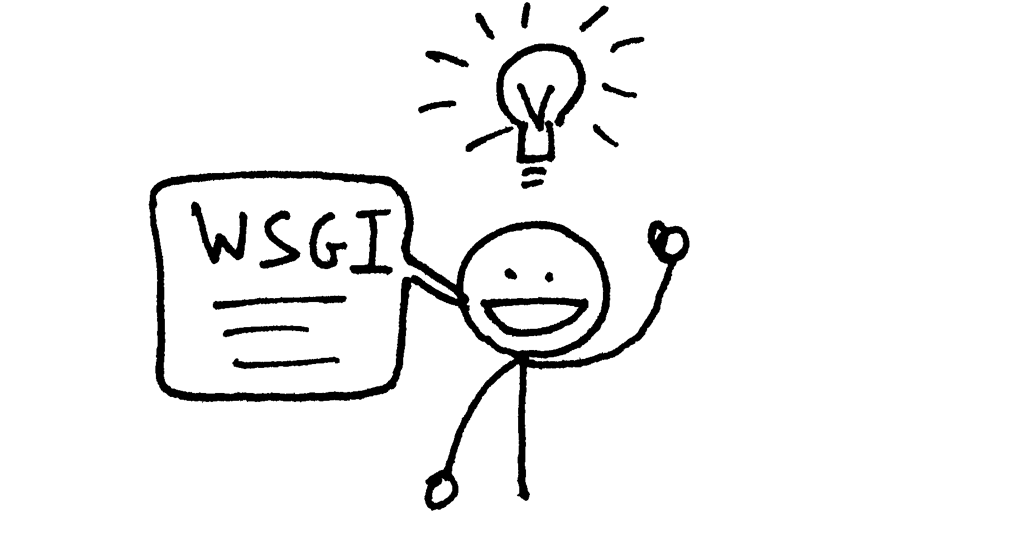

So, how do you then make sure that you can run your Web server with multiple Web frameworks without making code changes either to the Web server or to the Web frameworks? And the answer to that problem became the Python Web Server Gateway Interface (or WSGI for short, pronounced “wizgy”).

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

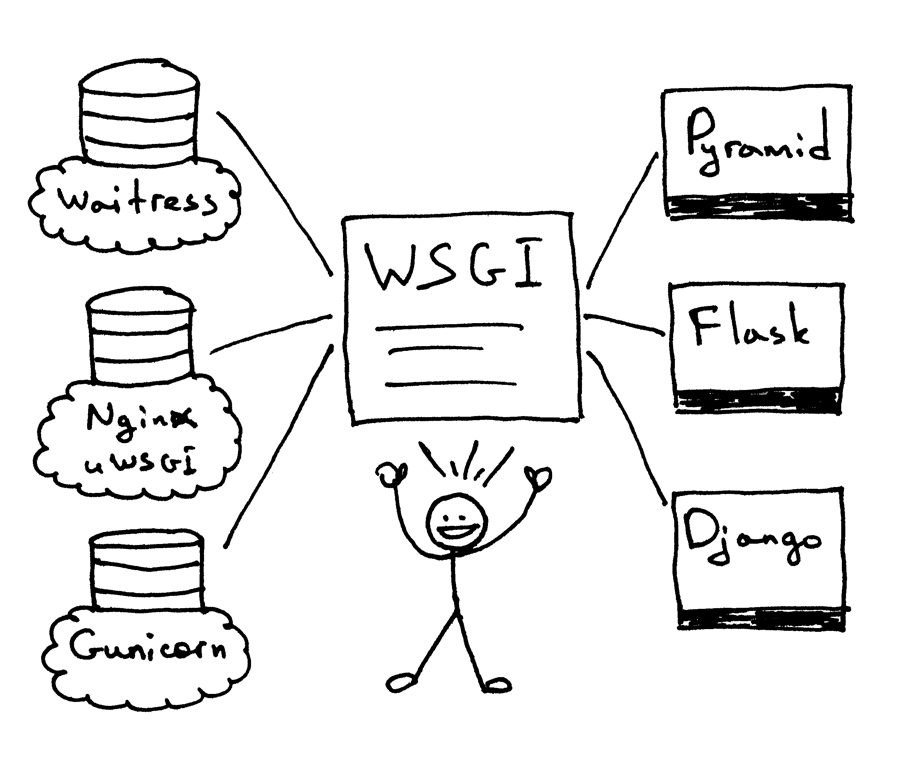

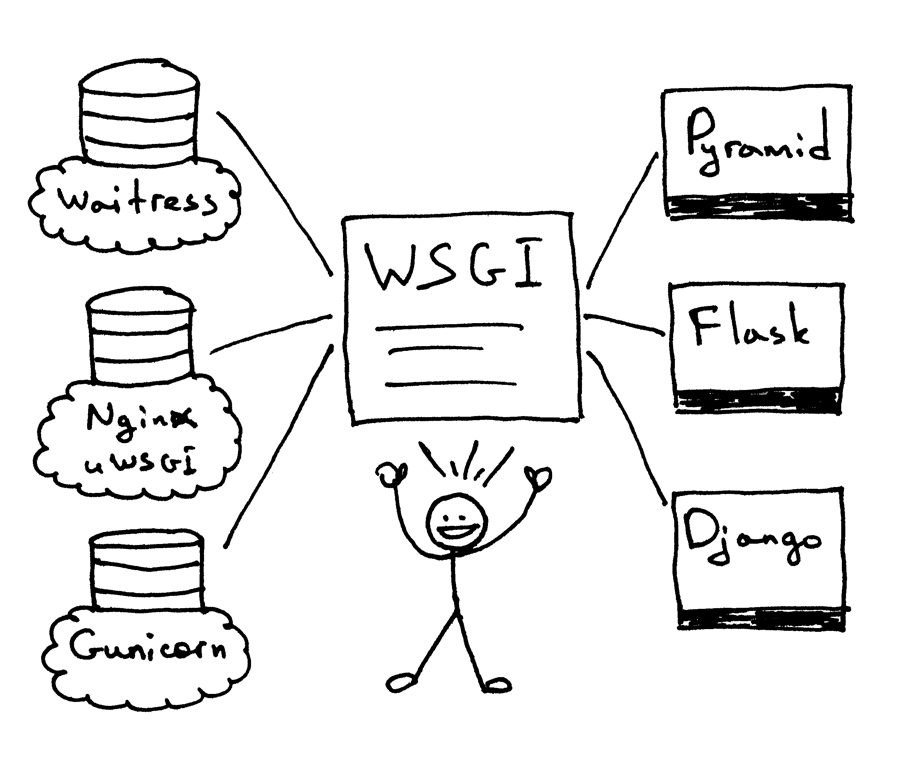

WSGI allowed developers to separate choice of a Web framework from choice of a Web server. Now you can actually mix and match Web servers and Web frameworks and choose a pairing that suits your needs. You can run Django, Flask, or Pyramid, for example, with Gunicorn or Nginx/uWSGI or Waitress. Real mix and match, thanks to the WSGI support in both servers and frameworks:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

So, WSGI is the answer to the question I asked you in Part 1 and repeated at the beginning of this article. Your Web server must implement the server portion of a WSGI interface and all modern Python Web Frameworks already implement the framework side of the WSGI interface, which allows you to use them with your Web server without ever modifying your server’s code to accommodate a particular Web framework.

|

||||

|

||||

Now you know that WSGI support by Web servers and Web frameworks allows you to choose a pairing that suits you, but it is also beneficial to server and framework developers because they can focus on their preferred area of specialization and not step on each other’s toes. Other languages have similar interfaces too: Java, for example, has Servlet API and Ruby has Rack.

|

||||

|

||||

It’s all good, but I bet you are saying: “Show me the code!” Okay, take a look at this pretty minimalistic WSGI server implementation:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

# Tested with Python 2.7.9, Linux & Mac OS X

|

||||

import socket

|

||||

import StringIO

|

||||

import sys

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

class WSGIServer(object):

|

||||

|

||||

address_family = socket.AF_INET

|

||||

socket_type = socket.SOCK_STREAM

|

||||

request_queue_size = 1

|

||||

|

||||

def __init__(self, server_address):

|

||||

# Create a listening socket

|

||||

self.listen_socket = listen_socket = socket.socket(

|

||||

self.address_family,

|

||||

self.socket_type

|

||||

)

|

||||

# Allow to reuse the same address

|

||||

listen_socket.setsockopt(socket.SOL_SOCKET, socket.SO_REUSEADDR, 1)

|

||||

# Bind

|

||||

listen_socket.bind(server_address)

|

||||

# Activate

|

||||

listen_socket.listen(self.request_queue_size)

|

||||

# Get server host name and port

|

||||

host, port = self.listen_socket.getsockname()[:2]

|

||||

self.server_name = socket.getfqdn(host)

|

||||

self.server_port = port

|

||||

# Return headers set by Web framework/Web application

|

||||

self.headers_set = []

|

||||

|

||||

def set_app(self, application):

|

||||

self.application = application

|

||||

|

||||

def serve_forever(self):

|

||||

listen_socket = self.listen_socket

|

||||

while True:

|

||||

# New client connection

|

||||

self.client_connection, client_address = listen_socket.accept()

|

||||

# Handle one request and close the client connection. Then

|

||||

# loop over to wait for another client connection

|

||||

self.handle_one_request()

|

||||

|

||||

def handle_one_request(self):

|

||||

self.request_data = request_data = self.client_connection.recv(1024)

|

||||

# Print formatted request data a la 'curl -v'

|

||||

print(''.join(

|

||||

'< {line}\n'.format(line=line)

|

||||

for line in request_data.splitlines()

|

||||

))

|

||||

|

||||

self.parse_request(request_data)

|

||||

|

||||

# Construct environment dictionary using request data

|

||||

env = self.get_environ()

|

||||

|

||||

# It's time to call our application callable and get

|

||||

# back a result that will become HTTP response body

|

||||

result = self.application(env, self.start_response)

|

||||

|

||||

# Construct a response and send it back to the client

|

||||

self.finish_response(result)

|

||||

|

||||

def parse_request(self, text):

|

||||

request_line = text.splitlines()[0]

|

||||

request_line = request_line.rstrip('\r\n')

|

||||

# Break down the request line into components

|

||||

(self.request_method, # GET

|

||||

self.path, # /hello

|

||||

self.request_version # HTTP/1.1

|

||||

) = request_line.split()

|

||||

|

||||

def get_environ(self):

|

||||

env = {}

|

||||

# The following code snippet does not follow PEP8 conventions

|

||||

# but it's formatted the way it is for demonstration purposes

|

||||

# to emphasize the required variables and their values

|

||||

#

|

||||

# Required WSGI variables

|

||||

env['wsgi.version'] = (1, 0)

|

||||

env['wsgi.url_scheme'] = 'http'

|

||||

env['wsgi.input'] = StringIO.StringIO(self.request_data)

|

||||

env['wsgi.errors'] = sys.stderr

|

||||

env['wsgi.multithread'] = False

|

||||

env['wsgi.multiprocess'] = False

|

||||

env['wsgi.run_once'] = False

|

||||

# Required CGI variables

|

||||

env['REQUEST_METHOD'] = self.request_method # GET

|

||||

env['PATH_INFO'] = self.path # /hello

|

||||

env['SERVER_NAME'] = self.server_name # localhost

|

||||

env['SERVER_PORT'] = str(self.server_port) # 8888

|

||||

return env

|

||||

|

||||

def start_response(self, status, response_headers, exc_info=None):

|

||||

# Add necessary server headers

|

||||

server_headers = [

|

||||

('Date', 'Tue, 31 Mar 2015 12:54:48 GMT'),

|

||||

('Server', 'WSGIServer 0.2'),

|

||||

]

|

||||

self.headers_set = [status, response_headers + server_headers]

|

||||

# To adhere to WSGI specification the start_response must return

|

||||

# a 'write' callable. We simplicity's sake we'll ignore that detail

|

||||

# for now.

|

||||

# return self.finish_response

|

||||

|

||||

def finish_response(self, result):

|

||||

try:

|

||||

status, response_headers = self.headers_set

|

||||

response = 'HTTP/1.1 {status}\r\n'.format(status=status)

|

||||

for header in response_headers:

|

||||

response += '{0}: {1}\r\n'.format(*header)

|

||||

response += '\r\n'

|

||||

for data in result:

|

||||

response += data

|

||||

# Print formatted response data a la 'curl -v'

|

||||

print(''.join(

|

||||

'> {line}\n'.format(line=line)

|

||||

for line in response.splitlines()

|

||||

))

|

||||

self.client_connection.sendall(response)

|

||||

finally:

|

||||

self.client_connection.close()

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

SERVER_ADDRESS = (HOST, PORT) = '', 8888

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

def make_server(server_address, application):

|

||||

server = WSGIServer(server_address)

|

||||

server.set_app(application)

|

||||

return server

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

if __name__ == '__main__':

|

||||

if len(sys.argv) < 2:

|

||||

sys.exit('Provide a WSGI application object as module:callable')

|

||||

app_path = sys.argv[1]

|

||||

module, application = app_path.split(':')

|

||||

module = __import__(module)

|

||||

application = getattr(module, application)

|

||||

httpd = make_server(SERVER_ADDRESS, application)

|

||||

print('WSGIServer: Serving HTTP on port {port} ...\n'.format(port=PORT))

|

||||

httpd.serve_forever()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

It’s definitely bigger than the server code in Part 1, but it’s also small enough (just under 150 lines) for you to understand without getting bogged down in details. The above server also does more - it can run your basic Web application written with your beloved Web framework, be it Pyramid, Flask, Django, or some other Python WSGI framework.

|

||||

|

||||

Don’t believe me? Try it and see for yourself. Save the above code as webserver2.py or download it directly from GitHub. If you try to run it without any parameters it’s going to complain and exit.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

$ python webserver2.py

|

||||

Provide a WSGI application object as module:callable

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

It really wants to serve your Web application and that’s where the fun begins. To run the server the only thing you need installed is Python. But to run applications written with Pyramid, Flask, and Django you need to install those frameworks first. Let’s install all three of them. My preferred method is by using virtualenv. Just follow the steps below to create and activate a virtual environment and then install all three Web frameworks.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

$ [sudo] pip install virtualenv

|

||||

$ mkdir ~/envs

|

||||

$ virtualenv ~/envs/lsbaws/

|

||||

$ cd ~/envs/lsbaws/

|

||||

$ ls

|

||||

bin include lib

|

||||

$ source bin/activate

|

||||

(lsbaws) $ pip install pyramid

|

||||

(lsbaws) $ pip install flask

|

||||

(lsbaws) $ pip install django

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

At this point you need to create a Web application. Let’s start with Pyramid first. Save the following code as pyramidapp.py to the same directory where you saved webserver2.py or download the file directly from GitHub:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

from pyramid.config import Configurator

|

||||

from pyramid.response import Response

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

def hello_world(request):

|

||||

return Response(

|

||||

'Hello world from Pyramid!\n',

|

||||

content_type='text/plain',

|

||||

)

|

||||

|

||||

config = Configurator()

|

||||

config.add_route('hello', '/hello')

|

||||

config.add_view(hello_world, route_name='hello')

|

||||

app = config.make_wsgi_app()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Now you’re ready to serve your Pyramid application with your very own Web server:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

(lsbaws) $ python webserver2.py pyramidapp:app

|

||||

WSGIServer: Serving HTTP on port 8888 ...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

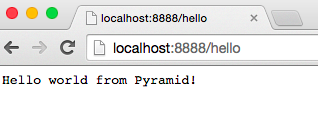

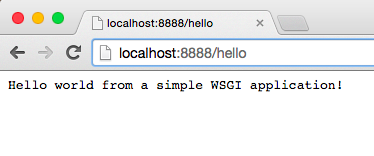

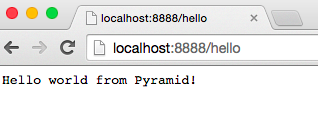

You just told your server to load the ‘app’ callable from the python module ‘pyramidapp’ Your server is now ready to take requests and forward them to your Pyramid application. The application only handles one route now: the /hello route. Type http://localhost:8888/hello address into your browser, press Enter, and observe the result:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

You can also test the server on the command line using the ‘curl’ utility:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

$ curl -v http://localhost:8888/hello

|

||||

...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Check what the server and curl prints to standard output.

|

||||

|

||||

Now onto Flask. Let’s follow the same steps.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

from flask import Flask

|

||||

from flask import Response

|

||||

flask_app = Flask('flaskapp')

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@flask_app.route('/hello')

|

||||

def hello_world():

|

||||

return Response(

|

||||

'Hello world from Flask!\n',

|

||||

mimetype='text/plain'

|

||||

)

|

||||

|

||||

app = flask_app.wsgi_app

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Save the above code as flaskapp.py or download it from GitHub and run the server as:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

(lsbaws) $ python webserver2.py flaskapp:app

|

||||

WSGIServer: Serving HTTP on port 8888 ...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

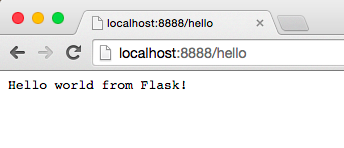

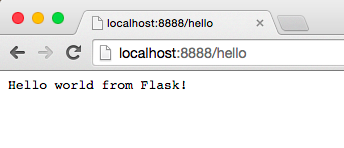

Now type in the http://localhost:8888/hello into your browser and press Enter:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Again, try ‘curl’ and see for yourself that the server returns a message generated by the Flask application:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

$ curl -v http://localhost:8888/hello

|

||||

...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Can the server also handle a Django application? Try it out! It’s a little bit more involved, though, and I would recommend cloning the whole repo and use djangoapp.py, which is part of the GitHub repository. Here is the source code which basically adds the Django ‘helloworld’ project (pre-created using Django’s django-admin.py startproject command) to the current Python path and then imports the project’s WSGI application.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

import sys

|

||||

sys.path.insert(0, './helloworld')

|

||||

from helloworld import wsgi

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

app = wsgi.application

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Save the above code as djangoapp.py and run the Django application with your Web server:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

(lsbaws) $ python webserver2.py djangoapp:app

|

||||

WSGIServer: Serving HTTP on port 8888 ...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

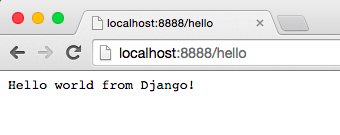

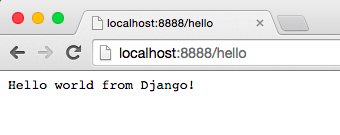

Type in the following address and press Enter:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

And as you’ve already done a couple of times before, you can test it on the command line, too, and confirm that it’s the Django application that handles your requests this time around:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

$ curl -v http://localhost:8888/hello

|

||||

...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Did you try it? Did you make sure the server works with those three frameworks? If not, then please do so. Reading is important, but this series is about rebuilding and that means you need to get your hands dirty. Go and try it. I will wait for you, don’t worry. No seriously, you must try it and, better yet, retype everything yourself and make sure that it works as expected.

|

||||

|

||||

Okay, you’ve experienced the power of WSGI: it allows you to mix and match your Web servers and Web frameworks. WSGI provides a minimal interface between Python Web servers and Python Web Frameworks. It’s very simple and it’s easy to implement on both the server and the framework side. The following code snippet shows the server and the framework side of the interface:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

def run_application(application):

|

||||

"""Server code."""

|

||||

# This is where an application/framework stores

|

||||

# an HTTP status and HTTP response headers for the server

|

||||

# to transmit to the client

|

||||

headers_set = []

|

||||

# Environment dictionary with WSGI/CGI variables

|

||||

environ = {}

|

||||

|

||||

def start_response(status, response_headers, exc_info=None):

|

||||

headers_set[:] = [status, response_headers]

|

||||

|

||||

# Server invokes the ‘application' callable and gets back the

|

||||

# response body

|

||||

result = application(environ, start_response)

|

||||

# Server builds an HTTP response and transmits it to the client

|

||||

…

|

||||

|

||||

def app(environ, start_response):

|

||||

"""A barebones WSGI app."""

|

||||

start_response('200 OK', [('Content-Type', 'text/plain')])

|

||||

return ['Hello world!']

|

||||

|

||||

run_application(app)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

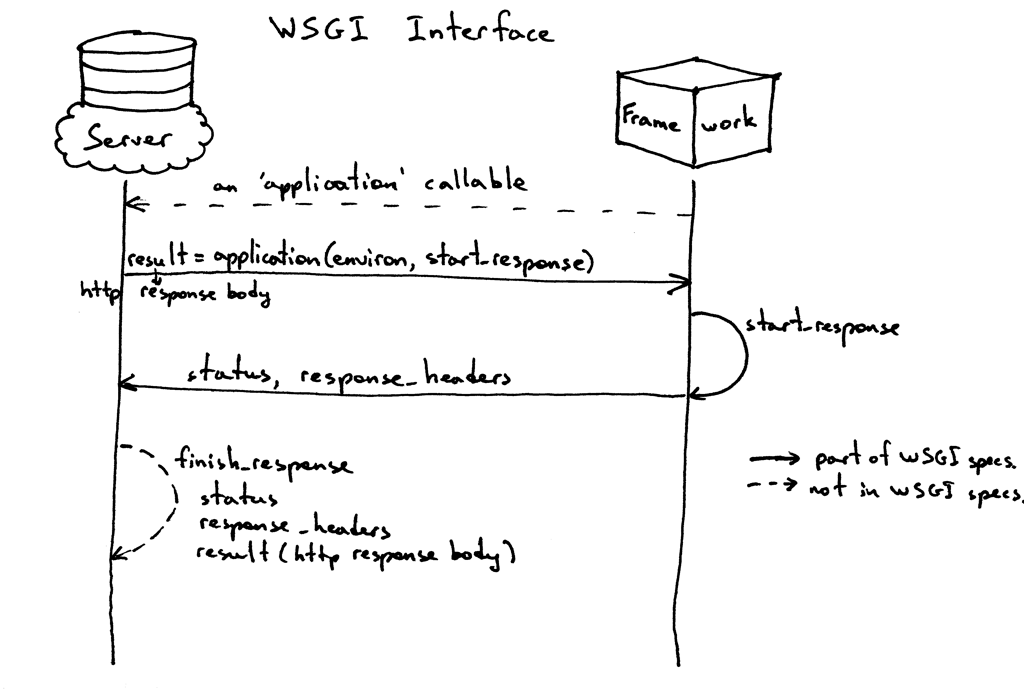

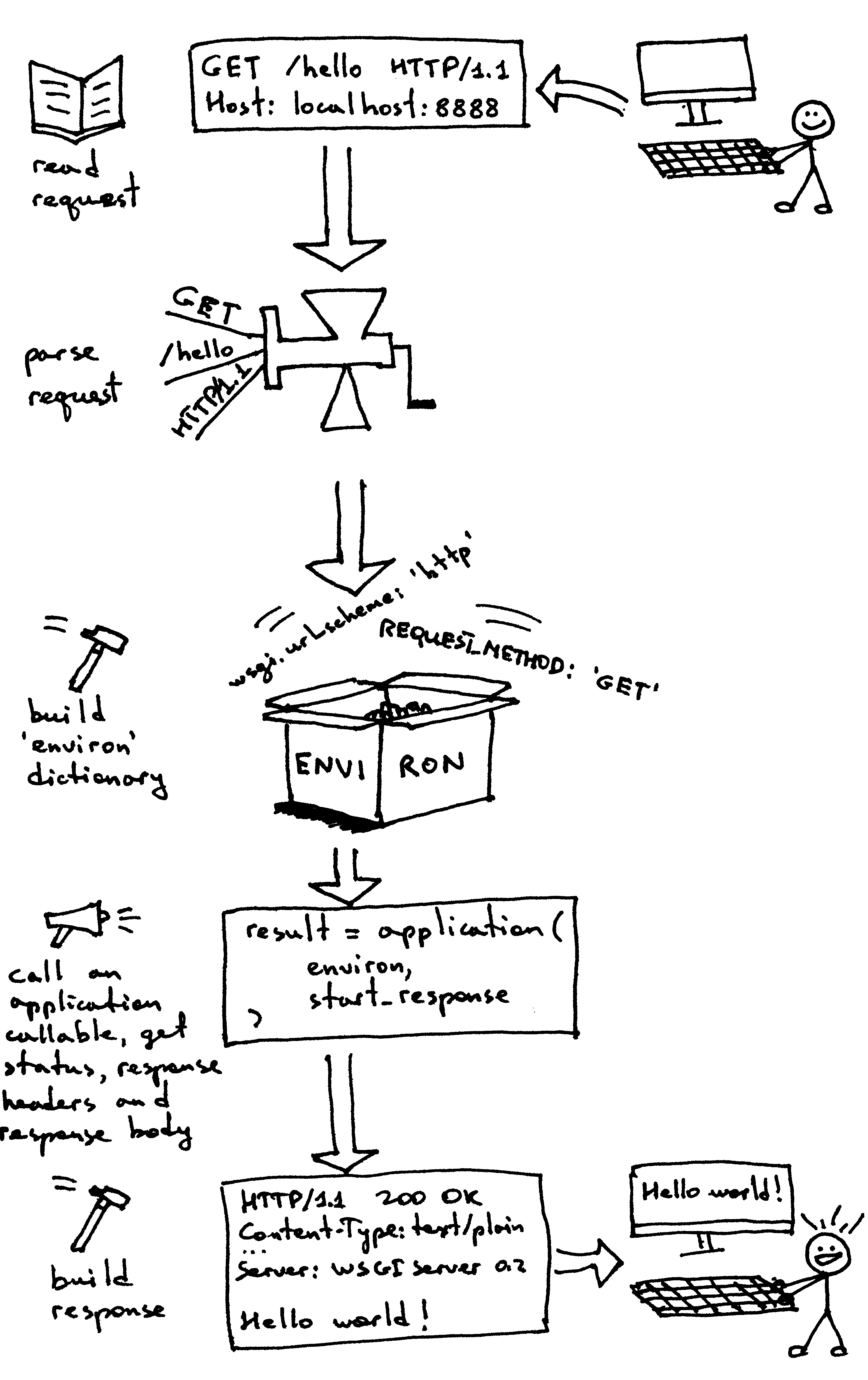

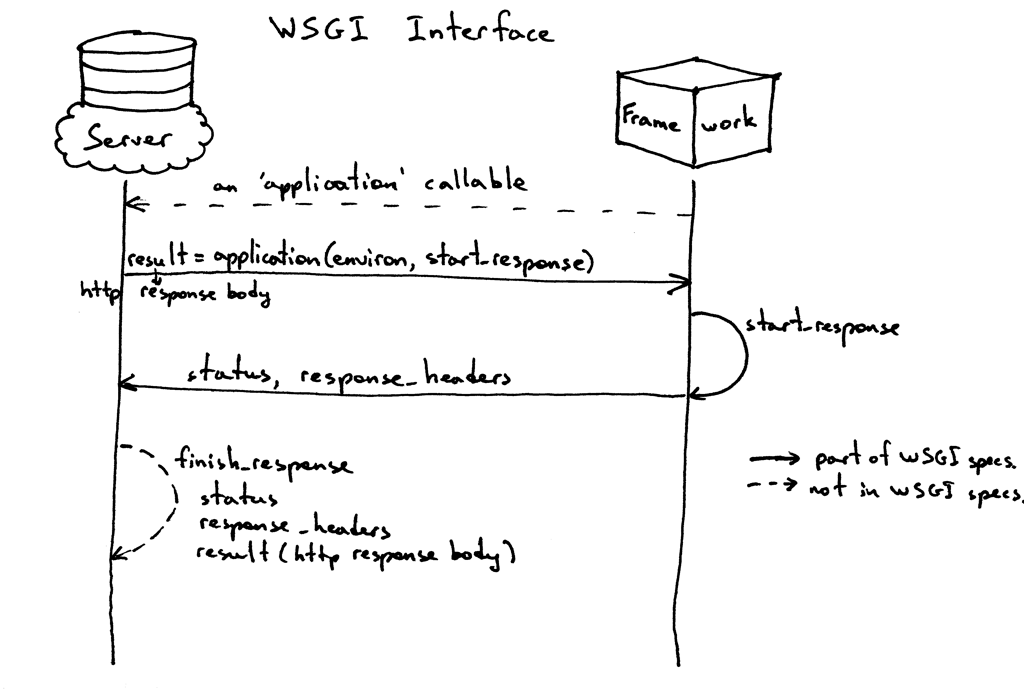

Here is how it works:

|

||||

|

||||

1. The framework provides an ‘application’ callable (The WSGI specification doesn’t prescribe how that should be implemented)

|

||||

2. The server invokes the ‘application’ callable for each request it receives from an HTTP client. It passes a dictionary ‘environ’ containing WSGI/CGI variables and a ‘start_response’ callable as arguments to the ‘application’ callable.

|

||||

3. The framework/application generates an HTTP status and HTTP response headers and passes them to the ‘start_response’ callable for the server to store them. The framework/application also returns a response body.

|

||||

4. The server combines the status, the response headers, and the response body into an HTTP response and transmits it to the client (This step is not part of the specification but it’s the next logical step in the flow and I added it for clarity)

|

||||

|

||||

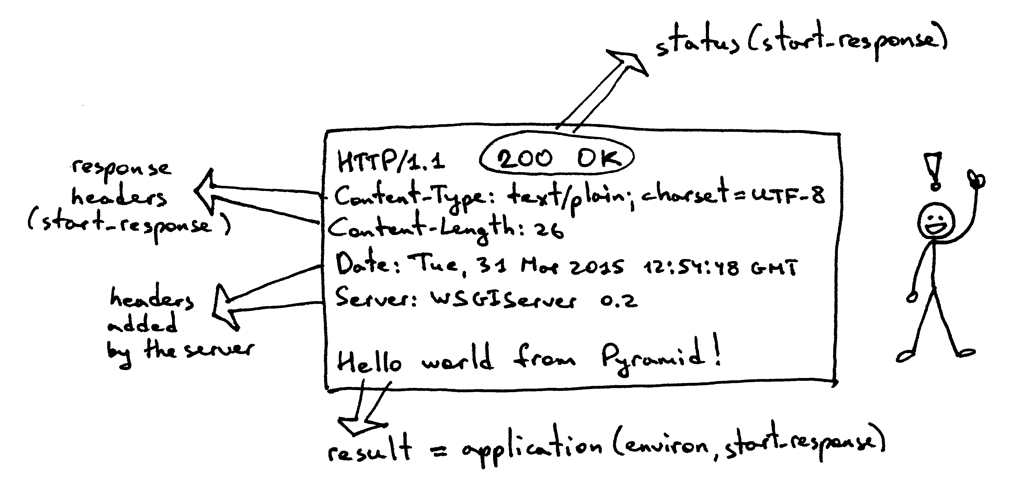

And here is a visual representation of the interface:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

So far, you’ve seen the Pyramid, Flask, and Django Web applications and you’ve seen the server code that implements the server side of the WSGI specification. You’ve even seen the barebones WSGI application code snippet that doesn’t use any framework.

|

||||

|

||||

The thing is that when you write a Web application using one of those frameworks you work at a higher level and don’t work with WSGI directly, but I know you’re curious about the framework side of the WSGI interface, too because you’re reading this article. So, let’s create a minimalistic WSGI Web application/Web framework without using Pyramid, Flask, or Django and run it with your server:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

def app(environ, start_response):

|

||||

"""A barebones WSGI application.

|

||||

|

||||

This is a starting point for your own Web framework :)

|

||||

"""

|

||||

status = '200 OK'

|

||||

response_headers = [('Content-Type', 'text/plain')]

|

||||

start_response(status, response_headers)

|

||||

return ['Hello world from a simple WSGI application!\n']

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Again, save the above code in wsgiapp.py file or download it from GitHub directly and run the application under your Web server as:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

(lsbaws) $ python webserver2.py wsgiapp:app

|

||||

WSGIServer: Serving HTTP on port 8888 ...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

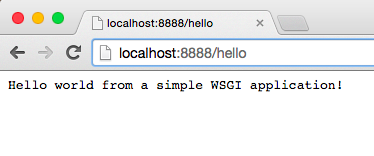

Type in the following address and press Enter. This is the result you should see:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

You just wrote your very own minimalistic WSGI Web framework while learning about how to create a Web server! Outrageous.

|

||||

|

||||

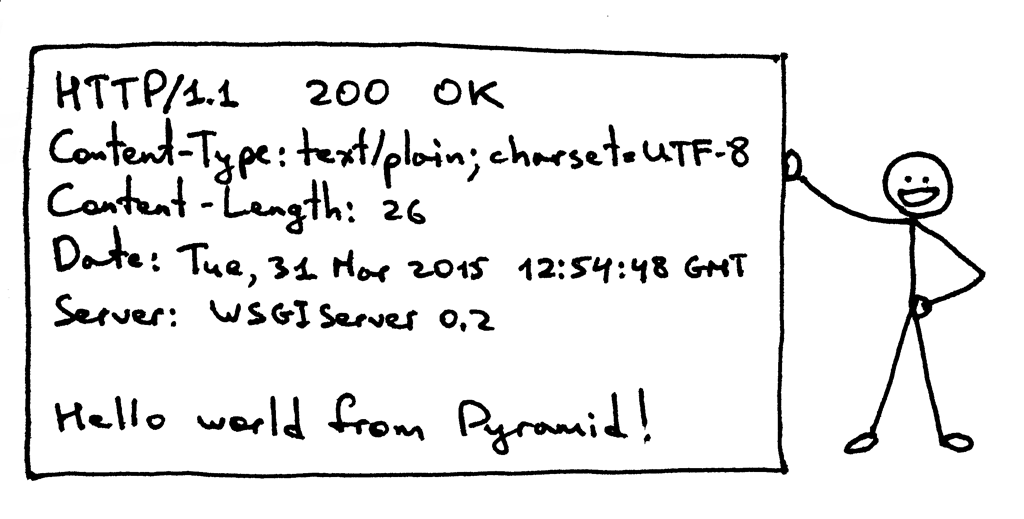

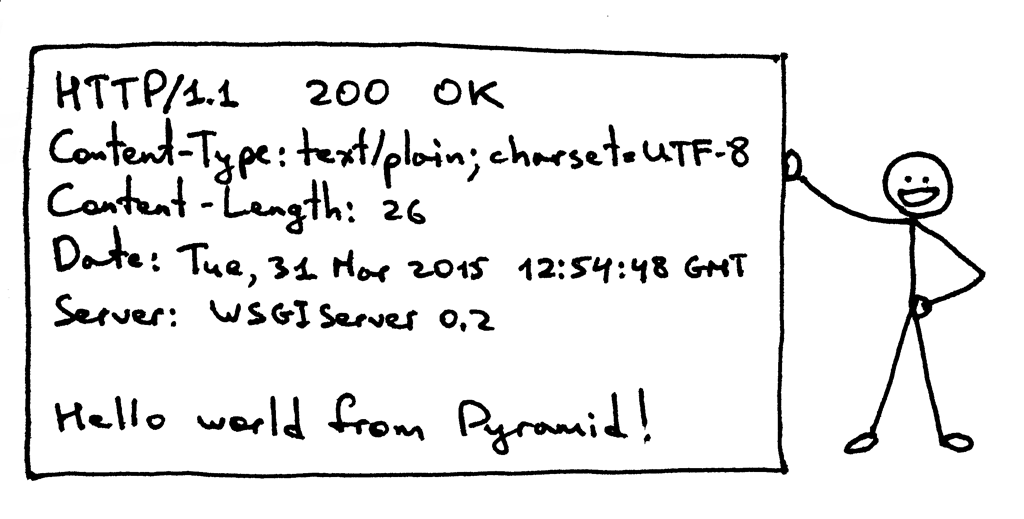

Now, let’s get back to what the server transmits to the client. Here is the HTTP response the server generates when you call your Pyramid application using an HTTP client:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The response has some familiar parts that you saw in Part 1 but it also has something new. It has, for example, four HTTP headers that you haven’t seen before: Content-Type, Content-Length, Date, and Server. Those are the headers that a response from a Web server generally should have. None of them are strictly required, though. The purpose of the headers is to transmit additional information about the HTTP request/response.

|

||||

|

||||

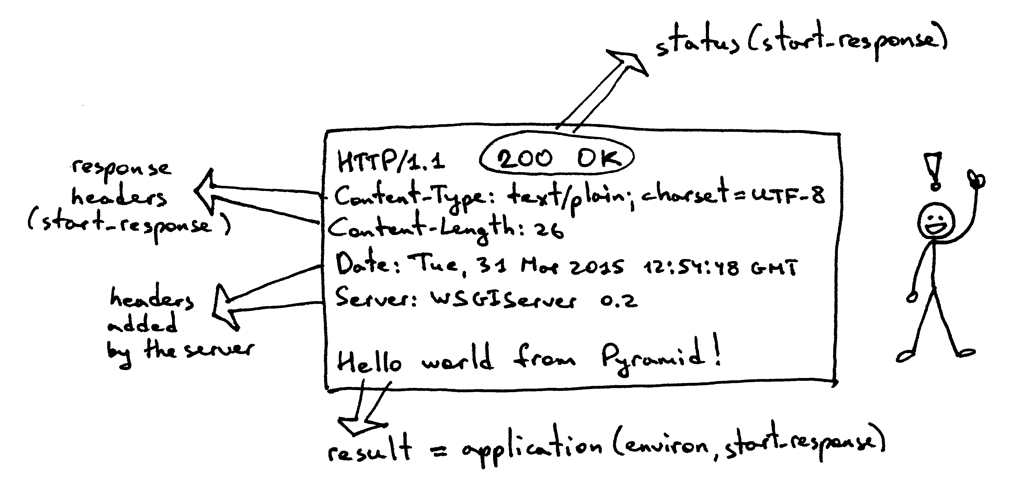

Now that you know more about the WSGI interface, here is the same HTTP response with some more information about what parts produced it:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

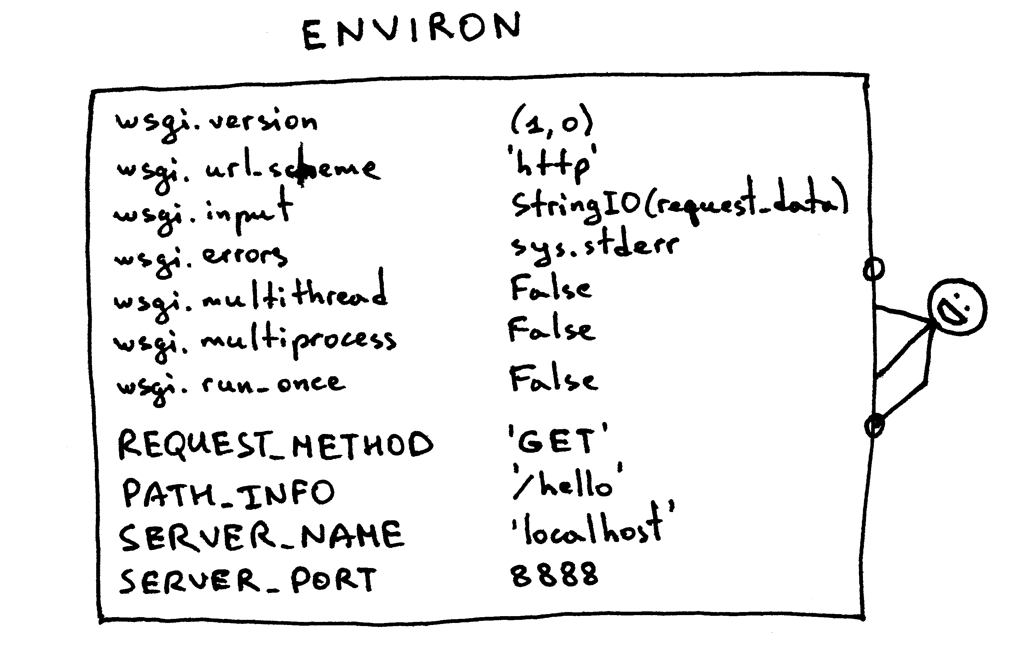

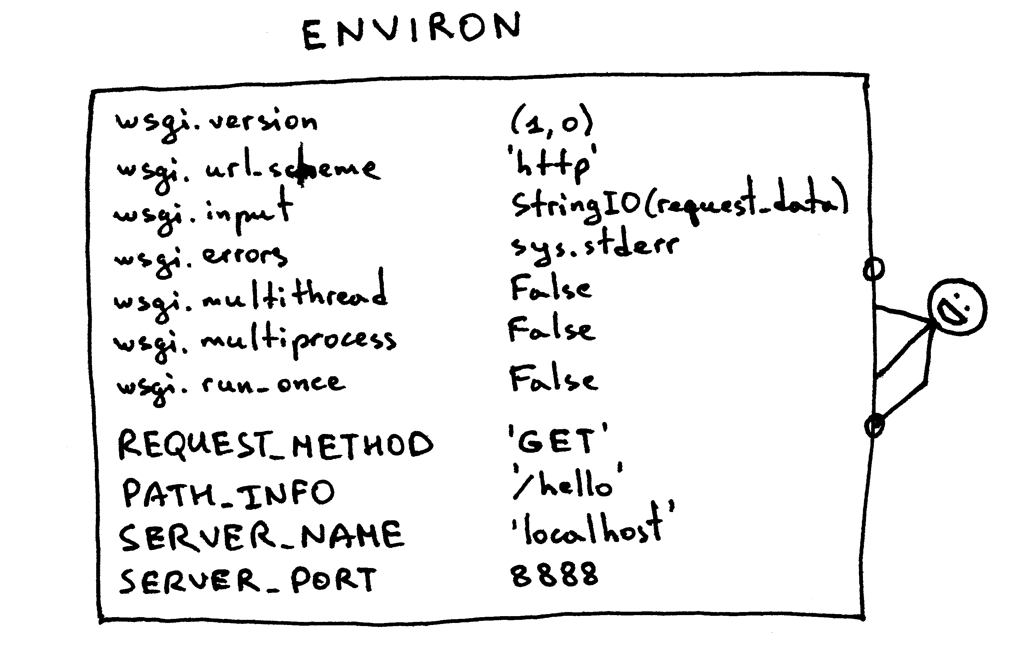

I haven’t said anything about the ‘environ’ dictionary yet, but basically it’s a Python dictionary that must contain certain WSGI and CGI variables prescribed by the WSGI specification. The server takes the values for the dictionary from the HTTP request after parsing the request. This is what the contents of the dictionary look like:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

A Web framework uses the information from that dictionary to decide which view to use based on the specified route, request method etc., where to read the request body from and where to write errors, if any.

|

||||

|

||||

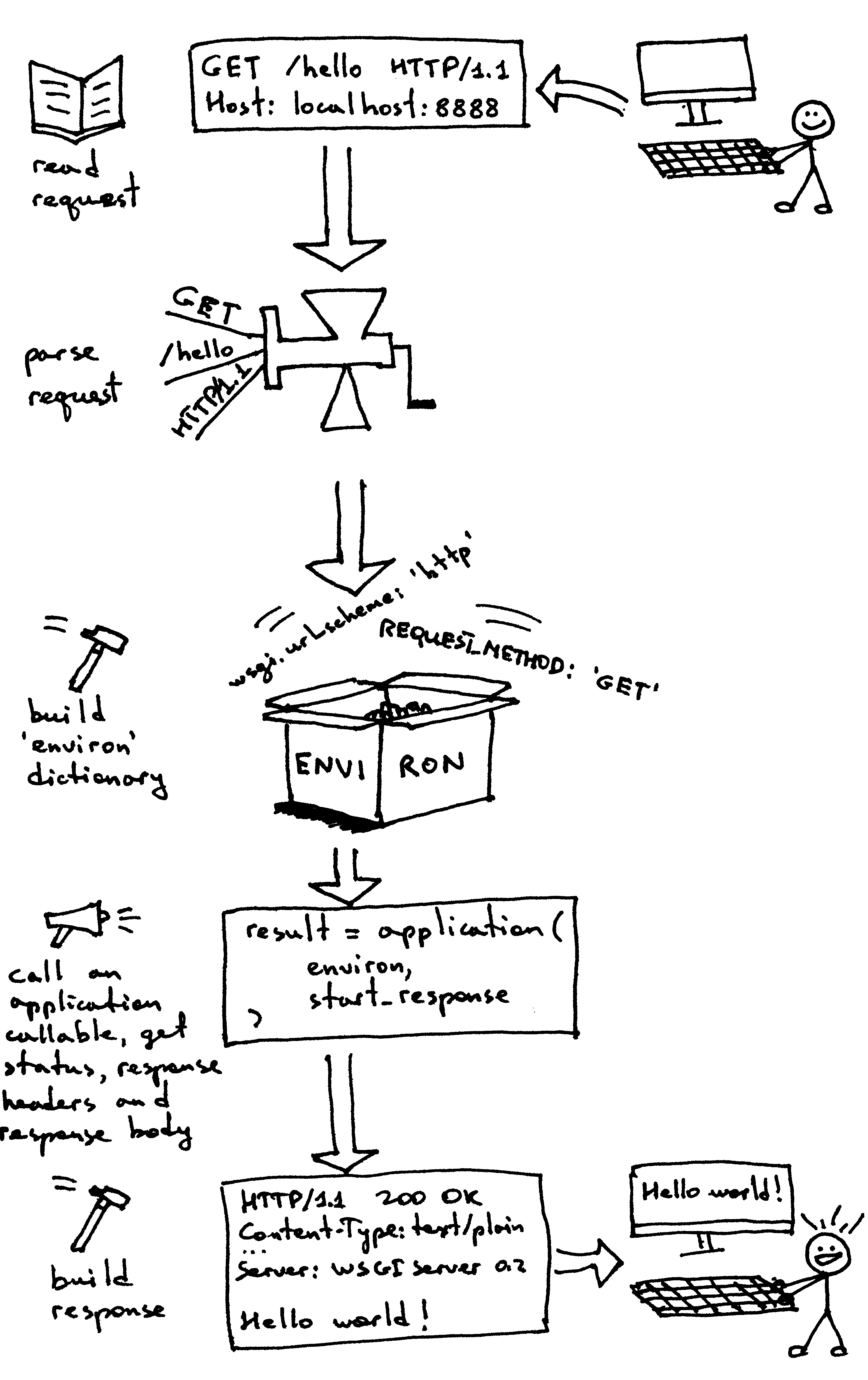

By now you’ve created your own WSGI Web server and you’ve made Web applications written with different Web frameworks. And, you’ve also created your barebones Web application/Web framework along the way. It’s been a heck of a journey. Let’s recap what your WSGI Web server has to do to serve requests aimed at a WSGI application:

|

||||

|

||||

- First, the server starts and loads an ‘application’ callable provided by your Web framework/application

|

||||

- Then, the server reads a request

|

||||

- Then, the server parses it

|

||||

- Then, it builds an ‘environ’ dictionary using the request data

|

||||

- Then, it calls the ‘application’ callable with the ‘environ’ dictionary and a ‘start_response’ callable as parameters and gets back a response body.

|

||||

- Then, the server constructs an HTTP response using the data returned by the call to the ‘application’ object and the status and response headers set by the ‘start_response’ callable.

|

||||

- And finally, the server transmits the HTTP response back to the client

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

That’s about all there is to it. You now have a working WSGI server that can serve basic Web applications written with WSGI compliant Web frameworks like Django, Flask, Pyramid, or your very own WSGI framework. The best part is that the server can be used with multiple Web frameworks without any changes to the server code base. Not bad at all.

|

||||

|

||||

Before you go, here is another question for you to think about, “How do you make your server handle more than one request at a time?”

|

||||

|

||||

Stay tuned and I will show you a way to do that in Part 3. Cheers!

|

||||

|

||||

BTW, I’m writing a book “Let’s Build A Web Server: First Steps” that explains how to write a basic web server from scratch and goes into more detail on topics I just covered. Subscribe to the mailing list to get the latest updates about the book and the release date.

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://ruslanspivak.com/lsbaws-part2/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Ruslan][a]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]: https://github.com/rspivak/

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

424

translated/tech/20160406 Let’s Build A Web Server. Part 2.md

Normal file

424

translated/tech/20160406 Let’s Build A Web Server. Part 2.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,424 @@

|

||||

搭个 Web 服务器(二)

|

||||

===================================

|

||||

|

||||

在第一部分中,我提出了一个问题:“你要如何在不对程序做任何改动的情况下,在你刚刚搭建起来的 Web 服务器上适配 Django, Flask 或 Pyramid 应用呢?”我们可以从这一篇中找到答案。

|

||||

|

||||

曾几何时,你对 Python Web 框架种类作出的选择会对可用的 Web 服务器类型造成限制,反之亦然。如果框架及服务器在设计层面可以一起工作(相互适配),那么一切正常:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

但你可能正面对着(或者曾经面对过)尝试将一对无法适配的框架和服务器搭配在一起的问题:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

基本上,你需要选择那些能够一起工作的框架和服务器,而不能选择你想用的那些。

|

||||

|

||||

所以,你该如何确保在不对代码做任何更改的情况下,让你的 Web 服务器和多个不同的 Web 框架一同工作呢?这个问题的答案,就是 Python Web 服务器网关接口(缩写为 WSGI,念做“wizgy”)。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

WSGI 允许开发者互不干扰地选择 Web 框架及 Web 服务器的类型。现在,你可以真正将 Web 服务器及框架任意搭配,然后选出你最中意的那对组合。比如,你可以使用 Django,Flask 或者 Pyramid,与 Gunicorn,Nginx/uWSGI 或 Waitress 进行结合。感谢 WSGI 同时对服务器与框架的支持,我们可以真正随意选择它们的搭配了。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

所以,WSGI 就是我在第一部分中提出,又在本文开头重复了一遍的那个问题的答案。你的 Web 服务器必须实现 WSGI 接口的服务器部分,而现代的 Python Web 框架均已实现了 WSGI 接口的框架部分,这使得你可以直接在 Web 服务器中使用任意框架,而不需要更改任何服务器代码,以对特定的 Web 框架实现兼容。

|

||||

|

||||

现在,你一个知道 Web 服务器及 Web 框架对 WSGI 的支持使得你可以选择最合适的一对来使用,而且它对服务器和框架的开发者依然有益,因为他们只需专注于他们擅长的部分来进行开发,而不需要触及另一部分的代码。其它语言也拥有类似的接口,比如:Java 拥有 Servlet API,而 Ruby 拥有 Rack.

|

||||

|

||||

这些理论都不错,但是我打赌你在说:“给我看代码!” 那好,我们来看看下面这个很小的 WSGI 服务器实现:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

# 使用 Python 2.7.9,在 Linux 及 Mac OS X 下测试通过

|

||||

import socket

|

||||

import StringIO

|

||||

import sys

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

class WSGIServer(object):

|

||||

|

||||

address_family = socket.AF_INET

|

||||

socket_type = socket.SOCK_STREAM

|

||||

request_queue_size = 1

|

||||

|

||||

def __init__(self, server_address):

|

||||

# Create a listening socket

|

||||

self.listen_socket = listen_socket = socket.socket(

|

||||

self.address_family,

|

||||

self.socket_type

|

||||

)

|

||||

# 允许复用同一地址

|

||||

listen_socket.setsockopt(socket.SOL_SOCKET, socket.SO_REUSEADDR, 1)

|

||||

# 绑定地址

|

||||

listen_socket.bind(server_address)

|

||||

# 激活套接字

|

||||

listen_socket.listen(self.request_queue_size)

|

||||

# 获取主机名称及端口

|

||||

host, port = self.listen_socket.getsockname()[:2]

|

||||

self.server_name = socket.getfqdn(host)

|

||||

self.server_port = port

|

||||

# 由 Web 框架/应用设定的响应头部字段

|

||||

self.headers_set = []

|

||||

|

||||

def set_app(self, application):

|

||||

self.application = application

|

||||

|

||||

def serve_forever(self):

|

||||

listen_socket = self.listen_socket

|

||||

while True:

|

||||

# 获取新的客户端连接

|

||||

self.client_connection, client_address = listen_socket.accept()

|

||||

# 处理一条请求后关闭连接,然后循环等待另一个连接建立

|

||||

self.handle_one_request()

|

||||

|

||||

def handle_one_request(self):

|

||||

self.request_data = request_data = self.client_connection.recv(1024)

|

||||

# 以 'curl -v' 的风格输出格式化请求数据

|

||||

print(''.join(

|

||||

'< {line}\n'.format(line=line)

|

||||

for line in request_data.splitlines()

|

||||

))

|

||||

|

||||

self.parse_request(request_data)

|

||||

|

||||

# 根据请求数据构建环境字典

|

||||

env = self.get_environ()

|

||||

|

||||

# 此时需要调用 Web 应用来获取结果,

|

||||

# 取回的结果将成为 HTTP 响应体

|

||||

result = self.application(env, self.start_response)

|

||||

|

||||

# 构造一个响应,回送至客户端

|

||||

self.finish_response(result)

|

||||

|

||||

def parse_request(self, text):

|

||||

request_line = text.splitlines()[0]

|

||||

request_line = request_line.rstrip('\r\n')

|

||||

# 将请求行分开成组

|

||||

(self.request_method, # GET

|

||||

self.path, # /hello

|

||||

self.request_version # HTTP/1.1

|

||||

) = request_line.split()

|

||||

|

||||

def get_environ(self):

|

||||

env = {}

|

||||

# 以下代码段没有遵循 PEP8 规则,但它这样排版,是为了通过强调

|

||||

# 所需变量及它们的值,来达到其展示目的。

|

||||

#

|

||||

# WSGI 必需变量

|

||||

env['wsgi.version'] = (1, 0)

|

||||

env['wsgi.url_scheme'] = 'http'

|

||||

env['wsgi.input'] = StringIO.StringIO(self.request_data)

|

||||

env['wsgi.errors'] = sys.stderr

|

||||

env['wsgi.multithread'] = False

|

||||

env['wsgi.multiprocess'] = False

|

||||

env['wsgi.run_once'] = False

|

||||

# CGI 必需变量

|

||||

env['REQUEST_METHOD'] = self.request_method # GET

|

||||

env['PATH_INFO'] = self.path # /hello

|

||||

env['SERVER_NAME'] = self.server_name # localhost

|

||||

env['SERVER_PORT'] = str(self.server_port) # 8888

|

||||

return env

|

||||

|

||||

def start_response(self, status, response_headers, exc_info=None):

|

||||

# 添加必要的服务器头部字段

|

||||

server_headers = [

|

||||

('Date', 'Tue, 31 Mar 2015 12:54:48 GMT'),

|

||||

('Server', 'WSGIServer 0.2'),

|

||||

]

|

||||

self.headers_set = [status, response_headers + server_headers]

|

||||

# 为了遵循 WSGI 协议,start_response 函数必须返回一个 'write'

|

||||

# 可调用对象(返回值.write 可以作为函数调用)。为了简便,我们

|

||||

# 在这里无视这个细节。

|

||||

# return self.finish_response

|

||||

|

||||

def finish_response(self, result):

|

||||

try:

|

||||

status, response_headers = self.headers_set

|

||||

response = 'HTTP/1.1 {status}\r\n'.format(status=status)

|

||||

for header in response_headers:

|

||||

response += '{0}: {1}\r\n'.format(*header)

|

||||

response += '\r\n'

|

||||

for data in result:

|

||||

response += data

|

||||

# 以 'curl -v' 的风格输出格式化请求数据

|

||||

print(''.join(

|

||||

'> {line}\n'.format(line=line)

|

||||

for line in response.splitlines()

|

||||

))

|

||||

self.client_connection.sendall(response)

|

||||

finally:

|

||||

self.client_connection.close()

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

SERVER_ADDRESS = (HOST, PORT) = '', 8888

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

def make_server(server_address, application):

|

||||

server = WSGIServer(server_address)

|

||||

server.set_app(application)

|

||||

return server

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

if __name__ == '__main__':

|

||||

if len(sys.argv) < 2:

|

||||

sys.exit('Provide a WSGI application object as module:callable')

|

||||

app_path = sys.argv[1]

|

||||

module, application = app_path.split(':')

|

||||

module = __import__(module)

|

||||

application = getattr(module, application)

|

||||

httpd = make_server(SERVER_ADDRESS, application)

|

||||

print('WSGIServer: Serving HTTP on port {port} ...\n'.format(port=PORT))

|

||||

httpd.serve_forever()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

当然,这段代码要比第一部分的服务器代码长不少,但它仍然很短(只有不到 150 行),你可以轻松理解它,而不需要深究细节。上面的服务器代码还可以做更多——它可以用来运行一些你喜欢的框架写出的 Web 应用,可以是 Pyramid,Flask,Django 或其它 Python WSGI 框架。

|

||||

|

||||

不相信吗?自己来试试看吧。把以上的代码保存为 `webserver2.py`,或直接从 Github 上下载它。如果你打算不加任何参数而直接运行它,它会抱怨一句,然后退出。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

$ python webserver2.py

|

||||

Provide a WSGI application object as module:callable

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

它想做的其实是为你的 Web 应用服务,而这才是重头戏。为了运行这个服务器,你只需要安装 Python。不过,如果你希望运行 Pyramid,Flask 或 Django 应用,你还需要先安装那些框架。那我们把这三个都装上吧。我推荐的安装方式是通过 `virtualenv` 安装。按照以下几步来做,你就可以创建并激活一个虚拟环境,并在其中安装以上三个 Web 框架。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

$ [sudo] pip install virtualenv

|

||||

$ mkdir ~/envs

|

||||

$ virtualenv ~/envs/lsbaws/

|

||||

$ cd ~/envs/lsbaws/

|

||||

$ ls

|

||||

bin include lib

|

||||

$ source bin/activate

|

||||

(lsbaws) $ pip install pyramid

|

||||

(lsbaws) $ pip install flask

|

||||

(lsbaws) $ pip install django

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

现在,你需要创建一个 Web 应用。我们先从 Pyramid 开始吧。把以下代码保存为 `pyramidapp.py`,并与刚刚的 `webserver2.py` 放置在同一目录,或直接从 Github 下载该文件:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

from pyramid.config import Configurator

|

||||

from pyramid.response import Response

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

def hello_world(request):

|

||||

return Response(

|

||||

'Hello world from Pyramid!\n',

|

||||

content_type='text/plain',

|

||||

)

|

||||

|

||||

config = Configurator()

|

||||

config.add_route('hello', '/hello')

|

||||

config.add_view(hello_world, route_name='hello')

|

||||

app = config.make_wsgi_app()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

现在,你可以用你自己的 Web 服务器来运行你的 Pyramid 应用了:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

(lsbaws) $ python webserver2.py pyramidapp:app

|

||||

WSGIServer: Serving HTTP on port 8888 ...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

你刚刚让你的服务器去加载 Python 模块 `pyramidapp` 中的可执行对象 `app`。现在你的服务器可以接收请求,并将它们转发到 Pyramid 应用中了。在浏览器中输入 http://localhost:8888/hello ,敲一下回车,然后看看结果:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

你也可以使用命令行工具 `curl` 来测试服务器:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

$ curl -v http://localhost:8888/hello

|

||||

...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

看看服务器和 `curl` 向标准输出流打印的内容吧。

|

||||

|

||||

现在来试试 `Flask`。运行步骤跟上面的一样。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

from flask import Flask

|

||||

from flask import Response

|

||||

flask_app = Flask('flaskapp')

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

@flask_app.route('/hello')

|

||||

def hello_world():

|

||||

return Response(

|

||||

'Hello world from Flask!\n',

|

||||

mimetype='text/plain'

|

||||

)

|

||||

|

||||

app = flask_app.wsgi_app

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

将以上代码保存为 `flaskapp.py`,或者直接从 Github

|

||||

下载,然后输入以下命令运行服务器:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

(lsbaws) $ python webserver2.py flaskapp:app

|

||||

WSGIServer: Serving HTTP on port 8888 ...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

现在在浏览器中输入 http://localhost:8888/hello ,敲一下回车:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

同样,尝试一下 `curl`,然后你会看到服务器返回了一条 `Flask` 应用生成的信息:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

$ curl -v http://localhost:8888/hello

|

||||

...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

这个服务器能处理 Django 应用吗?试试看吧!不过这个任务可能有点复杂,所以我建议你将整个仓库克隆下来,然后使用 Github 仓库中的 `djangoapp.py` 来完成这个实验。下面是它的源代码,你可以看到它将 Django `helloword` 工程(已使用 `Django` 的 `django-admin.py startproject` 命令创建完毕)添加到了当前的 Python 路径中,然后导入了这个工程的 WSGI 应用。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

import sys

|

||||

sys.path.insert(0, './helloworld')

|

||||

from helloworld import wsgi

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

app = wsgi.application

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

将以上代码保存为 `djangoapp.py`,然后用你的 Web 服务器运行这个 Django 应用:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

(lsbaws) $ python webserver2.py djangoapp:app

|

||||

WSGIServer: Serving HTTP on port 8888 ...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

输入以下链接,敲回车:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

你这次也可以在命令行中测试——你之前应该已经做过两次了——来确认 Django 应用处理了你的请求:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

$ curl -v http://localhost:8888/hello

|

||||

...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

你试过了吗?你确定这个服务器可以与那三个框架搭配工作吗?如果没试,请去试一下。阅读固然重要,但这个系列的内容是重建,这意味着你需要亲自动手干点活。去试一下吧。别担心,我等着你呢。不开玩笑,你真的需要试一下,亲自尝试每一步,并确保它像预期的那样工作。

|

||||

|

||||

好,你已经体验到了 WSGI 的威力:它可以使 Web 服务器及 Web 框架随意搭配。WSGI 在 Python Web 服务器及框架之间提供了一个微型接口。它非常简单,而且在服务器和框架端均可以轻易实现。下面的代码片段展示了 WSGI 接口的服务器及框架端实现:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

def run_application(application):

|

||||

"""服务器端代码。"""

|

||||

# Web 应用/框架在这里存储 HTTP 状态码以及 HTTP 响应头部,

|

||||

# 服务器会将这些信息传递给客户端

|

||||

headers_set = []

|

||||

# 用于存储 WSGI/CGI 环境变量的字典

|

||||

environ = {}

|

||||

|

||||

def start_response(status, response_headers, exc_info=None):

|

||||

headers_set[:] = [status, response_headers]

|

||||

|

||||

# 服务器唤醒可执行变量“application”,获得响应头部

|

||||

result = application(environ, start_response)

|

||||

# 服务器组装一个 HTTP 响应,将其传送至客户端

|

||||

…

|

||||

|

||||

def app(environ, start_response):

|

||||

"""一个空的 WSGI 应用"""

|

||||

start_response('200 OK', [('Content-Type', 'text/plain')])

|

||||

return ['Hello world!']

|

||||

|

||||

run_application(app)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

这是它的工作原理:

|

||||

|

||||

1. Web 框架提供一个可调用对象 `application` (WSGI 规范没有规定它的实现方式)

|

||||

2. Web 服务器每次收到来自客户端的 HTTP 请求后,会唤醒可调用对象 `applition`。它会向该对象传递一个包含 WSGI/CGI 变量的字典,以及一个可调用对象 `start_response`

|

||||

3. Web 框架或应用生成 HTTP 状态码、HTTP 响应头部,然后将它传给 `start_response` 函数,服务器会将其存储起来。同时,Web 框架或应用也会返回 HTTP 响应正文。

|

||||

4. 服务器将状态码、响应头部及响应正文组装成一个 HTTP 响应,然后将其传送至客户端(这一步并不在 WSGI 规范中,但从逻辑上讲,这一步应该包含在工作流程之中。所以为了明确这个过程,我把它写了出来)

|

||||

|

||||

这是这个接口规范的图形化表达:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

到现在为止,你已经看过了用 Pyramid, Flask 和 Django 写出的 Web 应用的代码,你也看到了一个 Web 服务器如何用代码来实现另一半(服务器端的) WSGI 规范。你甚至还看到了我们如何在不使用任何框架的情况下,使用一段代码来实现一个最简单的 WSGI Web 应用。

|

||||

|

||||

其实,当你使用上面的框架编写一个 Web 应用时,你只是在较高的层面工作,而不需要直接与 WSGI 打交道。但是我知道你一定也对 WSGI 接口的框架部分,因为你在看这篇文章呀。所以,我们不用 Pyramid, Flask 或 Django,而是自己动手来创造一个最朴素的 WSGI Web 应用(或 Web 框架),然后将它和你的服务器一起运行:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

def app(environ, start_response):

|

||||

"""一个最简单的 WSGI 应用。

|

||||

|

||||

这是你自己的 Web 框架的起点 ^_^

|

||||

"""

|

||||

status = '200 OK'

|

||||

response_headers = [('Content-Type', 'text/plain')]

|

||||

start_response(status, response_headers)

|

||||

return ['Hello world from a simple WSGI application!\n']

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

同样,将上面的代码保存至 `wsgiapp.py` 或直接从 Github 上下载该文件,然后在 Web 服务器上运行这个应用,像这样:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

(lsbaws) $ python webserver2.py wsgiapp:app

|

||||

WSGIServer: Serving HTTP on port 8888 ...

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

在浏览器中输入下面的地址,然后按下回车。这是你应该看到的结果:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

你刚刚在学习如何创建一个 Web 服务器的过程中,自己编写了一个最朴素的 WSGI Web 框架!棒极了!

|

||||

|

||||

现在,我们再回来看看服务器传给客户端的那些东西。这是在使用 HTTP 客户端调用你的 Pyramid 应用时,服务器生成的 HTTP 响应内容:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

这个响应和你在本系列第一部分中看到的 HTTP 响应有一部分共同点,但它还多出来了一些内容。比如说,它拥有四个你曾经没见过的 HTTP 头部:`Content-Type`, `Content-Length`, `Date` 以及 `Server`。这些头部内容基本上在每个 Web 服务器返回的响应中都会出现。不过,它们都不是被严格要求出现的。HTTP 请求/响应头部字段的目的,在于它可以向你传递一些关于 HTTP 请求/响应的额外信息。

|

||||

|

||||

既然你对 WSGI 接口了解的更深了一些,那我再来展示一下上面那个 HTTP 响应中的各个部分的信息来源:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

我现在还没有对上面那个 `environ` 字典做任何解释,不过基本上这个字典必须包含那些被 WSGI 规范事先定义好的 WSGI 及 CGI 变量值。服务器在解析 HTTP 请求时,会从请求中获取这些变量的值。这是 `environ` 字典应该有的样子:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Web 框架会利用以上字典中包含的信息,通过字典中的请求路径、请求动作等等来决定使用哪个视图来处理响应、在哪里读取请求正文、在哪里输出错误信息(如果有的话)。

|

||||

|

||||

现在,你已经创造了属于你自己的 WSGI Web 服务器,你也使用不同 Web 框架做了几个 Web 应用。而且,你在这个过程中也自己创造出了一个朴素的 Web 应用及框架。这个过程真是累人。现在我们来回顾一下,你的 WSGI Web 服务器在服务请求时,需要针对 WSGI 应用做些什么:

|

||||

|

||||

- 首先,服务器开始工作,然后会加载一个可调用对象 `application`,这个对象由你的 Web 框架或应用提供

|

||||

- 然后,服务器读取一个请求

|

||||

- 然后,服务器会解析这个请求

|

||||

- 然后,服务器会使用请求数据来构建一个 `environ` 字典

|

||||

- 然后,它会用 `environ` 字典及一个可调用对象 `start_response` 作为参数,来调用 `application`,并获取响应体内容。

|

||||

- 然后,服务器会使用 `application` 返回的响应体,和 `start_response` 函数设置的状态码及响应头部内容,来构建一个 HTTP 响应。

|

||||

- 最终,服务器将 HTTP 响应回送给客户端。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

这基本上是服务器要做的全部内容了。你现在有了一个可以正常工作的 WSGI 服务器,它可以为使用任何遵循 WSGI 规范的 Web 框架(如 Django, Flask, Pyramid, 还有你刚刚自己写的那个框架)构建出的 Web 应用服务。最棒的部分在于,它可以在不用更改任何服务器代码的情况下,与多个不同的 Web 框架一起工作。真不错。

|

||||

|

||||

在结束之前,你可以想想这个问题:“你该如何让你的服务器在同一时间处理多个请求呢?”

|

||||

|

||||

敬请期待,我会在第三部分向你展示一种解决这个问题的方法。干杯!

|

||||

|

||||

顺便,我在撰写一本名为《搭个 Web 服务器:从头开始》的书。这本书讲解了如何从头开始编写一个基本的 Web 服务器,里面包含本文中没有的更多细节。订阅邮件列表,你就可以获取到这本书的最新进展,以及发布日期。

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://ruslanspivak.com/lsbaws-part2/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Ruslan][a]

|

||||

译者:[StdioA](https://github.com/StdioA)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]: https://github.com/rspivak/

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user