mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-03-18 02:00:18 +08:00

Translated by qhwdw

This commit is contained in:

parent

ceed2592d3

commit

58f7450664

@ -1,76 +0,0 @@

|

||||

Translating by qhwdw [20090211 Page Cache, the Affair Between Memory and Files][1]

|

||||

============================================================

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Previously we looked at how the kernel [manages virtual memory][2] for a user process, but files and I/O were left out. This post covers the important and often misunderstood relationship between files and memory and its consequences for performance.

|

||||

|

||||

Two serious problems must be solved by the OS when it comes to files. The first one is the mind-blowing slowness of hard drives, and [disk seeks in particular][3], relative to memory. The second is the need to load file contents in physical memory once and share the contents among programs. If you use [Process Explorer][4] to poke at Windows processes, you'll see there are ~15MB worth of common DLLs loaded in every process. My Windows box right now is running 100 processes, so without sharing I'd be using up to ~1.5 GB of physical RAM just for common DLLs. No good. Likewise, nearly all Linux programs need [ld.so][5] and libc, plus other common libraries.

|

||||

|

||||

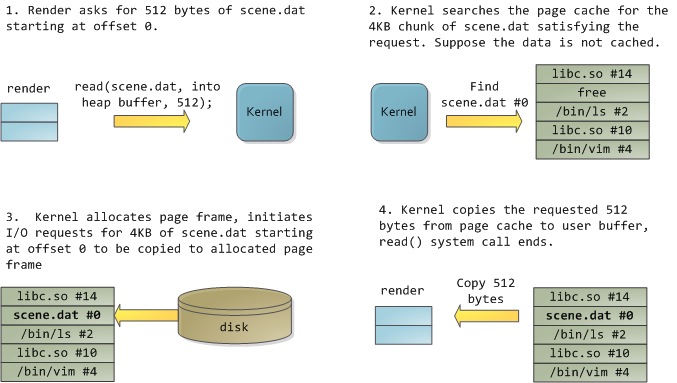

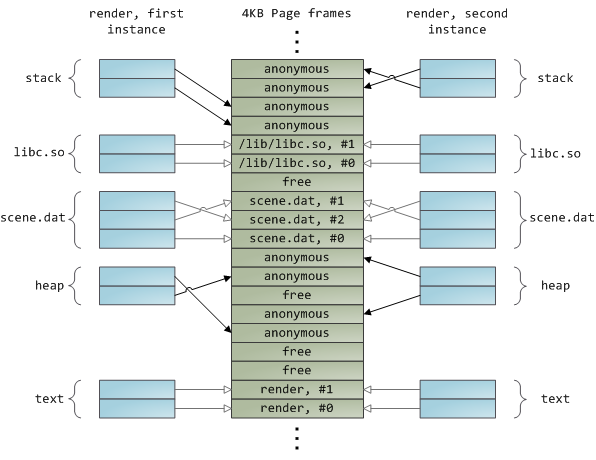

Happily, both problems can be dealt with in one shot: the page cache, where the kernel stores page-sized chunks of files. To illustrate the page cache, I'll conjure a Linux program named render, which opens file scene.dat and reads it 512 bytes at a time, storing the file contents into a heap-allocated block. The first read goes like this:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

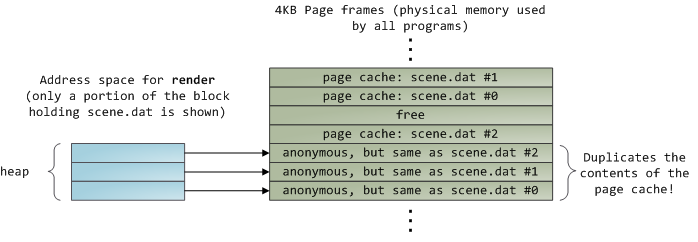

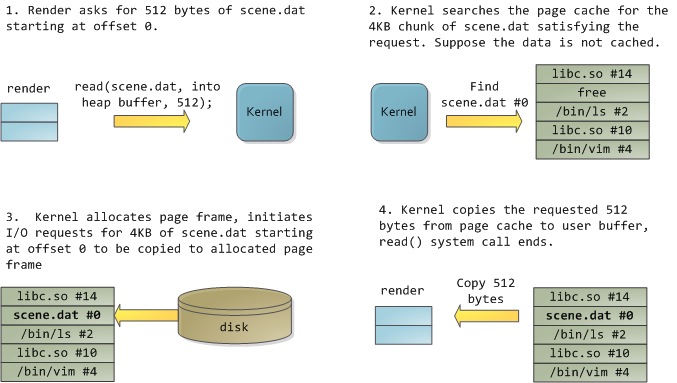

After 12KB have been read, render's heap and the relevant page frames look thus:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

This looks innocent enough, but there's a lot going on. First, even though this program uses regular read calls, three 4KB page frames are now in the page cache storing part of scene.dat. People are sometimes surprised by this, but all regular file I/O happens through the page cache. In x86 Linux, the kernel thinks of a file as a sequence of 4KB chunks. If you read a single byte from a file, the whole 4KB chunk containing the byte you asked for is read from disk and placed into the page cache. This makes sense because sustained disk throughput is pretty good and programs normally read more than just a few bytes from a file region. The page cache knows the position of each 4KB chunk within the file, depicted above as #0, #1, etc. Windows uses 256KB views analogous to pages in the Linux page cache.

|

||||

|

||||

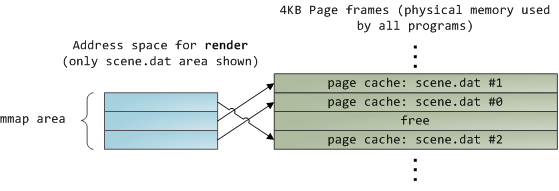

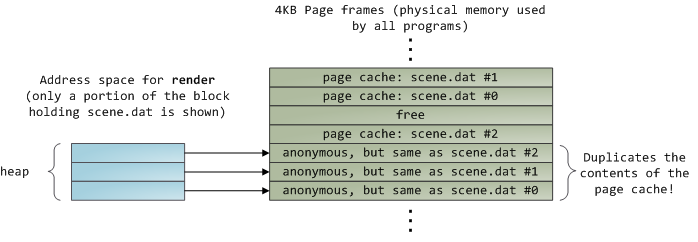

Sadly, in a regular file read the kernel must copy the contents of the page cache into a user buffer, which not only takes cpu time and hurts the [cpu caches][6], but also wastes physical memory with duplicate data. As per the diagram above, the scene.dat contents are stored twice, and each instance of the program would store the contents an additional time. We've mitigated the disk latency problem but failed miserably at everything else. Memory-mapped files are the way out of this madness:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

When you use file mapping, the kernel maps your program's virtual pages directly onto the page cache. This can deliver a significant performance boost: [Windows System Programming][7] reports run time improvements of 30% and up relative to regular file reads, while similar figures are reported for Linux and Solaris in [Advanced Programming in the Unix Environment][8]. You might also save large amounts of physical memory, depending on the nature of your application.

|

||||

|

||||

As always with performance, [measurement is everything][9], but memory mapping earns its keep in a programmer's toolbox. The API is pretty nice too, it allows you to access a file as bytes in memory and does not require your soul and code readability in exchange for its benefits. Mind your [address space][10] and experiment with [mmap][11] in Unix-like systems, [CreateFileMapping][12] in Windows, or the many wrappers available in high level languages. When you map a file its contents are not brought into memory all at once, but rather on demand via [page faults][13]. The fault handler [maps your virtual pages][14] onto the page cache after [obtaining][15] a page frame with the needed file contents. This involves disk I/O if the contents weren't cached to begin with.

|

||||

|

||||

Now for a pop quiz. Imagine that the last instance of our render program exits. Would the pages storing scene.dat in the page cache be freed immediately? People often think so, but that would be a bad idea. When you think about it, it is very common for us to create a file in one program, exit, then use the file in a second program. The page cache must handle that case. When you think more about it, why should the kernel ever get rid of page cache contents? Remember that disk is 5 orders of magnitude slower than RAM, hence a page cache hit is a huge win. So long as there's enough free physical memory, the cache should be kept full. It is therefore not dependent on a particular process, but rather it's a system-wide resource. If you run render a week from now and scene.dat is still cached, bonus! This is why the kernel cache size climbs steadily until it hits a ceiling. It's not because the OS is garbage and hogs your RAM, it's actually good behavior because in a way free physical memory is a waste. Better use as much of the stuff for caching as possible.

|

||||

|

||||

Due to the page cache architecture, when a program calls [write()][16] bytes are simply copied to the page cache and the page is marked dirty. Disk I/O normally does not happen immediately, thus your program doesn't block waiting for the disk. On the downside, if the computer crashes your writes will never make it, hence critical files like database transaction logs must be [fsync()][17]ed (though one must still worry about drive controller caches, oy!). Reads, on the other hand, normally block your program until the data is available. Kernels employ eager loading to mitigate this problem, an example of which is read ahead where the kernel preloads a few pages into the page cache in anticipation of your reads. You can help the kernel tune its eager loading behavior by providing hints on whether you plan to read a file sequentially or randomly (see [madvise()][18], [readahead()][19], [Windows cache hints][20] ). Linux [does read-ahead][21] for memory-mapped files, but I'm not sure about Windows. Finally, it's possible to bypass the page cache using [O_DIRECT][22] in Linux or [NO_BUFFERING][23] in Windows, something database software often does.

|

||||

|

||||

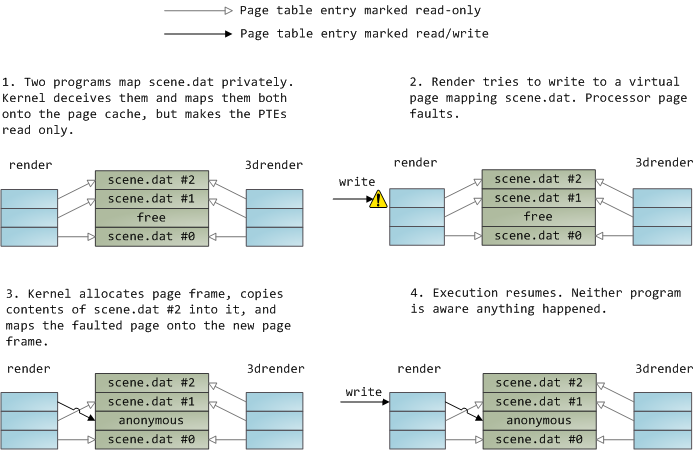

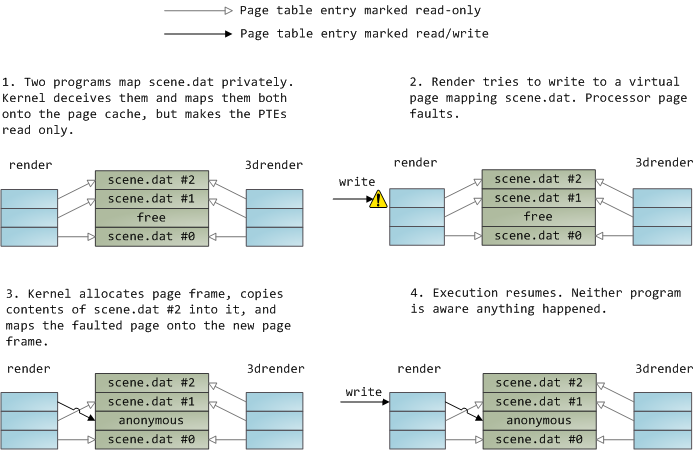

A file mapping may be private or shared. This refers only to updates made to the contents in memory: in a private mapping the updates are not committed to disk or made visible to other processes, whereas in a shared mapping they are. Kernels use the copy on write mechanism, enabled by page table entries, to implement private mappings. In the example below, both render and another program called render3d (am I creative or what?) have mapped scene.dat privately. Render then writes to its virtual memory area that maps the file:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The read-only page table entries shown above do not mean the mapping is read only, they're merely a kernel trick to share physical memory until the last possible moment. You can see how 'private' is a bit of a misnomer until you remember it only applies to updates. A consequence of this design is that a virtual page that maps a file privately sees changes done to the file by other programs as long as the page has only been read from. Once copy-on-write is done, changes by others are no longer seen. This behavior is not guaranteed by the kernel, but it's what you get in x86 and makes sense from an API perspective. By contrast, a shared mapping is simply mapped onto the page cache and that's it. Updates are visible to other processes and end up in the disk. Finally, if the mapping above were read-only, page faults would trigger a segmentation fault instead of copy on write.

|

||||

|

||||

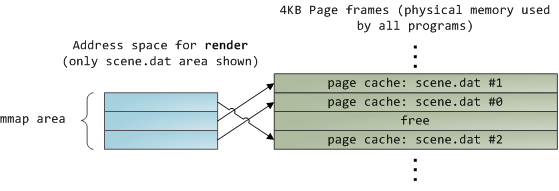

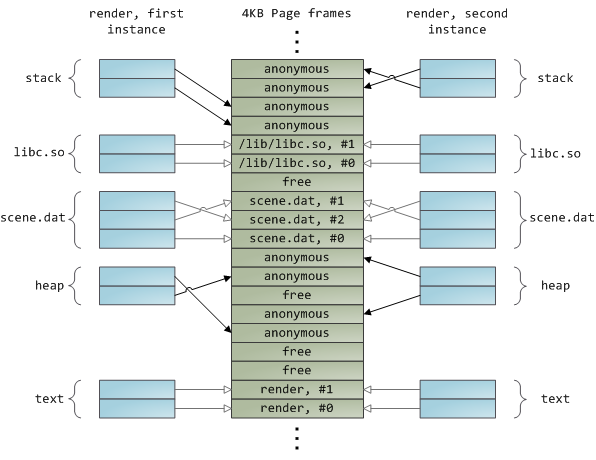

Dynamically loaded libraries are brought into your program's address space via file mapping. There's nothing magical about it, it's the same private file mapping available to you via regular APIs. Below is an example showing part of the address spaces from two running instances of the file-mapping render program, along with physical memory, to tie together many of the concepts we've seen.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

This concludes our 3-part series on memory fundamentals. I hope the series was useful and provided you with a good mental model of these OS topics.

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via:https://manybutfinite.com/post/page-cache-the-affair-between-memory-and-files/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Gustavo Duarte][a]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/about/

|

||||

[1]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/page-cache-the-affair-between-memory-and-files/

|

||||

[2]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/how-the-kernel-manages-your-memory

|

||||

[3]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/what-your-computer-does-while-you-wait

|

||||

[4]:http://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/sysinternals/bb896653.aspx

|

||||

[5]:http://ld.so

|

||||

[6]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/intel-cpu-caches

|

||||

[7]:http://www.amazon.com/Windows-Programming-Addison-Wesley-Microsoft-Technology/dp/0321256190/

|

||||

[8]:http://www.amazon.com/Programming-Environment-Addison-Wesley-Professional-Computing/dp/0321525949/

|

||||

[9]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/performance-is-a-science

|

||||

[10]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/anatomy-of-a-program-in-memory

|

||||

[11]:http://www.kernel.org/doc/man-pages/online/pages/man2/mmap.2.html

|

||||

[12]:http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/aa366537(VS.85).aspx

|

||||

[13]:http://lxr.linux.no/linux+v2.6.28/mm/memory.c#L2678

|

||||

[14]:http://lxr.linux.no/linux+v2.6.28/mm/memory.c#L2436

|

||||

[15]:http://lxr.linux.no/linux+v2.6.28/mm/filemap.c#L1424

|

||||

[16]:http://www.kernel.org/doc/man-pages/online/pages/man2/write.2.html

|

||||

[17]:http://www.kernel.org/doc/man-pages/online/pages/man2/fsync.2.html

|

||||

[18]:http://www.kernel.org/doc/man-pages/online/pages/man2/madvise.2.html

|

||||

[19]:http://www.kernel.org/doc/man-pages/online/pages/man2/readahead.2.html

|

||||

[20]:http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/aa363858(VS.85).aspx#caching_behavior

|

||||

[21]:http://lxr.linux.no/linux+v2.6.28/mm/filemap.c#L1424

|

||||

[22]:http://www.kernel.org/doc/man-pages/online/pages/man2/open.2.html

|

||||

[23]:http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/cc644950(VS.85).aspx

|

||||

@ -0,0 +1,76 @@

|

||||

[页面缓存,内存和文件之间的那些事][1]

|

||||

============================================================

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

上一篇文章中我们学习了内核怎么为一个用户进程 [管理虚拟内存][2],而忽略了文件和 I/O。这一篇文章我们将专门去讲这个重要的主题 —— 页面缓存。文件和内存之间的关系常常很不好去理解,而它们对系统性能的影响却是非常大的。

|

||||

|

||||

在面对文件时,有两个很重要的问题需要操作系统去解决。第一个是相对内存而言,慢的让人发狂的硬盘驱动器,[尤其是磁盘查找][3]。第二个是需要将文件内容一次性地加载到物理内存中,以便程序间共享文件内容。如果你在 Windows 中使用 [进程浏览器][4] 去查看它的进程,你将会看到每个进程中加载了大约 ~15MB 的公共 DLLs。我的 Windows 机器上现在大约运行着 100 个进程,因此,如果不共享的话,仅这些公共的 DLLs 就要使用高达 ~1.5 GB 的物理内存。如果是那样的话,那就太糟糕了。同样的,几乎所有的 Linux 进程都需要 [ld.so][5] 和 libc,加上其它的公共库,它们占用的内存数量也不是一个小数目。

|

||||

|

||||

幸运的是,所有的这些问题都用一个办法解决了:页面缓存 —— 保存在内存中的页面大小的文件块。为了用图去说明页面缓存,我捏造出一个名为 Render 的 Linux 程序,它打开了文件 scene.dat,并且一次读取 512 字节,并将文件内容存储到一个分配的堆块中。第一次读取的过程如下:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

读取完 12KB 的文件内容以后,Render 程序的堆和相关的页面帧如下图所示:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

它看起来很简单,其实这一过程做了很多的事情。首先,虽然这个程序使用了普通的读取调用,但是,已经有三个 4KB 的页面帧将文件 scene.dat 的一部分内容保存在了页面缓存中。虽然有时让人觉得很惊奇,但是,普通的文件 I/O 就是这样通过页面缓存来进行的。在 x86 架构的 Linux 中,内核将文件认为是一系列的 4KB 大小的块。如果你从文件中读取单个字节,包含这个字节的整个 4KB 块将被从磁盘中读入到页面缓存中。这是可以理解的,因为磁盘通常是持续吞吐的,并且程序读取的磁盘区域也不仅仅只保存几个字节。页面缓存知道文件中的每个 4KB 块的位置,在上图中用 #0、#1、等等来描述。Windows 也是类似的,使用 256KB 大小的页面缓存。

|

||||

|

||||

不幸的是,在一个普通的文件读取中,内核必须拷贝页面缓存中的内容到一个用户缓存中,它不仅花费 CPU 时间和影响 [CPU 缓存][6],在复制数据时也浪费物理内存。如前面的图示,scene.dat 的内存被保存了两次,并且,程序中的每个实例都在另外的时间中去保存了内容。我们虽然解决了从磁盘中读取文件缓慢的问题,但是在其它的方面带来了更痛苦的问题。内存映射文件是解决这种痛苦的一个方法:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

当你使用文件映射时,内核直接在页面缓存上映射你的程序的虚拟页面。这样可以显著提升性能:[Windows 系统编程][7] 的报告指出,在相关的普通文件读取上运行时性能有多达 30% 的提升,在 [Unix 环境中的高级编程][8] 的报告中,文件映射在 Linux 和 Solaris 也有类似的效果。取决于你的应用程序类型的不同,通过使用文件映射,可以节约大量的物理内存。

|

||||

|

||||

对高性能的追求是永衡不变的目标,[测量是很重要的事情][9],内存映射应该是程序员始终要使用的工具。而 API 提供了非常好用的实现方式,它允许你通过内存中的字节去访问一个文件,而不需要为了这种好处而牺牲代码可读性。在一个类 Unix 的系统中,可以使用 [mmap][11] 查看你的 [地址空间][10],在 Windows 中,可以使用 [CreateFileMapping][12],或者在高级编程语言中还有更多的可用封装。当你映射一个文件内容时,它并不是一次性将全部内容都映射到内存中,而是通过 [页面故障][13] 来按需映射的。在 [获取][15] 需要的文件内容的页面帧后,页面故障句柄在页面缓存上 [映射你的虚拟页面][14] 。如果一开始文件内容没有缓存,这还将涉及到磁盘 I/O。

|

||||

|

||||

假设我们的 Reader 程序是持续存在的实例,现在出现一个突发的状况。在页面缓存中保存着 scene.dat 内容的页面要立刻释放掉吗?这是一个人们经常要考虑的问题,但是,那样做并不是个好主意。你应该想到,我们经常在一个程序中创建一个文件,退出程序,然后,在第二个程序去使用这个文件。页面缓存正好可以处理这种情况。如果考虑更多的情况,内核为什么要清除页面缓存的内容?请记住,磁盘读取的速度要慢于内存 5 个数量级,因此,命中一个页面缓存是一件有非常大收益的事情。因此,只要有足够大的物理内存,缓存就应该始终完整保存。并且,这一原则适用于所有的进程。如果你现在运行 Render,一周后 scene.dat 的内容还在缓存中,那么应该恭喜你!这就是什么内核缓存越来越大,直至达到最大限制的原因。它并不是因为操作系统设计的太“垃圾”而浪费你的内存,其实这是一个非常好的行为,因为,释放物理内存才是一种“浪费”。(译者注:释放物理内存会导致页面缓存被清除,下次运行程序需要的相关数据,需要再次从磁盘上进行读取,会“浪费” CPU 和 I/O 资源)最好的做法是尽可能多的使用缓存。

|

||||

|

||||

由于页面缓存架构的原因,当程序调用 [write()][16] 时,字节只是被简单地拷贝到页面缓存中,并将这个页面标记为“赃”页面。磁盘 I/O 通常并不会立即发生,因此,你的程序并不会被阻塞在等待磁盘写入上。如果这时候发生了电脑死机,你的写入将不会被标记,因此,对于至关重要的文件,像数据库事务日志,必须要求 [fsync()][17]ed(仍然还需要去担心磁盘控制器的缓存失败问题),另一方面,读取将被你的程序阻塞,走到数据可用为止。内核采取预加载的方式来缓解这个矛盾,它一般提前预读取几个页面并将它加载到页面缓存中,以备你后来的读取。在你计划进行一个顺序或者随机读取时(请查看 [madvise()][18]、[readahead()][19]、[Windows cache hints][20] ),你可以通过提示(hint)帮助内核去调整这个预加载行为。Linux 会对内存映射的文件进行 [预读取][21],但是,在 Windows 上并不能确保被内存映射的文件也会预读。当然,在 Linux 中它可能会使用 [O_DIRECT][22] 跳过预读取,或者,在 Windows 中使用 [NO_BUFFERING][23] 去跳过预读,一些数据库软件就经常这么做。

|

||||

|

||||

一个内存映射的文件可以是私有的,也可以是共享的。当然,这只是针对内存中内容的更新而言:在一个私有的内存映射文件上,更新并不会提交到磁盘或者被其它进程可见,然而,共享的内存映射文件,则正好相反,它的任何更新都会提交到磁盘上,并且对其它的进程可见。内核在写机制上使用拷贝,这是通过页面表条目来实现这种私有的映射。在下面的例子中,Render 和另一个被称为 render3d 都私有映射到 scene.dat 上。然后 Render 去写入映射的文件的虚拟内存区域:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

上面展示的只读页面表条目并不意味着映射是只读的,它只是内核的一个用于去共享物理内存的技巧,直到尽可能的最后一刻之前。你可以认为“私有”一词用的有点不太恰当,你只需要记住,这个“私有”仅用于更新的情况。这种设计的重要性在于,要想看到被映射的文件的变化,其它程序只能读取它的虚拟页面。一旦“写时复制”发生,从其它地方是看不到这种变化的。但是,内核并不能保证这种行为,因为它是在 x86 中实现的,从 API 的角度来看,这是有意义的。相比之下,一个共享的映射只是将它简单地映射到页面缓存上。更新会被所有的进程看到并被写入到磁盘上。最终,如果上面的映射是只读的,页面故障将触发一个内存段失败而不是写到一个副本。

|

||||

|

||||

动态加载库是通过文件映射融入到你的程序的地址空间中的。这没有什么可奇怪的,它通过普通的 APIs 为你提供与私有文件映射相同的效果。下面的示例展示了 Reader 程序映射的文件的两个实例运行的地址空间的一部分,以及物理内存,尝试将我们看到的许多概念综合到一起。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

这是内存架构系列的第三部分的结论。我希望这个系列文章对你有帮助,对理解操作系统的这些主题提供一个很好的思维模型。

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via:https://manybutfinite.com/post/page-cache-the-affair-between-memory-and-files/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Gustavo Duarte][a]

|

||||

译者:[qhwdw](https://github.com/qhwdw)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:http://duartes.org/gustavo/blog/about/

|

||||

[1]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/page-cache-the-affair-between-memory-and-files/

|

||||

[2]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/how-the-kernel-manages-your-memory

|

||||

[3]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/what-your-computer-does-while-you-wait

|

||||

[4]:http://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/sysinternals/bb896653.aspx

|

||||

[5]:http://ld.so

|

||||

[6]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/intel-cpu-caches

|

||||

[7]:http://www.amazon.com/Windows-Programming-Addison-Wesley-Microsoft-Technology/dp/0321256190/

|

||||

[8]:http://www.amazon.com/Programming-Environment-Addison-Wesley-Professional-Computing/dp/0321525949/

|

||||

[9]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/performance-is-a-science

|

||||

[10]:https://manybutfinite.com/post/anatomy-of-a-program-in-memory

|

||||

[11]:http://www.kernel.org/doc/man-pages/online/pages/man2/mmap.2.html

|

||||

[12]:http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/aa366537(VS.85).aspx

|

||||

[13]:http://lxr.linux.no/linux+v2.6.28/mm/memory.c#L2678

|

||||

[14]:http://lxr.linux.no/linux+v2.6.28/mm/memory.c#L2436

|

||||

[15]:http://lxr.linux.no/linux+v2.6.28/mm/filemap.c#L1424

|

||||

[16]:http://www.kernel.org/doc/man-pages/online/pages/man2/write.2.html

|

||||

[17]:http://www.kernel.org/doc/man-pages/online/pages/man2/fsync.2.html

|

||||

[18]:http://www.kernel.org/doc/man-pages/online/pages/man2/madvise.2.html

|

||||

[19]:http://www.kernel.org/doc/man-pages/online/pages/man2/readahead.2.html

|

||||

[20]:http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/aa363858(VS.85).aspx#caching_behavior

|

||||

[21]:http://lxr.linux.no/linux+v2.6.28/mm/filemap.c#L1424

|

||||

[22]:http://www.kernel.org/doc/man-pages/online/pages/man2/open.2.html

|

||||

[23]:http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/cc644950(VS.85).aspx

|

||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user