mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-02-03 23:40:14 +08:00

20140703-1 选题 The history of Android 系列文章

This commit is contained in:

parent

760e06b07e

commit

5422385311

@ -0,0 +1,202 @@

|

||||

The history of Android

|

||||

================================================================================

|

||||

> Follow the endless iterations from Android 0.5 to Android 4.4.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

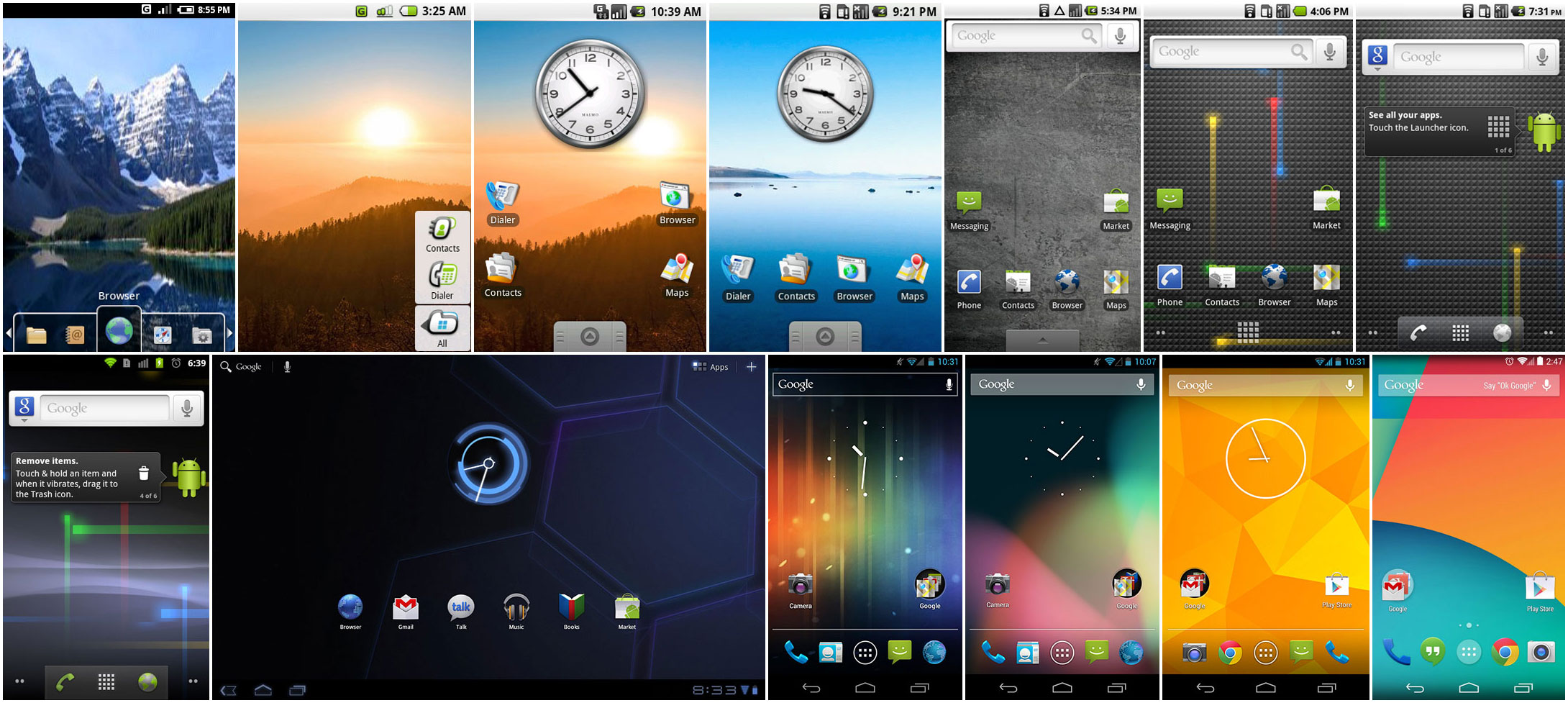

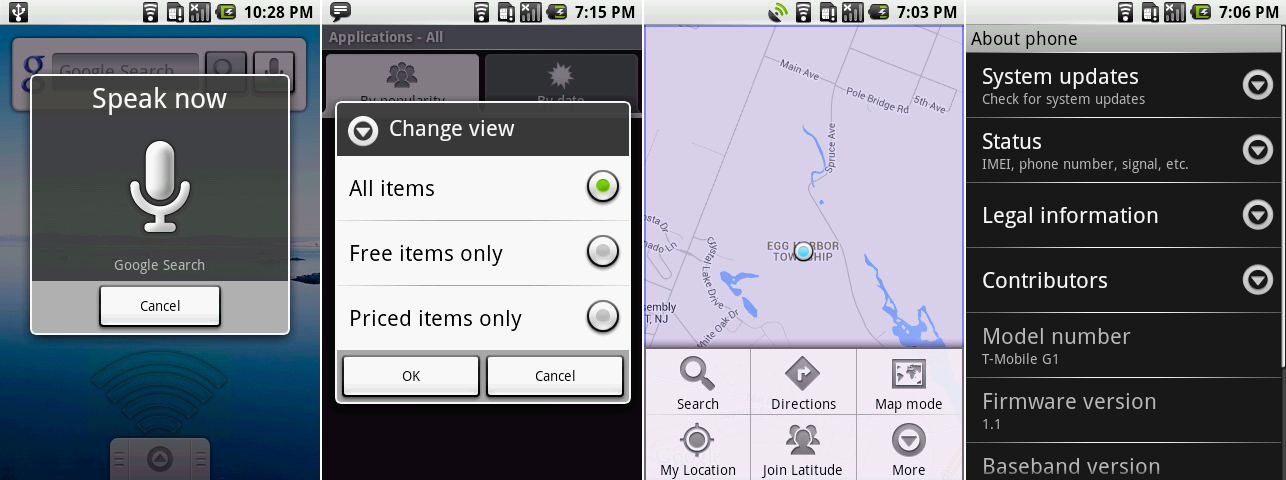

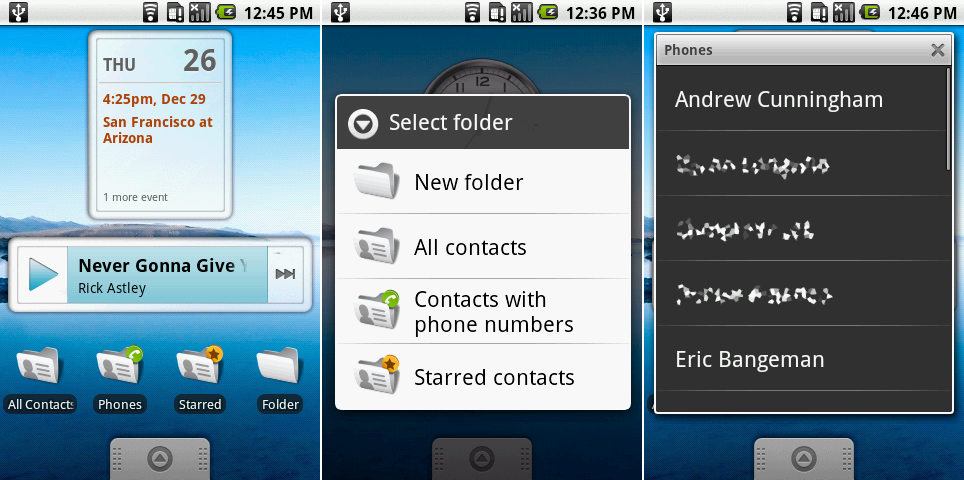

Android's home screen over the years.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

Android has been with us in one form or another for more than six years. During that time, we've seen an absolutely breathtaking rate of change unlike any other development cycle that has ever existed. When it came time for Google to dive in to the smartphone wars, the company took its rapid-iteration, Web-style update cycle and applied it to an operating system, and the result has been an onslaught of continual improvement. Lately, Android has even been running on a previously unheard of six-month development cycle, and that's slower than it used to be. For the first year of Android’s commercial existence, Google was putting out a new version every two-and-a-half months.

|

||||

|

||||

注:youtube视频地址开始

|

||||

<iframe width="640" height="480" frameborder="0" src="http://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/1FJHYqE0RDg?start=0&wmode=transparent" type="text/html" style="display:block"></iframe>

|

||||

|

||||

Google's original introduction of Android, from way back in November 2007.

|

||||

注:youtube视频地址结束

|

||||

|

||||

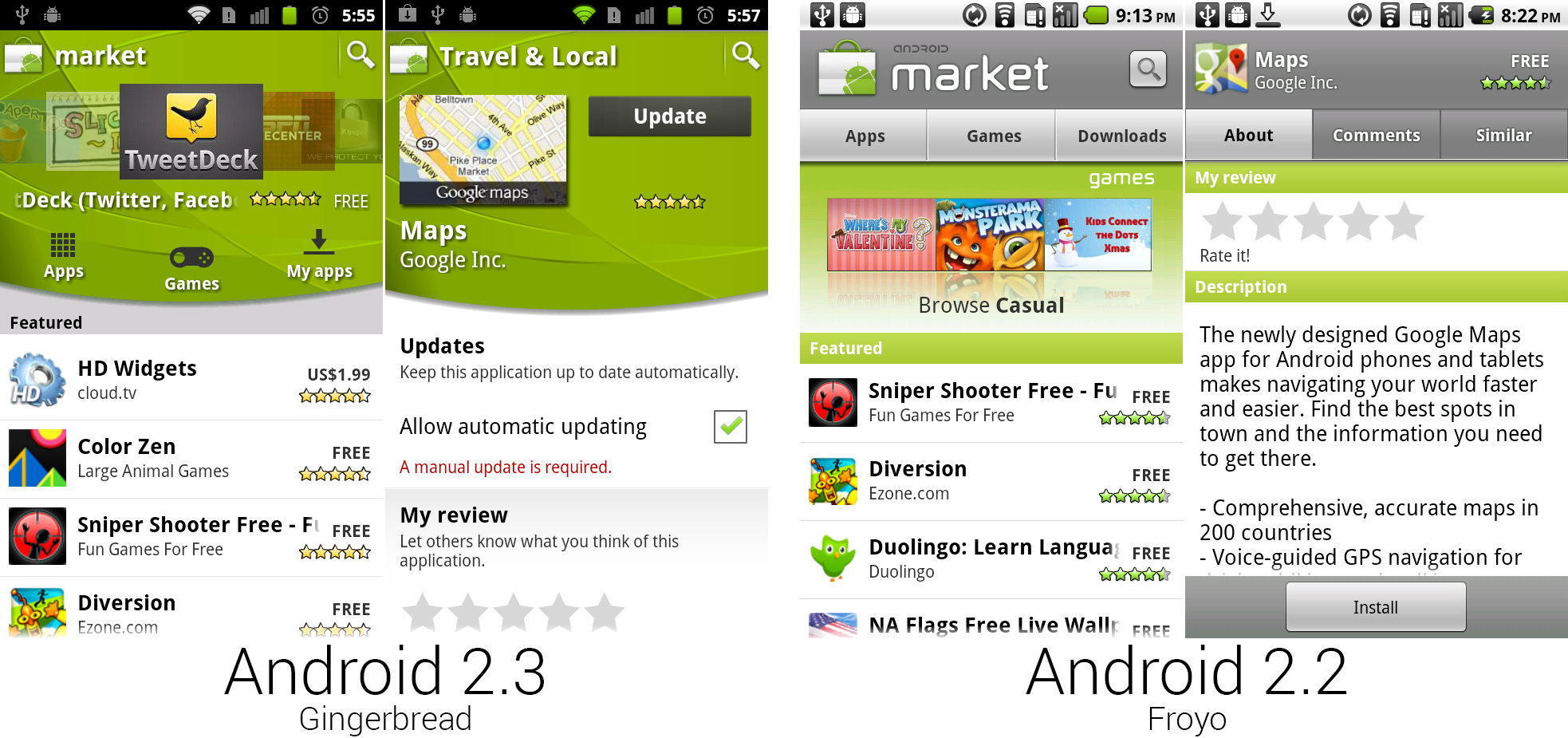

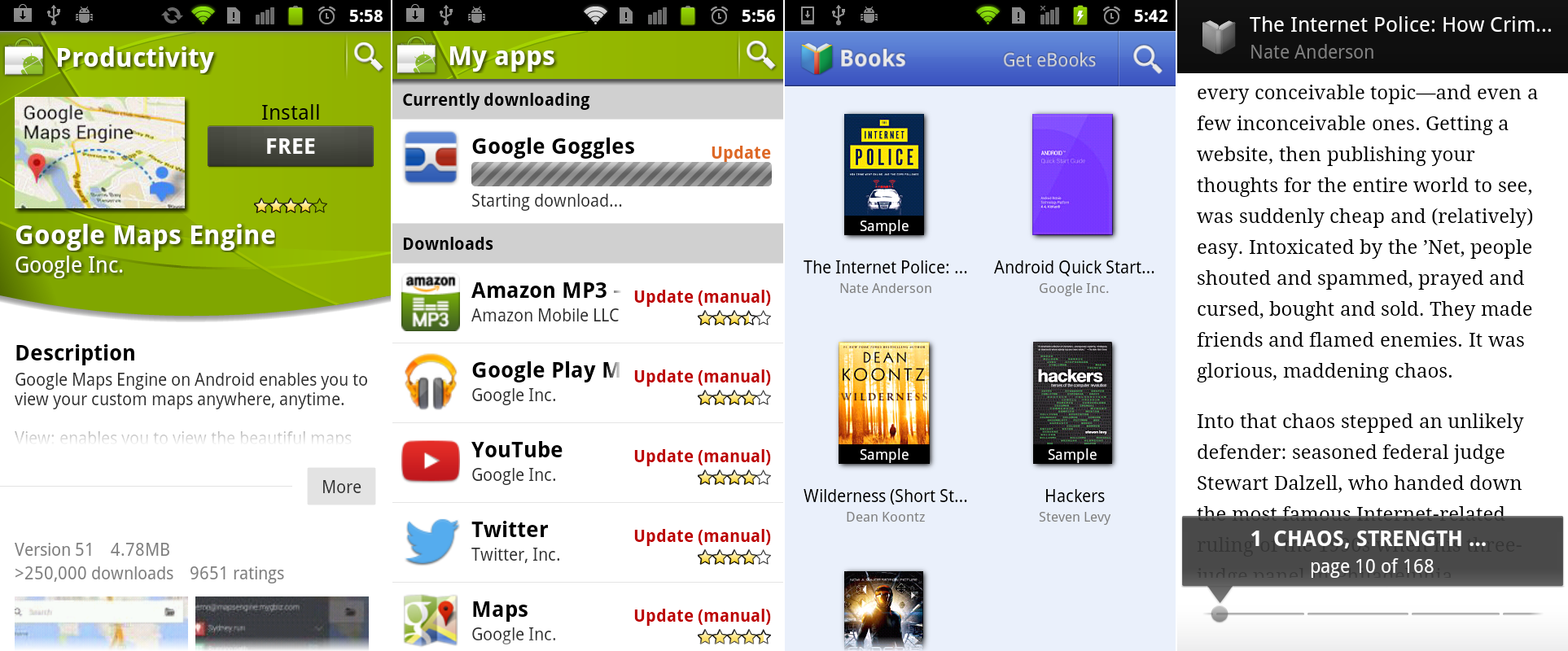

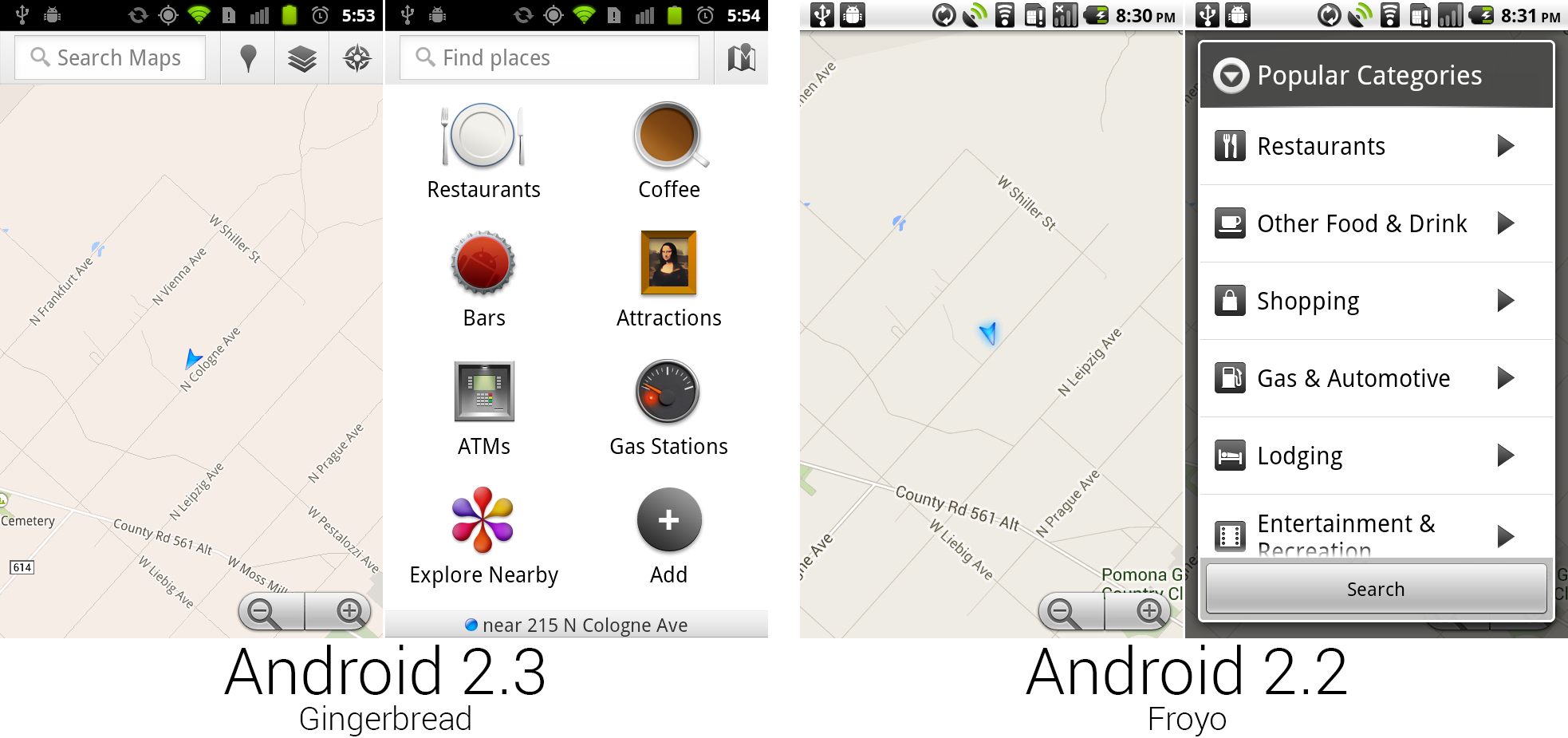

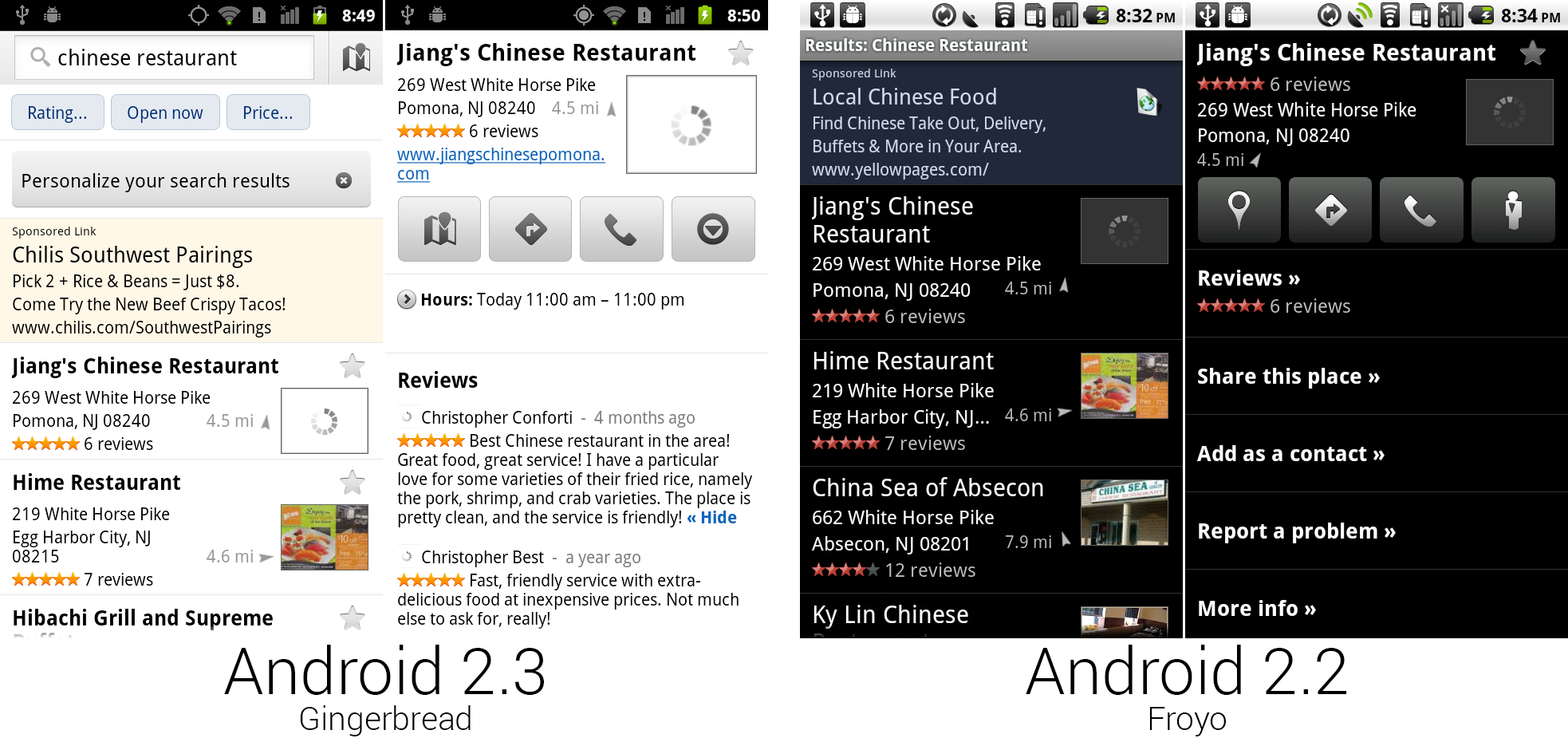

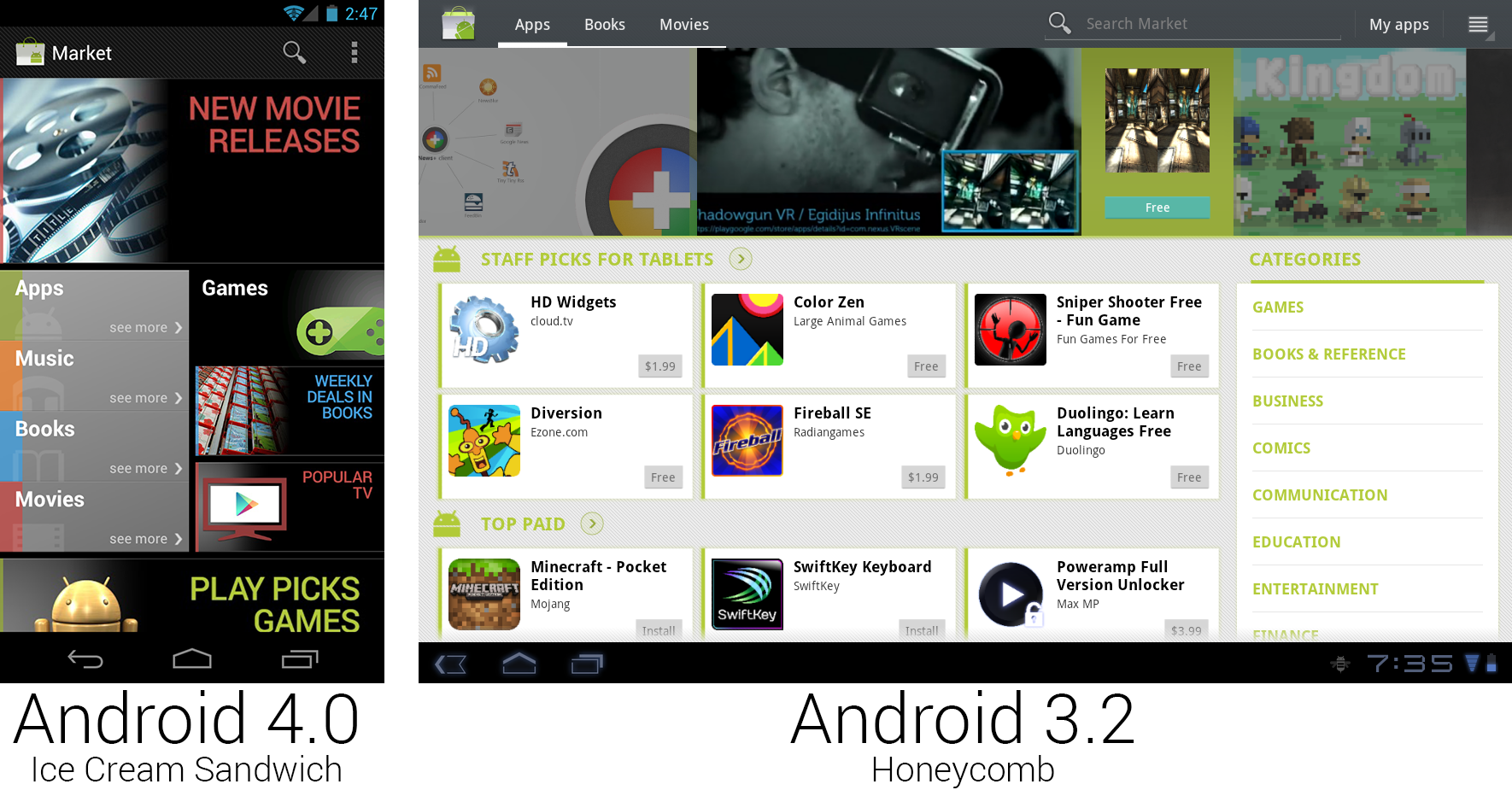

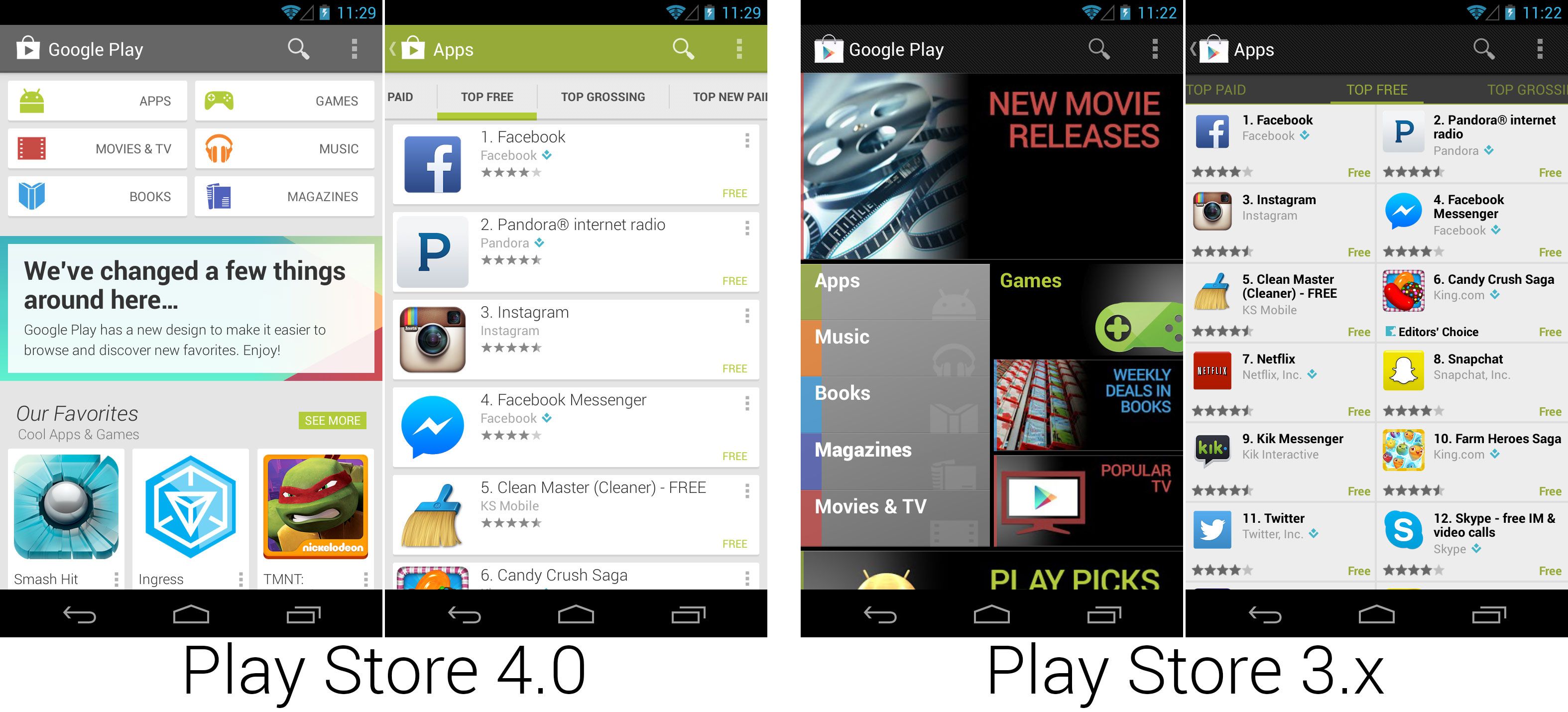

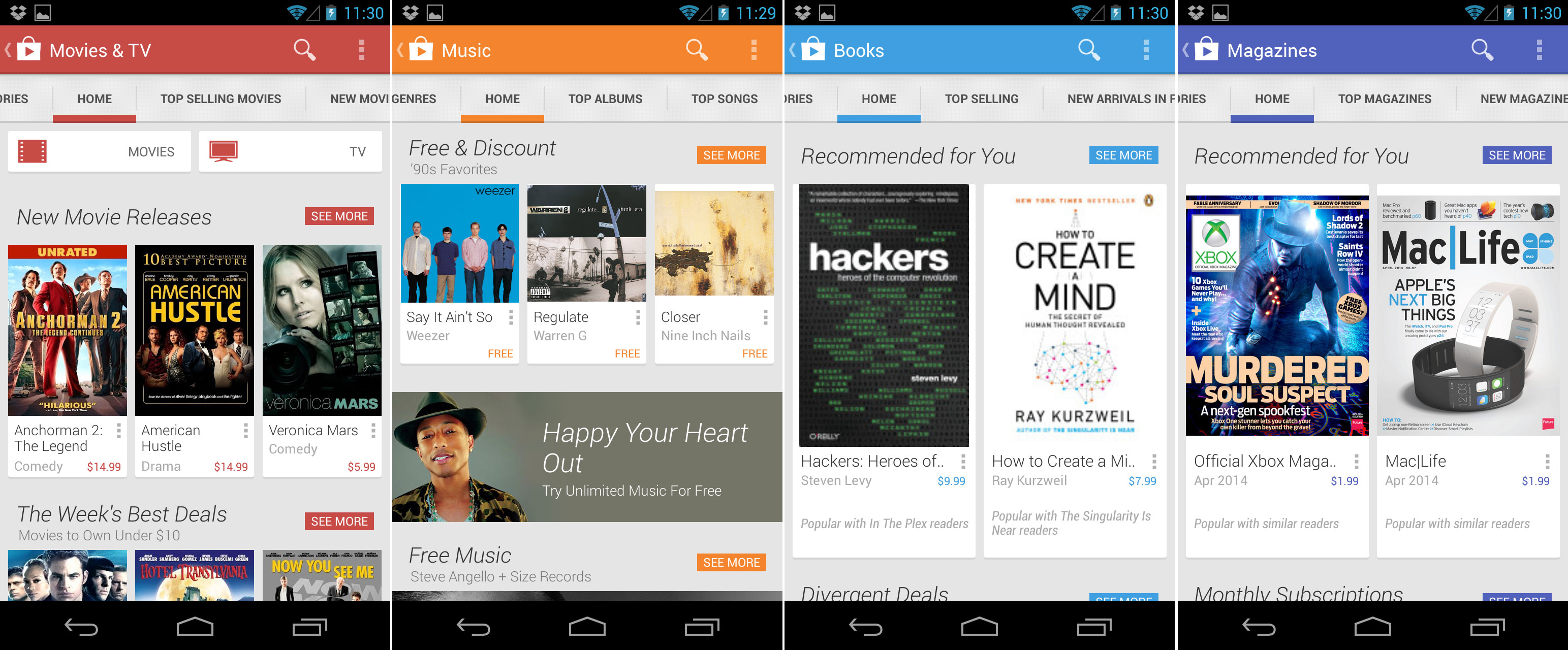

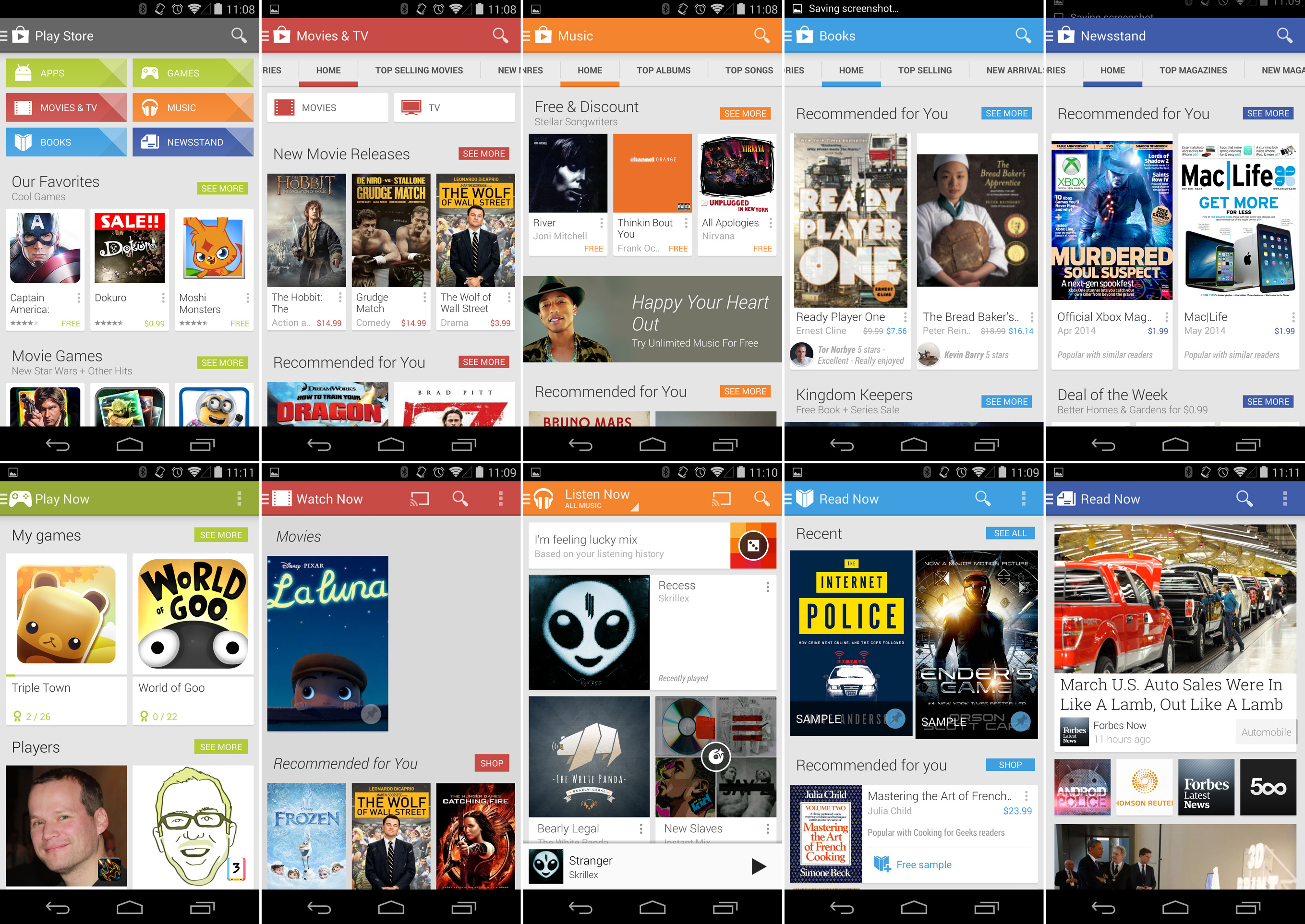

The rest of the industry, by comparison, moves at a snail's pace. Microsoft updates its desktop OS every three to five years, and Apple is on a yearly update cycle for OS X and iOS. Not every update is created equal, either. iOS has one major design revision in seven years, and the newest version of Windows Phone 8 looks very similar to Windows Phone 7. On Android, however, users are lucky if anything looks the same this year as it did last year. The Play Store, for instance, has had five major redesigns in five years. For Android, that's normal.

|

||||

|

||||

Looking back, Android's existence has been a blur. It's now a historically big operating system. Almost a billion total devices have been sold, and 1.5 million devices are activated per day—but how did Google get here? With this level of scale and success, you would think there would be tons of coverage of Android’s rise from zero to hero. However, there just isn’t. Android wasn’t very popular in the early days, and until Android 4.0, screenshots could only be taken with the developer kit. These two factors mean you aren’t going to find a lot of images or information out there about the early versions of Android.

|

||||

|

||||

The problem now with the lack of early coverage is that *early versions of Android are dying*. While something like Windows 1.0 will be around forever—just grab an old computer and install it—Android could be considered the first cloud-based operating system. Many features are heavily reliant on Google’s servers to function. With fewer and fewer people using old versions of Android, those servers are being shut down. And when a cloud-reliant app has its server support shut off, it will never work again—the app crashes and displays a blank screen, or it just refuses to start.

|

||||

|

||||

Thanks to this “[cloud rot][1]," an Android retrospective won’t be possible in a few years. Early versions of Android will be empty, broken husks that won't function without cloud support. While it’s easy to think of this as a ways off, it's happening right now. While writing this piece, we ran into tons of apps that no longer function because the server support has been turned off. Early clients for Google Maps and the Android Market, for instance, are no longer able to communicate with Google. They either throw an error message and crash or display blank screens. Some apps even worked one week and died the next, because Google was actively shutting down servers during our writing!

|

||||

|

||||

To prevent any more of Android's past from being lost to the annals of history, we did what needed to be done. This is 20+ versions of Android, seven devices, and lots and lots of screenshots cobbled together in one space. This is The History of Android, from the very first public builds to the newest version of KitKat.

|

||||

|

||||

注:下面一块为文章链接列表,发布后可以改为发布后的地址

|

||||

----------

|

||||

|

||||

### Table of Contents ###

|

||||

|

||||

- [Android 0.5 Milestone 3—the first public build][10]

|

||||

- [Android 0.5 Milestone 5—the land of scrapped interfaces][11]

|

||||

- [Android 0.9 Beta—hey, this looks familiar!][12]

|

||||

- [Android 1.0—introducing Google Apps and actual hardware][13]

|

||||

- [Android 1.1—the first truly incremental update][14]

|

||||

- [Android 1.5 Cupcake—a virtual keyboard opens up device design][15]

|

||||

- ----[Google Maps is the first built-in app to hit the Android Market][16]

|

||||

- [Android 1.6 Donut—CDMA support brings Android to any carrier][17]

|

||||

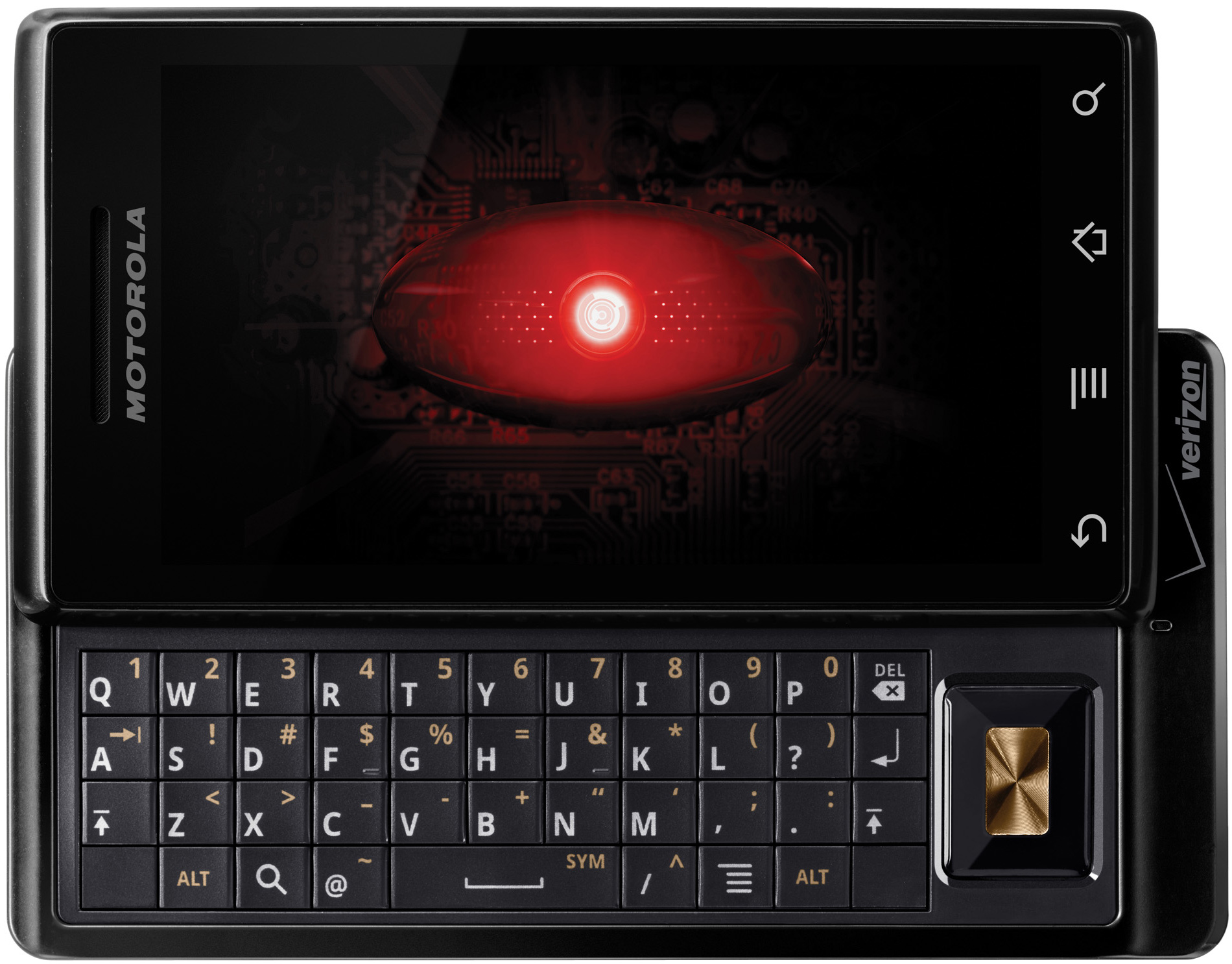

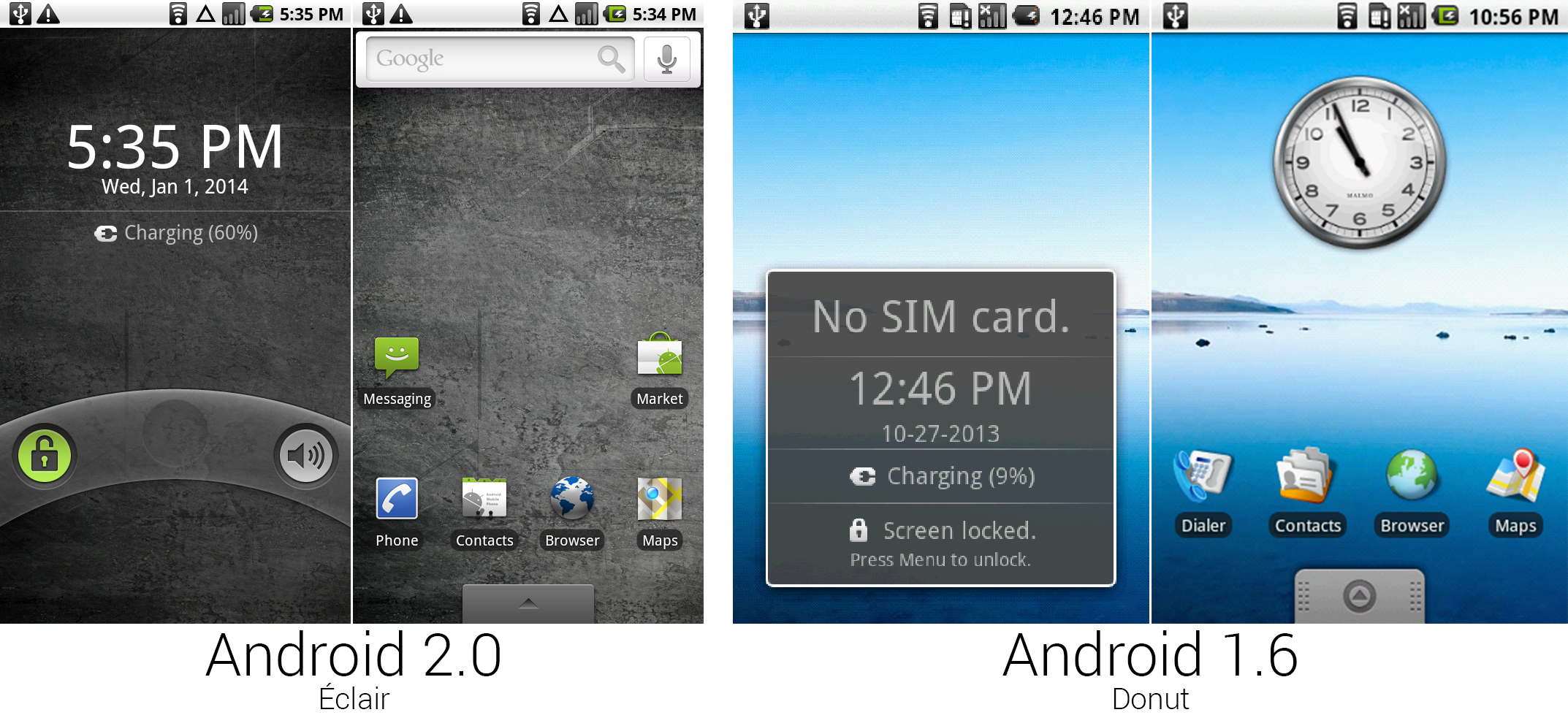

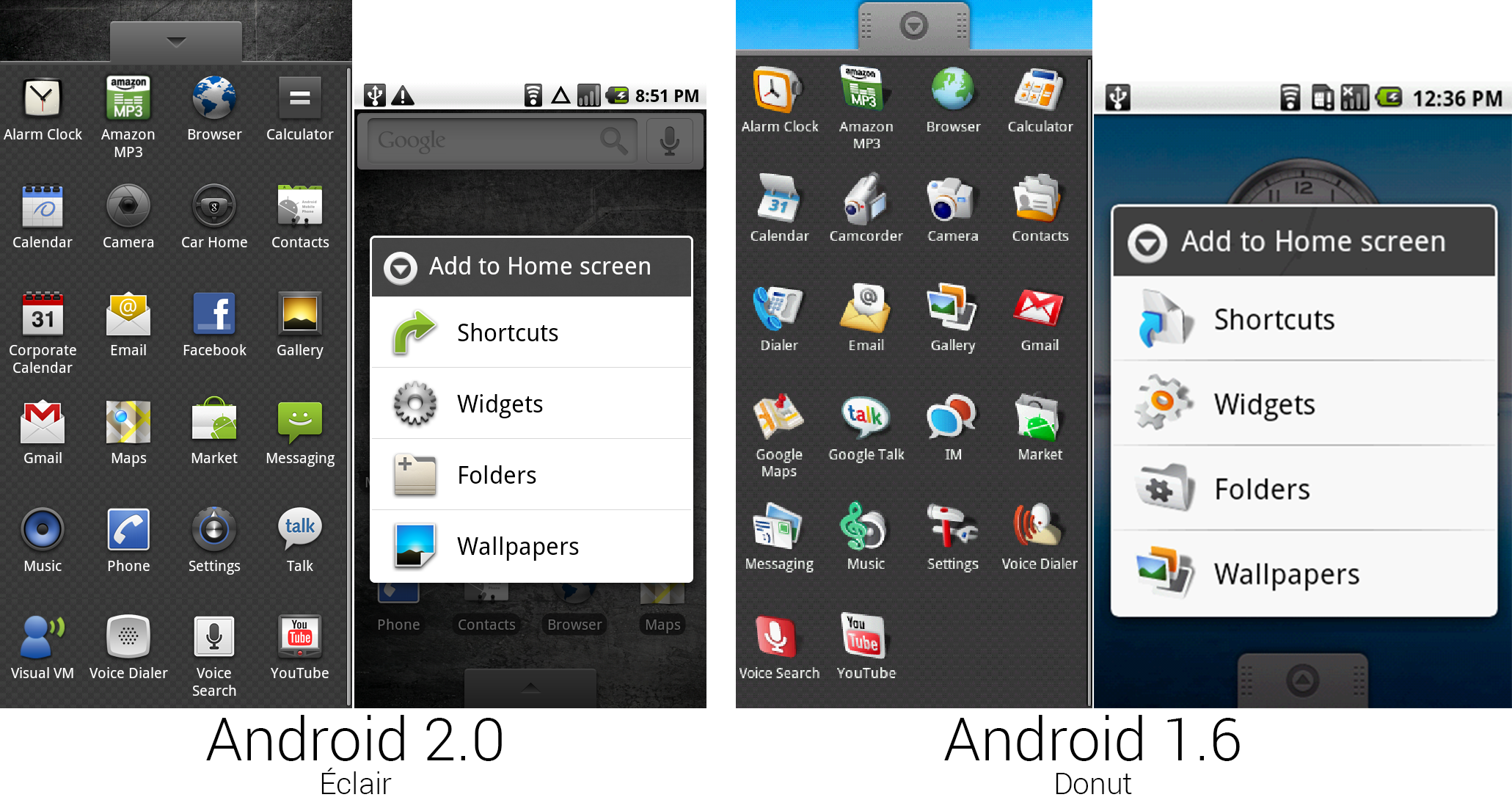

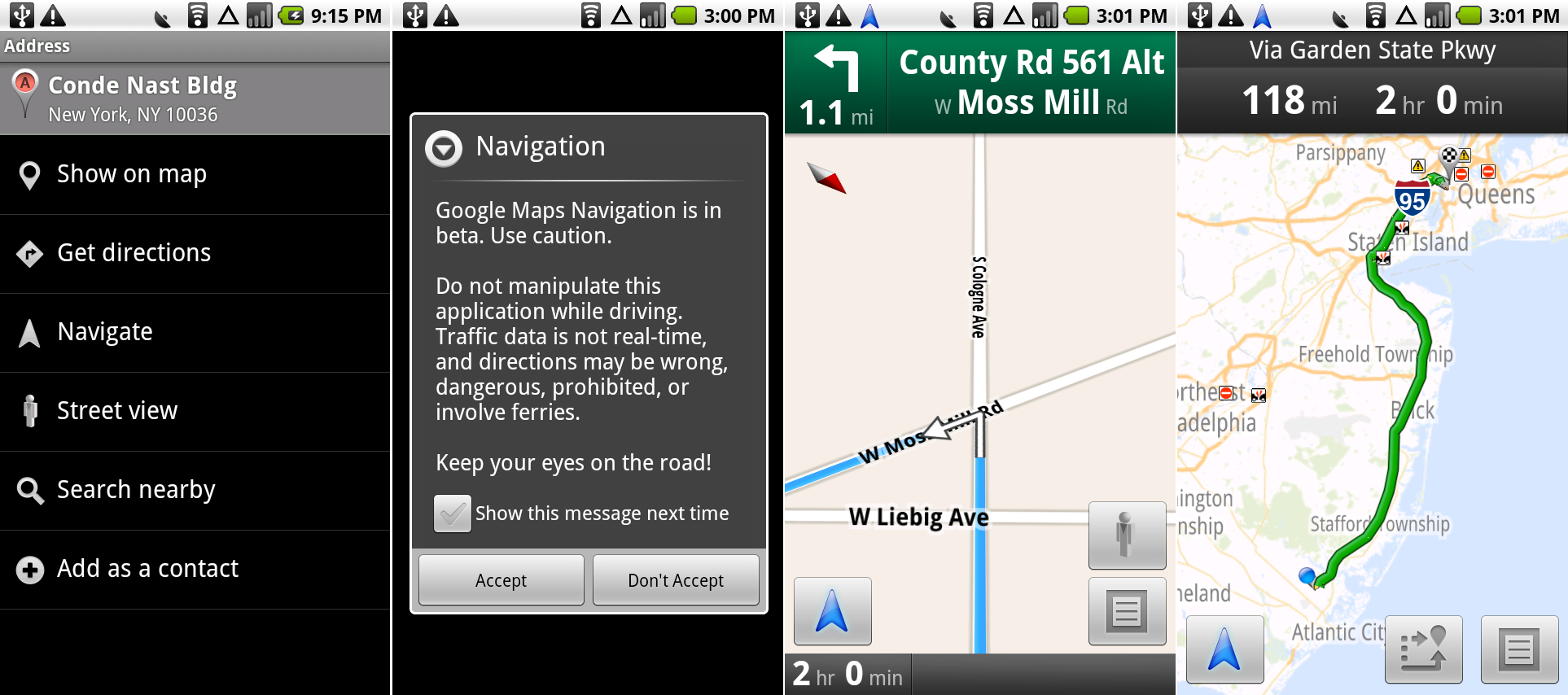

- [Android 2.0 Éclair—blowing up the GPS industry][18]

|

||||

- [The Nexus One—enter the Google Phone][19]

|

||||

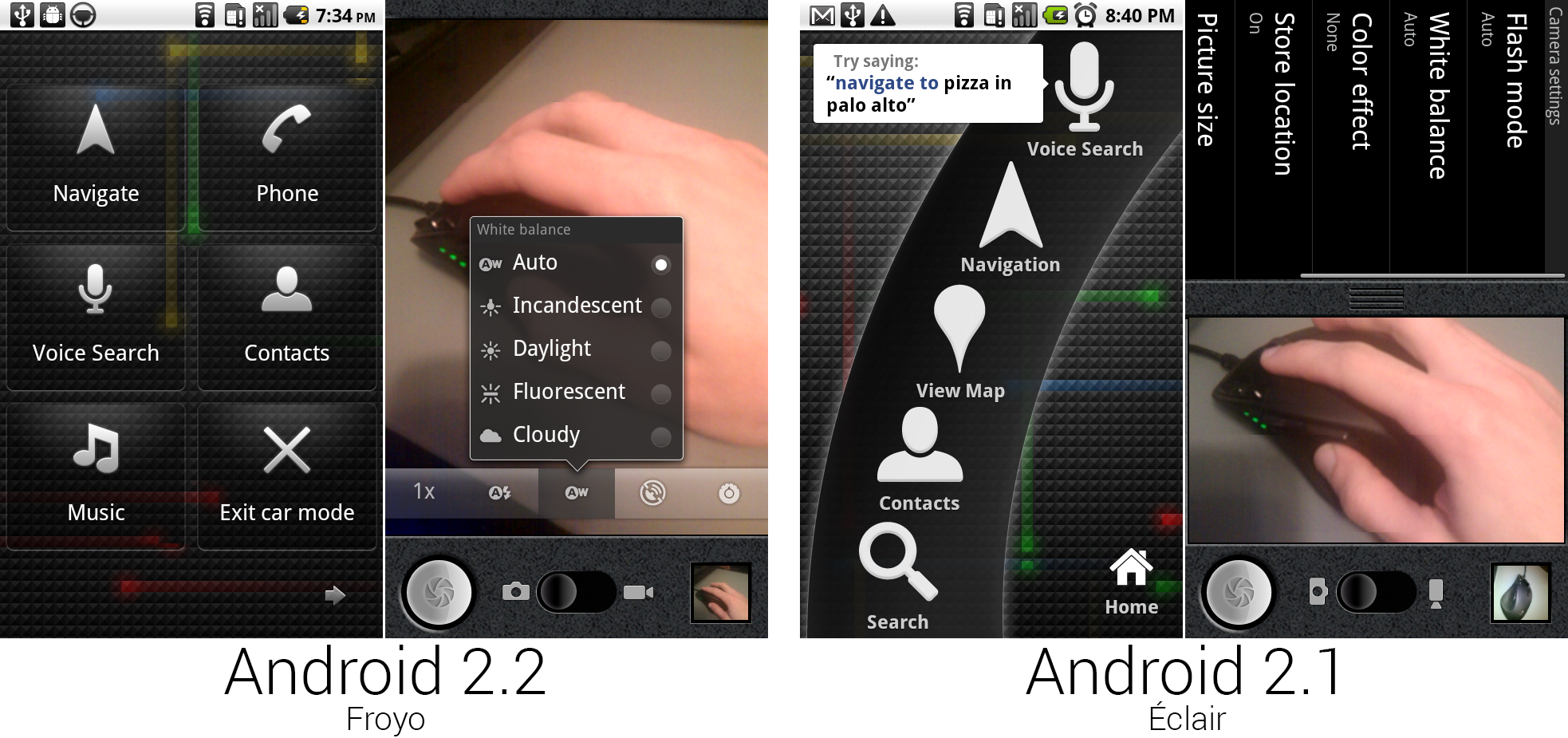

- [Android 2.1—the discovery (and abuse) of animations][20]

|

||||

- ----[Android 2.1, update 1—the beginning of an endless war][21]

|

||||

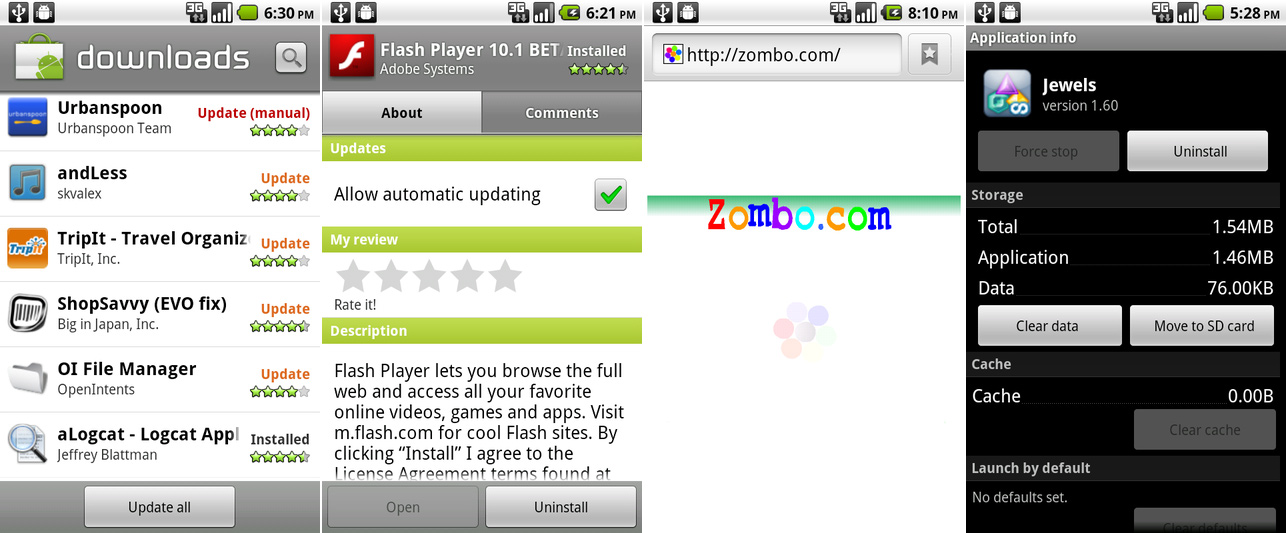

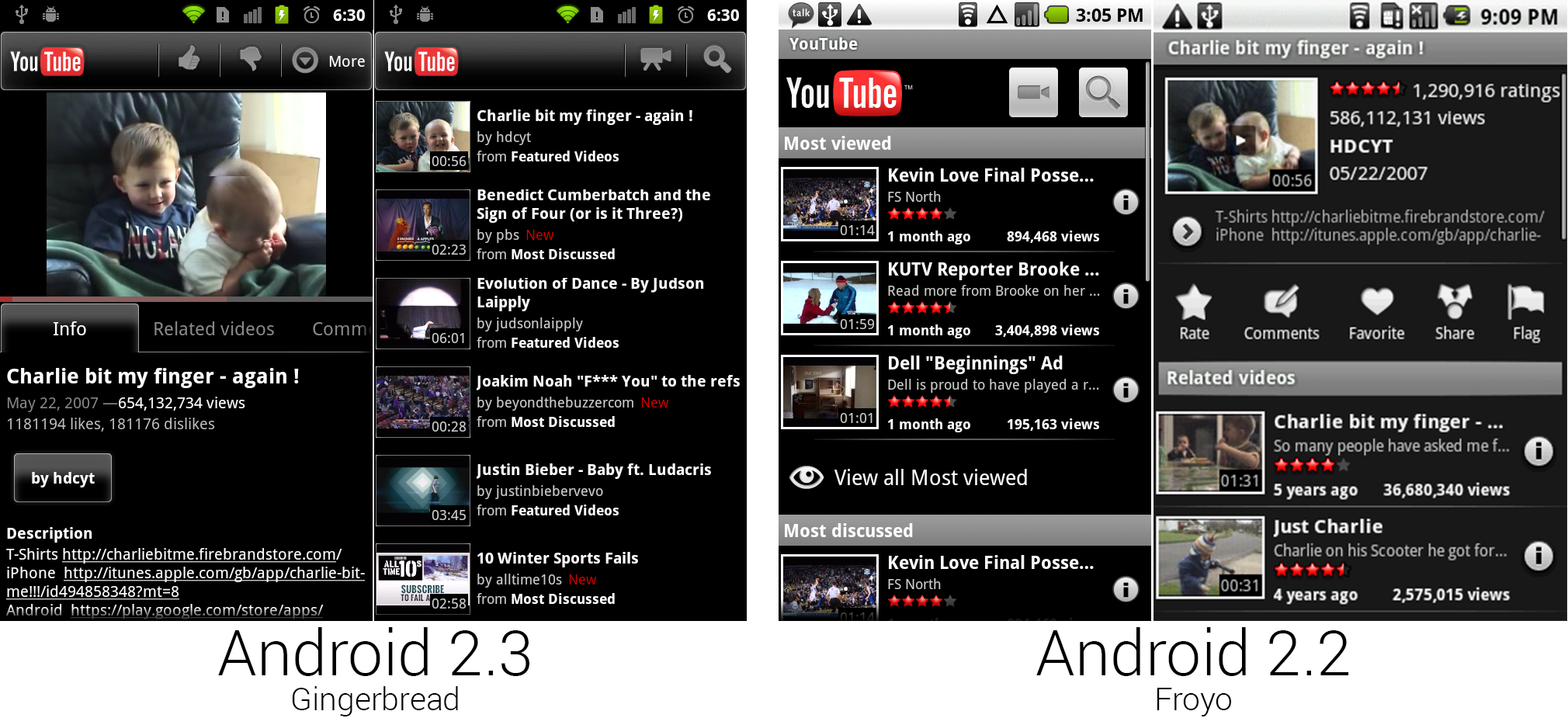

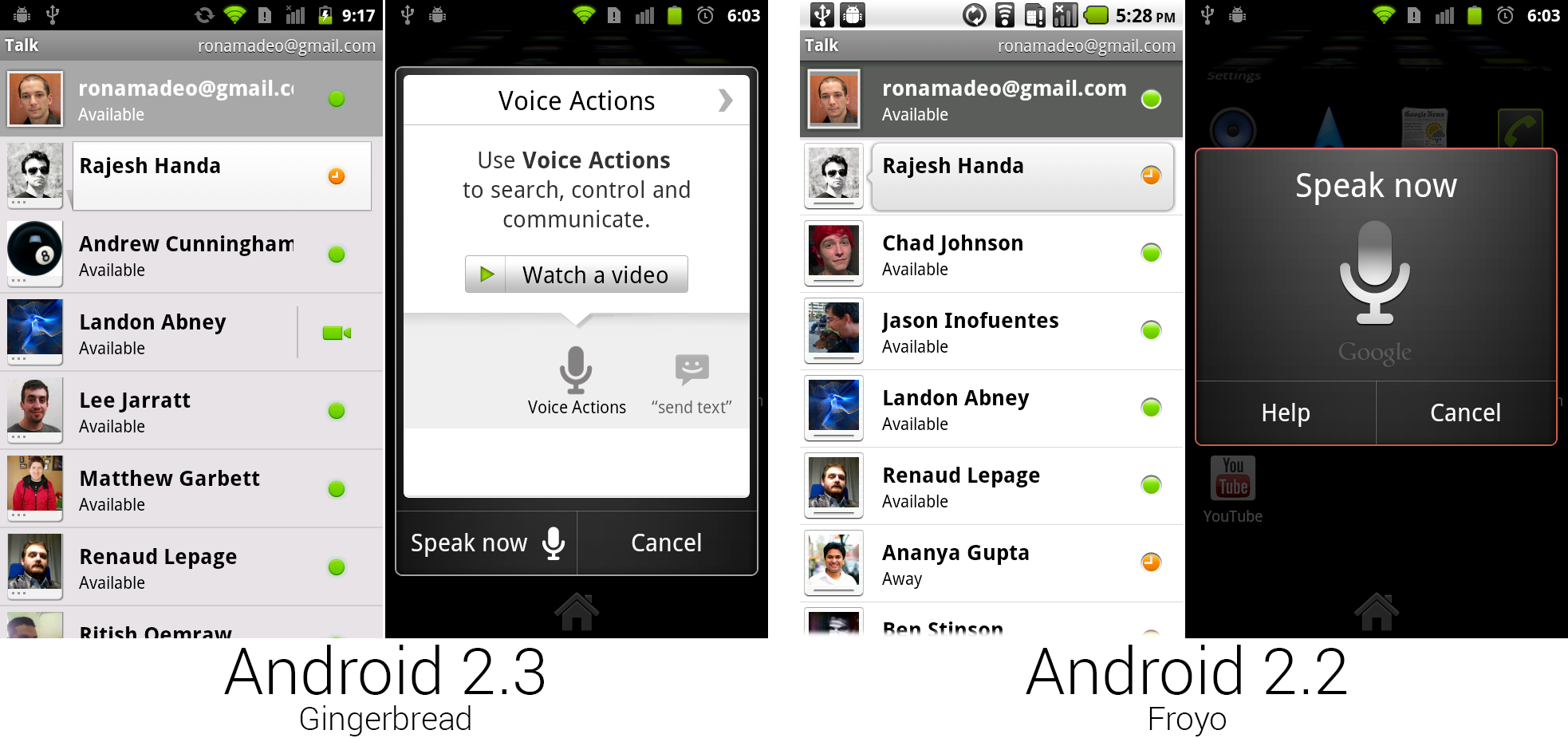

- [Android 2.2 Froyo—faster and Flash-ier][22]

|

||||

- ----[Voice Actions—a supercomputer in your pocket][23]

|

||||

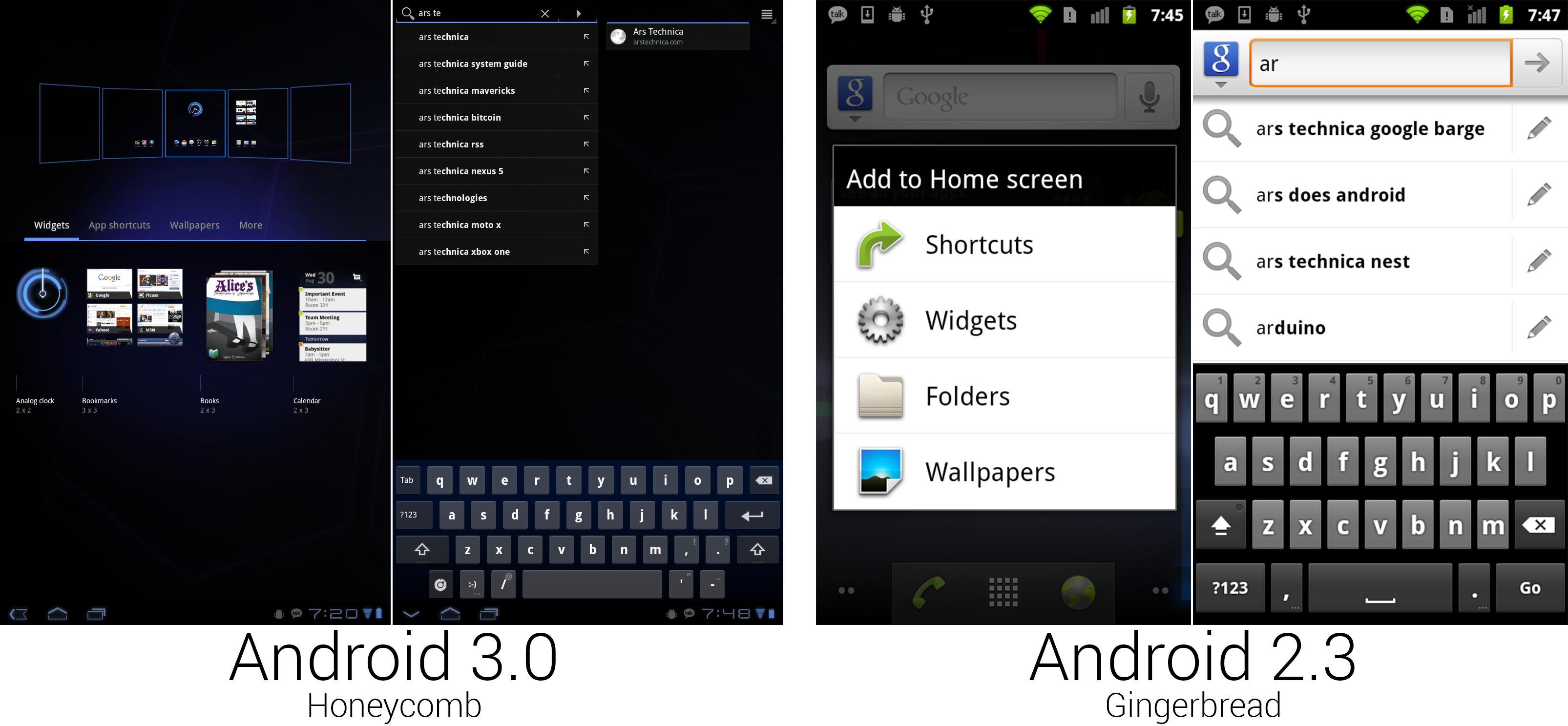

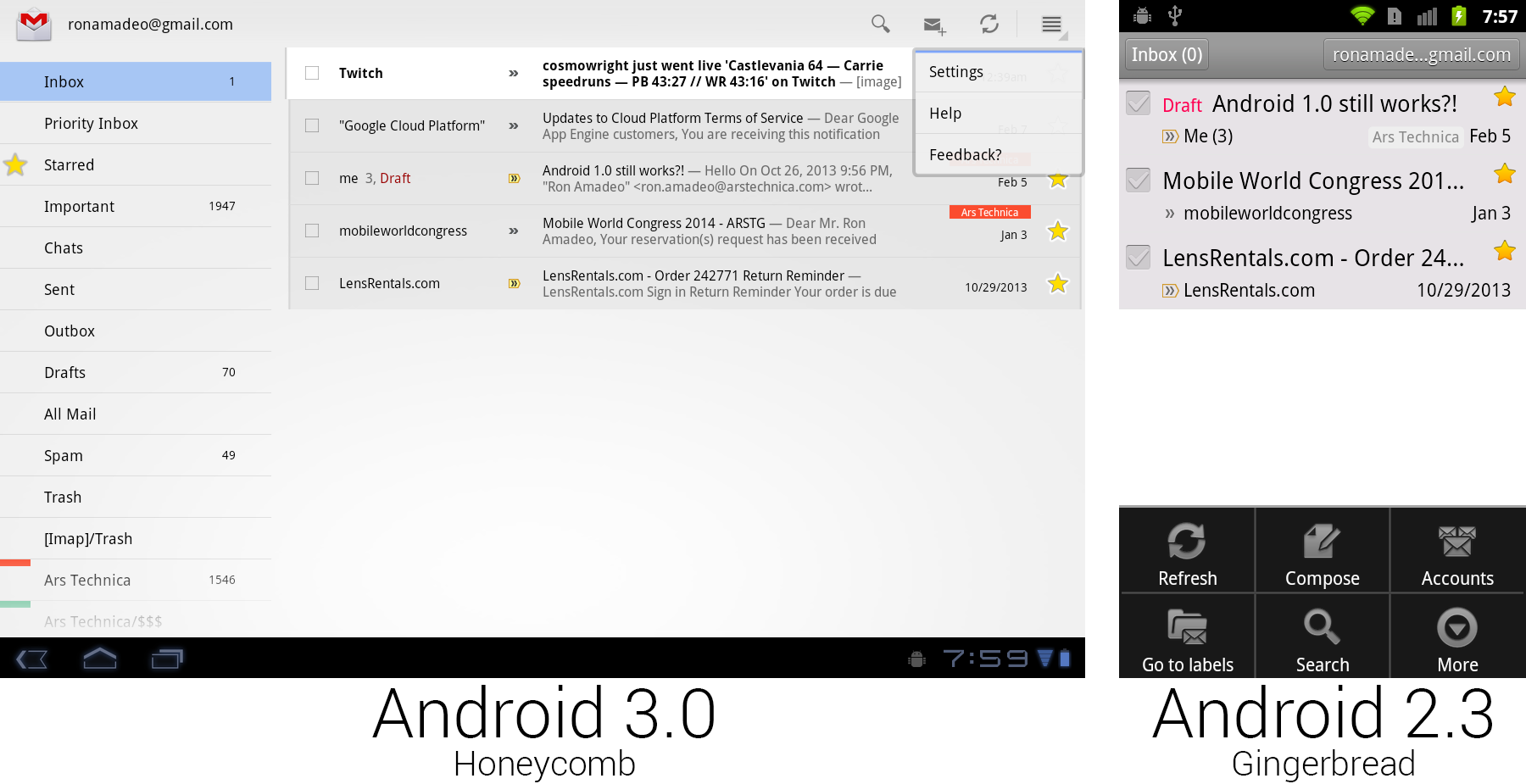

- [Android 2.3 Gingerbread—the first major UI overhaul][24]

|

||||

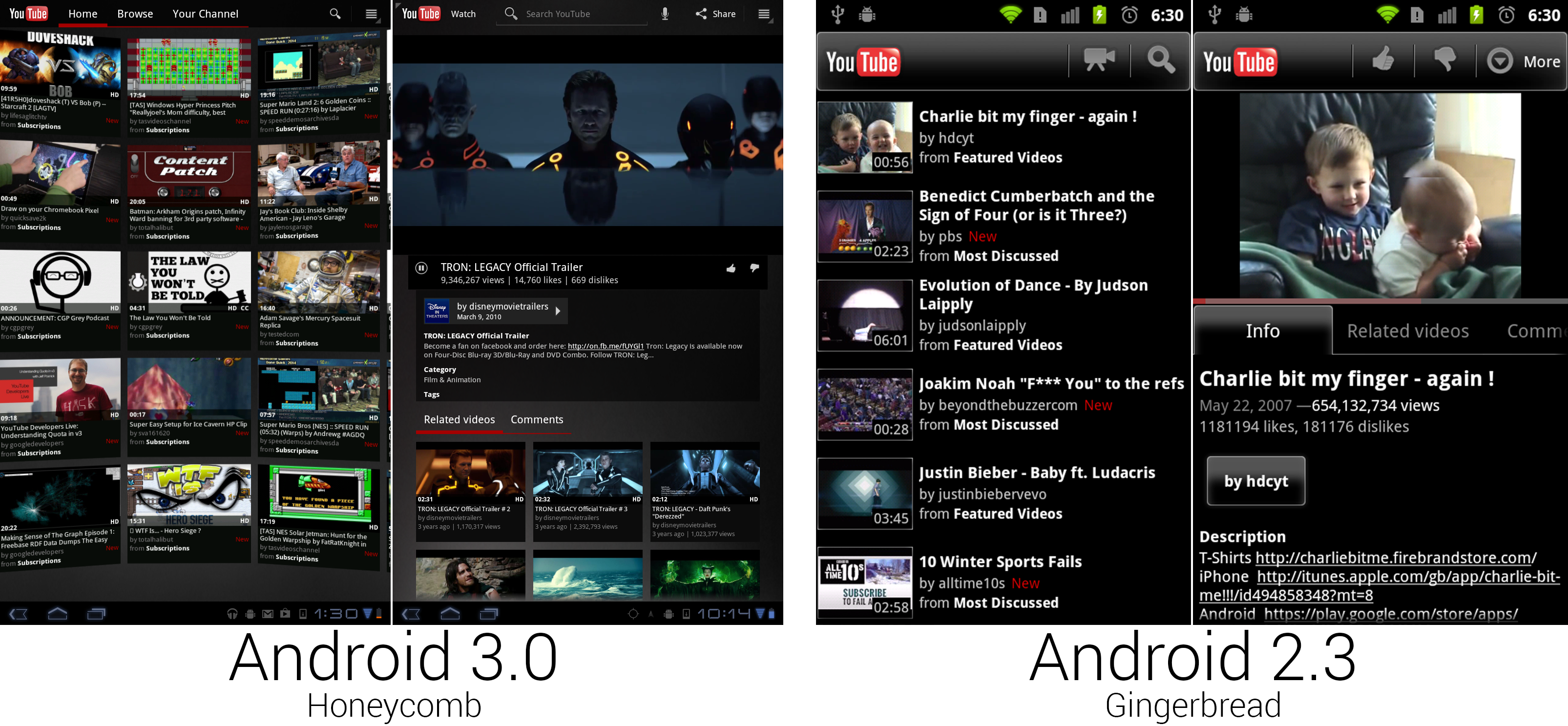

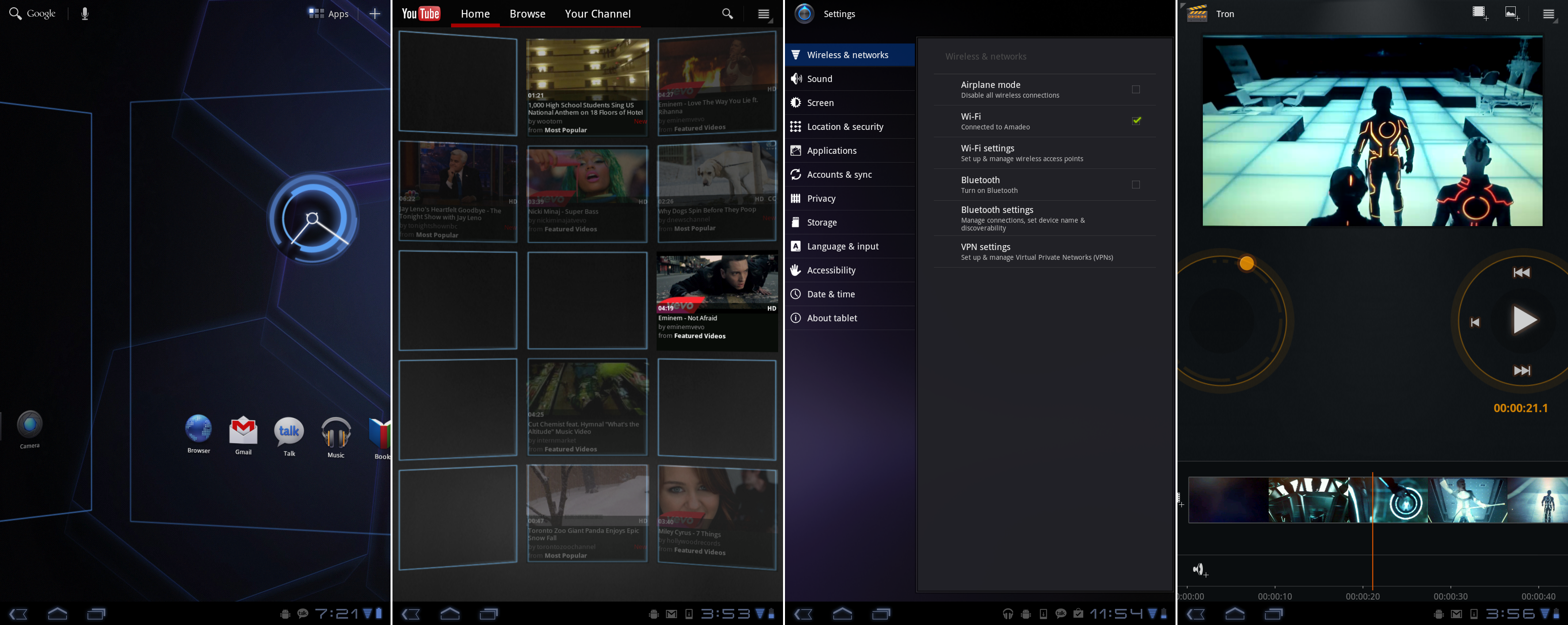

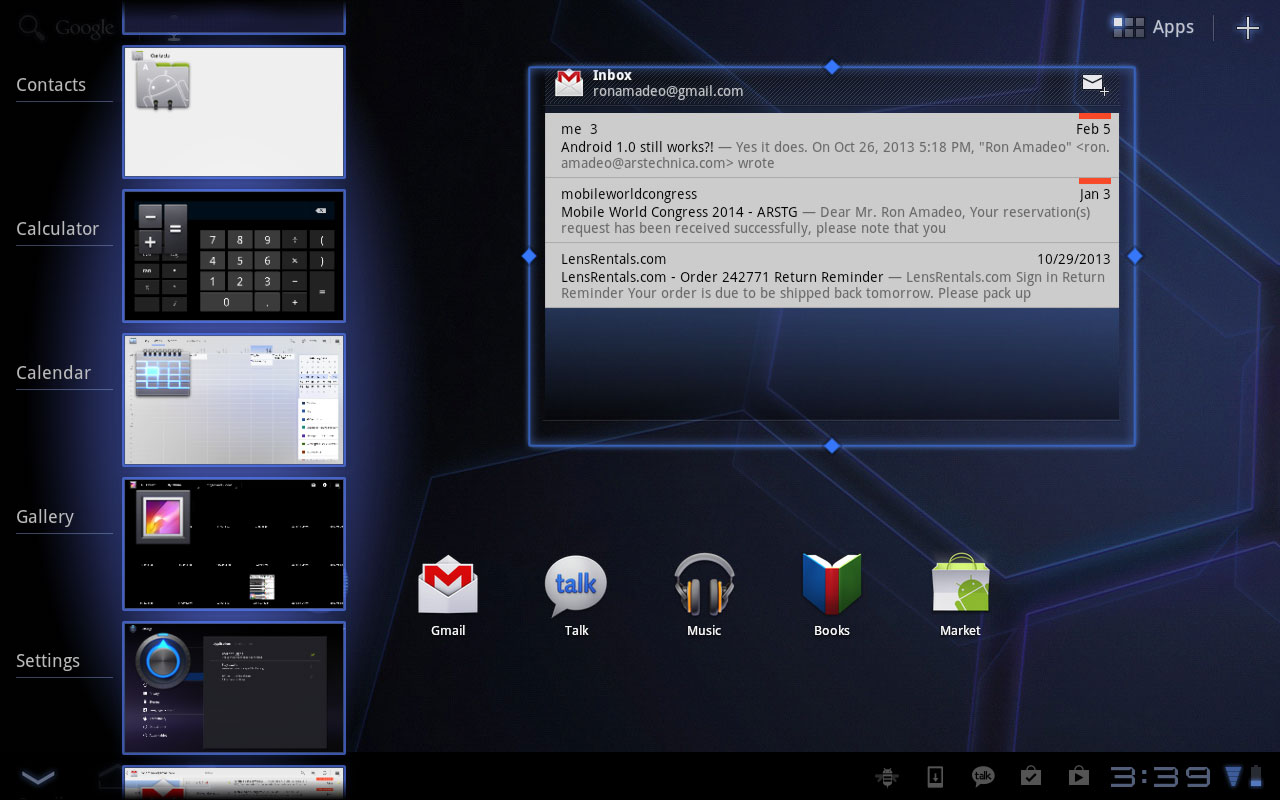

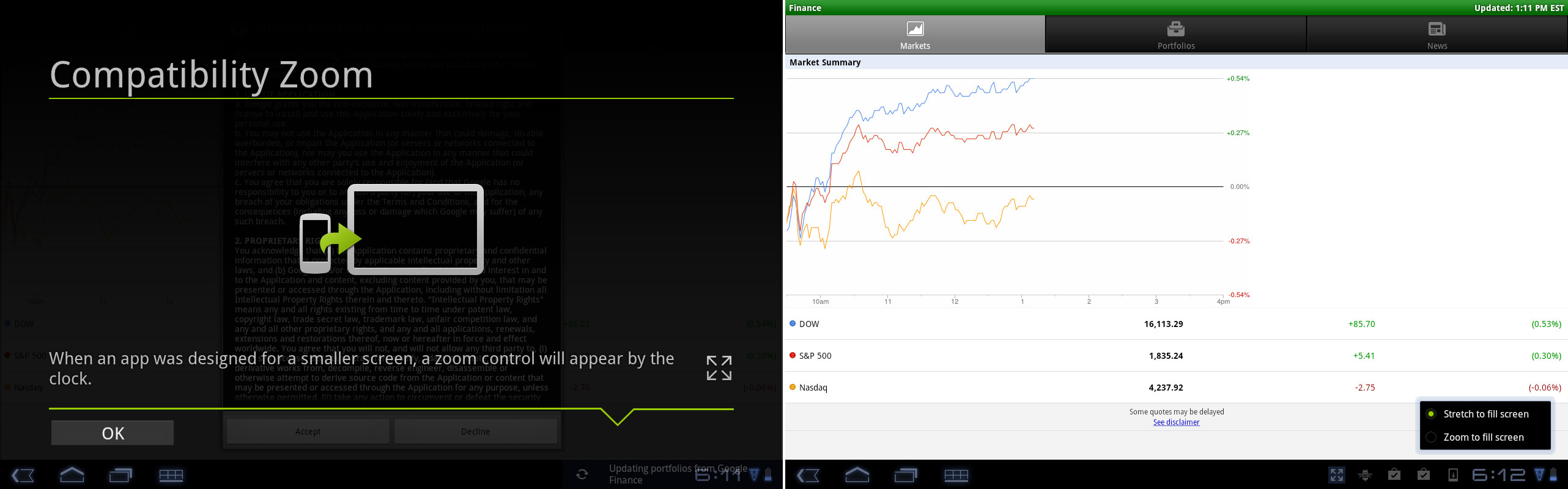

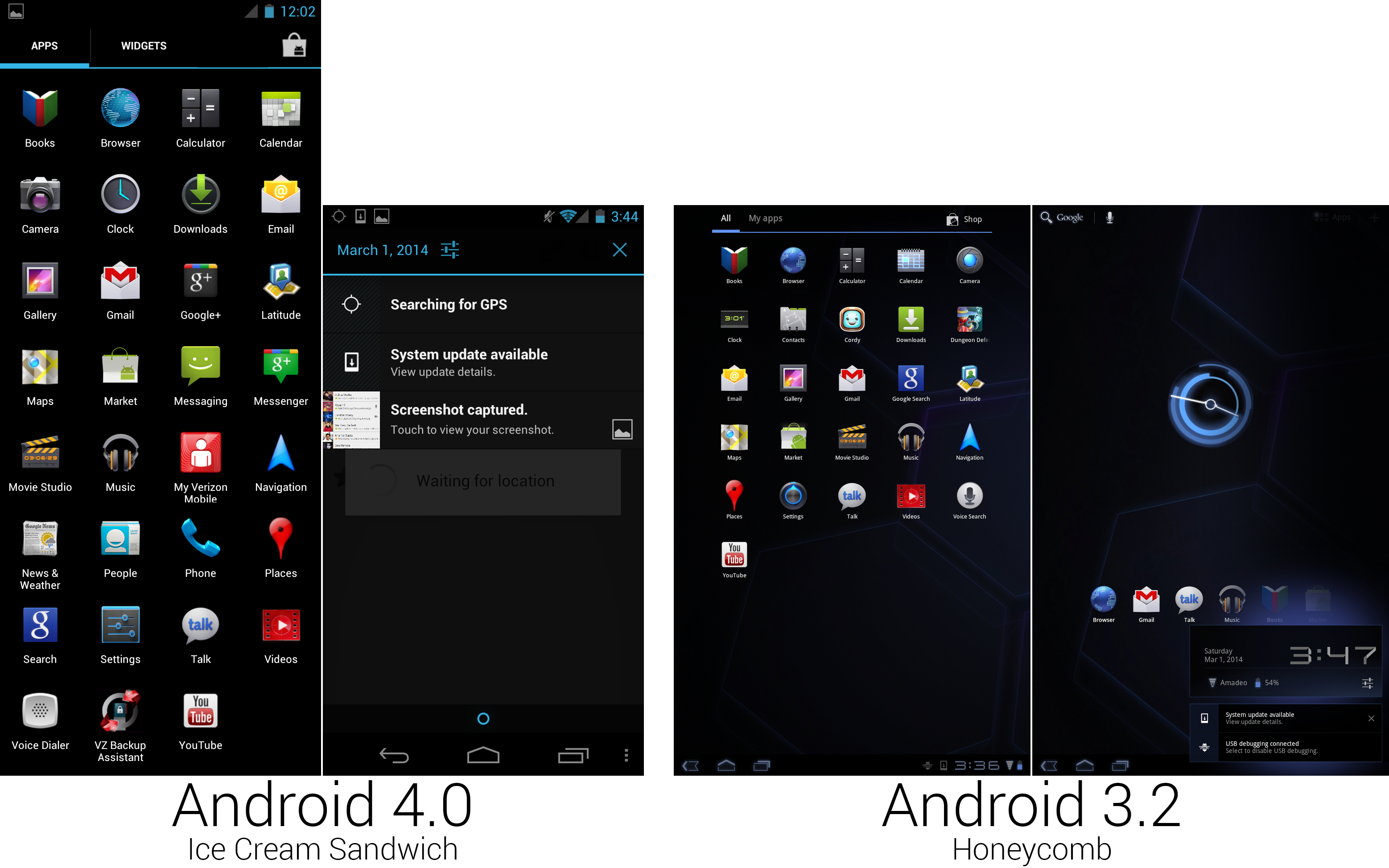

- [Android 3.0 Honeycomb—tablets and a design renaissance][25]

|

||||

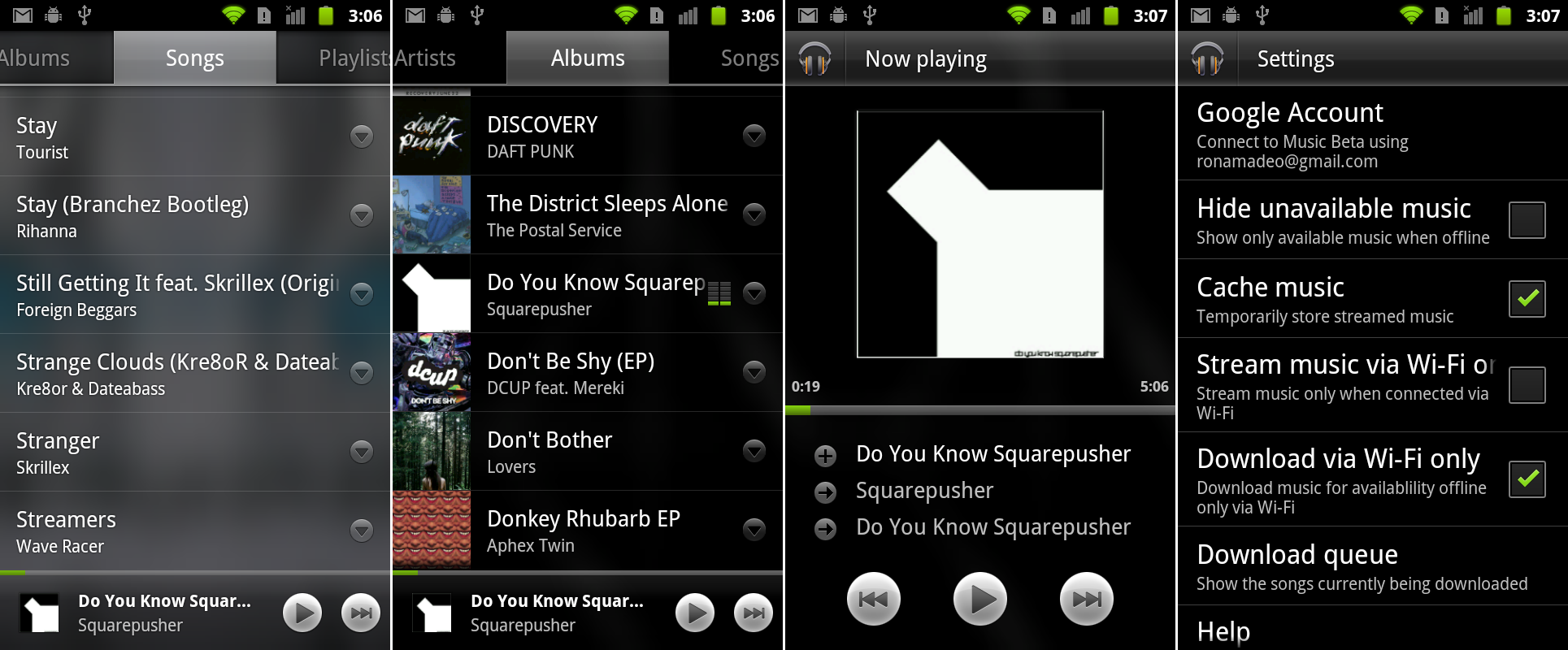

- ----[Google Music Beta—cloud storage in lieu of a content store][26]

|

||||

- [Android 4.0 Ice Cream Sandwich—the modern era][27]

|

||||

- ----[Google Play and the return of direct-to-consumer device sales][28]

|

||||

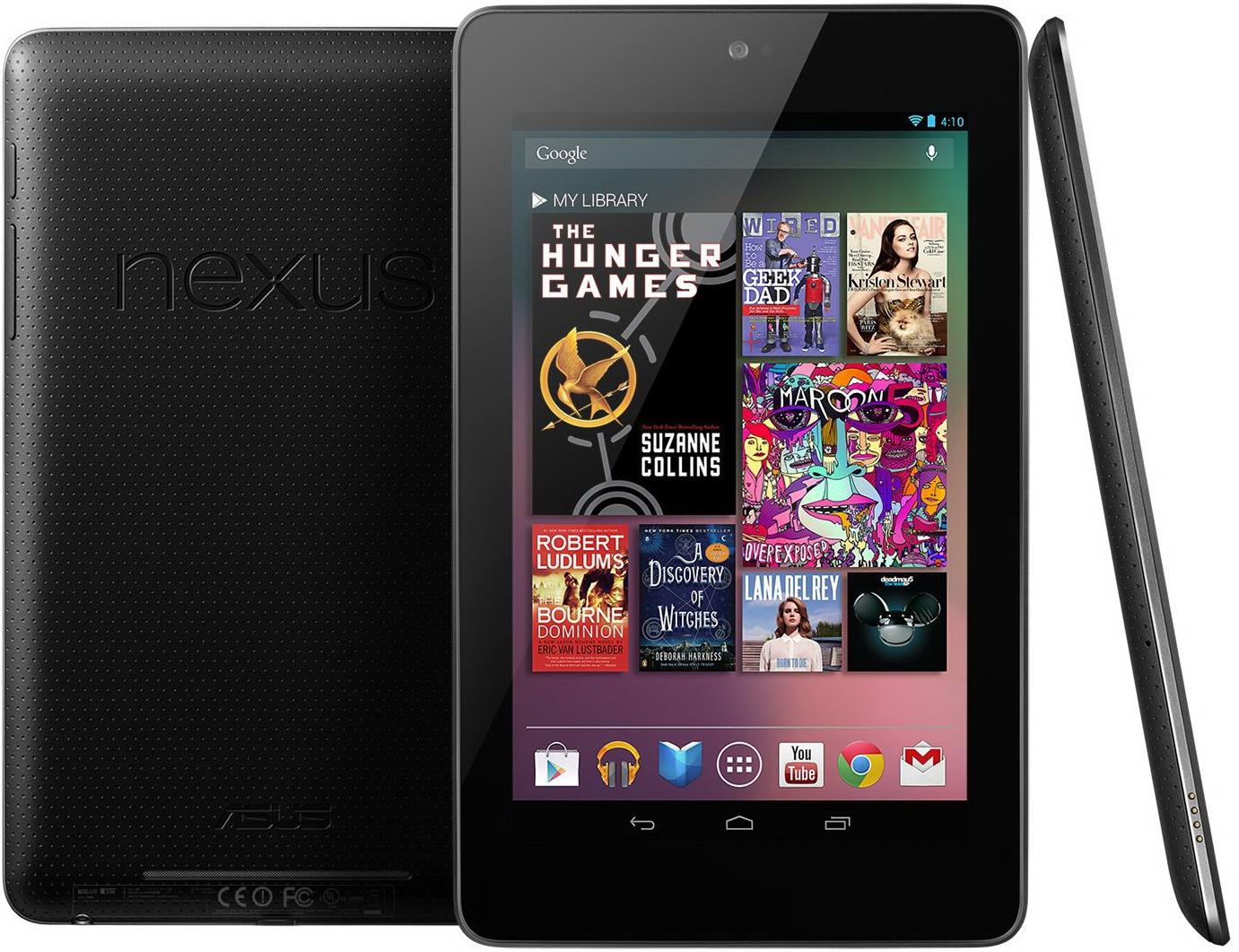

- [Android 4.1 Jelly Bean—Google Now points toward the future][29]

|

||||

- ----[Google Play Services—fragmentation and making OS versions (nearly) obsolete][30]

|

||||

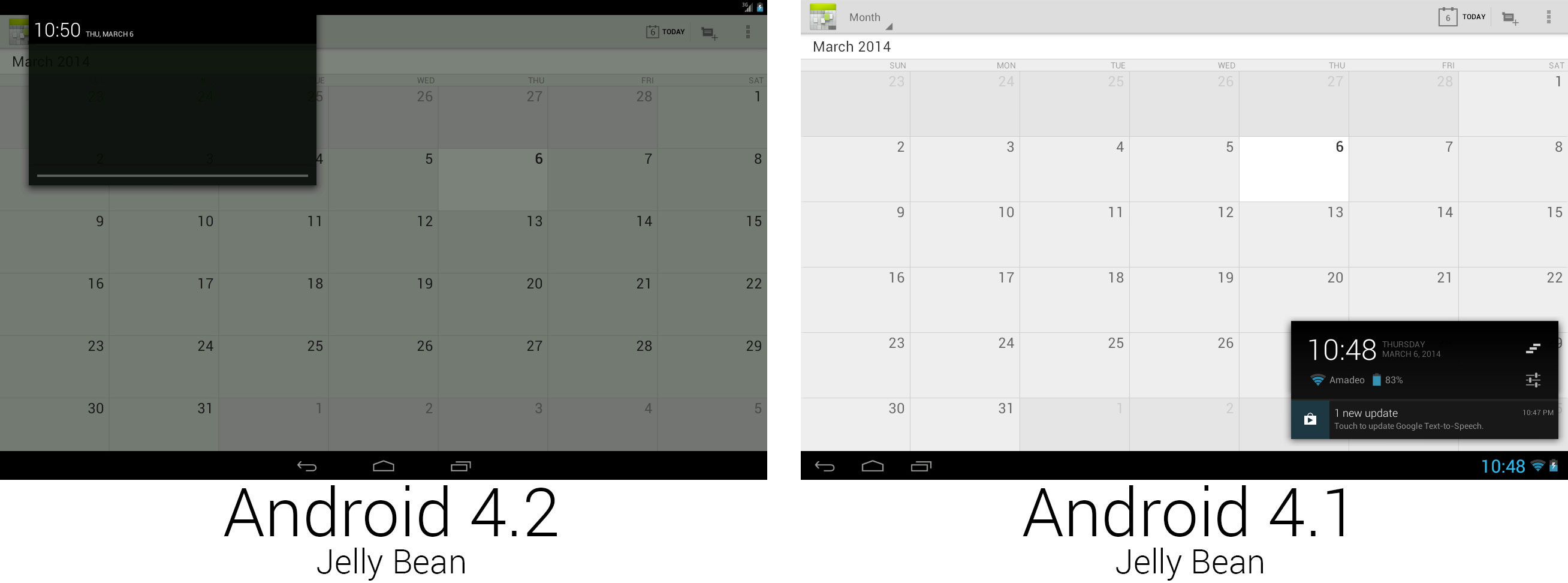

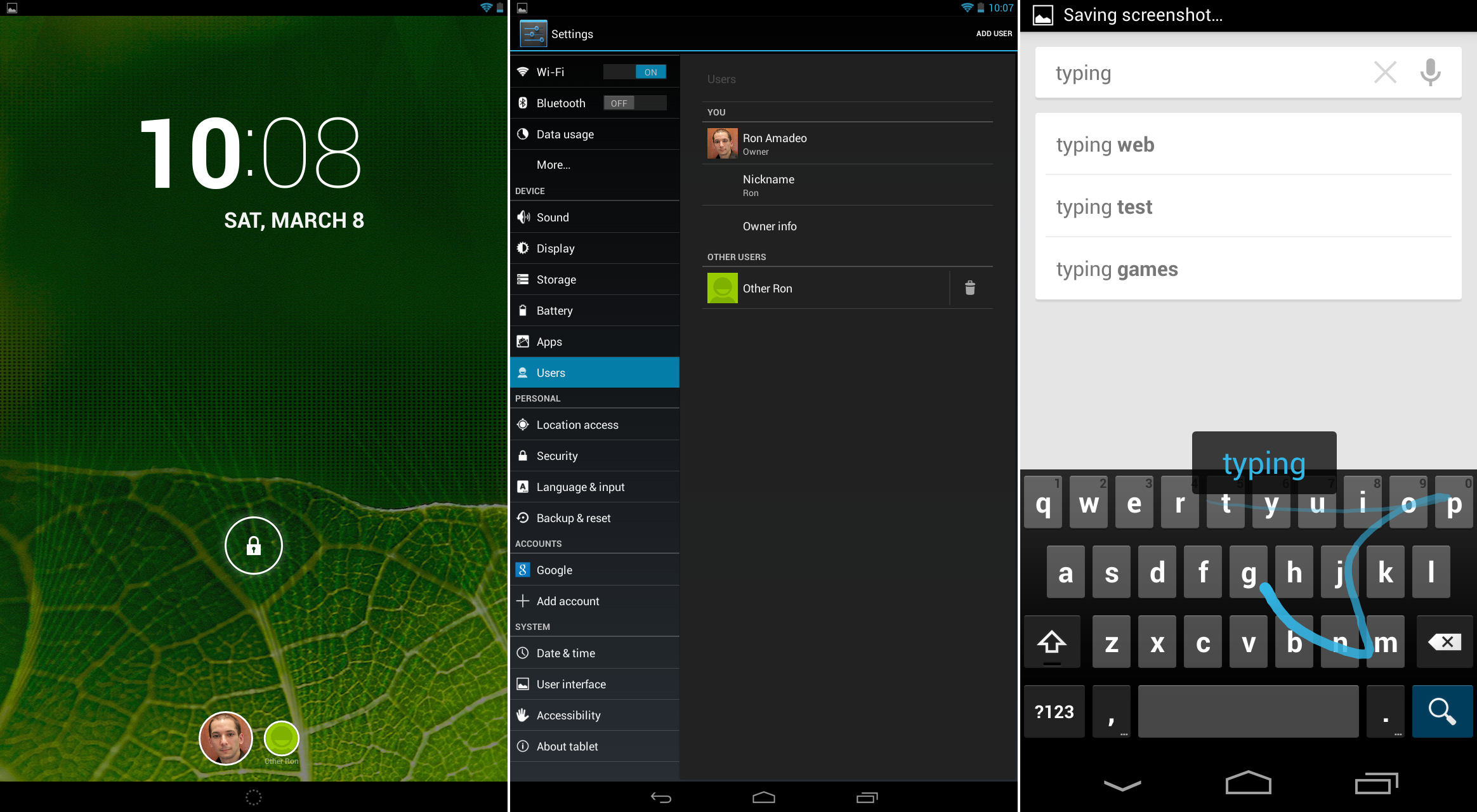

- [Android 4.2 Jelly Bean—new Nexus devices, new tablet interface][31]

|

||||

- ----[Out-of-cycle updates—who needs a new OS?][32]

|

||||

- [Android 4.3 Jelly Bean—getting wearable support out early][33]

|

||||

- [Android 4.4 KitKat—more polish; less memory usage][34]

|

||||

- [Today Android everywhere][35]

|

||||

|

||||

----------

|

||||

|

||||

### Android 0.5, Milestone 3—the first public build ###

|

||||

|

||||

Before we go diving into Android on real hardware, we're going to start with the early, early days of Android. While 1.0 was the first version to ship on hardware, there were several beta versions only released in emulator form with the SDK. The emulators were meant for development purposes only, so they don’t include any of the Google Apps, or even many core OS apps. Still, they’re our best look into the pre-release days of Android.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The emulator’s default qwerty-bar layout running the Milestone 3 build.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

Before whimsical candy code names and [cross-promotional deals with multinational food corporations][2], the first public release of Android was labeled "m3-rc20a"—"m3" standing for "Milestone 3." While Google may not have publicized the version number—and this build didn't even have a settings app to check—the browser user agent identifies this as "Android 0.5."

|

||||

|

||||

In November 2007, two years after Google acquired Android and five months after the launch of the iPhone, [Android was announced][3], and the first emulator was released. Back then, the OS was still getting its feet under it. It was easily dismissed as "just a BlackBerry clone." The emulator used a qwerty-bar skin with a 320x240 display, replicating an [actual prototype device][4]. The device was built by HTC, and it seems to be the device that was codenamed "Sooner" according to many early Android accounts. But the Sooner was never released to market.

|

||||

|

||||

[According to accounts][5] of the early development days of Android, when Apple finally showed off its revolutionary smartphone in January 2007, Google had to "start over" with Android—including scrapping the Sooner. Considering the Milestone 3 emulator came out almost a year after Apple's iPhone unveiling, it's surprising to see the device interface still closely mimicked the Blackberry model instead. While work had no doubt been done on the underlying system during that year of post-iPhone development, the emulator still launched with what was perceived as an "old school" interface. It didn't make a good first impression.

|

||||

|

||||

At this early stage, it seems like the Android button layout had not been finalized yet. While the first commercial Android devices would use “Home," “Back," “Menu," and “Search" as the standard set of buttons, the emulator had a blank space marked as an "X" where you would expect the search button to be. The “Sooner" hardware prototype was even stranger—it had a star symbol as the fourth button.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

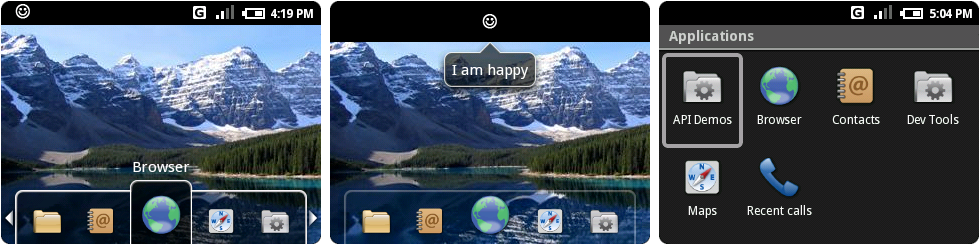

From left to right: the home screen, an open notification, and the “apps" folder.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

There was no configurable home screen or widgets, just a simple dock of icons at the bottom that could be cycled through or tapped on. While touch screen support worked for some features, Milestone 3 was primarily controlled with a five-way d-pad—an anachronism that Android still supports to this day. Even this early version of Android could do animations. Icons would grow and shrink as they entered and exited the dock’s center window.

|

||||

|

||||

There was no notification panel yet, either. Notification icons showed up in the status bar (shown above as a smiley face), and the only way to open them was to press "up" on the d-pad while on the home screen. You couldn't tap on the icon to open it, nor could you access notifications from any screen other than home. When a notification was opened, the status bar expanded slightly, and the text of the notification appeared in a speech bubble. Once you had a notification, there was no manual way to clear it—apps were responsible for clearing their own notifications.

|

||||

|

||||

App drawer duties were handled by a simple "Applications" folder on the left of the dock. Despite having a significant amount of functions, the Milestone 3 emulator was not very forthcoming with app icons. "Browser," "Contacts," and "Maps" were the only real apps here. Oddly, "recent calls" was elevated to a standalone icon. Because this was just an emulator, icons for core smartphone functionality were missing, like alarm, calendar, dialer, calculator, camera, gallery, and settings. Hardware prototypes demoed to the press had [many of these][6], and there was a suite of Google Apps up and running by this point. Sadly, there’s no way for us to look at them. They’re so old they can't connect to Google’s servers now anyway.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

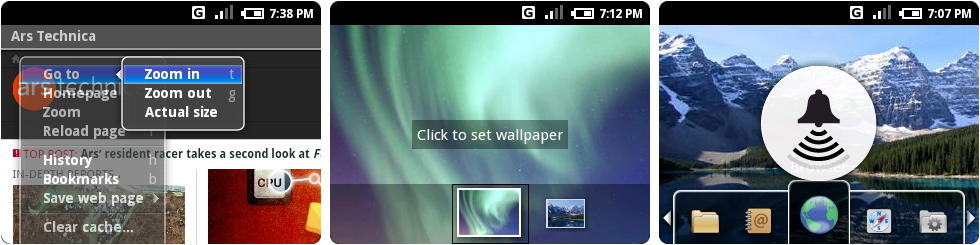

Milestone 3's menu system in the browser, the wallpaper interface, and the volume control.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

The now-deprecated menu system was up and running in Milestone 3. Hitting the hardware menu button brought up a gray list with a blue gradient highlight, complete with hardware keyboard shortcuts. In the screenshot above, you can see the menu open in the browser. Going to a second level, like the zoom menu, turned the first level of the menu oddly transparent.

|

||||

|

||||

Surprisingly, multitasking and background applications already worked in Milestone 3. Leaving an app didn't close it—apps would save state, even down to text left in a text box. This was a feature iOS wouldn’t get around to matching until the release of iOS 4 in 2010, and it really showed the difference between the two platforms. iOS was originally meant to be a closed platform with no third-party apps, so the platform robustness wasn’t a huge focus. Android was built from the ground up to be a powerful app platform, and ease of app development was one of the driving forces behind its creation.

|

||||

|

||||

Before Android, Google was already making moves into mobile with [WAP sites][7] and [J2ME flip phone apps][8], which made it acutely aware of how difficult mobile development was. According to [The Atlantic][9], Larry Page once said of the company’s mobile efforts “We had a closet full of over 100 phones, and we were building our software pretty much one device at a time.” Developers often complain about Android fragmentation now, but the problem was much, much worse before the OS came along.

|

||||

|

||||

Google’s platform strategy eventually won out, and iOS ended up slowly adding many of these app-centric features—multitasking, cross-app sharing, and an app switcher—later on.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

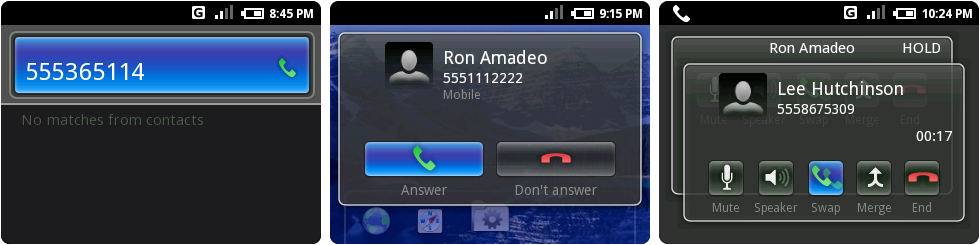

The dialer screen that pops up when you press numbers on the home screen, an incoming call, and the call conferencing interface.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

Despite not having a dialer icon, Milestone 3 emulator was equipped with a way to make phone calls. Pressing anything on the keyboard would bring up the screen on the left, which was a hybrid dialer/contact search. Entering only numbers and hitting the green phone hardware button would start a phone call, and letters would search contacts. Contacts were not searchable by number, however. Even a direct hit on a phone number would not bring up a contact.

|

||||

|

||||

Incoming calls were displayed as an almost-full-screen popup with a sweet transparent background. Once inside a call, the background became dark gray, and Milestone 3 presented the user with a surprisingly advanced feature set: mute, speakerphone, hold, and call conferencing buttons. Multiple calls were presented as overlapping, semi-transparent cards, and users had options to swap or merge calls. Swapping calls triggered a nice little card shuffle animation.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

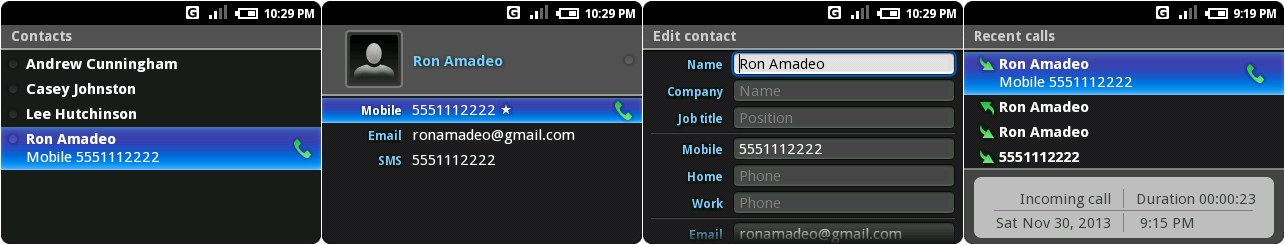

The contacts list, an individual contact, editing a contact, and the recent calls screen.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

Contacts was a stark, black and blue list of names. Contact cards had a spot for a contact picture but couldn't assign one to the space (at least in the emulator). The only frill in this area was XMPP presence dots to the left of each name in Contacts. An always-on XMPP connection has traditionally been at the heart of Android, and that deep integration already started in Milestone 3. Android used XMPP to power a 24/7 connection to Google’s servers, powering Google Talk, cloud-to-device push messaging, and app install and uninstall messages.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

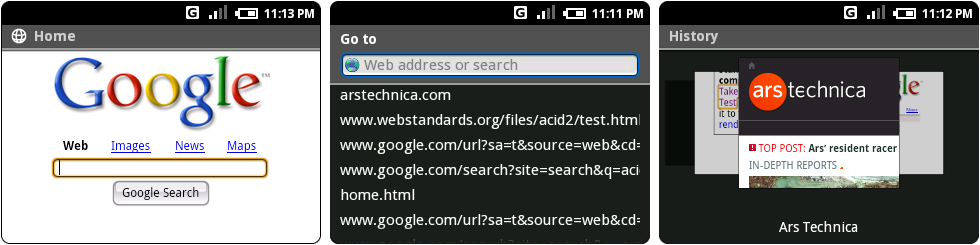

The browser’s fake Google homepage, the address bar, and the history interface.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

The browser ran Webkit 419.3, which put it in the same era as Mac OS X 10.4's Safari 2. The homepage was not Google.com, but a hard-coded home.html file included with Android. It looked like Google.com from a thousand years ago. The browser's OS X heritage was still visible, rendering browser buttons with a glossy, Aqua-style search button.

|

||||

|

||||

The tiny BlackBerry-style screen necessitated a separate address bar, which was brought up by a "go to" option in the browser's menu. While autocomplete didn't work, the address bar live searched your history as you typed. The picture on the right was the History display, which used thumbnails to display each site. The current thumbnail was in front of the other two, and scrolling through them triggered a swooping animation. But at this early stage, the browser didn’t support multiple tabs or windows—you had the current website, and that was it.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

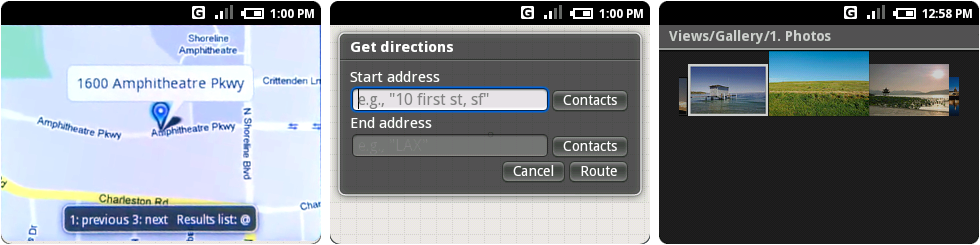

A video-screengrab-derived Google Maps Photoshop, the directions interface, and the gallery test view.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

From the beginning, Google knew maps would be important on mobile, even shipping a Maps client on the Milestone 5 emulator. That version of Google Maps was the first thing we came across that died from cloud rot. The client can't load information from Google’s servers, so the map displayed as a blank, gray grid. Nothing works.

|

||||

|

||||

Luckily, for the first screenshot above, we were able to piece together an accurate representation from the Android launch video. Old Google Maps seemed fully prepared for a non-touch device, listing hardware key shortcuts along the bottom of the screen. It’s unclear if places worked, or if Maps only ran on addresses at this point.

|

||||

|

||||

Hidden behind the menu were options for search, directions, and satellite and traffic layers. The middle screenshot is of the directions UI, where you could even pick a contact address as a start or end address. Maps lacked any kind of GPS integration, however; you can't find a "my location" button anywhere.

|

||||

|

||||

While there was no proper gallery, on the right is a test view for a gallery, which was hidden in the "API Demos" app. The pictures scrolled left and right, but there was no way to open photos to a full screen view. There were no photo management options either. It was essentially a test of a scrolling picture view.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

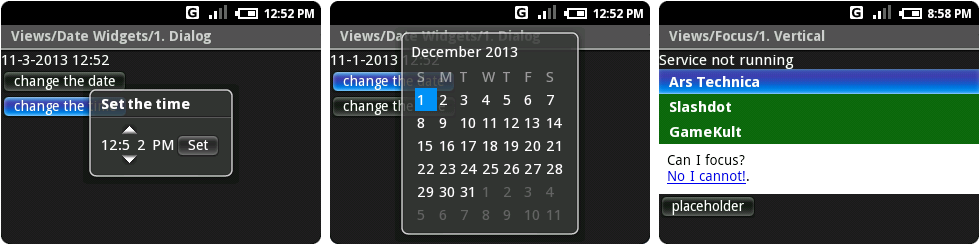

The time picker and calendar, with ridiculous kerning issues, and the vertical list test, featuring Ars.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

There was also no settings app, but we can look at the original time and date pickers, thanks to the API Demos. This demonstrates how raw a lot of Android was: kerning issues all over the place, a huge gap in between the minute digits, and unevenly spaced days of the week on the calendar. While the time picker let you change each digit independently, there was no way to change months or years other than moving the day block out of the current month and on to the next or previous month.

|

||||

|

||||

Keep in mind that while this may seem like dinosaur remnants from some forgotten era, this was only released six years ago. We tend to get used to the pace of technology. It's easy to look back on stuff like this and think that it was from 20 years ago. Compare this late-2007 timeframe to desktop OSes, and Microsoft was trying to sell Windows Vista to the world for almost a year, and Apple just released OS X 10.5 Leopard.

|

||||

|

||||

One last Milestone 3 detail: Google gave Ars Technica a shoutout in the Milestone 3 emulator. Opening the “API Demos" app and going to "Views," "Focus," then "Vertical" revealed a test list headlined by *this very Website*.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The new emulator skin that comes with Milestone 3, RC37a, which uses a more modern, all-touchscreen style.

|

||||

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

Two months later, in December 2007, Google released an update for the Milestone 3 emulator that came with a much roomier 480×320 device configuration. This was tagged "m3-rc37a." The software was still identical to the BlackBerry build, just with much more screen real estate available.

|

||||

|

||||

----------

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

[Ron Amadeo][a] / Ron is the Reviews Editor at Ars Technica, where he specializes in Android OS and Google products. He is always on the hunt for a new gadget and loves to rip things apart to see how they work.

|

||||

|

||||

[@RonAmadeo][t]

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/

|

||||

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID) 校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创翻译,[Linux中国](http://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[1]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/how-we-found-and-installed-every-version-of-android/

|

||||

[2]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2013/09/official-the-next-edition-of-android-is-kitkat-version-4-4/

|

||||

[3]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2007/11/its-official-google-announces-open-source-mobile-phone-os-android/

|

||||

[4]:http://www.zdnet.com/blog/mobile-gadgeteer/mwc08-hands-on-with-a-working-google-android-device/860

|

||||

[5]:http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/12/the-day-google-had-to-start-over-on-android/282479/

|

||||

[6]:http://www.letsgomobile.org/en/2974/google-android/

|

||||

[7]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/%E2%80%9D

|

||||

[8]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/%E2%80%9D

|

||||

[9]:http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2013/12/the-day-google-had-to-start-over-on-android/282479/

|

||||

[10]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/1/#milestone3

|

||||

[11]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/2/#milestone5

|

||||

[12]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/3/#0.9

|

||||

[13]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/6/#1.0

|

||||

[14]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/7/#1.1

|

||||

[15]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/8/#cupcake

|

||||

[16]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/9/#Mapsmarket

|

||||

[17]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/9/#donut

|

||||

[18]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/10/#2.0eclair

|

||||

[19]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/11/#nexusone

|

||||

[20]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/12/#2.1eclair

|

||||

[21]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/13/#alloutwar

|

||||

[22]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/13/#froyo

|

||||

[23]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/14/#voiceactions

|

||||

[24]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/14/#gingerbread

|

||||

[25]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/16/#honeycomb

|

||||

[26]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/19/#music

|

||||

[27]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/19/#ics

|

||||

[28]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/21/#googleplay

|

||||

[29]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/21/#4.1jellybean

|

||||

[30]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/21/#playservices

|

||||

[31]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/22/#4.2jellybean

|

||||

[32]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/23/#outofcycle

|

||||

[33]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/24/#4.3jellybean

|

||||

[34]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/25/#kitkat

|

||||

[35]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/26/#conclusion

|

||||

[a]:http://arstechnica.com/author/ronamadeo

|

||||

[t]:https://twitter.com/RonAmadeo

|

||||

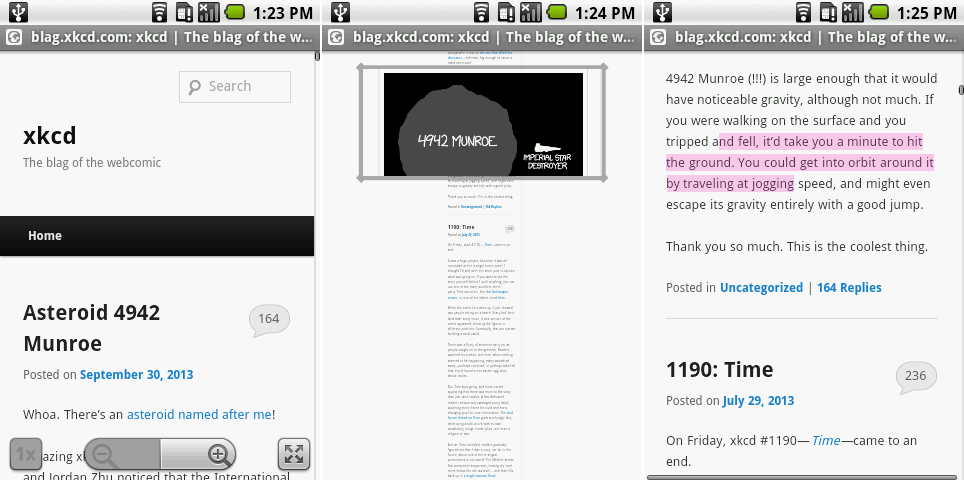

@ -0,0 +1,78 @@

|

||||

The history of Android

|

||||

================================================================================

|

||||

|

||||

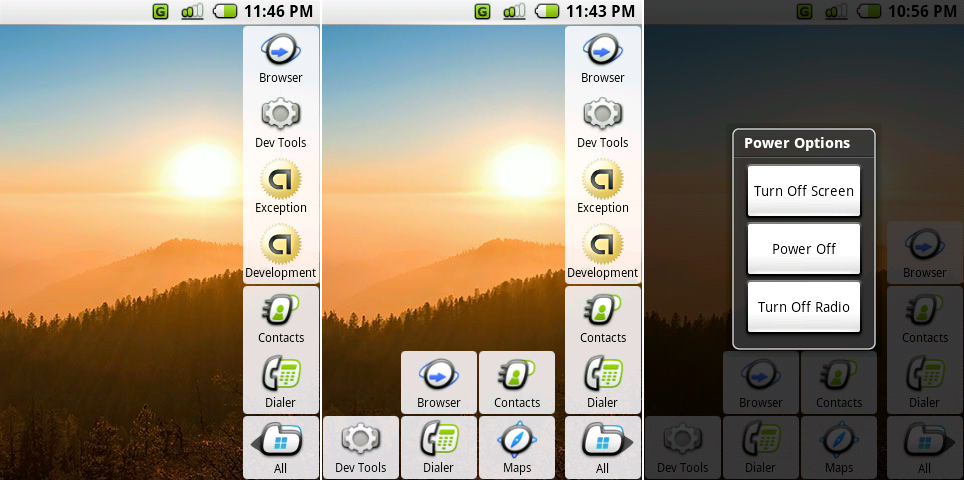

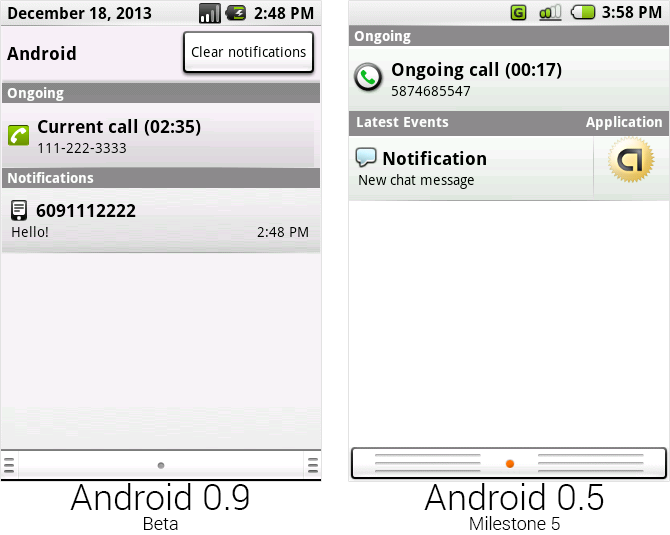

Left: the Milestone 5 home screen showing the “all" button, two dock icons, and four recent apps. Center: the home screen with the app list open. Right: the power menu.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

### Android 0.5, Milestone 5—the land of scrapped interfaces ###

|

||||

|

||||

The first major Android change came three months after the first emulator release: the "m5-rc14" build. Released in February 2008, “Milestone 5" dumped the stretched-out BlackBerry interface and went with a totally revamped design—Google's first attempt at a finger-friendly interface.

|

||||

|

||||

This build was still identified as "Android 0.5" in the browser user agent string, but Milestone 5 couldn't be more different from the first release of Android. Several core Android features can directly trace their lineage back to this version. The layout and functionality of the notification panel was almost ready to ship, and, other than a style change, the menu was present in its final form, too. Android 1.0 was only eight months away from shipping, and the basics of an OS were starting to form.

|

||||

|

||||

One thing that was definitely not in its final form was the home screen. It was an unconfigurable, single-screen wallpaper with an app drawer and dock. App icons were bubbly, three-color affairs, surrounded by a square, white background with rounded corners. The app drawer consisted of an "All" button in the lower-right corner, and tapping on it expanded the list of apps out to the left. Above the "All" button was a two icon dock where "Contacts" and "Dialer" were given permanent home screen real estate. The four blocks above that were an early version of Recent Apps, showing the last apps accessed. With no left or right screens and a whole column taken up by the dock and recent apps, this layout only allowed for 21 app squares before the screen would be filled. The emulator still only sported the bare-minimum app selection, but in an actual device, this design didn't appear like it would work well.

|

||||

|

||||

Holding down the "end call" button brought up a super early version of the power menu, which you can see in the rightmost picture. Google didn't have the normal smartphone nomenclature down yet: "Turn Off Screen" would best be described as "Lock screen" (although there was no lock screen) and "Turn Off Radio" would be called "Airplane mode" today.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

From left to right: the surprisingly modern notification panel, the menu open in Google Maps (Maps doesn't work anymore), and the new finger-friendly list view.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

All the way back in Milestone 5, Google had the basics of the notification panel nailed down. It pulled down from the top of the screen just like it does on any modern smartphone. Current notifications displayed in a list. The first version of the notification panel was an opaque white sheet with a ribbed “handle" on the bottom and an orange dot in the center. Notifications were pressable, opening the appropriate app for that notification. No one bothered to vertically align the app icons in this list, but that's OK. This was gone in the next update.

|

||||

|

||||

Sticky notifications went into an "ongoing" section at the top of the panel. In this build, that seemed to only include phone calls. The "Latest Event" notifications were clearable only after opening the appropriate app. Users surprisingly managed to sign in to Google Talk over the built-in XMPP connection. But while the notification panel displayed "new chat message," there wasn't actually an instant messaging app.

|

||||

|

||||

The artwork in Milestone 5 was all new. The app icons were redrawn, and the menu switched from a boring BlackBerry-style text list to full-color, cartoony icons on a large grid. The notification panel icons switched from simple, sharp, white icons to a bubbly green design. There was now a strange black line under the signal bar indicator with no apparent purpose. The tiny list view from earlier builds really wasn't usable with a finger, so Milestone 5 came with an overall beefier layout.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

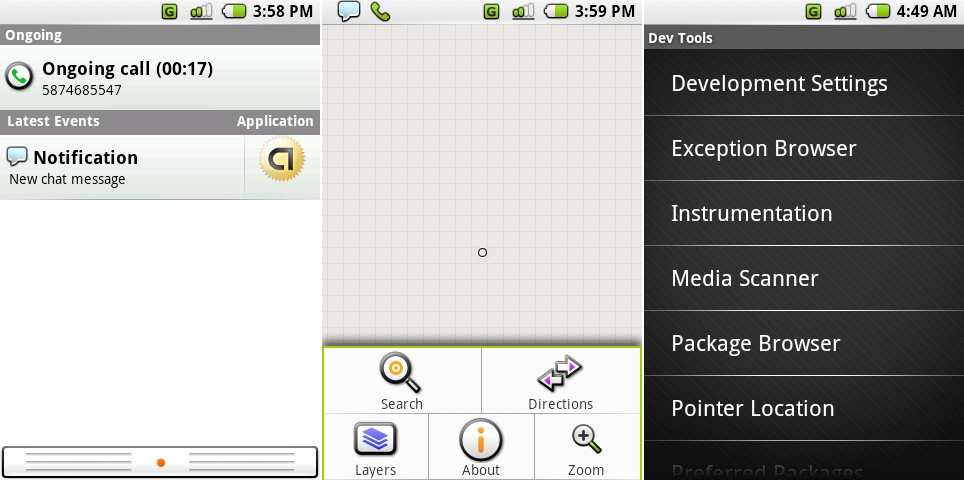

The dialer, recent calls, and an incoming call.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

M5 was the first build to have a dialer, albeit a fairly ugly one. Numbers were displayed in a gradient-filled bar containing a bizarre speech-bubble-styled backspace button that looked like it was recycled from some other interface. Alignment issues were everywhere. The numbers on the buttons weren't vertically aligned correctly, and the “X" in the backspace button wasn’t aligned with the speech bubble. You couldn't even start a call from the dialer—with no on-screen “dial" button, a hardware button was mandatory.

|

||||

|

||||

Milestone 5 had a few tabbed interfaces, all of which demonstrated an extremely odd idea of how tabs should work. The active tab was white, and the background tabs were black with a tiny strip of white at the bottom. Were background tabs supposed to "shrink" downward? There was no animation when switching tabs. It wasn't clear what the design tried to communicate.

|

||||

|

||||

Recent Calls, shown in the second picture, was downgraded from a top-tier app to a tab on the dialer. It ditched the crazy crosshair UI from earlier builds and, thanks to the chunkier list view, now displayed all the necessary information in a normal list.

|

||||

|

||||

Unlike the dialer, the incoming call screen had on-screen buttons for answering and ending a call. Bizarrely, the incoming call screen was stuck to the bottom of the display, rather than the top or center. It was possibly left over from the old 4:3 BlackBerry screens.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

An active call, the disabled touchscreen error message, and the call screen with a second call on hold.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

The in-call interface looked normal but made zero sense in practice. Today, to stop your face from pressing buttons while on a call, phones have proximity sensors that turn the screen off when the sensor detects something. Milestone 5 didn’t support proximity sensors, though. Google’s haphazard solution was to disable the entire touch screen during a call. At the same time, the in-call screen was clearly overhauled for touch. There were big, finger-friendly buttons; *you just couldn't touch anything*.

|

||||

|

||||

M5 featured a few regressions here from the old Milestone 3 build. Many decent-looking icons from the old interface were replaced with text. Buttons like "mute" no longer offered on-screen feedback that they were active. Merging calls was cut completely.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The browser’s primary menu, the browser’s secondary menu, the crazy zoom control, and the window interface.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

The browser menu got the usual touch overhaul, and for the first time a "more" button appeared. It functioned as an [extra menu for your menu][1]. Rather than turning the 3x2 grid into a 3x4 grid, Milestone 5 (and many successive versions of Android) used a long, scrolling list for the additional options. Pinch zoom wasn't supported (supposedly a [concession to Apple][2]), so Android went with the ridiculous looking zoom control in the third picture above. Rather than something sensible like a horizontal, bottom-aligned zoom control, Google stuck it smack in the middle of the screen. The last picture shows the Browser’s "window" interface, which allowed you to open multiple webpages and semi-easily switch between them.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

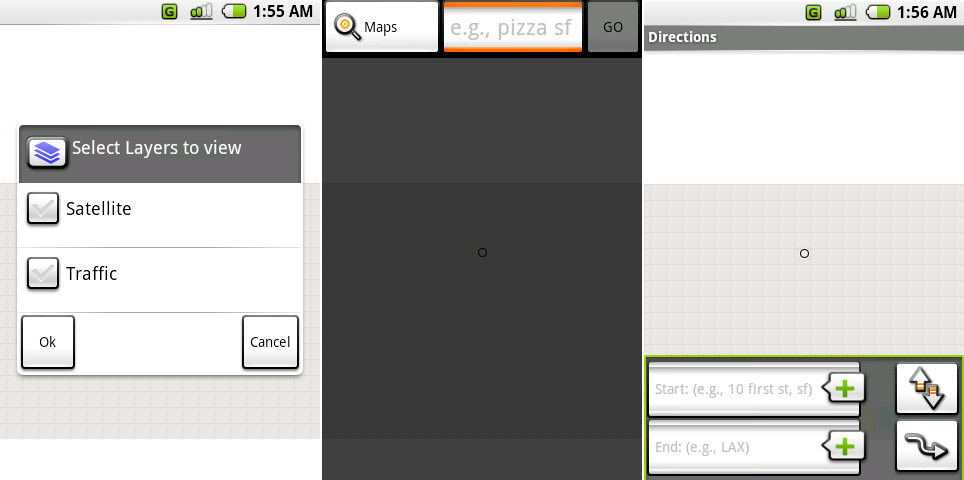

Google Maps’ layers section screen, search interface, and directions screen.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

Google Maps still didn't work, but the little UI we accessed saw significant updates. You could pick map layers, although there were only two to choose from: Satellite and Traffic. The top-aligned search interface strangely hid the status bar, while the bottom-aligned directions didn't hide the status bar. Direction's enter button was labeled with "Go," and Search's enter button was labeled with a weird curvy arrow. The list goes on and demonstrates old school Android at its worst: two functions in the same app that should look and work similarly, but these were implemented as complete opposites.

|

||||

|

||||

----------

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

[Ron Amadeo][a] / Ron is the Reviews Editor at Ars Technica, where he specializes in Android OS and Google products. He is always on the hunt for a new gadget and loves to rip things apart to see how they work.

|

||||

|

||||

[@RonAmadeo][t]

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/2/

|

||||

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID) 校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创翻译,[Linux中国](http://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[1]:http://i.imgur.com/GIYGTnb.jpg

|

||||

[2]:http://www.businessinsider.com/steve-jobs-on-android-founder-andy-rubin-big-arrogant-f-2013-11

|

||||

[a]:http://arstechnica.com/author/ronamadeo

|

||||

[t]:https://twitter.com/RonAmadeo

|

||||

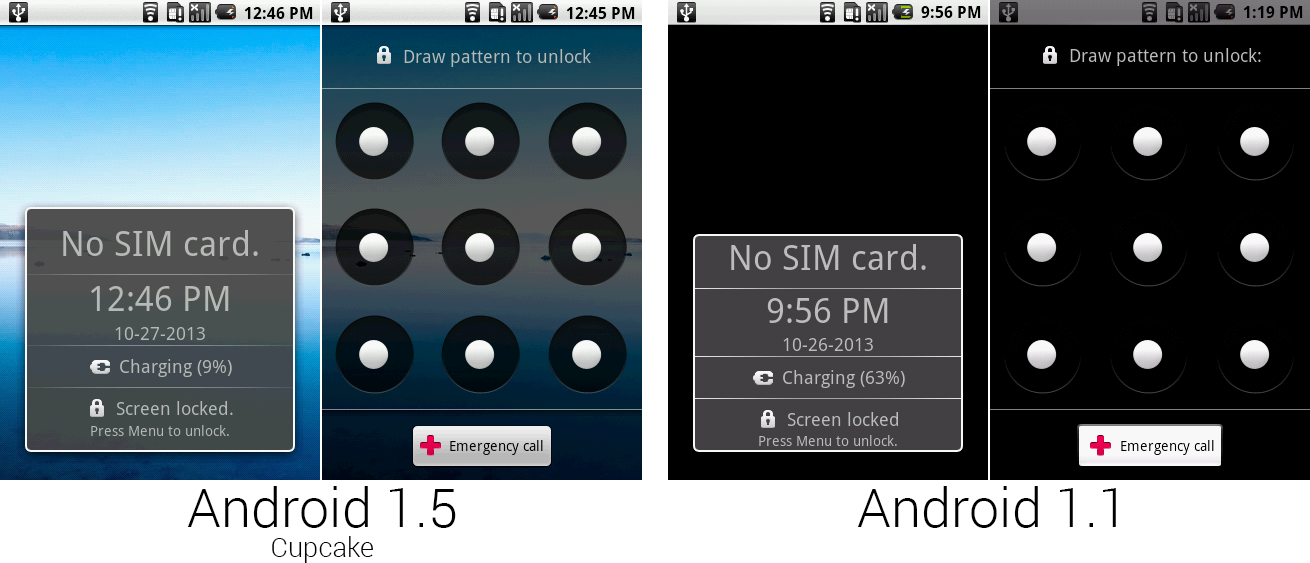

@ -0,0 +1,64 @@

|

||||

The history of Android

|

||||

================================================================================

|

||||

|

||||

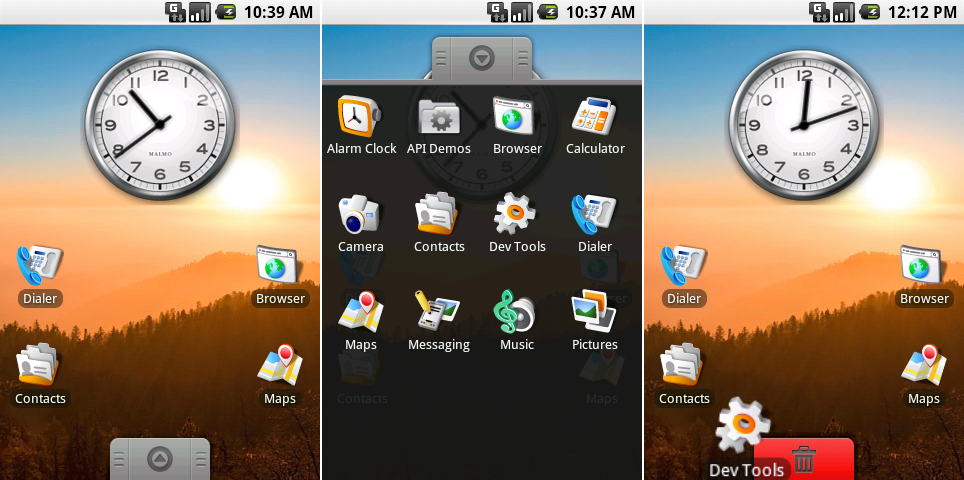

From left to right: Android 0.9’s home screen, add drawer, and shortcut deletion interfaces.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

### Android 0.9, Beta—hey, this looks familiar! ###

|

||||

|

||||

Six months after Milestone 5, in August 2008, [Android 0.9 was released][1]. While the Android 0.5 milestone builds were "early looks," by now 1.0 was only two months away. Thus, Android 0.9 was labeled "beta." On the other side of the aisle, Apple already released its second version of the iPhone—the iPhone 3G—a month prior. The second-gen iPhone brought a second-gen iPhone OS. Apple also launched the App Store and was already taking app submissions. Google had a lot of catching up to do.

|

||||

|

||||

Google threw out a lot of the UI introduced in Milestone 5. All the artwork was redone again in full-color, and the white square icon backgrounds were tossed. While still an emulator build, 0.9 offered something that looked familiar when compared to a released version of Android. Android 0.9 had a working desktop-style home screen, a proper app drawer, multiple home screens, a lot more apps, and fully functional (first-party only) widgets.

|

||||

|

||||

Milestone 5 seemingly had no plan for someone installing more than 21 apps, but Android 0.9 had a vertically scrolling app drawer accessible via a gray tab at the bottom of the screen. Back then, the app drawer was actually a drawer. Besides acting as a button, the gray tab could be pulled up the screen and would follow your finger, just like how the notification panel can be pulled down. There were additional apps like Alarm Clock, Calculator, Music, Pictures, Messaging, and Camera.

|

||||

|

||||

This was the first build with a fully customizable home screen. Long pressing on an app or widget allowed you to drag it around. You could drag an app out of the app drawer and make a home screen shortcut or long press on an existing home screen shortcut to move it.

|

||||

|

||||

0.9 is a reminder that Google was not the design powerhouse it is today. In fact, some of the design work for Android was farmed out to other companies at the time. You can see one sign of this in the clock widget, which contains the text “MALMO," the home town of design firm [The Astonishing Tribe][2].

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

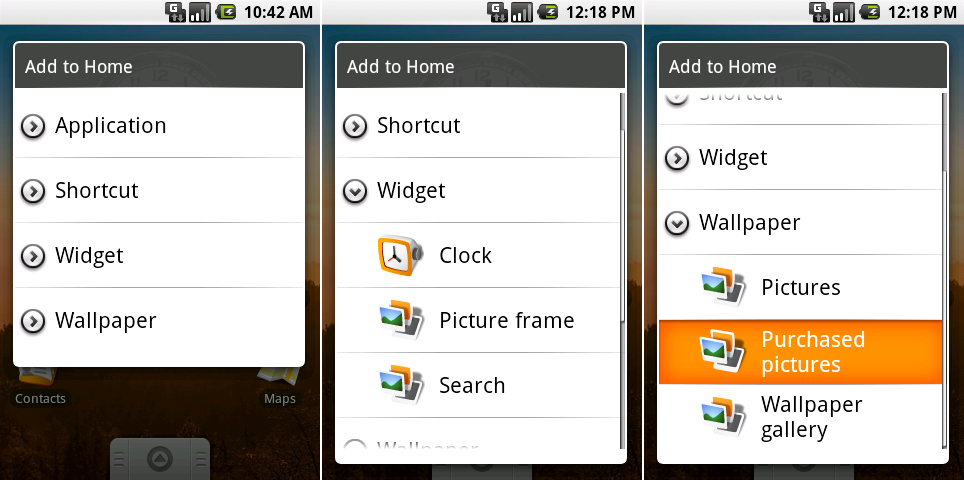

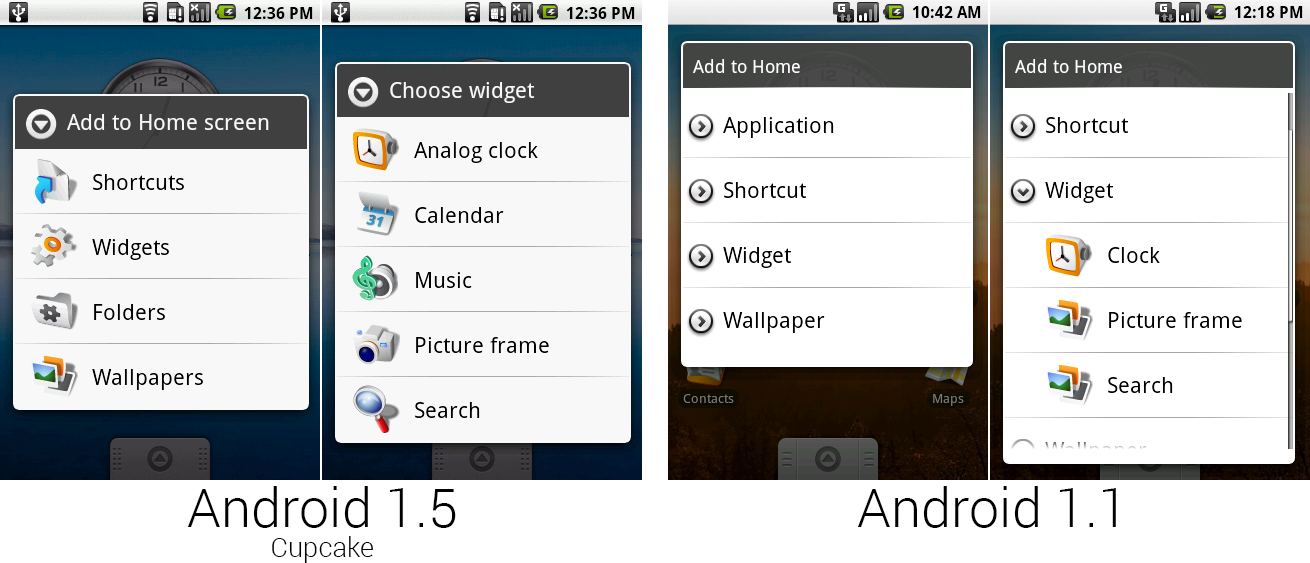

The “Add to Home" dialog in Android 0.9.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

There were only three widgets: Clock, Picture frame, and Search. The Search widget didn't even have a proper icon in the list—it used the Picture icon. Perhaps the most interesting item here was a "Purchased pictures" option in the wallpaper choices—a leftover from the days when purchasing ringtones on a dumbphone was a common occurrence. Google was either planning on selling wallpapers, or it was already adding a carrier at some point. The company never went through with the plan.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

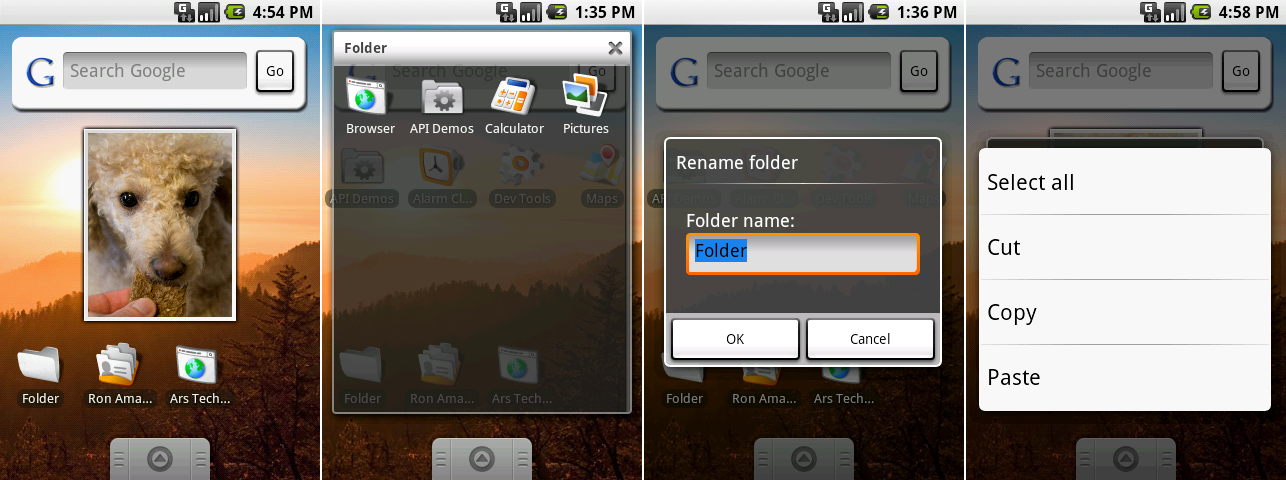

A collection of widgets, an open folder, renaming a folder, and the copy/paste menu.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

The left screen, above, shows the widgets for Google Search and pictures. Search didn't do anything other than give you a box to type in—there was no auto complete or additional UI. Typing in the box and hitting "Go" would launch the browser. The bottom row of icons revealed a few options for "shortcuts" from the long press menu, which created icons that opened an app to a certain screen. Individual contacts, browser bookmarks, and music playlists were all shortcuts that could all be added to the home screen in 0.9.

|

||||

|

||||

"Folders" was an option under the shortcuts heading despite not being a shortcut to anything. Once a blank folder was created, icons could be dragged into it and rearranged. Unlike today, there was no indication of what was in a folder; it was always a plain, white, empty-looking icon.

|

||||

|

||||

0.9 was also the first Android version to have OS-level copy/paste support. Long pressing on any text box would bring up a dialog allowing you to save or recall text from the clipboard. iOS didn't support copy/paste until almost two years later, so for a while, this was one of Android's big differentiators—and the source of many Internet arguments.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

From left to right: Android 0.9’s new menu, recent apps, power options, and lock screen.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

Android 0.9 was really starting to show its maturity. The home screen had a full set of menu items, including a settings option (although it didn't work yet) and a search button (because Google likes it when you search). The menu design was already in the final form that would last until Android 2.3 swapped it to black.

|

||||

|

||||

Long pressing on the hardware home button brought up a 3x2 grid of recent apps, a design that would stick around until the release of Android 3.0. Recent Apps blurred the exposed background, but that was strangely applied here and not on other popups like the "Add to home" dialog or the home screen folder view. The power menu was at least included in the blurry background club, and it was redesigned with icons and more commonly accepted names for functions. The power menu icons lacked padding, though, appearing cramped and awkward.

|

||||

|

||||

Android 0.9 featured a lock screen, albeit a very basic one. The black and gray lock screen had no on-screen method of unlocking—you needed to hit the hardware menu button.

|

||||

|

||||

----------

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

[Ron Amadeo][a] / Ron is the Reviews Editor at Ars Technica, where he specializes in Android OS and Google products. He is always on the hunt for a new gadget and loves to rip things apart to see how they work.

|

||||

|

||||

[@RonAmadeo][t]

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/3/

|

||||

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID) 校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创翻译,[Linux中国](http://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[1]:http://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2008/08/robotripping-hands-on-with-the-android-sdk-beta/

|

||||

[2]:http://www.tat.se/

|

||||

[a]:http://arstechnica.com/author/ronamadeo

|

||||

[t]:https://twitter.com/RonAmadeo

|

||||

@ -0,0 +1,75 @@

|

||||

The history of Android

|

||||

================================================================================

|

||||

|

||||

Android 0.9 showing off a horizontal home screen—a feature that wouldn’t make it to later versions.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

While it's hard to separate emulator and OS functionality, Android 0.9 was the first version to show off horizontal support. Surprisingly, almost everything supported horizontal mode, and 0.9 even outperforms KitKat in some respects. In KitKat, the home screen and dialer are locked to portrait mode and cannot rotate. Here, though, horizontal support wasn't a problem for either app. (Anyone know how to upgrade a Nexus 5 from KitKat to 0.9?)

|

||||

|

||||

This screenshot also shows off the new volume design used in 0.9. It dumped the old bell-style control that debuted in Milestone 3. It was a massive, screen-filling interface. Eventually, the redesign in Android 4.0 made it a bit smaller, but it remained an issue. (It's extremely annoying to not be able to see a video just because you want to bump up the volume.)

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The new notification panel, which ditched the application shortcut and added a top section.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

In just about every Android version, the notification panel gets tweaked, and 0.9 was no exception. The battery indicator was redrawn and changed to a darker shade of green, and the other status bar icons switched to black, white, and gray. The left area of the status bar was brilliantly repurposed to show the date when the panel was open.

|

||||

|

||||

A new top section was added to the notification panel that would display the carrier name ("Android" in the case of the emulator) and a huge button labeled "Clear notifications," which allowed you to finally remove a notification without having to open it. The application button was canned and replaced with the time the notification arrived, and the "latest events" text was swapped out for a simpler "notifications." The empty parts of the panel were now gray instead of white, and the bottom gripper was redesigned. The pictures seem misaligned on the bottom, but that was because Milestone 5's notification panel had white space around the bottom of the panel. Android 0.9 goes all the way to the edge.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

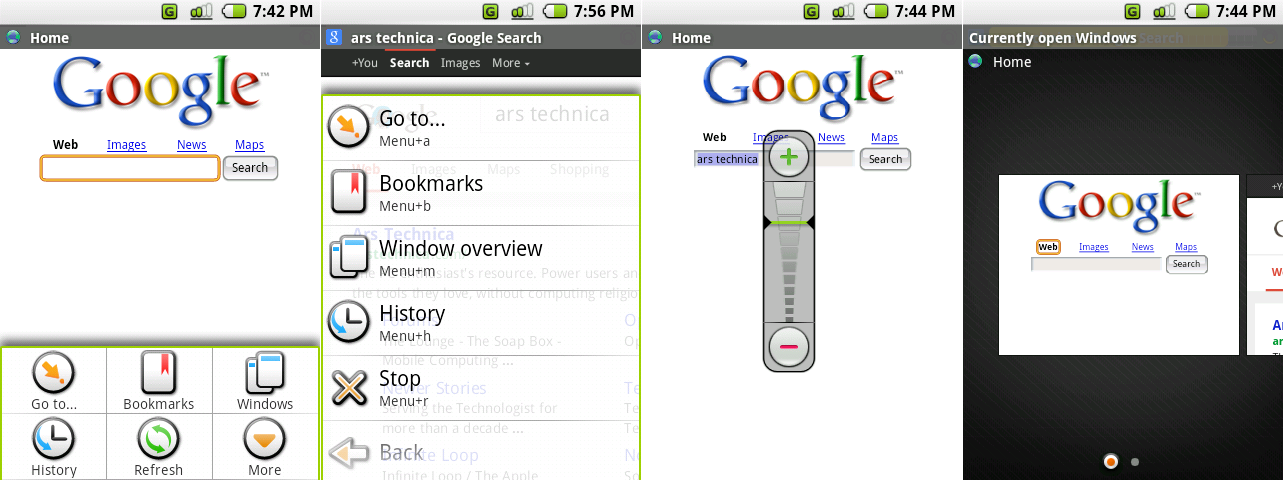

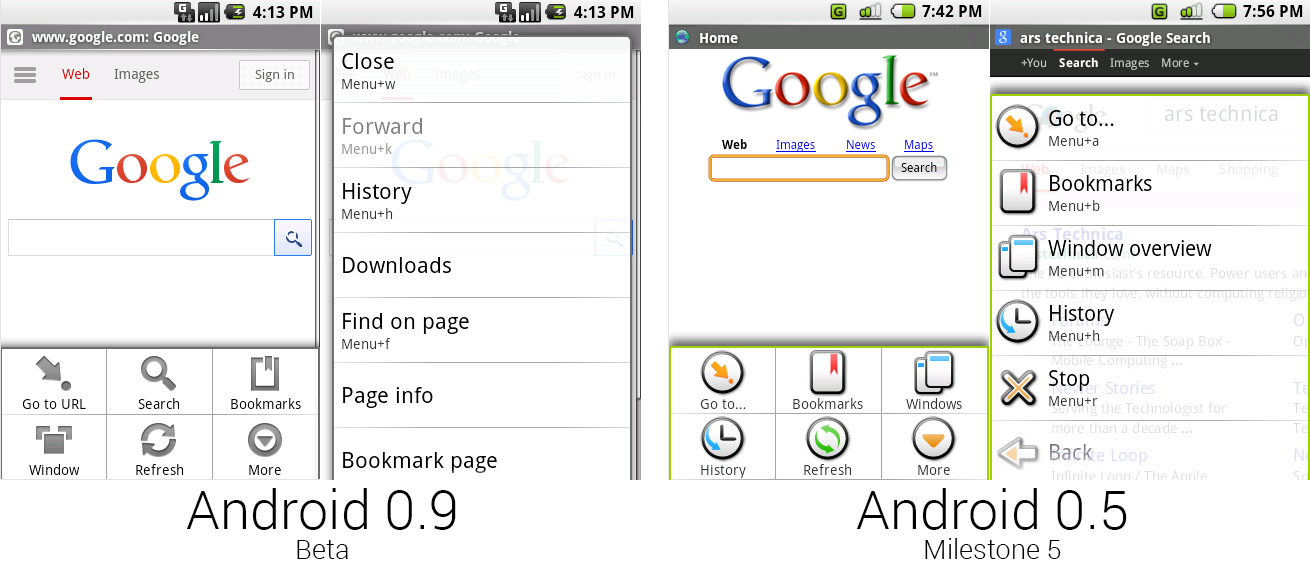

The browsers of 0.9 and 0.5, showing the new, colorless menus.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

The browser now loaded an actual website for the home page instead of the locally stored faux-Google of Milestone 5. The WebKit version rose up to 525.10, but it didn't seem to render the modern Google.com search button correctly. All throughout Android 0.9, the menu art from Milestone 5 was trashed and redrawn as gray icons. The difference between these screens is pretty significant, as all the color has been sucked out.

|

||||

|

||||

The "more" list-style menu grew a little taller, and it was now just a plain list with no icons. Android 0.9 gained yet another search method, this time in the browser menu. Along with the home screen widget, home screen menu button, and browser homepage, that made four search boxes. Google never hid what its prime business was, even in its OS.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

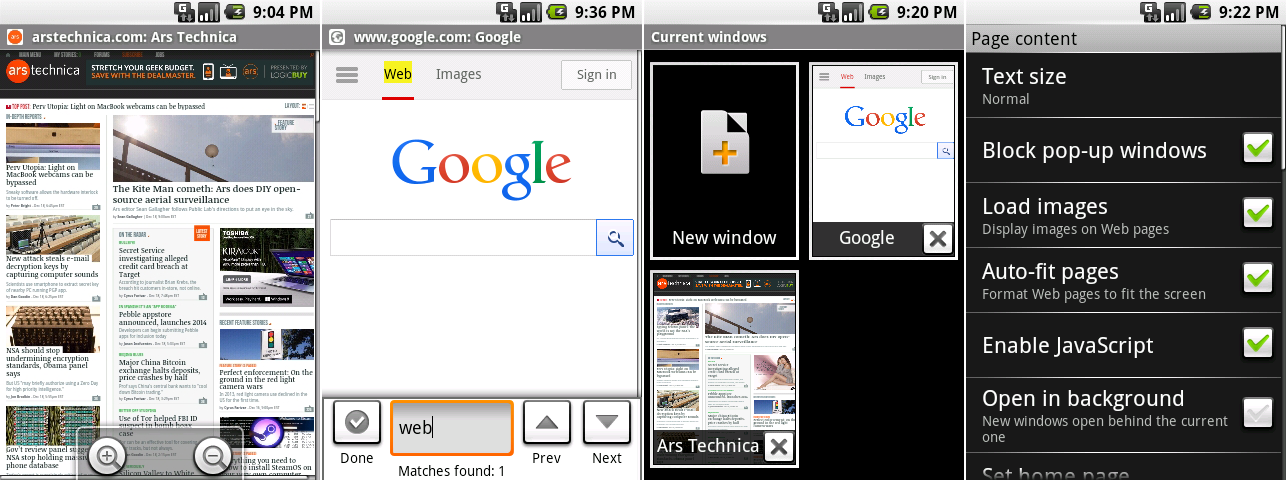

From left to right: Android 0.9’s browser showing off the zoom controls, find-in-page interface, browser windows, and the settings.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

Android 0.9 brought tons of browser improvements. The zoom controls were thankfully reworked from the crazy vertical controls to simpler plus and minus buttons. Google made the common-sense decision of moving the controls from the center of the screen to the bottom. In these zoom controls, the Android struggle with consistency became apparent. These appeared to be the only round buttons in the OS.

|

||||

|

||||

0.9's new "find in page" feature could highlight words in the page. But overall, the UI was still very rough—the text box was much taller than it should be, and the "done" button with a checkbox was a one-of-a-kind icon for this screen. "Done" was basically a "close" button, which means it should probably have been a right-aligned "X" button.

|

||||

|

||||

The main OS didn't have a settings screen in this build, but the browser finally had its own settings screen. It featured desktop-style options for pop ups, javascript, privacy and cookies, saved passwords and form data. There was even Google Gears integration (remember [Google Gears?][1]).

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

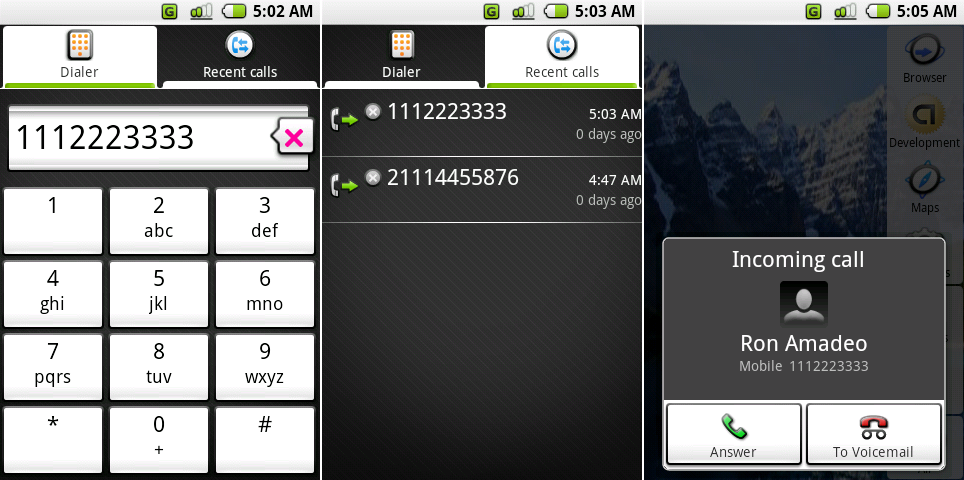

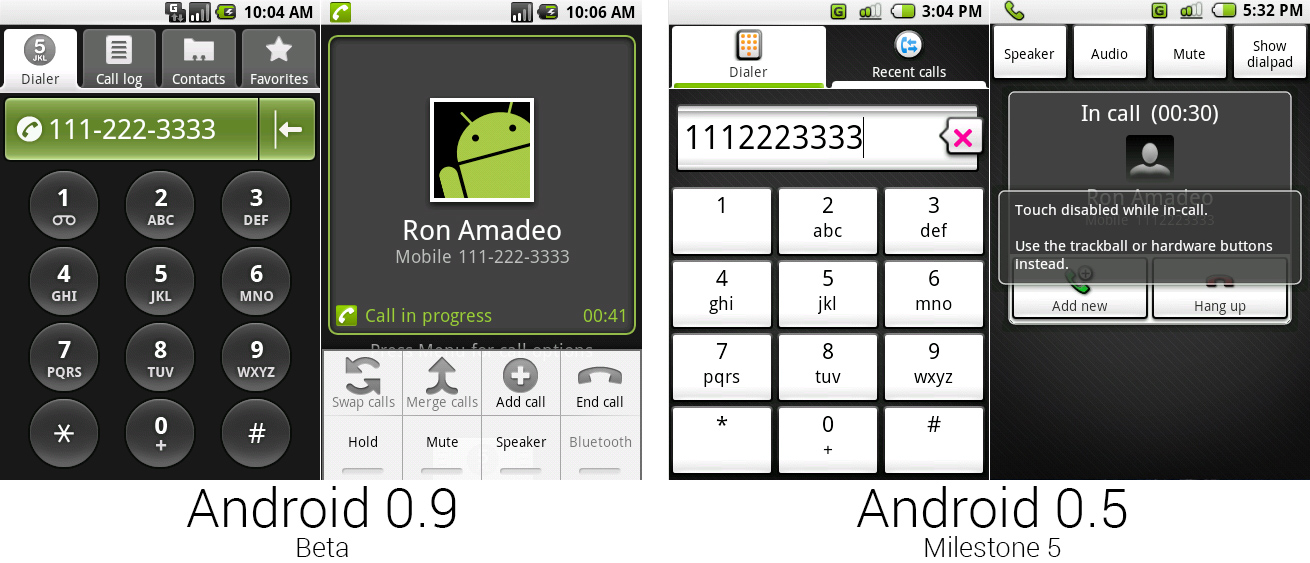

The dialer and in-progress call screen with the menu open.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

Dialer and Contacts in Android 0.9 were actually the same app—the two icons just opened different tabs. Attaching contacts to the dialer like this suggested the primary purpose of a smartphone contact was still for calls, not to text, e-mail, IM, or look up an address. Eventually Google would fully embrace alternative smartphone communications and split up contacts and dialer into separate apps.

|

||||

|

||||

Most of the dialer weirdness in Milestone 5 was wiped out in Android 0.9. The "minimizing" tabs were replaced with a normal set of dark/light tabs. The speech bubble backspace button was changed to a normal backspace icon and integrated into the number display. The number buttons were changed to circles despite everything else in the OS being a rounded rectangle (at least the text was vertically aligned this time). The company also fixed the unbalanced "one," "star," and "pound" keys from Milestone 5.

|

||||

|

||||

Tapping on the number display in Android 0.9 would start a call. This was important, as it was a big step in getting rid of the hardware "Call" and "End" keys on Android devices. The incoming call screen, on the other hand, went in the complete opposite direction and removed the on-screen “Answer" and “Decline" buttons present in Android 0.5. Google would spend the next few versions fumbling around between needing and not needing hardware call buttons on certain screens. With Android 2.0 and the Motorola Droid, though, call buttons were finally made optional.

|

||||

|

||||

All of the options for the in-call screen were hidden under the menu button. Milestone 5 didn't support a proximity sensor, so it took the brute force route of disabling the touch screen during a call. 0.9 was developed for the G1, which had a proximity sensor. Finally, Google didn't have to kill the touch sensor during a call.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

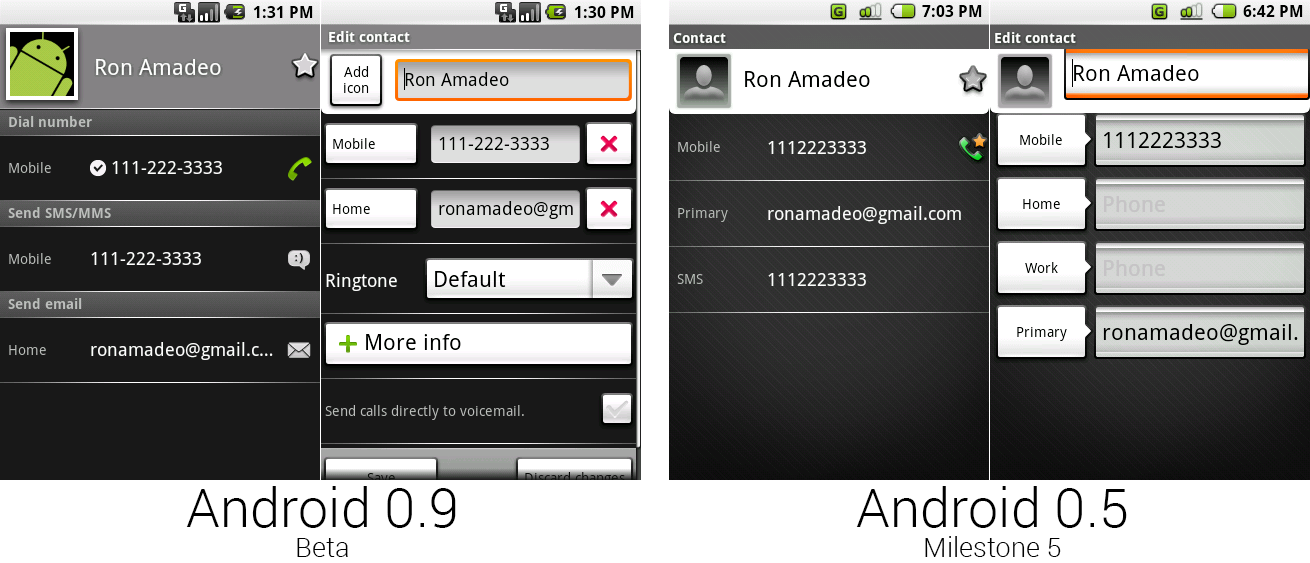

The individual contacts screen and edit contacts screen for Android 0.9 and 0.5.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

Milestone 5 had confusing labels for some contact information, like e-mail only being labeled "primary" instead of something like “primary e-mail." Android 0.9 corrected this with horizontal headers for each section. There were now action icons for each contact type on the left side, too.

|

||||

|

||||

The edit contact screen was now a much busier place. There were delete buttons for every field, per-contact ringtones, an on-screen "more info" button for adding fields, a checkbox to send calls directly to voicemail, and "Save and "discard changes" buttons at the bottom of the list. Functionally, it was a big improvement over the old version, but it still looked very messy.

|

||||

|

||||

----------

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

[Ron Amadeo][a] / Ron is the Reviews Editor at Ars Technica, where he specializes in Android OS and Google products. He is always on the hunt for a new gadget and loves to rip things apart to see how they work.

|

||||

|

||||

[@RonAmadeo][t]

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/4/

|

||||

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID) 校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创翻译,[Linux中国](http://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[1]:http://www.tat.se/

|

||||

[a]:http://arstechnica.com/author/ronamadeo

|

||||

[t]:https://twitter.com/RonAmadeo

|

||||

@ -0,0 +1,88 @@

|

||||

The history of Android

|

||||

================================================================================

|

||||

|

||||

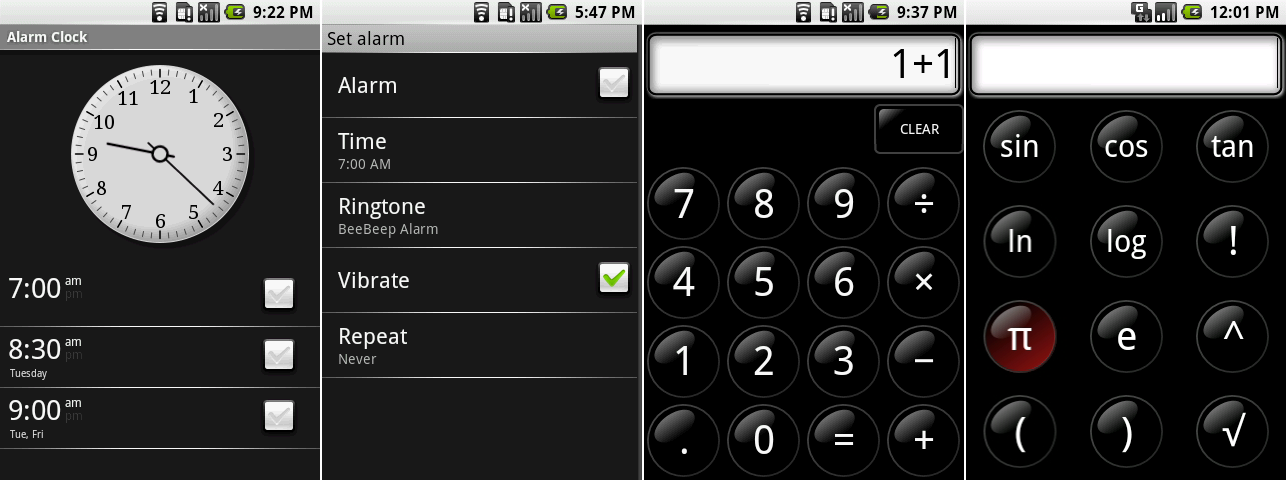

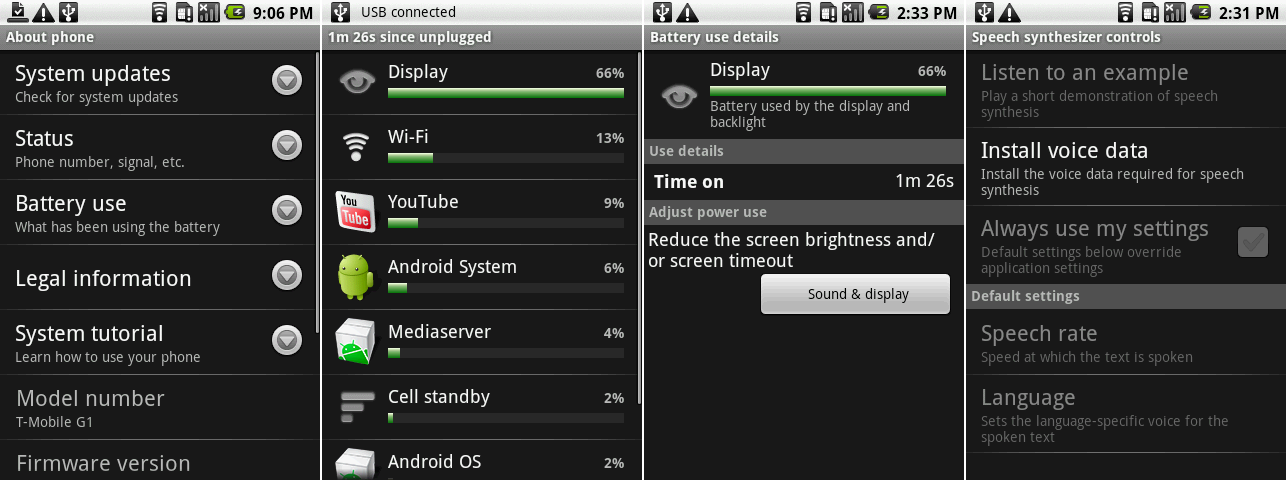

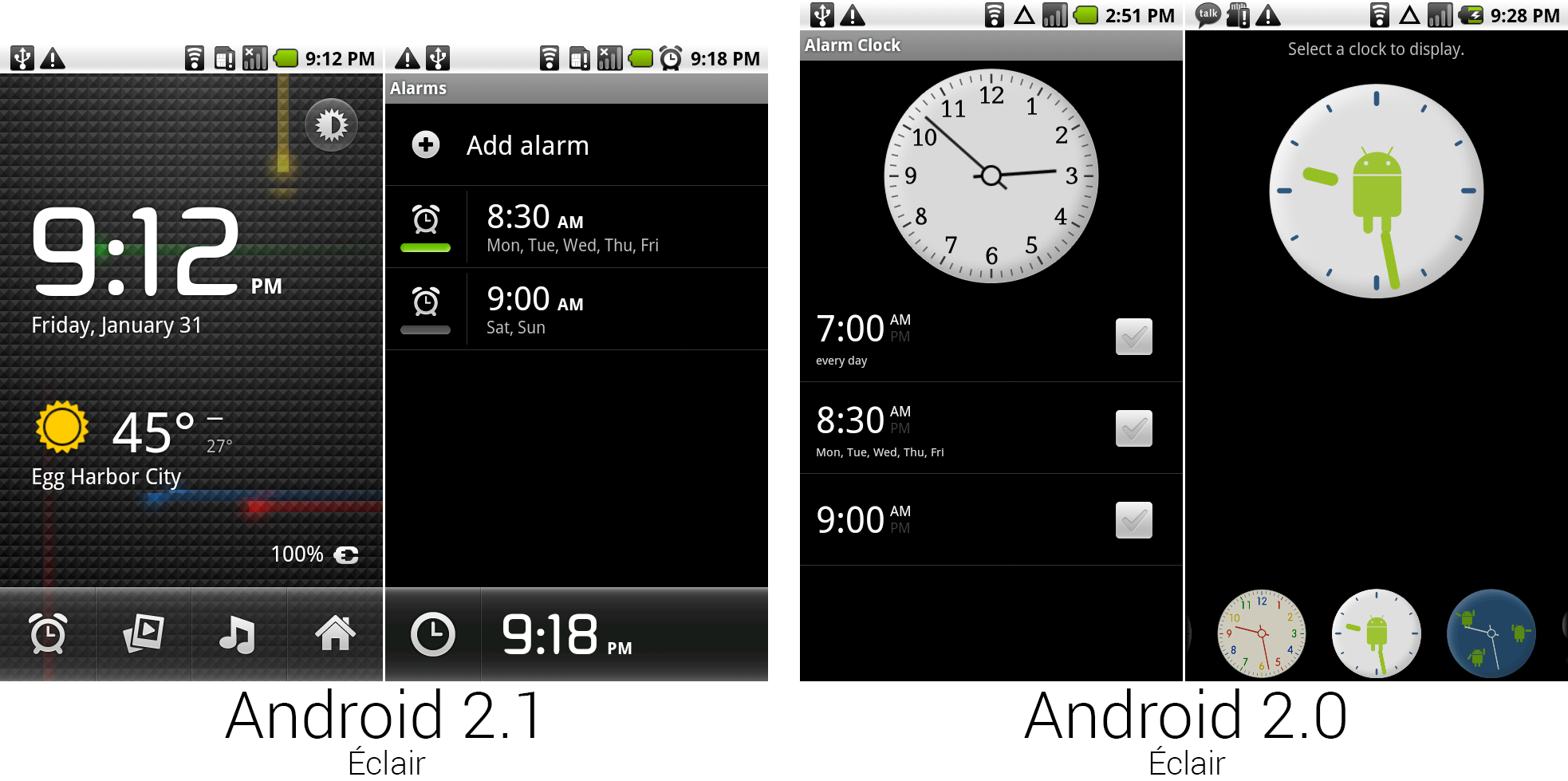

The main alarm screen, setting an alarm, the calculator, and the calculator advanced functions screen.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

Android 0.9 gave us the first look at the Alarm and Calculator apps. The alarm app featured a plain analog clock with a scrolling list of alarms on the bottom. Rather than some kind of on/off switch, alarms were set with a checkbox. Alarms could be set to repeat at certain days of the week, and there was a whole list of selectable, unique alarm sounds.

|

||||

|

||||

The calculator was an all-black app with glossy, round buttons. Through the menu, it was possible to bring up an additional panel with advanced functions. Again consistency was not Google’s strong suit. The on-press highlight on the pi key was red—in the rest of Android 0.9, the on-press highlight was usually orange. In fact, everything used in the calculator was 100 percent custom artwork limited to only the calculator.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

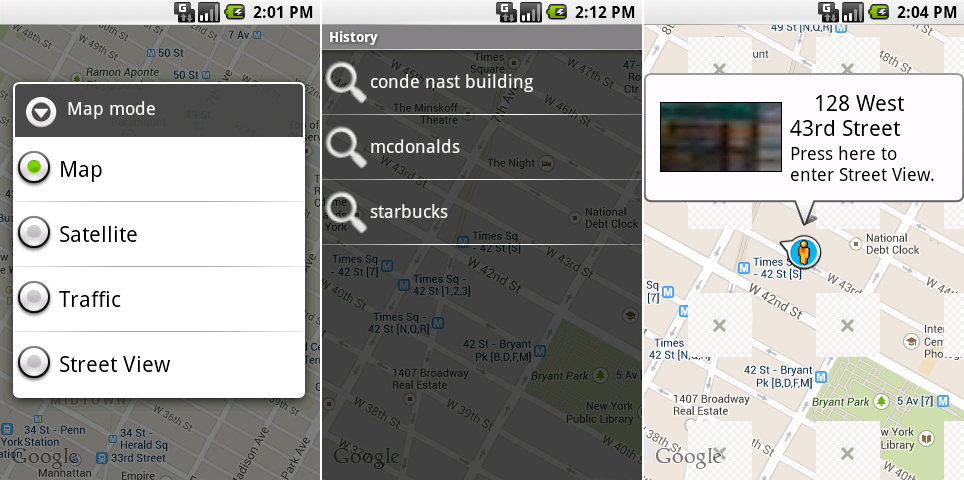

Google Maps with the menu open and the new directions interface.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

Google Maps actually worked in Android 0.9—the client could connect to the Google Maps server and pull down tiles. (For our images, remember that Google Maps is cloud based. Even the oldest of clients will still pull down modern map tiles, so ignore the actual map tiles pictured.) The Maps menu got the same all-gray treatment as the browser menu, and the zoom controls were the same as the browser too. The all-important "My Location" button finally arrived, meaning this version of Maps supported GPS location.

|

||||

|

||||

The directions interface was revamped. The weird speech bubbles with misaligned plus buttons were swapped out for a more communicative bookmark icon, the swap field button moved to the left, and the go button was now labeled "Route."

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

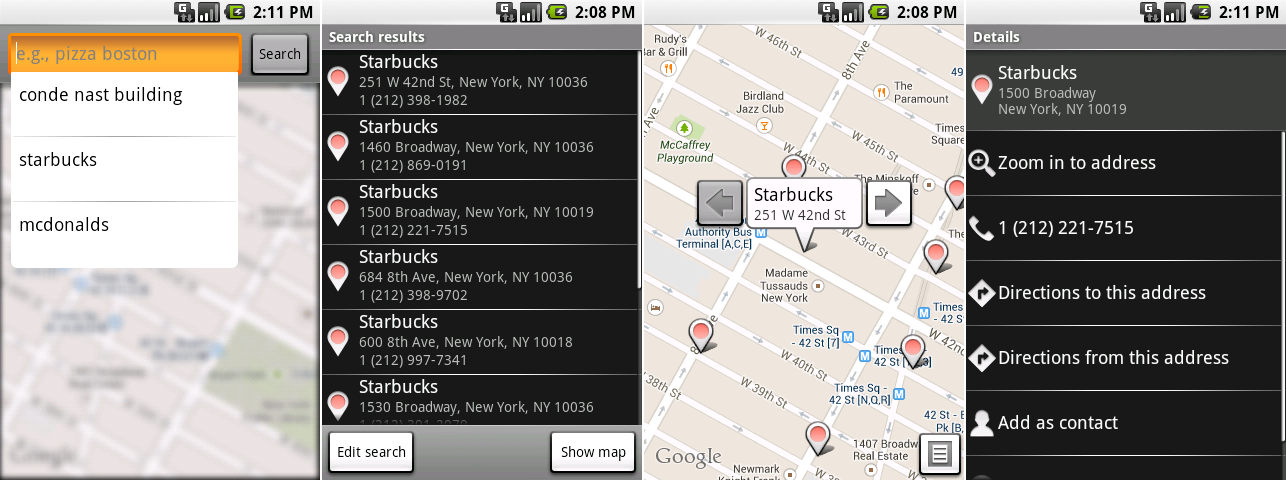

The Google Maps layers selector, search history, and the now-broken street view mode.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

"Layers" was renamed "Map Mode" and switched to a radio button list. Only one map type was available at a time—you couldn't see traffic on the satellite view, for instance. Buried in the menu was a hastily thrown together search history screen. History seemed like only a proof-of-concept, with giant, blurry search icons that rammed up against search terms on a transparent background.

|

||||

|

||||

Street View used to be a separate app (although it was never made available to the public), but in 0.9 it was integrated into Google Maps as a Map Mode. You could drag the little pegman around, and it would display a popup bubble showing the thumbnail for Street View. Tapping on the thumbnail would launch Street View for that area. At the time, Street View showed nothing other than a scrollable 360 degree image—there was no UI on the interface at all.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Our first look at the Google Maps search interface. These shots show the search bar, the results in a list, the results in a map, and a business page.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

Android 0.9 also gave us our first look at the texting app, called "Messaging." Like many early Android designs, Messaging wasn't sure if it should be a dark app or a light app. The first visible screen was the message list, a stark black void of nothingness that looked like it was built on top of the settings interface. After tapping on “New Message" or one of the existing conversations, though, you were taken to a white and blue scrolling list of text messages. The two connected screens couldn’t be more different.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

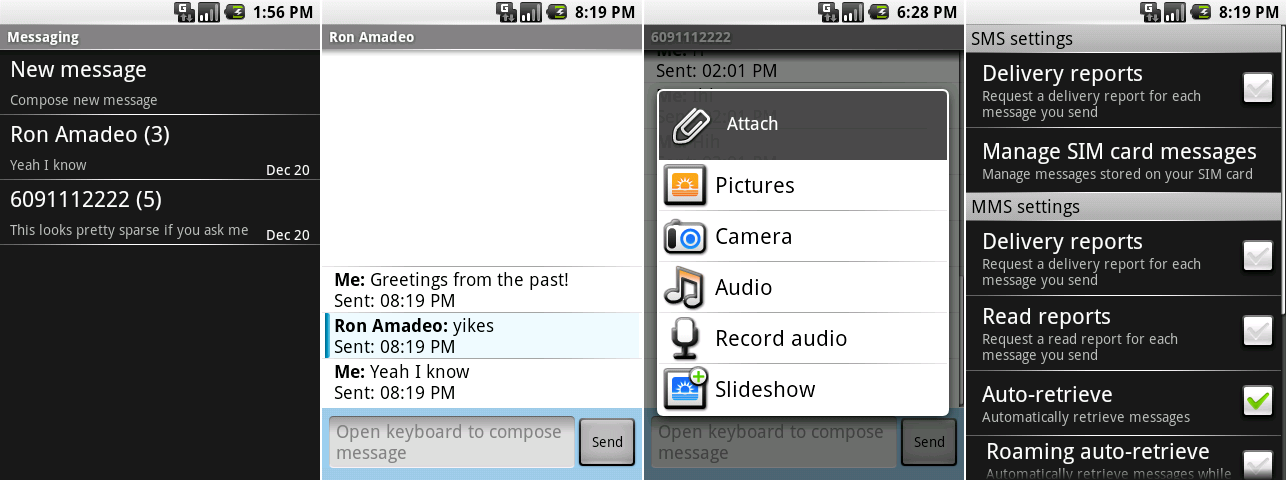

The SMS app’s chat window, attachment screen, chat list, and setting.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

Messaging supported a range of attachments: you could tack on pictures, audio, or a slideshow to your message. Pictures and audio could be recorded on the fly or pulled from phone storage. Another odd UI choice was that Android already had an established icon for almost everything in the attach menu, but Messaging used all-custom art instead.

|

||||

|

||||

Messaging was one of the first apps to have its own settings screen. Users could request read and delivery reports and set download preferences.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

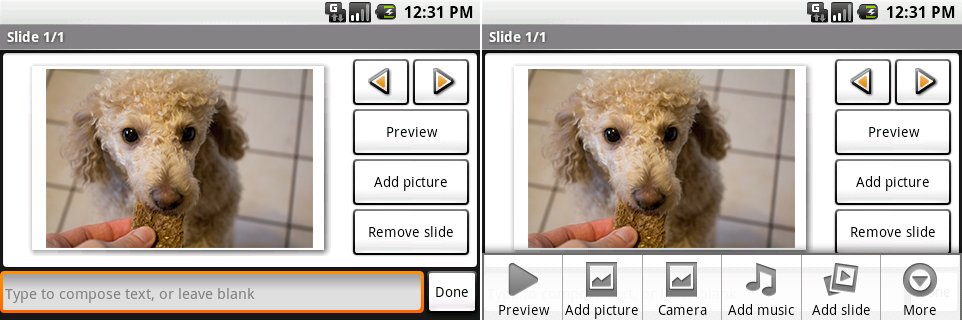

The slideshow creator. The right picture shows the menu options.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

The "slideshow" option in attachments would actually launch a fully featured slideshow creator. You could add pictures, choose the slide order, add music, change the duration of each slide, and add text. This was complicated enough to have its own app icon, but amazingly it was buried in the menu of the SMS app. This was one of the few Android apps that was completely unusable in portrait mode—the only way to see the picture and the controls was in landscape. Strangely, it would still rotate to portrait, but the layout just became a train wreck.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

The Music player’s main navigation page, song list, album list, and “now playing" screen.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

Android 0.9 was the first to bring a music app to Android. The primary screen was mostly just four big, chunky navigation buttons that would take you to each music view. At the bottom of the app was a "now playing" bar that only contained the track name, artist, and a play/pause button. The song list had only a bare minimum interface, only showing the song name, artist, album and runtime. Album art was the only hope of seeing any color in this app. It was displayed as a tiny thumbnail in the album view and as a big, quarter-screen image in the Now Playing view.

|

||||

|

||||

Like most parts of Android in this era, the interface may not have been much to look at, but the features were there. The Now Playing screen had a button for a playlist queue that allowed you to drag songs around, shuffle, repeat, search, and choose background audio.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

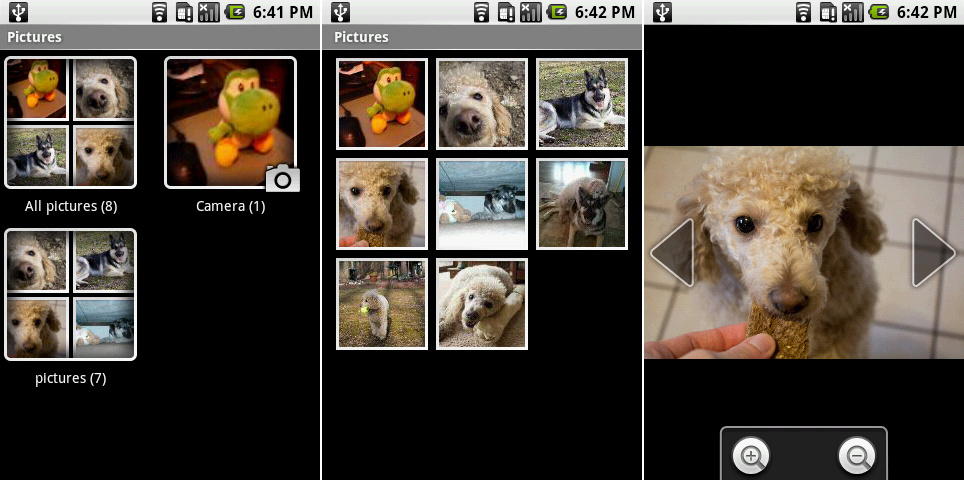

The “Pictures" all album view, individual album view, and a single picture view.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

The photo gallery was simply called "Pictures." The initial view showed all your albums. The two default ones were "Camera" and a large unified album called "All pictures." The thumbnail for each album was made up of a 2x2 grid of pictures, and every picture got a thick, white frame.

|

||||

|

||||

The individual album view was about what you would expect: a scrolling grid of pictures. You couldn't swipe through individual pictures—large left and right arrows flanking the individual picture had to be tapped on to move through an album. There was no pinch-zoom either; you had to zoom in and out with buttons.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

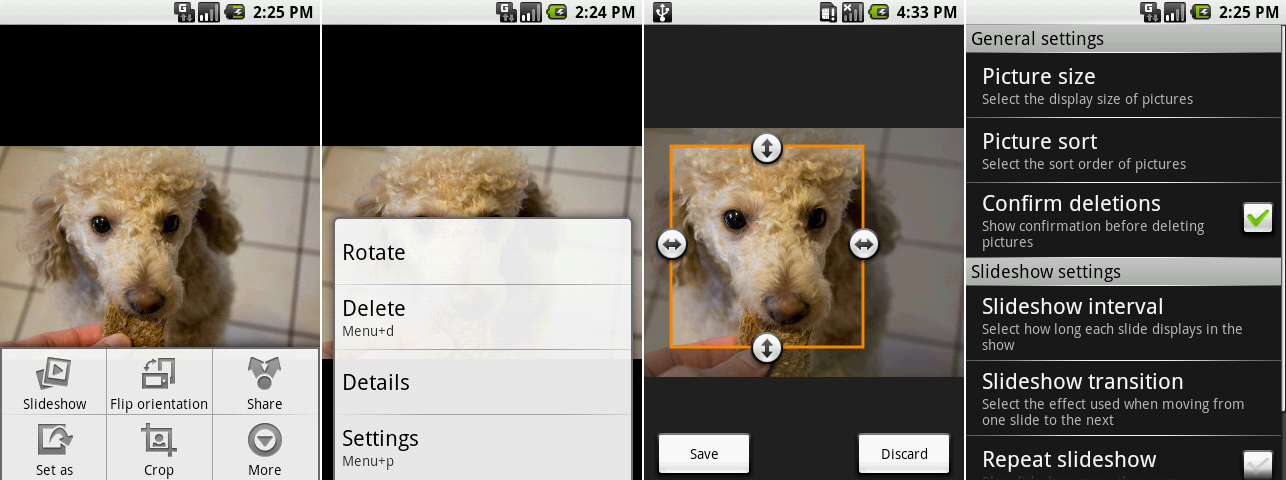

Picture editing! These screenshots show an open menu, the “more" menu, cropping, and the settings.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

"Pictures" looked simple until you hit the menu button and suddenly accessed a myriad of options. Pictures could be cropped, rotated, deleted, or set as a wallpaper or contact icon. Like the browser, all of this was accomplished through a clumsy double-menu system. But again, why do two related menus look completely different?

|

||||

|

||||

Android 0.9 came out a mere two months before the first commercial release of Android. That was just enough time for app developers to make sure their apps worked—and for Google to do some testing and bug squashing before the big release.

|

||||

|

||||

----------

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

[Ron Amadeo][a] / Ron is the Reviews Editor at Ars Technica, where he specializes in Android OS and Google products. He is always on the hunt for a new gadget and loves to rip things apart to see how they work.

|

||||

|

||||

[@RonAmadeo][t]

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/5/

|

||||

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID) 校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创翻译,[Linux中国](http://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:http://arstechnica.com/author/ronamadeo

|

||||

[t]:https://twitter.com/RonAmadeo

|

||||

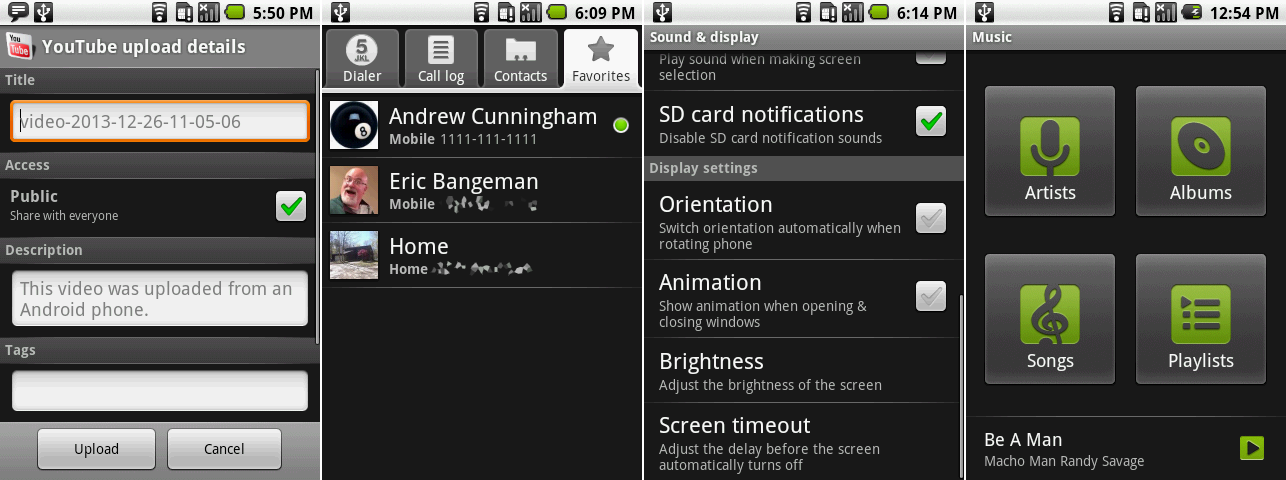

@ -0,0 +1,73 @@

|

||||

The history of Android

|

||||

================================================================================

|

||||

|

||||

The T-Mobile G1

|

||||

Photo by T-Mobile

|

||||

|

||||

### Android 1.0—introducing Google Apps and actual hardware ###

|

||||

|

||||

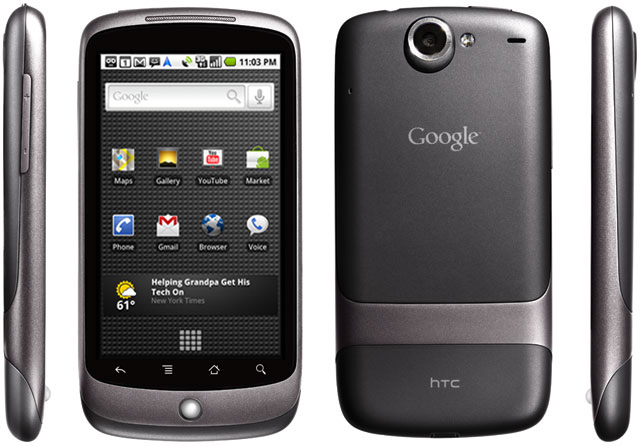

By October 2008, Android 1.0 was ready for launch, and the OS debuted on the [T-Mobile G1][1] (AKA the HTC Dream). The G1 was released into a market dominated by the iPhone 3G and the [Nokia 1680 classic][2]. (Both of those phones went on to tie for the [best selling phone][3] of 2008, selling 35 million units each.) Hard numbers of G1 sales are tough to come by, but T-Mobile announced the device broke the one million units sold barrier in April 2009. It was way behind the competition by any measure.

|

||||

|

||||

The G1 was packing a single-core 528Mhz ARM 11 processor, an Adreno 130 GPU, 192MB of RAM, and a whopping 256MB of storage for the OS and Apps. It had a 3.2-inch, 320x480 display, which was mounted to a sliding mechanism that revealed a full hardware keyboard. So while Android software has certainly come a long way, the hardware has, too. Today, we can get much better specs than this in a watch form factor: the latest [Samsung smart watch][4] has 512MB of RAM and a 1GHz dual-core processor.

|

||||

|

||||

While the iPhone had a minimal amount of buttons, the G1 was the complete opposite, sporting almost every hardware control that was ever invented. It had call and end call buttons, home, back, and menu buttons, a shutter button for the camera, a volume rocker, a trackball, and, of course, about 50 keyboard buttons. Future Android devices would slowly back away from thousand-button interfaces, with nearly every new flagship lessening the number of buttons.

|

||||

|

||||

But for the first time, people saw Android running on actual hardware instead of a frustratingly slow emulator. Android 1.0 didn't have the smoothness, flare, or press coverage of the iPhone. It wasn't as capable as Windows Mobile 6.5. Still, it was a good start.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

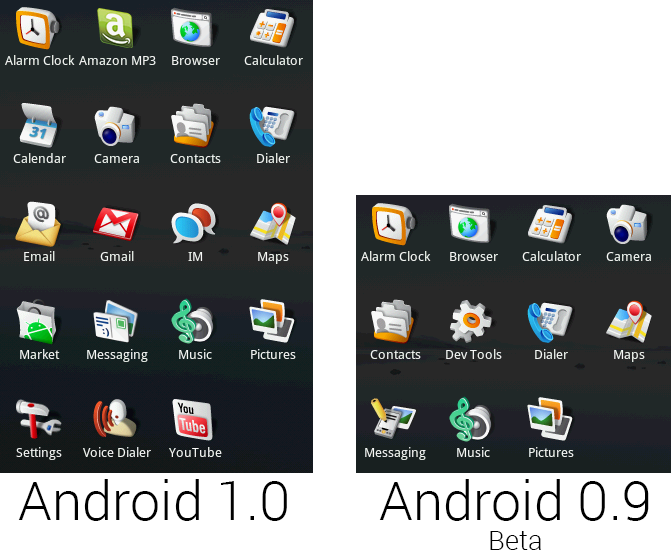

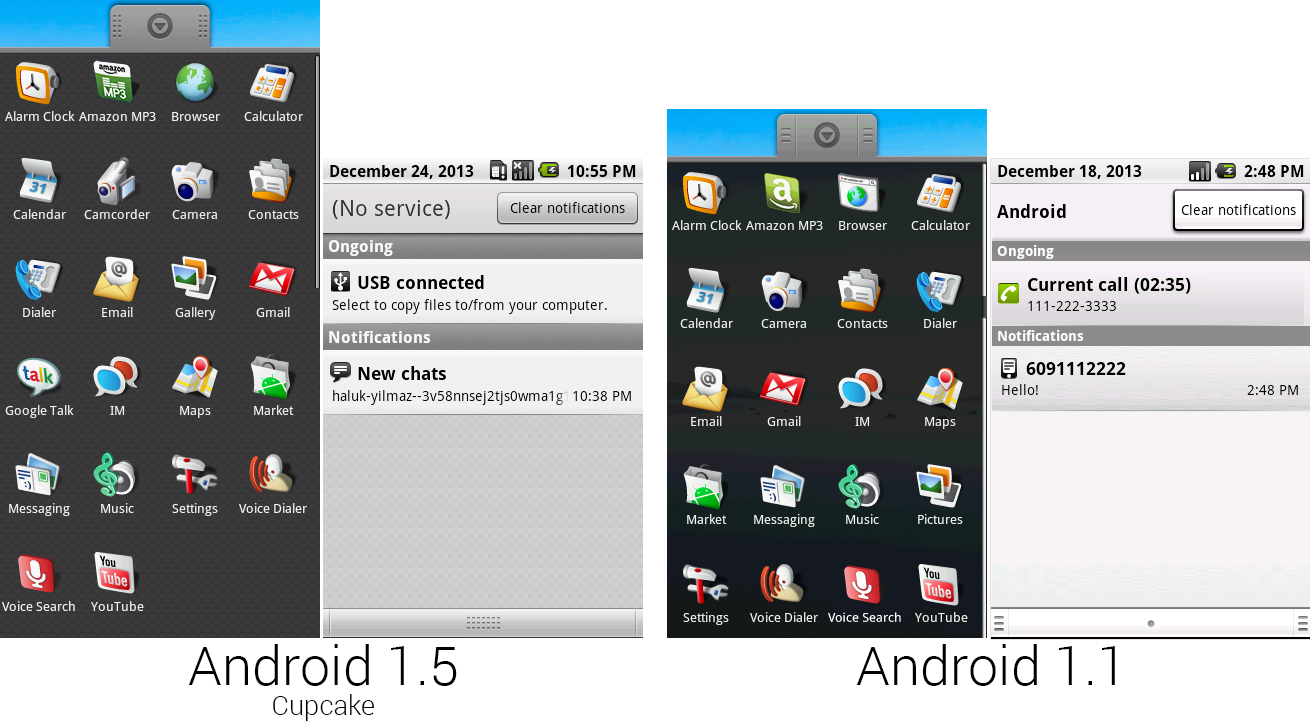

The default app selection of Android 1.0 and 0.9.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

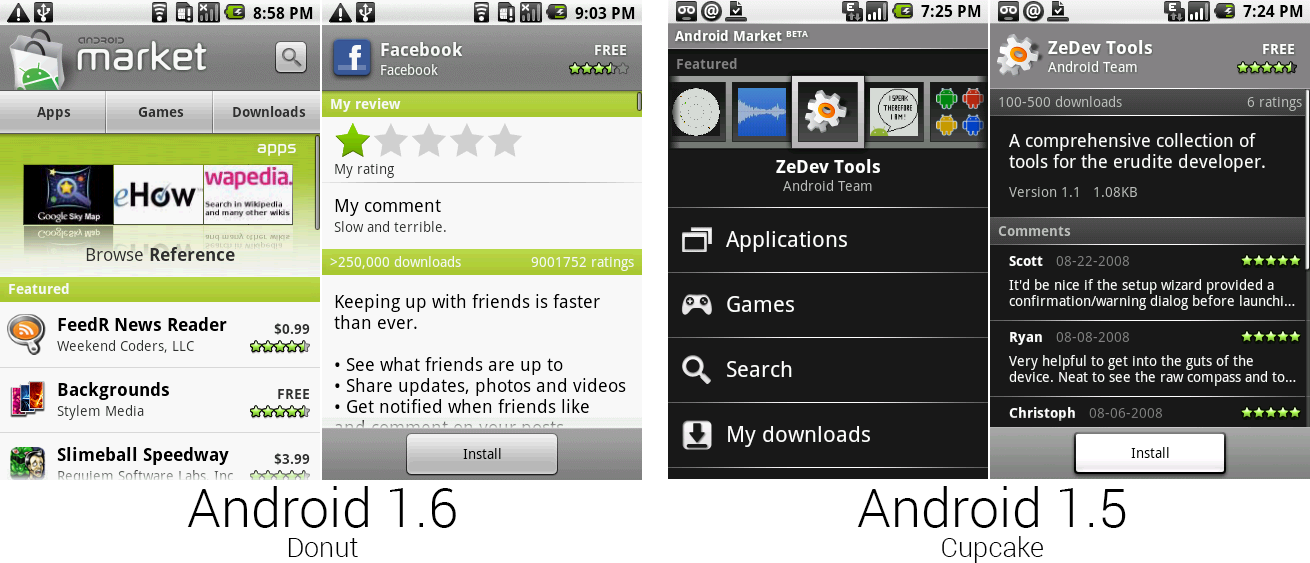

The core of Android 1.0 didn't look significantly different from the beta version released two months earlier, but the consumer product brought a ton more apps, including the full suite of Google apps. Calendar, Email, Gmail, IM, Market, Settings, Voice Dialer, and YouTube were all new. At the time, music was the dominant media type on smartphones, the king of which was the iTunes music store. Google didn't have an in-house music service of its own, so it tapped Amazon and bundled the Amazon MP3 store.

|

||||

|

||||

The most important addition to Android 1.0 was the debut of Google's store, called "Android Market Beta." While most companies were content with calling their app catalog some variant of "app store"—meaning a store that sold apps and only apps—Google had much wider ambitions. It went with the much more general name of "Android Market." The idea was that the Android Market would not just house apps, but everything you needed for your Android device.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

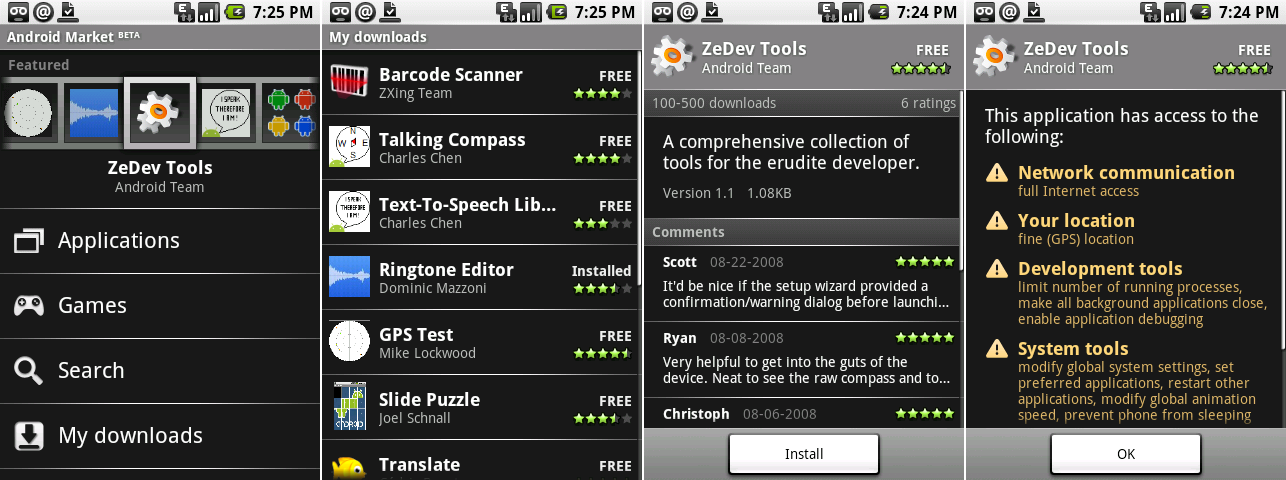

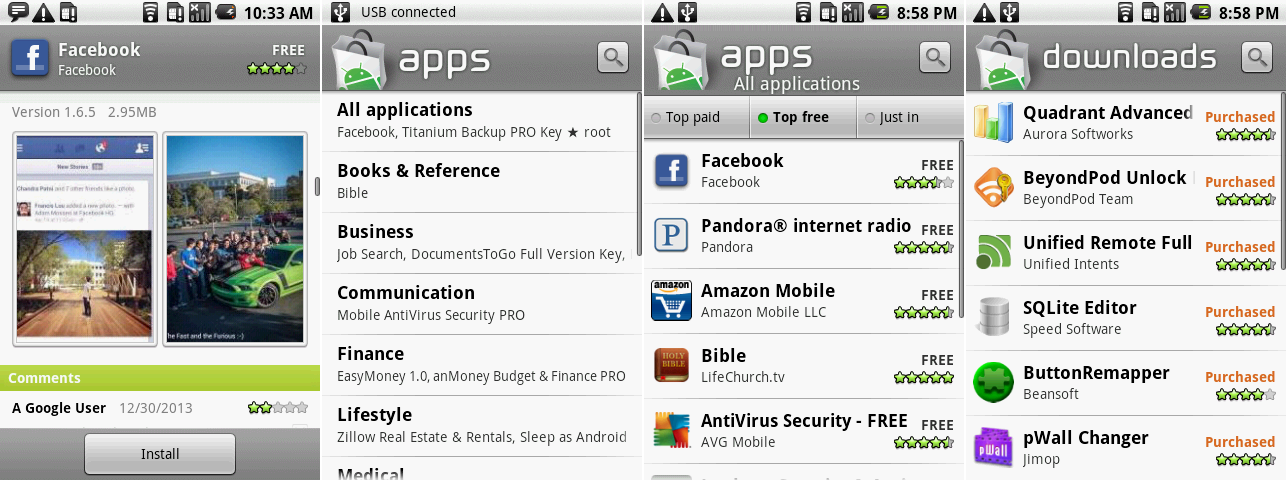

The first Android Market client. Screenshots show the main page, “my downloads," an app page, and an app permissions page.

|

||||

Photo by [Google][5]

|

||||

|

||||

At the time, the Android Market only offered apps and games, and developers weren't even able to charge for them. Apple's App Store had a four-month head start on the Android Market, but Google's big differentiator was that Android's store was almost completely open. On the iPhone, apps were subject to review by Apple and had to meet design and technical guidelines. Potential apps also weren't allowed to duplicate the stock functionality. On the Android Market, developers were free to do whatever they wanted, including replacing the stock apps. The lack of control would turn out to be a blessing and a curse. It allowed developers to innovate on the existing functionality, but it also meant even the trashiest applications were allowed in.

|

||||

|

||||

Today, this client is another app that can no longer communicate with Google's servers. Luckily, it's one of the few early Android apps [actually documented][6] on the Internet. The main screen provided links to the common areas like Apps, Games, Search, and Downloads, and the top section had horizontally scrolling icons for featured apps. Search results and the "My Downloads" page displayed apps in a scrolling list, showing the name, developers, cost (at this point, always free), and rating. Individual app pages showed a brief description, install count, comments and ratings from users, and the all-important install button. This early Android Market didn’t support pictures, and the only field for developers was a description box with a 500-character limit. This made things like maintaining a changelog very difficult, as the only spot to put it was in the description.

|

||||

|

||||

Right out of the gate, the Android Market showed permissions that an app required before installing. This is something Apple wouldn't get around to implementing until 2012, after an iOS app was caught [uploading entire address books][7] to the cloud without the user's knowledge. The permissions display gave a full rundown of what permissions an app was using, although this version railroaded users into agreeing. There was an “OK" button, but no way to cancel other than the back button.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

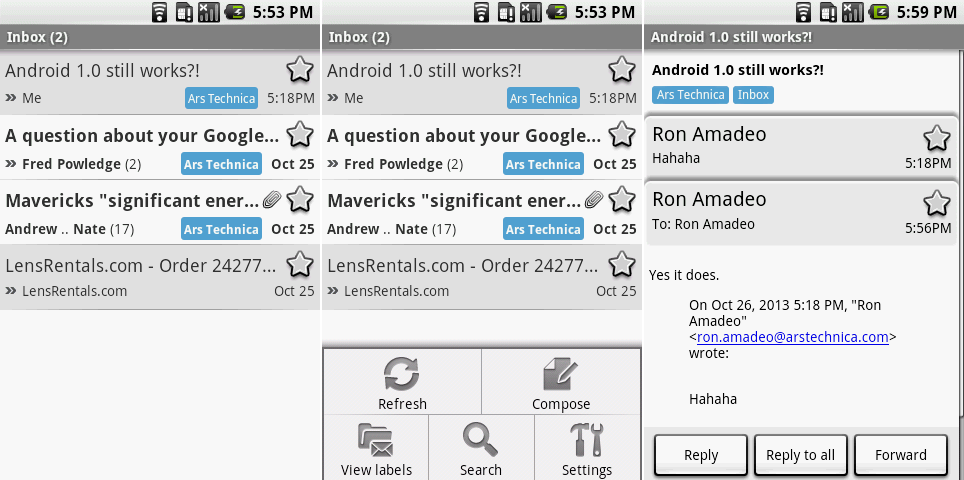

Gmail showing the inbox, the inbox with the menu open.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

The next most important app was probably Gmail. Most of the base functionality was here already. Unviewed messages showed up in bold, and labels displayed as colored tags. Individual messages in the Inbox showed the subject, author(s), and number of replies in a conversation. The trademark Gmail star was here—a quick tap would star or unstar something. As usual for early versions of Android, the Menu housed all the buttons on the main inbox view. Once inside a message, though, things got a little more modern, with "reply" and "forward" buttons as permanent fixtures at the bottom of the screen. Individual replies could be expanded and collapsed just by tapping on them.

|

||||

|

||||

The rounded corners, shadows, and bubbly icons gave the whole app a "cartoonish" look, but it was a good start. Android's function-first philosophy was really coming through here: Gmail supported labels, threaded messaging, searching, and push e-mail.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Gmail’s label view, compose screen, and settings on Android 1.0.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

But if you thought Gmail was ugly, the Email app took it to another level. There was no separate inbox or folder view—everything was mashed into a single screen. The app presented you with a list of folders and tapping on one would expand the contents in-line. Unread messages were denoted with a green line on the left, and that was about it for the e-mail interface. The app supported IMAP and POP3 but not Exchange.

|

||||

|

||||

----------

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

[Ron Amadeo][a] / Ron is the Reviews Editor at Ars Technica, where he specializes in Android OS and Google products. He is always on the hunt for a new gadget and loves to rip things apart to see how they work.

|

||||

|

||||

[@RonAmadeo][t]

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/06/building-android-a-40000-word-history-of-googles-mobile-os/6/

|

||||

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID) 校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创翻译,[Linux中国](http://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[1]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2008/10/android-g1-review/

|

||||

[2]:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nokia_1680_classic

|

||||

[3]:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_best-selling_mobile_phones#2008

|

||||

[4]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2014/04/review-we-wear-samsungs-galaxy-gear-and-galaxy-fit-so-you-dont-have-to/

|

||||

[5]:http://android-developers.blogspot.com/2008/08/android-market-user-driven-content.html

|

||||

[6]:http://android-developers.blogspot.com/2008/08/android-market-user-driven-content.html

|

||||

[7]:http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/2012/02/path-addresses-privacy-controversy-but-social-apps-remain-a-risk-to-users/

|

||||

[a]:http://arstechnica.com/author/ronamadeo

|

||||

[t]:https://twitter.com/RonAmadeo

|

||||

@ -0,0 +1,109 @@

|

||||

The history of Android

|

||||

================================================================================

|

||||

|

||||

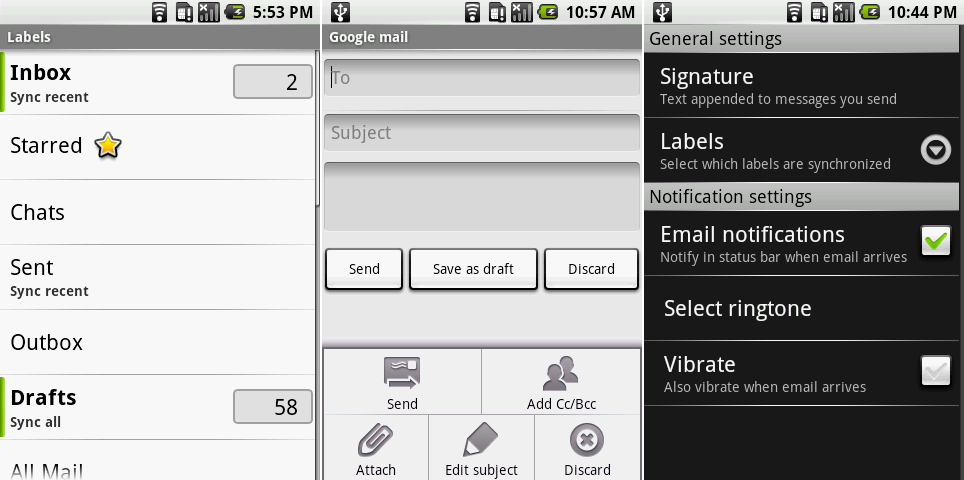

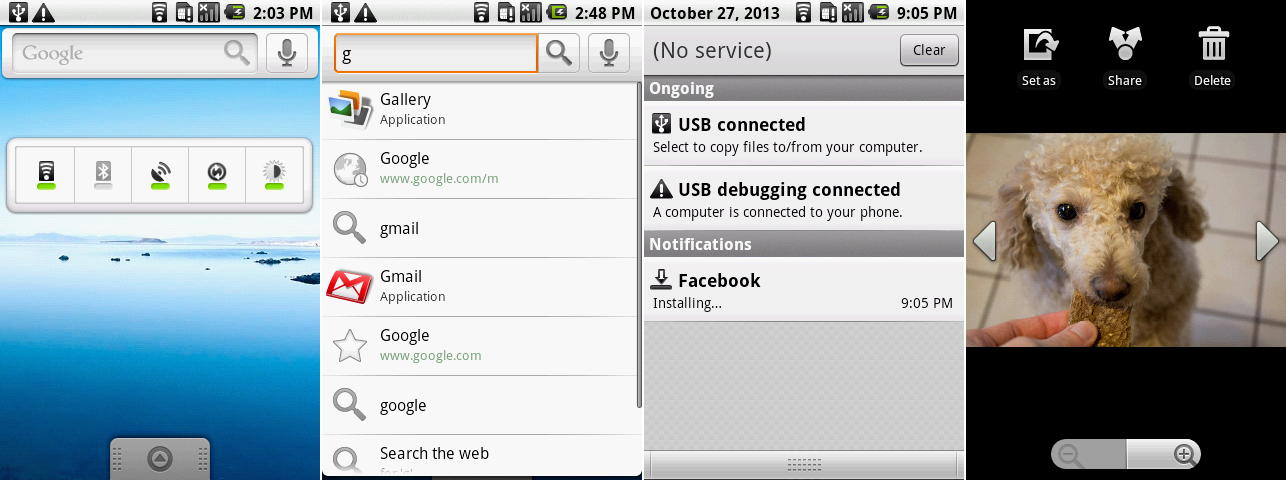

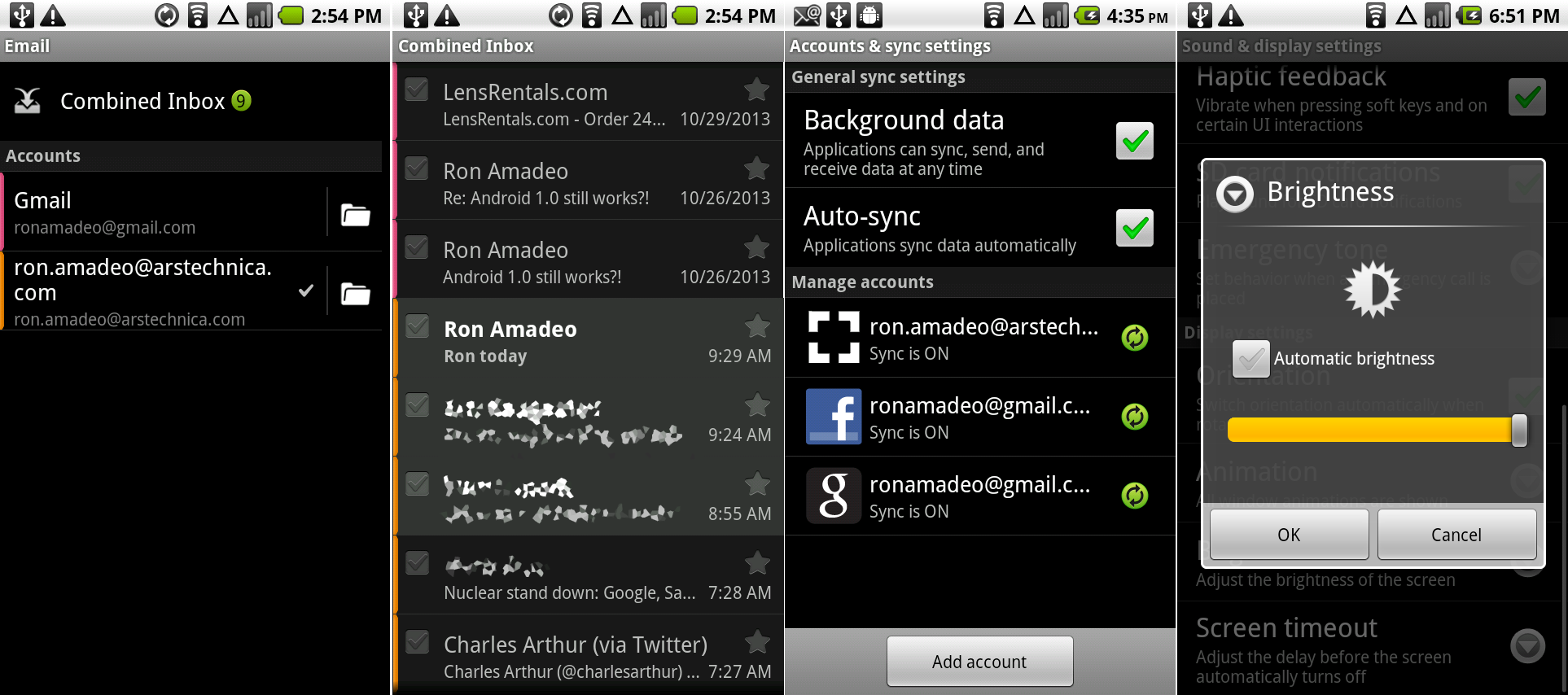

Both screens of the Email app. The first two screenshots show the combined label/inbox view, and the last shows a message.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

The message view was—surprise!—white. Android's e-mail app has historically been a watered-down version of the Gmail app, and you can see that close connection here. The message and compose views were taken directly from Gmail with almost no modifications.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

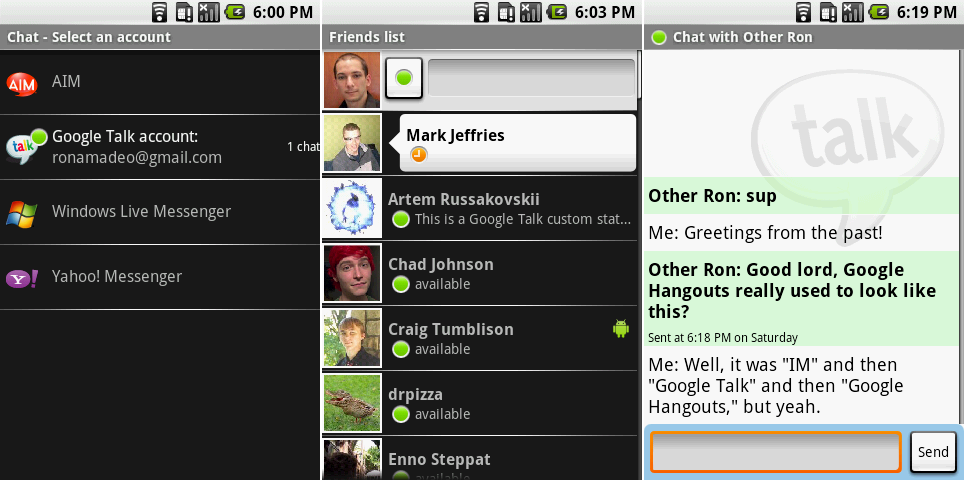

The “IM" applications. Screenshots show the short-lived provider selection screen, the friends list, and a chat.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

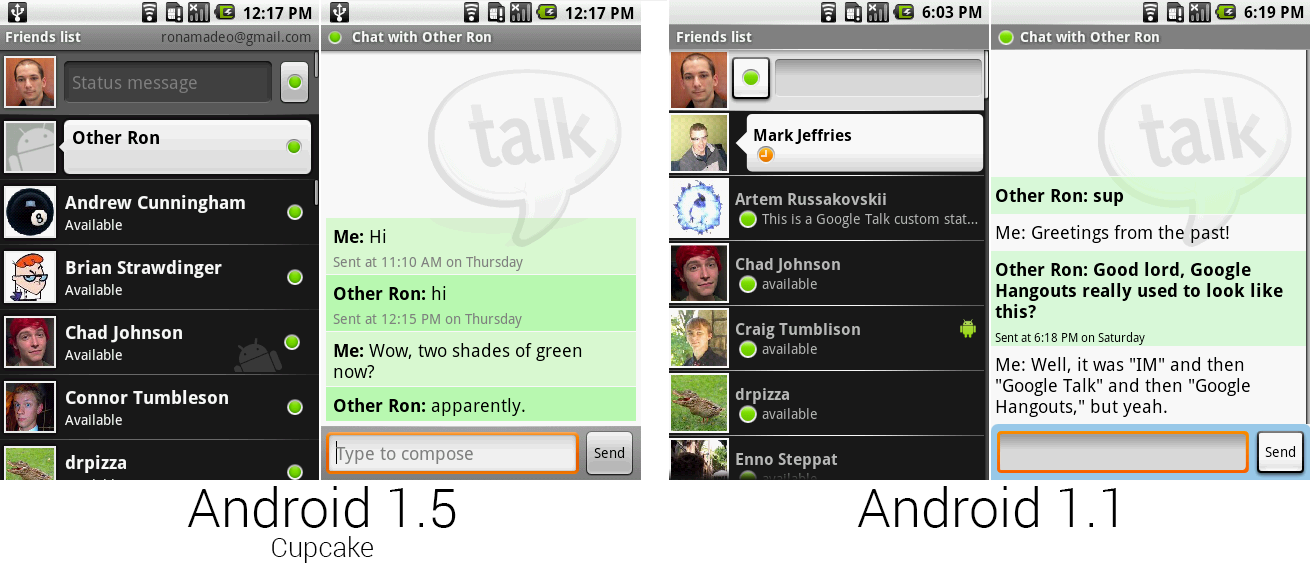

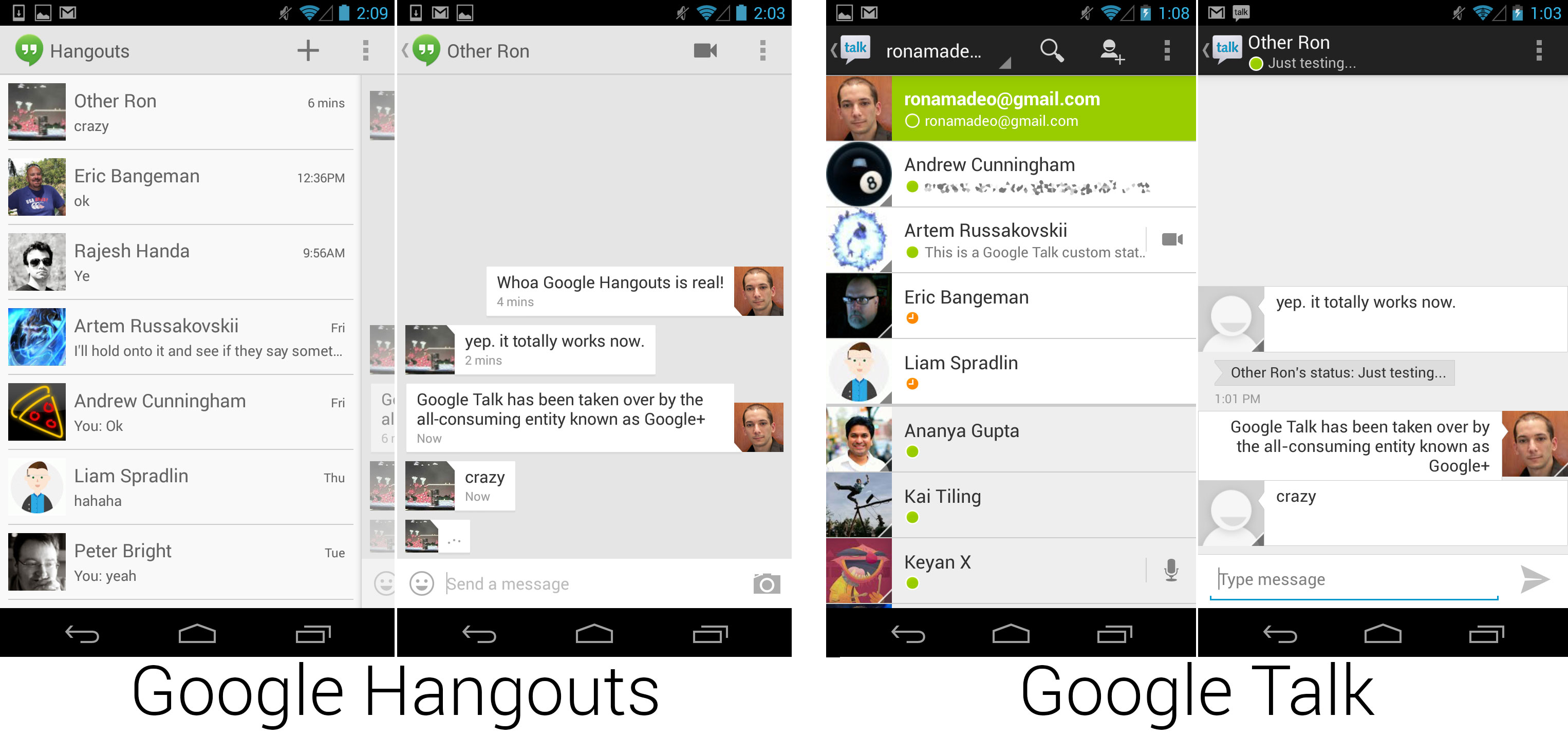

Before Google Hangouts and even before Google Talk, there was "IM"—the only instant messaging client that shipped on Android 1.0. Surprisingly, multiple IM services were supported: users could pick from AIM, Google Talk, Windows Live Messenger, and Yahoo. Remember when OS creators cared about interoperability?

|

||||

|

||||

The friends list was a black background with white speech bubbles for open chats. Presence was indicated with colored circles, and a little Android on the right hand side would indicate that a person was mobile. It's amazing how much more communicative the IM app was than Google Hangouts. Green means the person is using a device they are signed into, yellow means they are signed in but idle, red means they have manually set busy and don't want to be bothered, and gray is offline. Today, Hangouts only shows when a user has the app open or closed.

|

||||

|

||||

The chats interface was clearly based on the Messaging program, and the chat backgrounds were changed from white and blue to white and green. No one changed the color of the blue text entry box, though, so along with the orange highlight effect, this screen used white, green, blue, and orange.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

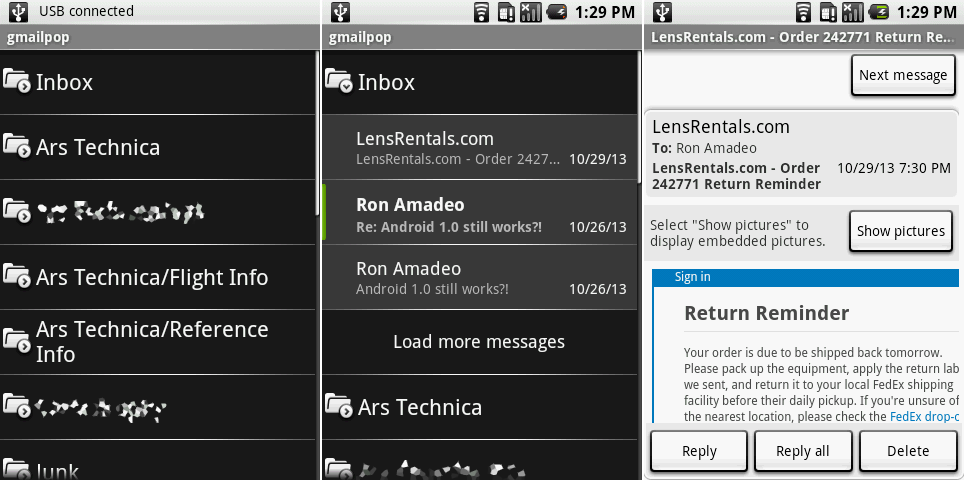

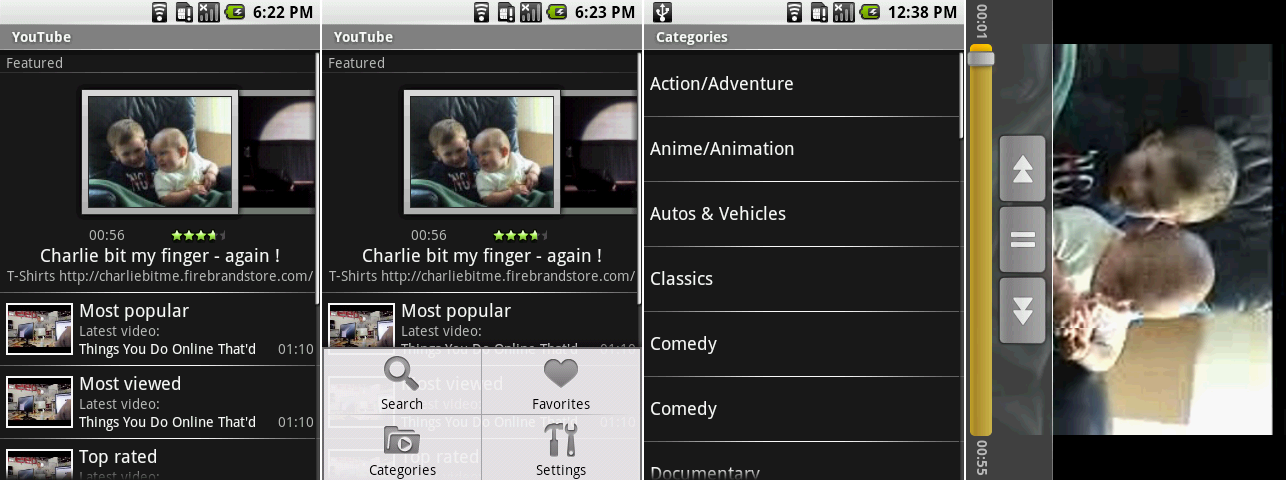

YouTube on Android 1.0. The screens show the main page, the main page with the menu open, the categories screen, and the videos screen.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

YouTube might not have been the mobile sensation it is today with the 320p screen and 3G data speeds of the G1, but Google's video service was present and accounted for on Android 1.0. The main screen looked like a tweaked version of the Android Market, with a horizontally scrolling featured section along the top and vertically scrolling categories along the bottom. Some of Google's category choices were pretty strange: what would the difference be between "Most popular" and "Most viewed?"

|

||||

|

||||

In a sign that Google had no idea how big YouTube would eventually become, one of the video categories was "Most recent." Today, with [100 hours of video][1] uploaded to the site every minute, if this section actually worked it would be an unreadable blur of rapidly scrolling videos.

|

||||

|

||||

The menu housed search, favorites, categories, and settings. Settings (not pictured) was the lamest screen ever, housing one option to clear the search history. Categories was equally barren, showing only a black list of text.

|

||||

|

||||

The last screen shows a video, which only supported horizontal mode. The auto-hiding video controls weirdly had rewind and fast forward buttons, even though there was a seek bar.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

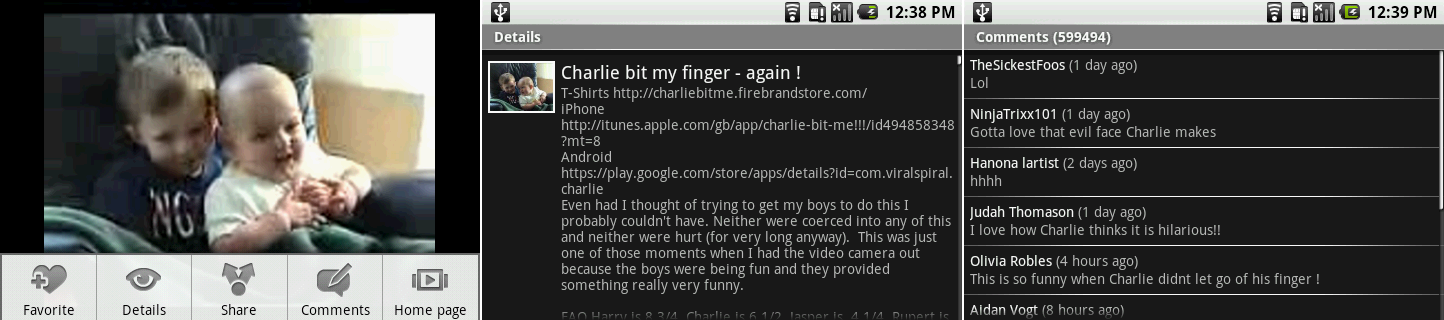

YouTube’s video menu, description page, and comments.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

Additional sections for each video could be brought up by hitting the menu button. Here you could favorite the video, access details, and read comments. All of these screens, like the videos, were locked to horizontal mode.

|

||||

|

||||

"Share" didn't bring up a share dialog yet; it just kicked the link out to a Gmail message. Texting or IMing someone a link wasn't possible. Comments could be read, but you couldn't rate them or post your own. You couldn't rate or like a video either.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

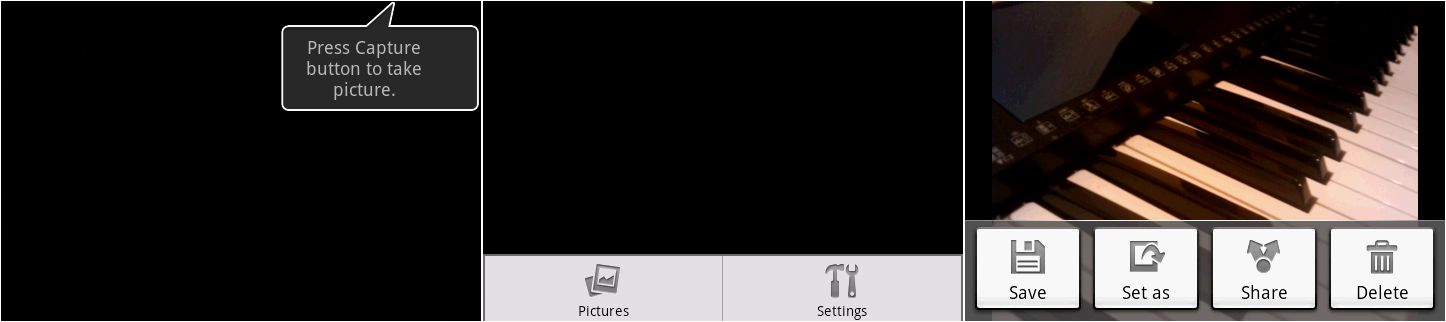

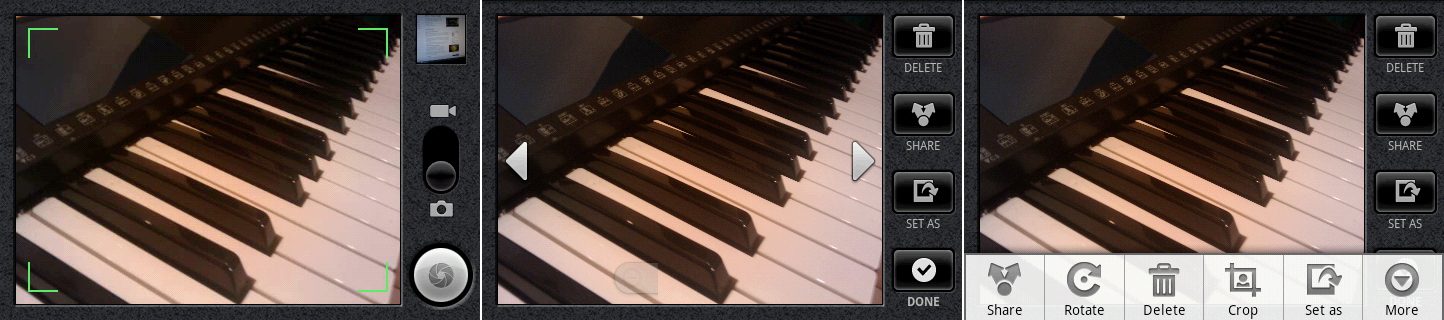

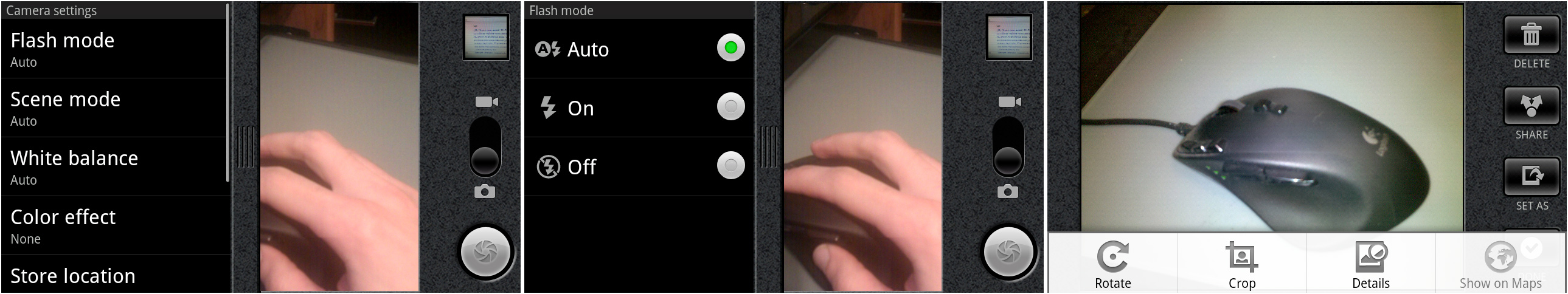

The camera app’s picture taking interface, menu, and photo review mode.

|

||||

Photo by Ron Amadeo

|

||||

|

||||

Real Android on real hardware meant a functional camera app, even if there wasn't much to look at. That black square on the left was the camera interface, which should be showing a viewfinder image, but the SDK screenshot utility can't capture it. The G1 had a hardware camera button (remember those?), so there wasn't a need for an on-screen shutter button. There were no settings for exposure, white balance, or HDR—you could take a picture and that was about it.

|

||||

|

||||

The menu button revealed a meager two options: a way to jump to the Pictures app and Settings screen with two options. The first settings option was whether or not to enable geotagging for pictures, and the second was for a dialog prompt after every capture, which you can see on the right. Also, you could only take pictures—there was no video support yet.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||