mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-02-03 23:40:14 +08:00

Merge pull request #9789 from qhwdw/tr0725

Translated by qhwdw 20180425 Understanding metrics and monitoring with Python - Opensource.com.md

This commit is contained in:

commit

3f6b6643e6

@ -1,489 +0,0 @@

|

|||||||

Translating by qhwdw

|

|

||||||

# Understanding metrics and monitoring with Python

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Image by :

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

opensource.com

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

## Get the newsletter

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Join the 85,000 open source advocates who receive our giveaway alerts and article roundups.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

My reaction when I first came across the terms counter and gauge and the graphs with colors and numbers labeled "mean" and "upper 90" was one of avoidance. It's like I saw them, but I didn't care because I didn't understand them or how they might be useful. Since my job didn't require me to pay attention to them, they remained ignored.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

That was about two years ago. As I progressed in my career, I wanted to understand more about our network applications, and that is when I started learning about metrics.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The three stages of my journey to understanding monitoring (so far) are:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

* Stage 1: What? (Looks elsewhere)

|

|

||||||

* Stage 2: Without metrics, we are really flying blind.

|

|

||||||

* Stage 3: How do we keep from doing metrics wrong?

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

I am currently in Stage 2 and will share what I have learned so far. I'm moving gradually toward Stage 3, and I will offer some of my resources on that part of the journey at the end of this article.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Let's get started!

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

## Software prerequisites

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

More Python Resources

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

* [What is Python?][1]

|

|

||||||

* [Top Python IDEs][2]

|

|

||||||

* [Top Python GUI frameworks][3]

|

|

||||||

* [Latest Python content][4]

|

|

||||||

* [More developer resources][5]

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

All the demos discussed in this article are available on [my GitHub repo][6]. You will need to have docker and docker-compose installed to play with them.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

## Why should I monitor?

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The top reasons for monitoring are:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

* Understanding _normal_ and _abnormal_ system and service behavior

|

|

||||||

* Doing capacity planning, scaling up or down

|

|

||||||

* Assisting in performance troubleshooting

|

|

||||||

* Understanding the effect of software/hardware changes

|

|

||||||

* Changing system behavior in response to a measurement

|

|

||||||

* Alerting when a system exhibits unexpected behavior

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

## Metrics and metric types

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

For our purposes, a **metric** is an _observed_ value of a certain quantity at a given point in _time_. The total of number hits on a blog post, the total number of people attending a talk, the number of times the data was not found in the caching system, the number of logged-in users on your website—all are examples of metrics.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

They broadly fall into three categories:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Counters

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

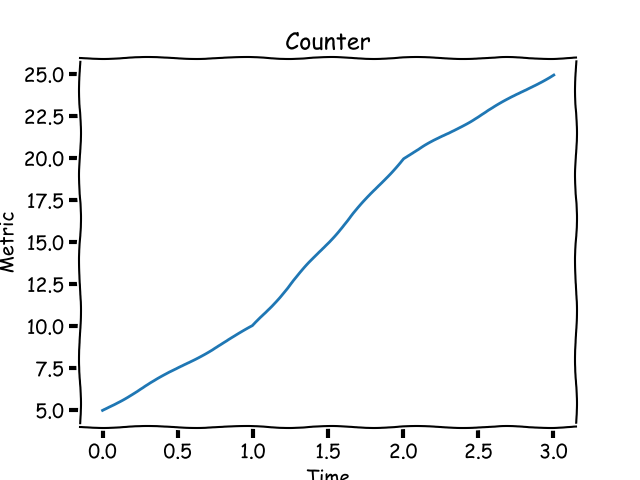

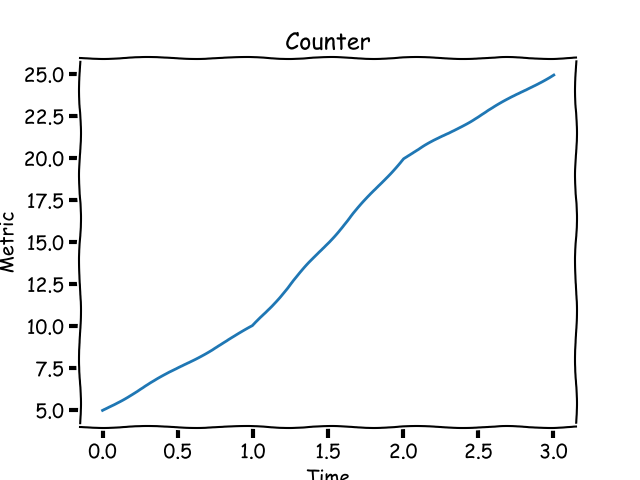

Consider your personal blog. You just published a post and want to keep an eye on how many hits it gets over time, a number that can only increase. This is an example of a **counter** metric. Its value starts at 0 and increases during the lifetime of your blog post. Graphically, a counter looks like this:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

A counter metric always increases.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Gauges

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

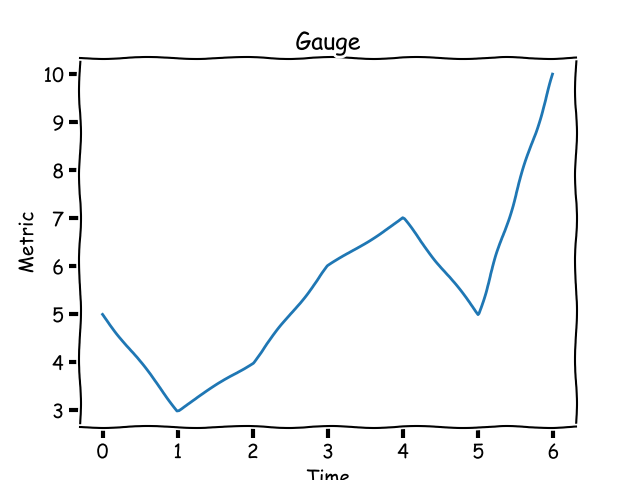

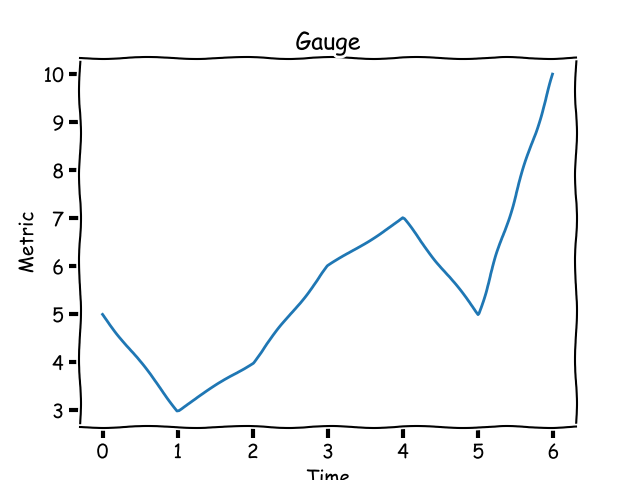

Instead of the total number of hits on your blog post over time, let's say you want to track the number of hits per day or per week. This metric is called a **gauge** and its value can go up or down. Graphically, a gauge looks like this:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

A gauge metric can increase or decrease.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

A gauge's value usually has a _ceiling_ and a _floor_ in a certain time window.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Histograms and timers

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

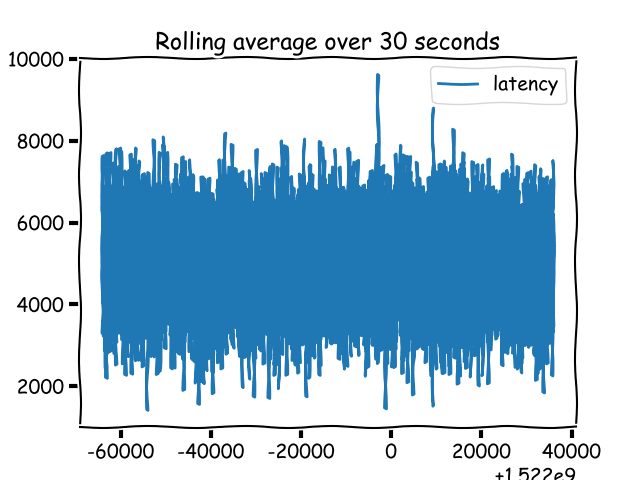

A **histogram** (as Prometheus calls it) or a **timer** (as StatsD calls it) is a metric to track _sampled observations_. Unlike a counter or a gauge, the value of a histogram metric doesn't necessarily show an up or down pattern. I know that doesn't make a lot of sense and may not seem different from a gauge. What's different is what you expect to _do_ with histogram data compared to a gauge. Therefore, the monitoring system needs to know that a metric is a histogram type to allow you to do those things.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

A histogram metric can increase or decrease.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

## Demo 1: Calculating and reporting metrics

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

[Demo 1][7] is a basic web application written using the [Flask][8] framework. It demonstrates how we can _calculate_ and _report_ metrics.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The src directory has the application in app.py with the src/helpers/middleware.py containing the following:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

from flask import request

|

|

||||||

import csv

|

|

||||||

import time

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

def start_timer():

|

|

||||||

request.start_time = time.time()

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

def stop_timer(response):

|

|

||||||

# convert this into milliseconds for statsd

|

|

||||||

resp_time = (time.time() - request.start_time)*1000

|

|

||||||

with open('metrics.csv', 'a', newline='') as f:

|

|

||||||

csvwriter = csv.writer(f)

|

|

||||||

csvwriter.writerow([str(int(time.time())), str(resp_time)])

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

return response

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

def setup_metrics(app):

|

|

||||||

app.before_request(start_timer)

|

|

||||||

app.after_request(stop_timer)

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

When setup_metrics() is called from the application, it configures the start_timer() function to be called before a request is processed and the stop_timer() function to be called after a request is processed but before the response has been sent. In the above function, we write the timestamp and the time it took (in milliseconds) for the request to be processed.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

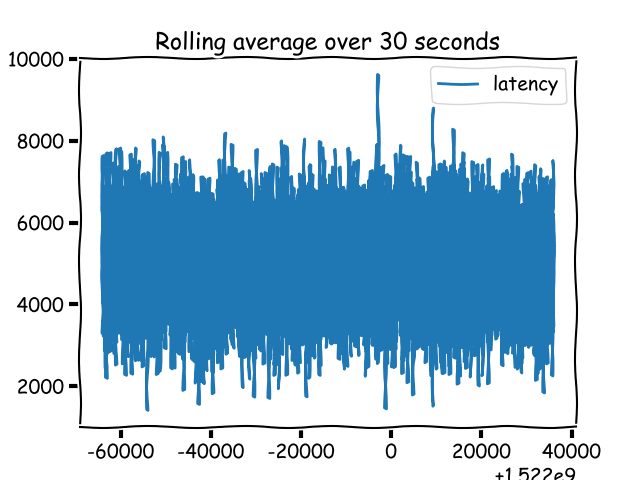

When we run docker-compose up in the demo1 directory, it starts the web application, then a client container that makes a number of requests to the web application. You will see a src/metrics.csv file that has been created with two columns: timestamp and request_latency.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Looking at this file, we can infer two things:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

* There is a lot of data that has been generated

|

|

||||||

* No observation of the metric has any characteristic associated with it

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Without a characteristic associated with a metric observation, we cannot say which HTTP endpoint this metric was associated with or which node of the application this metric was generated from. Hence, we need to qualify each metric observation with the appropriate metadata.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

## Statistics 101

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

If we think back to high school mathematics, there are a few statistics terms we should all recall, even if vaguely, including mean, median, percentile, and histogram. Let's briefly recap them without judging their usefulness, just like in high school.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Mean

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The **mean**, or the average of a list of numbers, is the sum of the numbers divided by the cardinality of the list. The mean of 3, 2, and 10 is (3+2+10)/3 = 5.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Median

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The **median** is another type of average, but it is calculated differently; it is the center numeral in a list of numbers ordered from smallest to largest (or vice versa). In our list above (2, 3, 10), the median is 3. The calculation is not very straightforward; it depends on the number of items in the list.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Percentile

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The **percentile** is a measure that gives us a measure below which a certain (k) percentage of the numbers lie. In some sense, it gives us an _idea_ of how this measure is doing relative to the k percentage of our data. For example, the 95th percentile score of the above list is 9.29999. The percentile measure varies from 0 to 100 (non-inclusive). The _zeroth_ percentile is the minimum score in a set of numbers. Some of you may recall that the median is the 50th percentile, which turns out to be 3.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Some monitoring systems refer to the percentile measure as upper_X where _X_ is the percentile; _upper 90_ refers to the value at the 90th percentile.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Quantile

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The **q-Quantile** is a measure that ranks q_N_ in a set of _N_ numbers. The value of **q** ranges between 0 and 1 (both inclusive). When **q** is 0.5, the value is the median. The relationship between the quantile and percentile is that the measure at **q** quantile is equivalent to the measure at **100_q_** percentile.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Histogram

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

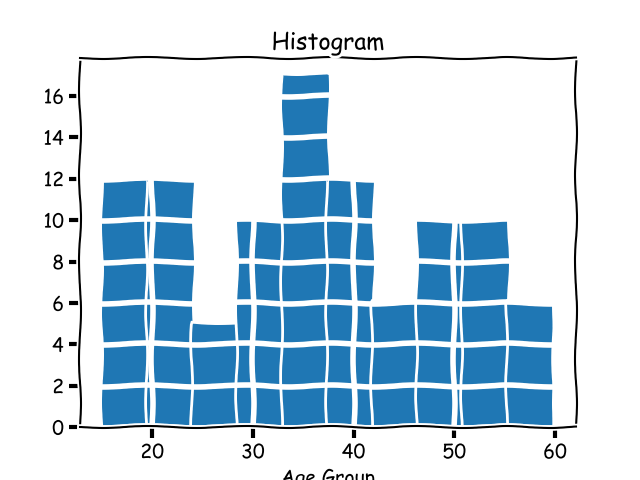

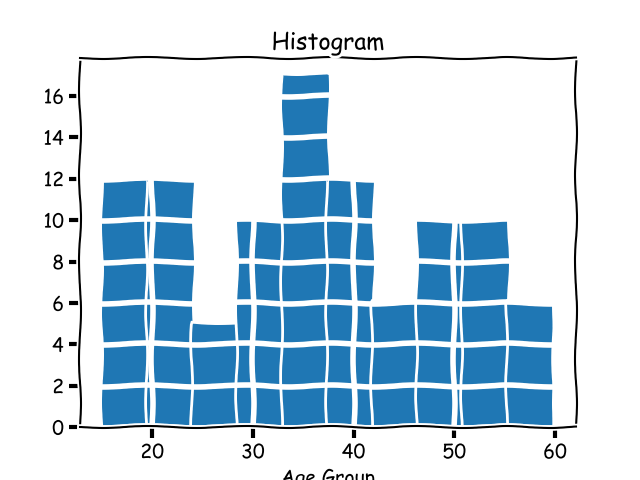

The metric **histogram**, which we learned about earlier, is an _implementation detail_ of monitoring systems. In statistics, a histogram is a graph that groups data into _buckets_. Let's consider a different, contrived example: the ages of people reading your blog. If you got a handful of this data and wanted a rough idea of your readers' ages by group, plotting a histogram would show you a graph like this:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Cumulative histogram

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

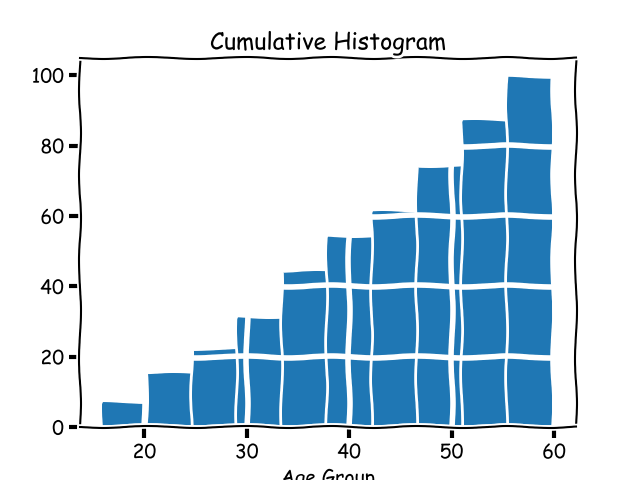

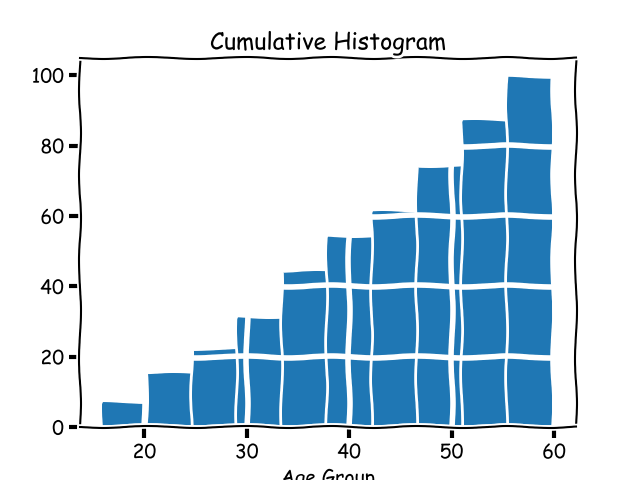

A **cumulative histogram** is a histogram where each bucket's count includes the count of the previous bucket, hence the name _cumulative_. A cumulative histogram for the above dataset would look like this:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Why do we need statistics?

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

In Demo 1 above, we observed that there is a lot of data that is generated when we report metrics. We need statistics when working with metrics because there are just too many of them. We don't care about individual values, rather overall behavior. We expect the behavior the values exhibit is a proxy of the behavior of the system under observation.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

## Demo 2: Adding characteristics to metrics

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

In our Demo 1 application above, when we calculate and report a request latency, it refers to a specific request uniquely identified by few _characteristics_. Some of these are:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

* The HTTP endpoint

|

|

||||||

* The HTTP method

|

|

||||||

* The identifier of the host/node where it's running

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

If we attach these characteristics to a metric observation, we have more context around each metric. Let's explore adding characteristics to our metrics in [Demo 2][9].

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The src/helpers/middleware.py file now writes multiple columns to the CSV file when writing metrics:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

node_ids = ['10.0.1.1', '10.1.3.4']

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

def start_timer():

|

|

||||||

request.start_time = time.time()

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

def stop_timer(response):

|

|

||||||

# convert this into milliseconds for statsd

|

|

||||||

resp_time = (time.time() - request.start_time)*1000

|

|

||||||

node_id = node_ids[random.choice(range(len(node_ids)))]

|

|

||||||

with open('metrics.csv', 'a', newline='') as f:

|

|

||||||

csvwriter = csv.writer(f)

|

|

||||||

csvwriter.writerow([

|

|

||||||

str(int(time.time())), 'webapp1', node_id,

|

|

||||||

request.endpoint, request.method, str(response.status_code),

|

|

||||||

str(resp_time)

|

|

||||||

])

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

return response

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Since this is a demo, I have taken the liberty of reporting random IPs as the node IDs when reporting the metric. When we run docker-compose up in the demo2 directory, it will result in a CSV file with multiple columns.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Analyzing metrics with pandas

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

We'll now analyze this CSV file with [pandas][10]. Running docker-compose up will print a URL that we will use to open a [Jupyter][11] session. Once we upload the Analysis.ipynb notebook into the session, we can read the CSV file into a pandas DataFrame:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

import pandas as pd

|

|

||||||

metrics = pd.read_csv('/data/metrics.csv', index_col=0)

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The index_col specifies that we want to use the timestamp as the index.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Since each characteristic we add is a column in the DataFrame, we can perform grouping and aggregation based on these columns:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

import numpy as np

|

|

||||||

metrics.groupby(['node_id', 'http_status']).latency.aggregate(np.percentile, 99.999)

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Please refer to the Jupyter notebook for more example analysis on the data.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

## What should I monitor?

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

A software system has a number of variables whose values change during its lifetime. The software is running in some sort of an operating system, and operating system variables change as well. In my opinion, the more data you have, the better it is when something goes wrong.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Key operating system metrics I recommend monitoring are:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

* CPU usage

|

|

||||||

* System memory usage

|

|

||||||

* File descriptor usage

|

|

||||||

* Disk usage

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Other key metrics to monitor will vary depending on your software application.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Network applications

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

If your software is a network application that listens to and serves client requests, the key metrics to measure are:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

* Number of requests coming in (counter)

|

|

||||||

* Unhandled errors (counter)

|

|

||||||

* Request latency (histogram/timer)

|

|

||||||

* Queued time, if there is a queue in your application (histogram/timer)

|

|

||||||

* Queue size, if there is a queue in your application (gauge)

|

|

||||||

* Worker processes/threads usage (gauge)

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

If your network application makes requests to other services in the context of fulfilling a client request, it should have metrics to record the behavior of communications with those services. Key metrics to monitor include number of requests, request latency, and response status.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### HTTP web application backends

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

HTTP applications should monitor all the above. In addition, they should keep granular data about the count of non-200 HTTP statuses grouped by all the other HTTP status codes. If your web application has user signup and login functionality, it should have metrics for those as well.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Long-running processes

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Long-running processes such as Rabbit MQ consumer or task-queue workers, although not network servers, work on the model of picking up a task and processing it. Hence, we should monitor the number of requests processed and the request latency for those processes.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

No matter the application type, each metric should have appropriate **metadata** associated with it.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

## Integrating monitoring in a Python application

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

There are two components involved in integrating monitoring into Python applications:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

* Updating your application to calculate and report metrics

|

|

||||||

* Setting up a monitoring infrastructure to house the application's metrics and allow queries to be made against them

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The basic idea of recording and reporting a metric is:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

def work():

|

|

||||||

requests += 1

|

|

||||||

# report counter

|

|

||||||

start_time = time.time()

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

# < do the work >

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

# calculate and report latency

|

|

||||||

work_latency = time.time() - start_time

|

|

||||||

...

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Considering the above pattern, we often take advantage of _decorators_, _context managers_, and _middleware_ (for network applications) to calculate and report metrics. In Demo 1 and Demo 2, we used decorators in a Flask application.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Pull and push models for metric reporting

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Essentially, there are two patterns for reporting metrics from a Python application. In the _pull_ model, the monitoring system "scrapes" the application at a predefined HTTP endpoint. In the _push_ model, the application sends the data to the monitoring system.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

An example of a monitoring system working in the _pull_ model is [Prometheus][12]. [StatsD][13] is an example of a monitoring system where the application _pushes_ the metrics to the system.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Integrating StatsD

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

To integrate StatsD into a Python application, we would use the [StatsD Python client][14], then update our metric-reporting code to push data into StatsD using the appropriate library calls.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

First, we need to create a client instance:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

statsd = statsd.StatsClient(host='statsd', port=8125, prefix='webapp1')

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The prefix keyword argument will add the specified prefix to all the metrics reported via this client.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Once we have the client, we can report a value for a timer using:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

statsd.timing(key, resp_time)

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

To increment a counter:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

statsd.incr(key)

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

To associate metadata with a metric, a key is defined as metadata1.metadata2.metric, where each metadataX is a field that allows aggregation and grouping.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The demo application [StatsD][15] is a complete example of integrating a Python Flask application with statsd.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Integrating Prometheus

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

To use the Prometheus monitoring system, we will use the [Promethius Python client][16]. We will first create objects of the appropriate metric class:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

REQUEST_LATENCY = Histogram('request_latency_seconds', 'Request latency',

|

|

||||||

['app_name', 'endpoint']

|

|

||||||

)

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The third argument in the above statement is the labels associated with the metric. These labels are what defines the metadata associated with a single metric value.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

To record a specific metric observation:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

REQUEST_LATENCY.labels('webapp', request.path).observe(resp_time)

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The next step is to define an HTTP endpoint in our application that Prometheus can scrape. This is usually an endpoint called /metrics:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

@app.route('/metrics')

|

|

||||||

def metrics():

|

|

||||||

return Response(prometheus_client.generate_latest(), mimetype=CONTENT_TYPE_LATEST)

|

|

||||||

```

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The demo application [Prometheus][17] is a complete example of integrating a Python Flask application with prometheus.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Which is better: StatsD or Prometheus?

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The natural next question is: Should I use StatsD or Prometheus? I have written a few articles on this topic, and you may find them useful:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

* [Your options for monitoring multi-process Python applications with Prometheus][18]

|

|

||||||

* [Monitoring your synchronous Python web applications using Prometheus][19]

|

|

||||||

* [Monitoring your asynchronous Python web applications using Prometheus][20]

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

## Ways to use metrics

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

We've learned a bit about why we want to set up monitoring in our applications, but now let's look deeper into two of them: alerting and autoscaling.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Using metrics for alerting

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

A key use of metrics is creating alerts. For example, you may want to send an email or pager notification to relevant people if the number of HTTP 500s over the past five minutes increases. What we use for setting up alerts depends on our monitoring setup. For Prometheus we can use [Alertmanager][21] and for StatsD, we use [Nagios][22].

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Using metrics for autoscaling

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Not only can metrics allow us to understand if our current infrastructure is over- or under-provisioned, they can also help implement autoscaling policies in a cloud infrastructure. For example, if worker process usage on our servers routinely hits 90% over the past five minutes, we may need to horizontally scale. How we would implement scaling depends on the cloud infrastructure. AWS Auto Scaling, by default, allows scaling policies based on system CPU usage, network traffic, and other factors. However, to use application metrics for scaling up or down, we must publish [custom CloudWatch metrics][23].

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

## Application monitoring in a multi-service architecture

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

When we go beyond a single application architecture, such that a client request can trigger calls to multiple services before a response is sent back, we need more from our metrics. We need a unified view of latency metrics so we can see how much time each service took to respond to the request. This is enabled with [distributed tracing][24].

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

You can see an example of distributed tracing in Python in my blog post [Introducing distributed tracing in your Python application via Zipkin][25].

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

## Points to remember

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

In summary, make sure to keep the following things in mind:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

* Understand what a metric type means in your monitoring system

|

|

||||||

* Know in what unit of measurement the monitoring system wants your data

|

|

||||||

* Monitor the most critical components of your application

|

|

||||||

* Monitor the behavior of your application in its most critical stages

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

The above assumes you don't have to manage your monitoring systems. If that's part of your job, you have a lot more to think about!

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

## Other resources

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Following are some of the resources I found very useful along my monitoring education journey:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### General

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

* [Monitoring distributed systems][26]

|

|

||||||

* [Observability and monitoring best practices][27]

|

|

||||||

* [Who wants seconds?][28]

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### StatsD/Graphite

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

* [StatsD metric types][29]

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

### Prometheus

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

* [Prometheus metric types][30]

|

|

||||||

* [How does a Prometheus gauge work?][31]

|

|

||||||

* [Why are Prometheus histograms cumulative?][32]

|

|

||||||

* [Monitoring batch jobs in Python][33]

|

|

||||||

* [Prometheus: Monitoring at SoundCloud][34]

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

## Avoiding mistakes (i.e., Stage 3 learnings)

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

As we learn the basics of monitoring, it's important to keep an eye on the mistakes we don't want to make. Here are some insightful resources I have come across:

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

* [How not to measure latency][35]

|

|

||||||

* [Histograms with Prometheus: A tale of woe][36]

|

|

||||||

* [Why averages suck and percentiles are great][37]

|

|

||||||

* [Everything you know about latency is wrong][38]

|

|

||||||

* [Who moved my 99th percentile latency?][39]

|

|

||||||

* [Logs and metrics and graphs][40]

|

|

||||||

* [HdrHistogram: A better latency capture method][41]

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

---

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

To learn more, attend Amit Saha's talk, [Counter, gauge, upper 90—Oh my!][42], at [PyCon Cleveland 2018][43].

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

## About the author

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

[][44]

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

Amit Saha \- I am a software engineer interested in infrastructure, monitoring and tooling. I am the author of "Doing Math with Python" and creator and the maintainer of Fedora Scientific Spin.

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

[More about me][45]

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

* [Learn how you can contribute][46]

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

---

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

via: [https://opensource.com/article/18/4/metrics-monitoring-and-python][47]

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

作者: [Amit Saha][48] 选题者: [@lujun9972][49] 译者: [译者ID][50] 校对: [校对者ID][51]

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

本文由 [LCTT][52] 原创编译,[Linux中国][53] 荣誉推出

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

[1]: https://opensource.com/resources/python?intcmp=7016000000127cYAAQ

|

|

||||||

[2]: https://opensource.com/resources/python/ides?intcmp=7016000000127cYAAQ

|

|

||||||

[3]: https://opensource.com/resources/python/gui-frameworks?intcmp=7016000000127cYAAQ

|

|

||||||

[4]: https://opensource.com/tags/python?intcmp=7016000000127cYAAQ

|

|

||||||

[5]: https://developers.redhat.com/?intcmp=7016000000127cYAAQ

|

|

||||||

[6]: https://github.com/amitsaha/python-monitoring-talk

|

|

||||||

[7]: https://github.com/amitsaha/python-monitoring-talk/tree/master/demo1

|

|

||||||

[8]: http://flask.pocoo.org/

|

|

||||||

[9]: https://github.com/amitsaha/python-monitoring-talk/tree/master/demo2

|

|

||||||

[10]: https://pandas.pydata.org/

|

|

||||||

[11]: http://jupyter.org/

|

|

||||||

[12]: https://prometheus.io/

|

|

||||||

[13]: https://github.com/etsy/statsd

|

|

||||||

[14]: https://pypi.python.org/pypi/statsd

|

|

||||||

[15]: https://github.com/amitsaha/python-monitoring-talk/tree/master/statsd

|

|

||||||

[16]: https://pypi.python.org/pypi/prometheus_client

|

|

||||||

[17]: https://github.com/amitsaha/python-monitoring-talk/tree/master/prometheus

|

|

||||||

[18]: http://echorand.me/your-options-for-monitoring-multi-process-python-applications-with-prometheus.html

|

|

||||||

[19]: https://blog.codeship.com/monitoring-your-synchronous-python-web-applications-using-prometheus/

|

|

||||||

[20]: https://blog.codeship.com/monitoring-your-asynchronous-python-web-applications-using-prometheus/

|

|

||||||

[21]: https://github.com/prometheus/alertmanager

|

|

||||||

[22]: https://www.nagios.org/about/overview/

|

|

||||||

[23]: https://docs.aws.amazon.com/AmazonCloudWatch/latest/monitoring/publishingMetrics.html

|

|

||||||

[24]: http://opentracing.io/documentation/

|

|

||||||

[25]: http://echorand.me/introducing-distributed-tracing-in-your-python-application-via-zipkin.html

|

|

||||||

[26]: https://landing.google.com/sre/book/chapters/monitoring-distributed-systems.html

|

|

||||||

[27]: http://www.integralist.co.uk/posts/monitoring-best-practices/?imm_mid=0fbebf&cmp=em-webops-na-na-newsltr_20180309

|

|

||||||

[28]: https://www.robustperception.io/who-wants-seconds/

|

|

||||||

[29]: https://github.com/etsy/statsd/blob/master/docs/metric_types.md

|

|

||||||

[30]: https://prometheus.io/docs/concepts/metric_types/

|

|

||||||

[31]: https://www.robustperception.io/how-does-a-prometheus-gauge-work/

|

|

||||||

[32]: https://www.robustperception.io/why-are-prometheus-histograms-cumulative/

|

|

||||||

[33]: https://www.robustperception.io/monitoring-batch-jobs-in-python/

|

|

||||||

[34]: https://developers.soundcloud.com/blog/prometheus-monitoring-at-soundcloud

|

|

||||||

[35]: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lJ8ydIuPFeU&feature=youtu.be

|

|

||||||

[36]: http://linuxczar.net/blog/2017/06/15/prometheus-histogram-2/

|

|

||||||

[37]: https://www.dynatrace.com/news/blog/why-averages-suck-and-percentiles-are-great/

|

|

||||||

[38]: https://bravenewgeek.com/everything-you-know-about-latency-is-wrong/

|

|

||||||

[39]: https://engineering.linkedin.com/performance/who-moved-my-99th-percentile-latency

|

|

||||||

[40]: https://grafana.com/blog/2016/01/05/logs-and-metrics-and-graphs-oh-my/

|

|

||||||

[41]: http://psy-lob-saw.blogspot.com.au/2015/02/hdrhistogram-better-latency-capture.html

|

|

||||||

[42]: https://us.pycon.org/2018/schedule/presentation/133/

|

|

||||||

[43]: https://us.pycon.org/2018/

|

|

||||||

[44]: https://opensource.com/users/amitsaha

|

|

||||||

[45]: https://opensource.com/users/amitsaha

|

|

||||||

[46]: https://opensource.com/participate

|

|

||||||

[47]: https://opensource.com/article/18/4/metrics-monitoring-and-python

|

|

||||||

[48]: https://opensource.com/users/amitsaha

|

|

||||||

[49]: https://github.com/lujun9972

|

|

||||||

[50]: https://github.com/译者ID

|

|

||||||

[51]: https://github.com/校对者ID

|

|

||||||

[52]: https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject

|

|

||||||

[53]: https://linux.cn/

|

|

||||||

@ -0,0 +1,488 @@

|

|||||||

|

# 理解指标和使用 Python 去监视

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Image by :

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

opensource.com

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 获取订阅

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

加入我们吧,我们有 85,000 位开源支持者,加入后会定期接收到我们免费提供的提示和文章摘要。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

当我第一次看到术语“计数器”和“计量器”和使用颜色及标记着“意思”和“最大 90”的数字图表时,我的反应之一是逃避。就像我看到它们一样,我并不感兴趣,因为我不理解它们是干什么的或如何去使用。因为我的工作不需要我去注意它们,它们被我完全无视。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

这都是在两年以前的事了。随着我的职业发展,我希望去了解更多关于我们的网络应用程序的知识,而那个时候就是我开始去学习指标的时候。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

我的理解监视的学习之旅共有三个阶段(到目前为止),它们是:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

* 阶段 1:什么?(看别处)

|

||||||

|

* 阶段 2:没有指标,我们真的是瞎撞。

|

||||||

|

* 阶段 3:出现不合理的指标我们该如何做?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

我现在处于阶段 2,我将分享到目前为止我学到了些什么。我正在向阶段 3 进发,在本文结束的位置我提供了一些我正在使用的学习资源。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

我们开始吧!

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 需要的软件

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

更多关于 Python 的资源

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

* [Python 是什么?][1]

|

||||||

|

* [Python IDE 排行榜][2]

|

||||||

|

* [Python GUI 框架排行榜][3]

|

||||||

|

* [最新的 Python 主题][4]

|

||||||

|

* [更多开发者资源][5]

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

在文章中讨论时用到的 demo 都可以在 [我的 GitHub 仓库][6] 中找到。你需要安装 docker 和 docker-compose 才能使用它们。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 为什么要监视?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

关于监视的主要原因是:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

* 理解 _正常的_ 和 _不正常的_ 系统和服务的特征

|

||||||

|

* 做容量规划、弹性伸缩

|

||||||

|

* 有助于排错

|

||||||

|

* 了解软件/硬件改变的效果

|

||||||

|

* 测量响应中的系统行为变化

|

||||||

|

* 当系统出现意外行为时发出警报

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 指标和指标类型

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

从我们的用途来看,一个**指标**就是在一个给定时间点上的某些数量的 _测量_ 值。博客文章的总点击次数、参与讨论的总人数、在缓存系统中数据没有被找到的次数、你的网站上的已登录用户数 —— 这些都是指标的例子。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

它们总体上可以分为三类:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 计数器

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

以你的个人博客为例。你发布一篇文章后,过一段时间后,你希望去了解有多少点击量,数字只会增加。这就是一个**计数器**指标。在你的博客文章的生命周期中,它的值从 0 开始增加。用图表来表示,一个计数器看起来应该像下面的这样:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

一个计数器指标总是在增加的。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 计量器

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

如果你想去跟踪你的博客每天或每周的点击量,而不是基于时间的总点击量。这种指标被称为一个**计量器**,它的值可上可下。用图表来表示,一个计量器看起来应该像下面的样子:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

一个计量器指标可以增加或减少。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

一个计量器的值在某些时间窗口内通常有一个_最大值_ 和 _最小值_ 。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 柱状图和计时器

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

一个**柱状图**(在 Prometheus 中这么叫它)或一个**计时器**(在 StatsD 中这么叫它)是跟踪已采样的_观测结果_ 的指标。不像一个计数器类或计量器类指标,柱状图指标的值并不是显示为上或下的样式。我知道这可能并没有太多的意义,并且可能和一个计量器图看上去没有什么不同。它们的这同之处在于,你期望使用柱状图数据来做什么,而不是与一个计量器图做比较。因此,监视系统需要知道那个指标是一个柱状图类型,它允许你去做哪些事情。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

一个柱状图指标可以增加或减少。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Demo 1:计算和报告指标

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[Demo 1][7] 是使用 [Flask][8] 框架写的一个基本的 web 应用程序。它演示了我们如何去 _计算_ 和 _报告_ 指标。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

在 src 目录中有 `app.py` 和 `src/helpers/middleware.py` 应用程序,包含以下内容:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

from flask import request

|

||||||

|

import csv

|

||||||

|

import time

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

def start_timer():

|

||||||

|

request.start_time = time.time()

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

def stop_timer(response):

|

||||||

|

# convert this into milliseconds for statsd

|

||||||

|

resp_time = (time.time() - request.start_time)*1000

|

||||||

|

with open('metrics.csv', 'a', newline='') as f:

|

||||||

|

csvwriter = csv.writer(f)

|

||||||

|

csvwriter.writerow([str(int(time.time())), str(resp_time)])

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

return response

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

def setup_metrics(app):

|

||||||

|

app.before_request(start_timer)

|

||||||

|

app.after_request(stop_timer)

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

当在应用程序中调用 `setup_metrics()` 时,它在请求处理之前被配置为调用 `start_timer()` 函数,然后在请求处理之后、响应发送之前调用 `stop_timer()` 函数。在上面的函数中,我们写了时间戳并用它来计算处理请求所花费的时间。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

当我们在 demo1 目录中的 docker-compose 上开始去启动 web 应用程序,然后在一个客户端容器中生成一些对 web 应用程序的请求。你将会看到创建了一个 `src/metrics.csv` 文件,它有两个字段:timestamp 和 request_latency。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

通过查看这个文件,我们可以推断出两件事情:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

* 生成了很多数据

|

||||||

|

* 没有观测到任何与指标相关的特征

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

没有观测到与指标相关的特征,我们就不能说这个指标与哪个 HTTP 端点有关联,或这个指标是由哪个应用程序的节点所生成的。因此,我们需要使用合适的元数据去限定每个观测指标。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Statistics 101~~(译者注:这是一本统计学入门教材的名字)~~

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

假如我们回到高中数学,我们应该回忆起一些统计术语,虽然不太确定,但应该包括平均数、中位数、百分位、和柱状图。我们来简要地回顾一下它们,不用去管他们的用法,就像是在上高中一样。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 平均数

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

**平均数**,或一系列数字的平均值,是将数字汇总然后除以列表的个数。3、2、和 10 的平均数是 (3+2+10)/3 = 5。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 中位数

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

**中位数**是另一种类型的平均,但它的计算方式不同;它是列表从小到大排序(反之亦然)后取列表的中间数字。以我们上面的列表中(2、3、10),中位数是 3。计算并不简单,它取决于列表中数字的个数。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 百分位

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

**百分位**是指那个百(千)分比数字低于我们给定的百分数的程度。在一些场景中,百分位是指这个测量值低于我们数据的百(千)分比数字的程度。比如,上面列表中 95% 是 9.29999。百分位的测量范围是 0 到 100(不包括)。0% 是一组数字的最小分数。你可能会想到它的中位数是 50%,它的结果是 3。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

一些监视系统将百分位称为 `upper_X`,其中 _X_ 就是百分位;`_upper 90_` 指的是值在 90%的位置。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 分位数

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

**q-Quantile** 是将有 _N_ 个数的集合等分为 q_N_ 个集合。**q** 的取值范围为 0 到 1(全部都包括)。当 **q** 取值为 0.5 时,值就是中位数。分位数和百分位数的关系是,分位数值 **q** 等于 **100_q_** 百分位值。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 柱状图

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

**柱状图**这个指标,我们早期学习过,它是监视系统中一个_详细的实现_。在统计学中,一个柱状图是一个将数据分组为 _桶_ 的图表。我们来考虑一个人为的、不同的示例:阅读你的博客的人的年龄。如果你有一些这样的数据,并想将它进行大致的分组,绘制成的柱状图将看起来像下面的这样:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 累积柱状图

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

一个**累积柱状图**也是一个柱状图,它的每个桶的数包含前一个桶的数,因此命名为_累积_。将上面的数据集做成累积柱状图后,看起来应该是这样的:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 我们为什么需要做统计?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

在上面的 Demo 1 中,我们注意到在我们报告指标时,这里生成了许多数据。当我们将它用于指标时我们需要做统计,因为它们实在是太多了。我们需要的是整体行为,我们没法去处理单个值。我们预期展现出来的值的行为应该是代表我们观察的系统的行为。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## Demo 2:指标上增加特征

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

在我们上面的的 Demo 1 应用程序中,当我们计算和报告一个请求的延迟时,它指向了一个由一些_特征_ 唯一标识的特定请求。下面是其中一些:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

* HTTP 端点

|

||||||

|

* HTTP 方法

|

||||||

|

* 运行它的主机/节点的标识符

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

如果我们将这些特征附加到要观察的指标上,每个指标将有更多的内容。我们来解释一下 [Demo 2][9] 中添加到我们的指标上的特征。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

在写入指标时,src/helpers/middleware.py 文件将在 CSV 文件中写入多个列:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

node_ids = ['10.0.1.1', '10.1.3.4']

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

def start_timer():

|

||||||

|

request.start_time = time.time()

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

def stop_timer(response):

|

||||||

|

# convert this into milliseconds for statsd

|

||||||

|

resp_time = (time.time() - request.start_time)*1000

|

||||||

|

node_id = node_ids[random.choice(range(len(node_ids)))]

|

||||||

|

with open('metrics.csv', 'a', newline='') as f:

|

||||||

|

csvwriter = csv.writer(f)

|

||||||

|

csvwriter.writerow([

|

||||||

|

str(int(time.time())), 'webapp1', node_id,

|

||||||

|

request.endpoint, request.method, str(response.status_code),

|

||||||

|

str(resp_time)

|

||||||

|

])

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

return response

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

因为这只是一个演示,在报告指标时,我们将随意的报告一些随机 IP 作为节点的 ID。当我们在 demo2 目录下运行 docker-compose 时,我们的结果将是一个有多个列的 CSV 文件。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 用 pandas 分析指标

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

我们将使用 [pandas][10] 去分析这个 CSV 文件。运行中的 docker-compose 将打印出一个 URL,我们将使用它来打开一个 [Jupyter][11] 会话。一旦我们上传 `Analysis.ipynb notebook` 到会话中,我们就可以将 CSV 文件读入到一个 pandas 数据帧中:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

import pandas as pd

|

||||||

|

metrics = pd.read_csv('/data/metrics.csv', index_col=0)

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

index_col 指定时间戳作为索引。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

因为每个特征我们都在数据帧中添加一个列,因此我们可以基于这些列进行分组和聚合:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

import numpy as np

|

||||||

|

metrics.groupby(['node_id', 'http_status']).latency.aggregate(np.percentile, 99.999)

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

更多内容请参考 Jupyter notebook 在数据上的分析示例。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 我应该监视什么?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

一个软件系统有许多的变量,这些变量的值在它的生命周期中不停地发生变化。软件是运行在某种操作系统上的,而操作系统同时也在不停地变化。在我看来,当某些东西出错时,你所拥有的数据越多越好。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

我建议去监视的关键操作系统指标有:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

* CPU 使用

|

||||||

|

* 系统内存使用

|

||||||

|

* 文件描述符使用

|

||||||

|

* 磁盘使用

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

还需要监视的其它关键指标根据你的软件应用程序不同而不同。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 网络应用程序

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

如果你的软件是一个监听客户端请求和为它提供服务的网络应用程序,需要测量的关键指标还有:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

* 入站请求数(计数器)

|

||||||

|

* 未处理的错误(计数器)

|

||||||

|

* 请求延迟(柱状图/计时器)

|

||||||

|

* 队列时间,如果在你的应用程序中有队列(柱状图/计时器)

|

||||||

|

* 队列大小,如果在你的应用程序中有队列(计量器)

|

||||||

|

* 工作进程/线程使用(计量器)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

如果你的网络应用程序在一个客户端请求的环境中向其它服务发送请求,那么它应该有一个指标去记录它与那个服务之间的通讯行为。需要监视的关键指标包括请求数、请求延迟、和响应状态。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### HTTP web 应用程序后端

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

HTTP 应用程序应该监视上面所列出的全部指标。除此之外,还应该按 HTTP 状态代码分组监视所有非 200 的 HTTP 状态代码的大致数据。如果你的 web 应用程序有用户注册和登录功能,同时也应该为这个功能设置指标。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 长周期运行的进程

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

长周期运行的进程如 Rabbit MQ 消费者或 task-queue 工作进程,虽然它们不是网络服务,它们以选取一个任务并处理它的工作模型来运行。因此,我们应该监视请求的进程数和这些进程的请求延迟。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

不管是什么类型的应用程序,都有指标与合适的**元数据**相关联。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 将监视集成到一个 Python 应用程序中

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

将监视集成到 Python 应用程序中需要涉及到两个组件:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

* 更新你的应用程序去计算和报告指标

|

||||||

|

* 配置一个监视基础设施来容纳应用程序的指标,并允许去查询它们

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

下面是记录和报告指标的基本思路:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

def work():

|

||||||

|

requests += 1

|

||||||

|

# report counter

|

||||||

|

start_time = time.time()

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

# < do the work >

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

# calculate and report latency

|

||||||

|

work_latency = time.time() - start_time

|

||||||

|

...

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

考虑到上面的模式,我们经常使用修饰符、内容管理器、中间件(对于网络应用程序)所带来的好处去计算和报告指标。在 Demo 1 和 Demo 2 中,我们在一个 Flask 应用程序中使用修饰符。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 指标报告时的拉取和推送模型

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

大体来说,在一个 Python 应用程序中报告指标有两种模式。在 _拉取_ 模型中,监视系统在一个预定义的 HTTP 端点上“刮取”应用程序。在_推送_ 模型中,应用程序发送数据到监视系统。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

工作在 _拉取_ 模型中的监视系统的一个例子是 [Prometheus][12]。而 [StatsD][13] 是 _推送_ 模型的一个例子。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 集成 StatsD

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

将 StatsD 集成到一个 Python 应用程序中,我们将使用 [StatsD Python 客户端][14],然后更新我们的指标报告部分的代码,调用合适的库去推送数据到 StatsD 中。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

首先,我们需要去创建一个客户端实例:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

statsd = statsd.StatsClient(host='statsd', port=8125, prefix='webapp1')

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

`prefix` 关键字参数将为通过这个客户端报告的所有指标添加一个指定的前缀。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

一旦我们有了客户端,我们可以使用如下的代码为一个计时器报告值:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

statsd.timing(key, resp_time)

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

增加计数器:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

statsd.incr(key)

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

将指标关联到元数据上,一个键的定义为:metadata1.metadata2.metric,其中每个 metadataX 是一个可以进行聚合和分组的字段。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

这个演示应用程序 [StatsD][15] 是将 statsd 与 Python Flask 应用程序集成的一个完整示例。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 集成 Prometheus

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

去使用 Prometheus 监视系统,我们使用 [Promethius Python 客户端][16]。我们将首先去创建有关的指标类对象:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

REQUEST_LATENCY = Histogram('request_latency_seconds', 'Request latency',

|

||||||

|

['app_name', 'endpoint']

|

||||||

|

)

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

在上面的语句中的第三个参数是与这个指标相关的标识符。这些标识符是由与单个指标值相关联的元数据定义的。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

去记录一个特定的观测指标:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

REQUEST_LATENCY.labels('webapp', request.path).observe(resp_time)

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

下一步是在我们的应用程序中定义一个 Prometheus 能够刮取的 HTTP 端点。这通常是一个被称为 `/metrics` 的端点:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

@app.route('/metrics')

|

||||||

|

def metrics():

|

||||||

|

return Response(prometheus_client.generate_latest(), mimetype=CONTENT_TYPE_LATEST)

|

||||||

|

```

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

这个演示应用程序 [Prometheus][17] 是将 prometheus 与 Python Flask 应用程序集成的一个完整示例。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 哪个更好:StatsD 还是 Prometheus?

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

本能地想到的下一个问题便是:我应该使用 StatsD 还是 Prometheus?关于这个主题我写了几篇文章,你可能发现它们对你很有帮助:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

* [Your options for monitoring multi-process Python applications with Prometheus][18]

|

||||||

|

* [Monitoring your synchronous Python web applications using Prometheus][19]

|

||||||

|

* [Monitoring your asynchronous Python web applications using Prometheus][20]

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 指标的使用方式

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

我们已经学习了一些关于为什么要在我们的应用程序上配置监视的原因,而现在我们来更深入地研究其中的两个用法:报警和自动扩展。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 使用指标进行报警

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

指标的一个关键用途是创建警报。例如,假如过去的五分钟,你的 HTTP 500 的数量持续增加,你可能希望给相关的人发送一封电子邮件或页面提示。对于配置警报做什么取决于我们的监视设置。对于 Prometheus 我们可以使用 [Alertmanager][21],而对于 StatsD,我们使用 [Nagios][22]。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 使用指标进行自动扩展

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

在一个云基础设施中,如果我们当前的基础设施供应过量或供应不足,通过指标不仅可以让我们知道,还可以帮我们实现一个自动伸缩的策略。例如,如果在过去的五分钟里,在我们服务器上的工作进程使用率达到 90%,我们可以水平扩展。我们如何去扩展取决于云基础设施。AWS 的自动扩展,缺省情况下,扩展策略是基于系统的 CPU 使用率、网络流量、以及其它因素。然而,让基础设施伸缩的应用程序指标,我们必须发布 [自定义的 CloudWatch 指标][23]。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 在多服务架构中的应用程序监视

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

当我们超越一个单应用程序架构时,比如当客户端的请求在响应被发回之前,能够触发调用多个服务,就需要从我们的指标中获取更多的信息。我们需要一个统一的延迟视图指标,这样我们就能够知道响应这个请求时每个服务花费了多少时间。这可以用 [distributed tracing][24] 来实现。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

你可以在我的博客文章 [在你的 Python 应用程序中通过 Zipkin 引入分布式跟踪][25] 中看到在 Python 中进行分布式跟踪的示例。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 划重点

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

总之,你需要记住以下几点:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

* 理解你的监视系统中指标类型的含义

|

||||||

|

* 知道监视系统需要的你的数据的测量单位

|

||||||

|

* 监视你的应用程序中的大多数关键组件

|

||||||

|

* 监视你的应用程序在它的大多数关键阶段的行为

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

以上要点是假设你不去管理你的监视系统。如果管理你的监视系统是你的工作的一部分,那么你还要考虑更多的问题!

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 其它资源

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

以下是我在我的监视学习过程中找到的一些非常有用的资源:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### 综合的

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

* [监视分布式系统][26]

|

||||||

|

* [观测和监视最佳实践][27]

|

||||||

|

* [谁想使用秒?][28]

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### StatsD/Graphite

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

* [StatsD 指标类型][29]

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

### Prometheus

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

* [Prometheus 指标类型][30]

|

||||||

|

* [How does a Prometheus gauge work?][31]

|

||||||

|

* [Why are Prometheus histograms cumulative?][32]

|

||||||

|

* [在 Python 中监视批作业][33]

|

||||||

|

* [Prometheus:监视 SoundCloud][34]

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 避免犯错(即第 3 阶段的学习)

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

在我们学习监视的基本知识时,时刻注意不要犯错误是很重要的。以下是我偶然发现的一些很有见解的资源:

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

* [How not to measure latency][35]

|

||||||

|

* [Histograms with Prometheus: A tale of woe][36]

|

||||||

|

* [Why averages suck and percentiles are great][37]

|

||||||

|

* [Everything you know about latency is wrong][38]

|

||||||

|

* [Who moved my 99th percentile latency?][39]

|

||||||

|

* [Logs and metrics and graphs][40]

|

||||||

|

* [HdrHistogram: A better latency capture method][41]

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

---

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

想学习更多内容,参与到 [PyCon Cleveland 2018][43] 上的 Amit Saha 的讨论,[Counter, gauge, upper 90—Oh my!][42]

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

## 关于作者

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[][44]

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

Amit Saha — 我是一名对基础设施、监视、和工具感兴趣的软件工程师。我是“用 Python 做数学”的作者和创始人,以及 Fedora Scientific Spin 维护者。

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[关于我的更多信息][45]

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

* [Learn how you can contribute][46]

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

---

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

via: [https://opensource.com/article/18/4/metrics-monitoring-and-python][47]

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

作者: [Amit Saha][48] 选题者: [@lujun9972][49] 译者: [qhwdw][50] 校对: [校对者ID][51]

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

本文由 [LCTT][52] 原创编译,[Linux中国][53] 荣誉推出

|

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

[1]: https://opensource.com/resources/python?intcmp=7016000000127cYAAQ

|

||||||

|

[2]: https://opensource.com/resources/python/ides?intcmp=7016000000127cYAAQ

|

||||||

|

[3]: https://opensource.com/resources/python/gui-frameworks?intcmp=7016000000127cYAAQ

|

||||||

|

[4]: https://opensource.com/tags/python?intcmp=7016000000127cYAAQ

|

||||||

|

[5]: https://developers.redhat.com/?intcmp=7016000000127cYAAQ

|

||||||

|

[6]: https://github.com/amitsaha/python-monitoring-talk

|

||||||

|

[7]: https://github.com/amitsaha/python-monitoring-talk/tree/master/demo1

|

||||||

|

[8]: http://flask.pocoo.org/

|

||||||

|

[9]: https://github.com/amitsaha/python-monitoring-talk/tree/master/demo2

|

||||||

|

[10]: https://pandas.pydata.org/

|

||||||

|

[11]: http://jupyter.org/

|

||||||

|

[12]: https://prometheus.io/

|

||||||

|

[13]: https://github.com/etsy/statsd

|

||||||

|

[14]: https://pypi.python.org/pypi/statsd

|

||||||

|

[15]: https://github.com/amitsaha/python-monitoring-talk/tree/master/statsd

|

||||||

|

[16]: https://pypi.python.org/pypi/prometheus_client

|

||||||

|

[17]: https://github.com/amitsaha/python-monitoring-talk/tree/master/prometheus

|

||||||

|

[18]: http://echorand.me/your-options-for-monitoring-multi-process-python-applications-with-prometheus.html

|

||||||

|

[19]: https://blog.codeship.com/monitoring-your-synchronous-python-web-applications-using-prometheus/

|

||||||

|

[20]: https://blog.codeship.com/monitoring-your-asynchronous-python-web-applications-using-prometheus/

|

||||||

|

[21]: https://github.com/prometheus/alertmanager

|

||||||

|

[22]: https://www.nagios.org/about/overview/

|

||||||

|

[23]: https://docs.aws.amazon.com/AmazonCloudWatch/latest/monitoring/publishingMetrics.html

|

||||||

|

[24]: http://opentracing.io/documentation/

|

||||||

|

[25]: http://echorand.me/introducing-distributed-tracing-in-your-python-application-via-zipkin.html

|

||||||

|

[26]: https://landing.google.com/sre/book/chapters/monitoring-distributed-systems.html

|

||||||

|

[27]: http://www.integralist.co.uk/posts/monitoring-best-practices/?imm_mid=0fbebf&cmp=em-webops-na-na-newsltr_20180309

|

||||||

|

[28]: https://www.robustperception.io/who-wants-seconds/

|

||||||

|

[29]: https://github.com/etsy/statsd/blob/master/docs/metric_types.md

|

||||||

|

[30]: https://prometheus.io/docs/concepts/metric_types/

|

||||||

|

[31]: https://www.robustperception.io/how-does-a-prometheus-gauge-work/

|

||||||

|

[32]: https://www.robustperception.io/why-are-prometheus-histograms-cumulative/

|

||||||

|

[33]: https://www.robustperception.io/monitoring-batch-jobs-in-python/

|

||||||

|

[34]: https://developers.soundcloud.com/blog/prometheus-monitoring-at-soundcloud

|

||||||

|

[35]: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lJ8ydIuPFeU&feature=youtu.be

|

||||||

|

[36]: http://linuxczar.net/blog/2017/06/15/prometheus-histogram-2/

|

||||||

|

[37]: https://www.dynatrace.com/news/blog/why-averages-suck-and-percentiles-are-great/

|

||||||

|

[38]: https://bravenewgeek.com/everything-you-know-about-latency-is-wrong/

|

||||||

|

[39]: https://engineering.linkedin.com/performance/who-moved-my-99th-percentile-latency

|

||||||

|

[40]: https://grafana.com/blog/2016/01/05/logs-and-metrics-and-graphs-oh-my/

|

||||||

|

[41]: http://psy-lob-saw.blogspot.com.au/2015/02/hdrhistogram-better-latency-capture.html

|

||||||

|

[42]: https://us.pycon.org/2018/schedule/presentation/133/

|

||||||

|

[43]: https://us.pycon.org/2018/

|

||||||

|

[44]: https://opensource.com/users/amitsaha

|

||||||

|

[45]: https://opensource.com/users/amitsaha

|

||||||

|

[46]: https://opensource.com/participate

|

||||||

|

[47]: https://opensource.com/article/18/4/metrics-monitoring-and-python

|

||||||

|

[48]: https://opensource.com/users/amitsaha

|

||||||

|

[49]: https://github.com/lujun9972

|

||||||

|

[50]: https://github.com/qhwdw

|

||||||

|

[51]: https://github.com/校对者ID

|

||||||

|

[52]: https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject

|

||||||

|

[53]: https://linux.cn/

|

||||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user