mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-01-13 22:30:37 +08:00

Translated by qhwdw

This commit is contained in:

parent

6f19905558

commit

3b8c56a260

@ -1,152 +0,0 @@

|

||||

translating by qhwdw Notes on BPF & eBPF

|

||||

============================================================

|

||||

|

||||

Today it was Papers We Love, my favorite meetup! Today [Suchakra Sharma][6]([@tuxology][7] on twitter/github) gave a GREAT talk about the original BPF paper and recent work in Linux on eBPF. It really made me want to go write eBPF programs!

|

||||

|

||||

The paper is [The BSD Packet Filter: A New Architecture for User-level Packet Capture][8]

|

||||

|

||||

I wanted to write some notes on the talk here because I thought it was super super good.

|

||||

|

||||

To start, here are the [slides][9] and a [pdf][10]. The pdf is good because there are links at the end and in the PDF you can click the links.

|

||||

|

||||

### what’s BPF?

|

||||

|

||||

Before BPF, if you wanted to do packet filtering you had to copy all the packets into userspace and then filter them there (with “tap”).

|

||||

|

||||

this had 2 problems:

|

||||

|

||||

1. if you filter in userspace, it means you have to copy all the packets into userspace, copying data is expensive

|

||||

|

||||

2. the filtering algorithms people were using were inefficient

|

||||

|

||||

The solution to problem #1 seems sort of obvious, move the filtering logic into the kernel somehow. Okay. (though the details of how that’s done isn’t obvious, we’ll talk about that in a second)

|

||||

|

||||

But why were the filtering algorithms inefficient! Well!!

|

||||

|

||||

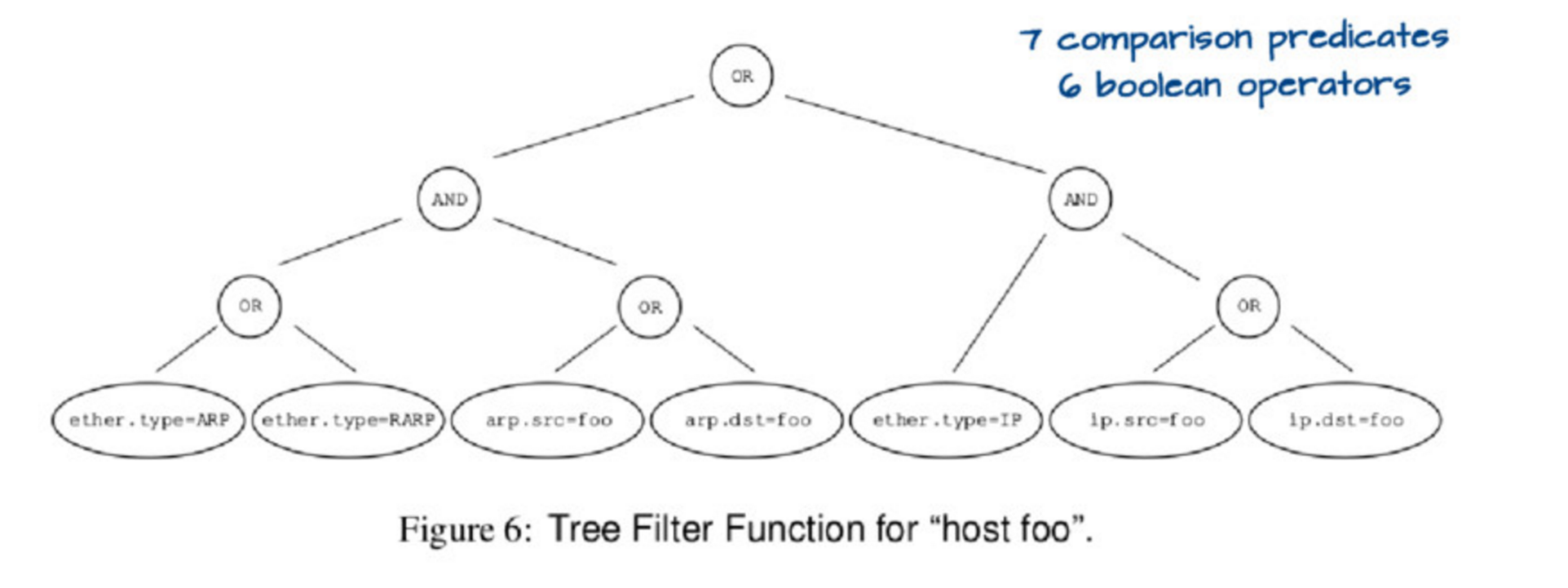

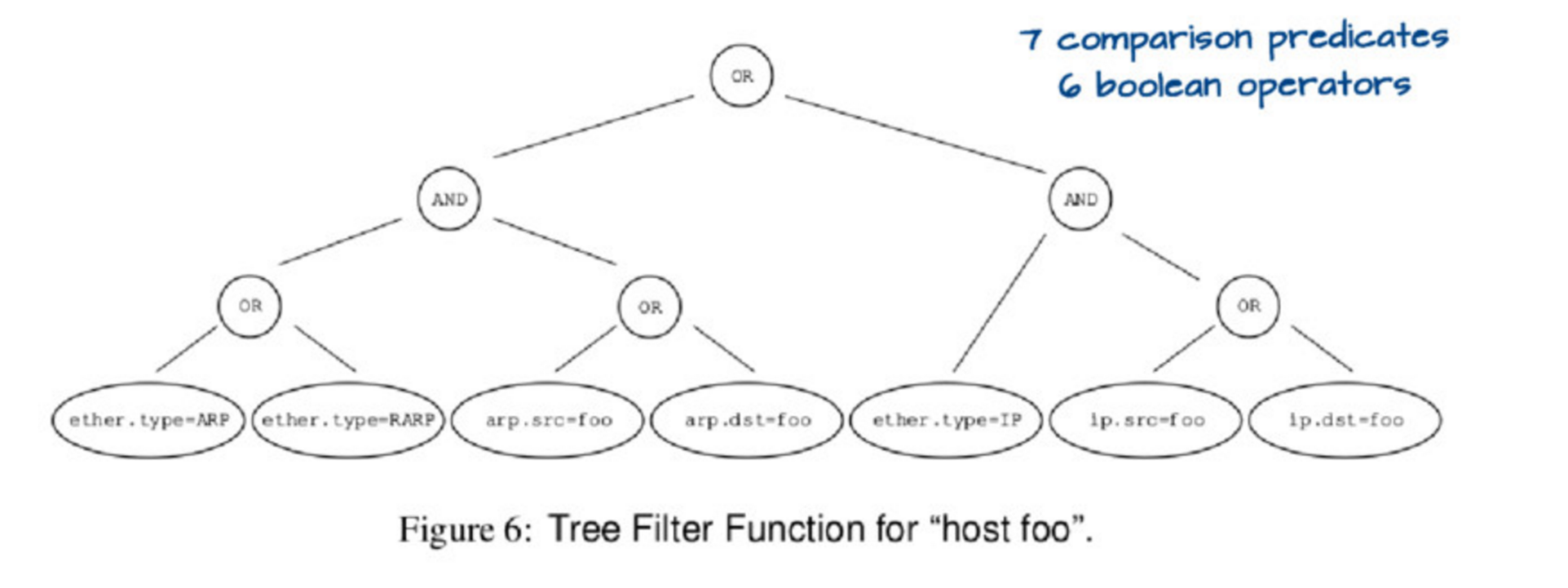

If you run `tcpdump host foo` it actually runs a relatively complicated query, which you could represent with this tree:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

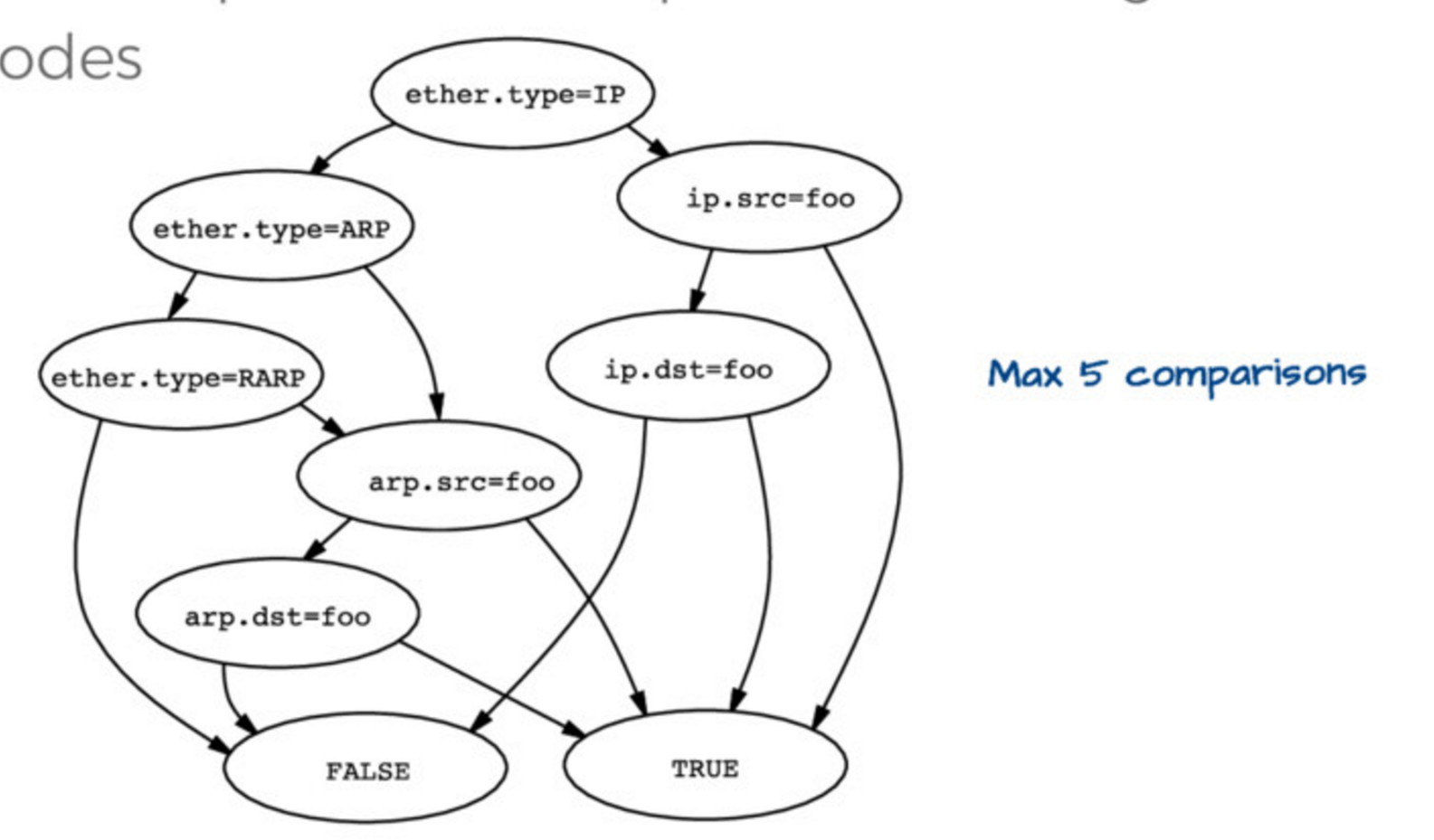

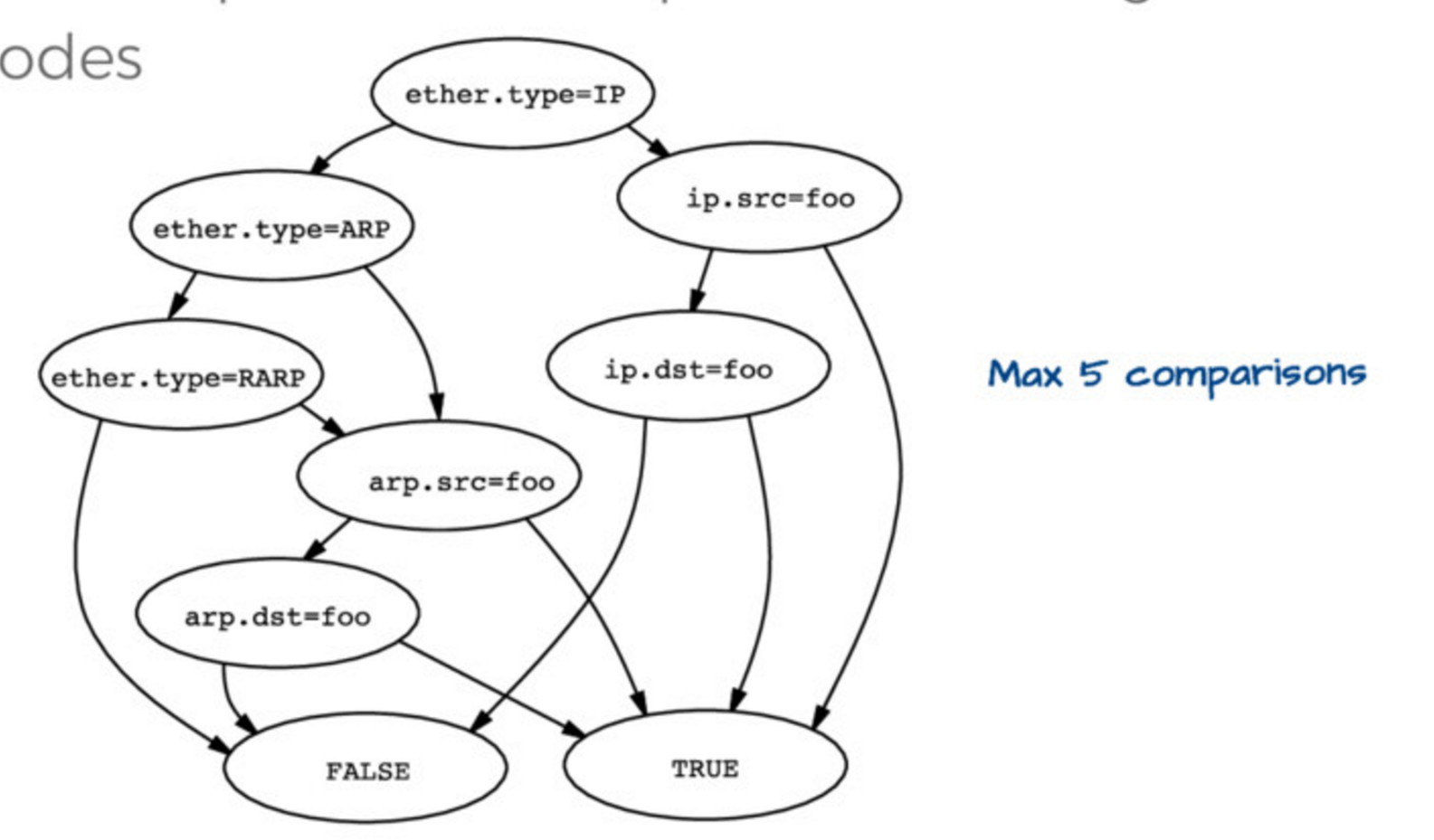

Evaluating this tree is kind of expensive. so the first insight is that you can actually represent this tree in a simpler way, like this:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Then if you have `ether.type = IP` and `ip.src = foo` you automatically know that the packet matches `host foo`, you don’t need to check anything else. So this data structure (they call it a “control flow graph” or “CFG”) is a way better representation of the program you actually want to execute to check matches than the tree we started with.

|

||||

|

||||

### How BPF works in the kernel

|

||||

|

||||

The main important here is that packets are just arrays of bytes. BPF programs run on these arrays of bytes. They’re not allowed to have loops but they _can_ have smart stuff to figure out the length of the IP header (IPv6 & IPv4 are different lengths!) and then find the TCP port based on that length

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

x = ip_header_length

|

||||

port = *(packet_start + x + port_offset)

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

(it looks different from that but it’s basically the same). There’s a nice description of the virtual machine in the paper/slides so I won’t explain it.

|

||||

|

||||

When you run `tcpdump host foo` this is what happens, as far as I understand

|

||||

|

||||

1. convert `host foo` into an efficient DAG of the rules

|

||||

|

||||

2. convert that DAG into a BPF program (in BPF bytecode) for the BPF virtual machine

|

||||

|

||||

3. Send the BPF bytecode to the Linux kernel, which verifies it

|

||||

|

||||

4. compile the BPF bytecode program into native code. For example [here’s the JIT code for ARM][1] and for [x86][2]

|

||||

|

||||

5. when packets come in, Linux runs the native code to decide if that packet should be filtered or not. It’l often run only 100-200 CPU instructions for each packet that needs to be processed, which is super fast!

|

||||

|

||||

### the present: eBPF

|

||||

|

||||

But BPF has been around for a long time! Now we live in the EXCITING FUTURE which is eBPF. I’d heard about eBPF a bunch before but I felt like this helped me put the pieces together a little better. (i wrote this [XDP & eBPF post][11]back in April when I was at netdev)

|

||||

|

||||

some facts about eBPF:

|

||||

|

||||

* eBPF programs have their own bytecode language, and are compiled from that bytecode language into native code in the kernel, just like BPF programs

|

||||

|

||||

* eBPF programs run in the kernel

|

||||

|

||||

* eBPF programs can’t access arbitrary kernel memory. Instead the kernel provides functions to get at some restricted subset of things.

|

||||

|

||||

* they _can_ communicate with userspace programs through BPF maps

|

||||

|

||||

* there’s a `bpf` syscall as of Linux 3.18

|

||||

|

||||

### kprobes & eBPF

|

||||

|

||||

You can pick a function (any function!) in the Linux kernel and execute a program that you write every time that function happens. This seems really amazing and magical.

|

||||

|

||||

For example! There’s this [BPF program called disksnoop][12] which tracks when you start/finish writing a block to disk. Here’s a snippet from the code:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

BPF_HASH(start, struct request *);

|

||||

void trace_start(struct pt_regs *ctx, struct request *req) {

|

||||

// stash start timestamp by request ptr

|

||||

u64 ts = bpf_ktime_get_ns();

|

||||

start.update(&req, &ts);

|

||||

}

|

||||

...

|

||||

b.attach_kprobe(event="blk_start_request", fn_name="trace_start")

|

||||

b.attach_kprobe(event="blk_mq_start_request", fn_name="trace_start")

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

This basically declares a BPF hash (which the program uses to keep track of when the request starts / finishes), a function called `trace_start` which is going to be compiled into BPF bytecode, and attaches `trace_start` to the `blk_start_request` kernel function.

|

||||

|

||||

This is all using the `bcc` framework which lets you write Python-ish programs that generate BPF code. You can find it (it has tons of example programs) at[https://github.com/iovisor/bcc][13]

|

||||

|

||||

### uprobes & eBPF

|

||||

|

||||

So I sort of knew you could attach eBPF programs to kernel functions, but I didn’t realize you could attach eBPF programs to userspace functions! That’s really exciting. Here’s [an example of counting malloc calls in Python using an eBPF program][14].

|

||||

|

||||

### things you can attach eBPF programs to

|

||||

|

||||

* network cards, with XDP (which I wrote about a while back)

|

||||

|

||||

* tc egress/ingress (in the network stack)

|

||||

|

||||

* kprobes (any kernel function)

|

||||

|

||||

* uprobes (any userspace function apparently ?? like in any C program with symbols.)

|

||||

|

||||

* probes that were built for dtrace called “USDT probes” (like [these mysql probes][3]). Here’s an [example program using dtrace probes][4]

|

||||

|

||||

* [the JVM][5]

|

||||

|

||||

* tracepoints (not sure what that is yet)

|

||||

|

||||

* seccomp / landlock security things

|

||||

|

||||

* a bunch more things

|

||||

|

||||

### this talk was super cool

|

||||

|

||||

There are a bunch of great links in the slides and in [LINKS.md][15] in the iovisor repository. It is late now but soon I want to actually write my first eBPF program!

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://jvns.ca/blog/2017/06/28/notes-on-bpf---ebpf/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Julia Evans ][a]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:https://jvns.ca/

|

||||

[1]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v4.10/arch/arm/net/bpf_jit_32.c#L512

|

||||

[2]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.18/arch/x86/net/bpf_jit_comp.c#L189

|

||||

[3]:https://dev.mysql.com/doc/refman/5.7/en/dba-dtrace-ref-query.html

|

||||

[4]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/examples/tracing/mysqld_query.py

|

||||

[5]:http://blogs.microsoft.co.il/sasha/2016/03/31/probing-the-jvm-with-bpfbcc/

|

||||

[6]:http://suchakra.in/

|

||||

[7]:https://twitter.com/tuxology

|

||||

[8]:http://www.vodun.org/papers/net-papers/van_jacobson_the_bpf_packet_filter.pdf

|

||||

[9]:https://speakerdeck.com/tuxology/the-bsd-packet-filter

|

||||

[10]:http://step.polymtl.ca/~suchakra/PWL-Jun28-MTL.pdf

|

||||

[11]:https://jvns.ca/blog/2017/04/07/xdp-bpf-tutorial/

|

||||

[12]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/0c8c179fc1283600887efa46fe428022efc4151b/examples/tracing/disksnoop.py

|

||||

[13]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc

|

||||

[14]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/00f662dbea87a071714913e5c7382687fef6a508/tests/lua/test_uprobes.lua

|

||||

[15]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/LINKS.md

|

||||

152

translated/tech/20170628 Notes on BPF and eBPF.md

Normal file

152

translated/tech/20170628 Notes on BPF and eBPF.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,152 @@

|

||||

关于 BPF 和 eBPF 的笔记

|

||||

============================================================

|

||||

|

||||

今天,我喜欢的 meetup 网站上有一篇我超爱的文章![Suchakra Sharma][6]([@tuxology][7] 在 twitter/github)的一篇非常棒的关于传统 BPF 和在 Linux 中最新加入的 eBPF 的讨论文章,正是它促使我想去写一个 eBPF 的程序!

|

||||

|

||||

这篇文章就是 —— [BSD 包过滤器:一个新的用户级包捕获架构][8]

|

||||

|

||||

我想在讨论的基础上去写一些笔记,因为,我觉得它超级棒!

|

||||

|

||||

这是 [幻灯片][9] 和一个 [pdf][10]。这个 pdf 非常好,结束的位置有一些链接,在 PDF 中你可以直接点击这个链接。

|

||||

|

||||

### 什么是 BPF?

|

||||

|

||||

在 BPF 出现之前,如果你想去做包过滤,你必须拷贝所有进入用户空间的包,然后才能去过滤它们(使用 “tap”)。

|

||||

|

||||

这样做存在两个问题:

|

||||

|

||||

1. 如果你在用户空间中过滤,意味着你将拷贝所有进入用户空间的包,拷贝数据的代价是很昂贵的。

|

||||

|

||||

2. 使用的过滤算法很低效

|

||||

|

||||

问题 #1 的解决方法似乎很明显,就是将过滤逻辑移到内核中。(虽然具体实现的细节并没有明确,我们将在稍后讨论)

|

||||

|

||||

但是,为什么过滤算法会很低效?

|

||||

|

||||

如果你运行 `tcpdump host foo`,它实际上运行了一个相当复杂的查询,用下图的这个树来描述它:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

评估这个树有点复杂。因此,可以用一种更简单的方式来表示这个树,像这样:

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

然后,如果你设置 `ether.type = IP` 和 `ip.src = foo`,你必然明白匹配的包是 `host foo`,你也不用去检查任何其它的东西了。因此,这个数据结构(它们称为“控制流图” ,或者 “CFG”)是表示你真实希望去执行匹配检查的程序的最佳方法,而不是用前面的树。

|

||||

|

||||

### 为什么 BPF 要工作在内核中

|

||||

|

||||

这里的关键点是,包仅仅是个字节的数组。BPF 程序是运行在这些字节的数组上。它们不允许有循环(loops),但是,它们 _可以_ 有聪明的办法知道 IP 包头(IPv6 和 IPv4 长度是不同的)以及基于它们的长度来找到 TCP 端口

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

x = ip_header_length

|

||||

port = *(packet_start + x + port_offset)

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

(看起来不一样,其实它们基本上都相同)。在这个论文/幻灯片上有一个非常详细的虚拟机的描述,因此,我不打算解释它。

|

||||

|

||||

当你运行 `tcpdump host foo` 后,这时发生了什么?就我的理解,应该是如下的过程。

|

||||

|

||||

1. 转换 `host foo` 为一个高效的 DAG 规则

|

||||

|

||||

2. 转换那个 DAG 规则为 BPF 虚拟机的一个 BPF 程序(BPF 字节码)

|

||||

|

||||

3. 发送 BPF 字节码到 Linux 内核,由 Linux 内核验证它

|

||||

|

||||

4. 编译这个 BPF 字节码程序为一个原生(native)代码。例如, [在 ARM 上是 JIT 代码][1] 以及为 [x86][2] 的机器码

|

||||

|

||||

5. 当包进入时,Linux 运行原生代码去决定是否过滤这个包。对于每个需要去处理的包,它通常仅需运行 100 - 200 个 CPU 指令就可以完成,这个速度是非常快的!

|

||||

|

||||

### 现状:eBPF

|

||||

|

||||

毕竟 BPF 出现已经有很长的时间了!现在,我们可以拥有一个更加令人激动的东西,它就是 eBPF。我以前听说过 eBPF,但是,我觉得像这样把这些片断拼在一起更好(我在 4 月份的 netdev 上我写了这篇 [XDP & eBPF 的文章][11]回复)

|

||||

|

||||

关于 eBPF 的一些事实是:

|

||||

|

||||

* eBPF 程序有它们自己的字节码语言,并且从那个字节码语言编译成内核原生代码,就像 BPF 程序

|

||||

|

||||

* eBPF 运行在内核中

|

||||

|

||||

* eBPF 程序不能随心所欲的访问内核内存。而是通过内核提供的函数去取得一些受严格限制的所需要的内容的子集。

|

||||

|

||||

* 它们 _可以_ 与用户空间的程序通过 BPF 映射进行通讯

|

||||

|

||||

* 这是 Linux 3.18 的 `bpf` 系统调用

|

||||

|

||||

### kprobes 和 eBPF

|

||||

|

||||

你可以在 Linux 内核中挑选一个函数(任意函数),然后运行一个你写的每次函数被调用时都运行的程序。这样看起来是不是很神奇。

|

||||

|

||||

例如:这里有一个 [名为 disksnoop 的 BPF 程序][12],它的功能是当你开始/完成写入一个块到磁盘时,触发它执行跟踪。下图是它的代码片断:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

BPF_HASH(start, struct request *);

|

||||

void trace_start(struct pt_regs *ctx, struct request *req) {

|

||||

// stash start timestamp by request ptr

|

||||

u64 ts = bpf_ktime_get_ns();

|

||||

start.update(&req, &ts);

|

||||

}

|

||||

...

|

||||

b.attach_kprobe(event="blk_start_request", fn_name="trace_start")

|

||||

b.attach_kprobe(event="blk_mq_start_request", fn_name="trace_start")

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

从根本上来说,它声明一个 BPF 哈希(它的作用是当请求开始/完成时,这个程序去触发跟踪),一个名为 `trace_start` 的函数将被编译进 BPF 字节码,然后附加 `trace_start` 到内核函数 `blk_start_request` 上。

|

||||

|

||||

这里使用的是 `bcc` 框架,它可以使你写的 Python 化的程序去生成 BPF 代码。你可以在 [https://github.com/iovisor/bcc][13] 找到它(那里有非常多的示例程序)。

|

||||

|

||||

### uprobes 和 eBPF

|

||||

|

||||

因为我知道你可以附加 eBPF 程序到内核函数上,但是,我不知道你能否将 eBPF 程序附加到用户空间函数上!那会有更多令人激动的事情。这是 [在 Python 中使用一个 eBPF 程序去计数 malloc 调用的示例][14]。

|

||||

|

||||

### 附加 eBPF 程序时应该考虑的事情

|

||||

|

||||

* 带 XDP 的网卡(我之前写过关于这方面的文章)

|

||||

|

||||

* tc egress/ingress (在网络栈上)

|

||||

|

||||

* kprobes(任意内核函数)

|

||||

|

||||

* uprobes(很明显,任意用户空间函数??像带符号的任意 C 程序)

|

||||

|

||||

* probes 是为 dtrace 构建的名为 “USDT probes” 的探针(像 [这些 mysql 探针][3])。这是一个 [使用 dtrace 探针的示例程序][4]

|

||||

|

||||

* [JVM][5]

|

||||

|

||||

* 跟踪点

|

||||

|

||||

* seccomp / landlock 安全相关的事情

|

||||

|

||||

* 更多的事情

|

||||

|

||||

### 这个讨论超级棒

|

||||

|

||||

在幻灯片里有很多非常好的链接,并且在 iovisor 仓库里有个 [LINKS.md][15]。现在已经很晚了,但是,很快我将写我的第一个 eBPF 程序了!

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://jvns.ca/blog/2017/06/28/notes-on-bpf---ebpf/

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Julia Evans ][a]

|

||||

译者:[qhwdw](https://github.com/qhwdw)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:https://jvns.ca/

|

||||

[1]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v4.10/arch/arm/net/bpf_jit_32.c#L512

|

||||

[2]:https://github.com/torvalds/linux/blob/v3.18/arch/x86/net/bpf_jit_comp.c#L189

|

||||

[3]:https://dev.mysql.com/doc/refman/5.7/en/dba-dtrace-ref-query.html

|

||||

[4]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/examples/tracing/mysqld_query.py

|

||||

[5]:http://blogs.microsoft.co.il/sasha/2016/03/31/probing-the-jvm-with-bpfbcc/

|

||||

[6]:http://suchakra.in/

|

||||

[7]:https://twitter.com/tuxology

|

||||

[8]:http://www.vodun.org/papers/net-papers/van_jacobson_the_bpf_packet_filter.pdf

|

||||

[9]:https://speakerdeck.com/tuxology/the-bsd-packet-filter

|

||||

[10]:http://step.polymtl.ca/~suchakra/PWL-Jun28-MTL.pdf

|

||||

[11]:https://jvns.ca/blog/2017/04/07/xdp-bpf-tutorial/

|

||||

[12]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/0c8c179fc1283600887efa46fe428022efc4151b/examples/tracing/disksnoop.py

|

||||

[13]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc

|

||||

[14]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/00f662dbea87a071714913e5c7382687fef6a508/tests/lua/test_uprobes.lua

|

||||

[15]:https://github.com/iovisor/bcc/blob/master/LINKS.md

|

||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user