mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-03-27 02:30:10 +08:00

translated by cycoe

This commit is contained in:

parent

f039536907

commit

2759846ed3

@ -1,164 +0,0 @@

|

||||

Translating by Cycoe

|

||||

Cycoe 翻译中

|

||||

[#]: collector: (lujun9972)

|

||||

[#]: translator: ( )

|

||||

[#]: reviewer: ( )

|

||||

[#]: publisher: ( )

|

||||

[#]: url: ( )

|

||||

[#]: subject: (How to add a player to your Python game)

|

||||

[#]: via: (https://opensource.com/article/17/12/game-python-add-a-player)

|

||||

[#]: author: (Seth Kenlon https://opensource.com/users/seth)

|

||||

|

||||

How to add a player to your Python game

|

||||

======

|

||||

Part three of a series on building a game from scratch with Python.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

In the [first article of this series][1], I explained how to use Python to create a simple, text-based dice game. In the second part, I showed you how to build a game from scratch, starting with [creating the game's environment][2]. But every game needs a player, and every player needs a playable character, so that's what we'll do next in the third part of the series.

|

||||

|

||||

In Pygame, the icon or avatar that a player controls is called a sprite. If you don't have any graphics to use for a player sprite yet, create something for yourself using [Krita][3] or [Inkscape][4]. If you lack confidence in your artistic skills, you can also search [OpenClipArt.org][5] or [OpenGameArt.org][6] for something pre-generated. Then, if you didn't already do so in the previous article, create a directory called `images` alongside your Python project directory. Put the images you want to use in your game into the `images` folder.

|

||||

|

||||

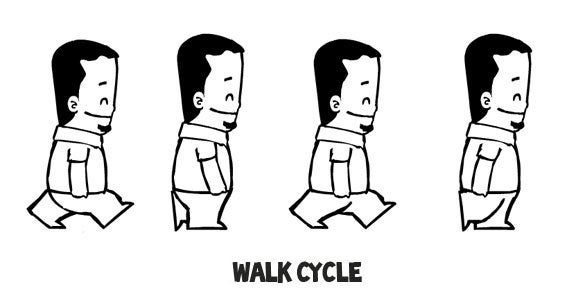

To make your game truly exciting, you ought to use an animated sprite for your hero. It means you have to draw more assets, but it makes a big difference. The most common animation is a walk cycle, a series of drawings that make it look like your sprite is walking. The quick and dirty version of a walk cycle requires four drawings.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Note: The code samples in this article allow for both a static player sprite and an animated one.

|

||||

|

||||

Name your player sprite `hero.png`. If you're creating an animated sprite, append a digit after the name, starting with `hero1.png`.

|

||||

|

||||

### Create a Python class

|

||||

|

||||

In Python, when you create an object that you want to appear on screen, you create a class.

|

||||

|

||||

Near the top of your Python script, add the code to create a player. In the code sample below, the first three lines are already in the Python script that you're working on:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

import pygame

|

||||

import sys

|

||||

import os # new code below

|

||||

|

||||

class Player(pygame.sprite.Sprite):

|

||||

'''

|

||||

Spawn a player

|

||||

'''

|

||||

def __init__(self):

|

||||

pygame.sprite.Sprite.__init__(self)

|

||||

self.images = []

|

||||

img = pygame.image.load(os.path.join('images','hero.png')).convert()

|

||||

self.images.append(img)

|

||||

self.image = self.images[0]

|

||||

self.rect = self.image.get_rect()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

If you have a walk cycle for your playable character, save each drawing as an individual file called `hero1.png` to `hero4.png` in the `images` folder.

|

||||

|

||||

Use a loop to tell Python to cycle through each file.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

'''

|

||||

Objects

|

||||

'''

|

||||

|

||||

class Player(pygame.sprite.Sprite):

|

||||

'''

|

||||

Spawn a player

|

||||

'''

|

||||

def __init__(self):

|

||||

pygame.sprite.Sprite.__init__(self)

|

||||

self.images = []

|

||||

for i in range(1,5):

|

||||

img = pygame.image.load(os.path.join('images','hero' + str(i) + '.png')).convert()

|

||||

self.images.append(img)

|

||||

self.image = self.images[0]

|

||||

self.rect = self.image.get_rect()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

### Bring the player into the game world

|

||||

|

||||

Now that a Player class exists, you must use it to spawn a player sprite in your game world. If you never call on the Player class, it never runs, and there will be no player. You can test this out by running your game now. The game will run just as well as it did at the end of the previous article, with the exact same results: an empty game world.

|

||||

|

||||

To bring a player sprite into your world, you must call the Player class to generate a sprite and then add it to a Pygame sprite group. In this code sample, the first three lines are existing code, so add the lines afterwards:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

world = pygame.display.set_mode([worldx,worldy])

|

||||

backdrop = pygame.image.load(os.path.join('images','stage.png')).convert()

|

||||

backdropbox = screen.get_rect()

|

||||

|

||||

# new code below

|

||||

|

||||

player = Player() # spawn player

|

||||

player.rect.x = 0 # go to x

|

||||

player.rect.y = 0 # go to y

|

||||

player_list = pygame.sprite.Group()

|

||||

player_list.add(player)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Try launching your game to see what happens. Warning: it won't do what you expect. When you launch your project, the player sprite doesn't spawn. Actually, it spawns, but only for a millisecond. How do you fix something that only happens for a millisecond? You might recall from the previous article that you need to add something to the main loop. To make the player spawn for longer than a millisecond, tell Python to draw it once per loop.

|

||||

|

||||

Change the bottom clause of your loop to look like this:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

world.blit(backdrop, backdropbox)

|

||||

player_list.draw(screen) # draw player

|

||||

pygame.display.flip()

|

||||

clock.tick(fps)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Launch your game now. Your player spawns!

|

||||

|

||||

### Setting the alpha channel

|

||||

|

||||

Depending on how you created your player sprite, it may have a colored block around it. What you are seeing is the space that ought to be occupied by an alpha channel. It's meant to be the "color" of invisibility, but Python doesn't know to make it invisible yet. What you are seeing, then, is the space within the bounding box (or "hit box," in modern gaming terms) around the sprite.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

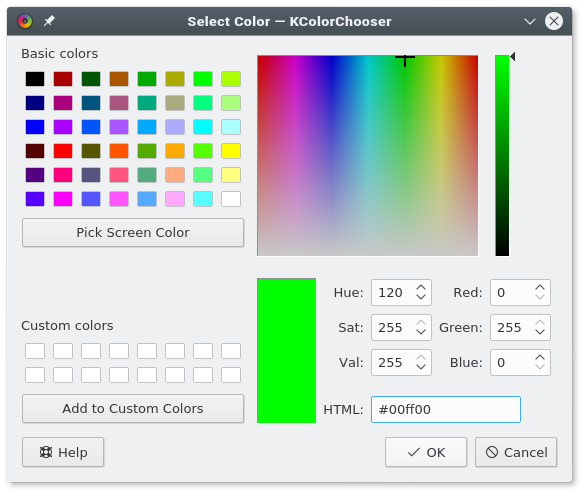

You can tell Python what color to make invisible by setting an alpha channel and using RGB values. If you don't know the RGB values your drawing uses as alpha, open your drawing in Krita or Inkscape and fill the empty space around your drawing with a unique color, like #00ff00 (more or less a "greenscreen green"). Take note of the color's hex value (#00ff00, for greenscreen green) and use that in your Python script as the alpha channel.

|

||||

|

||||

Using alpha requires the addition of two lines in your Sprite creation code. Some version of the first line is already in your code. Add the other two lines:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

img = pygame.image.load(os.path.join('images','hero' + str(i) + '.png')).convert()

|

||||

img.convert_alpha() # optimise alpha

|

||||

img.set_colorkey(ALPHA) # set alpha

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Python doesn't know what to use as alpha unless you tell it. In the setup area of your code, add some more color definitions. Add this variable definition anywhere in your setup section:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

ALPHA = (0, 255, 0)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

In this example code, **0,255,0** is used, which is the same value in RGB as #00ff00 is in hex. You can get all of these color values from a good graphics application like [GIMP][7], Krita, or Inkscape. Alternately, you can also detect color values with a good system-wide color chooser, like [KColorChooser][8].

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

If your graphics application is rendering your sprite's background as some other value, adjust the values of your alpha variable as needed. No matter what you set your alpha value, it will be made "invisible." RGB values are very strict, so if you need to use 000 for alpha, but you need 000 for the black lines of your drawing, just change the lines of your drawing to 111, which is close enough to black that nobody but a computer can tell the difference.

|

||||

|

||||

Launch your game to see the results.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

In the [fourth part of this series][9], I'll show you how to make your sprite move. How exciting!

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://opensource.com/article/17/12/game-python-add-a-player

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Seth Kenlon][a]

|

||||

选题:[lujun9972][b]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]: https://opensource.com/users/seth

|

||||

[b]: https://github.com/lujun9972

|

||||

[1]: https://opensource.com/article/17/10/python-101

|

||||

[2]: https://opensource.com/article/17/12/program-game-python-part-2-creating-game-world

|

||||

[3]: http://krita.org

|

||||

[4]: http://inkscape.org

|

||||

[5]: http://openclipart.org

|

||||

[6]: https://opengameart.org/

|

||||

[7]: http://gimp.org

|

||||

[8]: https://github.com/KDE/kcolorchooser

|

||||

[9]: https://opensource.com/article/17/12/program-game-python-part-4-moving-your-sprite

|

||||

@ -0,0 +1,162 @@

|

||||

[#]: collector: (lujun9972)

|

||||

[#]: translator: ( )

|

||||

[#]: reviewer: ( )

|

||||

[#]: publisher: ( )

|

||||

[#]: url: ( )

|

||||

[#]: subject: (How to add a player to your Python game)

|

||||

[#]: via: (https://opensource.com/article/17/12/game-python-add-a-player)

|

||||

[#]: author: (Seth Kenlon https://opensource.com/users/seth)

|

||||

|

||||

如何在你的 Python 游戏中添加一个玩家

|

||||

======

|

||||

用 Python 从头开始构建游戏的系列文章的第三部分。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

在 [这个系列的第一篇文章][1] 中,我解释了如何使用 Python 创建一个简单的基于文本的骰子游戏。在第二部分中,我向你们展示了如何从头开始构建游戏,即从 [创建游戏的环境][2] 开始。但是每个游戏都需要一名玩家,并且每个玩家都需要一个可操控的角色,这也就是我们接下来要在这个系列的第三部分中需要做的。

|

||||

|

||||

在 Pygame 中,玩家操控的图标或者化身被称作妖精。如果你现在还没有任何图像可用于玩家妖精,你可以使用 [Krita][3] 或 [Inkscape][4] 来自己创建一些图像。如果你对自己的艺术细胞缺乏自信,你也可以在 [OpenClipArt.org][5] 或 [OpenGameArt.org][6] 搜索一些现成的图像。如果你还未按照上一篇文章所说的单独创建一个 images 文件夹,那么你需要在你的 Python 项目目录中创建它。将你想要在游戏中使用的图片都放 images 文件夹中。

|

||||

|

||||

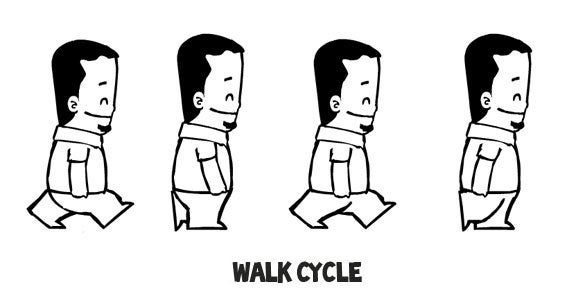

为了使你的游戏真正的刺激,你应该为你的英雄使用一张动态的妖精图片。这意味着你需要绘制更多的素材,并且它们要大不相同。最常见的动画就是走路循环,通过一系列的图像让你的妖精看起来像是在走路。走路循环最快捷粗糙的版本需要四张图像。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

注意:这篇文章中的代码示例同时兼容静止的和动态的玩家妖精。

|

||||

|

||||

将你的玩家妖精命名为 `hero.png`。如果你正在创建一个动态的妖精,则需要在名字后面加上一个数字,从 `hero1.png` 开始。

|

||||

|

||||

### 创建一个 Python 类

|

||||

|

||||

在 Python 中,当你在创建一个你想要显示在屏幕上的对象时,你需要创建一个类。

|

||||

|

||||

在你的 Python 脚本靠近顶端的位置,加入如下代码来创建一个玩家。在以下的代码示例中,前三行已经在你正在处理的 Python 脚本中:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

import pygame

|

||||

import sys

|

||||

import os # 以下是新代码

|

||||

|

||||

class Player(pygame.sprite.Sprite):

|

||||

'''

|

||||

生成一个玩家

|

||||

'''

|

||||

def __init__(self):

|

||||

pygame.sprite.Sprite.__init__(self)

|

||||

self.images = []

|

||||

img = pygame.image.load(os.path.join('images','hero.png')).convert()

|

||||

self.images.append(img)

|

||||

self.image = self.images[0]

|

||||

self.rect = self.image.get_rect()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

如果你的可操控角色拥有一个走路循环,在 `images` 文件夹中将对应图片保存为 `hero1.png` 到 `hero4.png` 的独立文件。

|

||||

|

||||

使用一个循环来告诉 Python 遍历每个文件。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

'''

|

||||

对象

|

||||

'''

|

||||

|

||||

class Player(pygame.sprite.Sprite):

|

||||

'''

|

||||

生成一个玩家

|

||||

'''

|

||||

def __init__(self):

|

||||

pygame.sprite.Sprite.__init__(self)

|

||||

self.images = []

|

||||

for i in range(1,5):

|

||||

img = pygame.image.load(os.path.join('images','hero' + str(i) + '.png')).convert()

|

||||

self.images.append(img)

|

||||

self.image = self.images[0]

|

||||

self.rect = self.image.get_rect()

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

### 将玩家带入游戏世界

|

||||

|

||||

现在一个 Player 类已经创建好了,你需要使用它在你的游戏世界中生成一个玩家妖精。如果你不调用 Player 类,那它永远不会起作用,(游戏世界中)也就不会有玩家。你可以通过立马运行你的游戏来验证一下。游戏会像上一篇文章末尾看到的那样运行,并得到明确的结果:一个空荡荡的游戏世界。

|

||||

|

||||

为了将一个玩家妖精带到你的游戏世界,你必须通过调用 Player 类来生成一个妖精,并将它加入到 Pygame 的妖精组中。在如下的代码示例中,前三行是已经存在的代码,你需要在其后添加代码:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

world = pygame.display.set_mode([worldx,worldy])

|

||||

backdrop = pygame.image.load(os.path.join('images','stage.png')).convert()

|

||||

backdropbox = screen.get_rect()

|

||||

|

||||

# 以下是新代码

|

||||

|

||||

player = Player() # 生成玩家

|

||||

player.rect.x = 0 # 移动 x 坐标

|

||||

player.rect.y = 0 # 移动 y 坐标

|

||||

player_list = pygame.sprite.Group()

|

||||

player_list.add(player)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

尝试启动你的游戏来看看发生了什么。高能预警:它不会像你预期的那样工作,当你启动你的项目,玩家妖精没有出现。事实上它生成了,只不过只出现了一毫秒。你要如何修复一个只出现了一毫秒的东西呢?你可能回想起上一篇文章中,你需要在主循环中添加一些东西。为了使玩家的存在时间超过一毫秒,你需要告诉 Python 在每次循环中都绘制一次。

|

||||

|

||||

将你的循环底部的语句更改如下:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

world.blit(backdrop, backdropbox)

|

||||

player_list.draw(screen) # 绘制玩家

|

||||

pygame.display.flip()

|

||||

clock.tick(fps)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

现在启动你的游戏,你的玩家出现了!

|

||||

|

||||

### 设置 alpha 通道

|

||||

|

||||

根据你如何创建你的玩家妖精,在它周围可能会有一个色块。你所看到的是 alpha 通道应该占据的空间。它本来是不可见的“颜色”,但 Python 现在还不知道要使它不可见。那么你所看到的,是围绕在妖精周围的边界区(或现代游戏术语中的“命中区”)内的空间。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

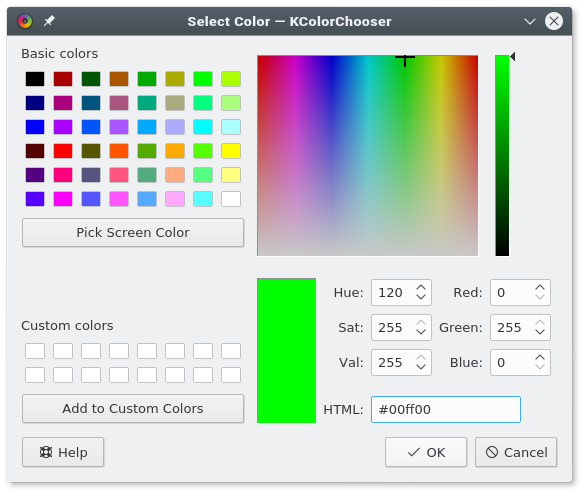

你可以通过设置一个 alpha 通道和 RGB 值来告诉 Python 使哪种颜色不可见。如果你不知道你使用 alpha 通道的图像的 RGB 值,你可以使用 Krita 或 Inkscape 打开它,并使用一种独特的颜色,比如 #00ff00(差不多是“绿屏绿”)来填充图像周围的空白区域。记下颜色对应的十六进制值(此处为 #00ff00,绿屏绿)并将其作为 alpha 通道用于你的 Python 脚本。

|

||||

|

||||

使用 alpha 通道需要在你的妖精生成相关代码中添加如下两行。类似第一行的代码已经存在于你的脚本中,你只需要添加另外两行:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

img = pygame.image.load(os.path.join('images','hero' + str(i) + '.png')).convert()

|

||||

img.convert_alpha() # 优化 alpha

|

||||

img.set_colorkey(ALPHA) # 设置 alpha

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

除非你告诉它,否则 Python 不知道将哪种颜色作为 alpha 通道。在你代码的设置相关区域,添加一些颜色定义。将如下的变量定义添加于你的设置相关区域的任意位置:

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

ALPHA = (0, 255, 0)

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

在以上示例代码中,**0,255,0** 被我们使用,它在 RGB 中所代表的值与 #00ff00 在十六进制中所代表的值相同。你可以通过一个优秀的图像应用程序,如 [GIMP][7]、Krita 或 Inkscape,来获取所有这些颜色值。或者,你可以使用一个优秀的系统级颜色选择器,如 [KColorChooser][8],来检测颜色。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

如果你的图像应用程序将你的妖精背景渲染成了其他的值,你可以按需调整 ``ALPHA`` 变量的值。不论你将 alpha 设为多少,最后它都将“不可见”。RGB 颜色值是非常严格的,因此如果你需要将 alpha 设为 000,但你又想将 000 用于你图像中的黑线,你只需要将图像中线的颜色设为 111。这样一来,(图像中的黑线)就足够接近黑色,但除了电脑以外没有人能看出区别。

|

||||

|

||||

运行你的游戏查看结果。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

在 [这个系列的第四篇文章][9] 中,我会向你们展示如何使你的妖精动起来。多么的激动人心啊!

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://opensource.com/article/17/12/game-python-add-a-player

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Seth Kenlon][a]

|

||||

选题:[lujun9972][b]

|

||||

译者:[cycoe](https://github.com/cycoe)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]: https://opensource.com/users/seth

|

||||

[b]: https://github.com/lujun9972

|

||||

[1]: https://opensource.com/article/17/10/python-101

|

||||

[2]: https://opensource.com/article/17/12/program-game-python-part-2-creating-game-world

|

||||

[3]: http://krita.org

|

||||

[4]: http://inkscape.org

|

||||

[5]: http://openclipart.org

|

||||

[6]: https://opengameart.org/

|

||||

[7]: http://gimp.org

|

||||

[8]: https://github.com/KDE/kcolorchooser

|

||||

[9]: https://opensource.com/article/17/12/program-game-python-part-4-moving-your-sprite

|

||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user