mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-03-27 02:30:10 +08:00

20141112-2 选题

This commit is contained in:

parent

c38e4f98c8

commit

17560fdd5d

@ -0,0 +1,154 @@

|

||||

How to Debug CPU Regressions Using Flame Graphs

|

||||

================================================================================

|

||||

How quickly can you debug a CPU performance regression? If your environment is complex and changing quickly, this becomes challenging with existing tools. If it takes a week to root cause a regression, the code may have changed multiple times, and now you have new regressions to debug.

|

||||

|

||||

Debugging CPU usage is easy in most cases, thanks to [CPU flame graphs][1]. To debug regressions, I would load before and after flame graphs in separate browser tabs, and then blink between them like searching for [Pluto][2]. It got the job done, but I wondered about a better way.

|

||||

|

||||

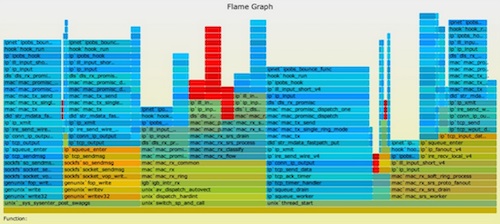

Introducing **red/blue differential flame graphs**:

|

||||

|

||||

<p><object data="http://www.brendangregg.com/blog/images/2014/zfs-flamegraph-diff.svg" type="image/svg+xml" width=720 height=296>

|

||||

<img src="http://www.brendangregg.com/blog/images/2014/zfs-flamegraph-diff.svg" width=720 />

|

||||

</object></p>

|

||||

|

||||

This is an interactive SVG (direct [link][3]). The color shows **red for growth**, and **blue for reductions**.

|

||||

|

||||

The size and shape of the flame graph is the same as a CPU flame graph for the second profile (y-axis is stack depth, x-axis is population, and the width of each frame is proportional to its presence in the profile; the top edge is what's actually running on CPU, and everything beneath it is ancestry.)

|

||||

|

||||

In this example, a workload saw a CPU increase after a system update. Here's the CPU flame graph ([SVG][4]):

|

||||

|

||||

<p><object data="http://www.brendangregg.com/blog/images/2014/zfs-flamegraph-after.svg" type="image/svg+xml" width=720 height=296>

|

||||

<img src="http://www.brendangregg.com/blog/images/2014/zfs-flamegraph-after.svg" width=720 />

|

||||

</object></p>

|

||||

|

||||

Normally, the colors are picked at random to differentiate frames and towers. Red/blue differential flame graphs use color to show the difference between two profiles.

|

||||

|

||||

The deflate_slow() code and children were running more in the second profile, highlighted earlier as red frames. The cause was that ZFS compression was enabled in the system update, which it wasn't previously.

|

||||

|

||||

While this makes for a clear example, I didn't really need a differential flame graph for this one. Imagine tracking down subtle regressions, of less than 5%, and where the code is also more complex.

|

||||

|

||||

### Red/Blue Differential Flame Graphs ###

|

||||

|

||||

I've had many discussions about this for years, and finally wrote an implementation that I hope makes sense. It works like this:

|

||||

|

||||

1. Take stack profile 1.

|

||||

1. Take stack profile 2.

|

||||

1. Generate a flame graph using 2. (This sets the width of all frames using profile 2.)

|

||||

1. Colorize the flame graph using the "2 - 1" delta. If a frame appeared more times in 2, it is red, less times, it is blue. The saturation is relative to the delta.

|

||||

|

||||

The intent is for use with before & after profiles, such as for **non-regression testing** or benchmarking code changes. The flame graph is drawn using the "after" profile (such that the frame widths show the current CPU consumption), and then colorized by the delta to show how we got there.

|

||||

|

||||

The colors show the difference that function directly contributed (eg, being on-CPU), not its children.

|

||||

|

||||

### Generation ###

|

||||

|

||||

I've pushed a simple implementation to github (see [FlameGraph][5]), which includes a new program, difffolded.pl. To show how it works, here are the steps using Linux [perf_events][6] (you can use other profilers).

|

||||

|

||||

#### Collect profile 1: ####

|

||||

|

||||

# perf record -F 99 -a -g -- sleep 30

|

||||

# perf script > out.stacks1

|

||||

|

||||

#### Some time later (or after a code change), collect profile 2: ####

|

||||

|

||||

# perf record -F 99 -a -g -- sleep 30

|

||||

# perf script > out.stacks2

|

||||

|

||||

#### Now fold these profile files, and generate a differential flame graph: ####

|

||||

|

||||

$ git clone --depth 1 http://github.com/brendangregg/FlameGraph

|

||||

$ cd FlameGraph

|

||||

$ ./stackcollapse-perf.pl ../out.stacks1 > out.folded1

|

||||

$ ./stackcollapse-perf.pl ../out.stacks2 > out.folded2

|

||||

$ ./difffolded.pl out.folded1 out.folded2 | ./flamegraph.pl > diff2.svg

|

||||

|

||||

difffolded.pl operates on the "folded" style of stack profiles, which are generated by the stackcollapse collection of tools (see the files in [FlameGraph][7]). It emits a three column output, with the folded stack trace and two value columns, one for each profile. Eg:

|

||||

|

||||

func_a;func_b;func_c 31 33

|

||||

[...]

|

||||

|

||||

This would mean the stack composed of "func_a()->func_b()->func_c()" was seen 31 times in profile 1, and in 33 times in profile 2. If flamegraph.pl is handed this three column input, it will automatically generate a red/blue differential flame graph.

|

||||

|

||||

### Options ###

|

||||

|

||||

Some options you'll want to know about:

|

||||

|

||||

**difffolded.pl -n**: This normalizes the first profile count to match the second. If you don't do this, and take profiles at different times of day, then all the stack counts will naturally differ due to varied load. Everything will look red if the load increased, or blue if load decreased. The -n option balances the first profile, so you get the full red/blue spectrum.

|

||||

|

||||

**difffolded.pl -x**: This strips hex addresses. Sometimes profilers can't translate addresses into symbols, and include raw hex addresses. If these addresses differ between profiles, then they'll be shown as differences, when in fact the executed function was the same. Fix with -x.

|

||||

|

||||

**flamegraph.pl --negate**: Inverts the red/blue scale. See the next section.

|

||||

|

||||

### Negation ###

|

||||

|

||||

While my red/blue differential flame graphs are useful, there is a problem: if code paths vanish completely in the second profile, then there's nothing to color blue. You'll be looking at the current CPU usage, but missing information on how we got there.

|

||||

|

||||

One solution is to reverse the order of the profiles and draw a negated flame graph differential. Eg:

|

||||

|

||||

<p><object data="http://www.brendangregg.com/blog/images/2014/zfs-flamegraph-negated.svg" type="image/svg+xml" width=720 height=296>

|

||||

<img src="http://www.brendangregg.com/blog/images/2014/zfs-flamegraph-negated.svg" width=720 />

|

||||

</object></p>

|

||||

|

||||

Now the widths show the first profile, and the colors show what will happen. The blue highlighting on the right shows we're about to spend a lot less time in the CPU idle path. (Note that I usually filter out cpu_idle from the folded files, by including a grep -v cpu_idle.)

|

||||

|

||||

This also highlights the vanishing code problem (or rather, doesn't highlight), as since compression wasn't enabled in the "before" profile, there is nothing to color red.

|

||||

|

||||

This was generated using:

|

||||

|

||||

$ ./difffolded.pl out.folded2 out.folded1 | ./flamegraph.pl --negate > diff1.svg

|

||||

|

||||

Which, along with the earlier diff2.svg, gives us:

|

||||

|

||||

- **diff1.svg**: widths show the before profile, colored by what WILL happen

|

||||

- **diff2.svg**: widths show the after profile, colored by what DID happen

|

||||

|

||||

If I were to automate this for non-regression testing, I'd generate and show both side by side.

|

||||

|

||||

### CPI Flame Graphs ###

|

||||

|

||||

I first used this code for my [CPI flame graphs][8], where instead of doing a difference between two profiles, I showed the difference between CPU cycles and stall cycles, which highlights what the CPUs were doing.

|

||||

|

||||

### Other Differential Flame Graphs ###

|

||||

|

||||

[][9]

|

||||

|

||||

There's other ways flame graph differentials can be done. [Robert Mustacchi][10] experimented with [differentials][11] a while ago, and used an approach similar to a colored code review: only the difference is shown, colored red for added (increased) code paths, and blue for removed (decreased) code paths. The key difference is that the frame widths are now relative to the size of the difference only. An example is on the right. It's a good idea, but in practice I found it a bit weird, and hard to follow without the bigger picture context: a standard flame graph showing the full profile.

|

||||

|

||||

[][12]

|

||||

|

||||

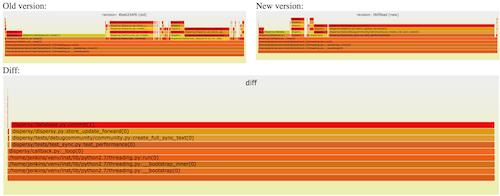

Cor-Paul Bezemer has created [flamegraphdiff][13], which shows the profile difference using three flame graphs at the same time: the standard before and after flame graphs, and then a differential flame graph where the widths show the difference. See the [example][14]. You can mouse-over frames in the differential, which highlights frames in all profiles. This solves the context problem, since you can see the standard flame graph profiles.

|

||||

|

||||

My red/blue flame graphs, Robert's hue differential, and Cor-Paul's triple-view, all have their strengths. These could be combined: the top two flame graphs in Cor-Paul's view could be my diff1.svg and diff2.svg. Then the bottom flame graph colored using Robert's approach. For consistency, the bottom flame graph could use the same palette range as mine: blue->white->red.

|

||||

|

||||

Flame graphs are spreading, and are now used by many companies. I wouldn't be surprised if there were already other implementations of flame graph differentials I didn't know about. (Leave a comment!)

|

||||

|

||||

### Conclusion ###

|

||||

|

||||

If you have problems with performance regressions, red/blue differential flame graphs may be the quickest way to find the root cause. These take a normal flame graph and then use colors to show the difference between two profiles: red for greater samples, and blue for fewer. The size and shape of the flame graph shows the current ("after") profile, so that you can easily see where the samples are based on the widths, and then the colors show how we got there: the profile difference.

|

||||

|

||||

These differential flame graphs could also be generated by a nightly non-regression test suite, so that performance regressions can be quickly debugged after the fact.

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: http://www.brendangregg.com/blog/2014-11-09/differential-flame-graphs.html

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Brendan Gregg][a]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创翻译,[Linux中国](http://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:http://www.linux.com/community/forums/person/60160

|

||||

[1]:http://www.brendangregg.com/FlameGraphs/cpuflamegraphs.html

|

||||

[2]:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planets_beyond_Neptune#Discovery_of_Pluto

|

||||

[3]:http://www.brendangregg.com/blog/images/2014/zfs-flamegraph-diff.svg

|

||||

[4]:http://www.brendangregg.com/blog/images/2014/zfs-flamegraph-after.svg

|

||||

[5]:https://github.com/brendangregg/FlameGraph

|

||||

[6]:http://www.brendangregg.com/perf.html

|

||||

[7]:https://github.com/brendangregg/FlameGraph

|

||||

[8]:http://www.brendangregg.com/blog/2014-10-31/cpi-flame-graphs.html

|

||||

[9]:http://www.slideshare.net/brendangregg/blazing-performance-with-flame-graphs/167

|

||||

[10]:http://dtrace.org/blogs/rm

|

||||

[11]:http://www.slideshare.net/brendangregg/blazing-performance-with-flame-graphs/167

|

||||

[12]:https://github.com/corpaul/flamegraphdiff

|

||||

[13]:http://corpaul.github.io/flamegraphdiff/

|

||||

[14]:http://corpaul.github.io/flamegraphdiff/demos/dispersy/dispersy_diff.html

|

||||

@ -0,0 +1,127 @@

|

||||

Intro to Systemd Runlevels and Service Management Commands

|

||||

================================================================================

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

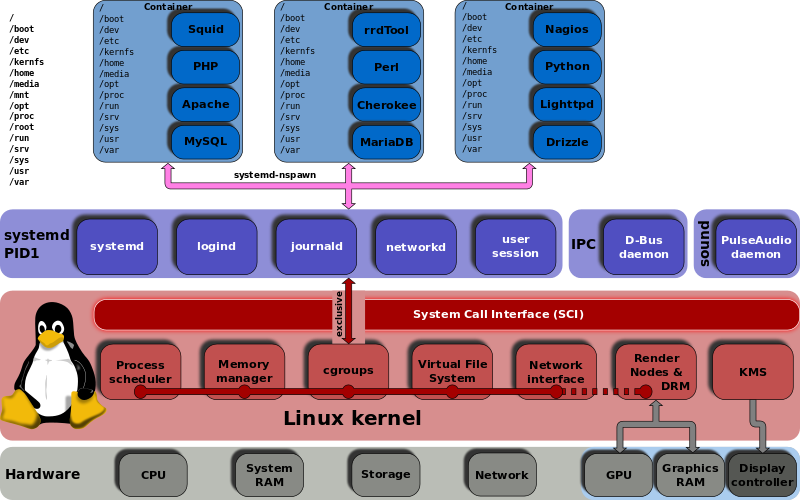

In olden times we had static runlevels. systemd has mechanisms for more flexible and dynamic control of your system.

|

||||

|

||||

Before we get into learning more useful systemd commands, let's take a little trip down memory lane. There is this weird dichotomy in Linux-land, where Linux and FOSS are always pushing ahead and progressing, and people are always complaining about it. Which is why I am taking all of this anti-systemd uproar with a grain of salt, because I remember when:

|

||||

|

||||

- Packages were evil, because real Linux users built everything from source code and kept strict control of what went on their systems.

|

||||

- Dependency-resolving package managers were evil, because real Linux users resolved dependency hells manually.

|

||||

- Except for apt-get, which was always good, so only Yum was evil.

|

||||

- Because Red Hat was the Microsoft of Linux.

|

||||

- Yay Ubuntu!

|

||||

- Boo hiss Ubuntu!

|

||||

|

||||

And on and on...as I have said lo so many times before, changes are upsetting. They mess with our workflow, which is no small thing because any disruption has a real productivity cost. But we are still in the infant stage of computing, so it's going to keep changing and advancing rapidly for a long time. I'm sure you know people who are stuck in the mindset that once you buy something, like a wrench or a piece of furniture or a pink flamingo lawn ornament, it is forever. These are the people who are still running Windows Vista, or deity help us Windows 95 on some ancient, feeble PC with a CRT monitor, and who don't understand why you keep bugging them to replace it. It still works, right?

|

||||

|

||||

Which reminds me of my greatest triumph in keeping an old computer running long after it should have been retired. Once upon a time a friend had this little old 286 running some ancient version of MS-DOS. She used it for a few basic tasks like appointments, diary, and a little old accounting program that I wrote in BASIC for her check register. Who cares about security updates, right? It's not connected to any network. So from time to time I replaced the occasional failed resistor or capacitor, power supply, and CMOS battery. It just kept going. Her tiny old amber CRT monitor grew dimmer and dimmer, and finally it died after 20+ years of service. Now she is using an old Thinkpad running Linux for the same tasks.

|

||||

|

||||

If there is a moral to this tangent it escapes me, so let's get busy with systemd.

|

||||

|

||||

### Runlevels vs. States ###

|

||||

|

||||

SysVInit uses static runlevels to create different states to boot into, and most distros use five:

|

||||

|

||||

- Single-user mode

|

||||

- Multi-user mode without network services started

|

||||

- Multi-user mode with network services started

|

||||

- System shutdown

|

||||

- System reboot.

|

||||

|

||||

Me, I don't see a lot of practical value in having multiple runlevels, but there they are. Instead of runlevels, systemd allows you to create different states, which gives you a flexible mechanism for creating different configurations to boot into. These states are composed of multiple unit files bundled into targets. Targets have nice descriptive names instead of numbers. Unit files control services, devices, sockets, and mounts. You can see what these look like by examining the prefab targets that come with systemd, for example /usr/lib/systemd/system/graphical.target, which is the default on CentOS 7:

|

||||

|

||||

[Unit]

|

||||

Description=Graphical Interface

|

||||

Documentation=man:systemd.special(7)

|

||||

Requires=multi-user.target

|

||||

After=multi-user.target

|

||||

Conflicts=rescue.target

|

||||

Wants=display-manager.service

|

||||

AllowIsolate=yes

|

||||

[Install]

|

||||

Alias=default.target

|

||||

|

||||

So what do unit files look like? Let us peer into one. Unit files are in two directories:

|

||||

|

||||

- /etc/systemd/system/

|

||||

- /usr/lib/systemd/system/

|

||||

|

||||

The first one is for us to play with, and the second one is where packages install unit files. **/etc/systemd/system/** takes precedence over **/usr/lib/systemd/system/**. Hurrah, human over machine. This is the unit file for the Apache Web server:

|

||||

|

||||

[Unit]

|

||||

Description=The Apache HTTP Server

|

||||

After=network.target remote-fs.target nss-lookup.target

|

||||

[Service]

|

||||

Type=notify

|

||||

EnvironmentFile=/etc/sysconfig/httpd

|

||||

ExecStart=/usr/sbin/httpd/ $OPTIONS -DFOREGROUND

|

||||

ExecReload=/usr/sbin/httpd $OPTIONS -k graceful

|

||||

ExecStop=/bin/kill -WINCH ${MAINPID}

|

||||

KillSignal=SIGCONT

|

||||

PrivateTmp=true

|

||||

[Install]

|

||||

WantedBy=multi.user.target

|

||||

|

||||

These files are fairly understandable even for systemd newcomers, and unit files are quite a bit simpler than a SysVInit init file, as this snippet from /etc/init.d/apache2 shows:

|

||||

|

||||

SCRIPTNAME="${0##*/}"

|

||||

SCRIPTNAME="${SCRIPTNAME##[KS][0-9][0-9]}"

|

||||

if [ -n "$APACHE_CONFDIR" ] ; then

|

||||

if [ "${APACHE_CONFDIR##/etc/apache2-}" != "${APACHE_CONFDIR}" ] ; then

|

||||

DIR_SUFFIX="${APACHE_CONFDIR##/etc/apache2-}"

|

||||

else

|

||||

DIR_SUFFIX=

|

||||

|

||||

The whole file is 410 lines.

|

||||

|

||||

You can view unit dependencies, and it's always surprising to me how complex they are:

|

||||

|

||||

$ systemctl list-dependencies httpd.service

|

||||

|

||||

### cgroups ###

|

||||

|

||||

cgroups, or control groups, have been present in the Linux kernel for some years, but have not been used very much until systemd. [The kernel documentation][1] says: "Control Groups provide a mechanism for aggregating/partitioning sets of tasks, and all their future children, into hierarchical groups with specialized behaviour." In other words, it has the potential to control, limit, and allocate resources in multiple useful ways. systemd uses cgroups, and you can see them. This displays your entire cgroup tree:

|

||||

|

||||

$ systemd-cgls

|

||||

|

||||

You can generate a different view with the good old ps command:

|

||||

|

||||

$ ps xawf -eo pid,user,cgroup,args

|

||||

|

||||

### Useful Commands ###

|

||||

|

||||

This command reloads the configuration file of a daemon, and not its systemd service file. Use this when you make a configuration change and want to activate it with least disruption, like this example for Apache:

|

||||

|

||||

# systemctl reload httpd.service

|

||||

|

||||

Reloading a service file completely stops and then restarts a service. If it is not running this starts it:

|

||||

|

||||

# systemctl restart httpd.service

|

||||

|

||||

You can restart all daemons with one command. This reloads all unit files, and re-creates the whole systemd dependency tree:

|

||||

|

||||

# systemctl daemon-reload

|

||||

|

||||

You can reboot, suspend, and poweroff as an ordinary unprivileged user:

|

||||

|

||||

$ systemctl reboot

|

||||

$ systemctl suspend

|

||||

$ systemctl poweroff

|

||||

|

||||

As always, there is much, much more to learn about systemd. [Here We Go Again, Another Linux Init: Intro to systemd][2] and [Understanding and Using Systemd][3] are good introductions to systemd, with links to more detailed resources.

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: http://www.linux.com/learn/tutorials/794615-systemd-runlevels-and-service-management

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[Carla Schroder][a]

|

||||

译者:[译者ID](https://github.com/译者ID)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创翻译,[Linux中国](http://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:http://www.linux.com/community/forums/person/3734

|

||||

[1]:https://www.kernel.org/doc/Documentation/cgroups/cgroups.txt

|

||||

[2]:http://www.linux.com/learn/tutorials/524577-here-we-go-again-another-linux-init-intro-to-systemd

|

||||

[3]:http://www.linux.com/learn/tutorials/788613-understanding-and-using-systemd

|

||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user