mirror of

https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject.git

synced 2025-02-06 23:50:16 +08:00

Merge pull request #6425 from yongshouzhang/master

翻译 A user's guide to links in the Linux filesystem

This commit is contained in:

commit

16d2157301

@ -1,314 +0,0 @@

|

||||

Translating by yongshouzhang

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

A user's guide to links in the Linux filesystem

|

||||

============================================================

|

||||

|

||||

### Learn how to use links, which make tasks easier by providing access to files from multiple locations in the Linux filesystem directory tree.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Image by : [Paul Lewin][8]. Modified by Opensource.com. [CC BY-SA 2.0][9]

|

||||

|

||||

In articles I have written about various aspects of Linux filesystems for Opensource.com, including [An introduction to Linux's EXT4 filesystem][10]; [Managing devices in Linux][11]; [An introduction to Linux filesystems][12]; and [A Linux user's guide to Logical Volume Management][13], I have briefly mentioned an interesting feature of Linux filesystems that can make some tasks easier by providing access to files from multiple locations in the filesystem directory tree.

|

||||

|

||||

There are two types of Linux filesystem links: hard and soft. The difference between the two types of links is significant, but both types are used to solve similar problems. They both provide multiple directory entries (or references) to a single file, but they do it quite differently. Links are powerful and add flexibility to Linux filesystems because [everything is a file][14].

|

||||

|

||||

More Linux resources

|

||||

|

||||

* [What is Linux?][1]

|

||||

|

||||

* [What are Linux containers?][2]

|

||||

|

||||

* [Download Now: Linux commands cheat sheet][3]

|

||||

|

||||

* [Advanced Linux commands cheat sheet][4]

|

||||

|

||||

* [Our latest Linux articles][5]

|

||||

|

||||

I have found, for instance, that some programs required a particular version of a library. When a library upgrade replaced the old version, the program would crash with an error specifying the name of the old, now-missing library. Usually, the only change in the library name was the version number. Acting on a hunch, I simply added a link to the new library but named the link after the old library name. I tried the program again and it worked perfectly. And, okay, the program was a game, and everyone knows the lengths that gamers will go to in order to keep their games running.

|

||||

|

||||

In fact, almost all applications are linked to libraries using a generic name with only a major version number in the link name, while the link points to the actual library file that also has a minor version number. In other instances, required files have been moved from one directory to another to comply with the Linux file specification, and there are links in the old directories for backwards compatibility with those programs that have not yet caught up with the new locations. If you do a long listing of the **/lib64** directory, you can find many examples of both.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

lrwxrwxrwx. 1 root root 36 Dec 8 2016 cracklib_dict.hwm -> ../../usr/share/cracklib/pw_dict.hwm

|

||||

lrwxrwxrwx. 1 root root 36 Dec 8 2016 cracklib_dict.pwd -> ../../usr/share/cracklib/pw_dict.pwd

|

||||

lrwxrwxrwx. 1 root root 36 Dec 8 2016 cracklib_dict.pwi -> ../../usr/share/cracklib/pw_dict.pwi

|

||||

lrwxrwxrwx. 1 root root 27 Jun 9 2016 libaccountsservice.so.0 -> libaccountsservice.so.0.0.0

|

||||

-rwxr-xr-x. 1 root root 288456 Jun 9 2016 libaccountsservice.so.0.0.0

|

||||

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 15 May 17 11:47 libacl.so.1 -> libacl.so.1.1.0

|

||||

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 36472 May 17 11:47 libacl.so.1.1.0

|

||||

lrwxrwxrwx. 1 root root 15 Feb 4 2016 libaio.so.1 -> libaio.so.1.0.1

|

||||

-rwxr-xr-x. 1 root root 6224 Feb 4 2016 libaio.so.1.0.0

|

||||

-rwxr-xr-x. 1 root root 6224 Feb 4 2016 libaio.so.1.0.1

|

||||

lrwxrwxrwx. 1 root root 30 Jan 16 16:39 libakonadi-calendar.so.4 -> libakonadi-calendar.so.4.14.26

|

||||

-rwxr-xr-x. 1 root root 816160 Jan 16 16:39 libakonadi-calendar.so.4.14.26

|

||||

lrwxrwxrwx. 1 root root 29 Jan 16 16:39 libakonadi-contact.so.4 -> libakonadi-contact.so.4.14.26

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

A few of the links in the **/lib64** directory

|

||||

|

||||

The long listing of the **/lib64** directory above shows that the first character in the filemode is the letter "l," which means that each is a soft or symbolic link.

|

||||

|

||||

### Hard links

|

||||

|

||||

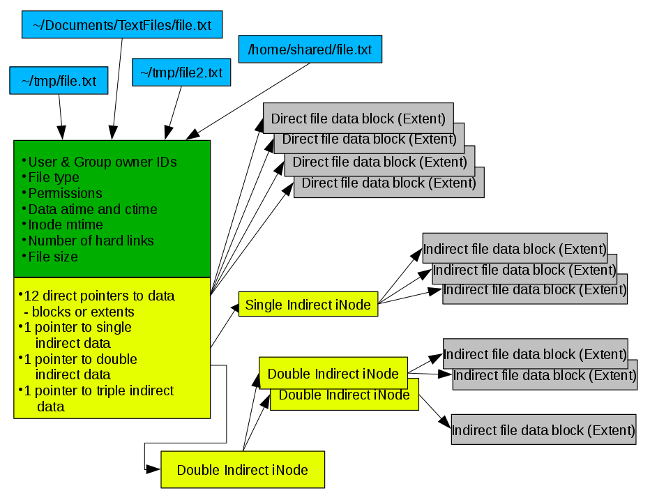

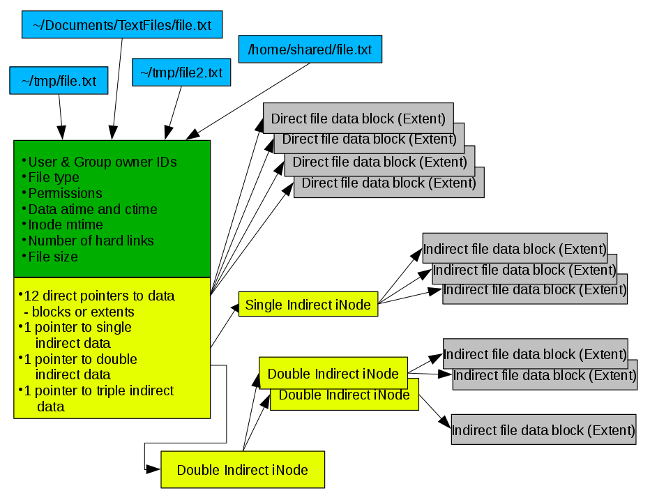

In [An introduction to Linux's EXT4 filesystem][15], I discussed the fact that each file has one inode that contains information about that file, including the location of the data belonging to that file. [Figure 2][16] in that article shows a single directory entry that points to the inode. Every file must have at least one directory entry that points to the inode that describes the file. The directory entry is a hard link, thus every file has at least one hard link.

|

||||

|

||||

In Figure 1 below, multiple directory entries point to a single inode. These are all hard links. I have abbreviated the locations of three of the directory entries using the tilde (**~**) convention for the home directory, so that **~** is equivalent to **/home/user** in this example. Note that the fourth directory entry is in a completely different directory, **/home/shared**, which might be a location for sharing files between users of the computer.

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Figure 1

|

||||

|

||||

Hard links are limited to files contained within a single filesystem. "Filesystem" is used here in the sense of a partition or logical volume (LV) that is mounted on a specified mount point, in this case **/home**. This is because inode numbers are unique only within each filesystem, and a different filesystem, for example, **/var**or **/opt**, will have inodes with the same number as the inode for our file.

|

||||

|

||||

Because all the hard links point to the single inode that contains the metadata about the file, all of these attributes are part of the file, such as ownerships, permissions, and the total number of hard links to the inode, and cannot be different for each hard link. It is one file with one set of attributes. The only attribute that can be different is the file name, which is not contained in the inode. Hard links to a single **file/inode** located in the same directory must have different names, due to the fact that there can be no duplicate file names within a single directory.

|

||||

|

||||

The number of hard links for a file is displayed with the **ls -l** command. If you want to display the actual inode numbers, the command **ls -li** does that.

|

||||

|

||||

### Symbolic (soft) links

|

||||

|

||||

The difference between a hard link and a soft link, also known as a symbolic link (or symlink), is that, while hard links point directly to the inode belonging to the file, soft links point to a directory entry, i.e., one of the hard links. Because soft links point to a hard link for the file and not the inode, they are not dependent upon the inode number and can work across filesystems, spanning partitions and LVs.

|

||||

|

||||

The downside to this is: If the hard link to which the symlink points is deleted or renamed, the symlink is broken. The symlink is still there, but it points to a hard link that no longer exists. Fortunately, the **ls** command highlights broken links with flashing white text on a red background in a long listing.

|

||||

|

||||

### Lab project: experimenting with links

|

||||

|

||||

I think the easiest way to understand the use of and differences between hard and soft links is with a lab project that you can do. This project should be done in an empty directory as a _non-root user_ . I created the **~/temp** directory for this project, and you should, too. It creates a safe place to do the project and provides a new, empty directory to work in so that only files associated with this project will be located there.

|

||||

|

||||

### **Initial setup**

|

||||

|

||||

First, create the temporary directory in which you will perform the tasks needed for this project. Ensure that the present working directory (PWD) is your home directory, then enter the following command.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

mkdir temp

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Change into **~/temp** to make it the PWD with this command.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

cd temp

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

To get started, we need to create a file we can link to. The following command does that and provides some content as well.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

du -h > main.file.txt

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Use the **ls -l** long list to verify that the file was created correctly. It should look similar to my results. Note that the file size is only 7 bytes, but yours may vary by a byte or two.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ls -l

|

||||

total 4

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 1 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 main.file.txt

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Notice the number "1" following the file mode in the listing. That number represents the number of hard links that exist for the file. For now, it should be 1 because we have not created any additional links to our test file.

|

||||

|

||||

### **Experimenting with hard links**

|

||||

|

||||

Hard links create a new directory entry pointing to the same inode, so when hard links are added to a file, you will see the number of links increase. Ensure that the PWD is still **~/temp**. Create a hard link to the file **main.file.txt**, then do another long list of the directory.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ln main.file.txt link1.file.txt

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ls -l

|

||||

total 8

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 2 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 link1.file.txt

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 2 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 main.file.txt

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Notice that both files have two links and are exactly the same size. The date stamp is also the same. This is really one file with one inode and two links, i.e., directory entries to it. Create a second hard link to this file and list the directory contents. You can create the link to either of the existing ones: **link1.file.txt** or **main.file.txt**.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ln link1.file.txt link2.file.txt ; ls -l

|

||||

total 16

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 3 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 link1.file.txt

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 3 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 link2.file.txt

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 3 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 main.file.txt

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Notice that each new hard link in this directory must have a different name because two files—really directory entries—cannot have the same name within the same directory. Try to create another link with a target name the same as one of the existing ones.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ln main.file.txt link2.file.txt

|

||||

ln: failed to create hard link 'link2.file.txt': File exists

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Clearly that does not work, because **link2.file.txt** already exists. So far, we have created only hard links in the same directory. So, create a link in your home directory, the parent of the temp directory in which we have been working so far.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ln main.file.txt ../main.file.txt ; ls -l ../main*

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 main.file.txt

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The **ls** command in the above listing shows that the **main.file.txt** file does exist in the home directory with the same name as the file in the temp directory. Of course, these are not different files; they are the same file with multiple links—directory entries—to the same inode. To help illustrate the next point, add a file that is not a link.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ touch unlinked.file ; ls -l

|

||||

total 12

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 link1.file.txt

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 link2.file.txt

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 main.file.txt

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 1 dboth dboth 0 Jun 14 08:18 unlinked.file

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Look at the inode number of the hard links and that of the new file using the **-i**option to the **ls** command.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ls -li

|

||||

total 12

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 link1.file.txt

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 link2.file.txt

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 main.file.txt

|

||||

657863 -rw-rw-r-- 1 dboth dboth 0 Jun 14 08:18 unlinked.file

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Notice the number **657024** to the left of the file mode in the example above. That is the inode number, and all three file links point to the same inode. You can use the **-i** option to view the inode number for the link we created in the home directory as well, and that will also show the same value. The inode number of the file that has only one link is different from the others. Note that the inode numbers will be different on your system.

|

||||

|

||||

Let's change the size of one of the hard-linked files.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ df -h > link2.file.txt ; ls -li

|

||||

total 12

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 link1.file.txt

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 link2.file.txt

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 main.file.txt

|

||||

657863 -rw-rw-r-- 1 dboth dboth 0 Jun 14 08:18 unlinked.file

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The file size of all the hard-linked files is now larger than before. That is because there is really only one file that is linked to by multiple directory entries.

|

||||

|

||||

I know this next experiment will work on my computer because my **/tmp**directory is on a separate LV. If you have a separate LV or a filesystem on a different partition (if you're not using LVs), determine whether or not you have access to that LV or partition. If you don't, you can try to insert a USB memory stick and mount it. If one of those options works for you, you can do this experiment.

|

||||

|

||||

Try to create a link to one of the files in your **~/temp** directory in **/tmp** (or wherever your different filesystem directory is located).

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ln link2.file.txt /tmp/link3.file.txt

|

||||

ln: failed to create hard link '/tmp/link3.file.txt' => 'link2.file.txt':

|

||||

Invalid cross-device link

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Why does this error occur? The reason is each separate mountable filesystem has its own set of inode numbers. Simply referring to a file by an inode number across the entire Linux directory structure can result in confusion because the same inode number can exist in each mounted filesystem.

|

||||

|

||||

There may be a time when you will want to locate all the hard links that belong to a single inode. You can find the inode number using the **ls -li** command. Then you can use the **find** command to locate all links with that inode number.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ find . -inum 657024

|

||||

./main.file.txt

|

||||

./link1.file.txt

|

||||

./link2.file.txt

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Note that the **find** command did not find all four of the hard links to this inode because we started at the current directory of **~/temp**. The **find** command only finds files in the PWD and its subdirectories. To find all the links, we can use the following command, which specifies your home directory as the starting place for the search.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ find ~ -samefile main.file.txt

|

||||

/home/dboth/temp/main.file.txt

|

||||

/home/dboth/temp/link1.file.txt

|

||||

/home/dboth/temp/link2.file.txt

|

||||

/home/dboth/main.file.txt

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

You may see error messages if you do not have permissions as a non-root user. This command also uses the **-samefile** option instead of specifying the inode number. This works the same as using the inode number and can be easier if you know the name of one of the hard links.

|

||||

|

||||

### **Experimenting with soft links**

|

||||

|

||||

As you have just seen, creating hard links is not possible across filesystem boundaries; that is, from a filesystem on one LV or partition to a filesystem on another. Soft links are a means to answer that problem with hard links. Although they can accomplish the same end, they are very different, and knowing these differences is important.

|

||||

|

||||

Let's start by creating a symlink in our **~/temp** directory to start our exploration.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ln -s link2.file.txt link3.file.txt ; ls -li

|

||||

total 12

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 link1.file.txt

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 link2.file.txt

|

||||

658270 lrwxrwxrwx 1 dboth dboth 14 Jun 14 15:21 link3.file.txt ->

|

||||

link2.file.txt

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 main.file.txt

|

||||

657863 -rw-rw-r-- 1 dboth dboth 0 Jun 14 08:18 unlinked.file

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The hard links, those that have the inode number **657024**, are unchanged, and the number of hard links shown for each has not changed. The newly created symlink has a different inode, number **658270**. The soft link named **link3.file.txt**points to **link2.file.txt**. Use the **cat** command to display the contents of **link3.file.txt**. The file mode information for the symlink starts with the letter "**l**" which indicates that this file is actually a symbolic link.

|

||||

|

||||

The size of the symlink **link3.file.txt** is only 14 bytes in the example above. That is the size of the text **link3.file.txt -> link2.file.txt**, which is the actual content of the directory entry. The directory entry **link3.file.txt** does not point to an inode; it points to another directory entry, which makes it useful for creating links that span file system boundaries. So, let's create that link we tried before from the **/tmp** directory.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ln -s /home/dboth/temp/link2.file.txt

|

||||

/tmp/link3.file.txt ; ls -l /tmp/link*

|

||||

lrwxrwxrwx 1 dboth dboth 31 Jun 14 21:53 /tmp/link3.file.txt ->

|

||||

/home/dboth/temp/link2.file.txt

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

### **Deleting links**

|

||||

|

||||

There are some other things that you should consider when you need to delete links or the files to which they point.

|

||||

|

||||

First, let's delete the link **main.file.txt**. Remember that every directory entry that points to an inode is simply a hard link.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ rm main.file.txt ; ls -li

|

||||

total 8

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 3 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 link1.file.txt

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 3 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 link2.file.txt

|

||||

658270 lrwxrwxrwx 1 dboth dboth 14 Jun 14 15:21 link3.file.txt ->

|

||||

link2.file.txt

|

||||

657863 -rw-rw-r-- 1 dboth dboth 0 Jun 14 08:18 unlinked.file

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

The link **main.file.txt** was the first link created when the file was created. Deleting it now still leaves the original file and its data on the hard drive along with all the remaining hard links. To delete the file and its data, you would have to delete all the remaining hard links.

|

||||

|

||||

Now delete the **link2.file.txt** hard link.

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ rm link2.file.txt ; ls -li

|

||||

total 8

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 3 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 link1.file.txt

|

||||

658270 lrwxrwxrwx 1 dboth dboth 14 Jun 14 15:21 link3.file.txt ->

|

||||

link2.file.txt

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 3 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 main.file.txt

|

||||

657863 -rw-rw-r-- 1 dboth dboth 0 Jun 14 08:18 unlinked.file

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

Notice what happens to the soft link. Deleting the hard link to which the soft link points leaves a broken link. On my system, the broken link is highlighted in colors and the target hard link is flashing. If the broken link needs to be fixed, you can create another hard link in the same directory with the same name as the old one, so long as not all the hard links have been deleted. You could also recreate the link itself, with the link maintaining the same name but pointing to one of the remaining hard links. Of course, if the soft link is no longer needed, it can be deleted with the **rm** command.

|

||||

|

||||

The **unlink** command can also be used to delete files and links. It is very simple and has no options, as the **rm** command does. It does, however, more accurately reflect the underlying process of deletion, in that it removes the link—the directory entry—to the file being deleted.

|

||||

|

||||

### Final thoughts

|

||||

|

||||

I worked with both types of links for a long time before I began to understand their capabilities and idiosyncrasies. It took writing a lab project for a Linux class I taught to fully appreciate how links work. This article is a simplification of what I taught in that class, and I hope it speeds your learning curve.

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

作者简介:

|

||||

|

||||

David Both - David Both is a Linux and Open Source advocate who resides in Raleigh, North Carolina. He has been in the IT industry for over forty years and taught OS/2 for IBM where he worked for over 20 years. While at IBM, he wrote the first training course for the original IBM PC in 1981. He has taught RHCE classes for Red Hat and has worked at MCI Worldcom, Cisco, and the State of North Carolina. He has been working with Linux and Open Source Software for almost 20 years.

|

||||

|

||||

---------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://opensource.com/article/17/6/linking-linux-filesystem

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[David Both ][a]

|

||||

译者:[runningwater](https://github.com/runningwater)

|

||||

校对:[校对者ID](https://github.com/校对者ID)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:https://opensource.com/users/dboth

|

||||

[1]:https://opensource.com/resources/what-is-linux?src=linux_resource_menu

|

||||

[2]:https://opensource.com/resources/what-are-linux-containers?src=linux_resource_menu

|

||||

[3]:https://developers.redhat.com/promotions/linux-cheatsheet/?intcmp=7016000000127cYAAQ

|

||||

[4]:https://developers.redhat.com/cheat-sheet/advanced-linux-commands-cheatsheet?src=linux_resource_menu&intcmp=7016000000127cYAAQ

|

||||

[5]:https://opensource.com/tags/linux?src=linux_resource_menu

|

||||

[6]:https://opensource.com/article/17/6/linking-linux-filesystem?rate=YebHxA-zgNopDQKKOyX3_r25hGvnZms_33sYBUq-SMM

|

||||

[7]:https://opensource.com/user/14106/feed

|

||||

[8]:https://www.flickr.com/photos/digypho/7905320090

|

||||

[9]:https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

|

||||

[10]:https://opensource.com/article/17/5/introduction-ext4-filesystem

|

||||

[11]:https://opensource.com/article/16/11/managing-devices-linux

|

||||

[12]:https://opensource.com/life/16/10/introduction-linux-filesystems

|

||||

[13]:https://opensource.com/business/16/9/linux-users-guide-lvm

|

||||

[14]:https://opensource.com/life/15/9/everything-is-a-file

|

||||

[15]:https://opensource.com/article/17/5/introduction-ext4-filesystem

|

||||

[16]:https://opensource.com/article/17/5/introduction-ext4-filesystem#fig2

|

||||

[17]:https://opensource.com/users/dboth

|

||||

[18]:https://opensource.com/article/17/6/linking-linux-filesystem#comments

|

||||

311

translated/tech/linux 文件链接用户指南.md

Normal file

311

translated/tech/linux 文件链接用户指南.md

Normal file

@ -0,0 +1,311 @@

|

||||

|

||||

linux 文件链接用户指南

|

||||

============================================================

|

||||

|

||||

### 学习如何使用链接,通过提供对 linux 文件系统多个位置的文件访问,来让日常工作变得轻松

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Image by : [Paul Lewin][8]. Modified by Opensource.com. [CC BY-SA 2.0][9]

|

||||

|

||||

在我为 opensource.com 写过的关于linux文件系统方方面面的文章中,包括 [An introduction to Linux's EXT4 filesystem][10]; [Managing devices in Linux][11]; [An introduction to Linux filesystems][12]; and [A Linux user's guide to Logical Volume Management][13],我曾简要的提到过linux文件系统一个有趣的特性,它允许用户访问linux文件目录树中多个位置的文件来简化一些任务

|

||||

|

||||

linux 文件系统中有两种链接:硬链接和软链接。虽然二者差别显著,但都用来解决相似的问题。它们都提供了对单个文件进行多个目录项的访问(引用),但实现却大为不同。链接的强大功能赋予了 linux 文件系统灵活性,因为[一切即文件][14]。

|

||||

|

||||

更多 linux 资源

|

||||

|

||||

* [什么是 linux ?][1]

|

||||

|

||||

* [什么是 linux 容器?][2]

|

||||

|

||||

* [现在下载: linux 命令速查表][3]

|

||||

|

||||

* [linux 高级命令速查表][4]

|

||||

|

||||

* [我们最新的 linux 文章][5]

|

||||

|

||||

举个例子,我曾发现一些程序要求特定的版本库方可运行。 当用升级后的库替代旧库后,程序会崩溃,提示就版本库缺失。 同城库中唯一变化是版本号。出于该直觉,我仅仅给程序添加了一个新的库链接,并以旧库名称命名。我试着再次启动程序,运行良好。 程序就是一个游戏,人人都明白,每个玩家都会尽力使游戏进行下去。

|

||||

|

||||

事实上,几乎所有的应用程序链接库都使用通用的命名规则,链接名称中包含了住版本号,链接所指文件的文件名中同样包含了最小版本号。再比如,程序的一些必需文件为了迎合 linux 文件系统的规范从一个目录移动到另一个目录中,系统为了向后兼容那些不能获取这些文件新位置的程序在旧的目录中存放了这些文件的链接。如果你对 /lib64 目录做一个长清单列表,你会发现很多这样的例子。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

lrwxrwxrwx. 1 root root 36 Dec 8 2016 cracklib_dict.hwm -> ../../usr/share/cracklib/pw_dict.hwm

|

||||

lrwxrwxrwx. 1 root root 36 Dec 8 2016 cracklib_dict.pwd -> ../../usr/share/cracklib/pw_dict.pwd

|

||||

lrwxrwxrwx. 1 root root 36 Dec 8 2016 cracklib_dict.pwi -> ../../usr/share/cracklib/pw_dict.pwi

|

||||

lrwxrwxrwx. 1 root root 27 Jun 9 2016 libaccountsservice.so.0 -> libaccountsservice.so.0.0.0

|

||||

-rwxr-xr-x. 1 root root 288456 Jun 9 2016 libaccountsservice.so.0.0.0

|

||||

lrwxrwxrwx 1 root root 15 May 17 11:47 libacl.so.1 -> libacl.so.1.1.0

|

||||

-rwxr-xr-x 1 root root 36472 May 17 11:47 libacl.so.1.1.0

|

||||

lrwxrwxrwx. 1 root root 15 Feb 4 2016 libaio.so.1 -> libaio.so.1.0.1

|

||||

-rwxr-xr-x. 1 root root 6224 Feb 4 2016 libaio.so.1.0.0

|

||||

-rwxr-xr-x. 1 root root 6224 Feb 4 2016 libaio.so.1.0.1

|

||||

lrwxrwxrwx. 1 root root 30 Jan 16 16:39 libakonadi-calendar.so.4 -> libakonadi-calendar.so.4.14.26

|

||||

-rwxr-xr-x. 1 root root 816160 Jan 16 16:39 libakonadi-calendar.so.4.14.26

|

||||

lrwxrwxrwx. 1 root root 29 Jan 16 16:39 libakonadi-contact.so.4 -> libakonadi-contact.so.4.14.26

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

**/lib64** 目录下的一些链接

|

||||

|

||||

T在上面展示的 **/lib64** 目录清单列表中,文件模式第一个字母 I 表示这是一个符号链接或软链接。

|

||||

|

||||

### 硬链接

|

||||

|

||||

在 [An introduction to Linux's EXT4 filesystem][15]一文中,我曾探讨过这样一个事实,每个文件都有一个包含该文件信息的节点,包含了该文件的位置信息。上述文章中的[图2][16]展示了一个指向文件节点的单一目录项。每个文件都至少有一个目录项指向描述该文件信息的文件节点,目录项是一个硬链接,因此每个文件至少都有一个硬链接。

|

||||

|

||||

如下图1所示,多个目录项指向了同一文件节点。这些目录项都是硬链接。我曾使用波浪线 (**~**) 表示三级目录项的缩写,这是用户目录的惯例表示,因此在该例中波浪线等同于 **/home/user** 。值得注意的是,四级目录项是一个完全不同的目录,**/home/shared** 可能是该计算机上用户的共享文件目录。

|

||||

|

||||

|

||||

Figure 1

|

||||

|

||||

单一文件系统中的文件硬链接数是有限制的。”文件系统“ 是就挂载在特定挂载点上的分区或逻辑卷而言的,此例中是 /home。这是因为文件系统中的节点号都是唯一的。在不同的文件系统中,如 **/var** 或 **/opt**,会有和 **/home** 中相同的节点号。

|

||||

|

||||

因为所有的硬链接都指向了包含文件元信息的节点,这些特性都是文件的一部分,像所属关系,权限,节点硬链接数目,这些特性不能区分不同的硬链接。这是一个文件所具有的一组属性。唯一能区分这些文件的是包含在节点信息中的文件名。对单靠 **file/inode** 来定位文件的同一目录中的硬链接必须拥有不同的文件名,基于上述事实,同一目录下不能存在重复的文件名。

|

||||

|

||||

文件的硬链接数目可通过 **ls -l** 来查看,如果你想查看实际节点号,可使用 **ls -li** 命令。

|

||||

|

||||

### 符号(软)链接

|

||||

|

||||

软链接(符号链接)和硬链接的区别在于,硬链接直接指向文件中的节点而软链接直接指向一个目录项,即一个硬链接。因为软链接指向一个文件的硬链接而非该文件的节点信息,所以它们并不依赖于文件节点,这使得它们能在不同的文件系统中起作用,跨越不同的分区和逻辑卷。

|

||||

|

||||

软链接的缺点是,一旦它所指向的硬链接被删除或重命名后,该软链接就失效了。软链接虽然还在,但所指向的硬链接已不存在。所幸的是,**ls** 命令能以红底白字的方式在其列表中高亮显示失效的软链接。

|

||||

|

||||

### 实验项目: 链接实验

|

||||

|

||||

我认为最容易理解链接用法及其差异的方法即使动手搭建一个项目。这个项目应以非超级用户的身份在一个空目录下进行。我创建了 **~/tmp** 目录做这个实验,你也可以这么做。这么做可为项目创建一个安全的环境且提供一个新的空目录让程序运作,如此以来这儿仅存放和程序有关的文件。

|

||||

|

||||

### **初始工作**

|

||||

|

||||

首先,在你要进行实验的目录下为该项目中的任务创建一个临时目录,确保当前工作目录(PWD)是你的主目录,然后键入下列命令。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

mkdir temp

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

使用这个命名将当前工作目录切换到 *~/temp**

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

cd temp

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

实验开始,我们创建一个能够链接的文件,下列命令可完成该工作并向其填充内容。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

du -h > main.file.txt

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

使用 *ls -l** 长列表命名确认文件被正确地创建。运行结果应类似于我的。注意文件大小只有 7 字节,但你的可能会有 1~2 字节的变动。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ls -l

|

||||

total 4

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 1 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 main.file.txt

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

在列表中,文件模式串后的数字 1 代表存在于该文件上的硬链接数。现在应该是 1 ,因为我们还没有为这个测试文件建立任何硬链接。

|

||||

|

||||

### **对硬链接进行实验**

|

||||

|

||||

硬链接创建一个指向同一文件节点的目录项,当为文件添加一个硬链接时,你会看到链接数目的增加。确保当前工作目录仍为 **~/temp**。创建一个指向 **main.file.txt** 的硬链接,然后查看该目录下文件列表。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ln main.file.txt link1.file.txt

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ls -l

|

||||

total 8

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 2 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 link1.file.txt

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 2 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 main.file.txt

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

目录中两个文件都有两个链接且大小相同,时间戳也一样。这是同一文件节点的两个不同的硬链接,即该文件的目录项。再建立一个该文件的硬链接,并列出目录清单内容,你可以建立 **link1.file.txt** 或 **main.file.txt** 的硬链接。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ln link1.file.txt link2.file.txt ; ls -l

|

||||

total 16

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 3 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 link1.file.txt

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 3 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 link2.file.txt

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 3 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 main.file.txt

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

注意,该目录下的每个硬链接必须使用不同的名称,因为同一目录下的两个文件不能拥有相同的文件名。试着创建一个和现存链接名称相同的硬链接。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ln main.file.txt link2.file.txt

|

||||

ln: failed to create hard link 'link2.file.txt': File exists

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

显然不行,因为 **link2.file.txt** 已经存在。目前为止我们只在同一目录下创建硬链接,接着在临时目录的父目录,你的主目录中创建一个链接。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ln main.file.txt ../main.file.txt ; ls -l ../main*

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 main.file.txt

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

上面的 **ls** 命令显示 **main.file.txt** 文件确实存在于主目录中,且与该文件在 temp 目录中的名称一致。当然它们是没有区别的两个文件,它们是同一文件的两个链接,指向了同一文件的目录项。为了帮助说明下一点,在 temp 目录中添加一个非链接文件。

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ touch unlinked.file ; ls -l

|

||||

total 12

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 link1.file.txt

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 link2.file.txt

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 main.file.txt

|

||||

-rw-rw-r-- 1 dboth dboth 0 Jun 14 08:18 unlinked.file

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

使用 **ls** 命令的 **i** 选项查看文件节点的硬链接号和新创建文件的硬链接号。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ls -li

|

||||

total 12

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 link1.file.txt

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 link2.file.txt

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 7 Jun 13 07:34 main.file.txt

|

||||

657863 -rw-rw-r-- 1 dboth dboth 0 Jun 14 08:18 unlinked.file

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

注意上面文件模式左边的数字 **657024** ,这是三个硬链接文件所指的同一文件的节点号,你也可以使用 **i** 选项查看主目录中所创建的链接节点号,和该值相同。只有一个链接的文件节点号和其他的不同,在你的系统上看到的不同于本文中的。

|

||||

|

||||

接着改变其中一个硬链接文件的大小。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ df -h > link2.file.txt ; ls -li

|

||||

total 12

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 link1.file.txt

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 link2.file.txt

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 main.file.txt

|

||||

657863 -rw-rw-r-- 1 dboth dboth 0 Jun 14 08:18 unlinked.file

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

现在的硬链接文件大小比原来大,因为多个目录项链接着同一文件。

|

||||

|

||||

我知道下个实验在我的电脑上会成功,因为我的 **/tmp** 目录是一个独立的逻辑卷,如果你有单独的逻辑卷或文件系统在不同的分区上(如果未使用逻辑卷),确定你是否能访问那个分区或逻辑卷,如果不能,你可以在电脑上挂载一个 U盘,如果上述选项适合你,你可以进行这个实验。

|

||||

|

||||

试着在 **/tmp** 目录中建立一个 **~/temp** 目录下文件的链接(或你的文件系统所在的位置)

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ln link2.file.txt /tmp/link3.file.txt

|

||||

ln: failed to create hard link '/tmp/link3.file.txt' => 'link2.file.txt':

|

||||

Invalid cross-device link

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

为什么会出现这个错误呢? 原因是每一个单独的挂载文件系统都有一套自己的节点号。简单的通过文件节点号来跨越整个文件系统结构引用一个文件会使系统困惑,因为相同的节点号会存在于每个已挂载的文件系统中。

|

||||

|

||||

有时你可能会想找到一个文件节点的所有硬链接。你可以使用 **ls -li** 命令。然后使用 **find** 命令找到所有硬链接的节点号。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ find . -inum 657024

|

||||

./main.file.txt

|

||||

./link1.file.txt

|

||||

./link2.file.txt

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

注意 **find** 命令不能找到所属该节点的四个硬链接,因为我们在 **~/temp** 目录中查找。 **find** 命令仅在当前工作目录及其子目录中中查找文件。要找到所有的硬链接,我们可以使用下列命令,注定你的主目录作为起始查找条件。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ find ~ -samefile main.file.txt

|

||||

/home/dboth/temp/main.file.txt

|

||||

/home/dboth/temp/link1.file.txt

|

||||

/home/dboth/temp/link2.file.txt

|

||||

/home/dboth/main.file.txt

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

如果你是非超级用户没有权限,可能会看到错误信息。这个命令也使用了 **-samefile** 选项而不是指定文件的节点号。这个效果和使用文件节点号一样且更容易,如果你知道其中一个硬链接名称的话。

|

||||

|

||||

### **对软链接进行实验**

|

||||

|

||||

如你刚才看到的,不能越过文件系统交叉创建硬链接,即在逻辑卷或文件系统中从一个文件系统到另一个文件系统。软链接给出了这个问题的解决方案。虽然他们可以达到相同的目的,但他们是非常不同的,知道这些差异是很重要的。

|

||||

|

||||

让我们在 **~/temp** 目录中创建一个符号链接来开始我们的探索。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ln -s link2.file.txt link3.file.txt ; ls -li

|

||||

total 12

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 link1.file.txt

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 link2.file.txt

|

||||

658270 lrwxrwxrwx 1 dboth dboth 14 Jun 14 15:21 link3.file.txt ->

|

||||

link2.file.txt

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 4 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 main.file.txt

|

||||

657863 -rw-rw-r-- 1 dboth dboth 0 Jun 14 08:18 unlinked.file

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

拥有节点号 **657024** 的那些硬链接没有变化,且硬链接的数目也没有变化。新创建的符号链接有不同的文件节点号 **658270**。 名为**link3.file.txt** 的软链接指向了 **link2.file.txt** 文件。使用 **cat** 命令查看 **link3.file.txt** 文件的内容。符号链接的文件节点信息以字母 "**l**" 开头,意味着这个文件实际是个符号链接。

|

||||

|

||||

上例中软链接文件 **link3.file.txt** 的大小只有 14 字节。这是文本内容 **link3.file.txt -> link2.file.txt** 的大小,实际上是目录项的内容。目录项 **link3.file.txt** 并不指向一个文件节点;它指向了另一个目录项,这在跨越文件系统建立链接时很有帮助。现在试着创建一个软链接,之前在 **/tmp** 目录中尝试过的。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ ln -s /home/dboth/temp/link2.file.txt

|

||||

/tmp/link3.file.txt ; ls -l /tmp/link*

|

||||

lrwxrwxrwx 1 dboth dboth 31 Jun 14 21:53 /tmp/link3.file.txt ->

|

||||

/home/dboth/temp/link2.file.txt

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

### **删除链接**

|

||||

|

||||

当你删除硬链接或硬链接所指的文件时,需要考虑一些问题。

|

||||

|

||||

首先,让我们删除硬链接文件 **main.file.txt**。注意每个硬链接都指向了一个文件节点。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ rm main.file.txt ; ls -li

|

||||

total 8

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 3 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 link1.file.txt

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 3 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 link2.file.txt

|

||||

658270 lrwxrwxrwx 1 dboth dboth 14 Jun 14 15:21 link3.file.txt ->

|

||||

link2.file.txt

|

||||

657863 -rw-rw-r-- 1 dboth dboth 0 Jun 14 08:18 unlinked.file

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

**main.file.txt** 是第一个硬链接文件,当该文件被创建时。现在删除它仍然保留原始文件和硬盘上的数据以及所有剩余的硬链接。要删除原始文件,你必须删除它的所有硬链接。

|

||||

|

||||

现在山村 **link2.file.txt** 硬链接文件。

|

||||

|

||||

```

|

||||

[dboth@david temp]$ rm link2.file.txt ; ls -li

|

||||

total 8

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 3 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 link1.file.txt

|

||||

658270 lrwxrwxrwx 1 dboth dboth 14 Jun 14 15:21 link3.file.txt ->

|

||||

link2.file.txt

|

||||

657024 -rw-rw-r-- 3 dboth dboth 1157 Jun 14 14:14 main.file.txt

|

||||

657863 -rw-rw-r-- 1 dboth dboth 0 Jun 14 08:18 unlinked.file

|

||||

```

|

||||

|

||||

注意软链接的变化。删除软链接所指的硬链接会使该软链接失效。在我的系统中,断开的链接用颜色高亮显示,目标硬链接闪烁。如果需要修改软链接,你需要在同一目录下建立一个和旧链接相同名字的硬链接,只要不是所有硬链接都已删除。 您还可以重新创建链接本身,链接保持相同的名称,但指向剩余的硬链接中的一个。当然如果软链接不再需要,可以使用 **rm** 命令删除它们。

|

||||

|

||||

**unlink** 命令在删除文件和链接时也有用。它非常简单且没有选项,就像 **rm** 命令一样。然而,它更准确地反映了删除的基本过程,因为它删除了目录项与被删除文件的链接。

|

||||

|

||||

### 写在最后

|

||||

|

||||

我曾与这两种类型的链接很长一段时间后,我开始了解他们的能力和特质。为我所教的Linux课程编写了一个实验室项目,以充分理解链接是如何工作的,并且我希望增进你的理解。

|

||||

|

||||

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

作者简介:

|

||||

|

||||

戴维.布斯 - 戴维.布斯是Linux和开源倡导者,居住在Raleigh的北卡罗莱纳。他在IT行业工作了四十年,为IBM工作了20年多的OS 2。在IBM时,他在1981编写了最初的IBM PC的第一个培训课程。他教了RHCE班红帽子和曾在MCI世通公司,思科,和北卡罗莱纳州。他已经用Linux和开源软件工作将近20年了。

|

||||

|

||||

---------------------------------

|

||||

|

||||

via: https://opensource.com/article/17/6/linking-linux-filesystem

|

||||

|

||||

作者:[David Both ][a]

|

||||

译者:[yongshouzhang](https://github.com/yongshouzhang)

|

||||

校对:[yongshouzhang](https://github.com/yongshouzhang)

|

||||

|

||||

本文由 [LCTT](https://github.com/LCTT/TranslateProject) 原创编译,[Linux中国](https://linux.cn/) 荣誉推出

|

||||

|

||||

[a]:https://opensource.com/users/dboth

|

||||

[1]:https://opensource.com/resources/what-is-linux?src=linux_resource_menu

|

||||

[2]:https://opensource.com/resources/what-are-linux-containers?src=linux_resource_menu

|

||||

[3]:https://developers.redhat.com/promotions/linux-cheatsheet/?intcmp=7016000000127cYAAQ

|

||||

[4]:https://developers.redhat.com/cheat-sheet/advanced-linux-commands-cheatsheet?src=linux_resource_menu&intcmp=7016000000127cYAAQ

|

||||

[5]:https://opensource.com/tags/linux?src=linux_resource_menu

|

||||

[6]:https://opensource.com/article/17/6/linking-linux-filesystem?rate=YebHxA-zgNopDQKKOyX3_r25hGvnZms_33sYBUq-SMM

|

||||

[7]:https://opensource.com/user/14106/feed

|

||||

[8]:https://www.flickr.com/photos/digypho/7905320090

|

||||

[9]:https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

|

||||

[10]:https://opensource.com/article/17/5/introduction-ext4-filesystem

|

||||

[11]:https://opensource.com/article/16/11/managing-devices-linux

|

||||

[12]:https://opensource.com/life/16/10/introduction-linux-filesystems

|

||||

[13]:https://opensource.com/business/16/9/linux-users-guide-lvm

|

||||

[14]:https://opensource.com/life/15/9/everything-is-a-file

|

||||

[15]:https://opensource.com/article/17/5/introduction-ext4-filesystem

|

||||

[16]:https://opensource.com/article/17/5/introduction-ext4-filesystem#fig2

|

||||

[17]:https://opensource.com/users/dboth

|

||||

[18]:https://opensource.com/article/17/6/linking-linux-filesystem#comments

|

||||

Loading…

Reference in New Issue

Block a user